H-043-2: “Sojourn Through Hell”—Vietnamization and U.S. Navy Prisoners of War, 1969–70

The Nixon administration’s “Vietnamization” policy gained a full head of steam in late 1969 and throughout 1970, with the intent to turn as much of the fighting as possible over to Republic of Vietnam forces and withdraw as many U.S. forces as quickly as possible. Not surprisingly, the North Vietnamese Communists were all for this course of action. The U.S. naval component of this process was termed “ACTOV” (“accelerated turnover to the Vietnamese”) involving the “incremental” turnover of the river and coastal combat craft and logistics support network (“precipitous” may actually be a more accurate term). Nevertheless, the approximately 560 officers and men of the Naval Advisory Group did extraordinary work in training and integrating Vietnamese navy personnel into operations in ever-increasing numbers such that by late 1970, entire commands had transitioned to South Vietnamese control.

The Nixon administration and senior U.S. military and naval leaders in Vietnam at the time (including the Commander Naval Forces Vietnam, Vice Admiral Elmo Zumwalt) were not naïve about North Vietnamese intentions. In the spring of 1970, in order to knock the Communists off-balance and protect the Vietnamization effort, the South Vietnamese, with significant U.S. support, launched a series of attacks into Cambodia against Communist staging areas, supply dumps, and the logistics support network that had largely operated for years with impunity due to Cambodia’s supposed neutrality. (The Cambodian government, under Prince Sihanouk, made no serious attempt to prevent the North Vietnamese from using Cambodian territory to run supplies to Communist forces in South Vietnam, at least until March 1970, when Sihanouk was essentially overthrown by a military coup led by anti-Communist General Lon Nol.)

From a military perspective, the U.S. and South Vietnamese incursions into Cambodia that occurred between May and July of 1970 were a qualified success, although that was partly due to the fact that the North Vietnamese learned they were coming and adopted a strategy of withdrawing to remain just out of reach. The operations did capture massive amounts of arms and ammunition. From a U.S. domestic political perspective, the Cambodian incursions resulted in major backlash. Although 50 percent of the U.S. population supported Nixon’s strategy, vociferous opponents accused the Nixon administration of lying to the American people by “widening” the war in Vietnam rather than withdrawing. This led to significant protests, including the killing of four Kent State students (two of whom weren’t even protesters) by the Ohio National Guard, which was, in turn, followed by the bombings and burnings of about 30 Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) buildings on campuses across the country.

Despite the domestic upheaval in the United States, the U.S. Navy kept doing what the U.S. government asked it to do as best it could within ever-increasing political constraints. On 9 May 1970, a combined Vietnamese-American naval task force headed up the Mekong River and into Cambodia. The U.S. contingent included a variety of riverine patrol craft, supported by Helicopter Attack Light Squadron THREE (HAL-3) attack helicopters and Light Attack Squadron FOUR (VAL-4) aircraft, in addition to ten strike assault boats of Strike Assault Boat Squadron TWENTY, a new fast-reaction unit established by Zumwalt. U.S. Naval Advisory Group personnel were embarked on each South Vietnamese vessel. Although, for political reasons, U.S. Navy personnel were not allowed to go past the halfway point to the Cambodian capital of Phnom Penh, the Vietnamese Navy boats were all the way to the capital by the end of the first day, and exhibited generally good performance throughout, suggestive of effective U.S. training. The U.S. Navy boats pulled out of Cambodia by late June, but the South Vietnamese continued to exercise effective control of the waterway while evacuating over 80,000 ethic Vietnamese from Cambodia who had been caught in the ground fighting.

In support of the Cambodian incursion, the U.S. Seventh Fleet beefed up the carrier presence in the South China Sea to three carriers at a time. Carriers that operated in the area during the spring and summer of 1970 included Coral Sea (CVA-43), Ranger (CVA-61), Shangri-La (CVS-38), Bon Homme Richard (CVA-31), America (CVA-66), and Oriskany (CVA-34). Task Force 77 carrier aircraft increased the level of effort against North Vietnamese supply lines through Laos, allowing U.S. Air Force aircraft based in Thailand and South Vietnam to focus on Cambodia.

Since the Johnson administration had halted the bombing of North Vietnam in 1968, the primary target set for U.S. carrier aircraft were trucks, vehicles, troops, and chokepoints along the “Ho Chi Minh Trail” through Laos. U.S. operations over Laos (which, like Cambodia, was supposedly neutral, but made no attempt to keep the North Vietnamese from using their territory) included “Commando Bolt” operations, which involved the use of new EA-6B electronic countermeasures carrier jets, sophisticated air and ground sensor systems, and increasing use of precision-guided bombs to enhance the effectiveness of strikes against the North Vietnamese supply lines. U.S. Navy jets also continued to fly reconnaissance missions over southern North Vietnam, and every once in a while a “tit-for-tat” strike would be ordered against a North Vietnamese target whenever the North Vietnamese fired on one of the U.S. reconnaissance jets.

During this period, Communist activity in the coastal regions of South Vietnam was at a low ebb (the Viet Cong had still not recovered from their devastating losses resulting from the premature Tet Offensive in early 1968). As a result, the U.S. Navy gunfire support presence was drawn down, including the departure of the reactivated battleship New Jersey (BB-62). New Jersey had been reactivated during the Korean War, returned to “mothballs,” and reactivated again in 1968 for the Vietnam War. During her deployment to Vietnam between September 1968 and April 1969, she fired 5,688 rounds of 16-inch and 14,891 rounds of 5-inch shells at enemy positions in both North and South Vietnam. Despite the success of her deployment, New Jersey was ordered deactivated upon her return to port by the Secretary of Defense as a cost-saving move.

Secretary of the Navy John H. Chafee (center right) inspects one of over 3,000 captured North Vietnamese bicycles used to transport munitions at headquarters of the 1st Cavalry Division in Vietnam. The bicycles were part of the equipment captured during the June 1970 operations in Cambodia (USN 1144256).

Meanwhile, though, U.S. and allied forces (including Australia) continued to have significant success in ongoing Operation Market Time, interdicting North Vietnamese attempts to get supplies to Viet Cong forces in South Vietnam via the sea. The North Vietnamese had been sending ships far along the outer reaches of the South China Sea and bringing in supplies via the Cambodian port of Sihanoukville, but the incursion into Cambodia finally put a stop to that. The North Vietnamese also attempted 15 supply missions via trawler into South Vietnam between August 1969 and the end of 1970. Only one made it, and one was destroyed by allied forces. The other 13 turned back after they realized they had been detected and were being tracked.

Throughout all of this, American prisoners of war in North Vietnam, mostly downed U.S. Navy and Air Force aviators and a few Marines, had suffered brutal treatment at the hands of their captors going back to 1964. This treatment included frequent interrogations accompanied by torture, as well as brutal beatings and grossly inadequate diet and medical care. One POW would later describe it as a “sojourn through hell.” Only in late 1969 did the barbaric treatment of U.S. POWs ease up somewhat, although it was still a far cry from what the Geneva Conventions called for. This change was due to a number of reasons, but a significant factor were the actions of the senior Navy POW, Captain James Bond Stockdale, and the most junior Navy POW, Seaman Apprentice Douglas B. Hegdahl III.

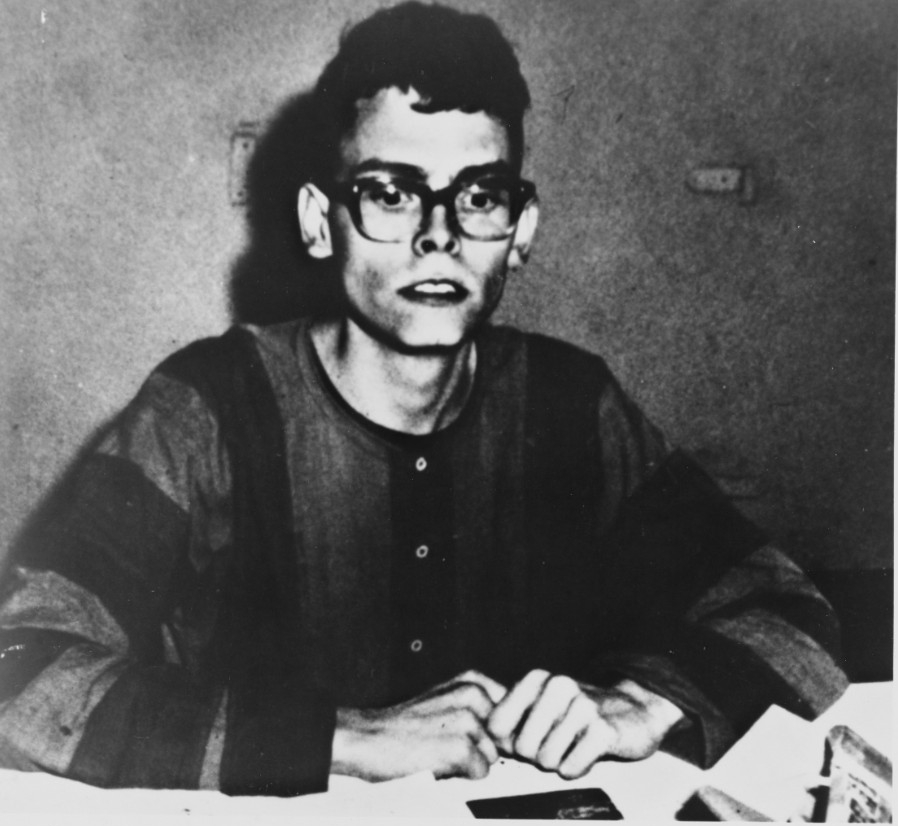

On 5 August 1969, the North Vietnamese made a big mistake when they released Seaman Doug Hegdahl as a propaganda ploy, which backfired. Known as “The Incredibly Stupid One” by his captors, Hegdahl had been blown overboard by a gun blast on his ship, the cruiser Canberra (CAG-2), off the coast of Vietnam on 6 April 1967, subsequently fell into the hands of the North Vietnamese, and wound up in the “Hanoi Hilton.” As the junior-most captive, Hegdahl played dumb to the hilt, even claiming that he could not read or write, and the Vietnamese assigned him to do menial tasks around his camp, which actually gave him much greater access to other prisoners (and opportunities to sabotage five trucks). What the North Vietnamese did not know was that during his year and a half of captivity, Hegdahl memorized the names, capture date, method of capture, and personal information of about 256 other POWs (to the tune of “Old MacDonald Had a Farm”). Hegdahl was ordered by his superior officers to accept the early release (despite the POWs’ prohibition against doing so) in order to bring back this vital information to U.S. military authorities, as well as provide eye-witness confirmation that the North Vietnamese had engaged in torture of prisoners.

Up to this point in the war, the United States did not know specific information about which aviators had been captured, killed while being shot down, died in captivity, or were missing in action and unaccounted for. The fact that the North Vietnamese were torturing prisoners was first confirmed when POW Commander Jeremiah Denton famously blinked his eyes in Morse code to signal “T-O-R-T-U-R-E” when forced to participate in a propaganda broadcast in 1966 (for which he would receive extra torture and a Navy Cross). Hegdahl provided additional confirmation in far greater detail. After his release from captivity, Hegdahl was ordered to Paris to assist the U.S. delegation at the interminable “peace talks” in confronting the North Vietnamese with evidence of their flagrant violation of the Geneva Accords.

Another reason that the North Vietnamese relented somewhat in their abuse of prisoners was due to the ongoing wall of resistance put up by virtually all the U.S. POWs by refusing to participate in North Vietnamese propaganda activities. The Vietnamese began to realize that torture was not having the desired effect. This, and the resistance of the POWs to interrogation and torture, was in significant measure due to the senior U.S. Navy officer in captivity, Captain James B. Stockdale, who had been shot down over North Vietnam and captured in September 1965. Stockdale was specifically instrumental in establishing and enforcing a POW code of conduct tailored for the situation within North Vietnamese prison camps, and it was adherence to this code that enabled many of the POWs to endure the horrific treatment and still survive, and for almost all to return with honor at the end.

Stockdale would be present at both the beginning and the end of significant U.S. Navy involvement in the Vietnam War. He would earn his first Distinguished Flying Cross as skipper of VF-51, embarked on Ticonderoga (CVA-14) during the first (real) Gulf of Tonkin incident on 2 August 1964. He flew one of the four F-8 Crusaders that attacked North Vietnamese P-4 torpedo boats attempting to attack the U.S. destroyer Maddox (DD-731), while Maddox was conducting a “DeSoto” mission (signals intelligence collection) off North Vietnam. On 4 August, he also flew in support of Maddox and destroyer Turner Joy (DD-951) when they were engaged in firing on what (after the war) were determined to be phantom radar targets during the second Gulf of Tonkin incident. In response to the second attack, Stockdale then flew on the retaliatory strike on North Vietnamese targets on 5 August on the order of President Lyndon Johnson. During this mission, Lieutenant (j.g.) Everett Alvarez, Jr.’s A-4 Skyhawk was shot down and he became the first U.S. pilot captured by the North Vietnamese, and the second longest U.S. POW to be held in captivity (over eight years).

Stockdale returned for another Vietnam combat deployment as the Commander Carrier Air Group TWELVE embarked in carrier Oriskany, during which he would earn a second Distinguished Flying Cross before his A-4 Skyhawk was hit and disabled by North Vietnamese ground fire and he was forced to eject. As the senior U.S. naval officer, Stockdale was singled out for exceptionally severe treatment in order to break his will, especially after the North Vietnamese figured out he was the leading figure in the “resistance.” Stockdale was one of a group of 11 POWs (known as the “Alcatraz Gang,” which also included Commander Denton) who the North Vietnamese determined to be particularly incorrigible and uncooperative, subjecting them to long periods of solitary confinement interspersed with brutal torture.

Stockdale would, of course, receive no medals until after his release in 1973, but during the course of his seven and a half years in captivity, he would be awarded two Distinguished Service Medals for his role as senior U.S. Navy officer, along with four Silver Stars and two Bronze Stars with Combat V for his resistance to multiple incidents of severe torture. He would also earn a Legion of Merit with Combat V and the Prisoner of War Medal for his time in captivity.

On 4 March 1976, Stockdale would be presented with the Medal of Honor for his actions on 4 September 1969 as set forth in the citation:

For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty on 4 September 1969 while senior officer in the Prisoner of War camps of North Vietnam. Recognized by his captors as the leader of the Prisoners of War resistance to interrogation and in their refusal to participate in propaganda exploitation, Rear Admiral (then Captain) Stockdale was singled out for interrogation and attendant torture after he was detected in a covert communications attempt. Sensing the start of another purge, and aware that his earlier attempts as self-disfiguration to dissuade his captors from using him for propaganda purposes had resulted in cruel and agonizing punishment, Rear Admiral Stockdale resolved to make himself a symbol of resistance regardless of personal sacrifice. He deliberately inflicted a near mortal wound to his person in order to convince his captors of his willingness to give up his life rather than capitulate. He was subsequently discovered and revived by the North Vietnamese who, convinced of his indomitable spirit, abated in their employment of excessive harassment and torture toward all of the Prisoners of War. By his heroic action, at great peril to himself, he earned the everlasting gratitude of his fellow prisoners and of his country. Rear Admiral Stockdale’s valiant leadership and extraordinary courage in a hostile environment sustained and enhanced the finest traditions of the United States Naval Service.

By the end of 1970, most U.S. Navy activity in Vietnam had greatly wound down (until the North Vietnamese “Easter Offensive” in 1972). Although the worst of the torture abated, for the U.S. POWs in North Vietnam the psychological torment continued with no end in sight, as the enemy appeared determined to use the POWs as bargaining chips in negotiations until the bitter end. However, thanks to the guile of Doug Hegdahl and the extreme heroism of Stockdale and other U.S. POWs in refusing to give in to North Vietnamese torture, the treatment of the POWs between late 1969 and their release in 1973 was slightly less uncivilized.

Sources include: The Battle Behind Bars: Navy and Marine POWs in the Vietnam War, by Stuart I Rochester (Washington, DC: NHHC/Naval Historical Foundation, 2010), and By Sea, Air and Land: An Illustrated History of the U.S. Navy and the War in Southeast Asia, by Edward J. Marolda (Washington, DC: Naval Historical Center, 1994).

Seaman Douglas B. Hegdahl appears gaunt and emaciated before his release from North Vietnam after two and a half years of captivity. His weight loss was about 60 pounds. The young sailor accidentally fell overboard while his ship was in the Gulf of Tonkin in April 1967. He was picked up by North Vietnamese fishermen, who turned him over to the military. Hegdahl and two other Americans were freed by the North Vietnamese on 5 August 1969 (70-2654).