H-Gram 044: "Floating Chrysanthemums"—The Naval Battle of Okinawa

3 April 2020

Contents

75th Anniversary of World War II

Operation Iceberg: Background to the Invasion of Okinawa

The Battle of Okinawa was the bloodiest battle of the Pacific War and lasted almost three months, from late March to June 1945. Over 4,900 U.S. Sailors died, more than U.S. Army (4,675) and U.S. Marine Corps (2,938) personnel did in the land battle. Almost the entire Japanese garrison of 77,000 died, along with about half the civilian population of Okinawa. The island was the key strategic stepping-stone necessary for follow-on operations to invade Japan. To accomplish the mission, the U.S. Navy had to transport, supply, and defend over 500,000 U.S. Army and Marines over vulnerable logistics lines thousands of miles long, and then defend the forces on the island while in range of thousands of Japanese land-based aircraft, whose kamikaze suicide tactics made them much more effective than conventional attackers.

The Japanese strategy ashore, in the air, and on the sea, was to drag out the fight as long as possible, while inflicting as many casualties as possible, and make it clear to the Allies that any invasion of Japan would be enormously costly as the Japanese proved their willingness to fight and die to the last man. In the case of the kamikaze, this meant choosing to sacrifice their lives for the cause. Although the idea of the kamikaze, to knowingly intend to die, was alien to an American mindset, there were innumerable examples of U.S. sailors demonstrating resolve as great as the Japanese pilots. Gunners stood their ground, firing on kamikaze to the bitter end (20-mm gunners “died in the straps”), other times continuing to fire as their ship burned around them. Damage control teams repeatedly refused to give up on their ships even when it seemed all hope was lost; sometimes they pulled off a miracle, sometimes they didn’t, but they often died trying. The fuel in the kamikaze aircraft resulted in more fire on impact than conventional bombs and, as a result, among the many Sailors wounded was a high proportion of severe burn injuries.

The Japanese may have lost the battle and lost the island, but they also made their point. By the time the battle was over, there was no doubt in anyone’s mind just how horrific the casualties would be on both sides in any invasion of Japan.

For more on the background for the invasion of Okinawa, please see attachment H-044-1.

“Floating Chrysanthemums”: The Naval Battle of Okinawa, Part 1

To paraphrase Winston Churchill, if the U.S. Navy should last for 1,000 years, the Battle of Okinawa should be remembered as its “finest hour.” For almost three months, the ships of the U.S. Navy operated at the end of an immensely long logistics trail, constantly within range of large numbers of land-based aircraft, defending the U.S. Army and Marine forces locked in a protracted bloody battle ashore on Okinawa. Facing an onslaught of over 1,400 kamikaze attacks by pilots determined to die to defend their homeland, the ships of the U.S. Navy didn’t flinch, despite horrific casualties. Some of the ships that took the worst of the kamikaze attacks survived and some didn’t; there was a significant degree of chance involved in determining the outcome. What was consistent throughout, however, was the extraordinary valor of the ships’ crews. At Okinawa, the price of victory was extremely high: over 4,900 U.S. Sailors gave their lives for our nation and that sacrifice deserves to be remembered forever.

The initial two weeks of the invasion of Okinawa went reasonably well, and losses were relatively light, with the exception of destroyer Halligan (DD-584), which hit a mine on 26 March and sank with heavy loss of life (153) when her magazine blew. The minesweeper Skylark (AM-63) hit a mine and sank. The gunboat LCI(G)-82 was sunk by a small Japanese suicide boat. Frequent raids by small groups of kamikaze aircraft and conventional air strikes took a toll, with two fleet carriers (Franklin—CV-13—and Wasp—CV-18), escort carrier Wake Island (CVE-65), five destroyers, one destroyer escort, one destroyer-minesweeper, one destroyer transport, and six attack transport/cargo ships being damaged enough to be put out of action for more than 30 days.

The first of ten major kamikaze attacks occurred on 6 and 7 April 1945. The Japanese term was Kikusui (“Floating Chrysanthemums”) Operation No. 1, in which 355 kamikaze aircraft and another 340 planes in a conventional strike and escort roles attacked U.S. forces off Okinawa. U.S. naval intelligence knew the major raid was coming and senior U.S. commanders were warned, and the ships received general warning. Many of the kamikaze pilots had much less experience then those at Lingayen Gulf in January 1945, and many fell easy prey to the large numbers of radar-directed U.S. Navy fighters. Those that made it through the fighter gauntlet tended to go after the first ship they saw, and the U.S. destroyers on the northern radar picket stations bore the brunt of the attacks.

The destroyers Bush (DD-529) and Colhoun (DD-801) were sunk after epic fights against overwhelming odds and despite extraordinary damage control efforts. The destroyer-minesweeper Emmons (DMS-22) also put up a fight for the ages before she succumbed. Epic damage control efforts saved destroyers Newcomb (DD-586), Leutze (DD-481), Witter (DE-636), and Morris (DD-417) from sinking, although their damage was so severe that they would not be repaired. Of this group, Newcomb and Luetze’s heroic fight was one worthy of legend. Four more destroyers and two destroyer escorts were badly damaged and put out of action for at least 30 days. The kamikaze also sank an LST and two Victory ships loaded with ammunition. The fleet carrier Hancock (CV-19) was hit on the second day of Kikusui No. 1 and damaged enough that she had to return to the States.

As bad as it was, from the Japanese perspective, the results of Kikusui No.1 were far less than they hoped, given the numbers of aircraft that they sacrificed. That wouldn’t stop them from trying nine more times in the next two months with mass wave attacks (and small-scale attacks continued almost constantly). Kikusui No. 1 was the largest such mass attack, but it wouldn’t be the most damaging.

For more on the first weeks of the Naval Battle of Okinawa and Kikusui No. 1 up to the start of Kikusui No.2 on 11 April 1945, please see attachment H-044-2. H-Gram 045 will continue the story.

“Operation Heaven Number One” (Ten-ichi-go): The Death of Yamato, 7 April 1945

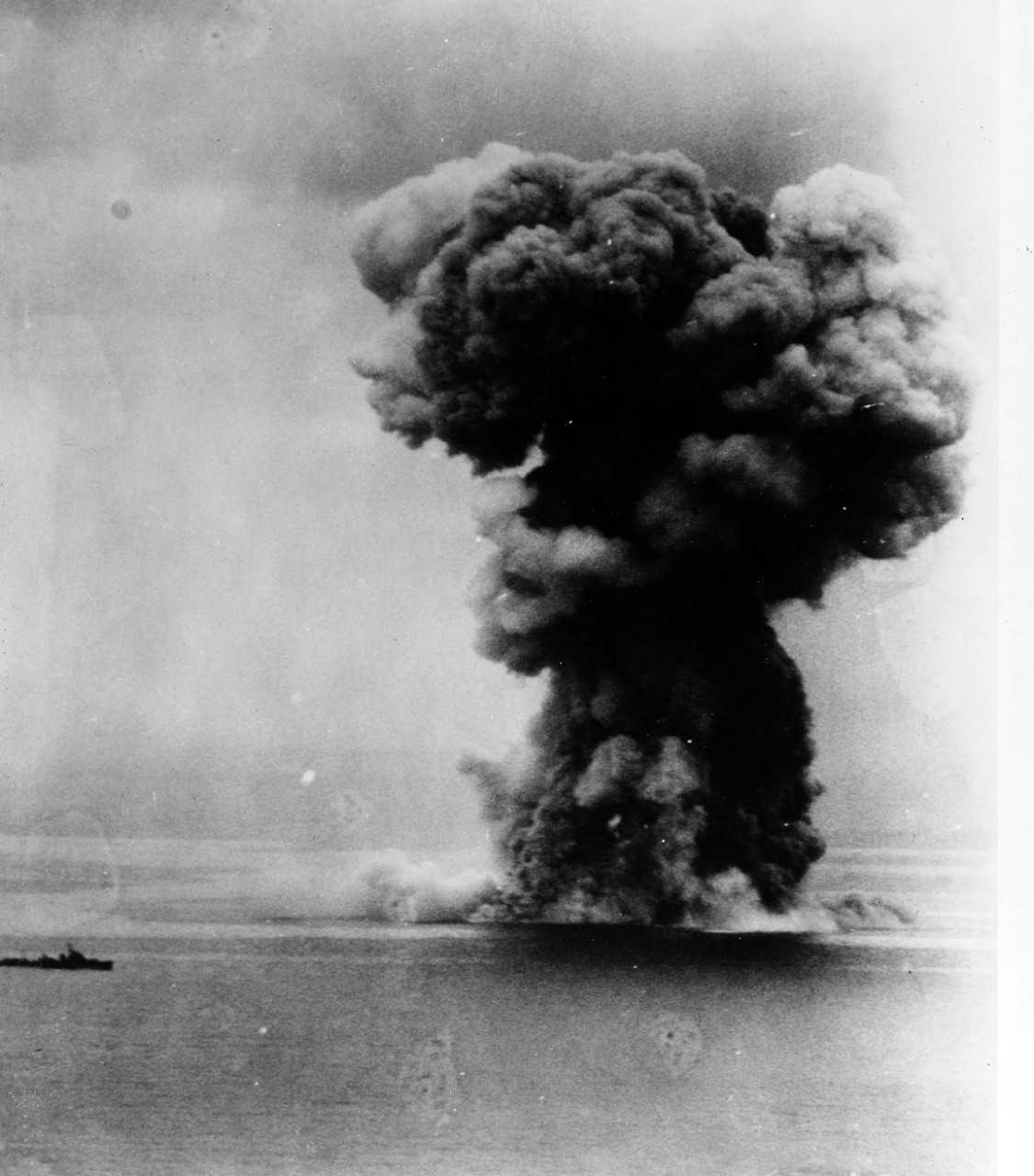

The Japanese super-battleship Yamato, the most powerful battleship in the world with her 18-inch guns, sortied from Japan on 6 April 1945 to oppose the U.S. landings on Okinawa. She would be no match for 390 carrier aircraft from the U.S. Fast Carrier Task Force (TF 58) that swarmed Yamato on 7 April 1945 and ensured she didn’t get anywhere near Okinawa. U.S. naval intelligence knew the details of the operation almost before senior Japanese navy commanders (and before the skippers of Yamato, the light cruiser Yahagi, and the eight destroyers that would escort Yamato on a one-way suicide mission as the "Surface Special Attack Force"—without air cover). Those same skippers argued vociferously against the mission, believing it would be futile and wasteful, or as Captain Tameichi Hara of Yahagi stated, “like throwing an egg against a rock.” However, in the end, every one of those skippers executed their orders to the best of their ability.

With the advance warning, U.S. commanders Admiral Raymond Spruance (Fifth Fleet), Vice Admiral Marc Mitscher (CTF 58), and others were ready. U.S. submarines picked up Yamato as she exited the Inland Sea and tracked her all night. U.S. scout planes from the TF 58 carriers, and Mariner flying boats operating from a tender at Kerama Retto (southwest of Okinawa), knew where to find her and tracked her all morning. At 1000 on 7 April, five fleet carriers and four light carriers of TF 58 launched a first wave of 280 fighters, dive-bombers, and torpedo bombers. Not long afterward, three fleet carriers and one light carrier launched 110 more aircraft. Although 53 aircraft from the first wave didn’t find Yamato in the difficult cloud conditions, it didn’t matter. The Japanese force put up a valiant fight, and Japanese skippers demonstrated their extraordinary skill at avoiding bombs and torpedoes through maneuver; but the great volume of anti-aircraft fire was also wildly inaccurate. Cumulative damage took its toll on Yamato and, by the end, both she and Yahagi had become torpedo and bomb sumps.

For the loss of ten aircraft and 12 men, the aviators of TF 58 sank Yamato, Yahagi, and four destroyers (two sunk, two scuttled), and one of the surviving destroyers had to steam backwards to Japan without her bow. About 4,240 Japanese sailors (3,055 from Yamato alone) gave their lives for the emperor and to defend their homeland. They knew their mission was doomed from the start, but they did their duty anyway. But, like their kamikaze brothers, they made a statement that they would never quit, no matter the odds, and they were prepared to fight to the death. The United States certainly got the message that an invasion of Japan would be a bloodbath of extreme proportions for both sides.

For more on the sinking of Yamato, please see attachment H-044-3.

As always, you are welcome to disseminate H-grams further as you desire. “Back issues” can be found at Naval History and Heritage Command’s website. NHHC’s homepage has much more information about the Battle for Okinawa and many other events in U.S. naval history.