H-033-5: The North Sea Mine Barrage and the Sinking of the USS Richard Bulkeley

The USS Richard Bulkeley was a wooden minesweeping trawler, leased from the Royal Navy on 31 May 1919, acquired for the purpose of sweeping mines that had been laid by the U.S. Navy and the Royal Navy across the northern end of the North Sea during the war in 1918. It served as the flagship of a division of four minesweepers operating from Kirkwall, Scotland. Commander Frank King assumed command of Richard Bulkeley on 7 July 1919. King was a 1907 graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy, and had served on battleships and armored cruisers before attaining the rank of commander just before the war ended on 21 September 1918.

By July 1919, the vast majority of U.S. Sailors and Soldiers who had deployed to the European theater during World War I had returned stateside. However, U.S. and British minesweepers continued to work to clear the over 70,000 mines that had been laid across the northern end of the North Sea in 1918 in an attempt to bottle up German U-boats.

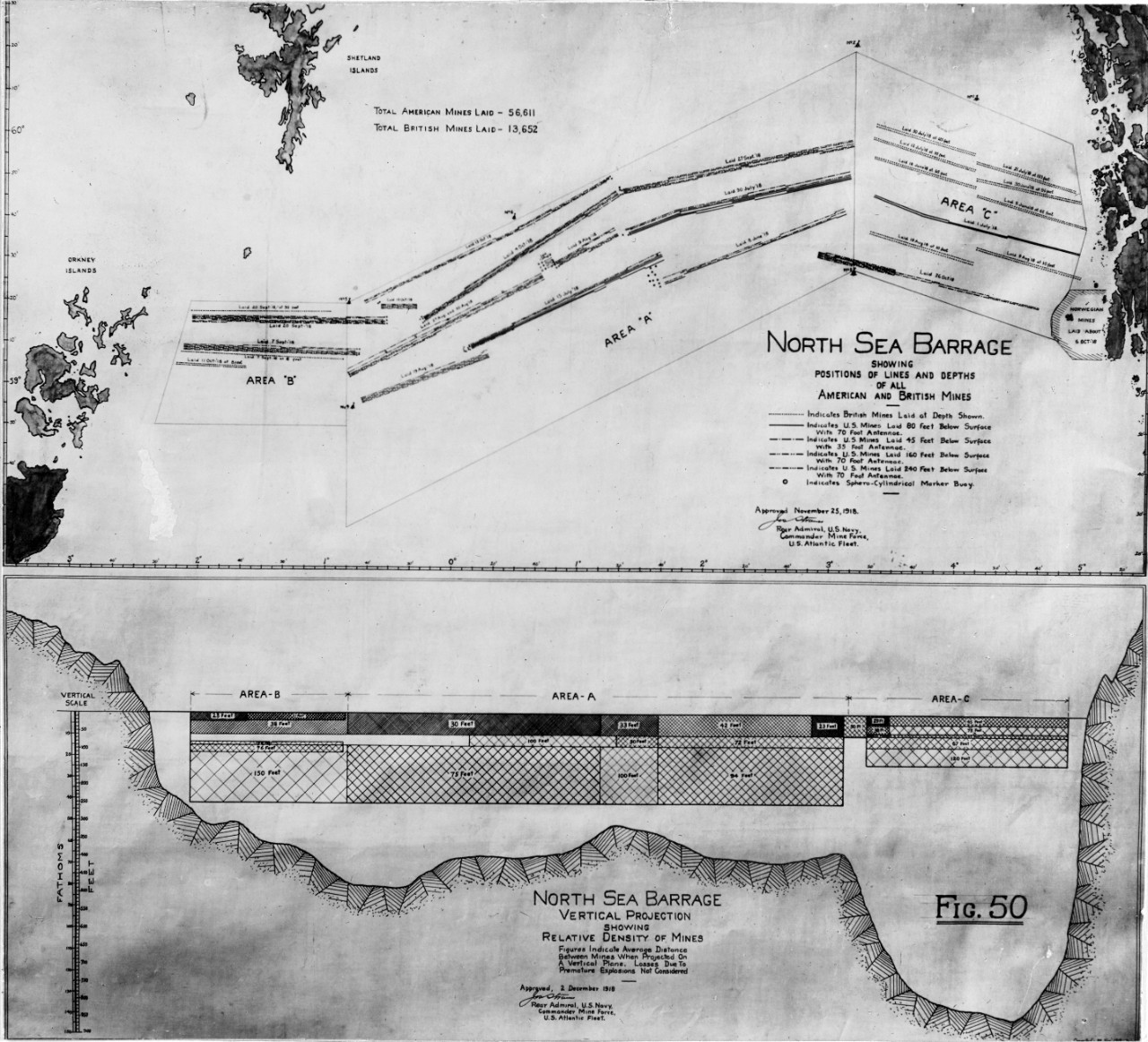

The North Sea mine barrage was a massive minefield laid across the 200–nautical mile gap between the Orkney Islands, just north of Scotland, and Norway. The field was first proposed by a British admiral in 1916 in order to impede U-boat access to the Atlantic via the North Sea. However, it met with little enthusiasm, partly due to the challenging depth of water (900 feet, when minefields to that point had only been laid in water up to about 300 feet). Worse, it was calculated that it would take 400,000 mines to create an effective barrier, which would require an extraordinary (and actually insurmountable) expenditure of resources. Additionally, there would be risk to British (and neutral) ships as well. When the United States entered the war, the senior U.S. naval officer in the European theater, Vice Admiral William S. Sims, did not support the idea, believing it would be an ineffective squandering of resources and, when U.S. Navy leaders in Washington proposed it, the British rejected the idea.

It was the U.S. development of the Mark 6 “antennae mine,” led by Rear Admiral Ralph Earle, the genius who was the chief of the Bureau of Ordnance before and during World War I, responsible for many innovations, including the naval railway gun (see H-Gram 021), that made the mine barrage feasible. The Mark 6 was similar to a standard moored contact mine in that when laid, an anchor would moor it to the bottom, the mine itself would float at a pre-determined depth below the surface, and would be activated when a ship hit one of its “horns,” which would cause a chemical reaction and an electric charge that would detonate the mine. The innovation was that the Mark 6 also deployed copper wire antennae attached to a float that would extend above the mine within the lethal radius of the mine explosive. If a submarine hull touched the antennae, it would detonate the mine and sink the submarine. As a result, it took far fewer mines to make an effective barrier, so only 100,000 would be needed to cover the entrance to the North Sea. This, however, was still an immense expenditure of resources, but, as the tide of the U-boat war had not yet turned, the Allies were increasingly desperate to do anything to stop the U-boats. The Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Franklin Roosevelt, convinced President Woodrow Wilson to overrule Sims’s objections and approve the North Sea barrage.

n October 1917, the U.S. Navy ordered 80,000 Mark 6 mines. Two older “protected cruisers,” already converted to minelayers before the war, and eight civilian steamships converted to minelayers during the war deployed to Scotland, and another 24 steamships were configured as mine-carrying freighters to transport the mine components across the Atlantic, where they were assembled in Scotland. One of the converted minelayers was Shawmut, which would be sunk at Pearl Harbor under a different name: Oglala (CM-4). The hasty transport and assembly of the mines and explosives was a disaster waiting to happen that fortunately did not.

The British laid mines off the Orkneys and just outside neutral Norwegian territorial waters, while the U.S. force laid mines across the central part of the gap. The U.S. North Sea Mine Force was commanded by Rear Admiral Joseph Strauss, embarked on his flagship, the destroyer tender USS Black Hawk (AD-9). Commencing in June 1918 until the war ended, the U.S. force would lay 56,571 of the total 70,177 mines in the barrage, which still had some gaps when the war ended. About 3 to 5 percent of the mines prematurely detonated as soon as they went into water, and on some operations as many as 14 to 19 percent prematurely detonated, which caused great anxiety among the crews of the minelayers. The minelaying operations were escorted by Royal Navy destroyers, and covered by a force of battleships (including on several occasions U.S. battleships) to prevent the German navy from interfering.

The effectiveness of the mine barrage was hotly debated, particularly given the immense cost. The barrage is believed to have had a significant adverse morale effect on the German submarine force, although even that is debated. Four U-boats are believed to have been destroyed by the barrage (including U-156, which laid the mines that sank the armored cruiser San Diego–ACR-6–off Fire Island in July 1918, the largest U.S. Navy warship lost in the war). Two other U-boats are presumed to have been lost in the barrage, and another two were possibly lost. Five U-boats disappeared for unknown reason and might also have been lost due to the barrage. These figures are out of a total of 217 U-boats lost to all causes during World War I. Eight U-boats were damaged by the mines.

The operation to sweep the mines was even more challenging than laying the mines because a process to sweep the antennae “influence” mines had not been invented. It took most of the winter of 1918–19 to develop an electrical protective device for the steel-hulled minesweepers. The concept was devised by Ensign Dudley A. Nichols. Although his idea didn’t pan out, the study of it resulted in one that did, which was developed further by Navy engineers.

The general principal for sweeping the mines was to tow a serrated wire between two ships on parallel course, with the wire held down at depth by “kites.” The wire would cut the mine cable, causing the mine to float to the surface to be destroyed by gunfire. The wooden-hulled trawlers would sweep the mines closest to the surface, while the steel-hulled sweeps would follow behind for the deeper mines (so there would be no chance of the steel hull hitting the antennae wire).

The U.S. sweep operation was also commanded by Rear Admiral Strauss and initially consisted of 12 steel-hulled Lapwing-class minesweepers (named after birds) and 18 wooden-hulled sub chasers. This was quickly deemed inadequate and the vessels were augmented by 16 more Lapwings, and 20 trawlers, leased from the British, with American crews (including Richard Bulkeley). Tangled and lost sweeping gear were common problems, which caused mines to detonate prematurely. Ultimately, one third of the ships involved would be damaged by exploding mines and several men were killed in sweeping accidents.

On 7 July 1919, the U.S. flotilla of 43 minesweepers and supporting vessels departed Kirkwall, Scotland, to commence the fourth of seven minesweeping operations that would take place between April and September of 1919. The flotilla included Lapwing minesweepers, and submarine chasers and wooden-hulled minesweepers, which included Richard Bulkeley. Between 7 and 17 July, nine of these vessels would be damaged by exploding mines and the Richard Bulkeley would be sunk.

The Lapwing-class minesweeper Pelican (AM-27) would also have been sunk had it not been for the daring efforts of other minesweepers in the group, which rallied around her even after she had caused the detonation of six mines in her vicinity in quick succession, bursting seams and causing her to begin to sink. Auk (AM-38) and Eider (AM-17) tied up along each side of Pelican to keep her afloat, and Teal (AM-23) took all three ships in tow.

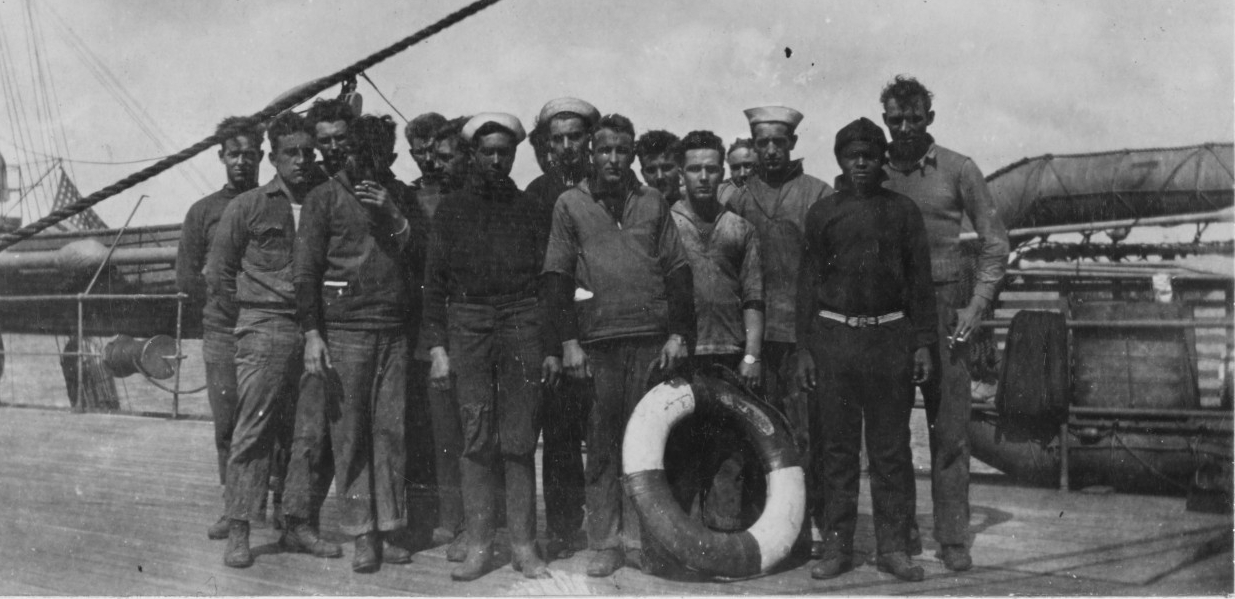

Richard Bulkeley was the flagship for one of the five divisions of trawlers and was sweeping in concert with another trawler, probably George Clark. Just prior to sunset on 12 July, a mine fouled in the kite of her sweep gear was hauled up as the gear was being retrieved at the end of the day. Despite an attempt to pay out the line quickly, the mine exploded close aboard. The ship sank before any ships could reach her, but George Clark was able to rescue 12 survivors from the water.

The flagship of Trawler Division 4, William Johnson, also joined the search. The division commander, Commander Ellis Lando, USN, jumped in the cold water to rescue unconscious Ship’s Cook First Class Antino Perfido, who, however, succumbed to his injuries and hypothermia. Lando was awarded a Distinguished Service Medal for his heroic act. All told, seven of Richard Bulkeley’s crew were lost, including Commander Frank King and six Sailors. Of note, as the war was over, King is not listed on the “killed in action” panel in Memorial Hall at the U.S. Naval Academy. One of the Sailors, Seaman Second Class John V. Mallon, remained at his post on the bridge as a signalman and went down with the ship. He was also awarded a Navy Distinguished Service Medal, although details of the citation are unknown.

The citation for Commander Kings’s Navy Distinguished Service Medal follows:

“For exceptional meritorious service in a duty of great responsibility as commander of a division of trawlers, engaged in the difficult and hazardous operation of sweeping for and removing mines in the North Sea Barrage; and especially for his heroic actions on the destruction by mine explosion of his flagship, the RICHARD BULKELEY, of which he was the commanding officer. Although stunned by the explosion, he made every effort to save the lives of and to rescue men trapped by steam in the fire-room. The rapid sinking of the vessel prevented his success in the undertaking. Finding the ship about to sink, he proceeded to the bridge, where he took his station, and went down with the ship.”

The destroyer USS King (DD-242) was named in his honor and participated in the North Atlantic neutrality patrol (undeclared war with Nazi Germany) and performed ASW patrol duties during the war on the U.S. West Coast and in the Aleutian Islands, participating in the bombardment of Kiska in August 1942.

Following the loss of Richard Bulkely, Rear Admiral Strauss decided that the hulls of the wooden trawlers were too weak to withstand close mine explosions. Excepting six retained for supply purposes, he returned them to the British. On 30 September 1919, Strauss declared the sweeping operation complete, although exactly how many of the mines were actually swept is unknown, since many had already sunk or broken free. Probably only about 40 percent of the mines were actually swept. Mines continued to be a danger in the North Sea for many years, and several merchant ships lost in the 1920s were probably sunk by leftover mines.

Sources include: “Attacking the U-Boat: The North Sea Mine Barrage” by NHHC historian Dr. Dennis Conrad, 2018; “The Northern Barrage: Taking Up the Mines” by NHHC historian Chris Martin, 2017; America’s Sailors in the Great War: Seas, Skies and Submarines by Lisle A. Rose, University of Missouri Press, 2017; “A Dark Day” at davidbruhn.com.