H-041-6: Trieste and the First Dive to Deepest Part of the Oceans, January 1960

The deep-diving bathyscaphe Trieste, launched in 1953, was designed by Swiss scientist August Piccard, built in Italy, and initially operated by the French navy. Trieste was purchased by the U.S. Navy in 1958 for $250,000 (roughly $2.2 million to today) for the purpose of conducting deep-dive research. Trieste was assigned to the Naval Electronics Laboratory in San Diego and conducted some deep dives off the West Coast before being shipped to Guam.

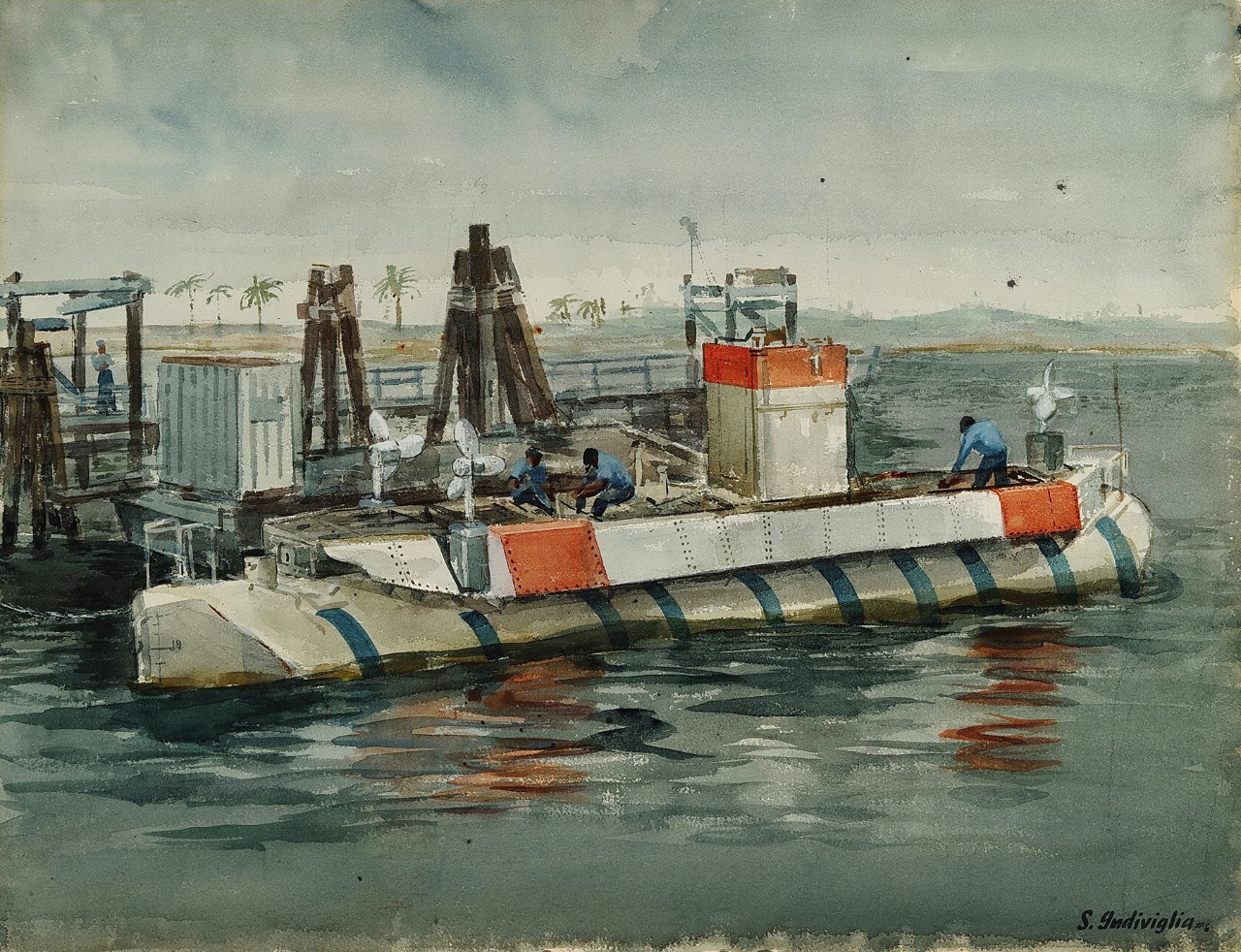

Trieste was about 50 feet long. Most of its hull held 22,000 gallons of aviation gasoline for buoyancy, plus water ballast tanks and releasable iron ballast (held by electromagnets so that if there was an electrical failure, the iron ballast would automatically drop and the bathyscaphe would rise). The crew of two rode in a sphere slung underneath. The original Trieste sphere was designed to reach a 20,000-foot depth, but, after purchase, it was replaced with a German Krupp-manufactured sphere rated for 36,000 feet (and was actually over-designed, with walls 5 inches thick).

Unlike the U.S. rocket and space program, the U.S. deep-sea diving program was deliberately conducted with no publicity. Chief of Naval Operations Arleigh Burk knew about it, but few others not directly associated with it did. (The Navy had suffered several embarrassing missile launch failures, after much publicity beforehand, and Burke was in no mood for a repeat.) Trieste was shipped to Guam, where it conducted seven test dives in preparation for an attempt to reach the bottom of Challenger Deep, the deepest part of the ocean in the world, located about 260 nautical miles southwest of Guam. The operation was designated Project Nekton.

On 23 January 1960, the auxiliary ocean tug USS Wandank (ATA-204) arrived at the dive location with Trieste in tow. Wandank served as the support and communications relay ship for the operations while USS Lewis (DE-535) provided additional support. The weather was not especially favorable, and Trieste had suffered damage during the transit. The crew of Trieste for the deep dive was the officer-in-charge, Lieutenant Don Walsh, and the pilot, Swiss engineer Jacques Piccard, son of Trieste’s designer. After consultation, Walsh and Piccard deemed that the damage was not mission critical and decided that, despite the rough seas, they would conduct the dive anyway. As Trieste was preparing to dive, a message came in from San Diego directing that the dive be cancelled. In the tradition of “Nelson’s blind eye,” the project director, Dr. Andreas Rechnitzer, pocketed the message, had a leisurely breakfast, and then reported back that Trieste was passing 10,000 feet—too late.

The dive commenced a couple of hours after sunrise and went according to plan, although there were more thermocline layers than expected. At each layer, Trieste had the option to let the AVGAS cool in order to penetrate the layer, which would take additional time, or to release some of the reserve AVGAS. Since it was critical for Trieste to return to the surface before dark, Walsh and Piccard opted to expend some of their reserve. At a depth of 32,400 feet, there was a shudder and a noise, from an undetermined cause. In deciding whether to continue the dive, Walsh later said if it had been serious, they both already would have been “red mush.”

The descent took four hours and 47 minutes and reached the bottom at 35,797 feet (the depth gauge read 37,800 feet, but turned out to have been incorrectly calibrated). The plan called for Trieste to remain on the bottom for 30 minutes, but after 20 minutes, the cloud of sediment raised by the submersible precluded any further observation. Walsh was somewhat surprised to discover that they could still communicate with Wandank while they were on the bottom— which had not been expected. Walsh and Piccard observed sparse marine life on the bottom, but their report of a type of “flatfish” provoked scientific controversy and is generally considered to be erroneous, as fish aren’t believed to be able to live below 27,000 feet of depth.

After dropping the iron ballast, the ascent took three hours and 15 minutes. Upon reaching the surface, Walsh and Piccard discovered that the noise they had heard was that the viewing port in the entrance/exit tube had cracked—due to temperature change rather than pressure—as the entrance tube was free-flooded during operations. Nevertheless, care had to be taken while blowing compressed air to de-water the tube, because had the view port shattered and the tube remained flooded, they would have been trapped inside the sphere for however long it took to tow Trieste back to port. Although there was intent to conduct further dives, it turned out that Trieste could not be reloaded with iron ballast while at sea. It would be over 50 years before another attempt would be made to reach Challenger Deep.

Lieutenant Don Walsh was a 1954 graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy. After a couple years aboard the attack cargo ship USS Mathews (AKA-96), he was selected for submarine duty and served aboard USS Rasher (SS-269), one of the most successful submarines of World War II. While aboard Rasher, Walsh was informed not to bother applying for the Naval Nuclear Power Program due to his relatively low class standing at the Naval Academy. According to Walsh, the detailer informed him, “you are officially stupid.” Despite this discouragement, while assigned to the staff of Submarine Flotilla 1, he volunteered for the fledgling deep-dive program (and would become Navy Submersible Pilot No. 1). Walsh would get the last laugh, since he became the only lieutenant in the U.S. Navy to be wearing a Legion of Merit, personally presented by President Dwight D. Eisenhower. Walsh went on to be one of the first U.S. naval officers to earn a doctorate while in the service, and would ultimately command USS Bashaw (AGSS-241) before retiring as a captain, and going on to be a world-renowned ocean scientist and explorer, with countless awards and accolades.

Trieste would subsequently be used to locate the wreckage of the lost nuclear submarine USS Thresher (SSN-593) in 1963 and, after extensive modifications would return to the site and retrieve parts of the lost submarine. Although heavily modified over the years, Trieste remains on display at the National Museum of the U.S. Navy on the Washington Navy Yard. (Trieste II [DSV-1], which examined the wreck of USS Scorpion [SSN-589] is on display at the Naval Undersea Museum in Keyport, Washington.)

It wasn’t until 2012 that anyone else attempted to dive to Challenger Deep, but in that year movie-maker/adventurer James Cameron made a solo descent in Deepsea Challenger, reaching 35,787 feet. In 2019, Victor Vescovo made a several descents in Limiting Factor to 35,843 feet, which would be the world record deepest dive, 52 feet deeper than Trieste.

Sources include: “It was Just a Longer Day at the Office—an Oral History with Don Walsh,” 16 November 2016 at science.dodlive.mil; “The First Deepest Dive” by Norman Polmar and Lee J. Mathers in January 2020 Proceedings; NHHC Dictionary of American Fighting Ships (DANFS); and biography of CAPT Don Walsh in the NHHC Archives.