H-035-2: Mediterranean Theater Catch-up

When I last covered U.S. naval operations in the Mediterranean, the United States and Allies had successfully conducted the amphibious landings at Salerno on the mainland of Italy despite attacks by German aircraft with radio-controlled bombs and by German U-boats, which made the Salerno landings one of the costliest battles for the U.S. Navy in World War II (over 800 Sailors killed). Please see H-Gram 021 for more details.

The U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, especially CNO Admiral Ernest J. King, had never been enthusiastic about invading Italy to begin with. However, since the British refused to budge on conducting an invasion of northern France before 1944, the U.S. leadership somewhat grudgingly went along with it (since British Prime Minister Winston Churchill pushed so hard for it) rather than have the increasingly large number of U.S. troops arriving in the European theater sitting around and doing nothing for a year. Although the large port city of Naples quickly fell, the Allied advance toward Rome in the winter of 1943–44 quickly bogged down—as the U.S. commanders had feared. Although the Germans gave up Naples without much of a fight, they executed one of the most thorough sabotage operations in history against the port and city infrastructure (including the city’s water and food supplies), leaving the port useless for many months and the Allies responsible for the care and feeding of tens of thousands of Neapolitan civilians. (Not helpful was the eruption of the volcano Mt. Vesuvius in March 1944, which destroyed several outlying villages. Although there were no casualties in the eruption, between 78 and 88 U.S. Army Air Forces B-25 bombers were effectively destroyed by the effects of hot ash on them at Pompeii Airfield).

Forgotten Valor: Ensign “Kay” Vesole, USNR, and the “Great Bari Air Raid,” 2 December 1943

With the port of Naples largely out of commission, the port of Bari (on the Adriatic coast of Italy) became even more critical to supply the Allied forces bogged down in heavy fighting against determined German resistance in the mountains between Naples and Rome, especially near the famed monastery of Monte Cassino. Bari had initially fallen to the British 1st Airborne Division with no opposition on 11 September 1943, and had been rapidly transformed into a major cargo and personnel off-loading facility, servicing ships of numerous nationalities, including U.S. Liberty ships. For several weeks, there was only ineffective German air resistance to Allied efforts to clear Naples and conduct logistics operations at Bari. As a result (and also due to Air Force “doctrine”), almost all Allied fighters operating in the Italian theater were committed to escort offensive bomber operations or to offensive fighter sweeps.

So weak had German air opposition been that on 2 December 1943 (although Naples harbor had been hit four times in the previous month), the British commander responsible for the air defense of Bari, Air Marshal Sir Arthur Coningham, held a press conference during which he stated “I would consider it a personal insult if the enemy should send so much as one plane over the city.” That afternoon, a German Me-210 twin-engine fighter-bomber flew a reconnaissance mission over Bari. That evening, 105 German twin-engine Junkers Ju-88 bombers of Luftflotte 2, under the command of Generalfeldmarschall Wolfram von Richthofen (cousin of the “Red Baron” of World War I) attacked Bari with devastating result.

Most of the German aircraft launched from airfields in northern Italy, but flew a circuitous route over the Adriatic and over German-occupied Yugoslavia, where they were joined by additional German bombers, and then attacked Bari from the east. At 1925 local, two or three of the bombers commenced dropping chaff and flares, which weren’t needed, as surprise was complete and the port was already fully illuminated to facilitate around-the-clock off-loading. The U.S. Liberty ship SS John Bascom was the first of over 30 ships in the harbor to open fire, but it would do little good. The Germans literally had a field day, crisscrossing the port, bombing at will, which resulted in several massive explosions of ships carrying ammunition and chain reactions, as well as severing the bulk petrol line on the quay, sending a massive sheet of flaming fuel across the harbor that engulfed undamaged ships. Different accounts give different numbers (depending on the size of the ships counted), but about 28 ships were lost (including three that didn’t sink, but were a total loss due to severe damage—although their cargoes were salvaged) and another 12 received varying degrees of damage. These ships included American, British, Polish, Norwegian, and Dutch-flagged vessels. Exact casualties are unknown, but some estimates are as high as 1,000 crewmen killed aboard the ships and military personnel on the docks and another 1,000 civilians killed in the city. Five U.S. Liberty ships were sunk, with the loss of about 75 U.S. Merchant seaman and 50 U.S. Navy Armed Guards.

The U.S. Liberty ship SS John Harvey was hit by a bomb and exploded, killing all 36 crewmen, ten U.S. soldiers, and 20 U.S. Navy Armed Guards aboard. Worse, John Harvey was carrying a secret cargo of 2,000 M47A1 mustard gas bombs (to be used in retaliation in the event the Germans resorted to the use of chemical weapons). Liquid sulfur agent mixed with the fuel oil coating the surface of the harbor and a cloud of sulfur mustard was blown over the city of 250,000 civilians. The exact number of casualties due to the chemicals is not known (especially civilian casualties), and many were caused because no one was prepared for it; neither victims nor medical personal initially recognized or correctly diagnosed the symptoms. Some of the deaths could have been prevented by simple freshwater washdown of oil-coated sailors and disposal of contaminated clothing. That the equipment for a U.S. hospital was also destroyed in the bombing compounded the tragedy. At least 628 patients and medical personnel came down with symptoms of chemical poisoning and at least 83 died by end of month. Of these known gas casualties, 90 percent were U.S. merchant seaman. The event was initially kept secret because the United States did not want the Germans to know that chemical weapons had been brought into the theater, which might provoke German use. However, in February 1944, the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff issued a statement admitting what had happened, although records were not fully declassified until 1959. This was the only known poison gas incident in World War II.

The U.S. Liberty ship SS John L. Motley was hit by three bombs, which detonated her cargo of ammunition in a massive blast that killed almost everyone aboard, including 36 crewmen and 24 U.S. Navy Armed Guard personnel. Five Armed Guards somehow survived, as well as four crewmen ashore. The U.S. Liberty ship SS Samuel Tilden was hit by an incendiary bomb forward of the bridge, and another bomb that penetrated into her engineering spaces, and she was hit by German strafing and “friendly” anti-aircraft fire. Ten of her crew, 14 U.S. soldiers, and three British soldiers were killed aboard, and she was so badly damaged she had to later be scuttled by torpedoes from a British destroyer. The U.S. Liberty ship SS Joseph Wheeler was also sunk, with a loss of 26 crewmen and 15 U.S. Navy Armed Guard. The U.S. Liberty ship SS Lyman Abbott was damaged, killing one U.S. Army soldier and one U.S. Navy Armed Guard. The U.S. Liberty ship SS John M. Schofield also received damage.

The explosion of the SS John Motley caved in the side of the U.S. Liberty ship SS John Bascom, which, coupled with three bomb hits, caused her to sink with the loss of four crewmen and ten U.S. Navy Armed Guard. Ensign Kopl K. “Kay” Vesole, USNR, would be awarded a posthumous Navy Cross for:

“…extraordinary heroism and distinguished service in the line of his profession as the Commanding Officer of the Armed Guard aboard the SS JOHN BASCOM when that vessel was bombed and sunk by enemy aircraft in the harbor of Bari, Italy, on the night of 2 December 1943. Weakened by loss of blood from an extensive wound over his heart and with his right arm helpless, Ensign Vesole valiantly remained in action, calmly proceeding from gun to gun, directing his crew and giving aid and encouragement to the injured. With the JOHN BASCOM fiercely ablaze and sinking, he conducted a party of his men below decks and supervised the evacuation of wounded comrades to the only undamaged lifeboat, persistently manning an oar with his uninjured arm after being forced to occupy a seat in the boat (he had tried to swim to make room for other wounded, but his crew forced him into the boat), and upon reaching the seawall, immediately assisted in disembarking the men. Heroically disregarding his own desperate plight as wind and tide whipped the flames along the jetty, he constantly risked his life to pull the wounded out of flaming oil-covered waters and, although nearly overcome by smoke and fumes, assisted in removal of casualties to a bomb shelter before the terrific explosion of a nearby ammunition ship inflicted injuries that later proved fatal. (He had to be restrained from going into the flames to rescue others; he also refused to get in the first boat that came to rescue them from the jetty where they were all trapped by the flames, and was forced into the second). The conduct of Ensign Vesole throughout this action reflects great credit upon himself, and was in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service. He gallantly gave his life for his country.”

Ensign Vesole was a Polish immigrant to the United States, and had previously saved a man from drowning while attending the University of Iowa, where he earned a law degree. He was a practicing lawyer when he joined the Naval Reserve. Upon his death, he left a wife and baby he had never seen, with his last words being “I’ve a three-month-old baby at home. I certainly would like to see my baby.”

Operation Shingle: The Allied Landings at Anzio, Italy, January–June 1944

With the Allies and the Germans deadlocked in months of bloody combat in the rough terrain (which favored defense) between Naples and Rome, a plan to conduct an amphibious operation at Anzio and Nettuno on the western Italian coast north of Gaeta gained the strong backing of British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. It would turn out to be one of the most ill-conceived operations of the entire war, resulting in a months-long stalemate of U.S. and British Army forces pinned down on the beachhead. The Anzio landings were too far behind the German lines with insufficient force. The Germans were quickly able to shift enough forces to continue to hold their defensive line in the mountains, while at the same time hemming in the Allied beachhead and preventing either Allied force from aiding the other. Constant German air attacks took a toll of Allied forces ashore and a significant number of warships, mostly British, which were also tied to the beachhead attempting to provide gunfire support to the troops. The actual amphibious landing actually went very well; it was what happened afterward that was nearly a disaster.

At the various major Allied planning conferences in 1943, some of the most contentious arguments concerned the allocation of tank landing ships (LSTs), which proved to be the long pole in the tent for a number of planned amphibious operations. The United States continued to push for the earliest possible invasion of northern France, while the British steadfastly resisted, with Churchill (from the U.S. perspective) intent on beating around the Mediterranean bush. Finally, after intense “negotiations,” the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff reluctantly agreed to retain 68 of the 90 LSTs in the Mediterranean, although initially that was considered insufficient to transport enough troops for an effective amphibious landing behind the German defensive lines, and to sustain the Allied forces in the face of almost certain German counterattacks.

The Anzio plan got a boost, when at the Cairo Conference (SEXTANT) in late November 1943 a long-planned British amphibious assault in the Andaman Islands in the Indian Ocean was formally cancelled, freeing an additional 15 LSTs for the Mediterranean. (The purpose of the Andaman operation was to assist with the opening of a ground supply route to China via Burma, something that CNO King supported in his hope to ultimately use Chinese manpower in the final defeat of Japan). Nevertheless, the Anzio operation was on-again off-again (cancelled on 22 December 1943 and revived on 23 December 1943 at Churchill’s insistence).

In November 1943, Rear Admiral John L. Hall, USN, commander of VIII Amphibious Force, was designated as the overall Allied naval commander for the Anzio landings, although he would be replaced by Rear Admiral Frank J. Lowry in December. U.S. Army Major General John P. Lucas was designated commander of the VI Corps (initially one U.S. and one British division, along with several battalions of U.S. Ranger and British commando forces, and a U.S. airborne regiment) to conduct the landings. (Eventually six divisions would be needed just to hold the beachhead, as four German divisions were able to quickly counter the landings). Lucas was pessimistic about the operation from the very beginning. His pessimism wasn’t helped when the U.S. rehearsal for the landings on 17–18 January turned into a total fiasco, during which rough seas swamped 40 DUKW amphibious trucks, resulting in the loss of many of the 105-mm howitzers intended to support the initial amphibious assault. The plan also called for a major operational deception effort, including diversionary shore bombardments and air strikes near the German-occupied Italian port of Leghorn (Livorno), which appeared to have absolutely no effect on the Germans.

After many delays, D-day for Operation Shingle was set for 0200 on 22 January 1944 (sunrise was at 0731). As had been the case for every Mediterranean amphibious landing to that point, the U.S. Army insisted on a night assault with minimal pre-landing shore bombardment to maintain the element of surprise. The night assaults invariably resulted in confusion and delay among the landing craft and support vessels, and the landings at Anzio would start out the same way.

The Anzio assault force was designated Task Force 81, under the command of Rear Admiral Lowry, embarked in USS Biscayne (AGC-3), a seaplane tender reconfigured as an amphibious force command ship. Lowry was also in command of the X-Ray Force, tasked with landing the U.S. 3rd Infantry Division (commanded by Major General Lucian Truscott). The gunfire support group (TG 81.8) included the light cruisers USS Brooklyn (CL-40) and HMS Penelope, escorted by several U.S. and British destroyers and destroyer escorts. Task Force Peter, commanded by Rear Admiral Thomas Troubridge, RN, was responsible for landing the British 1st Infantry Division, and was supported by the cruisers HMS Orion and HMS Spartan, and several British destroyers.

The initial assault on Anzio was spearheaded by U.S. Army Rangers, embarked on British infantry landing ships (LSIs). However, the rocket-configured tank landing craft (LCT-147—798 rocket tubes) that was supposed to support the Rangers’ assault, arrived late and opted not to fire for fear of hitting the Rangers, while the Rangers delayed while waiting for the LCT to fire. It turned out not to matter, as the beach chosen was neither mined nor defended, and the Rangers achieved complete tactical surprise, capturing the Anzio mole before the Germans could sabotage it. By 0645, all Rangers were ashore.

The British landings (Task Force Peter) started reasonably well as the beacon submarine HMS Ultor guided the force in, but was subsequently delayed by extensive mines on the beach. This caused 18 LSTs and 24 LCIs from Naples to mill about, during which time the HMS Palomares (originally a banana boat, but re-configured as an anti-aircraft and fighter-direction ship) hit a mine and had to be towed to Naples. German artillery opened up and hit a few of the British LSTs, fortunately with minimal damage, but the beach was determined to be “too hard,” and the British landings shifted to the U.S. beaches further north.

The U.S. landings at the “X-ray” beaches (Red and Green) started well, as the guide sub HMS Uproar led 23 minesweepers in, which found few mines. At 0153, two British LCT rocket ships assigned to support the U.S. X-ray landings opened fire, which proved effective at detonating German mines on the beach. The initial U.S. waves on landing craft met no opposition. However, at 0239, LCI-211 in the third wave ran aground on a false beach, and as other landing craft closed in to help, heavy machine-gun fire from the beach inflicted numerous casualties. Nevertheless, by 0634, eight waves of landing craft had reached shore with minimal troop losses.

As the Germans had been taken by surprise, there were initially few calls for Navy gunfire support. The destroyer USS Mayo (DD-422) fired on some targets at 0748, but Brooklyn mostly milled about smartly awaiting calls. The first (of what would be many) German air attacks commenced after dawn. Six Messerschmitt fighters were followed by several Focke-Wulf fighter bombers that hit and sank USS LCI-20 with a bomb about the same time as the minesweeper USS Portent (AM-106) struck a mine and sank with the loss of 18 crewmen. Nevertheless, by midnight of D-day, 36,034 men, 3,069 vehicles, and 90 percent of the assault load were ashore. Both divisions and the Rangers were ashore and engaging German forces.

Compared to the disastrous rehearsal, the actual Anzio landing was a great success, aided considerably by fair weather and complete surprise (the Germans at Anzio had actually been at a high state of alert, but had cancelled it the night before the assault, apparently fooled by the Allied delays). However, the German senior commander in Italy, Generalfeldmarschall Albert Kesselring, had a pre-planned response ready and with one code word (“Richard”) set it in motion. And, despite Allied air attacks, the Germans had little problem moving to counter the landings.

To that point, all pretty much seemed to be going according to the Allied plan. On 23 January, Brooklyn was finally called upon to interdict German troop movements, as it became increasingly apparent a German counterattack was in the offing. Gunfire from destroyer USS Trippe (DD-403) broke up a German counterattack. However, at dusk, a 55-plane German air raid came in. Destroyer HMS Janus was hit by an aerial torpedo, broke apart, and capsized with a loss of 159 crewmen. Destroyer HMS Jervis was hit by a radio-controlled bomb, but suffered no casualties and was able to make Naples under her own power. However, as a result of a command-and-control mix-up, the British cruisers all withdrew, leaving Brooklyn alone the next morning, resulting in a low point in Anglo-American relations. (As an aside, future comedian Lenny Bruce served as a sailor aboard Brooklyn in World War II).

The next evening, on 24 January, several waves of German aircraft attacked. Brooklyn suffered several near misses, but escaped significant damage. The minesweeper USS Prevail (AM-107) was put out of action by a near miss. Destroyer USS Plunkett (DD-431) was simultaneously attacked from different directions by two radio-controlled glide bombs and two Ju-88 bombers, followed by several more bombers. Plunkett out-maneuvered the glide bombs, but, after a 17-minute duel with the bombers, was finally hit by one 550-pound bomb that started a serious fire, killing 53 crewmen. However, Plunkett was able to reach Palermo, Sicily, under her own power. In the meantime, the destroyer Mayo, which had conducted numerous gunfire support missions throughout the day keeping German ground forces from crossing the Mussolini Canal, hit a mine, which nearly broke her in two, killed seven, holed the starboard side, and damaged the propeller shaft, resulting in loss of steering control. Mayo was towed to Naples by a British tug and was the fourth Allied destroyer knocked out in 24 hours. (Mayo was repaired and went on to serve until 1972). The German air attack also worked over three clearly marked British hospital ships, which suffered numerous near misses, and caused the St. David to sink with loss of life.

On 25 January 1944, U.S. Army radio intercept operators embarked on destroyer escort USS Frederick C. Davis (DE-136) intercepted a German aircraft reconnaissance report, providing early warning of impending airstrikes. Frederick C. Douglas was also equipped with special equipment to jam German radio-controlled bombs. She would remain on station off Anzio under frequent air attack and occasional shore battery fire almost continuously for the next six months, for which she would be awarded a Navy Unit Commendation. (She would survive Anzio, only to be torpedoed and sunk while attacking a German U-boat in the Atlantic on 24 April 1945 with a loss of 115 of her crew, the last U.S. destroyer/destroyer escort lost in the Atlantic.) Although the British cruiser HMS Orion returned with additional naval reinforcement the same day, the small minesweeper USS YMS-30 struck a mine and quickly sank with the loss of 17 (about half) of her crew.

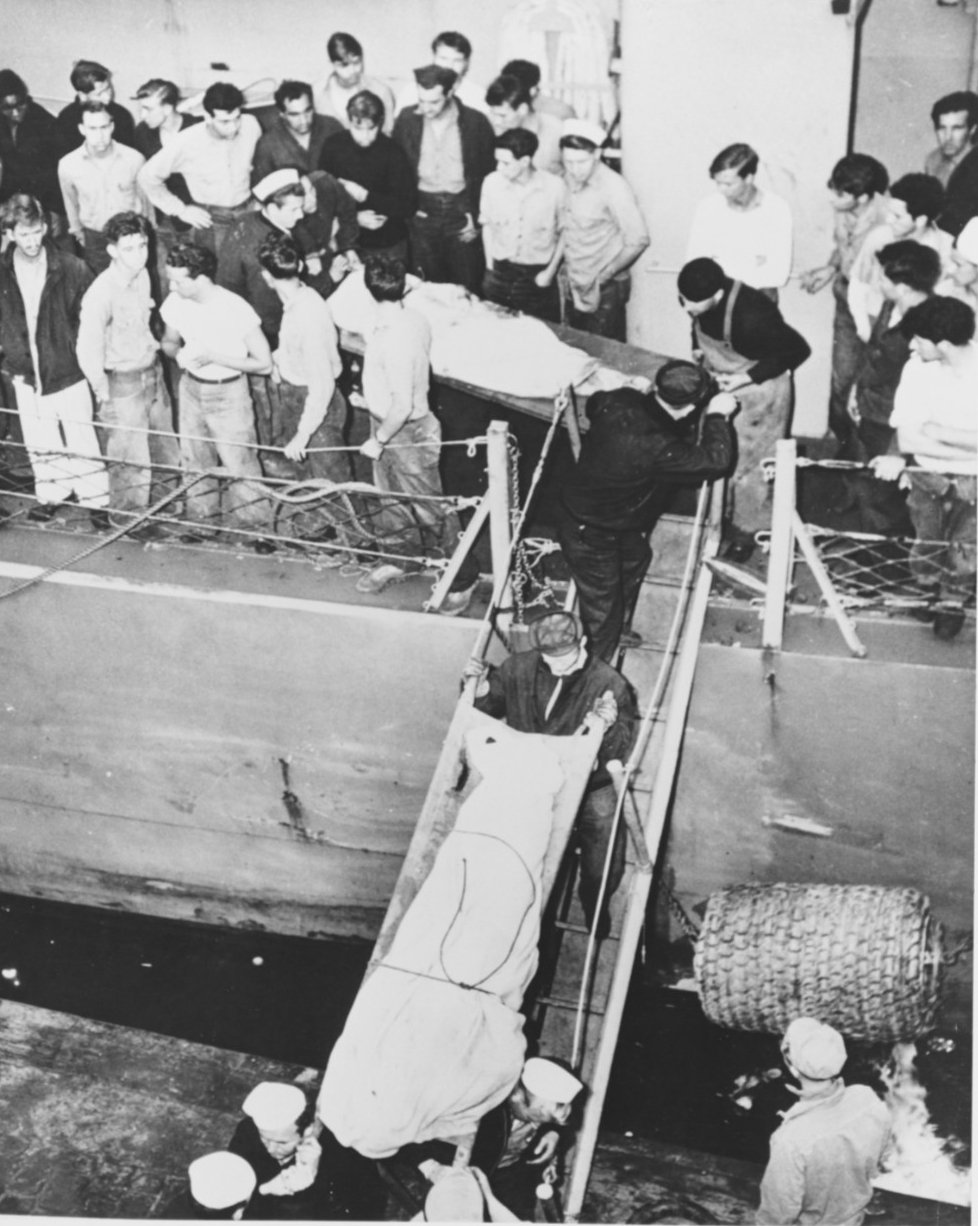

The steady drain of Allied naval losses continued and took a tragic turn. On 26 January 1944, the British LST-422 (carrying U.S. troops and equipment) was blown into a known minefield by gale-force winds, struck a mine, and caught fire. Over 400 U.S. troops were caught between the raging inferno and the frigid sea as the ship made any decision moot as she broke in two and sank with the loss of 454 U.S. soldiers (mostly from the U.S. 83rd Chemical Battalion) and 29 British crewmen. As U.S. LCI-32 came to the rescue, she too struck a mine and sank in three minutes, with 30 of her crew killed and 11 wounded. A total of 150 survivors were rescued from the two ships. At dusk, a German Focke-Wulf fighter damaged HMS LST-366. The U.S. Liberty ship SS John Banvard suffered a close and damaging near miss from a radio-controlled bomb and the master ordered abandon ship. However, the U.S. Navy Armed Guard re-boarded the vessel, manned the guns, and continued to fight off a second wave of attacks. John Banvard amazingly suffered no casualties and remained afloat, but she would be written off as a total loss. In addition, a presumably damaged German aircraft crashed into the freighter Hilary A. Herbert, which was then barely missed by a bomb and had to be beached to prevent sinking. U.S. commanders off Anzio began to complain about the lack of Allied air cover, as the U.S. Army Air Forces’ strategy of “isolating the battlefield” by attacking lines of communication was doing nothing of the kind, ashore or afloat. And, the weather continued to deteriorate.

As the Allied advance from Anzio and Nettuno beachhead quickly bogged down in the face of determined German resistance and frequent counterattacks, the situation ashore turned into a bloody stalemate for months. Allied naval forces were compelled to remain offshore during this period, which lasted from about 28 January to 30 April 1944.

Destroyer escorts Frederick C. Davis and Herbert C. Jones (DE-137), and HMS Ulster Queen (an auxiliary anti-aircraft cruiser) had embarked fighter-direction teams, powerful jamming gear to counter radio-controlled bombs, and radio-intercept and -monitoring capability to provide early warning. (Herbert C. Jones would also receive a Navy Unit Commendation for her work off Anzio). Despite this, an air strike on the evening of 29 January struck the British cruiser HMS Spartan with a radio-controlled Hs-293 glide bomb. The German aircraft evaded radar detection by flying low over land and attacking ships silhouetted by the afterglow of the sunset (the smoke screen was ineffective due to high winds). The damage to Spartan was severe, and after an hour she rolled over and sank with the loss of 65 of her officers and crew. In addition, the U.S. Liberty ship SS Samuel Huntington was hit by a glide bomb, which ignited her cargo of ammunition and gasoline, and blasted a jeep through her flying bridge. Four crewmen were killed in the bomb hit. The master quickly ordered abandon ship and the rest of the crew got away in lifeboats before the ship exploded, raining shrapnel on ships up to a mile and a half away, and sank in shallow water.

Despite the losses, in the first week of Operation Shingle, seven Liberty ship and 201 LST loads had been put ashore along with 68,886 troops, 237 tanks and 508 artillery pieces, about four divisions worth, which, however, would not be enough. Allied warships continued to blunt German ground attacks, with destroyer USS Edison (DD-439) given credit for very effective fire, killing many German troops on the night of 29–30 January. In addition, the previously damaged light cruiser USS Brooklyn, with her rapid-fire 6-inch guns, returned to the action. On 1 February, Rear Admiral Lowry on Biscayne departed, handing over command of the naval forces offshore to the British. General Lucas noted, “The work of the Navy under his [Lowry’s] direction has been one of the outstanding achievements of the operation.”

Throughout February, heavy German attacks ashore kept the Allied VI Corps on defensive, sometimes threatening to break through to the beach, often being driven back by effective naval gunfire. On 8 February 1944, the destroyer USS Ludlow took a hit from a German 5-inch artillery shell that hit the bridge at a 60-degree angle and passes between the legs of the commanding officer, Commander Liles Creighton, as he was sitting in his chair on the bridge, and down into the ship, but failed to explode. Chief Gunner’s Mate James D. Johnson located the live shell and threw it overboard. Creighton suffered severe burns to his legs, but survived (demonstrating an evolutionary advantage of “man-spreading”).

By 16 February, the light cruiser USS Philadelphia (CL-41) replaced Brooklyn, providing gunfire support. On that day, the U.S. Liberty ship SS Elihu Yale was hit by a radio-controlled bomb. Although the bomb hit in an empty hold, it set off ammunition that had been off-loaded onto LCT-35, which resulted in the loss of both vessels, with Elihu Yale settling in very shallow water.

On 22 February, Major General Lucas took the fall for the badlyconceived operation and was fired. Lucas came in for considerable criticism over the years for essentially “hunkering down” once his forces were ashore rather than aggressively attacking. The reality is that either way he lacked sufficient combat power against more numerous and highly capable German forces operating from highly defensible terrain, and too far from the main Allied forces north of Naples for mutual support. Lucas was relieved by 3rd Infantry Division commander Major General Truscott, which made no difference. Churchill was later to complain, “I had hoped we were hurling a wildcat onto the shore, but all we got was a stranded whale.” In addition, the step-son of U.S. Army Chief of Staff, General George C. Marshall, was killed at Anzio.

Somewhat surprisingly, neither the Germans nor Italian forces that sided with the Germans conducted attacks by submarine or motor torpedo boats during the first weeks of the operation. That changed on 18 February, when several Italian torpedo boats attempted an attack but were driven off by U.S. patrol craft, which sank two of the enemy. That same day, the British light cruiser HMS Penelope departed Naples en route Anzio and was struck by a torpedo from U-410 that hit her after engineering room. Sixteen minutes later, she was hit by another torpedo from U-410 in her after boiler room, with catastrophic effect. Penelope took her commanding officer and 417 of her crew to the bottom (206 survived). On 20 February, U-410 struck again, sinking U.S. LST-348 with two torpedoes. The first torpedo blew off her bow, and the second broke her in two; 43 of her crew were lost. On 25 February, the British destroyer HMS Inglefield was struck by an Hs-293 glide bomb and sunk with a loss of 35 of her crew (157 were rescued). On 30 March, the British destroyer HMS Laforey was torpedoed and sunk by U-223, with a loss of all but 65 of her 246 crewmen.

The stagnation ashore continued from March through April, fortunately without additional significant Allied naval losses. German midget submarines made their first appearance off Anzio on 21 April, but three were quickly sunk by U.S. patrol craft. Finally, in early May 1944, Allied forces had worn down the Germans enough to attempt a breakout. This commenced on 11 May 1944, supported by gunfire from U.S. light cruisers Philadelphia, Brooklyn, British cruiser HMS Dido, and several U.S. destroyers, which fired hundreds of rounds at the Germans. At one point, on 13 May, however, accurate German artillery fire caused several near misses to Brooklyn, forcing her to retire for a time. On 14 May, German aircraft tried a new tactic, dropping torpedoes in Naples harbor that ran in circles, fortunately hitting no ships. Off Anzio, PC-627 sank an Italian torpedo boat. That same morning, Philadelphia and destroyers Boyle (DD-600) and Kendrick (DD-612) were providing gunfire support near Gaeta (south of Anzio) to U.S. forces that had finally broken through the German defensive line and were advancing northward along the coast to link up with the Allied forces at Anzio.

On 22 May 1944, the destroyer USS Laub (DD-613) and Philadelphia collided, forcing both to withdraw for temporary repairs. However, the good news was that German defenses between Anzio and Rome collapsed, and the Germans gave up Rome without a fight, fortunately without the extensive sabotage and destruction they had inflicted in Naples. The French cruiser Émile Bertin assumed naval gunfire support duties from the U.S. cruisers. Rome fell to the Allies on 4 June, and event that was immediately overshadowed by the Allied landings in Normandy on 6 June 1944.

Operation Shingle was a costly victory. Over 2,800 U.S. soldiers were killed and 11,000 wounded, while the British Army suffered 1,600 killed and 7,000 wounded. The Royal Navy paid more heavily than the U.S. Navy. The Royal Navy lost two cruisers, three destroyers, three LSTs, one LCI, and one hospital ship, with 366 Royal Navy personnel killed (this number does not appear to include those lost—over 400—on HMS Penelope, although she is one of the two British cruisers listed as lost in the campaign). The U.S. Navy lost one minesweeper, one small mine craft, one LST, two LCIs, three LCTs, and two Liberty ships (plus quite a few more ships damaged) with 160 U.S. Navy personnel killed and 166 wounded. The Germans ashore suffered about 5,000 dead.

Convoy Battles Along the Algerian Coast, April–May 1944

Just before midnight on 11 April 1944, while laying smoke ahead of convoy UGS 37 transiting easterly along the coast of Algeria, the destroyer escort USS Holder (DE-401) was struck portside amidships by an aerial torpedo from a German bomber. This resulted in two heavy secondary explosions and extensive fire and flooding. Despite the severe damage, Holder’s gunners continued to defend the convoy, driving off other attackers without any additional damage to the convoy. Lieutenant Commander G. Cook’s crew got the fire and flooding under control and the ship was towed into Oran, Algeria, and then to New York, where the damage was considered to be too severe to repair.

On the evening of 20 April 1944, following an unsuccessful attack by German submarine U-969, Allied convoy UGS 38 (87 ships), carrying ground personnel and supplies to Italy, was attacked by about three waves of German Ju-88 and Heinkel He-111 twin-engine bombers (18–24 total according to U.S. reports) north of Algiers, Algeria. Flying low to avoid radar detection, the Germans attacked simultaneously from multiple axes after dark. The U.S. Liberty ship SS Paul Hamilton was struck by a torpedo from one of the bombers, and suffered a catastrophic explosion that killed all 580 personnel aboard; the ship sank in less than 30 seconds and only one body was recovered. The dead included eight officers and 39 crew of the ship, 29 U.S. Navy Armed Guards, 154 personnel of the USAAF 831st Bombardment Squadron (a B-24 heavy bomber squadron) and 317 personnel of the 32nd Photo Reconnaissance Squadron. It is possible that gunners on Paul Hamilton violated procedure, opening fire too soon and drawing attention to the ship among the many in the convoy. The explosion of Paul Hamilton was one of the most famous photographs of the war.

The flames from Paul Hamilton silhouetted the destroyer USS Lansdale (DD-426), which had been acting as “jam ship” against German radio-controlled bombs. The jamming gear was of no use against German aerial torpedoes, and Lansdale was attacked from port and starboard at the same time. Lansdale maneuvered to avoid two torpedoes launched by Heinkels on the port side, both of which missed. Lansdale then maneuvered to counter five Heinkels coming in from starboard. Lansdale shot one down which crashed astern. Another Heinkel launched its torpedo before being hit by Lansdale, passing over the forecastle before crashing on the opposite side. However, the torpedo struck Lansdale on the starboard side in the forward fireroom at 2106, blowing large holes in both sides of the ship and almost splitting her in two.

With a 12-degree list and her rudder jammed hard to starboard, Lansdale continued to fight, knocking down one of two more torpedo planes that attacked, and both torpedoes missed. The crew fought hard to save the ship, correcting the steering casualty, but, by 2122, the list reached 45 degrees, and her commanding officer, Lieutenant Commander D. M. Swift, ordered abandon ship. At 2130, Lansdale rolled on her side and then broke in two; the stern section immediately sank. Forty-seven officers and crewmen were lost with the ship. During the course of the attack, another merchant in the convoy was torpedoed and abandoned, but later re-boarded and saved, and two more merchant ships were hit by torpedoes and one was sunk.

During the night, the destroyer escort USS Menges rescued 137 survivors of Lansdale, plus two downed German aircrew, and the destroyer escort USS Newell rescued 119, including Lieutenant Commander Swift. One of the survivors of Lansdale was the executive officer, Robert M. Morganthau. Morganthau was born into great wealth and privilege (his father was President Roosevelt’s treasury secretary, his grandfather was President Wilson’s ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, and Robert raced sailboats with future President John F. Kennedy). Nevertheless, Morganthau was imbued with the spirit of public service, and he joined the U.S. Naval Reserve V-12 Program while still in college before the war. He was activated and served for four and half years aboard four destroyers and a destroyer-minelayer. He passed his physical exam for the Navy by concealing his near-deafness in one ear, which had been caused by a childhood infection.

After surviving the sinking of Lansdale, Morganthau went on to be the executive officer of the new destroyer-minelayer, USS Harry F. Bauer (DM-26). Harry F. Bauer shot down 13 Japanese aircraft during nearly two months of near-continuous kamikaze attacks in early 1945 and was hit by several bombs and a torpedo, all of which failed to explode, before suffering a glancing blow from a kamikaze. An unexploded bomb from the kamikaze lodged in the fuel tank, unbeknownst to any of the crew, for 17 days before it was found and disarmed (barely). Morganthau battled institutional anti-Semitism in the Navy and as executive officer stood his ground with the commanding officer in insisting that black sailors be allowed to man anti-aircraft guns. He also prevailed in having several of them awarded Bronze Stars when they stood by their gun near the kamikaze flames while others sought shelter (Harry F. Bauer would be awarded a Presidential Unit Citation).

Years later, Morganthau reflected on his time in the water off Lansdale, “I was swimming around without a life jacket. I made a number of promises to the Almighty, at a time when I didn’t have much bargaining power.” His deal? “That I would try to do something useful with my life.” After the war, he went to Yale Law School and went on to serve for more than four decades as the chief federal prosecutor for southern New York State (nine years) and as Manhattan’s longest-serving district attorney (35 years), putting thousands of criminals behind bars. He passed away on 21 July 2019 at age 99.

Just after midnight on 3 May 1944, the destroyer escort USS Menges (DE-320), which had rescued many of the survivors of Lansdale on the night of 20–21 April, detected and attacked German submarine U-371, but was hit by a G7es acoustic homing torpedo counter-fired by the U-boat. The aft third of Menges was virtually destroyed, 31 crewmen were killed, and 25 wounded. Despite the grievous damage, Menges’s skipper, Lieutenant Commander Frank M. McCabe, USCG, refused to order abandon ship, and his almost entirely U.S. Coast Guard crew managed to keep her from sinking, including several who heroically jumped astride torpedoes that had come loose to prevent them from exploding. Menges was towed to Bougie (Béjaïa), Algeria, while other convoy escorts USS Joseph E. Campbell (DE-70), USS Pride (DE-323), and British and French escorts pursued U-371. On 4 May, they finally forced the U-boat to scuttle herself, but not before she put a torpedo into French destroyer escort Senegalais (a U.S. Canon-class destroyer escort seconded to the Free French Navy), which survived. Menges was towed to New York, where her mangled stern was removed and replaced by that from the damaged USS Holder (DE-401) with repairs complete in October 1944. Menges then joined a four-ship hunter-killer group in the Atlantic, the only such group composed entirely of Coast Guard–manned U.S. Navy ships. McCabe was awarded a Legion of Merit for the rescue of Lansdale’s crew and for saving his ship from the torpedo hit.

On 5 May 1944, while escorting westbound convoy GUS 38 off Oran, Algeria, the destroyer escort USS Fechteler (DE-157) was hit by a torpedo from German submarine U-967, broke in two and sank, suffering 29 killed and 26 wounded. USS Laning (DE-159) rescued 186 survivors. Fechteler had previously survived a heavy German air attack on 20 April 1944. U-967 was one of the last surviving German submarines in the Mediterranean. During her three patrols, she only sank Fechteler. U-967 was scuttled in Toulon, France, in August 1944 during the Allied invasion of southern France.

Sources include: “Naval Armed Guard Service: Tragedy at Bari, Italy on 2 December 1943,” Naval Historical Center, 8 August 2006; History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, Vol. IX, “Sicily–Salerno–Anzio, January 1943–June 1944, by Samuel Eliot Morison, 1954. NHHC’s online Dictionary of American Fighting Ships (DANFS); and The Official Chronology of the U.S. Navy in World War II, by NHHC Historian Robert J. Cressman, 1999.