H-072-1: Torpedo Squadron 8's TBF Avenger Detachment in the Battle of Midway

On the morning of 4 June 1942, Lieutenant Langdon Kellogg Fieberling, U.S. Naval Reserve, faced the most momentous decision of his life: whether to lead his detachment of six new TBF-1 torpedo bombers in following the attack plan laid out by the commander of the Midway air group or to proceed on his own initiative to attack the Japanese carrier force. His decision would lead to a sequence of events that altered the course of the battle, and of World War II.

Lieutenant Fieberling was known to his squadron mates as “Old Langdon” because at 32, he was one of the oldest in Torpedo Squadron 8 (VT-8). He graduated from high school in 1928, worked his way through college with summer jobs as an ordinary seaman on the merchant steam ship SS Absaroka, and graduated from University of California—Berkeley sometime in 1933. He enlisted in the U.S. Naval Reserve on 7 October 1935 and reported for duty as an aviation cadet on 27 June 1936. He was commissioned an ensign (A-V[N]) on 1 March 1937. He was promoted to lieutenant (junior grade) in March 1940 and served as a flight instructor at Naval Air Station Pensacola, Florida.

On 26 July 1941, Fieberling was assigned to the newly formed VT-8, which was commissioned on 2 September 1941 under the command of Lieutenant Commander John C. Waldron. VT-8 was the torpedo squadron for the newest carrier in the U.S. fleet, USS Hornet (CV-8), commissioned on 20 October 1941. The squadron was destined to receive the new TBF-1 Avenger torpedo bomber, but was still equipped with the older TBD Devastator. When it first came into service in 1937, the TBD was the state-of-the-art torpedo bomber in the world, but aviation technology was advancing so fast that by 1941 it was already obsolete and vulnerable to improved enemy fighters (the U.S. Navy did not yet realize just how vulnerable). The TBD’s performance was also hampered by the use of the Mk. XIII aerial torpedo, which the Bureau of Ordnance refused to admit was unreliable.

VT-8 finally received 21 of the new Grumman TBF-1 aircraft, but too late to complete workups before Hornet departed Norfolk on 4 March 1942 for the Pacific to serve as the launch platform for the 16 U.S. Army Air Forces (USAAF) B-25 bombers of the Doolittle Raid (see H-Gram 004). Lieutenant Commander Waldron divided his squadron in two, with half and most of the senior pilots embarking on Hornet with the TBDs. The other half, under the charge of Lieutenant Harold “Swede” Larson, remained behind to continue working up the TBF, and consisted mostly of new Naval Reserve ensigns. (Some accounts have said that the name “Avenger” was not bestowed on the aircraft until after the Battle of Midway, but newspaper accounts at the time indicate the name was assigned just prior to Pearl Harbor. The plane was actually shown to the public for the first time on 7 December 1941, a debut that was overtaken by other news. The name, however, was not widely known or used before the Battle of Midway, the first combat action for the aircraft.)

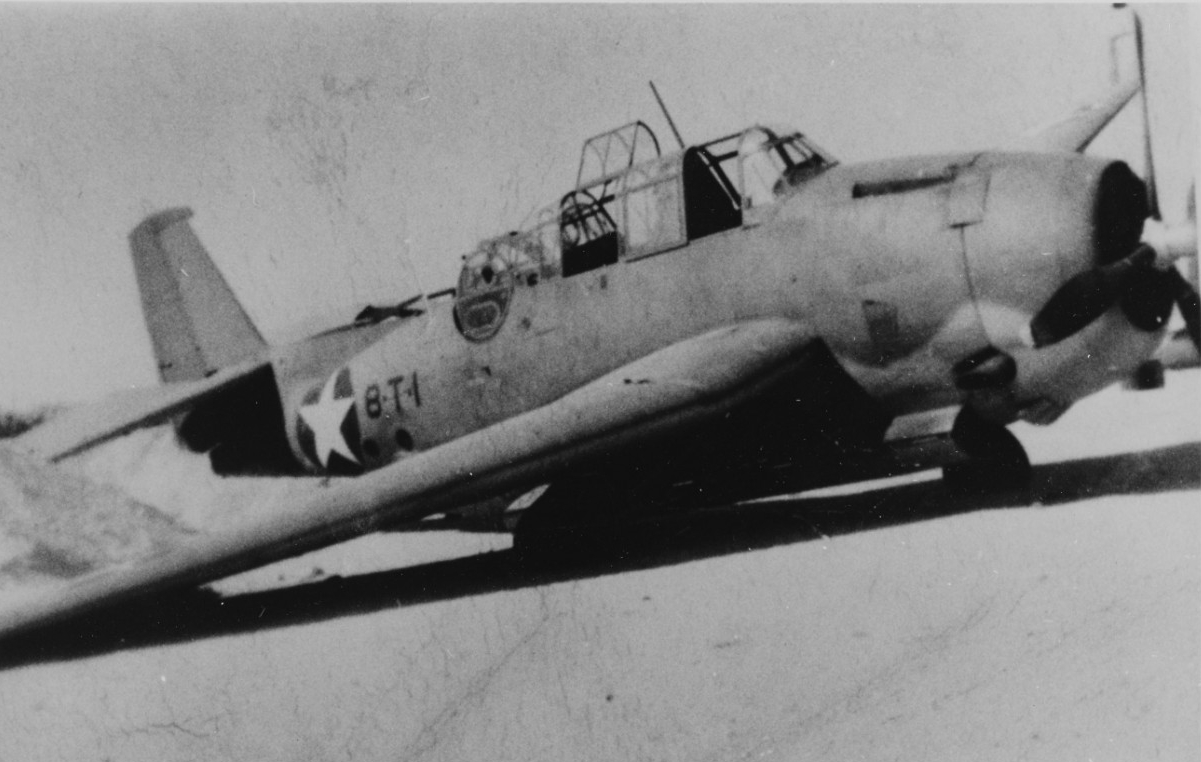

The TBF was the heaviest single-engine aircraft produced during World War II, known to carrier flight deck crewmen as the “Turkey” due to its large size and difficulty in maneuvering around the flight deck. The TBF had a new folding-wing system (“Sto-Wing” compound-angle system), so the wings would rotate and fold backward (rather than upward as in the TBD) in order to minimize the flight deck footprint. The TBF had a powerful double-row Wright R-2600-20 Twin Cyclone 14-cylinder radial engine that produced 1,900 horsepower, which could propel the plane to a maximum speed of 242 knots (compared to 179 knots for the TBD). The TBF had a range of 786 nautical miles at cruising speed. It could carry a 2,000-pound torpedo or bomb (or up to four 500-pound bombs) in an internal bomb bay.

TBFs had a crew of three. The pilot controlled a .30-caliber machine gun mounted in the nose. The gunner had a .50-caliber machine gun in an aft-facing, electrically controlled dorsal turret. The radioman/bombardier operated a .30-caliber machine gun from a ventral position to deal with attacks from behind and below. During the war, a number of different models of the TBF would be produced with upgraded armament, electronics, and flight characteristics. When Grumman shifted emphasis to producing the F6F Hellcat fighter, production of the Avenger shifted to General Motors Eastern Division, and the aircraft were given the “TBM” designation.

In early May 1942, Lieutenant Larson led the VT-8 TBFs in a cross-country flight from Norfolk to San Diego, and then to Alameda, California. The aircraft were loaded on the transport ship USS Hammondsport (APV-2) and the squadron personnel embarked USS Chaumont (AP-5). Hammondsport reached Pearl Harbor first and was already offloading aircraft when Chaumont arrived on 29 May 1942.

Hornet, with the rest of VT-8, had left the day before the arrival of the TBF detachment. The carrier was to rendezvous with Enterprise (CV-6) and proceed to Point Luck, the intended ambush point for the anticipated Japanese attack on Midway. This departure timing was critical, as it enabled Hornet and Enterprise to pass through the location of the Japanese submarine scouting line before it was formed—because the Japanese submarines were delayed. Yorktown (CV-5) also made it through undetected after completion of emergency repairs to her Coral Sea battle damage (see H-Grams 005 and 071 for more on the Battle of the Coral Sea).

In anticipation of the Japanese attack on Midway, the island’s air defenses continued to be upgraded, with additional guns and aircraft. On Sunday 31 May, Fieberling received orders to lead a flight of six TBFs to Midway, a distance of about 1,200 miles. The flight would be a feat in itself. With their carrier gone, virtually the entire squadron volunteered for the mission. The pilots selected for this mission by Lieutenant Larson were Ensign Oswald “Ozzie” Gaynier, Ensign Albert K. “Bert” Earnest, Ensign Victor A. “Vic” Lewis, Ensign Charles E. “Charlie” Brannon, and enlisted pilot Aviation Machinist’s Mate First Class Darrell D. Woodside. Because the VT-8 pilots had no open-ocean navigation experience, two of the enlisted aircrew on the VT-8 aircraft were replaced by two officer navigators from Patrol Squadron 24 (VP-24), Ensign Jack Winton Wilke and Ensign Joseph Metcalf Hissem.

The six TBFs took off from Luke Field, Pearl Harbor, at 0700 on Monday, 1 June, and after an eight-hour flight landed at the airfield on Eastern Island, Midway, without incident.

That same day, four U.S. Army Air Forces (USAAF) B-26 Marauder twin-engine bombers arrived on Midway Island, commanded by Captain James J. “Jim” Collins. The B-26s were from two different bomb groups that were destined for Australia. Collins and his crew and one other aircrew were from the 69th Bomb Squadron, 38th Bomb Group, flying the B-26B. The other two aircraft were from the 18th Reconnaissance Squadron of the 22nd Bomb Group, which were re-subordinated to the 22nd Bomb Squadron of the 408th Bomb Group just before the mission. The planes had arrived in Oahu aboard ship about 10 days earlier (although Collins had been awarded a Distinguished Service Cross for flying a B-26 to Oahu from the West Coast). While in Hawaii, the planes were modified to carry a Mk. XIII torpedo, and spent several days practicing torpedo runs without actually dropping a torpedo. None of the crews had any combat experience.

On 2 June, the Marine air group commander on Midway, Lieutenant Colonel Ira Kimes, briefed the new arrivals on the basic concept of operations for the anticipated Japanese attack. Upon warning of an incoming Japanese air raid, Midway would launch everything that could fly (that wasn’t already in the air) to avoid planes being destroyed on the ground. All the Marine fighters (mostly obsolete F2A Buffalos and a few F4F Wildcats) would intercept the Japanese raid and defend the island. The USAAF B-17s would probably already be in the air, and would be directed to the targets accordingly. The TBFs and B-26s were to launch and loiter to rendezvous with the Marine dive-bombers (16 SBD Dauntlesses and 11 obsolete SB2U-3 Vindicators), and if there was locating information on the Japanese force, would then proceed to conduct a coordinated attack against the Japanese without fighter escort.

Fieberling argued against the plan, as without fighter escort, it negated the TBF’s primary defensive advantage, which was speed. Also, by the time the gaggle was formed up, the Japanese would likely be many miles from the reported position and none of these groups had ever practiced a coordinated attack with each other. It would become apparent that Captain Collins didn’t like the plan either.

Some accounts indicate that the commander of VT-8, Lieutenant Commander Waldron, embarked on Hornet, did not know that a detachment of his squadron had arrived in Hawaii. However, the VT-8 War Diary indicates Waldron was aware that as of 3 June, the detachment under Fieberling had arrived on the island. The converse was not true, as the location of the carriers was a tightly held secret, so probably no one on the island knew where the carriers were, and only a handful outside the carrier task forces knew either.

On 3 June, nine B-17Es from Midway bombed the Japanese invasion force (separate from the still undetected carrier strike force) at long range west of Midway without any hits. During the night of 3–4 June, a radar-equipped PBY-5A Catalina flying boat successfully hit the Japanese tanker Akebono Maru with a torpedo that damaged the ship and killed 23 sailors. However, but the ship continued on with the task force. This was the first torpedo attack by a PBY, and would turn out to be the only torpedo that hit and exploded on target during the entire battle.

At 0350 on 4 June 1942, the B-17s on Midway began warming up for another attack on the Japanese invasion force. Fifteen bombers were away by 0415, as were 22 Catalinas, with the PBYs concentrating the search to the northwest of Midway in anticipation of the imminent arrival of the Japanese carrier force—per the intelligence estimates (see H-Gram 006/H-006-2).

At about 0530, a PBY sighted the Japanese force northwest of Midway within a few miles and minutes of the intelligence estimate time and location. It was a few more minutes before another PBY sighted many Japanese aircraft heading toward Midway. Several more minutes would pass before a PBY reported sighting two Japanese carriers (out of the four in the carrier strike force). None of this detail was known to the TBF crews, who had already manned their aircraft before dawn in anticipation.

At 0555, a truck with Marines drove down the flight line with the word to launch all aircraft and that the enemy location was bearing 320 degrees true and 150 nautical miles from Midway. The TBFs immediately began to taxi to follow the Marine fighters. Six F4F Wildcats and 18 F2A Buffalos of Marine Fighter Squadron VMF-111 would attempt to defend the island.

Of the 18 personnel aboard the TBFs, 15 were from VT-8, plus the two navigators from VP-24. Aviation Ordnanceman Third Class Lyonal J. Orgeron, from PBY squadron VP-44 at Midway, replaced Aviation Machinist’s Mate First Class William Coffey of VT-8 on one of the aircraft. Lieutenant Fieberling decided that Coffey’s particular expertise with the new TBF engine was too valuable to risk, and he was swapped out with Orgeron at the last moment (this would result in an administrative embarrassment when Coffey’s parents were informed he was missing in action). With Fieberling were Ensign Wilke of VP-24 and Radioman Second Class Arthur R. Osborn. None of the personnel in this group of six aircraft had combat experience or had ever launched a live torpedo.

Fieberling never told his squadron what he intended to do after take-off, but it quickly became apparent he was not going to wait around for the 16 SBDs and 11 obsolete SB2U-3s. He had a reputation in the squadron as an extremely capable pilot and leader—cool, calm, and always caring for his men. Like his role model, skipper John Waldron, Fieberling was described as the kind of leader others would willingly follow into hell, and that’s exactly what they did. Fieberling headed at 320 degrees true, toward the Japanese contact, and never deviated. This would be the first combat mission for the TBF aircraft and for all of those aboard.

The TBF formation flew at 4,000 feet and at a speed 160 knots, through scattered clouds with otherwise good visibility. Fieberling led the formation with Earnest on his left wing and Brannon on his right. Gaynier led the second echelon behind and to the right of Fieberling, with Lewis and Woodside on his wings.

As the TBFs left the Midway area, they could see flaming planes from the air battle between the Midway Marine fighters and Japanese escort fighters of the 108-plane Japanese raid. The Japanese were expecting to catch Midway by surprise, but instead were surprised when they were jumped by the Marine fighters at about 0620, 30 miles from the atoll. Three Japanese Kate torpedo bombers (being used in a horizontal bombing role) and one or two Zero fighters were shot down before the Japanese turned the tables on the Marines, shooting down two Wildcats and 13 Buffaloes. The surviving Marine fighters were so shot up that only two fighters based on Midway were ultimately still in flyable condition.

The Japanese then got their second shock by the intensity of anti-aircraft fire from Marine guns on the island that were ready and waiting. As a result of the raid, the Japanese lost a total of 11 aircraft shot down or forced to ditch on the way back to their carriers. A further 14 Japanese aircraft were so badly damaged they were not available for further operations, and another 29 were damaged to some degree. The torpedo-bomber squadron on Hiryu was particularly hard hit, with only eight Kate torpedo planes still operational. These would later cripple Yorktown with two torpedoes, so every loss mattered (see H-Gram 006/H-006-4).

As the Japanese raid on Midway was inbound, two Japanese fighters approached the TBF formation, but opted not to seriously engage. Oddly, these planes were reported as “Messerschmitts” in keeping with a still prevalent mindset that the Japanese had to be getting technological help from a Western nation like Germany. The only planes in the Japanese carrier force that looked remotely like a Messerschmitt were the two D4Y1 experimental Type 13 carrier dive-bombers, configured as high-speed reconnaissance aircraft, embarked on Soryu. However, one D4Y1 wasn’t launched until 0820. (Later production models were known as “Judy.”)

The four B-26s launched from Midway right after the six TBFs, flying in a diamond formation with Collins in the lead. Behind and to the right of Collins was a B-26B flown by First Lieutenant William S. Watson, and to the left was B-26A “Satan’s Playmate,” flown by First Lieutenant Herbert C. Mayes. In the rear was B-26 “Susie-Q,” flown by First Lieutenant James P. Muri. Each B-26 had a crew of seven. Collins made the same decision as Fieberling: to proceed directly to the Japanese contact position without waiting to form up with the Marine dive-bombers. Collins didn’t tell his crew they were going on a strike mission. The B-26s were faster than the TBFs and would sight the Japanese at about the same time as the VT-8 detachment. (Apparently only the 18th Reconnaissance Squadron’s B-26s had names and nose art).

Burning oil tanks on Sand Island, Midway, following the Japanese air attack delivered on the morning of 4 June 1942. These tanks were located near what was then the southern shore of Sand Island. This view looks inland from the vicinity of the beach. Three Laysan albatross (gooney bird) chicks are visible in the foreground (80-G-17056).

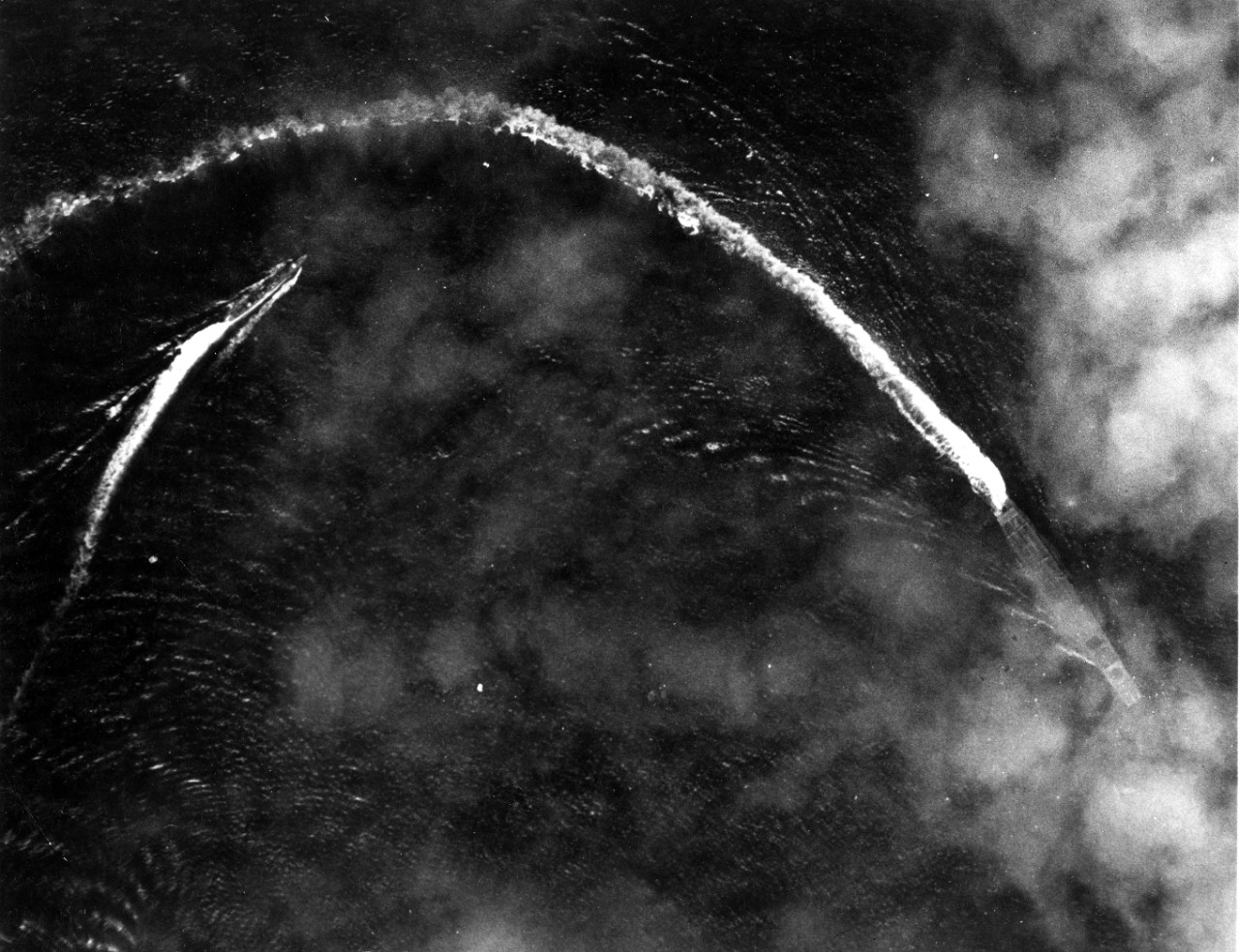

At 0655, the TBFs sighted the Japanese carrier force. The B-26s coming up to the left (southwest) of the TBFs sighted the Japanese about the same time. Although the U.S. aircraft probably never saw more than three carriers, the four carriers were operating in a rough box heading southeasterly into the wind. Hiryu was on the right (east side) while the flagship Akagi was on the left (southwest) side. Behind the lead carriers were Soryu to the north and Kaga to the northwest. Steaming ahead of the carriers was battleship Haruna to the east, light cruiser Nagara in the center, and heavy cruiser Tone to the west. Behind the carriers were battleship Kirishima and heavy cruiser Chikuma. In keeping with Japanese doctrine, the escort ships were at a good distance from the carriers to provide early visual warning (since none had radar) and to give the carriers plenty of sea room for radical evasive maneuvering, which the Japanese viewed as the most effective defense.

There is no indication either the TBFs or the B-26s knew where the other group was, but they commenced their attack runs at about the same time. The TBFs went for the carrier on their right, Hiryu, and the B-26s for the carrier on their left, Akagi.

At 0700, the commander of the Japanese carrier strike force (the Kido Butai) Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo, on Akagi, received the code word message “Kawa Kawa Kawa” from the leader of the Midway strike, Lieutenant Joichi Tomonaga. The message meant that a second strike on Midway would be necessary (this transmission was intercepted by U.S. radio intelligence). In keeping with Japanese doctrine, and orders from the commander-in-chief of the Combined Fleet, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, Nagumo had about half his aircraft in reserve (107 total) in case any U.S. carriers showed up, which so far had not been spotted by the Japanese. The Japanese torpedo planes on Akagi and Kaga were already uploaded with torpedoes, which was done in the hangar bays. The torpedo planes on Hiryu and Soryu had been used on the Midway strike as horizontal bombers; they would have to be recovered first. Because the Japanese loaded dive-bombers on the flight deck, the dive-bombers on Hiryu and Soryu were still struck below, awaiting the return of the Midway strike.

Since no U.S. ships had been spotted yet, there was no reason to launch the reserve strike, which, due to timing, would have to wait until the Midway strike recovered. Nagumo and has staff fully expected that a second strike on Midway would be needed, so the code word message from Tomonaga came as no big surprise, although none of them knew at that point just how badly the strike had been shot up. The second strike would require that bombs be substituted for torpedoes on the torpedo bombers, and general-purpose bombs be substituted for armor-piercing bombs (which actually weren’t loaded yet).

At 0710, eagle-eyed lookouts on Akagi sighted the incoming TBFs and then the B-26s at about the same time as the escorts on the periphery. Under Japanese doctrine, the ships on the periphery would fire their main battery to alert the rest of the force that a raid was inbound, as well as signaling the general direction. Because few Japanese aircraft had radios, and on those that did the radios were not very reliable, the main battery fire from the escorts was often the only way that the fighters on combat air patrol (CAP) knew where to head for an intercept.

At the time the U.S. raid was spotted, the Japanese had about 30 fighters already in the air or just in the process of launching. It would take time for many of these to get into the fight, so initially the TBFs were intercepted by about six Japanese fighters and the B-26s by about the same number, with more fighters piling on as the fight developed.

The Japanese carrier pilots were in for a rude shock, as none of them had seen either type of aircraft before (B-26s had flown several combat missions around New Guinea by this time, but were unknown to the carrier pilots). Both types of aircraft were very resistant to battle damage (unlike Japanese aircraft, which tended to turn into flaming torches when hit). The Japanese Zeros filled the TBFs and B-26s full of 7.7-millimeter machine-gun holes that appeared to have little effect. This forced the Zeroes to use their 20-millimeter cannon, which required them to steady up on the target for longer and made them more vulnerable to defensive fire.

To the consternation of the Japanese, the first planes to go down were not American, but one Zero flamed by a TBF and another by a B-26. The result was a breakdown in discipline among the Japanese as so many jockeyed for position to avenge their downed comrades that they literally cut each each other off.

As the fighter attack intensified, Fieberling led his planes down in a full-throttle dive, reaching speeds of 300 knots, from 4,000 down to 200 feet. When they reached the bottom of the dive, Ensign Earnest on the far left of the formation was able to see that all aircraft were still in formation, although his plane had already taken a massive beating as had probably most of the others.

Although the TBF was faster than the TBD and had the capability to drop from higher altitude, its survivability was still impacted by the slow speed and low altitude required to drop the Mk. XIII torpedo without damaging the torpedo’s guidance and arming systems. As the TBFs slowed, they became more vulnerable. (After the battle, the Bureau of Ordnance was compelled to conduct serious testing on live torpedoes. It was discovered that the low-speed “belly flop” mode of delivery was actually counter-productive; the torpedo performed better when released with a higher-altitude, higher- speed “nose dive” delivery. Many torpedo-bomber crews might have survived had this been discovered sooner.)

By this time, Earnest’s forward-firing .30-caliber machine gun had failed. He could not communicate with his gunners, because the turret gunner, Aviation Machinist’s Mate Third Class Jay D. Manning, had taken a 20-millimeter round square in the chest, blowing him to bits and flooding the lower radio compartment with blood. Earnest’s radioman, Radioman Third Class Harry H. Ferrier, was shortly knocked unconscious by a round that creased his forehead. Earnest was wounded in the neck, but figured if it was serious he’d be dead. The instrument panel was smashed along with the compass, elevator control severed, and hydraulic system shot out. Earnest struggled to control the aircraft, but when it appeared apparent he was going to hit the water, he veered from formation, noting the other five aircraft still pressing ahead, and he launched his torpedo at the light cruiser Nagara. Earnest was uncertain if the torpedo dropped, even after he pulled the emergency release handle. It had, but Nagara was able to avoid it.

When Earnest’s TBF was down to about 20 feet above the water, and he was sure he was going to crash, he somewhat inadvertently discovered he had a minimum level of control using the elevator trim tab. Once clear of Nagara’s anti-aircraft fire, more Zeroes jumped Earnest and shot more holes in the plane. The TBF just refused to go down and the Zeroes finally gave up as Earnest limped off in a northwesterly direction (the opposite of the way back to Midway).

Crew of U.S. Army Air Forces First Lieutenant James Muri's B-26, who made a torpedo attack on a Japanese aircraft carrier during the early morning of 4 June 1942. The plane had more than 500 bullet holes when it landed at Midway following this action. Muri is second from left, in the front row (USAF-22850-AC).

As the TBFs and B-26s passed the outer escorts, the fighter attacks let up momentarily as the fighters avoided the anti-aircraft fire from their own ships. However, five TBFs and all four B-26s were still boring in on the Japanese carriers despite the intense but ineffective anti-aircraft fire. By this time, both Hiryu and Akagi had turned to port to unmask their starboard batteries as the planes kept on coming. In increasing desperation, Japanese fighter pilots braved the fire from their own ships to press home attacks.

By this time, most of the gunners on the TBFs were probably dead or dying as Japanese fighters poured fire into the stubborn American torpedo bombers. Finally, the cumulative damage was too much and the TBFs started to go down one after the other. The B-26 on the right, flown by First Lieutenant Watson, took a direct hit from something that caused it to explode in flight and crash, with the loss of all seven aboard.

No doubt realizing that there would be no escape, two surviving TBFs nevertheless pressed their attack on Hiryu close enough to launch their torpedoes before they each crashed. Although within range, Hiryu had enough time and room to turn away and outrun the torpedoes (Hiryu’s top speed was about the same as that of a Mk. XIII torpedo).

Three riddled B-26s pressed their attack on Akagi. Collins’ forward-firing guns malfunctioned, but he was able to loose a torpedo at 200 feet altitude and 800 yards from Akagi. Collins passed over the bow of the carrier at about 100 feet before executing a 1,000-foot zoom climb and escaping with 189 holes in his aircraft. First Lieutenant Muri’s “Susie-Q” dropped its torpedo at 800 yards, but Akagi was able to avoid his and Collins’ torpedoes. Under heavy fire, Muri decided the safest place was right above Akagi as he sped across the carrier’s flight deck at bridge height from bow to stern, strafing the flight deck and killing two Japanese sailors in the forward-most 25-millimeter gun on the port side.

As “Susie-Q” buzzed Akagi’s flight deck, Muri saw another B-26 pass right overhead. This was “Satan’s Playmate,” flown by First Lieutenant Mayes. Whether “Satan’s Playmate” launched a torpedo is unknown; if it did, the torpedo missed or failed to detonate. From the Japanese perspective, it looked as if the B-26 was heading unerringly for Akagi’s bridge. In Japanese accounts, those on the bridge thought the plane couldn’t miss and they were all going to die. At the last instant, “Satan’s Playmate” missed Akagi’s bridge by a few feet, sparing Vice Admiral Nagumo and his staff, before cartwheeling into the sea on the opposite side with the loss of all seven aboard.

Both Collins and Muri made it back to Midway, crash-landing their aircraft. Neither B-26 ever flew again. Muri’s plane had over 500 holes. This was the first and last torpedo attack mission ever flown by the U.S. Army Air Forces or U.S. Air Force. Whether Mayes’ damaged plane was out of control or on a suicide run will never be known. What is known is that the attacks by the TBFs and B-26s had a profound effect on the Japanese.

By 0715, the torpedo attack was over. Out of 10 aircraft, seven were shot down with no hits. It would go down in the history books as a “failed” and futile attack. (The 1976 movie Midway omits it completely. The 2018 movie omits the TBF attack, and grossly mischaracterizes the B-26 attack—two of my biggest complaints about an otherwise more accurate movie than the 1976 version.) In actuality, this attack was a pivotal moment in the battle.

Vice Admiral Nagumo had a reputation (mostly unjustified) for being indecisive, but at this moment he was the exact opposite: at 0716, he ordered his reserve strike to be re-armed for another attack on Midway Island, a decision that would probably be the most second-guessed in the entire history of naval warfare. Nagumo did not yet know how extensive the losses and damage were to his first strike (nor did he know how badly damaged Midway was). However, he did know that these 10 planes came from Midway, and despite overwhelming odds, not one of them turned away, penetrating through a screen of 30 fighters and an intense shipboard anti-aircraft fire to get four torpedoes dangerously close to two of his carriers. The TBFs and B-26s showed the kind of samurai bravery that impressed the Japanese, partly because it was so shockingly unexpected. At this point, there was still no sign of any U.S. carriers, and Midway apparently still presented a threat that needed to be respected.

What Nagumo did not know was that the American carriers knew where he was, and by 0714 both Enterprise and Hornet were launching aircraft to strike the Japanese carriers. At 0734, the 15 Devastators of VT-8 commenced launching from Hornet, led by skipper Waldron.

At 0740, Nagumo received the first report from a scout aircraft locating U.S. ships northeast of Midway. Far from being indecisive, Nagumo immediately recognized the grave threat, as there was no reason for U.S. ships to be there without an aircraft carrier, even though—based on Japanese intelligence reporting—if there was a U.S. carrier, there couldn’t be more than one. At 0745, Nagumo quickly ordered a halt to the re-arming of the reserve strike, and ordered the anti-ship weapons reloaded. He was in no position to launch anything yet, otherwise the strike returning from Midway would run out of gas, and half his aircraft would be forced to ditch.

As the TBF/B-26 attack on the Japanese carriers was ongoing around 0710, the submarine USS Nautilus (SS-168) sighted smoke from bombing and AA fire beyond the horizon to the northwest. The commanding officer of Nautilus, Lieutenant Commander William Brockman, ordered the crew to battle stations and immediately altered course to investigate the sighting. At 0755, Brockman sighted the masts of the Japanese force and continued to close. At the same time, a Japanese Zero sighted and strafed his periscope and forced Nautilus back down. At 0800, Brockman tried again as he sighted a battleship and three light cruisers (misidentifying all of them).

Brockman attempted to engage the battleship (Kirishima), but was promptly bombed by a Japanese floatplane that narrowly missed, while the light cruiser Nagara and two destroyers commenced a run at the submarine. Brockman boldly remained at periscope depth, but just as Nautilus was set up for a shot, Nagara dropped five depth charges at 0810, followed by another six at 0817. Nautilus went back down to 90 feet, followed by nine more depth charges.

It took over 45 minutes for the Marine dive-bombers from Midway to form up and push to attack the Japanese carriers. At 0800, as Nautilus was being hammered by depth charges, 16 SBD Dauntless dive-bombers of VMSB-241, under the command of Major Lofton Henderson (whose name would be immortalized at Henderson Field on Guadalcanal) commenced an attack on carrier Hiryu. Due to the inexperience of his pilots, Henderson opted to conduct a glide-bomb attack rather than dive-bomb. Eight of the SB’s were shot down by Japanese fighters (including Henderson), while achieving multiple near-misses but no hits on Hiryu. This furthered Nagumo’s resolve to finish off the threat from Midway. The 11 slow Vindicators arrived about 20 minutes later, but due to the intensity of opposition opted to bomb the battleship Haruna rather than penetrating all the way to the carriers; no hits were achieved but most of the obsolete aircraft survived (three were lost).

At 0824, a periscope popped up in the middle of the Japanese formation. It was Nautilus again trying to get a shot at the battleship. The battleship fired a full starboard broadside at the periscope (although this may actually have been a warning of the incoming Vindicator air attack). One of Brockman’s torpedoes was running hot in the tube making a terrific noise as Nagara and the destroyers closed in again. Still, Brockman pressed home the attack, firing two torpedoes at Kirishima at a range of 4,500 yards. One torpedo never left the tube and Kirishima dodged the other. Nagara forced Nautilus down to 150 feet for another depth-charge pounding.

At 0835, Ensign Earnest was still flying the severely damaged TBF on a circuitous path to the west of the Japanese force and, with all his instruments shot away, using only his watch to guess when to head east toward Midway, knowing if he was too far north or south he would miss it and vanish into the Pacific. The good news was that his wounded radioman Ferrier regained consciousness, although the radio was useless. Fortunately for Earnest, the towering pillar of black smoke from the burning fuel farm at Midway could be seen from many miles away.

At 0846, Nautilus tried again and was forced back down again by Nagara. At 0900, Brockman put his periscope up, this time sighting a Japanese carrier for the first time. Again, Nagara spoiled the approach, so Brockman fired a torpedo at the persistent cruiser at 2,600 yards, but she jinked and the torpedo missed. Nautilus was forced deep yet again as she was pounded by 14 depth charges over the next 30 minutes.

Whether by order or by initiative, the destroyer Arashi remained behind to keep Nautilus pinned down while the carrier force moved away. Nautilus went down to 200 feet trying to shake the Arashi, but without success. Finally, at 0933, the destroyer dropped her last two depth charges, which were the closest of any, severely jarring Nautilus. Arashi then picked up speed to catch up with the Japanese carrier force.

At 0908, the 15 TBDs of VT-8 were approaching the Japanese carrier force, with no fighter cover and separated from the rest of the Hornet strike package (which missed the Japanese entirely). Before launching, skipper Waldron had told his squadron that if only one plane was left, he wanted that plane to go in and get a hit. Showing the same level of courage as the Midway VT-8 detachment, the TBDs from Hornet pressed their attack against overwhelming odds, not one turning away, but all but one were shot down by Japanese fighters before launching a torpedo. One TBD flown by Ensign George Gay got close enough to launch a torpedo at carrier Soryu, which Soryu out-maneuvered, before Gay’s plane was jumped by five more Zeros and shot down. Gay would be the only survivor from among the VT-8 TBD aircrews.

At about 0944, Earnest would make a successful one-wheel crash landing at Midway (only then knowing for certain his torpedo was gone). Earnest’s plane, BuNo 00830, was actually the first one off the Grumman production line; the battered aircraft was shipped back to Pearl Harbor for study. It had survived being hit by at least 64 7.7-millimeter machine-gun rounds and nine 20-millimeter cannon shells. Of the 21 aircraft and 48 aircrewmen involved in the two VT-8 attacks on 4 June 1942, 20 aircraft were shot down and 45 men were killed.

At 0955, Lieutenant Commander Wade McClusky was leading a strike of 33 (initially) SBD Dauntless dive-bombers. Having actually overshot the Japanese carrier force without seeing it, McClusky’s strike was already past critical fuel state. He would have to turn around and head back to the carrier, knowing some of his aircraft were so low on fuel they wouldn’t make it, or turn in the opposite direction and try to reach Midway Island. Just at this critical decision point, McClusky sighted a lone “cruiser” hightailing it to the northeast. The “cruiser” was actually the destroyer Arashi trying to catch up with Nagumo’s carrier force after holding down Nautilus. McClusky correctly deduced that a lone ship at high speed would be heading toward the main force, not away from it. McClusky turned to head in the same direction as Arashi.

At 1000, McClusky sighted the wakes of the Japanese carrier force. By 1020, his dive-bombers arrived over the Japanese carriers Akagi and Kaga, by sheer luck as 17 dive-bombers from Yorktown arrived over Soryu. This occurred at the same time as the Japanese fighters were down low, shooting down 10 of 12 of Yorktown’s torpedo-bomber squadron (VT-3) after having done much the same to Enterprise’s VT-6. Other Japanese fighters were preoccupied with the Yorktown strike’s fighter escort. As a result, three squadrons of U.S. dive-bombers arrived over the Japanese carriers unseen and unopposed. Within less than ten minutes, Akagi, Kaga, and Soryu were mortally wounded and out of action. All three would later be scuttled. (Nautilus finally hit the burning and drifting Kaga with a torpedo, which failed to explode.)

The “failed” attack led by Lieutenant Fieberling led Nautilus to the Japanese carriers, led destroyer Arashi to keep Nautilus under, and Arashi unknowingly led McClusky’s dive-bombers to one of the most decisive victories in the history of naval warfare. If there was a “miracle” at Midway, it was this sequence of events—and Lieutenant “Old Langdon” Fieberling started it.

The heroes of VT-8 Midway Detachment by aircraft (side number)

- 8-T-16: LT Langdon K. Fieberling, ENS Jack Wilke, RM2c A. R. Osborn

- 8-T-19: ENS Charles E. Brannon, AMM3c W. C. Lawe, AOM3c C. E. Fair

- 8-T-1: ENS Albert K. Earnest, ARM3c H.H. Ferrier, AMM3c J.D. Manning

- 8-T-12: ENS Victor A. Lewis, AMM3c N. L. Carr, EM3c J. W. Mehltretter

- 8-T-4: ENS Oswald J. Gaynier, ENS Joseph M. Hissem, SEA1c H.W. Pitt

- 8-T-5: NAP Darrell D. Woodside, PTR2c A. T. Meuer, AOM3c L. J. Orgeron.

Fieberling, Brannon, Lewis, Gaynier, and Woodside of VT-8 were all awarded the Navy Cross, posthumously. Wilke and Hissem of VP-24 were awarded the Navy Cross, posthumously. Earnest was awarded two Navy Crosses, one for the torpedo attack, and the second for his epic return flight. Osborn, Lawe, Fair, Manning, Carr, Mehltretter, Pitt, and Meuer of VT-8 were awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, posthumously. Orgeron of VP-44 was awarded the Distingished Flying Cross, posthumously. Ferrier of VT-8, the only enlisted survivor of the two VT-8 strikes on 4 June 1942, was awarded a Distinguished Flying Cross.

The following ships were named after the VT-8 Midway detachment:

- Buckley-class destroyer escort USS Fieberling (DE-640) was commissioned in April 1944, earned one Battle Star at Okinawa, where she was lightly damaged by a kamikaze near miss. Decommissioned in March 1948.

- John C. Butler–class USS Charles E. Brannon (DE-446) was commissioned in November 1944, earned one Battle Star in Borneo campaign. Decommissioned in May 1946.

- John C. Butler–class destroyer escort USS Lewis (DE-535) was commissioned in December 1943 and earned three Battle Stars. Decommissioned in May 1946. Recommissioned in March 1952, earned one Battle Star in Korean War and was the support ship for deepest ocean dive by Trieste. Decommissioned in May 1960.

- Canon-class destroyer escort USS Gaynier (DE-751), cancelled while under construction in September 1944 and scrapped on ways.

- Canon-class destroyer escort USS Jack W. Wilke (DE-800) was commissioned in March 1944 and conducted Atlantic convoy and ASW operations. Decommissioned in May 1960.

- Edsall-class destroyer escort USS Hissem (DE-400) was commissioned in January 1944, earned one Battle Star in German air attacks against Mediterranean convoys. Served in Vietnam War, decommissioned in May 1970.

The entire crews of all four USAAF B-26 bombers were awarded the Distinguished Service Cross (Army equivalent of the Navy Cross).

VT-8 would be reconstituted after the Battle of Midway with the TBFs still at Pearl Harbor, and under the command of Lieutenant Swede Larson. VT-8 would re-embark on Hornet for action around Guadalcanal until Hornet was sunk at the Battle of Santa Cruz in October 1942. The remainder of the squadron then operated from Henderson Field in austere conditions. Seven more pilots and aircrewmen were killed and eight wounded in this second incarnation of VT-8. Bert Earnest would earn a third Navy Cross for actions against the Japanese around Guadalcanal in September and October 1942. On 13 November 1942, in one of the last acts of the squadron, Swede Larson put a torpedo into the drifting Japanese battleship Hiei, which had been crippled during the night of 12/13 November, hastening the sinking of the vessel. By late 1942, the pilots and aircrew were so debilitated by jungle disease and exhaustion that the squadron was decommissioned. (See H-Grams 010, 011, and 012 for the Guadalcanal battles.)

During the life of the squadron, 35 pilots in VT-8 would earn 39 Navy Crosses. Enlisted aircrewmen would earn over 50 medals for valor. The squadron was the only unit to be awarded two Presidential Unit Citations during World War II, one for Midway and the other for Guadalcanal.

Selected Award Citations

The President of the United States of America takes pride in presenting the Navy Cross (Posthumously) to Lieutenant Langdon Kellogg Fieberling, United States Naval Reserve, for extraordinary heroism in operations against the enemy while serving as a Pilot of a carrier-based Navy Torpedo Plane and Flight Leader in Torpedo Squadron EIGHT (VT-8), embarked from Naval Air Station Midway during the “Air Battle of Midway,” against enemy Japanese forces on 4 June 1942. In the first attack against an enemy carrier of the Japanese invasion fleet, Lieutenant Fieberling led his flight in the face of withering fire from enemy Japanese fighters and anti-aircraft forces. Because of the events attendant upon the Battle of Midway, there can be no doubt that he gallantly gave up his life in the service of his country. His courage and utter disregard for his own personal safety were in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service. He gallantly gave his life for his country.

***

The President of the United States takes pleasure in presenting the Navy Cross to Ensign Albert Kyle Earnest, United States Naval Reserve, for extraordinary heroism in operations against the enemy while serving as a Pilot of a carrier-based Navy Torpedo Plane of Torpedo Squadron EIGHT (VT-8), embarked from Naval Air Station Midway during the “Air Battle of Midway,” against enemy Japanese forces on 4 June 1942. In the first attack against an enemy carrier of the Japanese invasion fleet, Ensign Earnest pressed home his attack in the face of withering fire from enemy Japanese fighters and anti-aircraft forces. His loyal devotion to duty and utter disregard for his own personal safety in attacking a superior enemy force were in keeping with the highest tradition of the United States Naval Service.

***

The President of the United States takes pleasure in presenting a Gold Star in lieu if a Second Award of the Navy Cross to Ensign Albert Kyle Earnest, United States Naval Reserve, for extraordinary heroism in operations against the enemy while serving as a Pilot of a carrier-based Navy Torpedo Plane of Torpedo Squadron EIGHT (VT-8), embarked from Naval Air Station Midway during the “Air Battle of Midway,” against enemy Japanese forces on 4 June 1942. Having completed an unsupported torpedo attack in the face of tremendous enemy fighter and anti-aircraft opposition, Ensign Earnest, himself wounded and his gunner dead, made his return flight in a plane riddled by machine gun bullets and cannon shell. With his compass and bomb bay doors inoperative, one wheel of his landing gear unable to be extended and his elevator control shot away, he was forced to fly by expert use of his elevator trimming tabs some 200 miles back to Midway where he negotiated a safe one-wheel landing. Fully aware of the inestimable importance of determining the combat efficiency of a heretofore unproven plane, Ensign Earnest doggedly persisted in spite of tremendous hazards and physical difficulties. His great courage and marked skill in handling his crippled plane were in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.

____________

Sources include: A Dawn Like Thunder: The True Story of Torpedo Eight, by Robert J. Mrazek, Little, Brown and Co., 2008; The Unknown Battle of Midway: The Destruction of the American Torpedo Squadrons, by Alvin Kernan, Yale University Press, 2005; Shattered Sword: The Untold Story of the Battle of Midway, by Jonathan Parshall and Anthony Tully, Potomac Books, 2005; The First Team: Pacific Naval Air Combat from Pearl Harbor to Midway, by John B. Lundstrom: Naval Institute Press, 2005; No Right to Win: A Continuing Dialogue with Veterans of the Battle of Midway, by Ronald W. Russell, iUniverse, Inc., 2006; Searching for the Truth: The Battle of Midway, by George J. Walsh, CreateSpace, 2015; Midway 1942: Turning Point in the Pacific, by Mark Still,: Osprey Publishing, 2010; TBD Devastator Units of the U.S. Navy, by Barrett Tillman, Osprey Publishing, 2000; Victory at Midway: The Battle that Changed the Course of World War II, by James M. D’Angelo, McFarland and Co. Publishers, 2018; Midway: The Battle that Doomed Japan, by Mitsuo Fuchida and Masatake Okumiya, United States Naval Institute, 1955; “Fieberling” at militaryhallofhonor.com; NHHC Dictionary of American Fighting Ships (DANFS); combinedfleet.com for Japanese ships.