H-063-2: The Battle of Somatti, Fiji, 1859

In the summer of 1859, two American merchant sailors were killed and eaten by tribesmen on the island of Waya in the Fiji Islands. When the American Consul on Ovalau, Fiji, learned of the incident, he requested that the sloop-of-war USS Vandalia, recently arrived from Panama, launch a punitive expedition against the offending Wayan tribe.

Fiji had a long-standing reputation for being dangerous to outsiders, and there were a number of recorded incidents of shipwrecked sailors being killed. During the first official U.S. Navy visit to Fiji in 1840 by Lieutenant Charles Wilkes’s U.S. Exploring Expedition, natives had killed and mutilated Lieutenant Joseph Underwood and Midshipman Henry Wilkes (Wilkes’s nephew). In retaliation, Wilkes landed about 60 Marines and sailors, torched two villages and killed about 80 Fijian natives (see H-Gram 062).

Trouble in Fiji flared again in 1849 when the house owned by U.S. agent John Brown Williams was hit by cannon fire from natives reportedly celebrating U.S. Independence Day. By 1855, civil war had broken out on the islands, and Williams’ house and store were burned and looted, as were other American-owned property. At that time, one of the stronger chiefs in Fiji, Seru Epenisa Cakabou, the Vunivalu of Bau, had proclaimed himself Tui Viti (King of Fiji). Not all the chiefs were inclined to go along, resulting in numerous fights and murders in the islands.

In October 1855, the veteran frigate USS John Adams arrived to monitor the situation on behalf of the United States. John Adams was under the command of Commander Edward B. Boutwell. Boutwell put parties ashore several times to monitor events and to provide some order. After learning about the burning of Williams’ store, Boutwell demanded $5,000 dollars in compensation from Chief Cakabou. This demand escalated to $45,000 dollars as additional reports of property damage were received. This put Cakabou in a touchy no-win situation. The U.S. demand for compensation from him was a tacit recognition of him being the King of Fiji, which he sought. However, if he refused (or could not) pay, that would jeopardize his legitimacy in the eyes of some chiefs. On the other hand, other chiefs would view him as weak for capitulating to U.S. demands. Regardless, Cakabou missed Boutwell’s deadline to pay. A short battle followed in which U.S. Marines routed Fijian warriors at a cost of one American killed in action and two wounded. However, Cakabou escaped into the interior. At this point, the situation in Fiji settled down for several years.

Things came to a head in Fiji again in 1859 in conflict between tribes that were friendly to Western trade and those that were hostile. (The situation was actually far more complex than I care to get into.) The hostile tribes were known to kill, and cannibalize, members of the friendly tribes. In 1859, tribesmen from the village of Somatti on Waya Island expanded their menu and ate a couple of Americans.

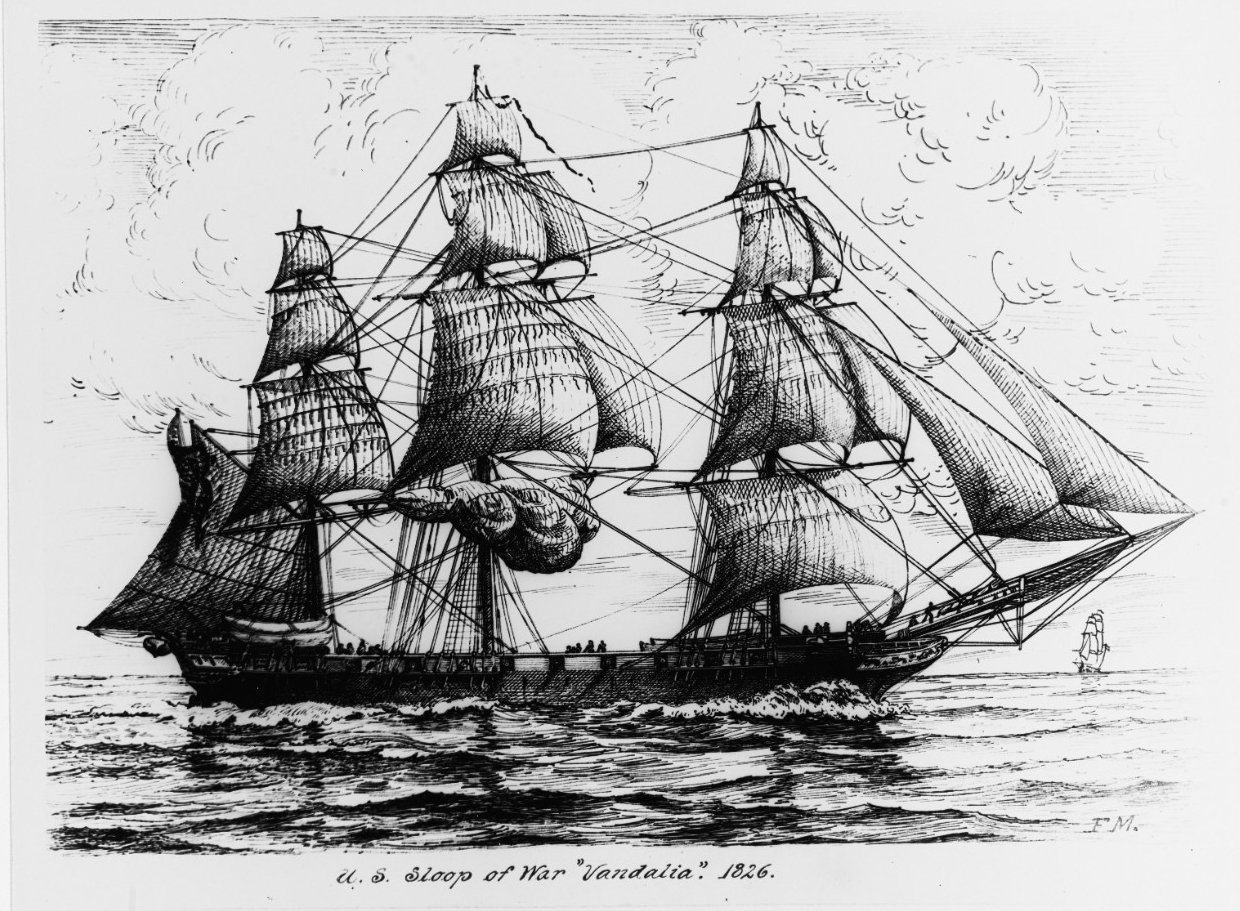

Vandalia arrived in Fiji on 2 October 1859. Vandalia was an 18-gun sloop-of-war, commissioned in 1825, with a crew of about 150, armed with four 8-inch shell guns and 16 32-pounder broadside guns. Vandalia had served in the Brazil Squadron (1828–31) and the West Indies Squadron (1832–1839). She cooperated with U.S. Army forces during the Second Seminole War (1835–45). She then served in the Home Squadron until she suffered a Yellow Fever outbreak in 1845 and was laid up until 1849 (missing the Mexican-American War). It was not until the 1880s that it was understood that mosquitoes were the vector for Yellow Fever. When a ship suffered an outbreak, the standard solution was to decommission it for several years. Vandalia joined the Pacific Squadron in 1849 and then the East Indies Squadron in 1853. While with the East Indies Squadron, Vandalia was part of Commodore Mathew Perry’s second visit to Japan and served to protect U.S. interests in China during the Taiping Rebellion. She rejoined the Pacific Squadron in 1857.

Under the command of Commander Arthur Sinclair, Vandalia stopped at Nuku Hiva in the Marquesas Islands on 5 August 1858, en route to Tahiti from Panama. While there, a small boat arrived with the captain, first mate, and two others of the U.S.-flag clipper ship Wild Wave. The clipper had wrecked on remote uninhabited Oeno Island on 4 March 1858 while sailing from San Francisco to Valparaíso, Chile. Captain Josiah Knowles and six of his crew set sail in the ship’s boat to seek help, leaving 33 crewmen and passengers, plus Knowles’ wife, marooned on Oeno Island. Knowles’ boat had been wrecked on Pitcairn Island (of Mutiny on the Bounty fame). The entire population of Pitcairn Island had moved to Norfolk Island in 1856, and although some islanders later moved back. The island was deserted when Knowles and his boat reached it.

Eventually, Knowles and his men were able to build another boat and try again to get help, missing the populated islands of Polynesia; three of the men chose to stay on Pitcairn. If Knowles’ boat had missed Nuku Hiva, they would have probably been lost in the vast eastern Pacific. If Vandalia had not been fortuitously at Nuku Hiva, the natives probably would have killed them (see H-Gram 062, Battle of Nuku Hiva). Vandalia then sailed far out of her way to Oeno Island, rescuing everyone from Wild Wave except one who had died, and then proceeded to Pitcairn Island and rescued the remaining three. The story of the rescue made Vandalia and Commander Sinclair quite famous at the time.

Once in the Fiji Islands, Commander Sinclair determined that the waters around Waya Island were too shallow for Vandalia to reach. As a result, Sinclair chartered a schooner, Mechanic. A landing party of ten Marines, 40 sailors, a lightweight 12-pounder boat howitzer, and three Fijian guides, under the command of Lieutenant Charles Caldwell, embarked on Mechanic and departed for Waya Island on 6 October 1859. The offending tribe was aware the Americans were coming and sent messages to villages along the way bragging about what great warriors they were and how many people they had cannibalized, specifically the two white men.

Lieutenant Caldwell’s party landed on Waya at 0300 in the morning. They mounted the cannon on the wheeled carriage and proceeded to make a hair-raising climb in the dark up the steep mountainside to reach Somatti village. As they neared the crest by daybreak, the cannon broke loose, fell down a 2,300-foot drop, and was demolished. When they got to the top, the Americans found about 300 warriors arrayed in front of the village of Somatti in full Fijian “battle dress” including their “death robes” and headgear that was as much as six-feet wide (which a Marine later said made them a better target ). The Fijians were armed with clubs, spears, arrows, stones, and a few muskets. The Americans were armed with swords and carbines.

Lieutenant Caldwell ordered a flanking maneuver that apparently caught the Fijians by surprise as that was not how they traditionally fought. In the 30-minute one-sided battle that followed, at least 14 Fijian warriors, including two chiefs, were killed and another 36 wounded, before they retreated into the jungle. Two Marines were wounded by musket fire, while a third was hit in the leg by an arrow. Two sailors were badly hurt by rocks, and one merchant sailor from Wild Wave (three had joined the expedition) was hurt. While Caldwell’s group remained deployed to fend off any counter-attack, the gun crew set fire to the 115 huts in the village. With the village destroyed, Caldwell’s group retreated back down the mountain, driving off a couple attempts by the warriors to get in parting blows.

Once down the mountain, Caldwell’s group tarried in a friendly Fijian fishing village, whose inhabitants were quite pleased at what happened to the Somatti warriors, as they too had often been brutalized by them (and a few eaten). With the outbreak of civil war imminent, interest by the U.S. Navy in the South Seas islands diminished considerably. Fiji largely became a British problem and later a British colony in 1874.

Charles H. B. Caldwell went on to serve with distinction in command of the Union gunboat Itasca, the ironclad Essex and two other ships on blockade duty during the American Civil War.

During the civil war, Captain Arthur Sinclair (III) sided with the Confederacy. In January 1865, he was aboard the blockade-runner Lelia (he was to assume command for the final run from Nassau, Bahamas to Charleston) when the over-loaded Lelia sank in a storm shortly after leaving Britain and he went down with the ship (only 12 of 47 aboard were saved). His son, Arthur Sinclair (IV), also fought for the Confederacy. He was the only officer to serve aboard both CSS Virginia in her fight with USS Monitor in 1862 and aboard CSS Alabama when she was sunk by USS Kearsarge in 1864 (and survived both). Clemson-class destroyer DD-275 (1919–35) was named for Sinclair’s father, Arthur Sinclair (II), who served in the War of 1812. His grandson was Upton Sinclair, author of the famous muckraking book, The Jungle.

Sources include: Charles H. Lagerbom,“Wreck of the Clipper Wild Wave,” Courier Gazette, last modified 15 April 2021; NHHC Dictionary of American Fighting Ships (DANFS); Arthur Sinclair,“Cruise of the US Sloop of War Vandalia in the Pacific in 1858 under the command of Commander Arthur Sinclair,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, April 1889, Vol. 15/2/49; U.S. Naval Institute,“Irregular Warfare and the Vandalia Expedition in Fiji,” Naval History blog, last modified 9 October 2010.