H-069-1: "The Covered Wagon”—USS Langley (CV-1)

The first U.S. Navy aviation ship (not a term used at the time) was the converted coal barge USS George Washington Parke Custis, modified by then-Commander John Dahlgren to serve as a platform for generating gas and launching a tethered manned observation balloon. On 10 November 1861, the barge was towed by a steamer from the Washington Navy Yard down the Potomac to a position near Indian Head. The next day, the balloon was sent aloft with Professor Thaddeus Lowe, chief aeronaut of the Union Army’s Balloon Corps, aboard, observing Confederate positions on the Virginia side of the Potomac. Additional barges were modified by Dahlgren and used as observation balloon vessels during the war. Dahlgren’s barge was the first U.S. Navy vessel used for the purpose, but unnamed barges had been used by the Army a few months earlier during the Peninsula Campaign along the James River below Richmond. On 3 August 1861, an observation balloon was launched from the steam tug Fanny and the aeronaut on board, John LaMountain, is credited with providing the first useful aerial reconnaissance of the Civil War.

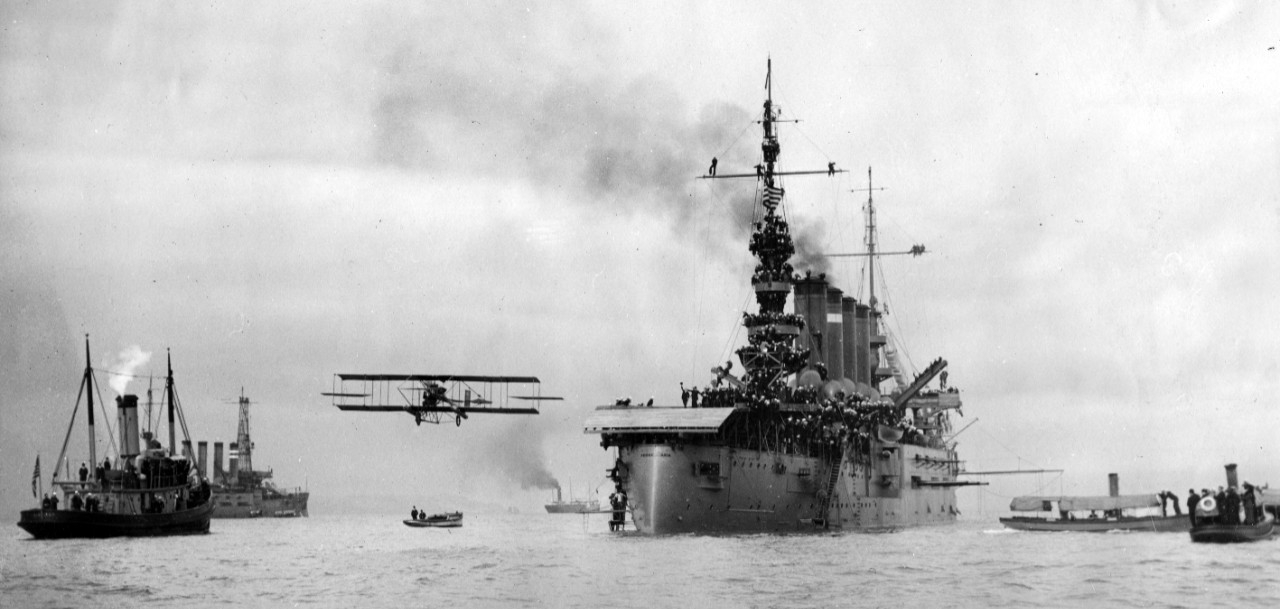

The concept of a “flat top” aircraft carrier originated with French inventor Clémont Ader in 1909 in his book L’Aviation Militaire (“Military Aviation”), which also described a ship with an island superstructure, a hangar bay, and deck elevators. The U.S. naval attaché in Paris reported the idea back to Washington. The U.S. Navy took an early lead, with the first launch of an aircraft from a stationary ship by Eugene Ely from the armored cruiser USS Birmingham (Scout Cruiser No. 2) in Hampton Roads on 14 November 1910. Ely then made the first landing (and turn-around launch) on the armored cruiser USS Pennsylvania (later Pittsburgh—Armored Cruiser No. 4) in San Francisco Bay on 18 January 1911. The British pilot Commander Charles Samson became the first to take off from a moving ship, the battleship HMS Hibernia, on 9 May 1912.

Meanwhile, the first seaplane had been invented by the French in 1910: The Fabre Hydravion was the first aircraft to take off from water under its own power. In December 1911, the French commissioned the first seaplane tender, Foudre, designed to lift aircraft into the water with a crane for launch and recover them the same way. In 1913, Foudre was further modified with a forward flight deck from which she could launch seaplanes.

The British protected cruiser HMS Hermes was temporarily modified to be used as an experimental seaplane carrier in April–May 1913. She was converted again from a cruiser to an aircraft ferry at the start of World War I, but was torpedoed and sunk by German submarine U-27 off Dunkirk, France, on 30 October 1914.

The first U.S. seaplane tender was the battleship USS Mississippi (Battleship No. 23), converted in December 1913. Although relatively new (commissioned February 1908), her “pre-Dreadnaught” design was obsolete before she was finished. Mississippi was reactivated from reserve status in January 1914 and used as an aviation support ship at the new Naval Air Station at Pensacola (constructed in 1913). Mississipi was under the acting command of Lieutenant Commander Henry C. Mustin (Naval Aviator No. 11), and carried seven aircraft, nine officers, and 23 enlisted men under the command of Lieutenant John H. Towers (Naval Aviator No. 3 and future four-star admiral), from Annapolis, tasked to set up a flight school at Pensacola.

In April 1914, Mississippi transported two seaplanes, a Curtiss AB-3 and an AH-3 hydro-aeroplane (and 500 Marines) to Vera Cruz, Mexico, to support the U.S. occupation of the city. The two seaplanes operated from shore under the command of Lieutenant Patrick Bellinger (Naval Aviator No. 8 and future vice admiral). Bellinger’s AB-3 took the Navy’s first recorded aerial photographs during wartime, carried out the first naval aviation mission in direct support of ground troops, and was the first to receive damage in battle (from ground fire). Mississippi was sold to Greece in July 1914, serving as a battleship and flagship of the Greek navy and then as a training vessel until being sunk by German Stuka dive-bombers on 23 April 1941.

First Air Attack from the Sea

The first air attack launched from a ship at sea occurred in September 1914 during the Japanese siege of the German colonial port in Tsingtao (now Qingdao) China. A Japanese Farman MF.7 floatplane from the seaplane tender Wakamiya dropped hand-carried bombs (which missed) on the Austro-Hungarian protected cruiser Kaiserin Elisabeth and a German gunboat. Upon the outbreak of war in August 1914, as allies of the British, the Japanese quickly made a move on the German colony and port at Tsingtao, which had been leased to the Germans by the Chinese Manchu regime. Anticipating the Japanese move, the commander of the German East Asia Squadron, Vice Admiral Maximilian von Spee, took his force to sea before the Japanese arrived. He attempted to reach Germany by crossing the Pacific and left only four German gunboats and one torpedo boat at Tsingtao, along with the Kaiserin Elisabeth (because of her prodigious coal consumption).

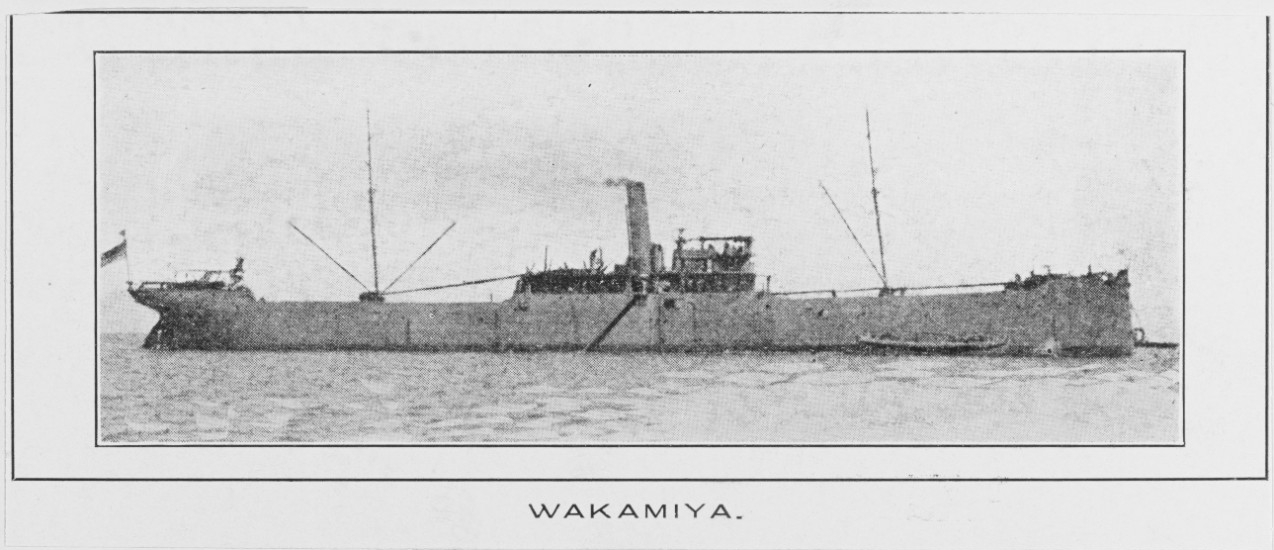

Japan declared war on Germany on 23 August 1914 and issued an ultimatum for the Germans to surrender Tsingtao, which was refused. On 2 September 1914, a Japanese naval force arrived to blockade the port, and put ashore 23,000 troops and 142 artillery pieces, which laid siege to the city. Part of the Japanese force was Japan’s first seaplane carrier, Wakamiya, converted from a transport captured from the Russians in 1905 during the Russo-Japanese War, and just commissioned that 17 August. Wakamiya carried four Japanese-built, French-designed Maurice Farman MF.7 biplane floatplanes (two on deck and two disassembled in the hold in reserve). The floatplanes were lowered by crane to the water and recovered from the water in the same manner.

On 5 September 1914, an MF.7 from Wakamiya flew a reconnaissance mission over Tsingtao, confirming the departure of the German squadron. In the meantime, a German gunboat managed to sink a Japanese destroyer. The MF.7 launched again with two hand-held bombs (equivalent to two 12-pounder artillery shells) and dropped them on the German gunboat Jaguar and Kaiserin Elisabeth without hitting either vessel. During the course of the next weeks, the MF.7s dropped 190 bombs in 49 missions, mostly against German land targets. On 30 September, Wakamiya struck a German mine. Although she did not sink, she required repairs and three of the MF.7s were put ashore to continue operations. One of them was shot down with a pistol (none of the aircraft was armed) by the only operational German aircraft at Tsingtao, which made the Japanese floatplane the first aircraft in history to be shot down in air-to-air combat.

Wakamiya was repaired and would be converted to an aircraft carrier (Japan’s first) in April 1920 and re-named Wakamiya-kan. She quickly became obsolete and was scrapped in 1932. Kaiserin Elisabeth was scuttled on 2 November 1914 before Tsingtao surrendered to the Japanese five days later. Von Spee’s force of two armored cruisers (Scharnhorst and Gneisenau) and three light cruisers made it across the Pacific, achieved a lopsided victory sinking two British armored cruisers in the Battle of Coronel off Chile, before having the misfortune to attempt to raid Port Stanley, Falkland Islands, just as two British battlecruisers arrived. HMS Invincible and HMS Inflexible ran down and virtually annihilated Von Spee’s force on 8 December 1914; only the light cruiser Dresden managed to escape and over 1,800 Germans died.

The Second Air Attack from the Sea

The second air attack from the sea was launched by the British on Christmas Day, 25 December 1914, on the German Zeppelin base at Cuxhaven, Germany (so much for the holiday truce). The Zeppelin base was out of range of aircraft based in Britain (or France), and the British devised a plan to use three converted cross-Channel steamers as seaplane carriers to attack the base. The plan called for HMS Engadine, HMS Riviera, and HMS Empress to each launch three floatplanes, each armed with three 20-pound bombs. Escorted by cruisers, destroyers, and submarines, the seaplane carriers lowered the planes into the water near the entrance to Heligoland Bight. The planes were a hodgepodge of three different types of Short-built “Folders.” In the freezing weather, two planes would not start, so seven planes conducted the reconnaissance and raid.

Fog, cloud cover, and anti-aircraft fire prevented the British aircraft from doing significant damage to facilities at Cuxhaven (propaganda art notwithstanding). Three aircraft made it back to their tenders and were recovered after a three-hour flight. Three others were rescued by the British submarine E-11 and the aircraft scuttled. The seventh aircraft ditched only eight miles off Heligoland, but luckily the pilot was rescued by a Dutch fishing trawler and was able to make his way back to England.

The German naval air arm (Marine-Fliegerabteilung) attempted a counter-attack on the British force. Empress had boiler problems and fell behind the force, and was attacked by two German seaplanes, with one small bomb missing by only 20 feet. Zeppelin L-6 then attacked Empress with bombs and machine-gun fire while Empress could only return fire with rifles as her 12-pounder was masked by the superstructure. In the end, neither the ship, seaplanes, nor Zeppelin suffered any significant damage.

Engadine would become the first aviation ship to participate in a major sea battle, launching seaplanes to conduct surveillance of the German High Seas Fleet in May 1916 at the Battle of Jutland. The British seaplane tenders would survive the war, but Engadine would ultimately meet her end as the SS Corregidor, striking a U.S. mine at the entrance to Manila Bay on 16 December 1941 while fleeing the Japanese invasion with 1,200–1,500 refugees aboard, of whom only 275 ultimately survived.

A Brief History of the Origin of Torpedo Bombers

Captain (later Rear Admiral) Bradley Fiske, U.S. Navy, is credited with conceiving the idea of using aircraft to carry torpedoes. Between 1910 and 1912, Fiske worked out the mechanics of launching aerial torpedoes, as well as tactics that included night attack when the target was less capable of defending itself. However, planes capable of carrying a torpedo were not built until late 1912, and Congress refused to appropriate funds for additional aerial torpedo research until 1917. Thus, the Italians were the first to test-launch an aerial torpedo in February 1914, with the British following suit on 27 July 1914. This led to the development of the first purpose-built operational torpedo plane, the Short Type 184, with construction commencing in 1915. In November 1914, the Germans first experimented with dropping torpedoes from Zeppelins at Lake Constance.

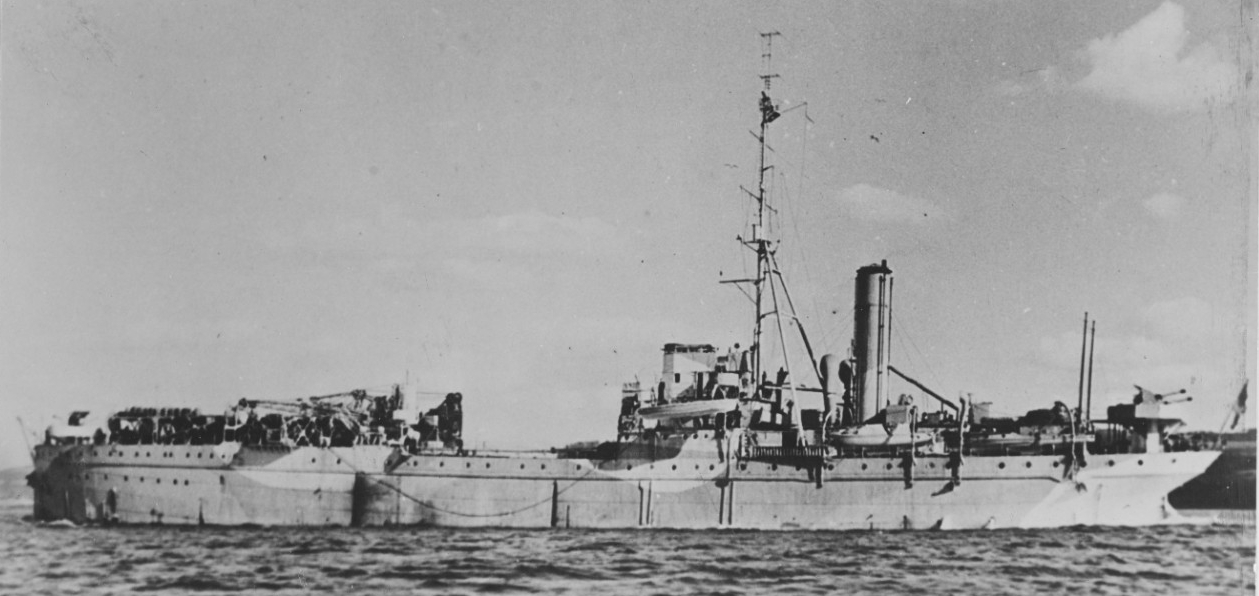

In March 1915, the British seaplane carrier HMS Ben-my-Chree, recently converted from a fast packet steamer, embarked two prototype Type 184 torpedo planes to support the Allied Gallipoli campaign at the entrance to the Dardanelles in Ottoman Turkey. The first aerial torpedo attack in history occurred on 12 August 1915, when Flight Lieutenant Charles Edmonds torpedoed a Turkish supply ship in the Sea of Marmara, although it turned out the Turkish ship was already beached as a result of being torpedoed by British submarine E-14. However, five days later, Edmonds sank a 5,000-ton Turkish steamer in the Sea of Marmara with a 14-inch aerial torpedo. Edmonds’ wingman was forced to land on the water due to engine trouble, but taxied in range of a Turkish tugboat and sank it with a torpedo. Ben-my-Chree would later be sunk by Turkish artillery on 11 January 1917, becoming the only aviation ship to be lost in the war by any side.

The first German aerial torpedo attack occurred on 1 May 1917 when a German seaplane torpedoed and sank the 2,800-ton British steamship Gena off Suffolk, England. Gena managed to shoot down another German seaplane as she was sinking.

HMS Furious in 1918, with palisade windbreaks raised on her flying-off deck, forward. Note that her dazzle camouflage pattern is carried up onto the palisade strakes (NH 89134).

First Carrier-Launched Attack

The first air attack from an aircraft carrier occurred on 18 June 1918, when the British carrier HMS Furious launched six Sopwith 2F.1 aircraft (a variant of the Sopwith Camel fighter) against the German Zeppelin base at Tondern (in what is now southern Denmark). Furious was the last of three Courageous-class battlecruisers, originally designed to be armed with two 18-inch guns and the largest in the world. The first two were completed as battlecruisers, but British enthusiasm for this ship class waned significantly after the catastrophic loss of three battlecruisers during the Battle of Jutland in May 1916. As a result, Furious was modified to be an aircraft carrier, with her forward turret removed and a replaced with a 10-plane hangar and a 160-foot flight deck added forward. The flaw in this design was quickly apparent as aircraft attempting to land had to maneuver around the battlecruiser’s superstructure.

On 2 August 1917, Squadron Commander Edward Dunning, British Royal Naval Air Service, recovered on Furious in a Sopwith Pup, the first landing by an aircraft on a moving ship. Dunning was killed five days later on his third landing attempt, when an updraft knocked the plane overboard and he drowned while unconscious in the cockpit. Further landing attempts were abandoned. Thus, Furious initially could launch several Sopwith Pup aircraft, but could not recover them. As a result, the ship was modified again with a 300-foot flight deck added in place of the aft turret, but turbulence was still a major issue.

By 1918, Furious embarked the new 2F.1a Ship’s Camel variant of the Sopwith Camel, which could carry 80- to 100-pounds of bombs. A plan was devised to attack the German Zeppelin base at Tondern. The first attempt on 18 June 1918 was stymied by high winds, making launch out of the question, and the second on 17 July by a thunderstorm. The next attempt, designated Operation F7, took place on 19 July. The plan called for Furious to launch seven Camels in two waves, each armed with two 50-pound Cooper bombs.

Furious approached through heavily mined waters to 12 nautical miles of the German coast and commenced launching the first wave of three Camels at 0313 and then a second wave of four Camels by 0321. One of the aircraft in the second wave quickly developed engine trouble and was forced to ditch. The pilot was rescued. The Camels flew 80 nautical miles to Tondern, with the first wave arriving at 0435 with complete surprise. Ground fire was ineffective and only one Camel was damaged. Two Zeppelins (L-54 and L-60) were destroyed in the largest airship shed, although German firefighters were able to save the massive structure. Ten minutes later, the second wave destroyed a captive balloon in one of the two smaller sheds.

Low on fuel, only one Camel made it back to Furious, but ditched nearby, with the pilot rescued. A second was forced to ditch, but the pilot was rescued by a British destroyer, while a third aircraft and pilot disappeared. The three other aircraft pilots opted to land in neutral Denmark, where they were interned, but escaped a few weeks later on a freighter.

More on Torpedo Bombers

In 1915, Rear Admiral Fiske had written about using torpedo bombers to attack ships in port, so long as the water was shallow enough. Following the Tondern raid, the British subsequently developed a plan to do just that. The plan was to attack the German High Seas Fleet (which had refused to give battle since Jutland) in port using the new Sopwith Cuckoo, which was the first plane specifically designed for carrier operations (to include folding wings) and which could carry a 1,000-pound torpedo. However, an insufficient number of Cuckoos were available before the Armistice went into effect on 11 November 1918.

The U.S. Navy finally began testing aerial torpedoes in 1917. The first test on 14 August in Huntington Bay, Long Island, was not auspicious as the dummy torpedo porpoised out of the water and nearly hit the F-5L flying boat that had dropped it. However, it was a start. The Navy bought its first torpedo bombers, 10 Martin MB-1 variants (twin-engine land-based aircraft), in 1921. The Navy declined to use torpedo bombers during the famous bombing tests by General Billy Mitchell against stationary ships in July 1921. (Actually the Navy had conducted its own bombing tests in November 1920, sinking the obsolete battleship Indiana with Navy aircraft. Te test was somewhat rigged in that sand bombs were used and high explosives placed on the ship simulated bomb damage.) The Navy did conduct tests using torpedo bombers and torpedoes with dummy warheads against a formation of four battleships steaming at 17 knots. The results were a real wake-up call as to the danger posed by torpedo bombers.

The First Aircraft Carriers

Originally laid down as a merchant ship, HMS Ark Royal was commissioned on 10 December 1914. Designed as a hybrid to tend seaplanes and launch aircraft from a forward platform, she was arguably the first aircraft carrier. However, she could only recover the seaplanes; the aircraft had to land ashore. Too slow to operate with the British battle fleet, she supported the Gallipoli campaign in Turkey, where her aircraft conducted observation and reconnaissance missions.

In January 1918, aircraft from Ark Royal attacked the German battlecruiser Goeben (re-named Yavuz by then, but still crewed by Germans) when she sortied from Turkey, where she had been bottled up since 1914. Beached after hitting several mines, Yavuz was hit by two bombs from Royal Naval Air Service aircraft, which did minimal additional damage. (Yavuz was to serve in the Turkish Navy until 1950, but wasn’t scrapped until 1976, the last dreadnought in the world other than the USS Texas (BB-35) museum ship in San Jacinto.)

After the war, Ark Royal served as an aircraft ferry and depot ship supporting White Russian and British anti-Bolshevik operations in the Black Sea during the Russian Civil War, as well as taking part in British operations in British Somaliland in 1920. Her name was changed to Pegasus in 1934, to free the name for a new aircraft carrier, and she served during World War II as a prototype catapult-fighter ship, in which fighter aircraft would be launched to protect convoys, but would have to ditch in the sea afterward and the pilot rescued. Pegasus was scrapped in 1950.

Of note, the Royal Naval Air Service was merged with the British Army Flying Corps on 1 April 1918 to form the Royal Air Force (RAF), the first independent air force in the world. The Fleet Air Arm was formed in 1924 for carrier and ship-based aviation, but was subordinate to the Royal Air Force until 1937, when it was re-subordinated to the Royal Navy. Land-based maritime patrol and anti-submarine aircraft remained under the RAF.

The first ship with a full-length flight deck was HMS Argus, converted from an ocean liner and commissioned on 16 September 1918, too late to participate in World War I. She served as the British test platform for developing carrier aviation systems, aircraft, tactics, and doctrine. She made one deployment to the China Station in the late 1920s before being placed in reserve due to funding shortfalls. She was returned to service in World War II as an aircraft ferry, taking planes to Malta, West Africa, Iceland, and to Murmansk, Russia. She was pressed back into service as an aircraft carrier due to loss of other British carriers and provided air cover during Operation Torch, the Allied invasion of North Africa, in November 1942. Argus was scrapped in 1947.

HMS Hermes was the first ship laid down to be an aircraft carrier, on 15 January 1918. However, Hermes was not completed and commissioned until 18 February 1924. She was the first aircraft carrier to have an offset “island” superstructure. Hermes was commissioned two days before HMS Eagle, which was a converted battleship that, like Hermes, had a full-length flight deck and offset island. Hermes would be sunk by Japanese carrier aircraft on 9 April 1942 near Ceylon in the Indian Ocean.

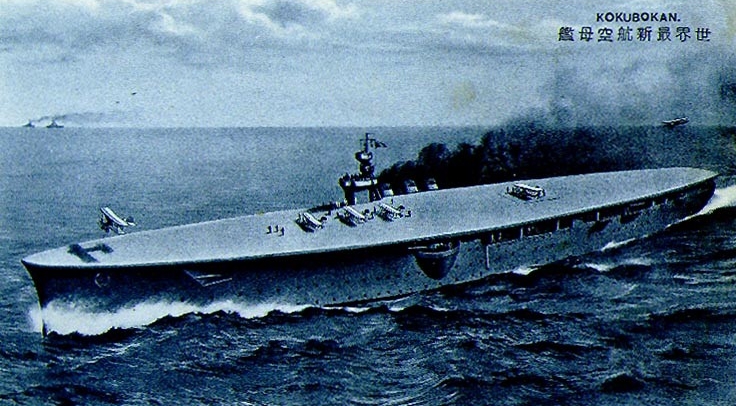

Japanese postal card, published circa 1921-22, depicting (rather inaccurately) the aircraft carrier Hosho, which was then under construction. Kokubokan ("aviation mother ship") is the Japanese term for aircraft carrier. The Japanese Kanji characters (reading from right to left) can be translated: "World's newest aircraft carrier" (NH 42374-KN).

In the meantime, the Japanese laid down their own purpose-built aircraft carrier, Hosho (“Phoenix Rising”), on 16 December 1920, borrowing much from the design of Hermes, but with a minimal island superstructure that would characterize following Japanese aircraft carriers. Hosho was commissioned on 27 December 1922, thereby becoming the first ship in any navy designed from the keel up to be an aircraft carrier. She was about 550 feet long and could embark about 15 aircraft. Like Hermes, Hosho would serve as the test platform for the development of Imperial Japanese Navy aircraft, systems, procedures, and tactics. She would participate in the Battle of Midway, providing air cover to the “Main Body” of Japanese battleships (which never got into the battle), and she would survive the devastating U.S. carrier raids on Kure Naval Base in 1945 with only minor damage. Hosho was scrapped in 1946.

In 1921, the British began converting Furious, which had conducted the Tondern raid, to a full-deck aircraft carrier, initially with no island at all. As Furious underwent conversion, her two sister battlecruisers, Glorious and Courageous, commenced conversion in 1924 under the terms of the Washington Naval Treaty of 1922. Furious was completed in September 1925, Courageous in February 1928, and Glorious in 1930. Furious survived numerous close-call combat actions during World War II, but Courageous became the first British warship to be sunk, torpedoed by U-29 on 17 September 1939. Glorious suffered a worse fate on 9 June 1940, when she was caught by surprise by German battlecruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, and sunk with virtually all hands and with both escorting destroyers (1,519 crewmen from the three ships were lost, with only 40 total survivors).

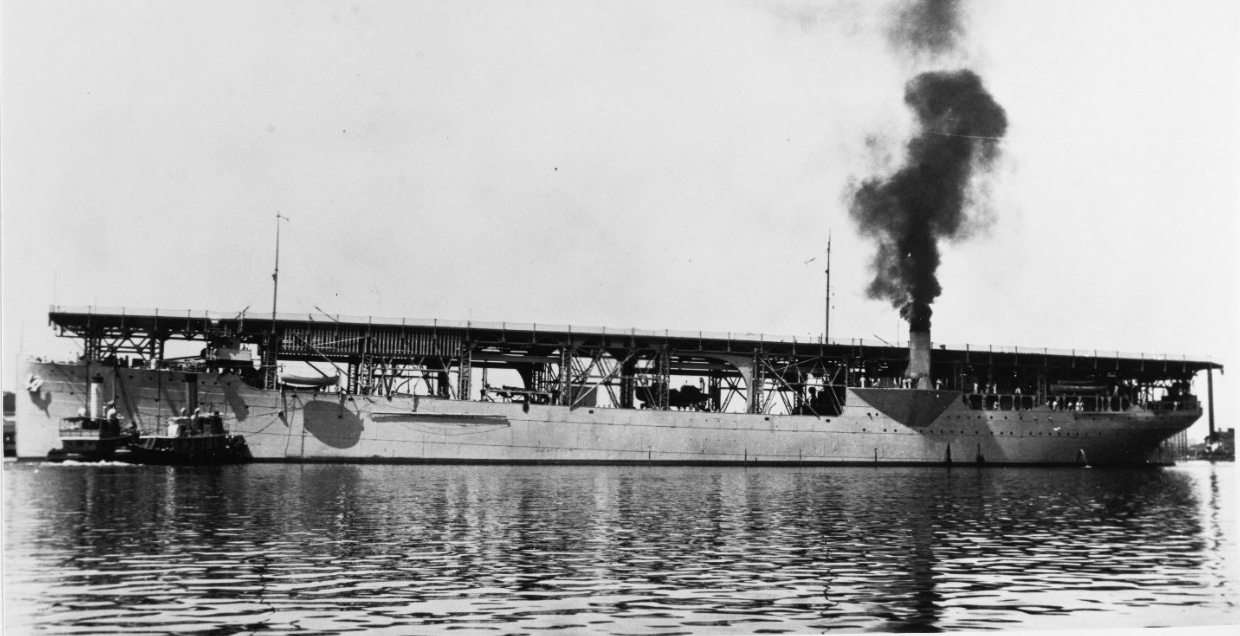

The first U.S. aircraft carrier was converted from the collier USS Jupiter. Jupiter was one of four Proteus-class fleet colliers laid down in 1910/1911 and commissioned in 1913 (Cyclops not until 1917). The large ships were 542 feet long and displaced almost 20,000 tons. Jupiter was laid down at Mare Island Shipyard on 18 October 1911, with President William Howard Taft present for the ceremony.

Jupiter was unique among the four colliers, in that she was the first U.S. Navy ship to have turbo-electric drive. Built by General Electric, Jupiter’s two (later three) boilers, single Curtis turbine, and two electric motors directly connected to two shafts could generate 7,000 horsepower per shaft and propel the ship at 15 knots, with a range of 3,500 nautical miles at 12 knots. By comparison, Cyclops (AC-4) and Proteus (AC-9) had reciprocating triple-expansion steam engines, while Nereus (AC-10) had a less-successful geared steam turbine drive. Jupiter was initially designated Fuel Ship No. 3, and later Collier No. 3 as oil came into increasing use as a fuel. In 1922, ship designations were standardized and the ships received AC (Auxiliary—Collier) designations.

The turbo-electric design was so successful that it was used in the aircraft carriers Lexington (CV-2) and Saratoga (CV-3), as well as in six battleships completed at the end of World War I and in two classes of destroyer escorts during World War II. It didn’t work as well when ships suffered flood damage.

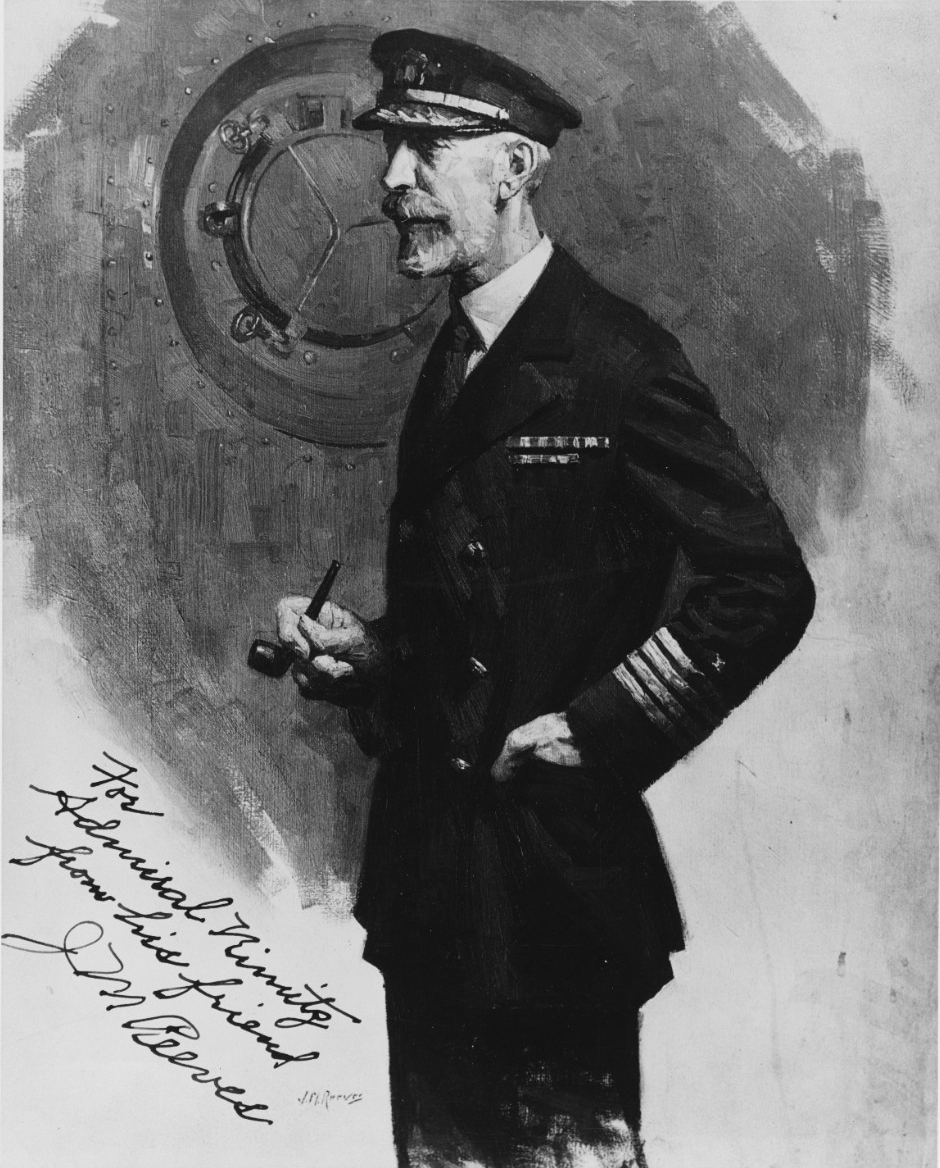

Self-Portrait by Captain J. M. Reeves, USN, autographed "For Admiral Nimitz from his friend J. M. Reeves" (NH 62658).

Jupiter was launched on 14 August 1912 and commissioned on 7 April 1913 under the command of Commander Joseph M. “Bull” Reeves. Reeves would later be known as the “father of carrier aviation,” although at that time he had no connection to flying, having served on the battleship Oregon during the Spanish-American War, as well as on other battleships before he assumed command of Jupiter—with a stint at the U.S. Naval Academy as head football coach in 1907 (9–2–1 and 6–0 over Army).

Reeves achieved designation as a naval aviation observer in 1925 and he assumed command of Aircraft Squadron, Battle Fleet. As commodore, his flagship was the Langley (CV-1), converted from Jupiter. In July 1933, Reeves was designated a four-star admiral as Commander, Battle Force, U.S. Fleet, and then in February 1934, he was designated Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Fleet, the senior-most position in the service after the Chief of Naval Operations. He retired in 1936, but was recalled to active duty in World War II as a vice admiral and served as senior military member of the Munitions Assignment Board and other key committees. He retired (again) as a four-star in 1947. As a flag officer, Reeves was an outspoken proponent of carrier aviation and led the integration of carriers into the Fleet as a key attack capability.

Following commissioning and sea trials, Jupiter transited from San Francisco to Mazatlan, Mexico, in April 1914, with a detachment of Marines embarked during the Veracruz crisis. On 12 October, Jupiter transited the Panama Canal, the first ship to transit from west to east (the first east-to-west ship transit occurred 3 August 1914). She then served as part of the Atlantic Fleet Auxiliary Division until the U.S. entry into World War I in 1917.

On 15 October 1915, Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels had asked the Navy General Board to review a proposal by the director of Naval Aeronautics, Captain Mark L. Bristol, to convert a merchant ship to operate aircraft. Daniels believed it was more important to determine how the fleet would use armored cruiser North Carolina, which had just been retrofitted to carry aircraft. On 5 November, Lieutenant Commander Henry C. Mustin made the first catapult launch from a commissioned warship off the stern of North Carolina, flying an AB-2 flying boat, in Pensacola Bay. North Carolina completed catapult calibration on 12 July 1916, becoming the first U.S. Navy ship equipped to carry and operate aircraft.

In a significant development in 1916, the General Board concluded that in the future, the Navy that had control of the air would have a decisive advantage. (The General Board, chaired by Admiral of the Navy George Dewey, was an advisory body formed after the Spanish-American War, consisting primarily of very senior flag officers, some without an assignment, but not yet at compulsory retirement age, which in theory made the board more objective in making recommendations to the Secretary of the Navy).

On 6 April 1917, the United States declared war on Germany and entered World War I. France quickly requested U.S. Naval Aviators be sent to France to conduct anti-submarine patrols against German U-boats. In response, the U.S. Navy formed Aeronautic Detachment No.1, under the command of Lieutenant Kenneth Whiting (Naval Aviator No. 16). Most of the detachment embarked on Jupiter to transit the Atlantic. About 60 nautical miles from the French coast, torpedo wakes were observed, one forward and one aft, narrowly missing the ship.

Jupiter arrived at Pauillac, France, on 5 June 1917. The detachment was the first organized U.S. military unit to arrive in France during the war. Whiting would be the key leader in the operations of U.S. naval aviation in Europe during the conflict. By 11 November 1918, U.S. naval aviation would grow from 54 aircraft, 1 airship, 3 balloons, 48 officers, and 239 enlisted men to 2,107 aircraft, 15 airships, 215 kite and free balloons, 6,716 officers, and 30,693 enlisted men. Over 570 Navy aircraft and 18,000 personnel were stationed abroad by the end of the war.

Sometime after 4 March 1918, Jupiter’s sister Cyclops disappeared without a trace in what later came to be called the “Bermuda Triangle” with the loss of all 15 officers, 221 enlisted personnel, and 70 passengers aboard (306 total), while carrying a cargo of 11,000 tons of manganese ore. No evidence has ever been found that German submarines had anything to do with her loss, which represents a non-combat personnel loss second only to the loss of all 340 aboard the frigate USS Insurgente in a storm in 1800. Of note, Jupiter’s other two sister ships were later sold into commercial service. Proteus was lost without trace in the “Bermuda Triangle” sometime after 23 November 1941 with all 59 crewmen. Nereus also disappeared in the same area with all 61 crewmen sometime after 10 December 1941. There is no evidence German U-boats had any involvement in their losses. Like Cyclops, Proteus and Nereus were carrying a cargo of heavy metal ore, for which they weren’t actually designed, suggesting a combination of storm and structural flaw more than anything to do with the “Bermuda Triangle” (see H-Gram 016/H-016-4 for more on Cyclops).

With the end of World War I and the decreasing use of coal as fuel, Jupiter was taken out of active service. On 11 July 1919, the Naval Appropriations Act for Fiscal Year 1920 was signed into law, authorizing the conversion of a collier into an aircraft carrier. Jupiter was selected because of the advantages of the turbo-electric drive, which took up less space and weight than the propulsion plants of the other colliers. Jupiter was decommissioned on 24 March 1920, after commencing conversion at the Norfolk Naval Shipyard, Portsmouth, Virginia. A second collier was planned for conversion, but this would be cancelled after limitations in the Washington Naval Treaty of 1922 resulted in the hulls of battlecruisers Lexington (CC-1) and Saratoga (CC-3) becoming available for conversion.

On 11 April 1920, Jupiter was renamed Langley after Samuel Pierpont Langley, an American physicist, astronomer, and early aviation pioneer. In 1866, he was appointed an assistant professor of mathematics at the U.S. Naval Academy, where he also restored the small Naval Academy observatory, originally built in 1854 (and rebuilt in 1991). He was only at the academy for a year. In the 1880s, he began experimenting with unmanned heavier-than-air aircraft, initially powered by rubber bands. He subsequently developed unmanned aircraft powered by steam (a miniature flash-boiler engine). The aircraft was known then as an “aerodrome.” Langley launched aerodromes by catapult from a barge in the Potomac River that would land in the water, as the craft had no landing gear.

After a number of failures, Langley was finally successful on 6 May 1896, when Aerodrome No. 5 made two flights, the longest to a distance of 3,300 feet (ten times farther than any previous heavier-than-air flying machine in the world). Aerodrome No. 6 flew 5,000 feet. In 1898, he was awarded grants from the War Department and the Smithsonian to develop a manned aerodrome. Although the Wright Brothers achieved manned powered flight first, Langley continued his experiments. Both tests were failures when the manned aerodrome crashed into the Potomac after being catapulted from the barge on 7 October and 8 December 1903 (the pilot was rescued both times). The Smithsonian would subsequently display the aircraft, claiming it was “the first man-carrying aeroplane in the history of the world capable of sustained free flight.” This, however, was not true, although it came to be widely believed in the early 1900s.

Jupiter had six coal bunkers. Bunker No. 1 was converted to hold aviation fuel (578 tons). An elevator was built into the upper part of Bunker No. 4 to take aircraft from the main deck to the flight deck. However, even when the elevator was completely lowered, it stood about three feet above the main deck, resulting in aircraft having to be lifted onto the elevator by a gantry crane that ran the length of the ship under the flight deck. The weapons magazine was located under the elevator machinery. The other bunkers were converted to hold machine shops and spare aircraft and parts. Langley had no actual hangar bay. Aircraft were kept on the main deck, where they were essentially exposed to the elements through the lattice steel that supported the flight deck (it was the flight deck above the lattice steel that gave Langley the nickname “Covered Wagon”).

Langley had a full-length flight deck with a catapult at the bow and arresting wires both forward and after so the ship could recover aircraft while steaming either ahead or reverse (this feature was carried through the Yorktown class). The bridge was actually under the flight deck, and her multiple stacks would be reconfigured several times over the course of her service to try to reduce turbulence issues. Langley was armed with four single 5-inch/51-caliber guns for defense against surface targets.

Langley also had a carrier-pigeon loft on the stern (pigeons had been used to send messages from U.S. Navy aircraft engaged in surveillance and anti-submarine operations in World War I, with surprising success). However, at one point, Langley’s entire flock “flew the coop” off Tangier Island and roosted at Norfolk Shipyard. (Lexington and Saratoga also had pigeon lofts in their original design.)

As Langley was nearing completion, the Washington Naval Treaty was signed on 6 February 1922. Believing that the naval arms race between Britain and Germany was a major cause of World War I, there was intense political pressure after the war to prevent further such competitions, which were also extremely expensive. Also, because the Germans had scuttled virtually their entire fleet at Scapa Flow on 21 June 1919, it was thought there would be no more need for large navies as a result of the “war to end all wars.” When Harding administration’s Secretary of State, Charles Evans Hughes, announced the U.S. proposals at the first plenary session in November 1921 (not coordinated with Navy leadership), he was hailed by the press as having sunk more battleships than all the admirals combined. The proposal called for suspension of all capital ships under construction and a moratorium on capital ship construction for at least 10 years (and this is why all the U.S. battleships at Pearl Harbor were over 20 years old). However, Article VIII of the Washington Naval Treaty exempted experimental aircraft carriers in existence or under construction by 12 November 1921, sparing Langley from dismantlement.

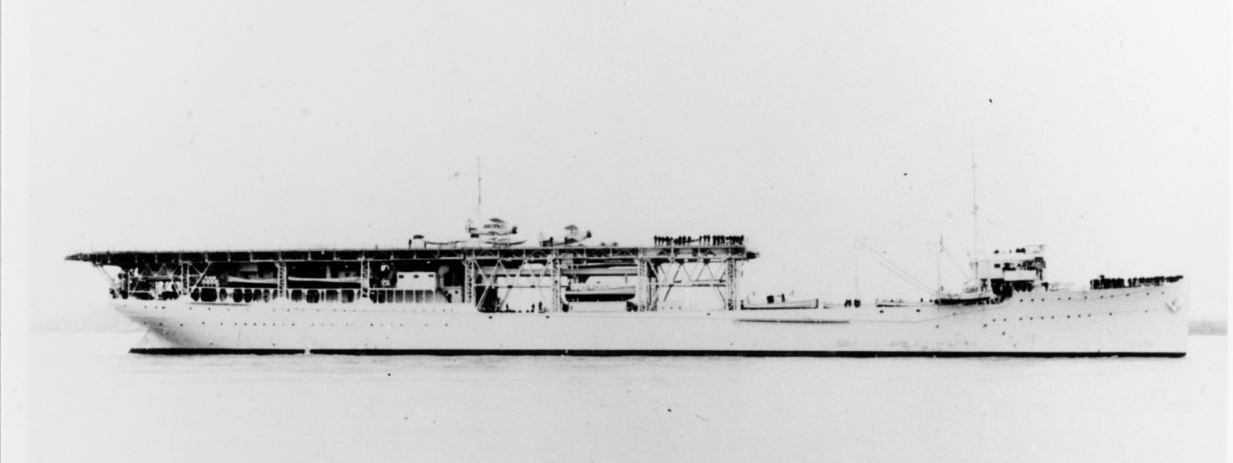

Langley was commissioned as an aircraft carrier (CV-1) on 20 March 1922 ("CV" stands for Cruiser—heavier than air). Her executive officer was Commander Kenneth Whiting, who served as her acting commanding officer until relieved by Captain Stafford “Stiffy” Doyle on 16 June 1922. Doyle was not an aviator, although he had previously commanded the Norfolk Naval Air Station. In 1918, Whiting had in fact proposed to the General Board that a collier be converted to an aircraft carrier, and his initiative had become reality. Doyle nevertheless also became an outspoken proponent of building more aircraft carriers.

With a top speed of 15 knots, Langley would not be able to keep up with other fleet units, so the nature of her operations were truly experimental. On 17 October 1922, Lieutenant Commander Virgil C. “Squash” Griffin (Naval Aviator No. 41) made the first carrier launch in U.S. history in a Vought VE-7SF Bluebird (the U.S. Navy’s first fighter aircraft) while Langley was at anchor in the York River. This was actually quite sporty since it turned out that VE-7s frequently did not gain sufficient flying speed with the carrier at anchor. However, the 52-foot drop from the flight deck resulted in sufficient speed to get airborne. Also, the VE-7 had no brakes and had to be held in place during engine run-up by a bomb-release contraption hooked to a restraining wire that was triggered when a flight deck crewman tugged on a line.

On 26 October, Lieutenant Commander Godfrey DeCourcelles Chevalier (Naval Aviator No. 7) made the first “trap” on board Langley in an Aeromarine 39B, a two-seat trainer that could be quickly converted into a floatplane, as Langley steamed off Cape Henry, Virginia. Chevalier, a World War I hero with a Distinguished Service Medal (then higher than a Navy Cross) died on 14 November 1922 as result of injuries sustained in a crash of a VE-7 two days earlier near Lockhaven, Virginia. (Fletcher-class DD-451 was named in his honor. After the loss of DD-451 in the Central Solomon Islands in 1943 following several heroic battles, Gearing-class destroyer DD-805 was named in his honor, served from 1944 to 1975, and was awarded nine Battle Stars in the Korean War.)

On 18 October 1922, Commander Whiting got the first “cat shot” from an aircraft carrier, catapulted in a PT seaplane while Langley was at anchor in the York River. PT seaplanes were floatplanes built from surplus spare parts at the Naval Aircraft Factory, which had been established in Philadelphia in 1918 to assure an adequate supply of aircraft parts since the Army had largely cornered the commercial market.

By January 1923, Langley was conducting flight testing in the Caribbean (better weather). In June 1923, she arrived at the Washington Navy Yard to give flight demonstrations to various dignitaries. She then conducted a “publicity cruise” that included Bar Harbor and Portland, Maine; Portsmouth, New Hampshire; Gloucester and Boston, Massachusetts; and New York City. After more exhibitions and training in 1924, Langley transited to the Pacific to be homeported at San Diego. In January 1925, Fighting Squadron TWO (VF-2) became the first fighter squadron assigned to a carrier, still flying the VE-7S fighter.

Different types of catapults and arresting gear were tested aboard Langley during the following years. Other innovations included tailhooks, replacing hooks and “combs” attached to the landing gear cross brace. Netting was rigged outboard of the flight deck so crewmen could dive to safety (and not into the ocean) in the event of an accident on the flight deck, which was fairly common. Formalized aircraft handling and maintenance crews were organized, along with the institution of colored flight-deck jerseys signifying specific jobs. Standardized hand signals were established because the aircraft didn’t have radios yet. Whiting directed that all recoveries be filmed with a motion picture camera, the forerunner of the PLAT camera. Experiments were conducted with different landing approaches, with the left-hand circuit, slow flat turn, nose-high attitude relying on power becoming the standard. Experiments also included flight-deck lighting and night landings. One of the most important innovations was the creation of the “landing signal officer” (LSO), to guide aircraft on final approach to the flight deck.

Langley initially carried a squadron of about 12 aircraft and several utility aircraft. A major challenge was the bottleneck caused by the elevator/crane combination in bringing aircraft from the main deck to the flight deck. When Commodore Reeves came aboard as Commander Aircraft Squadrons, Battle Fleet, he instituted a radical change that broke with standard practice in the British and Japanese (and U.S) navies by spotting aircraft on the flight deck in a “deck park” and keeping them there. As a result, Langley could carry 34–36 aircraft on the flight deck with six stowed below. Of course, this necessitated new procedures (and a lot more work) of moving aircraft around the deck to enable the much faster launch and recovery cycle. (Of note, Reeves was the first aviator to achieve flag rank.)

During Fleet Problem VII in March 1927, under the direction of Rear Admiral Reeves, Langley’s aircraft successfully “attacked” the Panama Canal. In Fleet Problem VIII during April 1928, Langley’s aircraft (two squadrons of new Boeing F2B-1 fighters) achieved total surprise in an exercise air attack on Pearl Harbor (the first of several, actually, over the next years). Langley was able to launch 35 aircraft in seven minutes for an early morning “attack.” In 1929, Langley was the star of the Hollywood silent film The Flying Fleet, in which two Navy pilots are rivals for the love of the same woman.

Langley would be followed by the much larger Lexington and Saratoga, built on unfinished battlecruiser hulls, upon which construction had been suspended due to the Washington Navy Treaty. The treaty permitted such hulls to be converted to aircraft carriers (although there was total tonnage cap for carriers). The Japanese took advantage of this as well with Akagi (a converted battlecruiser hull) and Kaga (a converted battleship hull), as the British already had with the Courageous-class carriers (converted battlecruisers). Lexington and Saratoga were 888 feet long, 48,000 tons, could carry over 80 aircraft, and had speed well in excess of the Battle Fleet. Lexington was commissioned in December 1927 and Saratoga in November 1927. Akagi was commissioned in August 1927 and Kaga in November 1929.

The first U.S. aircraft carrier designed from the keel up was Ranger (CV-4), laid down in 1931 and commissioned in 1934. Ranger was not that much larger than Langley and much smaller than Lexington and Saratoga. In 1934, Congress “helpfully” passed legislation requiring that the “experimental” Langley be included in the carrier tonnage total. With construction of the three Yorktown (CV-5) class carriers commencing in 1934, in order to keep total carrier tonnage under the treaty limit, Langley had to go. The solution was to remove about one third of Langley’s flight deck (the forward third) and repurpose her as a seaplane tender.

The conversion of Langley at Mare Island Shipyard was completed on 26 February 1937 and she was designated AV-3. She then tended flying boats at Seattle, Sitka, Pearl Harbor, and San Diego, with a short deployment to the Atlantic Fleet in February–July 1939. She then transited to Manila, Philippines, arriving on 24 September 1939, where she served as a tender for PBY Catalina flying boats, usually at Cavite.

At the direction of Admiral Thomas C. Hart, Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Asiatic Fleet, Langley departed Cavite just ahead of the 10 December 1941 Japanese attack with orders to proceed south to the Dutch East Indies, out of range of land-based Japanese bombers. As the Japanese advanced, Langley subsequently arrived at Darwin, Australia, on 1 January 1942, where she assisted in anti-submarine patrols until 11 January, when she was ordered south to Freemantle to serve as an aircraft ferry and embark 32 P-40 fighters and their U.S. Army Air Force pilots and ground crew chiefs. As a result, Langley missed the devastating Japanese carrier strike on Darwin on 19 February. Reports of the presence of an “aircraft carrier” (Langley) were a reason the Japanese carrier force attacked Darwin.

Departing Freemantle on 22 February 1942 with a convoy destined for Ceylon, Langley subsequently had a sudden change of orders to take the fighters to Tjilatjap, a port on the south coast of Java. This was a desperate last-ditch effort to augment Allied fighter cover over Java, which by that time had been virtually annihilated, allowing Japanese bombers to operate with near impunity over Java and the entire Dutch East Indies.

In a tragic series of command-and-control errors and other delays, Langley wound up making her final suicidal run into Tjilatjap in broad daylight on 27 February. She was attacked by 16 Japanese Navy G4M Betty twin-engine bombers from newly occupied Bali. Flying above effective fire from Langley’s woefully inadequate anti-aircraft guns, the Bettys could bomb at their leisure.

Superb handling of the old ship by Commander Robert P. McConnell narrowly avoided bombs dropped by the first two bomber attacks, but when the Japanese made a third attack, they had learned McConnell’s tricks, and Langley was struck by five bombs (one of the most accurate attacks by horizontal bombers against a moving ship in the entire war). Despite heroic damage-control efforts, the damage was fatal, although it took time for Langley to sink. She had to be helped along by gunfire and two torpedoes from an escorting destroyer, USS Whipple (DD-217).

Somewhat miraculously, only about a dozen of Langley’s 484 crew were lost as result of the bombing. The survivors were picked up by destroyers Whipple and Edsall (DD-219) and transferred to the oiler Pecos (AO-6) to proceed to Australia. There the miracle ended when the unescorted Pecos was bombed and sunk on 1 March by Japanese carrier dive-bombers. Only Whipple was able to reach the scene (Edsall was sunk while trying), rescuing 232 survivors of almost 700 aboard Pecos. However, Whipple was forced to leave due to several submarine contacts. Officially, 456 of the combined crews of Langley and Pecos were lost. However, an imprecise number of survivors of other ships previously sunk was aboard Pecos, so the total lost at sea may have been closer to 500.

One of the few survivors was Commander McConnell, the last commanding officer of the venerable Langley. Subsequently, he would be unfairly accused of not doing everything possible to save his ship and of not upholding the highest traditions of the U.S. Navy. After reviewing the evidence, the Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral Ernest J. King, summarily rejected the charge and quashed the formal inquiry. Thus ended the sad finale of one of the most consequential ships ever to serve in the U.S. Navy. (For more detail on the loss of Langley, please see H-Gram 003 and H-Gram 067.)

____________

Sources include: NHHC Dictionary of American Fighting Ships (DANFS); United States Naval Aviation 1910–2010, Vol. I, Chronology, by Mark L. Evans and Roy A. Grossnick, Naval History and Heritage Command, 2010; “Aircraft Carrier Number 1,” by Norman Polmar, Naval History Magazine, April 2022, Vol. 36, No. 2.; “From Floating Fuel Farm to First Flattop, the “Covered Wagon” Was a Trailblazer,” by Edward Lundquist, issuu.com; “History’s First Seaborne Airstrike Took Place in East Asia,” by Franz-Stefan Gady, in The Diplomat, thediplomat.com, 2 November 2019; The Naval Bombing Experiments Off the Virginia Capes, June and July 1921, by Vice Admiral Alfred W. Johnson (Ret.), Navy Department Library, 1959; “The Epic Story of the First Aircraft Carrier Raid in History,” by Sebastien Roblin, in The National Interest, nationalinterest.org, 11 September 2020; Rising Sun, Falling Skies: The Disastrous Java Sea Campaign of World War II, by Jeffrey R. Cox, Osprey Publishing, 2014.