H-Gram 081: A Legacy of Valor—Commander Hugh W. Hadley and Steward’s Mate First Class Charles J. French

6 March 2024

Download a PDF of H-Gram 081 (2 MB).

One of the responsibilities of Naval History and Heritage Command is to provide recommended ship names to the Secretary of the Navy, consistent with the traditional naming convention for that type of ship. The Secretary has sole authority for naming U.S. Navy ships. The only actual congressionally mandated directions for naming ships are that battleships must be named after states (not an issue any more) and no two ships in commission at the same time can have the same name. Everything else is “tradition” (i.e., the rules are there are no rules) and Secretaries of the Navy have been breaking the “rules” since the first Secretary, Benjamin Stoddert, named one of the first six frigates USS Chesapeake, because that’s where he had his home.

Nevertheless, last summer Secretary Carlos del Toro asked me to provide a list of 25 potential names for future Arleigh Burke–class guided missile destroyers. In keeping with my personal philosophy that ships should be named after combat heroes, or heroic ships, this gave me an excuse to compile my “all-time” names that I find to be most inspirational. In December 2023, the Secretary took my top pick off that list, naming DDG-141 after Commander Ernest Evans, commanding officer of the destroyer USS Johnston (DD-571), who was awarded a posthumous Medal of Honor for his actions during the Battle off Samar on 25 October 1944. In January, the Secretary took another off my list, naming DDG-142 for African-American Steward’s Mate First Class Charles Jackson French, known as the “Human Tugboat” for his heroic actions in a little-known night battle off Guadalcanal on 4–5 September 1942, for which he was recommended for a Navy Cross, but received a Letter of Commendation instead (upgraded to a posthumous Navy-Marine Corps Medal in 2022).

About the same time that SECNAV was announcing the USS Charles J. French, I received a request for information (RFI) from the commander of U.S. Naval Forces Central Command/U.S. Fifth Fleet, Vice Admiral Brad Cooper. The RFI noted that in October 2023, the guided missile destroyer USS Carney (DDG-64) had shot down a total of 19 (Houthi) anti-ship missiles and attack drones (and subsequently shot down many more). His question was, which U.S. Navy surface ship has shot down the most aircraft?

It turns out that the cumulative record by a single surface ship is, somewhat surprisingly, not known. However, the record for a single ship in a single engagement is held by the destroyer USS Hugh W. Hadley (DD-774), with 23 aircraft destroyed (20 shot down and three kamikazes that crashed into the ship) off Okinawa on 11 May 1945. This is also quite likely the cumulative record for a single surface ship.

Commander Hugh W. Hadley is also on the list that I provided to the SECNAV, not only for his own actions, which earned a posthumous Silver Star, but also for those of the crew of the ship named after him, which earned a Presidential Unit Citation and a Navy Cross for her commanding officer. Commander Hadley was killed on the bridge of fast transport USS Little (APD-3) in the same battle in which Steward’s Mate First Class French performed his heroics. Thus the impetus for this H-gram, which attempts to weave the threads of valor from one action to another, and to demonstrate my belief that the most important purpose of a ship’s name is to inspire its crew to greatness.

The Sacrifice of TRANSDIV 12

On 15 August 1942, five days after the U.S. Navy “abandoned” the U.S. Marines on Guadalcanal, four navy fast transports (APDs) of Transport Division (TRANSDIV) 12 arrived off Lunga Point and unloaded ammunition, aviation gasoline, aviation maintenance gear, and about a hundred Marines and Navy personnel who would establish an airfield operations capability at what would become Henderson Field on Guadalcanal. Making multiple supply runs to Guadalcanal over the next days, the lightly armed converted World War I–vintage obsolescent destroyers relied on speed for survival. None of them would survive the war. Three of them wouldn’t survive the next three weeks.

USS Colhoun (APD-2) was bombed and sunk by 18 Japanese bombers while unloading off Guadalcanal on 30 August 1942, with the loss of 51 of her crew. USS Gregory (APD-3) and USS Little went down in a valiant but hopeless night fight against three Japanese destroyers just off Guadalcanal on 4–5 September 1942. Under the overall command of Commander Hugh W. Hadley, embarked on Little, as the two APDs turned to attack the Japanese destroyers that had just commenced shelling the Marines ashore, their slim chance of achieving surprise was accidently betrayed by flares dropped from a U.S. Navy PBY Catalina, which mistook the APDs for a Japanese submarine. The startled Japanese, who had failed to previously detect the APDs, shifted their fire from the Marines ashore. Five hundred Japanese shells later, the two APDs were on the bottom of Ironbottom Sound with almost 90 crewmen, including Hadley and the skippers of Gregory and Little. Their sacrifice prevented further shelling of the Marines that night.

As the Japanese destroyers exited the area and continued to fire on survivors in the water, Mess Attendant Second Class Charles J. French of Gregory rounded up 15 mostly dazed and wounded survivors and pushed them onto a raft. A strong swimmer, he then tied a rope around his waist and proceeded to tow the raft through shark-infested waters and away from Japanese-held shoreline on Guadalcanal, where capture would have meant torture and death, for eight hours—according to an officer survivor on the raft—before they were rescued after dawn.

Left out of most histories of the battle of Guadalcanal, this action (“Miscellaneous Action in the South Pacific” per Rear Admiral Samuel Eliot Morison) cost a similar number of Navy lives as Marines lost in the far more famous Battle of Bloody Ridge (approximately 90–100 killed in action) on Guadalcanal on 12–14 September. Rear Admiral Richmond K. Turner, commander of U.S. naval forces off Guadalcanal, wrote, “The officers and men serving in these ships have shown great courage and have performed outstanding service. They entered this dangerous area time after time, well knowing their ships stood little or no chance if they should be opposed by any surface or air force the enemy would send into those waters.” Yet, to support the Marines, they did.

Commander Hadley, Lieutenant Commander Harry F. Bauer (commanding officer of Gregory) and Lieutenant Commander Gus B. Lofberg (commanding officer of Little) were each awarded a posthumous Silver Star. Despite being recommended for a Navy Cross, French was awarded a Letter of Commendation signed by Admiral William F. Halsey.

The Epic Fight of USS Hugh W. Hadley (DD-774), 11 May 1945

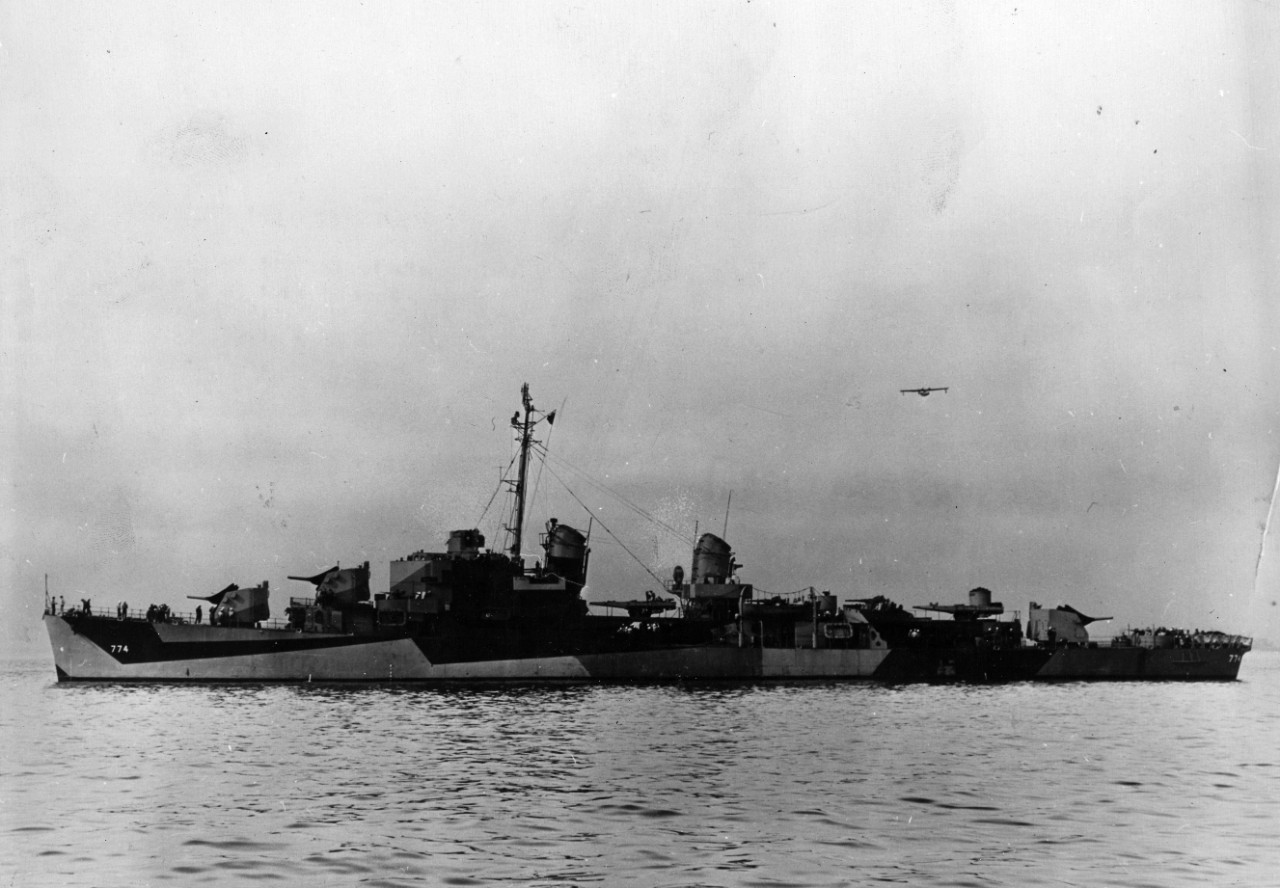

Following the loss of Colhoun, Little, and Gregory, and the deaths of Hadley, Lofberg, and Bauer, the Navy would name destroyers after all of them. USS Colhoun (DD-801) would be sunk by kamikazes off Okinawa on 6 April 1945, as would USS Little (DD-803) on 3 May. USS Harry F. Bauer (DD-738/DM-26) would later be damaged by a Japanese kamikaze off Okinawa on 6 June and would earn a Presidential Unit Citation. The Allen M. Sumner–class destroyer USS Hugh W. Hadley was commissioned on 25 November 1944 and would make history.

On 11 May 1945, Japanese massed kamikaze raid Kikusui No. 6 (“Floating Chrysanthemums”) of about 150 suicide aircraft resulted in another horrific day, which included the truly epic fight by destroyers Hugh W. Hadley and Evans (DD-552) at radar picket station RP15, north-northwest of Okinawa. Evans shot down 14 or 15 aircraft before she was put out of action by four kamikaze hits in quick succession. Hugh W. Hadley shot down 19 or 20 aircraft before she too was gravely damaged by a large bomb and three kamikaze hits. On both ships, the crews fought on and saved their ships, even when it seemed all hope was lost. Both ships were so badly damaged that neither was repaired. Hugh W. Hadley suffered 30 dead and 68 wounded, while Evans suffered 30 dead and 29 wounded (out of about 320 on each ship) in one of the most desperate battles against overwhelming odds in U.S. Navy history. Hugh W. Hadley’s tally was the highest number of aircraft shot down by a U.S. surface ship in a single engagement, and that of Evans was probably the second highest.

Vice Admiral Cooper’s RFI was followed up with, “Which U.S. Navy ship shot down the most aircraft with surface-to-air missiles, and has a ship ever shot down an anti-ship ballistic missile before now?” During the Vietnam War, USS Long Beach (CGN-9) shot down two, probably three, MiGs at long range with Talos missiles. USS Sterret (DLG-31) shot down one, possibly two, MiGs with Terrier missiles. USS Biddle (DLG-34) shot down two MiGs (one with Terrier missiles, one with guns), and USS Chicago (CG-11) shot down a MiG with Talos. No ship has previously shot down an anti-ship ballistic missile.

For more on TRANSDIV 12 and USS Hugh W. Hadley, please see attachments H-081-1 and H-081-2 (note that H-Gram 010 and H-Gram 046 previously covered these subjects). Previous H-grams may be found here. Further dissemination is greatly encouraged.