H-050-1: Naval Action in the Korean War, 25 June–1 September 1950

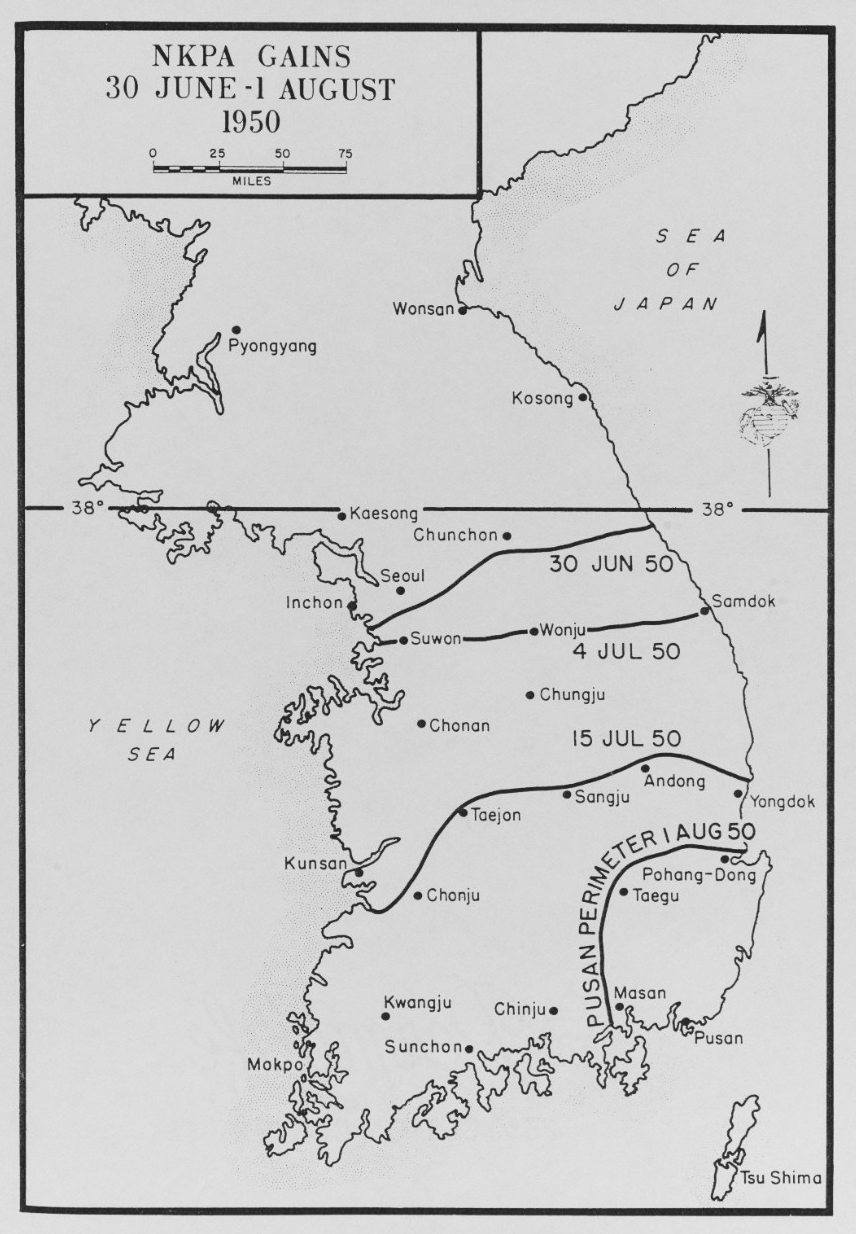

At 0400 on Sunday morning, 25 June 1950, in four main avenues of attack, an armored brigade and six divisions totaling 89,000 soldiers of the North Korean People’s Army (NKPA) poured across the 38th Parallel marking the boundary between the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (North Korea) and the Republic of Korea (South Korea). Spearheaded by about 200 Soviet-supplied T-34 tanks and 120 fighter and ground-attack aircraft, along with heavy artillery and with the advantage of tactical surprise, the North Koreans quickly routed the 38,000 Republic of Korea (ROK) troops in the forward area, who had no tanks, no anti-tank weapons, no air support, not much training, and no warning. The armored brigade and two NKPA infantry divisions (the 3rd and 4th Divisions), with two divisions in reserve, headed directly toward the ROK capital of Seoul, only 30 miles south of the 38th Parallel. The 6th and 1st NKPA Infantry Divisions attacked farther west before funneling into Seoul, while the 7th Infantry Division attacked through the central mountains and the 5th Infantry Division attacked southward on the highway along the ROK east coast on the Sea of Japan (East Sea to the Koreans).

Although there had been strategic intelligence warning that the withdrawal of U.S. troops from Korea in 1948 would risk a Communist North Korean attempt to reunify Korea by force, and there had been extensive warning of the North Korean build-up of strength and capability along the border, the exact timing of the attack still came as a surprise. By the end of the first day, ROK ground forces had been decimated and were in full retreat, and the South Korean air force (about half a dozen trainers and no combat aircraft) was of no use. The NKPA would be in the outskirts of the ROK capital of Seoul by early on 27 June.

The Battle of the Korea Strait, 26 June 1950

The lone bright spot in an overwhelmingly bleak situation on the first days of the attack was provided by the fledgling Republic of Korea Navy (ROKN). Before dawn on 26 June 1950, the most capable ship in the ROKN was underway from the main base at Chinhae and was on patrol about 18 miles from Pusan (now Busan) at the southeast tip of the Korean Peninsula, and sighted an unidentified ship in the darkness. The submarine chaser Bak Du San (PC-701), the former USS PC-823, challenged the unidentified steamer with signal lights, but received no response. Bak Du San then turned her searchlight on the steamer and received heavy machine-gun fire in return that killed the helmsman and seriously wounded the officer of the deck. Bak Du San then engaged the steamer with her single 3-inch gun and six 50-caliber machine guns.

The unidentified 1,000-ton steamer was actually a former U.S. transport that had been hijacked by South Korean Communist guerillas in October 1949 and taken to the North. On the night of 25–26 June 1950, the steamer was carrying 600 troops of the North Korean 766th Independent Infantry Regiment with the intent of seizing the port of Pusan. In a running gun battle at ranges of less than 400 yards, Bak Du San sank the steamer as she tried to flee, with the loss of almost all the North Korean troops on board. ROKN sailors used M-1 rifle fire against North Korean troops that tried to reach their vessel. Bak Du San suffered two dead and two wounded.

The “Battle of the Korea Strait,” as the ROKN would call it, had major strategic importance. At the time, the port of Pusan was very poorly defended. Had the North Korean surprise operation succeeded, the outcome of the war might have been very different, because by the beginning of August, Pusan was the last remaining port in South Korea that had not fallen to the North Koreans. It would be the only initial entry point for the U.S. forces that prevented the North Koreans from overrunning the entire Korean Peninsula.

Also on the previous morning of 25 June 1950, the ROKN had partial success interdicting one of two North Korean landings along the east coast of South Korea. The first North Korean convoy (two submarine chasers, one minesweeper, and 20 troop-carrying schooners) put ashore four battalions of NKPA troops near Kangnung, just far enough south of the 38th Parallel to cut off the retreat of ROK troops along the coast road. A second North Korean convoy (two minesweepers, one patrol ship, one submarine chaser, and several schooners) landed Communist guerillas near Samcheok (about halfway down the east coast of South Korea). The small ROKN minesweeper YMS-509 engaged the convoy and sank two schooners, but was forced to withdraw after a short battle with North Korean minesweeper No. 31.

At the start of the war, the ROKN was woefully under-funded, under-equipped, and under-trained, consisting of a few ex-U.S. and ex-Japanese vessels, including Bak Du San, 15 auxiliary motor minesweepers (mostly ex-Japanese), and one ex-U.S. landing tank ship tank (LST). Most of these had only recently been obtained. The ROKN counted about 7,000 personnel, including 1,200 ROK Marines. The ROKN “flagship,” Bak Du San, had been purchased in large part by taxing the salaries of all ROKN personnel, ROKN midshipmen selling scrap metal, and navy wives doing laundry. USS PC-823 had been decommissioned in early 1946, been transferred to the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy, and renamed Ensign Whitehead. The ship was in poor material condition when the ROKN bought her in September 1949 and then sailed her from New York to Korea via Hawaii (where a 3-inch gun was re-installed) and Guam (where the ROKN had just enough money to buy 100 rounds of 3-inch ammunition).

By contrast, the North Korean Navy was somewhat larger and better equipped than the ROKN, with 13,000 personnel, and equipment mostly obtained from the Soviet Union. This included three OD-200–type submarine chasers, five G-5–type aluminum-hulled motor torpedo boats (PT-boats), two former U.S. YMS-type small minesweepers (via U.S.-Soviet lend-lease during World War II), one ex-Japanese minesweeper, one floating base, one military transport, six various motor gunboats, and up to 100 miscellaneous small craft, schooners, junks, sampans, etc.

U.S. Navy Command Structure at the Start of the Korean War

The Secretary of the Navy was Francis P. Mathews, known derisively as “Rowboat” to senior naval officers as that was the extent of his Navy experience. A political fund raiser, Mathews had replaced John L. Sullivan when he resigned in protest over Secretary of Defense Louis Johnson’s unilateral decision to cancel the super-carrier United States (CVA-58). Johnson (also a fund raiser for President Truman, with service in the Army in World War I and Assistant Secretary of the Army in 1937–40) had no use for the Navy and made no effort to hide his disdain. Secretary Johnson had not even consulted or informed Secretary of the Navy Sullivan or Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Louis Denfeld before cancelling United States. Johnson’s primary mission was to drastically slash the defense budget and set himself up for his own presidential run.

Secretary Johnson believed the Navy was obsolete and was convinced by the new U.S. Air Force (established as a separate service by the National Security Act of 1947) that future wars would be fought and won by B-36 intercontinental bombers with nuclear bombs. “Rowboat” Mathews was Johnson’s hatchet man, and the two would be substantially responsible for the U.S. Navy’s abysmal state of readiness at the start of the Korean War. (If you wonder why many senior U.S. Navy officers weren’t exactly thrilled by naming an aircraft carrier Harry S. Truman—CVN-75—this is why, and, in another twist of irony, the original name for CVN-75 was the United States).

By 1949, due to drastic budget cuts after Truman was re-elected in 1948, the Navy had been drastically reduced in size. Of 24 Essex-class carriers built during World War II, only five were still operational (plus three Midway-class carriers) and, in 1949, Secretary Johnson directed that the number of operational carriers be reduced to four (which was the number the Army thought was adequate. The new U.S. Air Force argued that zero carriers was the right number). In addition, all but one battleship had been put into mothballs, along with numerous cruisers and destroyers. Perhaps even more importantly, the number of operational auxiliaries such as oilers had been severely reduced, significantly compromising the Navy’s ability to sustain itself at sea.

The Chief of Naval Operations was Admiral Forrest P. Sherman, at the time the youngest person to serve as CNO (until Admiral Elmo Zumwalt in 1970). He was commander of U.S. Navy Forces in the Mediterranean when he was called back to Washington in October 1949 to replace CNO Admiral Louis Denfeld. Denfield had been fired by Mathews in retribution for the “Revolt of the Admirals,” in which senior Navy leaders fought hard against the draconian budget cuts (which, if fully carried out, would have put every U.S. aircraft carrier into mothballs), as well as fighting against the U.S. Air Force nuclear bomber strategy (and losing badly in the court of U.S. public opinion). In 1949, a parade of admirals had testified before Congress about the crippling state of naval readiness, which undercut Secretary Mathews.

Forrest Sherman had been commanding officer of the carrier Wasp (CV-7) when she was torpedoed and sunk by a Japanese submarine in August 1942, and had been awarded a Navy Cross. He then served most of the war as deputy chief of staff to Admiral Nimitz, playing a critical role in the planning for the successful U.S. offensive across the Central Pacific. He would also be the youngest CNO to die in office, of a series of heart attacks at age 54 in July 1951.

Since 1948, the Commander-in-Chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet (CINCPACFLT) was Admiral Arthur W. Radford. Radford had been a highly accomplished carrier task group commander through most of the Pacific War and, despite being a vociferous opponent of the budget cuts and Air Force strategy and a leading figure in the “Revolt of the Admirals,” he somehow managed to keep his job. However, at the outbreak of the Korean War, the U.S. Seventh Fleet would be transferred to the operational control of the Commander, U.S. Naval Forces, Far East (COMNAVFE). COMNAVFE fell under the command of General of the Army Douglas MacArthur, who shortly thereafter became Supreme Commander of United Nations Forces in Korea (UNC Korea). As a result, Admiral Radford had no operational command role during the war. He would, however, become the second Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in 1953. At the commencement of hostilities, the U.S. Pacific Fleet had been reduced to only three operational Essex-class carriers, no battleships, and five heavy cruisers.

Since 1949, the Commander of U.S. Naval Forces Far East was Vice Admiral C. Turner Joy. Joy had been a key war planner and then commander of a cruiser division in 1944–45 against Japan. In the Far East, the mighty U.S. Navy armada that defeated in Japan had by June 1950 been reduced to the light anti-aircraft cruiser Juneau (CL-119), four destroyers, one submarine, ten minesweepers (several out-of-service—some things never change), land-based patrol squadrons, and one attached Royal Australian Navy frigate, all under the direct command of Vice Admiral Joy. Fortuitously, an amphibious task force of four ships was in Japanese waters for training and also fell under COMNAVFE.

The Commander of U.S. Seventh Fleet (C7F) was Vice Admiral Arthur D. Struble, who had command of key amphibious forces during World War II, including during the invasion of Normandy and then in the Western Pacific. Struble had a somewhat stronger force than Joy did, centered around the deployed aircraft carrier Valley Forge (CV-45), and including the heavy cruiser Rochester (CA-124), eight destroyers, and four submarines (one operating with COMNAVFE), operating from Subic Bay, Philippines.

At the outbreak of war, Struble was in Washington, DC. The senior commander in the Seventh Fleet was Rear Admiral John M. “Pegleg” Hoskins, Commander, Carrier Division THREE (CARDIV 3). He normally flew his flag on Valley Forge, then just getting underway from Hong Kong. Hoskins was in Subic Bay, the normal base for C7F, serving as acting commander of Seventh Fleet. Hoskins was a colorful and aggressive officer. He’d been the prospective commanding officer of the light carrier Princeton (CVL-23) and was aboard when she was hit by a Japanese bomb during the Battle of Leyte Gulf on 24 October 1944. He stayed aboard with the skeleton crew to help with damage control when the ship suffered a massive and fatal explosion of her own ordnance stores. Hoskins was awarded a Navy Cross, but had a foot blown off. He fought being discharged, stating, “The Navy doesn’t expect a man to think with his feet.” Upon recovery, he was given command of the new Essex-class carrier Princeton (CV-37), commissioned just after the end of the war.

Upon word of the North Korean attack, Hoskins immediately got the force underway from Hong Kong to return to Subic Bay to refuel, resupply, and link up with heavy cruiser Rochester (CA-124), with her nine 8-inch guns the largest U.S. surface combatant in the Western Pacific. By 27 June, “Task Force 77” was already underway heading north toward Korea.

Evacuation of Seoul, 26 June 1950

With the stunningly rapid North Korean advance, the U.S. ambassador to Korea, John J. Muccio, requested an immediate evacuation of U.S. nationals from the South Korean capital of Seoul. COMNAVFE quickly responded and, on 26 June 1950, the destroyers Mansfield (DD-728) and De Haven (DD-727) arrived at Inchon to escort the Norwegian-flag ship Reinholt, with 700 U.S. and friendly foreign nationals embarked, which departed Inchon at 1630. De Haven remained behind to escort a Panamanian freighter with additional evacuees on board. Air cover for the seaborne evacuation was provided by U.S. Air Force fighters flying from airfields that would shortly be overrun by NKPA troops. North Korean La-7 fighters and Il-10 ground-attack aircraft were very aggressive in the opening days of the war, and destroyed a U.S. Air Force C-54 transport aircraft on the ground. Nevertheless, about 750 U.S. citizens and friendly foreign nationals got out by air on 27 June, and another 850 on 28 June.

Air Force fighters, including F-80 Shooting Star straight-wing jets, defended the transport flights and fought off attacking North Korean aircraft. An F-82 Twin Mustang (basically two P-51 fighters welded at the wing, with a pilot in one and a radar operator in the other), scored the first air-to-air kill of the war. On 27 June, six U.S. fighters shot down seven North Korean aircraft over Kimpo airfield, ROK (which fell the next day to NKPA troops). On 28 June, North Korean Yak-9 fighters strafed Suwon airfield, destroying one B-26 bomber and one F-82 Twin Mustang fighter. Twenty B-26 bombers then bombed railroad yards and lines between the 38th parallel and Seoul; one badly damaged B-26 crashed on landing, killing all aboard. Additional North Korean aircraft were shot down. The high proportion of losses being suffered the North Korean air force caused it to be more circumspect, at least until the introduction of Chinese-based, Russian-piloted Mig-15 swept-wing jet fighters in November 1950. However, within a couple days, U.S. Air Force operations would be limited to a couple of inadequate fields in the vicinity of Pusan and to bases in Japan, which allowed only very limited time on station over Korea due to the extended range.

On 27 June 1950, Seoul fell to the advancing North Korean Army, the first of four times it would change hands during the war, at great suffering to the civilian population. The North Koreans would execute over 200,000 citizens of Seoul and take another 80,000 north. On the other hand, the South Koreans blew the bridge over the Han River while 4,000 South Korean refugees were still on it, killing many hundreds and trapping tens of thousands more on the north bank. Hundreds of thousands of Korean civilians were killed during the war. There were cases of civilian refugees being killed by both sides. The NKPA would use civilian refugees as human shields, and many were killed in the crossfire or by U.S. forces not willing to take the chance that enemy combatants might be intermingled with refugees. The South Korean government, headed by President Syngman Rhee, evacuated first to Taegu and then to Pusan. (Rhee would remain as president of South Korea until 1960, leading a strongly authoritarian government.)

Also on 27 June, six of the nine Martin PBM-5 Mariner flying boats of Patrol Squadron 47 (VP-47) based in Subic Bay moved to Japan and commenced patrols around the Korean Peninsula.

Initial United Nations and U.S. Actions, June 1950

On 25 June 1950, the United Nations Security Council issued a resolution (UNSCR 82) condemning the North Korean invasion. On 27 June, the UN Security Council proclaimed the North Korean invasion a breach of world peace and requested member nations assist the South Koreans (UNSCR 83). At the time, the Soviet Union was boycotting the Security Council and therefore was not present to veto the resolution, a mistake they would never make again. The Soviet boycott was over whether the Communist government in China, which had just won the Chinese civil war in 1949, or the Nationalist Chinese government, which had taken refuge on the island of Formosa, should have China’s UN Security Council seat.

At the time, the Cold War between the Soviet Union and the Western Allies was well underway. The Soviets had detonated an atomic bomb in August 1949 (thanks in part to Soviet spies in the U.S. program) and the “Iron Curtain” had divided Communist Eastern Europe (under Soviet occupation/domination) and free Western Europe. The Soviets had blockaded West Berlin from June 1948 to May 1949, resulting in the Berlin airlift. Soviet reaction to U.S. Navy reconnaissance flights around the periphery of the Soviet Union had become increasingly hostile. On 8 April 1950, Soviet aircraft shot down a PB4Y-2 Privateer (BuNo 59645) of VP-26 Det A at NAS Point Lyautey, Morocco, flying from Wiesbaden, West Germany, over the Baltic Sea off Liepaja, Latvia, killing all 10 aboard (see H-Gram 029/H-029-3).

The (woefully underfunded) U.S. defense strategy at the time was based on the Truman Doctrine of “Containment” of the Soviet Union and Communist allies, such as the newly victorious People’s Republic of China. Under the Truman Doctrine, laid out in 1947, the U.S. would not attempt to invade or overthrow the Soviet Union (at least by force), but would resist any further expansion by the Soviets. The strategy was based on the assumption that Europe was the primary theater of operations, and U.S. force structure and deployments were focused almost exclusively on deterring or defeating further Soviet aggression in Europe, while aiding countries engaged in anti-Communist insurgencies, such as Greece. The Truman administration had long since given up on trying to keep China from falling to the Communists. The last thing the U.S. wanted was a war in the Far East, which would divert resources from the European “main effort.”

Korea had been under Chinese influence for centuries, but in the late 1800s an increasingly powerful Japan encroached on Korean sovereignty (resulting in the Sino-Japanese War of 1894, which China lost badly). Following the Russo-Japanese War in 1905, Japan expanded their influence farther into Korea until the Japanese took over Korea as a colony in 1910 and ruled it with a ruthless hand. When the Soviets entered the war against Japan in August 1945, Soviet forces overran Manchuria and parts of Korea. Although the Allied Cairo Conference in 1943 stated Korea should be independent and united, the reality was that the northern half was under Soviet occupation and the southern under U.S. occupation.

By 1948, two separate Korean governments had come to be: a Soviet-supported Communist government in the more industrialized North, led by Kim Il-sung (grandfather of current North Korean “Dear Leader” Kim Jong-un), and the more agrarian Republic of Korea in the south, led by President Syngman Rhee (who was quite ruthless about remaining president). Unlike the Soviets, the United States couldn’t wait to get out of Korea and all but a couple hundred U.S. troops were withdrawn by the end of 1948 despite an increasing Communist insurgency in the South. This also created the opening Kim Il-sung had been looking for to reunify the Korean Peninsula, by force, under Communist rule.

How much Soviet dictator Josef Stalin knew and approved of Kim Il-sung’s plan has been hotly debated over the years. More recent information suggests that although the exact timing may have caught him by surprise, he knew and approved of the plan in advance, with the goal of getting the United States bogged down in a land war in Asia (which was exactly what U.S. leaders feared when the war broke out). There is also evidence that Stalin was cynically willing to give North Korea aid, but not enough for them to win quickly.

The North Korean invasion threw U.S. defense planning out the window. The United States was concerned that the invasion was a Soviet ploy to divert U.S. attention from possible major Soviet action in Europe. The United States was not interested in getting into a nuclear war with the Soviets, especially over South Korea. There wasn’t even a defense treaty between the United States and the ROK. In a famous January 1950 speech, U.S. Secretary of State Dean Acheson had failed to include South Korea (or Taiwan for that matter) within the “defense perimeter” of vital U.S. interests, which probably gave Kim Il-sung even more encouragement that he could get away with an invasion.

Nevertheless, the North Korean aggression was so blatant and, mindful of the lessons of appeasement of the Nazis before World War II, President Truman quickly made the decision that the North Korean invasion must be stopped, especially if the new United Nations was to be something more than the previously ineffective League of Nations. The trick was to stop the invasion without getting into an all-out war with the Soviets. One thing quickly became apparent: B-36 intercontinental bombers armed with atomic bombs were useless for this situation. Suddenly, the Truman administration discovered it needed the Navy, and it was aircraft carriers and amphibious warfare capability to the rescue (although sadly short of critical ammunition and supplies).

Upon the passage of UNSCR 83, Truman ordered U.S. Navy and Air Force to support the ROK. He also ordered the Seventh Fleet to take steps to prevent a Communist Chinese invasion of Formosa. As a result of this order, Task Force 77, with carrier Valley Forge, steamed through the Formosa (Taiwain) Strait on 27–28 June and put on an air power demonstration intended to deter the Communist Chinese and reassure the Nationalist Chinese. Lack of People’s Republic of China (PRC) amphibious lift and inadequate air and navy support probably had more to do with PRC restraint, although Chinese Premier Chou en-Lai complained loudly about the U.S. Navy action. The large number of junks gathered on the PRC side of the Formosa Strait suggested the PRC was at least thinking about invading Taiwan. Throughout the conflict in Korea, the United States did not want another conflict to break out between the PRC and Nationalist China, so Seventh Fleet ships would patrol the Formosa Strait with the intent to keep both sides from going at it. The United States even refused Nationalist Chinese offers of troops to fight in Korea lest the action provoke the PRC into starting another fight Americans didn’t need or want.

On 27 June, the operational control of C7F changed from CINCPACFLT to COMNAVFE, under Commander-in-Chief U.S. Forces Far East (CINCFE), General of the Army Douglas MacArthur.

On 28 June, the British Admiralty placed Royal Navy units in the Far East at the service of COMNAVFE. Under the command of Rear Admiral Sir William G. Andrewes, RN, this force included the aircraft carrier HMS Triumph (R-16), two light cruisers (HMS Belfast and HMS Jamaica), two destroyers, and two frigates. One Australian destroyer and one frigate added to the “Commonwealth” Force. COMNAVFE requested these forces rendezvous with C7F and TF 77 at Buckner Bay, Okinawa, as Sasebo, Japan, was considered potentially at risk from Soviet or Chinese attack.

USS Valley Forge (CV-45), initially only U.S. carrier in Asian waters at the beginning of the Korean War, and USS Leyte (CV-32) are shown moored at Sasebo, Japan, circa October/November 1950. USS Hector (AR-7) is moored beyond the two carriers, with other U.S. and British warships in the distance (80-G-426270).

HMS Triumph, which operated with USS Valley Forge (CV-45) off of Korea during the summer of 1950, is shown underway off Subic Bay, Philippines, during combined U.S.-British naval exercises, 8 March 1950. Planes on her deck include Supermarine Seafire 47s, forward, and Fairey Fireflys aft (NH 97010).

Initial U.S. Navy Combat at Sea, Early July 1950

The light cruiser Juneau, commanded by Captain Jesse Clyborn Sowell, had arrived in Japan on 1 June 1950, and was the flagship for Commander, Cruiser Division FIVE (CRUDIV 5), Rear Admiral John M. Higgins. Higgins had been awarded a Navy Cross as Commander, Destroyer Division 23, embarked on destroyer Gwin (DD-433), when she was torpedoed and subsequently scuttled during the Battle of Kolombangara on 13 July 1943. Juneau was patrolling in the Tsushima Strait when the war broke out, ironically guarding against Korean pirates.

Juneau was the most capable ship immediately available to COMNAVFE, and Higgins was designated Commander, Task Group 96.5. Initially dispatching the destroyers Mansfield and De Haven to cover the evacuation from Seoul, Higgins took Juneau into the Sea of Japan on 28 June and, the next day, she bombarded North Korean troop concentrations at Bokuku Ko, the first of countless U.S. shore bombardments during the war. Juneau subsequently bombarded bridges and railroads, significantly impeding the North Korean advance down the east coast of South Korea (actions that would earn Rear Admiral Higgins a Navy Distinguished Service Medal).

However, on 29 June, Juneau’s radar detected two groups of surface ships moving down the east coast of South Korea. Juneau had been informed that ROKN units had already moved south and so she opened fire. One vessel was sunk and the others dispersed. Regrettably, the target was the ROKN (ex-Japanese) minelayer JML-305. In the rampant confusion of the time, this led to rumors that a Russian cruiser had been sighted off the east coast of Korea.

Air Strikes on North Korea and Commitment of U.S. Ground Troops Ordered, 29–30 June 1950

At first, President Truman was reluctant to authorize air strikes into North Korea or to introduce U.S. ground troops into Korea for fear of getting into a major war with the Soviet Union that might expand to the European Theater. He quickly changed his mind, however, as the debacle only grew worse. On 29 June, 18 USAF B-26s bombed Heijo airfield near the North Korean capital of Pyongyang, destroying about 25 aircraft on the ground (this put a serious crimp in the North Korean air force). U.S. Air Force fighters shot down five more North Korean fighters, and gunners on a B-29 four-engine bomber shot down another.

On 30 June, President Truman authorized General MacArthur to commit ground troops to Korea and ordered the U.S. Navy to establish a blockade of the entire Korean peninsula. He was somewhat chagrined to discover that because of the massive force structure drawdowns, the Navy really didn’t have the capability to do so, but the service would do the best it could.

Carrier Task Force 77 Underway for Combat, 1 July 1950

Following orders issued by COMNAVFE, TF-77 departed Buckner Bay, Okinawa, on 1 July. Carriers Valley Forge and HMS Triumph headed for the Yellow Sea to conduct strikes into North Korea from the west, scheduled for 3 July.

Valley Forge, known to her crew as the “Happy Valley,” was one of 24 Essex-class carriers built during World War II, but was not commissioned until November 1946. With less wear and tear than the combat carriers of the war, she was not placed into reserve as many of the other ships were. Valley Forge was the first carrier to deploy with jet aircraft. Her 86-plane air group (Carrier Air Group FIVE, CVG-5) included two jet fighter squadrons, VF-51 and VF-52, both equipped with the F9F-2/3 Panther straight-wing jet fighters (30 total). VF-51 (under an earlier designation, VF-5A) was the first U.S. Navy squadron to qualify for carrier operations in jets, which was exceedingly dangerous before the advent of angled decks and other modifications in the mid-1950s. CVG-5 also included two squadrons of F4U-4B Corsair fighter-bombers, VF-53 and VF-54, and one squadron (VA-55) of 14 of the newer AD-4 Skyraider piston-engine bombers, also known as “dump trucks” for the prodigious ordnance load they could carry.

Like the United States, British carrier presence in the Far East had been reduced to one by the outbreak of the Korean War. HMS Triumph was approaching Hong Kong when she received orders to join with TF-77 at Buckner Bay. Triumph had an air group of about 48 aircraft. These included Supermarine FR.47 Seafire (the navalized version of the famous Spitfire) fighters of 827 Squadron, and Fairey FR.1 Firefly fighter-bomber/ASW aircraft of 800 Squadron, also of World War II vintage.

U.S. Ground Troops from Japan Head to Korea, 1 July 1950.

Also on 1 July, the lead elements of the U.S. 24th Infantry Division were airlifted into South Korea, and other elements followed by sea, some in Japanese-manned LSTs and many others in hastily chartered Japanese shipping. Softened by years of garrison duty in Japan, the 24th Infantry Division was under-manned, under-equipped, and under-trained. However, it was the division stationed in closest proximity to Korea. Nevertheless, the commitment of a force that was not ready for war would be an utter disaster. The 25th Infantry Division would follow afterward, also mostly in chartered shipping, which also resulted in massive congestion in Pusan harbor.

Meanwhile, CINCPACFLT established Task Force Yoke, commanded by Rear Admiral Walter Boone, to scrounge up every operational ship on the U.S. West Coast to prepare for immediate deployment to the Far East.

The Battle of Chumonchin Chan, 2 July 1950

The British light cruiser HMS Jamaica (four triple 6-inch gun turrets) and the sloop (frigate) HMS Black Swan (three twin 4-inch gun turrets) were transiting from Hong Kong to Japan when the North Korean invasion commenced. The two ships were ordered to join up with Rear Admiral Higgins and Juneau in the Sea of Japan. (Jamaica was a veteran ship that had put torpedoes into the German battlecruiser Scharnhorst off Norway’s North Cape in December 1943. The torpedoes had finished off the German ship after it had been pummeled by gunfire from both Jamaica and the battleship HMS Duke Of York.) Black Swan had completed repairs to her superstructure after being hit by Communist Chinese gunfire on the Yangtze River in the midst of the Chinese Civil War in April 1949. She had suffered seven wounded while attempting unsuccessfully to go to the rescue of her sister ship, HMS Amethyst, which had run aground in the river and was being hit by Communist artillery. (Amethyst escaped in July after suffering 22 killed and 31 wounded. The other ships in the rescue force were hit worse than Black Swan. Heavy cruiser HMS London suffered 15 dead and 13 wounded, and destroyer HMS Consort suffered 10 killed and 23 wounded).

On 2 June 1950, Juneau, Jamaica, and Black Swan were operating off the east coast of South Korea, not far south of the 38th Parallel, preparing to bombard NKPA ground forces moving south. At 0615, Black Swan sighted a North Korean convoy that had delivered ammunition and was already heading north. The convoy consisted of 10 motor trawlers used to transport ammunition, escorted by four torpedo boats and two motor gunboats.

As the UN force closed to engage, the North Korean PT-boats turned to attack and charged. The cruisers opened fire at 11,000 yards and, by the time the range closed to 4,000 yards, PT No. 24 was already sunk, PT No. 22 was dead in the water, PT No. 23 was trying to reach the beach, and PT No. 21 was fleeing northward. When the engagement was over, three of the four PT-boats and both motor gunboats had been sunk. Jamaica took two North Koreans prisoner. The UN force suffered no casualties. North Korean casualties are unknown, but included most of the crews of the five sunken boats. The 10 ammunition trawlers escaped, but were later hunted down and destroyed by Juneau some days later. North Korean propaganda claimed that their heroic PT-boats sank the heavy cruiser Baltimore (CA-68). At the time, Baltimore was decommissioned in reserve at Bremerton, and wasn’t re-commissioned until November 1951.

The “Battle of Chumonchin Chan” would be the first, and last, surface engagement between U.S. ships and North Korean navy vessels, as the North Koreans deemed it inadvisable to challenge UN supremacy at sea again. What remained of the North Korean navy would ultimately seek refuge in Soviet and Chinese ports. However, there would be multiple surface actions between ROKN forces (which were beefed up with the provision of three more submarine chasers in mid-July) and North Korean small craft attempting to infiltrate ammunition, supplies, and troops behind UN lines.

Also on 2 July, the ROKN Naval Base Detachment at Pohang (on the southeast coast of South Korea, north of Pusan) detected and wiped out a North Korean infiltration landing. The next day, on the southwest side of South Korea near Chulpo (south of Inchon), the ROKN minesweeper YMS-513 detected and destroyed three North Korean supply craft. Despite its small size, the ROKN would gain a reputation as the most aggressive and effective South Korean service in the first year of the war (although to be fair, there was no separate ROK Marine Corps and not much of an air force yet).

At 2020 on 3 July, two North Korean ground attack aircraft (probably Il-10s) came out of the haze overland and attacked Black Swan, causing some minor structural damage before escaping without being hit. There had been intelligence warning that an air attack was possible. This was the first North Korean air attack on ships. Such attacks would actually be very rare, as TF 77 aircraft surprised the North Korean Air Force right in their home bases the next day.

USS Juneau (CLAA-119) receives ammunition and fuel at Sasebo, Japan, on 6 July 1950. Flagship of Rear Admiral John M. Higgins, Commander, Task Group 96.5, Juneau actively patrolled and bombarded along the Korean east coast from 28 June to 5 July 1950. She was the first U.S. Navy cruiser to see combat action during the Korean War. Note Japanese floating crane alongside 80-G-417996).

First Navy Air Strikes, 3 July 1950

In the early morning of 3 July 1950, while operating in the Yellow Sea, HMS Triumph launched 12 Firefly fighter-bombers and nine Seafire fighters armed with rockets to attack the North Korean airfield at Haeju, 65 miles south of Pyongyang. Shortly thereafter, Valley Forge launched 16 Corsairs and 12 Skyraiders for a strike on airfields and other targets in and around Pyongyang. Last to launch were eight Panther jet fighters, which—due to their significantly greater speed—arrived over the targets before the Corsair/Skyraider strike. This would mark the first combat employment of the Panther and Skyraider.

As two VF-51 Panthers were conducting a second strafing pass on Pongyang airfield (North Korean anti-aircraft fire was pretty ineffective at that stage), a North Korean Yak-9 fighter (somewhat like a P-51 Mustang) rolled out of a hanger and got airborne, followed closely by a second. Lieutenant (j.g.) Leonard H. Plog rolled in on the second Yak-9 first and blew off its wing with a short burst 20-mm fire. Plog had been an SB2C Helldiver dive-bomber pilot in VB-83 on ESSEX (CV-9) late in World War II, and thus became the first Navy pilot to shoot down a plane in the Korean War—and the first Navy jet pilot to achieve an air-to-air kill. A few moments later, Ensign Elton W. Brown shot down the other Yak-9. Other Panthers destroyed three more aircraft on the ground, while the Corsairs and Skyraiders blew up hangars, fuel storage tanks, and other airfield facilities, and cratered the runway, while also damaging a nearby rail yard.

That afternoon, Valley Forge aircraft hit Pyongyang again, this time targeting railroads, roads, and bridges. Air attacks from the carriers continued on 4 July, inflicting significant damage on North Korean locomotives and rail facilities. A Skyraider dropped a span on the Taedong River Bridge (the major river that runs through Pyongyang). Four Skyraiders were hit and damaged by ground fire. One of the Skyraiders was unable to lower flaps while attempting to recover on Valley Forge and bounced over the barricade into the planes parked forward. The Skyraider was wrecked and two Corsairs destroyed, with other aircraft damaged to lesser degrees.

The carriers then moved to the south in the Yellow Sea and air strikes focused on North Korean troop movements and concentrations in South Korea. Initially, North Korean troops moved down South Korean roads in daylight in tightly packed formations, advancing very quickly. U.S. Navy carrier aircraft and Air Force aircraft from Japan initially inflicted very heavy casualties on North Korean troops (and tanks), but without appreciably slowing their advance. Eventually, however, the high losses drove the North Koreans to hide in the day and move at night, but that didn’t come until later.

Task Force Smith Debacle, 5 July 1950

On 5 July 1950, the lead element of the U.S. 24th Infantry Division, a battalion-sized force designated “Task Force Smith,” attempted to block the North Korean advance near Osan, in the first clash between the U.S. Army and the NKPA. The 540 U.S. troops had no weapons that could stop the 36 North Korean T-34 tanks that smashed through the U.S. defensive line as the U.S. force was quickly flanked by the overwhelming numbers (about 5,000) of North Korean troops. Of the U.S. force, 60 men were killed, 82 captured, and 21 wounded, and the remainder barely escaped. In the early days of the war, there were also multiple instances of North Koreans executing captured American soldiers.

Although the numbers made a big difference, the NKPA also proved to be better trained, disciplined, and equipped, and actually suffered fewer casualties than Task Force Smith. In some cases, U.S. discipline broke down and U.S. troops abandoned positions, equipment, and wounded to the enemy. Task Force Smith would be studied for years at war colleges as an example what happens when a force is not ready for war. Other elements of the 24th Infantry Division would attempt several times to slow the North Korean advance in the next days, with the same result as Task Force Smith, only with even worse casualties.

Other Actions, Early to Mid-July 1950

On 5 July 1950, COMNAVFE issued OpOrder 50 to implement President Truman’s order for a blockade of the Korean Peninsula.

On 6 July, PBM-5 Mariner flying boats of VP-46 arrived from San Diego at Buckner Bay, Okinawa, tended by Suisun (AVP-53). The Mariners commenced patrols along the China Coast. By 18 July, Suisun and the Mariners moved to the Penghu Islands, right in the Formosa Strait. Meanwhile, on 8 July, nine Japan-deployed P2V-3 Neptune maritime patrol aircraft of VP-6 commenced reconnaissance operations along the east coast of Korea. Nine VP-28 Consolidated PB4Y-2 Privateers (the Navy version of the B-24 four-engine bomber) deployed to Okinawa on 16 July and commenced reconnaissance operations along the China coast.

On 7 July, the United Nations Security Council designated General of the Army Douglas MacArthur as Supreme Commander of United Nations Forces in Korea. This gave General MacArthur operational control of all Allied forces, including those of the Republic of Korea, and by extension, Vice Admiral C. Turner Joy had operational control of Allied navies, including the ROKN.

On 8 July, HMS Jamaica was bombarding shore targets on the east coast of South Korea when she was hit by fire from a North Korean 76-mm gun, which killed six British sailors. Nevertheless, the ship remained operational and continued to bombard targets. By this time, Jamaica and Black Swan had been joined by frigates HMS Alacrity and HMS Hart, and formed the British component of the East Korean Support Group (CTG 96.5) in the Sea of Japan. CTG 96.5 attempted to impede the advance of the NKPA 5th Infantry Division down the coast, with some degree of success.

Commander Michael J. L. Luosey and the ROKN

At the outbreak of the war, the Chief of Naval Operations of the ROKN, Admiral Sohn Won-Il, was in Hawaii to take delivery of three former U.S. Navy submarine chasers. Vice Admiral Joy appointed newly arrived Commander Michael J. Lousey as Deputy Commander, Naval Forces Far East, and directed him to take operational control of the ROKN under UN authority. Luosey was a 1933 graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy and had been an instructor at the Naval Academy in the first half of World War II. He then commanded destroyers Sproston (DD-577) from 1943 to 1945, earning two Bronze Stars with Combat V, and then Bordelon (DD-881) from 1945 to 1947. As the United States was leader of the United Nations force, other Allied forces fell under U.S. operational control, so Admiral Sohn remained CNO, but operational direction of the ROKN would come from Commander Luosey under UN (U.S). authority. Arriving in Pusan with a staff of one lieutenant and five enlisted sailors, Luosey assumed operational control of the ROKN on 9 July. During the next year and a half, Luosey would earn the Navy Distinguished Service Medal and two Legion of Merits for his extraordinary efforts.

The first ROKN operation under Luosey’s direction was for a ROKN LST to take 600 ROK Marines to Kunsan on the southwest coast of South Korea and landing there on 15 July in an attempt to hold the port. However, because of the overwhelming NKPA force moving down the west coast, the Marines were just as quickly withdrawn by the LST on 19 July. On 17 July, Admiral Sohn arrived with the three newly acquired submarine chasers (PC-702, -703, and -704) and ROKN capability was significantly increased. The ROKN would repeatedly engage North Korean craft in coastal waters trying to bring in ammunition and supplies or infiltrate troops. As the roads became increasingly lethal to NKPA troop and logistics movement due to U.S. Navy and Air Force air strikes, the North Koreans would step up efforts to bring in supplies via small craft along the coast, which would culminate in August 1950 as they made their major push to capture the entire Korean Peninsula.

Navy Distinguished Service Medal citation for Captain Luosey:

The President of the United States of America takes pleasure in presenting the Navy Distinguished Service Medal to Captain (then Commander) Michael Joseph Luosey, United States Navy, for exceptionally meritorious and distinguished service in a position of great responsibility to the Government of the United States as Commander Fleet Activities Pusan from 3 November 1950 to 31 December 1950; and as Commander of all Republic of Korea Naval Forces assigned to the United Nations Blockading and Escort Force (Commander Task Group NINETY-FIVE POINT SEVEN), from 3 November 1950 to June 1952, during operations against enemy aggressor forces in Korea. With Pusan the only base in Korea for logistic support of naval units and the sole point of entry for the ever-increasing supply of all troops, munitions and equipment, Captain Luosey was eminently successful in establishing and operating Fleet Activities and met all requests for assistance with marked efficiency, sound judgment and resourceful ingenuity. As the first United States Navy representative in Korea during the period when all friendly forces were being slowly forced southward to the alarmingly short perimeter around Pusan, he labored untiringly to sustain liaison with top military commanders on questions of immediate and far reaching importance which were contributing factors in maintaining the security of this vital port. Charged with the responsibility for the operation, training and administration of all Republic of Korea naval units over a period of almost two years, Captain Luosey instilled a high degree of esprit de corps and fighting spirit in the personnel under his command and ably welded these forces into effective combat groups which later achieved major successes in blockading, minesweeping and patrol activities. His inspiring leadership, outstanding professional skill and steadfast devotion to duty throughout reflect the highest credit on Captain Luosey and the United States Naval Service.

First UN Landing in North Korea, 11–12 July 1950

On 10 July, Juneau and destroyer Mansfield steamed north in the Sea of Japan to put a demolition party ashore in North Korea. Its mission was to blow up a key railroad tunnel between Tanchon and Songjin on the northeast coast of South Korea. Doing so would cut the rail line from Vladivostok, Soviet Union, necessitating that further Soviet supplies take the much longer way around through Manchuria. Led by the executive officer of Juneau, Commander William B. Porter, the party included a lieutenant, four enlisted Marines, and four gunner’s mates. At midnight on 11–12 July, Mansfield pulled within 1,000 yards of the North Korean coast. The demolition party went ashore in a motor whaleboat. Other than dealing with cliff-like terrain, the infiltration went well and two 60-pound explosive charges were placed in the tunnel, rigged to detonate with the passage of the next train. Commander Porter and his party thus became the first U.S. military personnel to “invade” North Korea. Porter was awarded a Legion of Merit with Combat V for leading the operation.

U.S. Navy Command Actions, Mid-July 1950

By mid July, the UN naval command structure was fairly well solidified. Vice Admiral Joy was both Commander Naval Forces Far East (COMNAVFE) and Commander Task Force 96 (CTF 96). Task Group 96.5 was designated the East Korea Support Group, commanded by Rear Admiral Higgins, and comprised of U.S. Navy ships blockading and bombarding the east coast of Korea. TG 96.8 was designated the West Korea Support Group, commanded by Rear Admiral Andrewes, RN, and comprised of Commonwealth and international ships blockading and bombarding the west coast of Korea. TG 96.6 was the minesweeping group; TG 96.7 was the ROKN; TG 96.8 was the escort carrier group; and TG 96.9 was the submarine group. TG 96.3 consisted of 15 Japanese-manned LSTs and other Japanese manned-transports (termed SCAJAP), which were under the operational control of the U.S. Occupation Force in Japan prior to being shifted to COMNAVFE after the outbreak of war.

Vice Admiral Struble, the commander of Seventh Fleet, was also commander of Task Force 77, and for Korean operations was subordinate to COMNAVFE. The major components of TF 77 included Carrier Task Group 77.2/Carrier Division THREE, commanded by Rear Admiral Hoskins; Task Group 77.4, consisting of eight destroyers, commanded by Captain C. W. Parker; and Task Group 77.5, the British carrier group. One of Struble’s challenges was that the Formosa Straits patrol, for which he was responsible, fell under CINCPACFLT, not COMNAVFE, which placed multiple demands on limited assets.

In mid-July, an additional COMNAVFE reorganization took place. All blockade ships were placed in Task Group 96.5, commanded by Rear Admiral Charles C. Hartman. The East Coast Support Group was split into two alternating elements, CTE 96.51 and CTE 96.52. Rear Admiral Andrewes remained in command of the West Coast Support Group, re-designated to CTE 96.53. An additional element was formed: the Escort Element, designated CTE 96.50.

Task Force 90, the Amphibious Force Far East, commanded by Rear Admiral James H. Doyle, consisted of the amphibious command ship Mount McKinley (AGC-7), attack transport Cavalier (APA-37), attack cargo ship Union (AKA-106), LST-611, and fleet tug Arikara (ATF-98).

Additional international ships had been arriving to participate in the UN operation. By mid-July, Rear Admiral Andrewes had under his command for Yellow Sea operations the light cruisers HMS Jamaica, HMS Kenya, and HMS Belfast, and destroyers HMS Cossack, HMS Cockade, HMS Charity, the Australian destroyer HMAS Bataan, and the Netherlands destroyer HNLMS Evertsen. This force was bolstered further in late July with the arrival of three Canadian destroyers, HMCS Cayuga, HMCS Athabaskan, and HMCS Sioux. On 1 August, a French frigate and two New Zealand frigates, HMNZS Tutira and HMNZS Pukaki, joined the UN force.

On 10 July, COMNAVFE directed that the naval blockade be extended to the North Korean ports of Wonsan and Chinnampo, on the east coast of North Korea. To this point, the blockade had only covered ROK ports captured by the North Koreans. The CNO directed CINCPACFLT to sail Task Force Yoke when ready, which would significantly augment U.S. naval forces in the Korean and Formosa operating areas.

On 11 July, the first intelligence reports came in of North Korean defensive minelaying at the North Korean east coast port of Chongjin. Extensive North Korean minelaying activity in their waters would significantly complicate future operations and would account for all five U.S. ship losses during the war (four minesweepers and a fleet tug) and the most significant damage to other ships. Also on 11 July, the CNO authorized the activation of the Reserve Fleet (which was where the vast majority of U.S. Navy ships were in 1950 due to the drastic budget cuts).

On 12 July, COMNAVFE established Naval Air Japan in Tokyo with an interim staff under the command of Rear Admiral George R. Henderson to provide direction to the expanding naval aviation forces in the Far East. On 9 August, this organization would be re-designated as Fleet Air Japan. Henderson had been executive officer of Hornet (CV-8) during the Doolittle Raid, then commanding officer of the light carrier Princeton (CVL-23), and the commander of a division of escort carriers toward the end of the war. He would subsequently serve as Carrier Division FIVE and Task Force 77 commander in May–August 1951.

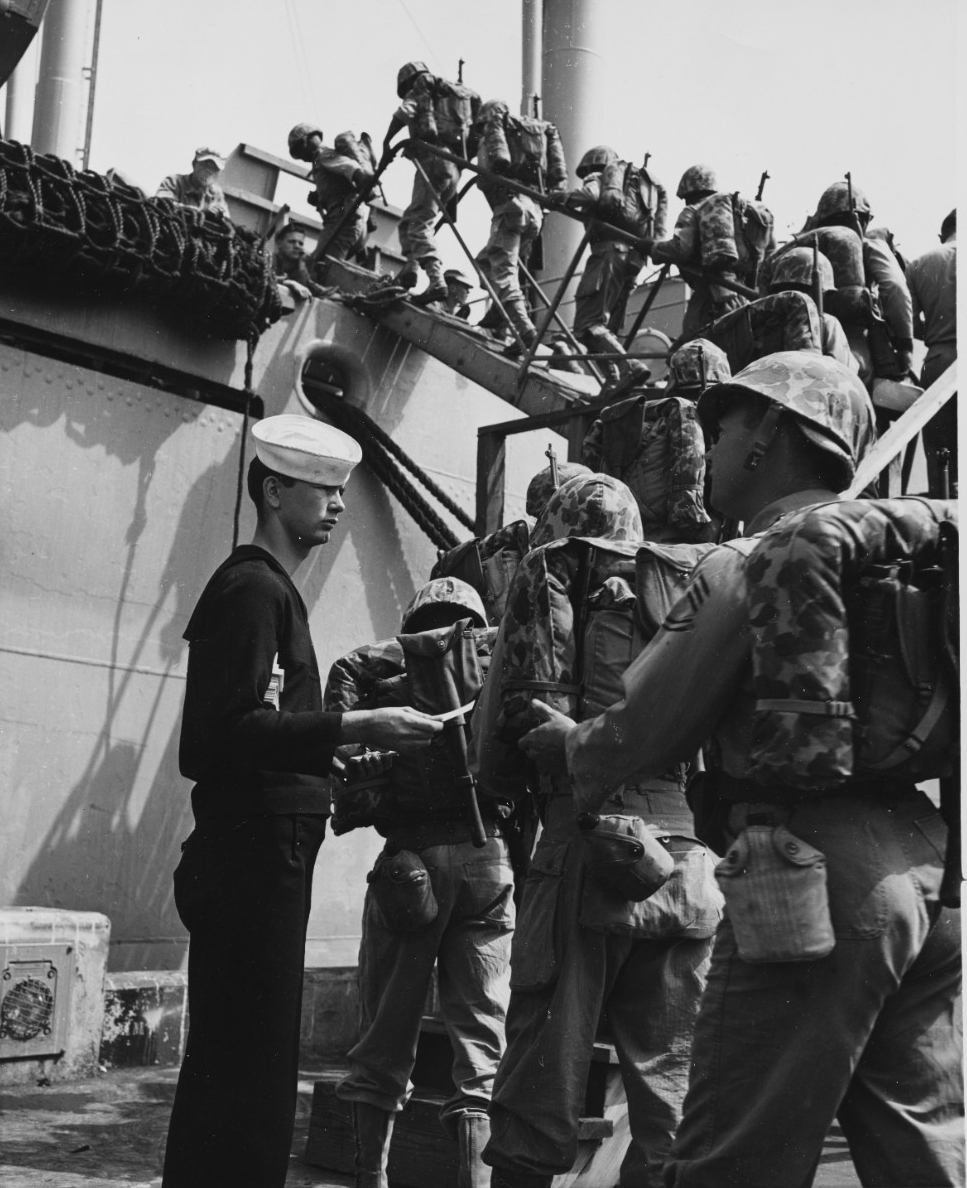

Also on 12 July, the first increment of the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade (Reinforced) sailed from San Diego en route Korea in Task Group 53.7 exactly ten days after receiving its first warning order. The brigade included the 5th Marine Regiment, plus artillery, support units, and two F4U Corsair fighter squadrons (48 aircraft), plus an F4U-5N night fighter squadron, all of Marine Air Group 33. The lift force included Gunston Hall (LSD-5) and Fort Marion (LSD-22), along with three attack transports, three attack cargo ships, and one transport. Escort carrier Badoeng Strait (CVE-116) transported the brigade’s aircraft. The marginal state of readiness of the U.S. Navy was apparent when the well deck of Fort Marion accidentally flooded, damaging a number of Marine tanks. Attack transport Henrico (APA-45), which had survived a bad kamikaze hit at Okinawa in 1945, had to turn back for mechanical repairs, which were completed with great haste. She then resumed her transit (and actually got to Japan first).

In the meantime, a major reinforcement of U.S. Navy logistics capability in the Korean area was underway. These ships included two destroyer tenders, three fleet oilers, two gasoline tankers, two repair ships, five fleet tugs, three cargo ships, one reefer, and an LSD converging from Guam, Pearl Harbor, and the U.S. West Coast. The lone hospital ship and only fleet stores ship in the Pacific had been decommissioned due to budget cuts. (Fortunately, the British had thought to keep a hospital ship in the Far East—the RFA Maine).

Carrier Boxer’s Record-Breaking Transit

On 14 July 1950, despite being only one of three operational Essex-class carriers in the Pacific, Boxer (CV-21), was pressed into service as an aircraft ferry. She departed Alameda, California, with a cargo of 145 Air Force F-51 (formerly P-51) Mustang fighters, six Stinson L-5 Sentinel observation aircraft, 19 U.S. Navy aircraft, 1,012 Air Force ground support personnel, a Marine air control element, and 2,000 tons of critical aviation supplies (stripped from Air National Guard units due to acute shortages). Boxer reached Yokosuka, Japan, in 8 days and 7 hours, the fastest trans-Pacific transit recorded. That is, until her return transit to Alameda in 7 days, 10 hours, and 36 minutes. She picked up her own air group (CVG-2, consisting of 110 F4U Corsair fighter-bombers and no jets) and then sailed for Korea, arriving in September. (Of note, Boxer was the first aircraft carrier to launch a jet aircraft, an FJ1 Fury, in March 1948.)

Battle of Taejon Debacle, 14–21 July 1950

Following the defeat of Task Force Smith near Osan, the Army’s 24th Infantry Division continued to try to slow the North Korean advance, suffering another defeat near Pyongteak, with engagements culminating in a major battle near Taejon as the NKPA advanced toward Pusan. Although air strikes continued to mow down large numbers of North Korean troops, tanks, and supply trucks, the 24th Infantry Division had no answer for the T-34 tanks or the North Korean’s highly effective fix-and-flank tactics (often resulting in a classic double envelopment—see Hannibal at the Battle of Cannae in 216 BC). The fighting was so fierce, desperate, and at such close quarters that the division commander, Major General William F. Dean, personally knocked out a North Korean tank with a hand grenade. In the end, the division was overwhelmed and forced back toward Pusan yet again, suffering over 3,600 soldiers killed and almost 3,000 captured (many of whom were executed). Dean became separated while trying to get through a North Korean roadblock, and ended up wandering alone in the hills for several weeks before finally being captured and becoming the senior U.S. POW during the war. He would be awarded a Medal of Honor.

Pohang Landing and Additional Actions, Mid-July 1950

On 14 July, 6,000 U.S. Marines of the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade’s main body sailed from San Diego en route to Korea.

On 15 July, Task Force 90 embarked two regimental combat teams (RCTs—10,000 troops) of the U.S. Army’s Japan-based 1st Cavalry Division for transport by sea to Pohangdong, South Korea, in a hastily planned and executed—but successful—amphibious movement of troops. This operation, code named “Bluehearts,” had originally been planned as an amphibious landing at Inchon or Kunson on the west coast of South Korea, but the situation in the southeast had become so dire that those ambitious plans were abandoned in favor of getting the division into the Pusan Perimeter while there was still time. An amphibious landing at Pohang was necessary because the port of Pusan was completely clogged with shipping supporting the U.S. 24th and 25th Infantry Divisions.

Commanded by Rear Admiral James H. Doyle, embarked on Mount McKinley, TF 90 included attack transport Cavalier, three attack cargo ships including USS Union (AKA-106), and Military Sea Transportation Service (MSTS) Oglethorpe and Titania. In addition, there were 16 LSTs (15 of them Japanese-manned), and additional transports (some of them also Japanese-manned), led by six minesweepers, and covered by Juneau, three U.S. destroyers, and an Australian frigate. Additional Japanese-manned LSTs and cargo ships made up a follow-on force.

On 16 July, the headquarters of Fleet Air Wing 1 shifted from Guam to Naha, Okinawa, to direct VP patrol squadron operations over the Formosa Strait.

On 18 and 19 July, Juneau and HMS Belfast laid down effective fire near Yangdok on the east coast of South Korea, slowing the North Korean advance down the coast road toward Pohang. The bombardments killed over 400 North Koreans, and preserved Pohang (for the time being) for the administrative off-load of the two 1st Cavalry Division’s regimental combat teams (RCT 5 and RCT 8) to bolster the collapsing defenses around Pusan. Heavy cruiser Rochester guarded the transports while TF 77 provided air cover for the off-load, but as there was no North Korean opposition, the carriers proceeded into the Sea of Japan. The administrative landing of the 1st Cavalry Division was complete by 30 July.

Carrier Strikes on North Korea Resume, 18 July 1950

On 18 July 1950, TF 77 carriers Valley Forge and HMS Triumph resumed attacks on North Korea, this time from the east, bombing airfields, railroads and factories at Hamhung, Hungnam, Numpyong, and Wonsan. The strike on the oil refinery at Wonsan was particularly effective. Ten Corsairs led the attack on the refinery, firing high-velocity aerial rockets (HVAR), followed by 11 Skyraiders dropping 1,000-pound and 500-pound bombs and firing HVARs. The refinery was totally destroyed and thousands of tons of refined oil burned for days in a column of smoke that could be seen for over 60 miles. (The U.S. Air Force subsequently hit the refinery with B-29 heavy bombers, leaving little left standing).

For the remainder of the month, the TF 77 carriers launched interdiction strikes deep behind enemy lines as well as increasing numbers of close air support missions for increasingly desperate U.S. and South Korean forces being forced back toward Pusan. All of TF 77 remained on the move, shifting from the Sea of Japan to the Yellow Sea and attacking from the west. Close air support procedures were a major weakness and fixing them would be one of the most important developments of this period.

Communications between Army units on the ground and Navy and Air Force aircraft were atrocious (although to be fair, communications were clobbered across the entire theater, as the amount of message traffic outstripped capacity—some things never change). Air Force aircraft (almost all flying from Japan at this point) were given communications priority because they had very limited on-station time due to the distance from Japan. The result was numerous wasted Navy sorties that circled in vain waiting to be called in on targets, much to the annoyance of Vice Admiral Struble, who preferred to use the mobile capability of TF 77 to strike more meaningful targets in the North Korean rear. Nevertheless, the NKPA was paying dearly for its continued advance as a result of Navy and Air Force air strikes, more so due to the interdiction strikes than the close air support. However, it was apparent that air strikes alone, even effective ones, could not stop an advancing army by themselves.

First U.S. Navy Combat Loss: Ensign Donald Stevens, 19 July 1950

On 19 July, Ensign Donald E. Stevens of VA-55 off Valley Forge was shot down and killed in an AD-4 Skyraider during a strafing run at Kangmyong-ni, thus becoming the first naval aviator lost in action in Korea. Although North Korean anti-aircraft weapons were generally ineffective, the large volume of small-arms fire that could be put up by the large numbers of North Korean troops was becoming increasingly dangerous.

Additional Naval Actions, Mid–Late July 1950

Back in the United States, on 20 July, the U.S. Navy activated 14 squadrons of Organized Reserve for deployment to Korea, including eight carrier fighter squadrons, two carrier attack squadrons, one ASW squadron, one fleet aircraft service squadron, and two patrol squadrons.

On 22 July, TF 77 aircraft from Valley Forge and Triumph attacked the airfield and other targets around Haeju, North Korea (on the southern side of North Korea’s west coast), as well as targets near North Korean-occupied Inchon on the coast of South Korea west of Seoul. TF 77 then commenced a return transit to Japan to refuel, rearm, and resupply. (The ability of the U.S. Navy to sustain itself at sea via underway replenishment, critical to victory against Japan in World War II, had been severely diminished as a result of the aforementioned severe postwar budget cuts.)

Also on 22 July, ROKN auxiliary minesweeper YMS-513 sank another three North Korean supply craft near Chulpo in southwestern South Korea. Less than a week later, on 27 July, the newly acquired ROKN submarine chasers PC-702 and -703 ventured even farther north along the western coast of North Korean–occupied South Korea and bombarded Inchon harbor. The vessels then caught numerous North Korean sampans loaded with ammunition west of Inchon and sank 12 of them. In the first week of August, ROKN YMS-302 and other ROKN units destroyed 13 Communist logistics craft off the west coast of South Korea. Between August 13 and 21, the ROKN engaged enemy seaborne supply attempts five times and, in one instance, YMS-503 sank 15 craft and captured 30 that were trying to supply NKPA forces attacking the Pusan Perimeter.

Arrival of Escort Carriers Badoeng Strait and Sicily

Of the approximately 120 escort carriers built in the United States during World War II (of which some went to the British), only about half a dozen were still in commission in 1950. At the start of the Korean War, Badoeng Strait (CVE-116), which was commissioned too late to see combat service in World War II, was on a midshipmen cruise from San Diego to Pearl Harbor. She disembarked the midshipmen in Pearl Harbor, returned to San Diego, embarked Marine Air Group 33 F4U Corsairs, and departed en route the Far East. She arrived in Yokosuka, Japan, on 22 July, for the first of three deployments to Korea. On 27 July, she collided with dock landing ship Gunston Hall, fortunately with only minor damage. Marine F4U Corsair squadron VMF-323 would operate from Badoeng Strait and VMF-214 from Sicily (CVE-118) in providing close air support to U.S. Marines once they went ashore at Pusan.

Although Sicily was launched in April 1945, construction slowed with the end of the war and she wasn’t commissioned until February 1946. Sicily had transferred from the Atlantic to her new homeport in San Diego in April 1950. On 2 July, she received orders to proceed to the Korean theater and she got underway two days later with a cargo of ammunition, arriving in Yokosuka on 26 July. She off-loaded her ASW air group at Guam prior to arriving in Japan, and would subsequently embark U.S. Marine Corsairs of VMF-214 (the “Black Sheep” squadron). The two Marine Corsair squadrons, VMF-214 and VMF-323, comprised Marine Air Group 33 (MAG 33), which also included an observation squadron (VMO-6), and an air control unit (Marine Tactical Air Control Squadron 1). The night fighters disembarked and stayed in Japan.

The Escort Carrier Task Group (TG 96.8) was commanded by Commander, Carrier Division 15, Rear Admiral Richard W. Ruble. Ruble had been awarded a Silver Star as navigator of the carrier Enterprise (CV-6) during the Doolittle Raid and the battles of Midway, Eastern Solomons, and Santa Cruz in World War II.

Onboard USS Valley Forge (CV-45), flight deck tractors tow Grumman F9F Panther fighters forward on the flight deck in preparation for catapulting them off to attack North Korean targets, July 1950. This photograph was released for publication on 21 July 1950. Valley Forge had launched air strikes on 3–4 July and 18–19 July (NH 96978).

Additional Actions, Mid- to Late July 1950

On 24 July, dissatisfied with the ad hoc escort arrangement made for the Pohang landing, COMNAVFE established a dedicated Escort Element (CTE 96.50), under Captain A.D.H. Jay, RN, initially comprised of British frigates HMS Black Swan, HMS Hart, and HMS Shoalhaven.

On 27 July, Vice Admiral Turner Joy directed CTF 90 to plan and execute harassing and demolition raids along the Korean coast utilizing Navy underwater demolition teams (UDT) and Marine reconnaissance forces.

On 1 August, the U.S. Army 2nd Infantry Division was landed by sea at Pusan, to bolster the 1st Cavalry Division and replacing the badly-mauled 24th Infantry Division. As Japanese garrison divisions, both the 1st Cavalry and 2nd Infantry Divisions were afflicted with many of the same maladies as the unfortunate 24th Division, but had the advantage of somewhat more time to prepare before being thrown into battle, as well as the advantage of continuing massive attrition inflicted on North Korean forces by U.S. Navy and Air Force air strikes.

Carrier Philippine Sea Arrives

On 1 August, the Essex-class fleet carrier Philippine Sea (CV-47) arrived at Buckner Bay, Okinawa, becoming the third carrier (and second U.S. carrier) to join TF 77. Rear Admiral Edward C. Ewen, who had been awarded a Navy Cross in command of the first “night carrier,” Independence (CVL-22), in 1944, broke his flag on Philippine Sea. The carrier had transferred from the Atlantic to her new homeport of San Diego in late May 1950. Originally scheduled to deploy to the Far East in October 1950, her departure was accelerated to 5 July and her two fighter squadrons, VF-111 and VF-112, completed their transition training from prop to F9F Panther jets in Hawaiian waters before the ship sailed from Pearl Harbor on 27 July.

Like Valley Forge, Philippine Sea had not been completed in time to see action in World War II, but her “low mileage” kept her from being put in the reserve. Also like Valley Forge, her air group (CVG-11), included two F9F Panther jet fighter squadrons (VF-111 and VF-112), two F4U Corsair Squadrons (VF-113 and VF-114), and an AD-4 Skyraider squadron (VA-115). On 4 August, she departed Okinawa for combat operations. Philippine Sea’s first combat flights would mark the beginning of three consecutive years of U.S. carrier operations off Korea, as at least one carrier remained on station while the other went to Japan for refueling and re-arming.

Also on 1 August 1950, COMNAVFE directed Badoeng Strait and Sicily to proceed to a location off Pusan to provide close air support to the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade (Reinforced), about to go ashore at Pusan .

That same day, light cruiser HMS Belfast and frigate HMAS Bataan bombarded shore batteries at Haeju Man on the west coast of South Korea. Two days later, Royal Navy destroyers Cockade and Cossack bombarded Mokpo Harbor on the west coast in response to intelligence that many North Korean supply craft were there. However, spotting by a U.S. Navy VP-6 Neptune determined most of the vessels were gone, so docks and railroad sidings were shelled instead with good result. Bombardment missions on the west coast were no easy feat due to the extreme tidal variance (amongst the highest in the world, sometimes as much as 30 feet), which necessitated long approaches in constrained time frames and in poorly charted waters.

The Marines Have Landed, 2 August 1950

On 2 August 1950, the first elements of the U.S. Marine Corps 1st Provisional Brigade were delivered by sea to Pusan to bolster the defense of the perimeter at the most critical time. In what was very much a “last stand” by UN forces before being run into the sea, the Marines played a vital role. Originally the brigade was to remain in Japan to prepare for the Operation Bluehearts amphibious assault behind North Korean lines, but the situation around Pusan had become so desperate that the Marines had to be committed immediately. Several times, they were used to blunt and then repel major NKPA penetrations of the Pusan Perimeter. For the next six weeks, UN forces managed to hold the line, in some cases just barely, against repeated North Korean assaults, at a very high cost of about 5,000 U.S. killed, as more and more U.N. (mostly U.S). reinforcements arrived. Due to high attrition of North Korean forces and the continued arrival of U.S. reinforcements, eventually the number of defenders significantly outnumbered the North Korean attackers, but still the NKPA kept attacking.

Early on 3 August, Sicily launched eight VMF-214 “Black Sheep” F4U-4B Corsairs for an attack with rockets and incendiary bombs against North Korean troops at Chinju, near the southern coast of South Korea west of Pusan. Thus, VMF-214 became the first Marine squadron to see combat in Korea. This was the beginning of a sustained and effective interdiction and close air support mission for the Marines ashore by Marine fighter-bombers flying from the U.S. Navy escort carriers. Although the Marines also suffered close air support teething problems, they overcame them more quickly than the other services.

During the few days when the Marines ashore were moving forward to contact outside Pusan, Sicily steamed into the Yellow Sea. The Marine Corsairs provided fighter cover as the light cruisers HMS Belfast and HMS Kenya steamed through constricted waters to shell oil storage facilities, factories, warehouses, and gun positions, aided by spotting from a VP-6 Neptune. Over the next days, VMF-214 also flew interdiction missions along roads to the north. In addition, a Marine Corsair put a napalm bomb into a building near Inchon being used by the North Koreans for tank maintenance, burning the tanks inside.

On the night of 4–5 August, a UDT from the fast transport Diachenko (APD-123) attempted to blow up railroad bridges north of Yosu, on the south coast of South Korea (which would be the Marine brigade’s initial sector), to disrupt North Korean supply efforts, as the North Koreans were becoming increasingly short of gasoline in particular. However, the UDT was counter-detected and driven off by a North Korean patrol. After retrieving the UDT, Diachenko countered by shelling the rail yard. On 12 August, destroyer Collett (DD-730) steamed into Yosu Gulf and bombarded the town’s transportation infrastructure. On 15 August, frigates HMS Mounts Bay and HMCS Cayuga pretty much leveled what was left of Yosu.

At 0645 on 6 August, Badoeng Strait (CVE-116) joined in the close air support mission, launching Corsairs from VMF-323 “Death Rattlers” against North Korean positions near Chinju. VMF-323 strikes throughout the day knocked out bridges, a railroad round house, and vehicles. Moreover, instead of defending passively, and with the aid of the air cover, the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade (Task Force Kean) actually went on the attack. On 7 August, it stopped the North Korean advance along the southern coast road just west of Chinhae cold, inflicting massive North Korean casualties as the Marines advanced. (However, on 14 August, the Marines would be called off the attack, giving up hard-won ground, in order to plug a breach in the Pusan Perimeter when the North Korean 4th Division broke through the U.S. Arm’sy 24th Infantry Division yet again).

On 11 August, VMF-323 Corsairs and USAF F-51 Mustangs caught about 100 vehicles of the North Korean 83rd Motorcycle Regiment in the open, inflicting massive casualties in what was known as the “Kosong Turkey Shoot.” On 10 August, Captain Vivian M. Moses was shot down, rescued by a Marine helicopter, and returned to Badoeng Strait the following day. Captain Moses was on the carrier for only one hour before getting in another plane, only to be shot down and killed while attacking the North Korean regiment, and becoming the first Marine aviator killed in the Korean War. Moses was awarded a Distinguished Flying Cross and Purple Heart posthumously.

Cruiser Bombardments, August 1950

On 4 August, heavy cruiser Toledo (CA-133) and destroyer Collet, engaged in a combined air-sea strike along with U.S. Air Force aircraft near Yandok, on the east coast of South Korea north of the port of Pohang, in a reasonably effective attempt to impede the NKPA 5th Infantry Division advance toward the port. Due to the effective naval gunfire and star-shell illumination from the cruiser, this was the only section of the battle line around Pusan that remained stable, for a time.

Toledo had returned to Long Beach on 12 June from a Far East deployment, only to be ordered ten days later to return to the Korean theater. After a quick stop in Pearl Harbor, she arrived at Sasebo, Japan, and embarked Rear Admiral J. M. Higgins, commander of Cruiser Division FIVE (CRUDIV 5). On 26 July, Toledo arrived off the coast of South Korea, combining with Destroyer Division NINE ONE (DESDIV 91) to form Task Group 95.5 as one of two alternating East Coast Support Elements (referred to as Bombardment Groups in some sources, because that is what they did). Helena (CA-75) and destroyers Collett and Mansfield had shelled North Korean targets along the east coast road from 27 to 30 July, the first time 8-inch guns had been used on North Korean targets, and then returned to shell some more on 3 August. On 5 August, responding to airborne controllers, Helena’s 8-inch guns provided call-for-fire support to beleaguered UN troops ashore. She then moved 70 miles north and destroyed a bridge and cratered roads along the east coast of South Korea.

On 7 August, Helena commenced fire on railroad marshalling yards, trains, and a power plant at Tanchon, North Korea, after assuming duty from Toledo as the flagship of TG 95.5. This was the northernmost bombardment since light cruiser Juneau’s operations in early July. Like Toledo, Helena had just concluded a Far East deployment in June 1950, only to be ordered on 5 July to return to the Far East. There, she joined Rochester and Toledo with their 8-inch guns (three triple turrets) as the largest surface combatants (and the biggest guns) in the theater until the arrival of the battleship Missouri (BB-63) in September 1950. (Missouri was the only one of the four Iowa-class battleships that hadn’t yet been put in mothballs along with all the other fast battleships from World War II). On 14 August, gunfire from Helena destroyed a North Korean train along the east coast railroad in South Korea.

On 15 August, Toledo returned from resupply in Japan and continued bombardment operations against North Korean troop concentrations north of Pohang, joined by Rochester, and destroyers Mansfield, Collett, and Lyman K. Swenson (DD-729). After a dash north, Toledo and her escorts shelled railroad bridges and several hundred freight cars along the northeast coast of North Korea on 17 August. Although NKPA troops eventually forced their way into Pohang, they were unable to hold it due to heavy losses inflicted by naval gunfire support and airstrikes by Navy and Air Force aircraft. Thus, the support of the cruisers and destroyers was vital in enabling the ROK troops defending the northern flank of the Pusan Perimeter to finally hold the line after weeks of defeat and retreat.

Other Actions in August 1950

On 4 August, Vice Admiral Struble, commander of Seventh Fleet, designated Juneau to be the flagship of the Formosa Patrol Force (TG 77.3), which initially consisted of Juneau and destroyers Maddox (DD 731) and Samuel N. Moore (DD-747), and oiler Cimarron (AO-22), with a tall order of deterring the PRC from invading Nationalist Formosa. Juneau was selected for this duty because among the U.S. cruisers her 5-inch main battery guns were the least effective in knocking out concrete bridges and emplacements (due to smaller caliber). The Formosa (Taiwan) Straits patrol rarely numbered more than two surface ships, but endured until the late 1970s.

Also on 4 August, Fleet Air Wing 6 was established in Tokyo under the acting command of Captain John C. Alderman, assuming operational control over all U.S. and British patrol squadrons.

On 11 August, British light carriers HMS Warrior (R-31), and HMS Ocean (R-68), arrived in theater, initially serving as troop transports and aircraft ferries, although in later deployments they would serve as operational aircraft carriers.

On the night of 15–16 August, the first in a series of night raids on Korean east coast took place by a landing party from a Navy underwater demolition team and Marine reconnaissance unit embarked in fast transport Horace A. Bass (APD-124), which was configured to carry about 160 troops. Three night raids took place, destroying two bridges and three tunnels. During daylight, Horace A. Bass shelled North Korean targets. Between 20 and 25 August, the raiding parties off Horace A. Bass conducted reconnaissance of potential beaches for a major amphibious assault behind North Korean lines.

USS Badoeng Strait (CVE-116) loading Marine Corps F4U-4B Corsair fighters at Naval Air Station North Island, San Diego, California, for transportation to Korea, July 1950. Badoeng Strait carried planes and aircrew of Marine Air Group 33 as part of the trans-Pacific movement of the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade, the initial Marine Corps deployment of the Korean War. She left San Diego in mid-July and arrived at Kobe, Japan on 31 July (NH 96995).

A new capability to conduct raids arrived in early August: the converted transport submarine Perch (ASSP-313, formerly SS-313). In early September, Perch would conduct the first submarine raid, transporting a group of Britain’s 41 (Independent) Commando Royal Marines to destroy a train tunnel near Tanchon, North Korea. Perch’s commanding officer, Lieutenant Commander R. D. Quinn, was awarded a Bronze Star for this action, becoming the only submarine commander to receive a combat award during the Korean War. Submarine Pickerel (SS-524) had previously obtained periscope photography of the target in support of this mission.

On 16 August, the East Coast Support Element ONE (TE 96.51) successfully evacuated the entire ROK 3rd Division from its position south of Yongdok, as the division had been out-flanked and cut off. Four LSTs, one manned by Koreans and three by Japanese, executed the evacuation, covered by destroyer Wiltsie (DD-716). Having bypassed the South Korean division, North Korean troops were advancing quickly toward the port of Pohang, which anchored the eastern end of the Pusan Perimeter. Accurate gunfire from heavy cruiser Helena knocked out several North Korean tanks and slowed—but could not stop—the advance, and a column of T-34 tanks broke into Pohang. The evacuated ROK 3rd Division would subsequently play a key role in ejecting the North Koreans from Pohang with the help of U.S. air support.

On 17 August, elements of the 1st Marine Division sailed from the U.S. West Coast, en route Korea.

On 18 August, ROK Marines, covered by ROKN guns, landed and captured the city of Tangyong (on a peninsula on the south coast of Korea west of Chinhae and Pusan), helping to hold the southern flank of the Pusan Perimeter.

Decision for the Inchon Landing, 20 August 1950