H-033-2: USS Parche and Commander “Red” Ramage’s Medal of Honor

By mid-1944, U.S. submarines were taking an appalling toll on Japanese merchant shipping as well as sinking Japanese warships with regularity. This included deliberately targeting escorting destroyers, of which the Japanese were becoming critically short. By this time, the U.S. submarine forces had found fixes and work-arounds to the deficiencies in U.S. torpedoes that had resulted in numerous missed opportunities to sink aircraft carriers and numerous ships in the first years of the war, and had even resulted in losses of U.S. submarines due to failure of torpedoes to work as designed. In addition, many of the overly cautious skippers in the initial years had been replaced by a new breed of younger, more aggressive commanding officers and, as a result, effectiveness went up, but also so did losses (52 U.S. submarines would be lost in World War II). Just as important, however, was the steady stream of intelligence derived from breaking Japanese navy and merchant codes, and by radio traffic analysis. By 1944, the provision of timely “sanitized” Ultra intelligence had significantly solved the “big ocean, little periscope” problem. U.S. submarines, often operating in wolf packs of three or more submarines, were regularly in the right place at the right time thanks to the intelligence they were receiving.

For Japan, the improvement in U.S. submarine effectiveness in 1944 was catastrophic, particularly for troopship convoys, which were high priority to attack. The loss of so many troopships had a severe effect on Japanese morale, despite extensive efforts to conceal the losses, and further poisoned the already severely dysfunctional relationship between the Japanese navy and Japanese army, which blamed the navy (rightly) with failing to protect the troopships from attack.

Among the most devastating losses in 1944 was the attack on 8 February by Snook (SS-279) that sank the troopship Lima Maru, with the loss of 2,765 troops and crew. Others followed. On 24 February, Rasher (SS-269) sank Ryusei Maru (4,998 killed). The same day, Rasher sank Tango Maru, which unfortunately was carrying 3,500 Javanese laborers and several hundred Allied prisoners of war, with 3,000 mostly Javanese lost. On 1 March, Trout (SS-202) sank Sakito Maru (2,475 lost). On 16 March, Tautog (SS-199) sank Nichiren Maru (1,934 lost). On 26 April, Jack (SS-259) sank Yoshida Maru No. 1 (2,649 lost). On 29 June, Sturgeon (SS-187) sank Toyama Maru (5,400 killed, the greatest loss of life in a ship sunk by a U.S. submarine). On 30 June, Tang (SS-306) sank the troopship Nikkin Maru (3,219 killed). On 19 August, Spadefish (SS-411) sank Tamatsu Maru (as many as 4,755 killed). The same day, Rasher sank Teia Maru (2,655 killed). On 18 November, Picuda (SS-382) sank Mayasan Maru (3,546 killed). Troopship losses dropped off toward the end of 1944 as the Japanese simply gave up trying to move troops by sea, meaning that islands under attack had no hope of reinforcement.

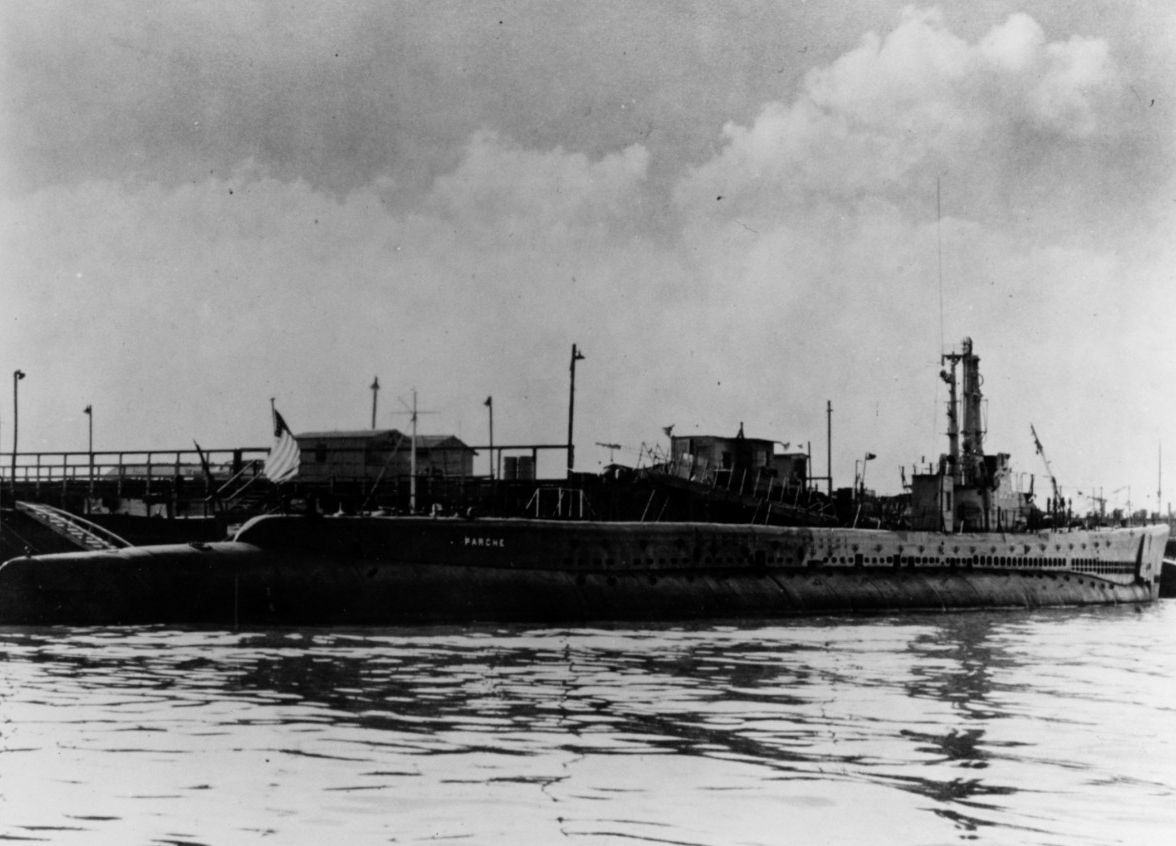

The Balao-class fleet submarine USS Parche (SS-384) was commissioned on 20 November 1943 with Commander Lawson P. “Red” Ramage as her first skipper. The Balao class was the most numerous U.S. submarine in World War II (120 commissioned, 62 cancelled) first entering service in mid-1943. (The 77 submarines of the preceding Gato class first entered service right as the war broke out). The Balao class was very similar to the Gato, with the biggest difference being higher-yield strength steel that increased test depth to 400 feet from 300 feet. Both classes were armed with ten torpedo tubes (six forward and four aft) and normally carried 24 torpedoes, usually the Mark 14, which were notoriously unreliable in the first years of the war (see H-Gram 008/H-008-3 for more on U.S. submarine torpedoes in World War II). The Balao-class boats were armed (some were re-armed) with a larger 5-inch/25-caliber deck gun and usually had one single Bofors 40-mm mount and a twin Oerlikon 20-mm mount for anti-aircraft protection (which was Parche’s configuration). The Gato-class submarines were initially armed with a 3-inch deck gun, and early Balao-class boats had a 4-inch deck gun. However, due to constant modifications and upgrades to radars, sensors, and guns, pretty much no two Balao’s looked alike. The normal complement was 10 officers and 70–71 enlisted men.

Lawson P. Ramage (known as “Red” due to his red hair) graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1931 (almost all U.S. submarine commanders in World War II were USNA graduates). Unable to pass the submarine physical due to an eye injury incurred while wrestling at Annapolis, Ramage resorted to memorizing the eye chart, finally entering the submarine service and reporting to S-29 (SS-134) in 1936. He was at Pearl Harbor on the staff of Commander, Submarines Pacific during the attack on 7 December 1941. On his first war patrol as navigator of Grenadier (SS-210), Ramage was awarded a Silver Star.

Ramage assumed command of Trout (SS-202) in June 1942, conducting four war patrols. On his first war patrol on Trout, Ramage became the first U.S. submarine commander to score a hit on a Japanese carrier, the escort carrier Taiyo near Truk on 22 September 1942, which survived being hit by one torpedo of five fired. On his next patrol, on 12 November, Ramage would fire five torpedoes at the battleship Kirishima, which was on her way to bombard U.S. Marines on Guadalcanal. However, all five torpedoes either failed to hit or to detonate. Had they worked, the outcome of the bloody night battles off Guadalcanal on 12–13 and 14–15 November might have been very different, or might not have happened. Although Ramage sank three other ships and was awarded a Navy Cross, his patrols on Trout were plagued by dud torpedoes and he became one of the most vocal critics of the defective Mark 14.

In May 1943, Commander Ramage assumed command of the new construction Parche (SS-384). Parche’s first war patrol was in March–May 1944 south of Formosa as part of a three-submarine wolf pack, which included Bang (SS-385) and Tinosa (SS-283), and sank seven ships, with Parche credited with two of them (Taiyoku Maru and Shoryu Maru).

Parche’s second war patrol commenced 17 June 1944 and was also part of a wolf pack that included Hammerhead (SS-364) and Steelhead (SS-280) again operating south of Formosa. Parche sank a patrol boat and celebrated 4 July by being fired upon and depth-charged by a Japanese cruiser and destroyer. On 29 July, Hammerhead sighted a Japanese convoy and pursued, but failed, to score any hits, and her contact report was garbled, causing confusion and delay on Parche and Steelhead, which spent the next day searching while being repeatedly forced under by aircraft.

On the night of 30–31 July, Parche commenced a coordinated attack with Steelhead, commanded by Commander Dave Whelchel, with Steelhead attacking first. In a 46-minute pre-dawn melee that followed, Ramage became a legend, taking Parche right into the middle of the convoy for a night surface attack during which Parche fired 19 torpedoes. At one point, Japanese defensive fire became so intense that Ramage ordered all his topside crew to go below, except for one stern lookout (most accounts say Ramage remained on the bridge alone, but his own account said he kept the lookout with him). At one point, Ramage narrowly avoided being rammed by a Japanese ship that was making a deliberate attempt to do so, missing by only 50 feet.

Coordinating with Steelhead, Ramage sank the Manko Maru, the 10,000-ton tanker Koei Maru, and the 8,990-ton troopship Yoshino Maru, which went down with massive loss of life. Of 5,063 soldiers on board, 2,442 were lost, along with 35 crewmen, 18 gunners, and a large quantity of ammunition. Meanwhile, Steelhead sank another transport and a cargo vessel. Between the two submarines, another tanker and a cargo ship were damaged. Both submarines escaped without damage. Whelchel would be awarded a Silver Star. Ramage would be awarded the Medal of Honor and the Parche was awarded a Presidential Unit Citation for two war patrols that included the attack.

Ramage’s Medal of Honor citation follows:

“For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty as commanding officer of the USS PARCHE in a pre-dawn attack on a Japanese convoy, 31 July 1944. Boldly penetrating the screen of a heavily escorted convoy, CDR Ramage launched a perilous surface attack by delivering a crippling stern shot into a freighter and quickly followed up with a series of bow and stern torpedoes to sink the leading tanker and damage a second one. Exposed by the light of bursting flares and bravely defiant of terrific shellfire passing close overhead, he struck again, sinking a transport by two forward reloads. In the mounting fury of fire from the damaged and sinking tanker, he calmly ordered his men below, remaining on the bridge to fight it out with an enemy now disorganized and confused. Swift to act as a transport closed to ram, CDR Ramage daringly swung the stern of the speeding PARCHE as she crossed the bow of the onrushing ship, clearing by less than 50 feet but placing his submarined in a deadly crossfire from escorts on all sides and with the transport dead ahead. Undaunted, he sent three smashing “down the throat” bow shots to stop the target, then scored a killing hit as a climax to 46 minutes of violent action with the PARCHE and her valiant fighting company retiring victorious and unscathed.”

Parche would go on to complete six war patrols and earn five battle stars, and Ramage would be awarded another Navy Cross and a Bronze Star. Ramage would rank 50th among U.S. submarine commanders in terms of tonnage sunk, credited with sinking 10 ships of 77,200 tons, which was revised by post-war analysis to 7.5 ships of 36,700 tons. Parche would be used as a target for the atomic bomb tests at Bikini Atoll in July 1946, surviving both blasts relatively undamaged. She was decontaminated and served as a reserve training boat until being scrapped in 1970. Her superstructure is preserved as a memorial at the Pearl Harbor submarine base.

Ramage continued to serve after the war, and was promoted to rear admiral in 1956. As deputy commander of Submarine Forces Atlantic Fleet, he led the search for the lost nuclear submarine USS Thresher (SSN-593) in 1963. Promoted to vice admiral, he served as the Deputy Chief of Naval Operations for Operations and Readiness, commander of the First Fleet, and commander of the Military Sea Transportation Service before retiring in 1969. The Arleigh Burke–class destroyer USS Ramage (DDG-61), commissioned in 1995, is named in his honor.

Sources include: NHHC Dictionary of American Fighting Ships (DANFS) for U.S. vessels; combinedfleet.com for Japanese vessels; and “Lawson P. ‘Red’ Ramage” by Dr. Edward Whitman at ussnautilus.org, website of the NHHC Submarine Force Museum and Library Foundation.