H-Gram 021: Operation Avalanche, Fritz X, and the Battle of Durazzo

18 September 2018

Contents

1. 75th Anniversary of World War II: Operation Avalanche—The Invasion of Italy, September 1943

Download a pdf of H-Gram 021 (4.75 MB).

("Back issue" H-grams can be found here.)

75th Anniversary of World War II

Operation Avalanche—The Invasion of Italy, September 1943

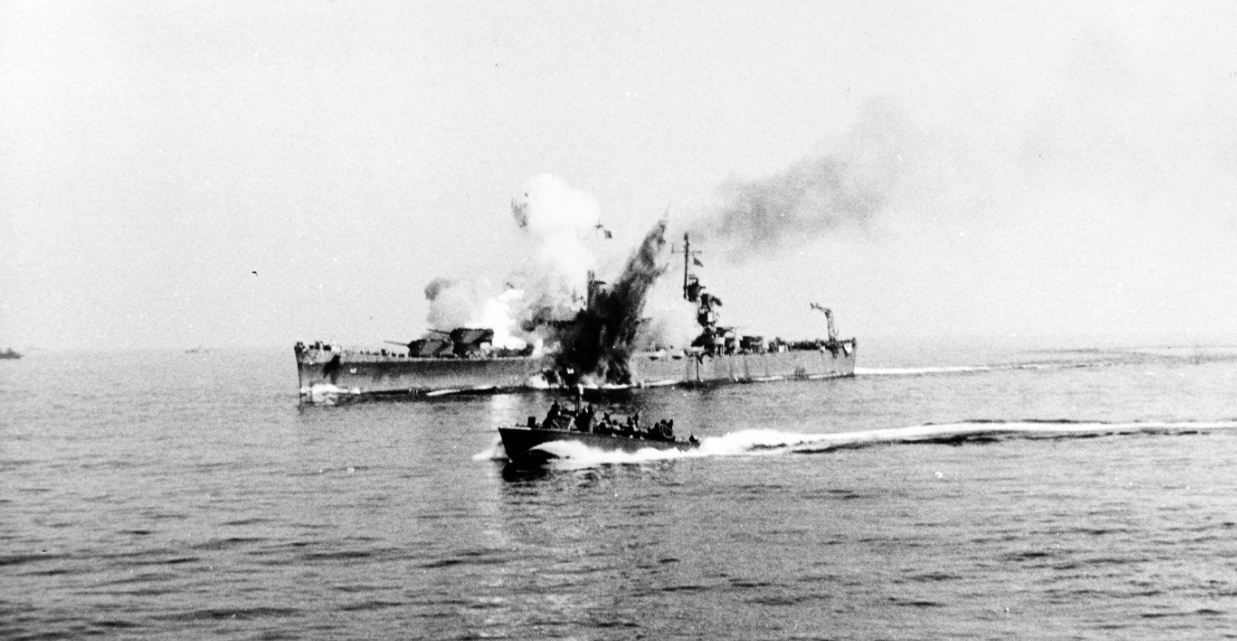

On 11 September 1943, the day after the light cruiser USS Savannah (CL-42) inflicted serious damage on German armor attempting to throw the Allied invasion force back into the sea at Salerno, Italy, the Luftwaffe struck back with a new weapon that would change the nature of warfare forever: the Fritz X, a radio-controlled glide-bomb that was the world's first precision-guided weapon deployed in combat— and the first to sink a ship. Dropped from over 18,000 feet, well above shipboard anti-aircraft fire, the 3,000-pound Fritz X achieved trans-sonic velocity as the operator aboard the Dornier Do 217K-2 twin-engine bomber guided the weapon to a direct hit on Savannah's No. 3 turret, penetrating the armored roof all the way to the lower ammunition handling room, where it exploded, blowing out the bottom of the ship (which prevented a magazine explosion due to the massive influx of water) and opening a long seam in the side of her hull. For 30 minutes, secondary explosions wracked the forward part of the ship and the forecastle came within inches of going under.

The explosions and toxic gases killed 197 Savannah crewmen, about one fifth of the crew, and all but a handful of men forward of the superstructure, including the entire No. 1 damage control crew in central station. The explosions snuffed out all boilers, leaving the ship listing and dead in the water for eight hours. Nevertheless, led by Captain Robert W. Carey (who already had a Medal of Honor and a Navy Cross to his credit), her surviving crew rallied, and, in an extraordinary feat of damage control, stopped the flooding, corrected the list, put out the fires, re-lit the boilers, resumed firing on German positions from the cruiser’s aft turrets, and made it to Malta under her own power, an incredible example of toughness and resilience by a crew that was not about to give up their ship. Two days earlier, German aircraft had sunk Roma, the largest battleship in the Italian navy, as she was steaming to switch sides from the Axis to the Allies. Two Fritz X hits sent Roma to the bottom with a catastrophic explosion and the loss of 1,393 Italian sailors, including the commander of the Italian fleet, Vice Admiral Carlo Bergamini.

Operation Avalanche, the Allied amphibious landings at Salerno, Italy, beginning on 9 September 1943, were nearly a disaster. Lulled by word of an armistice between Italy and the Allies, and hopeful of meeting minimal or no resistance from Italian forces, the American and British troops who landed at Salerno instead found themselves outnumbered by German Panzer divisions ready and willing to fight. German counterattacks were so aggressive that at one point the U.S. commander, General Mark Clark, wanted his troops evacuated off the beach and consolidated with the British. Admiral Kent Hewitt, the U.S. naval commander (and overall Allied amphibious force commander) helped convince Clark otherwise. Although great credit most go to the stiff resistance of American and British ground forces in the face of determined German attempts to push them back off the beachhead, much must also go to the naval gunfire support provided by U.S. and British ships, especially the rapid-fire six-inch guns of Savannah and her sister, USS Philadelphia (CL-41), and later USS Boise (CL-47), of the class known by the Japanese as "machine-gun cruisers" (armament that was a double-edged sword when the ships ran out of flashless powder in night battles in the Solomons). The German ground forces and artillery had no answer for the firepower from the light cruisers, which decimated multiple German tank attacks and caused the ships to be put at the very top of the Luftwaffe's target list in their attempt to defeat the landing.

After a vicious and bloody fight ashore, and multiple Allied ships being hit and put out of action by German guided glide bombs (for which the Allies had no initial answer), including the British battleship HMS Warspite, the Allies nevertheless carried the day, and established a major foothold in Italy. This would be followed by a protracted, costly, high-casualty campaign, which neither the Americans nor the Germans wanted. The U.S. Navy would lose three destroyers and over 800 men in the Salerno operation, making it one of the costliest naval operations of the war.

Please see this H-gram’s attachments for more on the Fritz X (H-021-1) and Operation Avalanche and the precursor invasion of Sicily, Operation Husky (H-021-2)

100th Anniversary of World War I

As World War I reached its bloody culmination in August–September 1918, during which the overwhelming number of U.S. Army Expeditionary Force troops began to roll back the Germans, there were several significant U.S. Navy developments:

- On 21 August 1918, Navy Enlisted Pilot Charles Hammann landed his own damaged seaplane in the northern Adriatic to rescue a fellow downed naval aviator who had been shot down by Austro-Hungarian aircraft defending the naval base at Pola. In doing so, Hammann would become the first U.S. aviator of any service to be awarded the Medal of Honor.

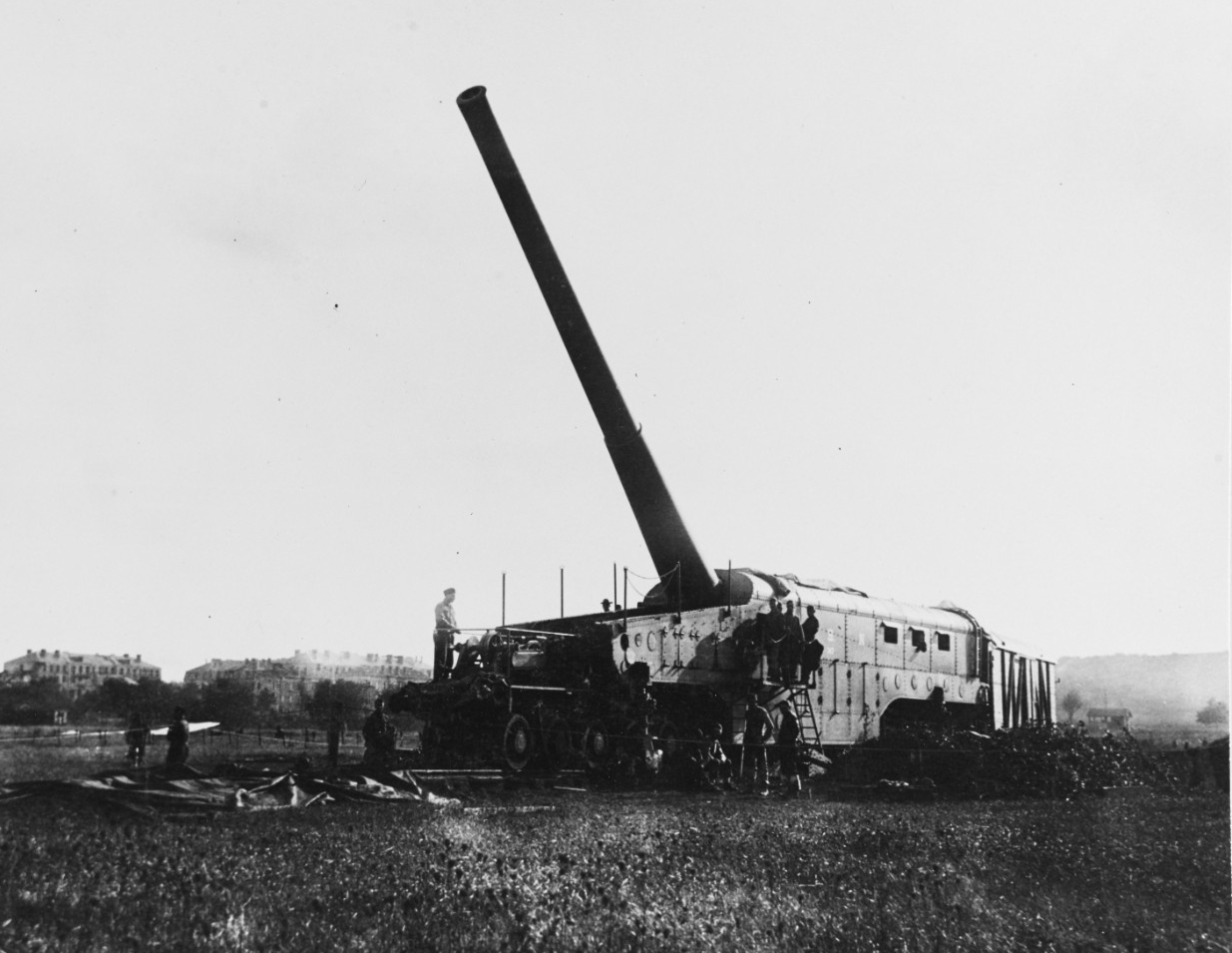

- On 6 September, a U.S. Navy 14-inch railway gun on the Western Front in France opened fire on German strategic positions. Five U.S. railway guns would fire over 700 rounds at German targets in the last two months of the war (including possibly the very last shot of the war). The U.S. Navy railway guns represented an extraordinary example of innovation, rapid prototyping, production, testing, acquisition, and deployment.

- On 20 September 1918, Lieutenant David Ingalls, USNR, became the first U.S. Navy "ace" (and the only U.S. Navy ace during the conflict), when he shot down his fifth German aircraft, a lone fighter. Flying with a Royal Air Force Sopwith Camel squadron, Ingalls would finish with six kills, including a German observation balloon.

- On 26 September 1918, the U.S. Coast Guard cutter Tampa, under U.S. Navy wartime subordination, was torpedoed and sunk by German submarine UB-91 in the Bristol Channel off Wales, with the loss of all 131 people aboard (111 U.S. Coast Guard, four U.S. Navy, 11 Royal Navy enlisted sailors, and 5 British dockyard workers). This was largest loss of U.S. life aboard a warship due to enemy action in World War I. As a result, the U.S. Coast Guard suffered proportionately the largest loss of life of any U.S. service during the war.

- On 2 October 1918, twelve U.S. Navy submarine chasers participated in a surface action and bombardment off Durazzo, Albania, the only surface action of the war in which U.S. vessels were engaged. During the battle, the U.S. sub chasers were part of a combined Italian, British, and Australian force. The U.S. vessels engaged two Austro-Hungarian destroyers, a torpedo boat, and damaged two submarines. Despite heavy enemy fire, damage to U.S. vessels was minimal, although the press played it up as a "suicide mission" against overwhelming opposition. Nevertheless, the U.S. submarine chasers acquitted themselves well in the first U.S. Navy surface battle since the Spanish-American War.

For more on the above events, please see attachment H-021-3.