H-010-6: Attacks on the U.S. Mainland in World War I and World War II

H-Gram 010, Attachment 6

Samuel J. Cox, Director NHHC

September 2017

Japanese Actions in World War II

Shortly after Pearl Harbor, seven Japanese submarines commenced operations off the West Coast of the United States, with intent to shell targets in California on Christmas Eve 1941. The operation was initially postponed to 27 December, and then cancelled by the Japanese for fear of U.S. retaliation on the Japanese homeland. Over the next year, Japanese subs contented themselves with sinking ten U.S., Canadian, and Mexican merchant ships, some within sight of the U.S. mainland. The Japanese I-25 also sank the Soviet submarine L-16 with all 50 hands (a big “oops” since the Soviet Union was at that time neutral in the war between Japan and the rest of the Allies). At the time, the L-16 was transferring from the Soviet Pacific Fleet to the Soviet Northern Fleet via the Panama Canal. A U.S. Navy chief photographer’s mate serving as an liaison officer was also lost aboard the Soviet sub.

On 23 February 1942, the Japanese submarine I-17 shelled the Ellwood Oil Field west of Santa Barbara, California, inflicting minor damage (but triggering an invasion scare on the U.S. West Coast, which served as additional pretext for interning Japanese-American U.S. citizens). It was followed on the night of 24–25 February by the “Battle of Los Angeles,” ihich jittery American anti-aircraft gunners unleashed an intense barrage over the city at non-existent Japanese aircraft, an action “extremely” loosely depicted in the Steven Spielberg/John Belushi movie 1941. In the movie, the submarine that provoked the movie hysteria was the “I-19” which in reality was the floatplane-equipped Japanese submarine that sank the USS Wasp (CV-7) on 15 September 1942.

Before conducting her floatplane attack on Oregon, the I-25 also shelled Fort Stevens, at the mouth of the Columbia River, on the night of 21–22 June, the only attack on a mainland U.S. military post during the war, which damaged some phone cables and a baseball backstop. U.S. shore gunners requested permission to open fire on the submarine, but were denied out of concern that doing so would give away number, position and capability of U.S. defenses prior to an actual invasion, thus depriving U.S. coastal artillery of their only opportunity to shoot at a real Japanese ship during the war. (Another Japanese submarine shelled a target in Canada, but all rounds missed.)

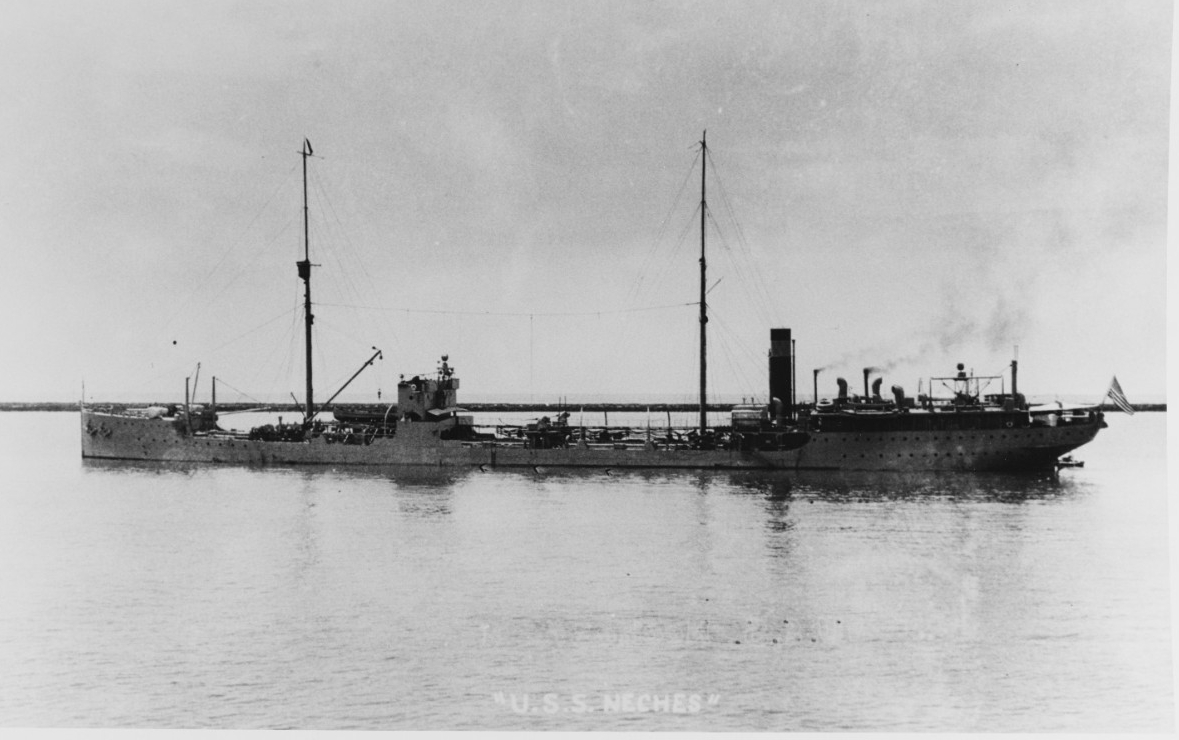

The Japanese submarine force was fixated on the idea that its purpose was to attack and whittle down the U.S. battle fleet in preparation for the decisive battle between the U.S. and Japanese battleships expected to occur in the western Pacific. The force never adapted to the idea of sinking merchant ships or auxiliaries (although the U.S. had an ample supply of fuel oil at Pearl Harbor—thanks to the Japanese failure to bomb the oil tanks during the raid on Pearl Harbor, oilers capable of refueling at sea were in very short supply). The sinking of the USS Neches (AO-5) by Japanese submarine I-72 off Pearl Harbor on 22 January 1942 and the loss of USS Neosho (AO-23) by air attack at the Battle of the Coral Sea that May 1942 significantly impacted U.S. fleet operations. Japanese submarines would regularly bombard U.S. Marine positions on Guadalcanal and occasionally on other islands, but few would ever be considered effective attacks. I-25 would be sunk by USS Ellet (DD-398) off the New Hebrides Islands on 3 September 1943.

Although the Japanese navy conducted no further shore bombardments of the U.S. mainland, between November 1944 and early 1945, in retaliation for the commencement of U.S. B-29 raids from the Marianas Islands in November 1944, the Japanese released over 9,000 balloons carrying incendiary devices (“fire bombs”) toward the United States, some launched from submarines, but most from the Japanese mainland itself, riding the Pacific jet stream. Approximately 300 are believed to have reached North America, causing a number of fires. Tight wartime censorship prevented the Japanese (or the American public) from getting any “BDA” on their balloon attacks. Six Americans were killed (a woman and five children) when one of the children found an unexploded device and disturbed it, setting off an explosion. These were the only confirmed deaths due to enemy action on the U.S. mainland during World War II. (The U.S. fire-bombing raid on Tokyo on the night of 9–10 March 1945 killed between 80,000 and 100,000 Japanese civilians.)

German Actions in World War II

Although German U-boats sank numerous Allied merchant ships just off the U.S. East Coast and Gulf of Mexico, they never opted to shell the U.S. mainland. The U-507 did sink the tanker Virginia right in the mouth of the Mississippi River on 12 May 1942. Another German submarine did shell the American Standard Oil refinery on the Dutch Caribbean island of Aruba in early 1942. However, on 12 June 1942, the German submarine U-202 landed a party of four agents at Amagansett, New York (Long Island), whose mission was to destroy power plants at Niagara Falls and several aluminum factories across the U.S. After landing, the team leader quickly turned himself in to the FBI and compromised the rest of the team, who were promptly arrested. On 17 June 1942, U-584 landed a second team of four agents at Ponte Verde Beach (near Jacksonville), Florida, tasked to attack multiple targets in the U.S., including New York City’s water-supply pipes. They were also compromised by the first team leader’s defection. Although the teams had landed wearing military uniforms, they were captured in civilian clothes. All eight were tried by military tribunal; six were executed as spies, and two who had turned themselves in were given 30-year sentences before being deported to Germany in 1948.

On 29 November 1944, the Germans tried again with much the same result. U-1230 landed two agents at Hancock Point, Maine, with intent to gather intelligence. One soon turned himself into the FBI, resulting in the other’s capture. Both were sentenced to death, but the sentences were commuted.

German Actions in World War I

The most damaging attacks on the U.S. mainland by a foreign power (not counting the War of 1812 and the American Revolution) were actually carried out during World War I by a German sabotage ring. On 30 July 1916, the major munitions storage depot and loading facility at Black Tom Island in Jersey City, New Jersey, exploded with a massive blast felt for a hundred miles, blowing out most of the windows in lower Manhattan, damaging the Statue of Liberty (the stair to the torch has been closed ever since), killing at least four people, and injuring hundreds as 2,000,000 pounds of small arms and artillery ammunition and 100,000 pounds of TNT detonated, all destined for Russia. At that time, the United States was officially neutral, but U.S. businesses were happily selling arms and ammunition to anyone who would buy them, although the British Royal Navy’s blockade of Germany meant that in reality almost all the U.S.-manufactured arms and ammunition were going to the Allies. The German government repeatedly objected to this one-way trade, to no avail.

The initial investigation pinned the blame for the Black Tom Blast on a Slovak immigrant (who later served in the U.S. Army after the U.S. entered the war), who had delivered a suitcase that triggered the blast; however, he was mostly an unwitting agent of a German sabotage ring. Subsequent investigation by the Office Naval Intelligence (which had counter-espionage as a primary mission at the time) revealed one of the most incredibly complex spy and sabotage rings in history. The details go beyond the scope of this paper, but are worthy of a Le Carré novel, and included Germans, Communists, Mexicans, the Irish anti-British Clan na Gael group, the Indian anti-British Ghadar Party (mostly Sikhs,) and other gun-running mercenaries, mostly operating out of San Francisco. (The break-up of an arms-smuggling effort by elements of this group resulted in the most sensational and highly publicized trial of the day, sometimes referred to as the “Hindu-German Plot.”) A key member of the ring was a German naval officer, Lieutenant Lothar Witzke. At the start of World War I, Witzke was an officer aboard the German light cruiser SMS Dresden, which after running amok for several months in the Pacific, was eventually trapped in some islands off Chile (the British flagrantly violated Chilean neutrality in the process). The Dresden subsequently scuttled herself and her crew was interned in Chile for the duration of the war. Witzke, however, escaped from Chile on a merchant ship, which he jumped in San Francisco, where he eventually met up with the master German spy Kurt Jahnke. The two were primarily responsible for several espionage and sabotage events, including the Black Tom blast.

After the U.S. entered the war, Jahnke relocated to Mexico, but with Witzke conducted another spectacular sabotage attack in the United States, when, on the morning of 9 July 1917, a massive blast rocked the Mare Island Shipyard and numerous barges filled with munitions, killing six, wounding 31, and causing damage across a wide area of northern San Francisco Bay. Witzke would eventually be caught and imprisoned before being pardoned by President Calvin Coolidge (and sent back to Germany, where he served the Third Reich with as much zeal as Imperial Germany). Jahnke also served Nazi Germany, and he and his wife were both captured and executed by the Soviets in April 1945. Although the munitions that Jahnke and Witzke had blown up at Black Tom had been destined for Czarist Russia (which subsequently sued the U.S. government for lax security that enabled the blast), the Soviets weren’t any more forgiving than the Czar.