"Battles That You've Never Heard Of," Part 2

9 July 2021

Download a pdf of H-Gram 063 (4.9 MB).

Overview

This H-gram covers the Battle of the Pearl River Forts, China (1856); the Battle of Somatti, Fiji (1859; the Battle of Shimonoseki Strait, Japan (1863); the Formosa Expedition (1867); and the Battle of Ganghwa, Korea (1871). This H-gram includes cannibals!

Battle of the Pearl River Forts, China, 1856

In late 1856, as a detachment of U.S. Marines and sailors was withdrawing from the American compound in Canton, China, under a guarantee from the Chinese that U.S. interests would be protected during the outbreak of the second Opium War, a Chinese fort fired on a boat that was carrying Commander Andrew Hull Foote down the Pearl River to his ship, the sloop-of-war USS Portsmouth. The next day, the fort fired on a U.S. survey boat, killing the coxswain. Viewing the Chinese action as an egregious breach of good faith and an affront to the U.S. flag, the commander of the U.S. East Indies Squadron, Commodore James Armstrong, authorized Foote to take punitive action against the four Chinese forts that guarded the Pearl River approach to Canton. Armstrong was ill, and his flagship, the steam screw frigate San Jacinto, drew too much water to go up the river.

On 16 November 1856, two small steamships towed Portsmouth and sloop-of-war Levant upstream toward the forts. Levant ran aground, but Portsmouth engaged in an hours-long gunnery duel with the forts. Although she was damaged, Portsmouth’s fire was much more accurate. On 20 November, with Levant refloated, the two sail sloops (augmented by much of San Jacinto’s crew) were again towed within range of the Chinese forts. Once fire from the forts was suppressed, a 287-man detachment of Marines and armed sailors went ashore and captured the first fort from the landward side, turning its guns on the other three forts. The Marines beat off a 1,000-man Chinese counterattack with the considerable help of sailors with a wheeled boat howitzer. Over the next two days, the Marine and Navy force sequentially captured all four forts, and then set about demolishing them with explosives. During the course of the engagement, Portsmouth was hit 27 and Levant 22 times, but neither suffered critical damage, mostly attributable to bad Chinese gunnery. U.S. casualties included 7 killed in action, 3 killed in a demolition accident, and 32 wounded. Chinese casualties were estimated at 250–500 dead. For more on the Battle of the Pearl River Forts please see attachment H-063-1.

The Battle of Somatti, Fiji, 1859

The Fiji Islands were always regarded as a dangerous place to outsiders, and there had been previous skirmishes between the U.S. Navy and Fijian warriors (see H-Gram 062). In the summer of 1859, Fijian tribesmen on the island of Waya killed and cannibalized two American merchant seamen. The American consul in Fiji requested that the just-arrived sloop-of-war USS Vandalia take punitive action. As the water around Waya was too shallow for Vandalia, her skipper, Commander Arthur Sinclair, chartered the schooner Mechanic. Under the command of Lieutenant Charles Caldwell, Mechanic headed toward Waya with a party of 10 Marines, 40 sailors (with a 12-pounder lightweight wheeled boat howitzer), and three Fijian guides. After a harrowing nighttime climb up the steep mountainside, during which the howitzer got loose and fell down a 2,300-foot cliff, the landing party reached the summit at daybreak to find the Fijian warriors in full “battle dress” ready and waiting outside the village of Somatti. Despite their fearsome reputation, the warriors were no match for Marine rifles, nor did they appear ready to comprehend and counter a “flanking maneuver.” At least 14 Somatti warriors were killed, including two chiefs, before they retreated into the jungle. Six Americans were wounded. The gun crew then proceeded to burn down the 115-hut village. A number of other Fijian tribes were appreciative of the U.S. action in that they had also been victimized by the Somatti. In the end, Fiji became a British colony, and a British problem. For more on the Battle of Somatti, please see attachment H-063-2.

The Battle of Shimonoseki Strait, Japan, 1863

The “opening of Japan” by Commodore Mathew Perry in 1854, with steam warships and shell guns, did not meet with universal acclaim among the daimyo (feudal lords) of Japan. For the first time in centuries, the emperor became actively involved in the affairs of state as the Tokugawa Shogunate lost face and power as a result of acceding to Perry’s demands. In the spring of 1863, with the U.S. pre-occupied by the Civil War, Emperor Komei issued an “expel the barbarians” order. On the night of 25–26 June 1863, in defiance of the Shogunate, but in accord with the Emperor’s edict, ships of the Choshu daimyo fired on the American merchant ship Pembroke at the entrance to the Shimonoseki Strait (which connects the Inland Sea with the East China Sea). Choshu guns from six forts overlooking the strait subsequently fired on and hit French and Dutch ships in the next days. (Five of the guns were new 8-inch Dahlgren guns, courtesy of the United States.) Although the emperor’s order applied to all Western nations, the United States was the first to react.

On 16 July 1863, the steam screw sloop USS Wyoming (the only U.S. ship in the Far East at the time), under the command of Commander David McDougal, entered the Shimonoseki Strait ready for battle, expecting to be fired on. The Choshu did not disappoint. As soon as Wyoming was in range, all six forts opened up with a tremendous cannonade. However, McDougal had noted the range stakes in the strait, deducing that the Japanese had calibrated their guns to hit ships in the channel. Instead, McDougal steered so close to the shore that Japanese cannon balls missed 10–15 feet above the deck, tearing up the rigging and perforating the smokestack, but doing no serious damage. McDougal then headed toward the three armed Choshu ships at the far end of the channel, a sail bark, sail brig, and a steamer (all previously purchased from the United States). Wyoming passed the bark starboard-to-starboard at pistol-shot range as both ships emptied broadsides into the other. The heavier U.S. weapons were far more effective, although the Japanese got off three broadsides. Wyoming then did the same to the brig, leaving her in sinking condition.

Wyoming then passed the steamer port to port and engaged her with portside guns. She turned to port behind the steamer in order to open the range and use her two 11-inch Dahlgren pivot guns. In doing so, Wyoming ran aground. The steamer slipped her anchor and made a run at the screw sloop, either to ram or board, but Wyoming backed off in time. A well-aimed 11-inch shell passed clean through the steamer, but blew her boiler, causing her to sink in less than two minutes. Wyoming then re-engaged the brig with 11-inch guns and accelerated her trip to the bottom. The screw sloop put more rounds into the bark, leaving her severely damaged, and then worked over the forts until they were silent. Wyoming actually conserved ammunition because her primary mission was to engage the Confederate raider CSS Alabama, which was not in the Far East yet. Wyoming was hit in the hull 11 times and suffered five dead and six wounded. Japanese casualties are unknown, but were probably considerable as the ships were described as “heavily manned.”

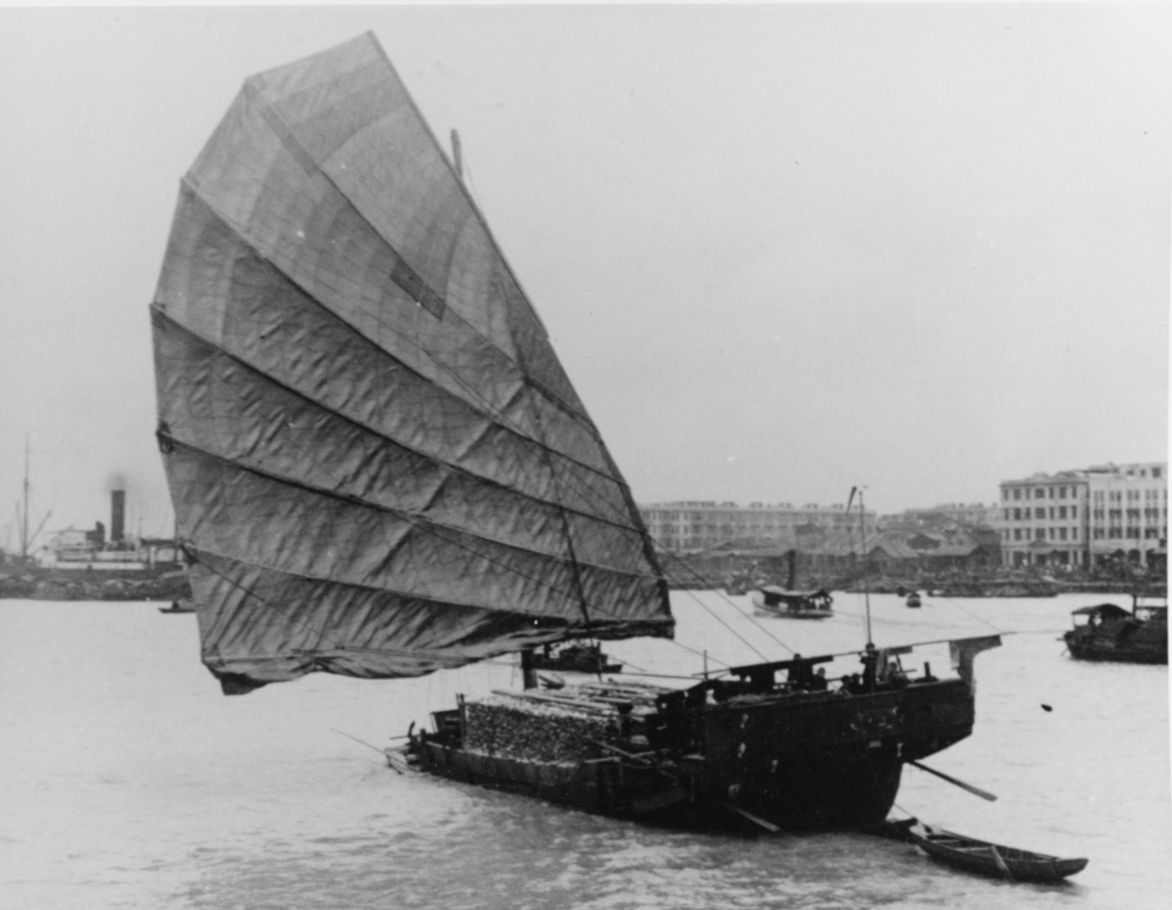

McDougal believed that the Choshu had gotten the intended message. However, they raised the sunken ships, re-armed the forts, and continued to block the strait for another 15 months. Finally, in early September 1864, a combined 18-ship British, French, Dutch, and U.S. force attacked the Choshu again. The U.S. contribution was token. By that time, the only U.S. ship in the region was the sail sloop USS Jamestown, and all the other ships of the other navies were steam-powered, making her more of a liability. As a result, Jamestown’s skipper, Captain Cicero Price, chartered the steam ship Ta-Kiang, put a 30-pounder Parrott gun on board along with 18 American crewmen, including a lieutenant and the surgeon, and then placed the ship under the command of the British admiral (which may have been a first). In the Second Battle of Shimonoseki Strait, Ta-Kiang performed useful service towing boats with British troops ashore and serving as a hospital ship for the “allied” force.

The end-result of these actions was a civil war in Japan (the “Boshin War” in 1868–69), in which forces siding with the emperor (Komei’s son, Meiji) gained the upper hand. However, the Tokugawa navy, led by Vice Admiral Enomoto Takeaki, refused to surrender and attempted to establish an independent republic on Hokkaido. The imperial forces cobbled together a fleet of ships from several daimyo (including the Choshu). The Tokugawa had purchased an ironclad ram from the United States in 1867. She was originally built in France for the Confederate Navy and commissioned as CSS Stonewall, although she didn’t reach the United States until after the Civil War ended. The United States held up delivery during the Boshin War, until it was obvious the Meiji forces were going to win (and Meiji wasn’t nearly as anti-foreign as his father). In the hands of the imperial navy, Stonewall (re-named Kotetsu—literally “Ironclad”) played a decisive role in the naval battle of Hakodate in 1869, in which the renegade Tokugawa navy was defeated (the action is considered the birth of the Imperial Japanese Navy).

President Theodore Roosevelt wrote, “Had that action [Shimonoseki Strait] taken place at any other time than the Civil War, its fame would have echoed all over the world.” For more on the Battle of Shimonoseki Strait, please see attachment H-063-3.

The Formosa Expedition, 1867

In March of 1867, aboriginal Paiwan warriors massacred the crew (including the captain’s wife) of the American merchant bark Rover, which had wrecked on the southern tip of Formosa. In June, the United States launched a punitive expedition. (Regular steamship service from the United States to the Far East had recently been instituted, enabling Washington to become involved and accelerate or delay overseas operations—compare with Wyoming’s deployment at Shimonoseki Strait.)

On 13 June, the U.S. East Indies flagship, screw sloop USS Hartford (of Civil War, Admiral Farragut, and “damn the torpedoes” fame) and USS Wyoming arrived off the area where Rover had wrecked. A force of 181 Marines and sailors, under the overall command of Commander George E. Belknap, went ashore. In a poorly conceived operation, with no intelligence as to the objective and terrain, nor even much of a plan upon reaching the objective other than to “punish the Paiwan,” the American forces thrashed around for hours in the steaming-hot jungle in two columns. The Paiwan were not taken by surprise and their defense consisted of a version of “rope-a-dope.” The mostly unseen Paiwan would loose spears, stones, and occasional musket fire, causing the Marines and sailors to charge until they were exhausted. With much of the force delirious and suffering from sunstroke and heat exhaustion, including the prostrate Commander Belknap, a Paiwan musket ball found its mark and mortally wounded Lieutenant Commander Alexander Slidell MacKenzie, leader of one of the columns. At this point, Belknap had had enough and the U.S. force withdrew. Paiwan casualties, if any, were unknown. Although an apparent failure, the expedition actually did impress the Paiwan, who subsequently signed an agreement with the U.S. consul not to kill any more shipwrecked sailors, to which they mostly adhered. For more on the Formosa Expedition, please see attachment H-063-4.

The Battle of Ganghwa, Korea, 1871

In August 1866, the American-flagged armed merchant schooner General Sherman sailed up the Taedong River to Pyongyang despite repeated Korean warnings to leave. Depending on the account, the purpose of General Sherman’s voyage was to open trade with isolationist Korea, loot Korean royal tombs, or spread the Gospel. Along the way, the schooner left Bibles on the riverbank, took a senior Korean official hostage and demanded ransom, fired on a crowd ashore (killing five), and ran aground. After several days of skirmishing, the governor of Pyongyang had had enough and ordered the ship destroyed by fire raft. The entire crew of General Sherman burned or drowned, except two who made it to shore and were beaten to death by an angry mob.

In May 1871, the U.S. Asiatic Squadron showed up to do something about it. Under the command of Rear Admiral John Rodgers (son of War of 1812 hero John Rodgers), the force included the flagship, screw frigate USS Colorado; two new screw sloops of war, USS Alaska and USS Benicia; and two sidewheel gunboats, USS Monocacy and the smaller USS Palos. Embarked on Colorado was the U.S. minister to China, Frederick Low, as the primary stated mission of the force was to open trade with Korea and also investigate what had really happened to General Sherman. Attempts at diplomacy were stymied, as the Koreans steadfastly refused to negotiate and demanded that the U.S. force leave.

On 1 June, four U.S. steam launches, supported by the two gunboats, commenced a survey of the Salee River, which separates the island of Ganghwa from the Korean mainland and leads to the Han River, which in turn leads to the Korean capital of Seoul. Without warning, Korean forts on both sides of the river opened fire, which fortunately was inaccurate. The steam launches immediately returned fire with their boat howitzers, quickly joined by the heavier guns of the gunboats. The U.S. vessels eventually withdrew in the treacherous currents after Monocacy was damaged when she hit an uncharted rock.

Although the U.S. vessels were clearly in what today would be considered internal territorial waters, violating Korean sovereignty, in the 1800s the U.S. and European powers assumed the right to steam anywhere in non-Western nations they pleased. Rodgers and Minister Low were outraged that the Koreans had had the temerity to fire on U.S. ships. The Koreans were given 10 days to apologize and commence serious trade negotiations. After 10 days with no satisfactory response from the Koreans, Rodgers commenced a punitive phase of the operation.

On 10 June, the steam launches and gunboats returned to the Salee River (the bigger ships couldn’t enter due to draft), this time towing 22 boats with a landing party of 109 Marines, 542 sailors, and 7 wheeled boat howitzers. The gunboats engaged the southernmost forts on the left (west) bank, fortunately causing most of the defenders to retreat. This was a lucky break, as the landing “beach” turned out to be a wide stretch of knee-deep muck. The Marines were able to capture the first fort in short order, but dragging the guns through the mud turned into an all-day affair under a blazing sun.

On 11 June, the Navy-Marine advance continued up the west bank of the river through very difficult terrain, capturing a second fort with the aid of naval gunfire (although Palos hit a rock and was forced out of the battle), and fighting through ambushes and small-scale counterattacks by Koreans with antiquated weapons that were no match for U.S. Remington rifles and howitzers. By noon, the U.S. force was within 150 yards of the most formidable of the forts on the west bank, defended by about 300 Koreans (considered an elite force) commanded by General Eo Jae-yeon. Realizing the Koreans only had single-shot weapons, mostly old matchlocks, about 350 Marines and sailors rushed the fort and scaled the ramparts. The Koreans resorted to throwing stones and spears, and the battle quickly turned into a 15-minute close-quarters melee, in which superior U.S. weapons overcame considerable Korean bravery. General Eo was killed by a Marine sharpshooter and the Koreans finally broke and fled toward the river, where many were trapped by Americans still outside the fort and were cut down by howitzers. Many drowned in the river and many committed suicide rather than surrender.

As the American assault on the fort culminated, a force of about 4,000–5,000 Koreans was forming up for a counterattack from the landward side. At the same time, the one fort on the opposite side of the river opened fire, but was suppressed by fire from Monocacy. The howitzers ashore kept the large Korean force at bay thanks to a timely resupply of ammunition from Monocacy. When the Koreans realized the fort had fallen, they opted not to press the counterattack.

American casualties in the operation were three dead and ten wounded (and others temporarily felled by sunstroke). The two gunboats were damaged by rocks in the river and were in need of repair. Fifteen Medals of Honor were subsequently awarded (nine to sailors and five to Marines), almost all for the hand-to-hand battle inside the last fort. This was the first time the award had been presented for operations against an overseas foreign adversary. Korean casualties included 243 corpses counted of an estimated total of 350 dead. The forts on the west bank were all demolished and over 40 guns captured or destroyed.

Minister Low seemed chagrined that the carnage in the forts did not make the Koreans any more inclined to negotiate a trade treaty. The force ashore was withdrawn to the ships on 12 June. After waiting in placve for another two weeks with no formal response from the Koreans (local officials refused to even forward letters to the regent of Korea, the Daewongun, for fear of his wrath). On 3 July, Rodgers’s force steamed away with no trade treaty and little to show except for a daring, well-executed operation and a lot of dead Koreans, who were merely defending their country. The devastation of the Ganghwa forts did give impetus to factions in the Korean government who favored opening trade, at least enough to acquire decent weaponry. However, it was the Japanese who gained the advantage following a short battle at Ganghwa Island in 1875, which resulted in a Japanese-Korean trade treaty in 1876. The United States finally got a trade treaty with Korea in 1882. For more on the Battle of Ganghwa, please see attachment H-063-5.

As always, you are welcome to disseminate H-grams widely. One reason these battles are largely forgotten is that they are examples of what became derisively known as “gunboat diplomacy.” Although at the time the United States was not considered an imperial power (as we had no aspirations for colonies or more territory—although Mexico might dispute that), we exhibited the same attitude of superiority toward Asians, Africans, and South Americans that the European powers did. Although national policy and the decisions of senior U.S. Navy commanders are open to debate, what is not debatable is that the ordinary U.S. sailors did their duty as their country asked, with extraordinary courage, innovation, and skill, in a harsh and unforgiving environment.

“Back issues” of H-grams, enhanced with photographs, may be found here.