H-Gram 031: Operation Neptune, 6 June 1944—Special "D-Day" Edition

6 June 2019

Contents

- 75th Anniversary of World War II: Operation Neptune—the Amphibious Assault on Normandy, 6 June 1944

- 50th Anniversary of the Vietnam War: Collision of USS Frank E. Evans (DD-754) with HMAS Melbourne, 3 June 1969

75th Anniversary of World War II

Operation Neptune—the Amphibious Assault on Normandy, 6 June 1944

By H-hour on Omaha Beach (0630, 6 June 1944), pretty much everything had already gone to hell. Of 64 amphibious tanks that were supposed to land on the beach five minutes before the first infantry assault wave, 27 were on the bottom of the ocean, having sunk due to heavy seas. Four additional amphibious tanks had been destroyed when LCT-607 struck a mine and sank. That 28 of the tanks made it ashore was due to Lieutenant Dean Rockwell, USN, commander of LCT Flotilla 12, who assessed the seas as too rough and on his own initiative chose to take the tanks all the way to the beach at great risk to the eight LCTs that received his order. LCT-607 was lost on the way in. Another three tanks reached the beach because Ensign Henry Sullivan, in command of LCT-600, stopped launching tanks after the first one sank and took the rest of them all the way to the beach, also on his own initiative. Of the 28 tanks launched into the water from the other seven LCTs (which didn’t get Rockwell’s order), only two made the swim of 2–3 miles to the beach; the rest tragically sank with most of their crews.

The loss of the tanks, mostly due to sea conditions and not the enemy, wasn’t all that went wrong. The shore bombardment was only 30 minutes long, inadequate to take out most of the heavily fortified and well-concealed German gun positions. The Navy was aware of this based on experience with Japanese-held islands, but the need to minimize the amount of time for the German forces in reserve to react to the landing was considered by the Army to be of overriding importance. The strike by 450 B-24 heavy bombers just before the landing missed the beach due to overcast, and 13,000 bombs went long and did nothing except add to the din. Then, eight LCT(R) “rocket ships” fired 1,080 rockets each, and almost all of them fell short of the beach. Instead of the expected understrength German garrison division, the beach was defended by the first-line 352nd Infantry Division, which had just arrived to defend a beach that was ideally suited to defense.

The first U.S. troops to land at Omaha Beach were slaughtered by the hundreds. Some landing craft never made it to the beach; in others that did, no one got off alive. Navy coxswains whose craft were disabled wound up fighting as infantrymen using weapons taken from the dead. Navy combat demolition units were in the second wave in order to blow beach obstacles; most didn’t make it ashore. The same was true for the Navy beach battalions, beachmasters, and naval shore fire control teams. Navy physicians and corpsmen who went ashore in the first waves suffered high casualties, but were noted afterward to be “the bravest of the brave.” By 0830, Omaha Beach was so littered with destroyed and damaged landing craft, tanks, vehicles, un-cleared German obstacles (most mined), and hundreds of dead on the beach and drowned in the rising tide that the senior surviving Navy beachmaster called a halt to any further landings other than assault troops.

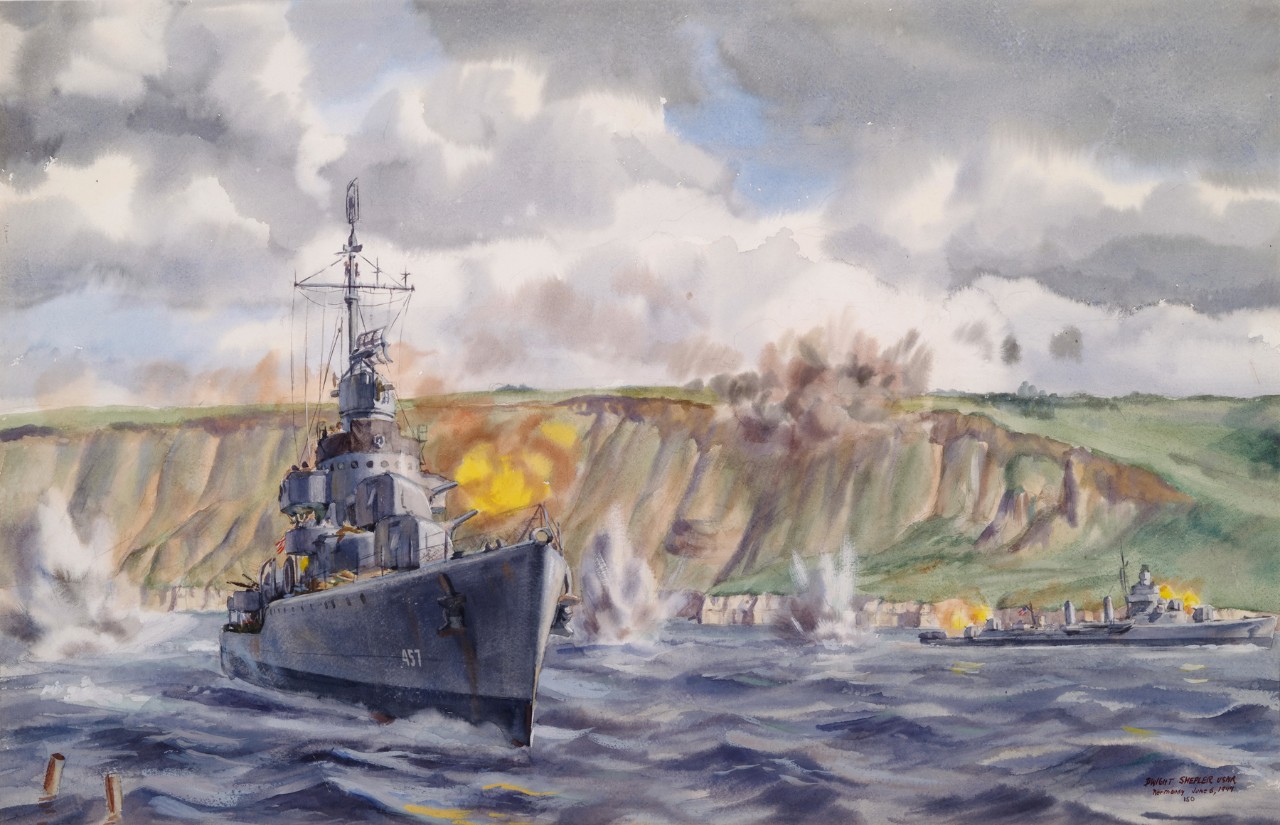

Although the Germans fought ferociously at the other four Normandy beaches, those landings went relatively well. However, at Omaha, the Germans were winning when several U.S. destroyers, acting on their own initiative, closed to within 800–1,000 yards of the beach (one to 400 yards, close enough to be hit by rifle fire). They found ways to innovate on the spot to provide fire support to troops without benefit of shore spotting (most of the troops’ radios had been lost in the surf). By 0950, all the U.S. destroyers plus three British destroyers were ordered to close the beach, risking mines, shore battery fire, and the likelihood of running aground in the shallows. As the fire from the destroyers finally began to take a serious toll on the German defenders, in one of the most extraordinary acts of mass courage in the history of the United States Army, with many of their leaders dead, the surviving soldiers fought their way up the 100-foot bluffs backing the beach. It was this epic bravery by the U.S. Army soldiers that carried the day at bloody Omaha Beach and their extraordinary valor should never be forgotten. However, in the words of the chief of staff of the 1st Infantry Division, Colonel Stanhope Mason, “without that gunfire [from the destroyers], we positively could not have crossed the beaches.” In the words of the V Corps commander, Major General Leonard Gerow, after he finally got ashore, “Thank God for the U.S. Navy.”

There are no comprehensive figures for U.S. Navy casualties on D-day that I can find, although one footnote in a medical report gives a number of 363 dead and 2,020 wounded. During the dedication of the Navy Memorial at Normandy in 2008, the figure of 1,068 Navy dead was cited, but not from an authoritative source, and that number would certainly include losses in the weeks before and after D-Day. In almost every account of D-Day, Navy losses are just rolled into overall Allied losses, generally considered to be about 10,000 casualties, of which 2,500 died (although recent research suggests a significantly higher toll of about 4,500 dead, mostly on Omaha Beach). Navy personnel climbed Pointe du Hoc with the Army Rangers, parachuted in with the airborne troops, manned the landing craft (along with many U.S. Coast Guard coxswains), and served in numerous roles in the first waves of the landing, suffering high casualties. Determining exactly how many of those men died is a challenge.

The U.S. Navy did, of course, keep an accurate count of how many warships were lost, and, in that regard, the week after D-Day was much more costly to the Navy than D-Day itself. The largest U.S. Navy ship lost on D-Day was the destroyer USS Corry (DD-463), hit by German shore fire and then probably succumbing to a mine in the opening moments of the bombardment of Utah Beach, in addition to the minesweeper Osprey (AM-56) and numerous amphibious craft, including 9 LCIs and 26 LCTs. But in the days that followed, the destroyers Glennon (DD-620) and Meredith (DD-726), destroyer escort Rich (DE-695), the minesweeper Tide (AM-125), five LSTs, and the troop transport Susan B. Anthony (AP-72) were sunk by the Germans, mostly by mines, as they protected the vital flow of more troops and supplies into the Normandy beachhead.

Although the great majority of ships involved in the invasion were British Royal Navy, and the ground troops of the United States, United Kingdom, and Canada deserve the credit for defeating the Germans ashore, the U.S. Navy played an absolutely critical part in what Supreme Allied Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower, termed “the great crusade” to defeat Germany and rid the world of Nazi tyranny.

For more on Operation Neptune, please see attachment H-031-1.

50th Anniversary of Vietnam War

Collision of USS Frank E. Evans (DD-754) with HMAS Melbourne, 3 June 1969

In June 1969, the destroyer Frank E. Evans (DD-754) was ordered to leave the Vietnam combat area to participate in a Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) exercise (Sea Spirit) in the South China Sea, after which she was to return to the Vietnam combat area. At about 0300 on 3 June 1969, due to error by the bridge watch, Frank E. Evans cut just in front of the Australian aircraft carrier HMAS Melbourne. At the last moment, both ships tried to avoid the collision, but it was too late and Melbourne sliced the destroyer in two. Her bow sank almost immediately while the stern half remained afloat (and was towed to Subic Bay). Seventy-four of Frank E. Evans’ crew were killed.

The subsequent joint Royal Australian Navy-–U.S. Navy board of inquiry proved to be very controversial, souring relations for a time between the services. The captain of Frank E. Evans (who was asleep at the time) and two lieutenants on watch were deemed guilty of negligence (the lieutenants pled guilty and the commanding officer was found guilty at court-martial). The commanding officer of Melbourne was taken to court-martial and acquitted. A training film was developed from the event, I Relieve You, Sir, which I still remember vividly from my midshipman days. The names of the 74 men lost on Frank E. Evans are not on the Vietnam War Memorial in Washington, DC, even though she was only a few miles outside the declared combat area. This was the worst loss of life aboard a Navy destroyer since the USS Hobson (DMS-26) was sunk in a nighttime collision with the carrier USS Wasp (CV-18) in 1952 with the loss of 176 crew, the greatest loss of U.S. Navy loss of life in an accident since World War II. I will write more about Frank E. Evans in the next H-gram, otherwise I will not get the attached D-Day article done before D-Day.