H-Gram 061: The Last Aerial Torpedo Attack

21 May 2021

Contents

Overview

This H-gram covers naval operations in the Korean War from March to July 1951, including carrier task force operations in the Formosa Strait (including the USS John A. Bole—DD-755—incident), “Carlson’s Canyon” air strikes, the torpedo strike on Hwachon Dam, and the floating mine strike on destroyer USS Walke (DD-723). Also covered is Part 3 of Operation Desert Storm, including the critical contribution of Navy sealift, Navy construction battalions, and Navy medicine to the successful conclusion of the operation.

70th Anniversary of the Korean War: U.S. Naval Operations, March–July 1951

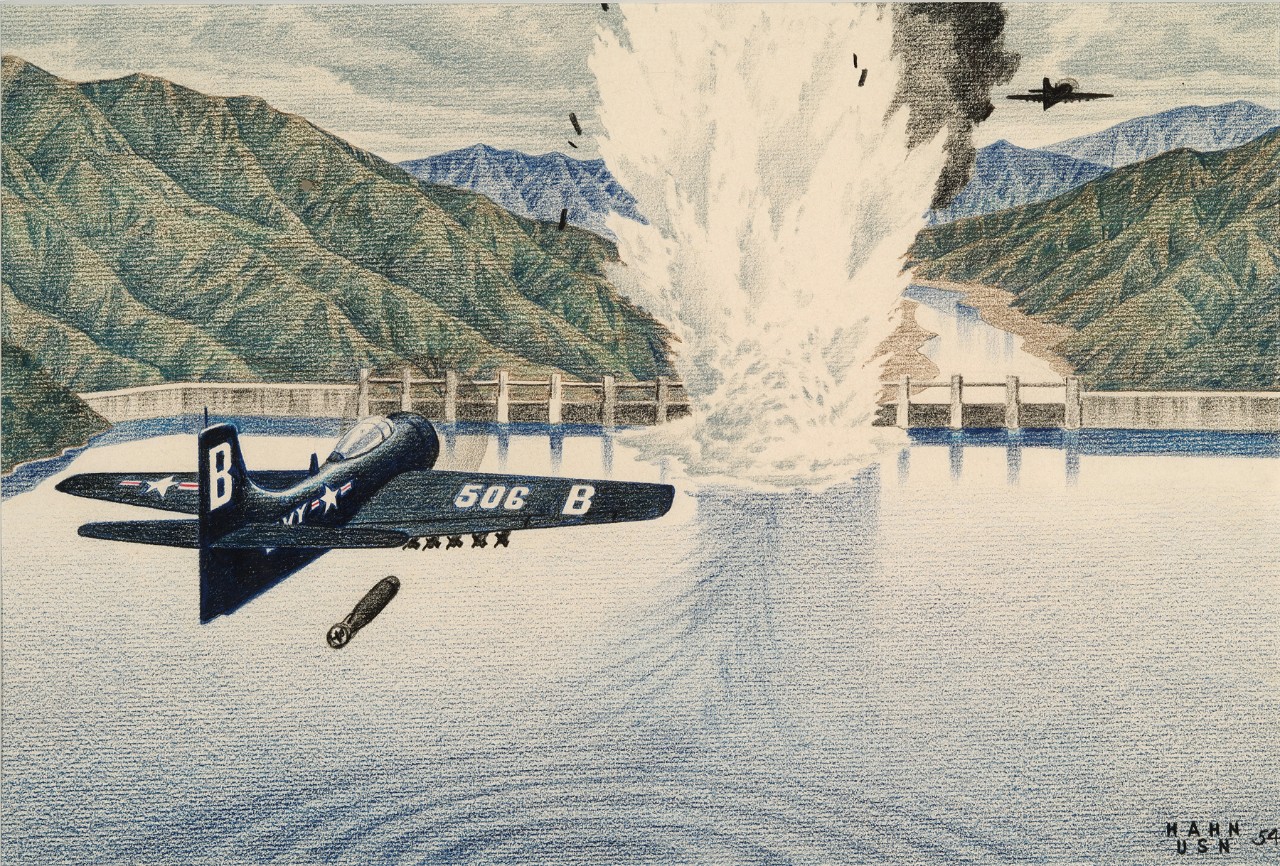

On 1 May 1951, eight Douglas AD Skyraiders off carrier Princeton (CV-37) threaded their way two-by-two through 4,000-foot mountain passes as F4U Corsairs flew ahead to provide flak suppression. As the Skyraiders reached the Hwachon Reservoir, they leveled off on a low-altitude torpedo attack profile, targeting the sluice gates on the massive Hwachon Dam. Although almost none of the pilots had any experience with torpedoes (none had been used since the end of World War II) all eight Skyraiders got their torpedoes away. One torpedo ran erratically, one was a dud, but six ran true, demolishing one sluice gate with two direct hits and putting another out of operation with one direct hit. Hitting the sluice gates deprived the Chinese troops and North Korean technicians on the dam from controlling the level of the Pukhan River, which separated U.S. and Chinese forces (lowering the river so Chinese troops could ford it without bridges, or inundating the valley if U.S. troops tried to cross). Previous attempts to knock out the dam using B-29 Superfortresses with 12,000-pound guided bombs or capturing it with Army Rangers had failed, as had an attempt the day prior by the same Skyraiders using 2,000-pound bombs and 11.5-inch “Tiny Tim” rockets with 500-pound warheads. Finally, Navy ingenuity prevailed to accomplish the mission. All eight torpedo plane pilots were awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for what was the last aerial torpedo attack in history against a surface target. The VA-195 “Tigers” subsequently changed their name to “Dambusters.”

Other significant events in the period included continuous (foul weather permitting) interdiction air strikes by Task Force 77 carrier aircraft against Chinese and North Korean logistics infrastructure such as bridges and tunnels, in a constant battle between strike aircraft and repair crews, who fixed bridges almost as fast as they could be knocked out of action. One of the more famous bridges came to be known as “Carlson’s Canyon,” for how many times Commander “Swede” Carlson’s VA-195 Skyraiders attacked it. In the end, the bridge was destroyed and the North Koreans built a bypass.

In mid-April 1951, the TF-77 carriers Boxer (CV-21) and Philippine Sea (CV-47) and escorts suddenly left the Sea of Japan and transited to the Formosa Strait as a show of force to deter a possible Communist Chinese invasion of Formosa, the last stronghold of the Nationalist Chinese. Carrier aircraft flew “aerial parades” along the 3–nautical mile limit of the Communist Chinese coast, drawing sporadic but ineffective ground fire. During the operation, the destroyer John A. Bole was ordered to a position 3 nautical miles off the Communist port of Swatow and found herself surrounded for over five hours by almost 50 armed motorized Chinese junks. The vessels warily watched each other to see who would shoot first, as U.S. aircraft flew attack profiles on the junks, which only added to the hair-trigger situation. There is a theory that John A. Bole’s mission was intended to provoke the Chinese into shooting and give General MacArthur the excuse he was looking for to widen the war into the Chinese sanctuary in Manchuria and to mainland China. If true (which is not proven), the Chinese refused to take the bait. However, the Chinese also abandoned plans to invade Formosa, so the show of force and resolve arguably worked. MacArthur was fired by President Truman as the John A. Bole situation was ongoing (although the order had already been signed on 9 April).

Mines remained the biggest threat to U.S. Navy forces, and on 12 June 1951, destroyer Walke was 60 nautical miles off the beach when she hit one of the hundreds of contact mines that had been deliberately set adrift. The explosion hit berthing compartments, killing 26 Sailors and wounding more than 35. The ship was in danger of sinking, but superb damage control saved her despite the heavy casualties. Four crewmen were awarded the Silver Star for repeatedly entering the damaged compartments to save unconscious or badly injured shipmates. This was the highest loss of U.S. Navy life in a single incident due to enemy action during the Korean War. (Heavy cruiser Saint Paul—CA-73— suffered 30 dead in an accidental turret explosion on 21 April 1952 while bombarding enemy targets.)

For more on the Hwachon Dam attack and significant events in the Korean War from March to July 1951, please see attachment H-061-1.

30th Anniversary of Desert Storm: March–June 1991

In attachment H-061-2, I continue with my personal account of Desert Storm, covering the aftermath period from March to June 1991—which focused on the attempts to establish an improved and enduring U.S. Navy command and control structure in the Central Command Theater—as well as on the growing dismay at the Navy’s losing public relations battle over the service’s role in Desert Shield/Storm. Even more dismaying was the fact that, despite suffering one of the greatest routs in modern military history, Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein not only refused to admit defeat, he actually claimed a great victory. As U.S. forces in the region demobilized and returned to CONUS in pell-mell fashion, Saddam was busy using his surviving forces to slaughter Shia in the south and Kurds in the north who had dared to rise up against him. These groups had done this following U.S. encouragement, only to get no support in the south, and support in the north (Operation Provide Comfort) only after thousands of Kurds were driven from their homes into the mountains. And finally, the Seventh Fleet staff and USS Blue Ridge (LCC-19) returned to Yokosuka after their longest deployment (9.5 months) just in time to see USS Mount Whitney (LCC-20), which had never left the pier in Norfolk, represent the U.S. Navy at the big Desert Storm victory celebration in New York City.

However, I also want to highlight the critical contribution of U.S. Navy sealift, U.S. Navy construction battalions, and U.S. Navy medicine to the success of Desert Storm. Although these did not fall under U.S. Naval Forces Central Command (COMUSNAVCENT) control (which is why I have no personal recollection of their actions), victory in Desert Storm would not have been possible without them.

Sealift in Desert Shield/Desert Storm

With the exception of the World War II Normandy invasion (which had two years to build up and prepare), Operation Desert Shield represented the largest, fastest, and farthest (8,700–nautical mile average voyage) sealift in the history of warfare. The U.S. Navy’s Military Sealift Command (MSC) moved 2.4 million tons of cargo—four times what was moved across the English channel during the D-Day invasion, and six times that of peak force build-up during the Vietnam War. MSC moved more than 95 percent of the combat equipment used to fight and win Desert Storm—over 2,000 tanks, 2,200 armored vehicles, 1,000 helicopters, and hundreds of self-propelled artillery, along with ordnance for hundreds of U.S. Air Force aircraft. In a truly herculean effort, 172 MSC ships were underway on 1 January 1991. Without the U.S. Navy’s control of the sea, largely taken for granted during the war, Operation Desert Storm would not have been possible. For more on Sealift during Desert Shield and Storm, please see attachment H-061-3.

Seabees in Desert Shield/Storm

By the onset of the ground offensive phase of Desert Storm, 2,800 Seabees with 1,375 pieces of construction equipment had deployed to the Arabian Gulf region, the vast majority in forward areas of Saudi Arabia supporting Marine Forces Central Command (MARCENT)/I Marine Expeditionary Force (I MEF). U.S. Navy construction battalion personnel performed absolutely vital work in establishing and maintaining the massive logistics infrastructure capability that enabled the successful U.S. Marine attack into Kuwait, which in turn enabled the U.S. Army’s “end-around” attack.

The first Seabees arrived in time to offload the first maritime preposition ships that arrived in Saudi Arabia on 15 August 1990. Next, two Seabee units commanded by women (a first) and medical personnel built the first and most capable field hospital in the region (Fleet Hospital 5). From then on, additional Navy mobile construction battalions (NMCBs) arrived in a non-stop 7-day/24-hour operation, upgrading roads, airfields, digging wells, building massive tent cities, ammunition and water resupply points, defensive berms and tank barriers, some of which were the largest Seabee projects since the Vietnam War.

Perhaps the Seabees’ finest hours came in the last two weeks before the commencement of the ground offensive: turning a two-lane dirt track into 200 miles of eight- and six-lane highway that connected the coast just south of the Kuwait border with two massive logistics resupply points, also built by the Seabees, further inland. For operational security reasons, this work could not commence until the last possible days, and was completed in time despite the wettest conditions in Saudi Arabia in decades. Seabees worked with the Marines in building a decoy army of fake tanks and artillery pieces, clearing lanes through berms under Iraqi artillery fire, and then following closely behind as the Marines breeched the Iraqi defensive lines in order to establish the I MEF forward headquarters inside Kuwait and upgrade the main supply route into Kuwait.

MARCENT’s initial plan for the assault into Kuwait called for an amphibious landing on the coast of Kuwait, through mine-infested waters and beaches, to ensure adequate logistics support for follow-on Marine attacks. However, it was the MARCENT commander’s (Lieutenant General Walt Boomer) confidence in the Seabees’ ability to execute the massive shift westward of roads and logistics points, and to do it just in time, that alleviated the need for an amphibious assault, no doubt saving many lives and probably ships, too. For more on the Seabee’s contribution, please see attachment H-061-3.

Navy Medicine in Desert Shield/Storm

Navy Medicine played a key role in the preparation and execution of Operation Desert Storm throughout the entire theater, not just afloat. The first significant medical facilities in the theater arrived on board U.S. Navy aircraft carriers, rapidly augmented by the arrival in mid-August 1990 with the “pre-packaged” 500-bed fleet hospital on the afloat pre-position ship M/V Noble Star. Quickly set up with the aid of Navy Seabees, Fleet Hospital 5 was operational by the end of August. The two 1,000-bed hospital ships Mercy (T-AH-19) and Comfort (T-AH-20) arrived by early September. For most of Desert Shield, the fleet hospital and two hospital ships (augmented by even more capacity on arriving amphibious ships) constituted the great majority of medical capability across the entire theater. Two more fleet hospitals would arrive in February 1991 in anticipation of significantly increased casualties arising from the onset of offensive ground combat operations (fortunately the number of casualties was vastly less than anyone anticipated—even so, the three field hospitals treated over 32,000 patients, including military, enemy prisoners, civilian refugees, and expatriates.)

During Desert Shield/Storm, 5,800 Navy corpsmen deployed with their Marine units, and Hospital Corpsman Third Class Anthony Martin was awarded a Silver Star for heroism in tending wounded Marines during an Iraqi mortar barrage. In addition, 6,100 Navy medical personnel, mostly active duty, were deployed to the theater, while an additional 10,400 Navy medical reservists were mobilized to backfill gaps left in hospitals and clinics in the United States when active-duty personnel were quickly sent forward, thus maintaining the high level of care for military personnel and dependents still in the States.

An unsung hero of Desert Shield/Storm was Navy Medical Research Unit (NAMRU) No. 3 in Cairo, which carried on years of research and work on infectious diseases endemic to the region. The Navy forward laboratory, set up on short notice in Jubayl, coupled with Navy preventive medicine teams, and armed with a vast store of knowledge of diseases and ailments in the region, supported all services and ensured that Desert Shield/Storm suffered the fewest casualties per capita due to disease in any such major operation. Fortunately, Navy medicine’s capability to detect, monitor, and treat the effects of biological warfare was not tested, but the Navy Medical Corps made extensive preparations to be ready in the eventuality biological weapons were actually used.

For more on the contributions of Navy medicine to Desert Shield/Storm, see attachment H-061-3. As always, you are welcome to disseminate H-grams further. Back issues enhanced with photographs can be found here. [https://www.history.navy.mil/about-us/leadership/director/directors-corner/hgrams]