H-040-2: Leyte, Ormoc Bay, and Mindoro

Securing Leyte, October–December 1944

Although the Battle of Leyte Gulf on 24–25 October 1944 was a decisive U.S. Navy victory, the battle ashore for control of the island was far from over. Support from the U.S. Navy was still required, which the Japanese made increasingly painful with increased use of kamikaze suicide aircraft. More U.S. ships would be hit, sunk, and damaged during the two months it took to secure Leyte than during the Battle of Leyte Gulf itself. Although no ships as large as the light carrier Princeton (CVL-23) were sunk, several large fleet carriers were put out of action, in some cases for months (although they were quickly replaced by new-construction carriers that continued to join the fleet).

A key complicating factor in securing Leyte was the abysmal weather. The one finished airfield, Tacloban, was initially incapable of handling many aircraft, and alternative airfield construction sites proved to be so muddy that they were virtually unusable. As a result, forward deployment of U.S. Army aircraft to Leyte, to provide organic tactical air support and air defense to the Army forces ashore, was repeatedly delayed. As a result, Admiral Halsey’s Third Fleet carriers remained tethered to the Leyte area to provide the air support that the Army couldn’t. This made the U.S. carriers susceptible to continuing Japanese air attacks as the Japanese continued to funnel more aircraft into the Philippines, albeit mostly with insufficiently trained pilots (although the resort to kamikaze tactics began to mitigate the training problem for the Japanese). In addition, the carrier task groups were vulnerable to typhoons, and suffered significant damage during Typhoon Cobra in December 1944. Despite shortfalls, Japanese aircraft still remained a potent threat, and at times in October and November 1944, Japanese aircraft retained an upper hand at night in the skies around Leyte.

At the last moment, just before the U.S. landings on Leyte, the Japanese army decided it would not send any reinforcements to the island, and would concentrate their defense on the main island of Luzon instead. This caused great consternation in the Japanese navy, which had already committed its forces to the Sho-1 plan to defend the Philippines—and the forces were already moving. So, in effect, the Japanese navy was going to sacrifice itself to attack forces invading an island (Leyte) that the Japanese army didn’t plan to defend (other than by the woefully inadequate ground forces already on the island). This was probably an underrated factor in Vice Admiral Kurita’s decision not to continue into Leyte Gulf, and probably lose his entire force in a pointless mission when he turned away on 25 October 1944.

However, once U.S. forces were ashore on Leyte and began to get bogged down in the mud, Japanese army headquarters in Tokyo overruled the army commander in the Philippines (General Yamashita) and directed that the forces on Leyte be reinforced. This required the Japanese navy to set up “Tokyo Express” runs with troop-carrying destroyers to deliver Japanese soldiers from Luzon to the west coast of Leyte at Ormoc Bay. The Japanese navy would pay dearly for this mission. Many troops were lost to U.S. aircraft on the transit, and were never enough to change the outcome on Leyte. However, they were enough to protract the U.S. Army advance.

Continued Kamikaze Attacks, October–November 1944

On 27 October 1944, fast carrier Task Group 38.2 was operating east of Luzon attacking Japanese airfields on that island and shipping in Manila Bay, damaging the heavy cruiser Nachi and slightly damaging heavy cruiser Ashigara. On 29 October, a kamikaze struck Intrepid (CV-11) on a port side gun position, killing 10 and wounding 6, but the carrier continued operations.

On 30 October 1944, carrier Franklin (CV-13) took a more serious hit from a kamikaze. Three kamikaze attacked. The first hit the water off Franklin’s starboard side. The second crashed through the flight deck into the gallery deck, killing 56 men and wounding 60. The third kamikaze aborted its dive at Franklin and aimed for the light carrier Belleau Wood (CVL-24) instead. Despite being “shot down,” the plane still crashed into the carrier’s flight deck, causing fires and setting off ammunition, killing 92 men and wounding 54 more. Both carriers had to return to the States for repairs.

On 1 November 1944, kamikaze inflicted significant damage on U.S. destroyers supporting operations inside Leyte Gulf. At 0950, the destroyer Claxton (DD-571) was badly damaged by a kamikaze that exploded in the water right alongside, causing serious flooding, killing 5, and wounding 23. The destroyer Ammen (DD-527) was hit by an already-flaming twin-engine Frances bomber just aft of the bridge. The strike destroyed a searchlight and both funnels, with 5 dead and 21 wounded. Nevertheless, Ammen remained battle-worthy and continued to fight for several days. The destroyer Killen (DD-593) was attacked by seven aircraft, downed four, but was hit by a bomb on her port side that killed 15 men. Killen had to return to the States for repair. The destroyer Bush (DD-529) was attacked by several Betty torpedo bombers, shot down several, dodged at least two torpedoes, but avoided being hit except by a shower of shrapnel that wounded two men including the executive officer.

At 1330 on 1 November 1944, destroyer Abner Read (DD-526) was attacked by a Val kamikaze. Although the plane came apart under fire, the bomb went down one of the stacks and detonated in an engine room, while the remains of the plane hit the ship and started a major fire aft. At 1352, a massive internal explosion caused the destroyer to list heavily and begin to sink by the stern. The ship finally went down by 1415 with 22 of her crew. The remainder were rescued by other destroyers, including 187 by the already-damaged Claxton. Claxton was repaired by tender off Leyte and remained in the Philippine action for several months. (Of note, Abner Read’s stern was blown off by a mine off Kiska in the Aleutians on 18 August 1943, with the loss of 71 men. Her crew saved the ship against the odds, and she was repaired with a new stern and returned to service in December 1943. Abner Read’s original stern was located, by chance, during a NOOA research expedition in July 2017).

Demonstrating the risks of carrier task forces operating too long in the same waters, on 2 November 1944, just before midnight, the light cruiser Reno (CL-96), escorting Lexington (CV-16), was hit by two torpedoes on the port side fired by Japanese submarine I-41. One of the torpedoes failed to detonate and had to be defused while stuck in the side of the ship. The other exploded, causing serious damage, with 46 men killed (Morison says only two were killed; the actual number could not be confirmed). Dead in the water with a destroyer left behind to defend her, an unknown Japanese submarine fired three torpedoes at Reno that missed. Reno was towed 700 miles to Ulithi, pumping out prodigious amounts of water to stay afloat, and would eventually return to the States, but would not be repaired in time for the end of the war.

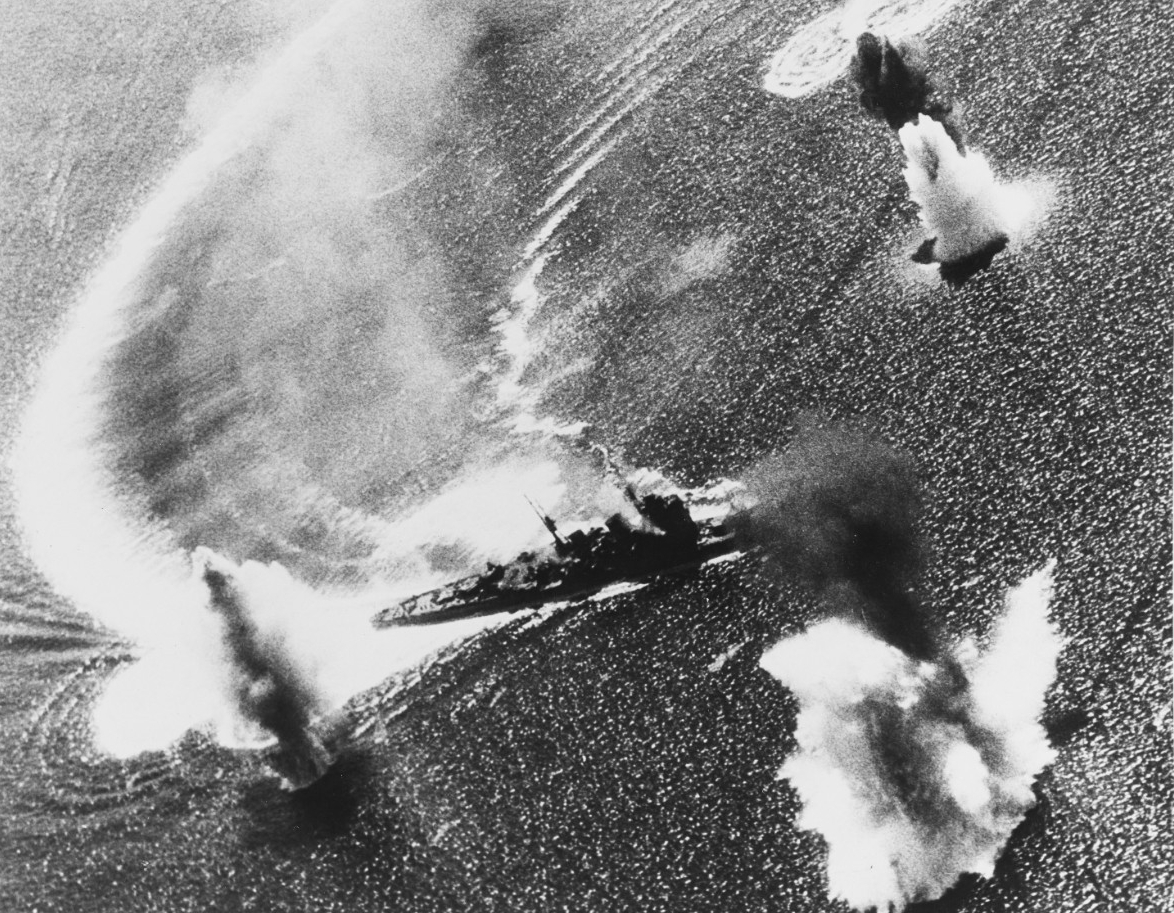

On 5 November 1944, Japanese heavy cruiser Nachi’s luck ran out at she was attacked in Manila Bay by multiple waves of U.S. carrier aircraft from TG 38.3, absorbing numerous bomb and torpedo hits throughout the day as she maneuvered desperately to survive before finally being hit by five torpedoes in that afternoon. These blew her into three parts and she finally sank with 808 crewmen. During concurrent fighter sweeps, the Americans claimed to destroy 439 Japanese aircraft (real number unknown, but probably considerable) for a loss of 25 aircraft in combat and 18 operational losses, along with 18 pilots and crew.

Also on 5 November 1944, the Japanese got some measure of revenge on TG 38.3 when a kamikaze hit the carrier Lexington (CV-16) near the island, causing a major fire that burned out much of the island superstructure. Lexington suffered 50 killed and 132 wounded, but had the fires out in 20 minutes and was able to continue operations.

Meanwhile, Japanese destroyers and transports had been running reinforcement convoys to Ormoc Bay on the west coast of Leyte, eventually getting almost 45,000 troops and 10,000 tons of supplies ashore, adding to the 22,000 troops already there (against 101,000 U.S. troops on the Island by 1 November). However, on 11 November 1944, 347 Task Force 38 carrier aircraft dealt a devastating blow to the operation, sinking four Japanese destroyers and several transports in a convoy en route Ormoc, with the loss of about 10,000 troops, and then sinking two more destroyers as they returned to Manila. However, due to the continuing need for the carriers to support Leyte operations, Admiral Halsey reluctantly recommended on 11 November that planned carrier air strikes on Japan be postponed.

Task Force 38 fast carriers conducted another series of airstrikes on Luzon, Manila Bay, and other Philippine Islands on 13 and 14 November, sinking the light cruiser Kiso, five more destroyers, about seven transports, and claiming destruction of 84 aircraft in the air and on the ground, for the loss of 25 U.S. aircraft, mostly due to ground anti-aircraft fire.

On 25 November, carrier aircraft from Ticonderoga (CV-14) caught up with the heavy cruiser Kumano in Dasol Bay, Luzon, and sank her. Kumano had been badly damaged during the Battle off Samar on 25 October 1944 by a torpedo from destroyer Johnston (DD-557), hit again by two bombs from carrier aircraft on 26 October, and was hit by two torpedoes of 23 fired by four U.S. submarines on 6 November 1944. It took five torpedoes and four bombs from Ticonderoga’s aircraft to finally sink her with 398 of her crew including her captain.

Also on 25 November, the Japanese attacked TF-38 in significant force. The carrier Hancock (CV-19) was hit and lightly damaged by a kamikaze. At 1253, Intrepid (CV-11) was hit by a kamikaze that crashed into a 20-mm gun tub manned by six black stewards who stood their ground and kept firing to the bitter end. The kamikaze started a serious fire on Intrepid, soon followed by a second kamikaze hit. A total of 66 crewmen were killed on Intrepid and 35 wounded. Although the fire was put out in two hours and the carrier remained on station, she subsequently returned to the States for repair. During this raid, another Kamikaze hit the light carrier Cabot (CVL-28) and another almost hit her. Cabot suffered 36 killed and 16 wounded, but was able to return to action following temporary repairs at Ulithi. At 1255, carrier Essex was hit by a kamikaze in a spectacular crash caught on film, which killed 15 crewmen and wounded 44, but only caused superficial damage to the ship. Nevertheless, the damage to the carriers was significant enough to cause the cancellation of strikes on the 26th and temporary withdrawal to a safer distance.

Although the carriers could maneuver to safer waters, the ships defending resupply operations in Leyte Gulf could not. On 18 November, the attack transport Alpine (APA-92) was hit and damaged by a kamikaze while unloading troops, without loss of troops, but five of her crew were killed. On 23 November, the attack transport James O’Hara (APA-90) was also hit, but not significantly damaged.

On 27 November, 25 to 30 Japanese planes attacked U.S. shipping in Leyte Gulf, which was temporarily without fighter cover. Light cruiser St. Louis (CL-49) shot down several planes, dodged a torpedo, but was hit by two kamikaze and seriously damaged, with 16 crewmen lost and 43 wounded. St. Louis had to return to the States for repair. Battleship Colorado (BB-45) continued to pay for being absent during the Pearl Harbor attack (see H-Gram 033) and was hit by two kamikaze, which killed 19 and wounded 72, although the ship only needed forward-area repairs and she would continue to participate in Philippine operations. Light cruiser Montpelier (CL-57) downed several kamikaze before being slightly damaged by one. Battleship Maryland (BB-46) dodged a torpedo from a conventional air raid. However, as sunset approached, Maryland was surprised by a kamikaze that crashed between the forward main battery turrets, piercing several decks, starting fires, causing considerable damage and destroying the medical department, killing 31 and wounded 30. Nevertheless, Maryland continued operations for several more days until returning to Pearl Harbor for repair and extensive refit.

While the attack on Maryland was underway, other kamikaze attacked destroyer Saufley (DD-465), which sustained minor damage, and the destroyer Aulick (DD-569), which suffered severe damage. Aulick was attacked by six kamikaze, one dropped a bomb and crashed close aboard while another clipped the starboard side of the bridge with its wingtip before crashing and exploding near the bow, setting the No. 2 gun and handling room on fire. Several men were killed on the bridge and all told, Aulick suffered 32 dead and 64 wounded.

Ormoc Bay Engagements, November–December 1944

From Leyte Gulf, on the east side of Leyte, getting to Ormoc Bay, on the west side of Leyte, was difficult. The northern way around Leyte was too narrow to safely navigate, while the southern route required a lengthy circuitous path through Surigao Strait and around a number of smaller islands and treacherous shoal water. Up until late November, interdiction of Japanese reinforcement convoys had been exclusively conducted by Army and Navy aircraft. The first night surface sweep of Ormoc Bay took place on 27 November by four U.S. destroyers, Waller (DD-466), Saufley (DD-465), Renshaw (DD-499), and Pringle (DD-477), under the command of Captain Robert H. Smith, commander of Destroyer Squadron 22, aided by a radar-equipped “Black Cat” PBY Catalina flying boat. The force bombarded Japanese positions ashore before the Black Cat detected Japanese submarine (possibly I-46) entering Ormoc Bay. The U.S. destroyers fired on the sub and closed to 40-mm gun range, and the sub briefly returned fire, sinking before Waller could ram it. I-46 was lost with all 112 hands sometime in this period.

On the night of 28–29 November, a force of four U.S. PT boats conducted a night sweep of Ormoc Bay and sank two Japanese patrol craft. On the night of 29–30 November, Captain Smith led four destroyers, Waller, Renshaw, Cony (DD-508), and Conner (DD-582), into Ormoc Bay, but missed a Japanese convoy. On the night of 1–2 December, destroyers Conway (DD-507), Cony, Eaton (DD-510), and Sigourney (DD-502) swept Ormoc Bay, sinking a Japanese freighter.

On 2 December 1944, sightings by aircraft suggested the Japanese were going to make a “Tokyo Express” run into Ormoc Bay. The destroyers Allen M. Sumner (DD-692), with Commander J. C. Zahm embarked in tactical command, Moale (DD-692), and Cooper (DD-695) commenced a night sweep of the bay (all three destroyers were the latest and greatest Sumner-class, with three dual 5-inch guns, ten 21-inch torpedo tubes, and enhanced anti-aircraft weapons and radars). The U.S. ships were under continuous observation and night air attack by Japanese aircraft, which scored a number of near misses on them.

Shortly after midnight, U.S. radar detected two Japanese ships. Summner and Cooper opened fire on the small Japanese destroyer Kuwa, which had large numbers of men topside, and sank her. Moale engaged the small destroyer Take with guns until Sumner and Cooper joined in. However, one of Take’s four torpedoes struck Cooper amidships, breaking her in two and causing her to sink in less than 30 seconds. Over half of Cooper’s crew went down with the ship, including the executive officer. Ten officers and 181 enlisted men were lost. During the night, drifting groups of survivors from Cooper and Kuwa were close enough to exchange words in English. The next day one PBY rescued 56 COOPER survivors and another PBY rescued 48 more, and a few survivors made it to shore.

By this time, U.S. Army commanders had enough of trying to slog through the mud across the mountainous interior of Leyte and decided to conduct an amphibious operation to land the 77th Infantry Division in Ormoc Bay. As a preliminary to this operation, the commander of Destroyer Squadron 5, Captain W. M. Cole, was tasked with transporting troops, vehicles, and ammunition into the bay and land them at a beach that was in the hands of friendly Filipino guerillas. Cole’s force consisted of destroyers Flusser (DD-368), Drayton (DD-366), Lamson (DD-367), and Shaw (DD-373), eight LSM’s and three LCI’s, which departed Leyte Gulf on 4 December and intending to make most of the trip in darkness. The landing went off with minimal trouble at 2248.

Before dawn, as Cole’s force was returning, Drayton was strafed by a Japanese aircraft. At 1100 on 5 December, as the force was transiting Surigao Strait, eight Japanese aircraft attacked. Several were shot down, but one kamikaze hit and sank LSM-20, another extensively damaged LSM-23. The last kamikaze narrowly missed Drayton’s bridge before crashing near the forward 5-inch gun, killing 6 and wounding 12. Destroyers Mugford (DD-389) and Lavallette (DD-448) arrived from Leyte Gulf to augment the escort, and, at 1710, Mugford was hit and damaged by a kamikaze, losing 8 men.

Landings at Ormoc Bay, 7 December 1945

The landing at Ormoc on 7 December proved to be a great success for the U.S. Army and costly for the U.S. Navy. The Ormoc Attack Group (TG 78.3), carrying the 77th Infantry Division, was commanded by Rear Admiral A. D. Struble, and included nine fast destroyer-transports, four LST’s, 27 LCI’s, 12 LSM’s, nine minesweepers, several patrol and control craft, escorted by 12 destroyers. The veteran destroyers Nicholas (DD-449), O’Bannon (DD-450), Fletcher (DD-445), and Lavallette swept ahead of the main force, but were shadowed and reported by Japanese aircraft. Except for some desultory shore battery fire directed without effect at destroyers Barton (DD-722), Laffey (DD-724), and O’Brien (DD-725), the landings at dawn went according to plan and tactical surprise was achieved. Just before 1000, however, Japanese aircraft launched one of their most effective air assaults of the Philippines campaign. The Japanese aircraft conducted a conventional torpedo attack until they were hit, at which point they turned themselves into kamikaze.

Within a space of four minutes, destroyer Mahan (DD-364) was attacked by nine aircraft. The first four were shot down or missed, but the fifth hit Mahan just behind the bridge. The sixth hit Mahan at the waterline and, almost simultaneously, one of the aircraft that had missed overhead turned back and also hit the destroyer, followed by yet another plane, which strafed Mahan. The eighth plane crashed short and the ninth just passed overhead and continued on. Fires quickly spread to the flooding controls, preventing the forward magazines from being flooded, which the commanding officer assessed were in imminent danger. He ordered the ship abandoned. The crew obeyed, but only with great reluctance as they were determined to save their ship. Destroyers Lamson and Walke (DD-723) picked up survivors, and on order from Rear Admiral Struble, Walke scuttled Mahan with gunfire and torpedoes.

The destroyer-transport Ward (APD-16) was hit and heavily damaged by a kamikaze, which started severe fires that were deemed to be out of control. The ship was ordered abandoned, over the objection of some of the crew, who wanted to keep fighting the fires. Like Mahan, Struble ordered Ward to be scuttled and O’Brien was given the order to do so. Before her conversion to a destroyer-transport, Ward (DD-139) had been the destroyer that fired the first shot of the Pacific War, sinking a Japanese midget submarine that was trying to enter Pearl Harbor just before the air attack. On 7 December 1941, William W. Outerbridge was in command of Ward. On 7 December 1944, in an irony of fate, Outerbridge was in command of O’Brien and had the sad distinction and duty to sink his former command, which he carried out.

At 1100 on 7 December 1944, another Japanese air raid developed. Several kamikaze were shot down and others achieved near misses on several U.S. ships. Destroyer-transport Liddle (APD-60) was showered by fragments from a kamikaze that blew up only 30 feet away, but a few minutes later a kamikaze hit Liddle in the bridge from dead ahead, destroying the bridge, combat information center, radio room, and killing the skipper, Lieutenant commander L. C. Brogger, USNR. The executive officer, Lieutenant R. K. Hawes, assumed command and, despite the loss of 36 killed and 22 seriously wounded, brought the ship through the rest of the battle.

Later in the afternoon, destroyer Lamson was serving as the fighter-director destroyer controlling 12 Army P-38 fighters. Lamson directed four of them against a Dinah twin-engine bomber, which then dove on the ship, narrowly missing with a large bomb, before crashing in the sea. Later, a kamikaze hit Lamson on her aft funnel and then crashed into the forward superstructure, staring a fire that engulfed much of the forward part of the ship, killing 21 men, and wounding another 50. Most of those killed were trapped in the No. 1 fireroom when the hatches were jammed by the plane’s bomb. As the fires approached the forward magazine, she was ordered abandoned and scuttled. However, Captain Cole countermanded his own scuttling order and directed the tug ATR-31 to take Lamson under tow, and the badly damaged ship was ultimately saved.

On 10 December 1944, Japanese aircraft attacked into Leyte Gulf again. Destroyer Hughes (DD-410) was hit and damaged by a kamikaze, suffering 23 casualties. Liberty ship William S. Ladd was hit by kamikaze and so badly damaged she had to be abandoned. PT-323 was hit and sunk by two kamikaze and LCT-1075 was sunk in the same attack.

On 11 December 1944, the Japanese attempted their last “Tokyo Express” run to Leyte, and the U.S. Navy commenced a second resupply convoy to the beachhead at Ormoc, a mission that became known as the “Terrible Second.” At around 1700, 10 to 12 Jill bombers attacked and as many as seven concentrated on destroyer Reid (DD-369), all in less than a minute. The first Jill crashed just off Reid’s bow, starting a fire and causing underwater damage. The second Jill was shot down. The third dropped a torpedo that missed and the plane flew away. Others crashed near the ship. The last Jill crashed into Reid in the port quarter between the No. 3 and No. 4 guns, and the bomb penetrated the magazine, which exploded and blew her stern apart. Reid rolled on her beam and sank in two minutes, taking 103 of her crew with her; 152 were rescued. Destroyer Caldwell (DD-605) was narrowly missed by a kamikaze, which passed the ship so closely that the bridge was drenched with gasoline and debris.

The next day on the return passage, Caldwell was hit on the bridge by a kamikaze as she was simultaneously straddled by two bombs that sprayed the ship with shrapnel: 33 of her crew were killed and 40 were wounded, including the commanding officer. Nevertheless, Caldwell continued to shoot at Japanese aircraft and her crew saved the ship. For the Japanese part, the destroyer Uzuki was torpedoed and sunk by PT-490 and PT-492, and destroyer Yuzuki was sunk by U.S. Marine Corps aircraft on the last Leyte “Tokyo Express” run.

Mindoro Landings, December 1944

After Leyte, the island of Mindoro was the next target on General MacArthur’s invasion list, with a landing date set for 15 December 1944 (it had been delayed by the protracted campaign to secure Leyte). By capturing Mindoro, the Manila and Lingayen Gulf areas on Luzon would be in range of U.S. Army Air Forces fighter cover, which would be important for MacArthur’s plan to land at Lingayen and advance to Manila from the north. The Japanese had not seen fit to heavily garrison or fortify Mindoro, so the assault and capture of the island was comparatively easy with few U.S. Army casualties. The same was not true for the U.S. Navy forces that brought the Army to Mindoro.

The Mindoro Attack Group was also under the command of Rear Admiral Struble, embarked on the light cruiser Nashville (CL-43). Nashville had embarked General MacArthur for the landings at Leyte in late October 1944, and had been held out of the Battle of Surigao Strait by Seventh Fleet Commander, Vice Admiral Thomas Kinkaid, for that reason (despite MacArthur wanting to get in the fight). In addition, the attack group embarked 16,500 Army personnel (including 11,878 combat troops) aboard 8 destroyer-transports, 30 LSTs, 12 LSMs, 31 LCIs, supported by 10 large and 7 small minesweepers , 14 other small craft, and 12 escorting destroyers. A Close Covering Group included 1 heavy cruiser, 2 light cruisers, and 7 destroyers, along with a force of 23 PT-boats. A Heavy Covering Group, including 3 older battleships and 6 escort carriers, operated in the Sulu Sea to provide additional support if necessary.

The Mindoro Attack Group was sighted by a Japanese scout aircraft at 0900 on 13 December before it entered the Sulu Sea and, a few hours later, a Japanese kamikaze group was launched. Just after 1500, a lone Val dive-bomber came in by surprise at low altitude, attacking Nashville from astern and hitting her in the superstructure near Struble’s cabin. Both bombs aboard the kamikaze exploded. It was a devastating hit, destroying the flag bridge, combat information center, and communications spaces, and starting fires that caused ready 5-inch and 40-mm ammunition to cook off. By the time fires were brought under control, 133 officers and men had been killed or had died of their wounds, and another 190 were wounded. The U.S. Army commander of the Mindoro force, General Dunckel, was among the wounded, and the dead included his chief of staff as well as Struble’s chief of staff. Struble, Dunckel, and about 50 other staff officers (and several war correspondents) were transferred to destroyer Dashiell (DD-659) to continue the operation, while the badly damaged Nashville returned to Leyte Gulf under her own power.

Later on the 13 December, three kamikaze broke through the fighter cover and attacked the Heavy Covering Group as it entered the Sulu Sea. One of the kamikaze hit destroyer Haraden (DD-585), its wing hitting the bridge before the fuselage impacted the forward funnel and its bomb exploded, showering the aft part of the ship with burning gasoline, and causing her to go dead in the water. The crew of Haraden saved their ship, at a cost of 14 dead and 24 wounded, and she was able to make it back to Leyte under her own power.

On 14 December, the Japanese planned a 186-plane strike on the U.S. force, which was fortunately broken up by U.S. carrier plane sweeps from Task Force 38 (Admiral Halsey’s Third Fleet carriers), and cloud cover. The landings on Mindoro commenced on 15 December as scheduled. Opposition from shore was minimal, but kamikaze attacked the ships, achieving near misses on escort carriers Savo Island (CVE-78) and Marcus Island (CVE-77). Flaming wreckage from a disintegrating kamikaze hit destroyer Ralph Talbot. In the beach area, kamikaze hit LST-738 and LST-472. Destroyer Moale shot down a kamikaze and then came alongside LST-738 to fight the fire. There, she was damaged by a large explosion aboard the LST, which holed Moale, killing one and wounding ten. Moale still was able to rescue 88 of LST-738’s crew after the LST had to be abandoned, and later sunk by U.S. gunfire.

LST-472 (which was participating in her 13th amphibious assault of the war) was attacked by five aircraft, three of which were shot down, but one crashed into the main deck near the superstructure, penetrating the ship and knocking out all her water mains. Unable to control the fires, LST-472 was abandoned with six dead, and also had to be sunk by “friendly” gunfire. Destroyer O’Brien rescued 198 survivors of LST-472.

On 17 December, a kamikaze hit PT-300 off Mindoro, destroying the boat, and killing or wounding all but one aboard, including seriously wounding the PT squadron commander.

After the successful landings on Mindoro, several convoys bringing supplies to the U.S. forces ashore were also attacked by kamikaze. On 21 December, kamikaze hit LST-460 and LST-749. Both were lost, along with 107 soldiers and sailors of the 774 aboard the two vessels. The Liberty ship Juan De Fuca was also hit by a kamikaze, but the damage was not enough to keep her from continuing with the mission. At Dusk, after the remaining 12 LSTs unloaded at Mindoro and commenced a return to Leyte, four kamikaze, initially misidentified as friendly aircraft, attacked. One made a nearly vertical dive on destroyer Newcomb (DD-586). Newcomb’s skipper, Commander I. E. McMillian, later remarked, “An angel of the Lord tapped me on the shoulder and told me to look up.” Due to quick-reaction ship handling, the kamikaze crashed a few yards from the bridge. The other kamikaze were shot down.

The Naval Battle of Mindoro

In a comparatively lame attempt to duplicate their success at Savo Island off Guadalcanal in 1942, the Japanese dispatched a force from Cam Ranh Bay in Japanese-occupied French Indochina (Vietnam) to attack the U.S. landing area at Mindoro. This would prove to be the second-to-last offensive sortie by a Japanese naval force in World War II. Under the command of Rear Admiral Masatomi Kimura, the force consisted of the heavy cruiser Ashigara, the light cruiser Oyodo, destroyer Kasumi (the flagship), and five more destroyers. The forces eluded U.S. reconnaissance for two days as it crossed the South China Sea before it was sighted on 26 December 1944, essentially catching the Americans flat-footed, with the closest significant U.S. surface force, under Rear Admiral Theodore Chandler, over 200 miles away. The initial report by a U.S. Navy Liberator misidentified Ashigara as the super-battleship Yamato, but got the overall force composition correct. In some desperation, virtually every U.S. Army plane on Mindoro—92 fighters, 13 B-25 bombers, and several P-61s—launched a night strike against the Japanese force.

As Kimura’s force approached the Mindoro beachhead area after dark on 26 December, they were opposed by nine U.S. PT boats. Although heavily outgunned, the PT boats fought a running battle with the Japanese. However, the boats suffered more damage from near-miss bombs and strafing by U.S. Army aircraft that mistook them for Japanese in the dark, despite the PT boats’ vain attempts to signal that they were friendly. Kimura’s force cautiously stayed outside the PT boat patrol line, and shelled the beachhead and airfield for about 30 minutes from a distance, inflicting minimal damage and no casualties (a far cry from the bombardments at Guadalcanal). The Liberty ship James H. Breasted was hit and damaged by either Japanese fire or by U.S. aircraft.

As the Japanese were retiring, two PT boats that had been hastily recalled from a guerilla-support mission attacked. PT-221 was caught in Japanese searchlights and accurate gunfire, but managed to escape. In the meantime, PT-223, under the command of Lieutenant (j.g.) Harry E. Griffen, USNR, closed to 4,000 yards and, at 0105 on 27 December, launched two torpedoes. One of these hit and sank the destroyer Kiyoshimo, one of the newest Japanese destroyers. Kiyoshima had been crippled by two direct hits from U.S. Army bombers, but it was the torpedo that sank her, with a loss of 82 of her crew (another Japanese destroyer rescued 169 survivors, and 5 were rescued and captured by U.S. PT boats).

Convoy Uncle 15

On 27 and 28 December 1944, the Mindoro resupply convoy Uncle 15 was repeatedly attacked by kamikaze. At 1012 on 28 December, a group of kamikaze attacked and one hit the Liberty ship John Burke, which was loaded with ammunition. John Burke was obliterated in a massive explosion along with all 68 of her Merchant Marine crew. A kamikaze also hit the Liberty ship William Sharon. The destroyer Wilson (DD-408) came alongside and evacuated William Sharon’s crew, and then on a third attempt, despite exploding ready-use ammo, put firefighters on board and saved the ship. At 1830 on 28 December, LST-750 was struck by an aerial torpedo and had to be scuttled.

When convoy Uncle 15 arrived at Mindoro on the early morning of 30 December, kamikaze aircraft attacked again, and destroyers Gansevoort (DD-608) and Pringle (DD-477), the PT boat tender Orestes (AGP-10), and aviation gasoline tanker Porcupine (IX-126) were all hit in the space of about two minutes. Gansevoort was badly damaged with 34 killed and wounded, while Pringle suffered 11 killed and 20 wounded, and Orestes suffered 45 dead. After Porcupine had been abandoned, the damaged Gansevoort, which had been anchored, was ordered to torpedo the stern of the Porcupine in an attempt to blow it free before the flames reached the aviation gasoline. Although a torpedo hit, it did not have the desired effect, and ultimately the large supply of gasoline went up in flames, at one point imperiling Gansevoort, which had to be hastily re-located. Several hours later, the Liberty ship Hobart Baker was hit by a bomb and sunk off Mindoro.

Over the next days, Liberty ships Simon G. Reed and Juan De Fuca were bombed and sunk off Mindoro. The Liberty ship John Clayton was hit by a bomb and had to be beached to prevent sinking. Finally, at 1730 on 4 January, a kamikaze hit the Liberty ship Lewis L. Dyche, which had a cargo of ammunition and, like John Burke, blew up in a catastrophic explosion that killed all 71 merchant mariners aboard and damaged two PT boats a quarter mile away. By this time, however, the U.S. Lingayen invasion force was on the move and the Japanese kamikaze had more lucrative targets than Liberty ships and LSTs. As costly as the Mindoro invasion was for the U.S. Navy and Merchant Marine, the Japanese lost 103 planes in the Mindoro beachhead area, and probably an equivalent number on the way to Mindoro, along with a brand-new destroyer.