H-035-3: UC-97—Forgotten History in an Unexpected Place

(Originally published in different form in The Sextant, NHHC’s blog, on 26 June 2017)

Storms had churned the water the night before. The sky was overcast, significantly cutting the ambient light below the surface. Moreover, the remote operating vehicle (ROV) malfunctioned, leaving only a difficult-to-control drop camera as the means to positively identify the sonar contact below the workboat of A and T Recovery, the outfit that had previously recovered almost 40 lost U.S. Navy aircraft that are now restored and on display in museums (including NHHC’s National Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola) and airports (including Chicago’s O’Hare and Midway airports) around the country. After much trial and error, and mounting frustration, the sun finally came out, and there she was: on the monitor I could see the stern of UC-97, a sunken World War I German U-boat 200 feet below the surface of Lake Michigan. Wait, Lake Michigan? How in blazes did a World War I German submarine end up here?

In the spring and summer of 1919, UC-97 was the biggest sensation to hit the Great Lakes since possibly the Great Chicago fire of 1871. Hundreds of thousands of people, in virtually every port in the Great Lakes (except for Lake Superior) had lined up to take tours, or just to see, an example of the infernal war machines that had caused U.S. entry into bloody World War I.

America had stood by as millions of soldiers of the great powers of Europe were slaughtered in stalemated trench warfare. However, it was the German’s resort to unrestricted submarine warfare and, in particular, the sinking of the British passenger liner Lusitania in May 1915 with the loss of 1,198 passengers and crew, including 128 American civilians, that outraged many Americans. The killing of soldiers was one thing, but the loss of innocent lives, even if only on a fraction of the scale of carnage of the land war, was too much to ignore and continue business as usual.

When the Germans resumed unrestricted submarine warfare in February 1917 after a hiatus, resulting in the loss of more U.S. merchant ships and civilians to German torpedoes, the United States, under President Woodrow Wilson, declared war on Germany on 6 April 1917. As the United States began to build and train an expeditionary army, the immediate U.S. contribution to the Allied war effort was the provision of over 30 U.S. Navy destroyers to protect convoys from U-boat attacks that were on the verge of knocking Great Britain out of the war. As the trickle of U.S. soldiers sent to western Europe turned into a torrent in early 1918, over two million U.S. soldiers, protected by the U.S. and British navies, safely reached the front and finally turned the tide, convincing German leaders that they could not win the war.

Under the terms of the Armistice that went into effect on 11 November 1918, the Germans were required to surrender their entire navy, which had not been decisively defeated in battle. The German battle fleet steamed to the British base at Scapa Flow, where, in violation of the Armistice, the Germans later scuttled their entire surface fleet in June 1919. The German submarines, eventually 176 of them, were sailed to the British port of Harwich. Although some of the subs were subject to German sabotage, and many suffered from poor maintenance in the final months of the war, they nevertheless represented a level of submarine technology significantly better than that of any other navy in the world, including the U.S. Navy.

The British agreed to allow Allied nations to take some of the submarines to study their technology, with the proviso that the submarines later be destroyed by sinking them in water too deep to salvage so that no other nation would gain an advantage by incorporating German submarines into their fleets. In the meantime, the British vigorously sought to have the submarine outlawed as a weapon of war. Having nearly lost the war because of German submarines, despite having the largest navy in the world by a significant margin, the British pushed hard at various post-war treaty conferences to have submarines banned (like poison gas). No other naval power supported the British position.

Initially the U.S. Navy had little interest in acquiring any of the surrendered German submarines. The Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral William Benson, believed that since their use might soon be outlawed anyway, there was no point. He, and many others, did not believe that the submarine represented a viable form of warfare, and certainly torpedoing merchant ships was not something the U.S. Navy would ever engage in, especially since the Allies, led by the British, were seeking to have some of the German U-boat commanders, and the senior German leaders who authorized the sinking of merchant ships, tried as war criminals. Benson did not want any of his successors or other U.S. naval officers to ever find themselves in the position of the Germans. There was also an arrogant belief in the U.S. Navy that our submarines were superior to those of the Germans, and in some respects (underwater speed and habitability) they were. The German U-boats, however, were superior in the things that made them more effective weapons of war (better periscope optics, better torpedoes, more reliable engines, and, in particular, the ability to submerge far more quickly than any other submarine in the world).

Despite CNO Benson’s lack of enthusiasm, the senior U.S. submarine officer, Captain Thomas Hart (later admiral and commander of the U.S. Asiatic Fleet at the start of World War II), used his personal political connections to convince U.S. government leaders that acquiring several German submarines would be a great addition to the Victory Loan bond drive scheduled for the spring of 1919. The Victory Loan drive, an effort to raise money from American citizens to pay off the government’s huge debt resulting from the war effort, featured captured German military equipment that was sent around the country for public display as an inducement for Americans to reach into their wallets and contribute. The leadership of the Victory Loan drive was convinced that what better German weapon to generate publicity, interest (and contributions) than the dastardly submarines that had led the U.S. to war in the first place? They would be proved right.

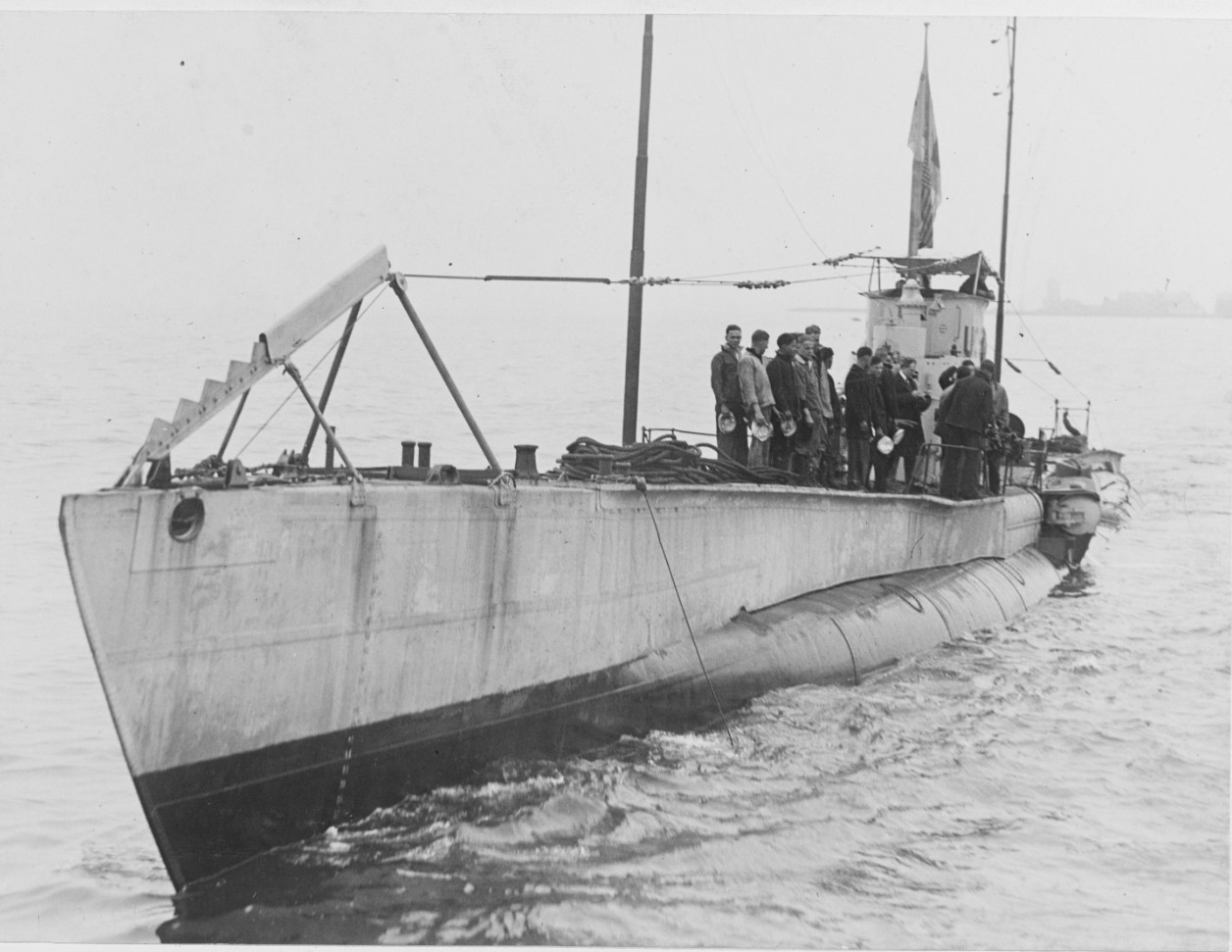

Due to political pressure, the U.S. Navy sent crews to Harwich to bring six of the German submarines to the United States. The subs had been in a state of disrepair for many months. Nevertheless, with extraordinary ingenuity and perseverance, U.S. Navy crews brought all six to the U.S. East Coast in April–May 1919. The U.S. Navy was the only navy that actually sailed German subs under their own power (mostly) to their respective countries (a number actually sank en route other countries). Initially, the Navy sailed four of the submarines, in company with the tender USS Bushnell (AS-2), via a longer and safer southern route across the Atlantic. A fifth submarine, U-111, under the command of Lieutenant Commander Freeland A. Daubin, left three days later due to mechanical issues. U-111’s direct trip across the stormy north Atlantic route, alone, without wireless, and with a power plant of dubious reliability, would cause any of today’s adherents of “operational risk management” to freak out. Nevertheless, U-111 beat all the other subs to New York City for the kick-off of the Victory Loan drive. The sixth U-boat came over later.

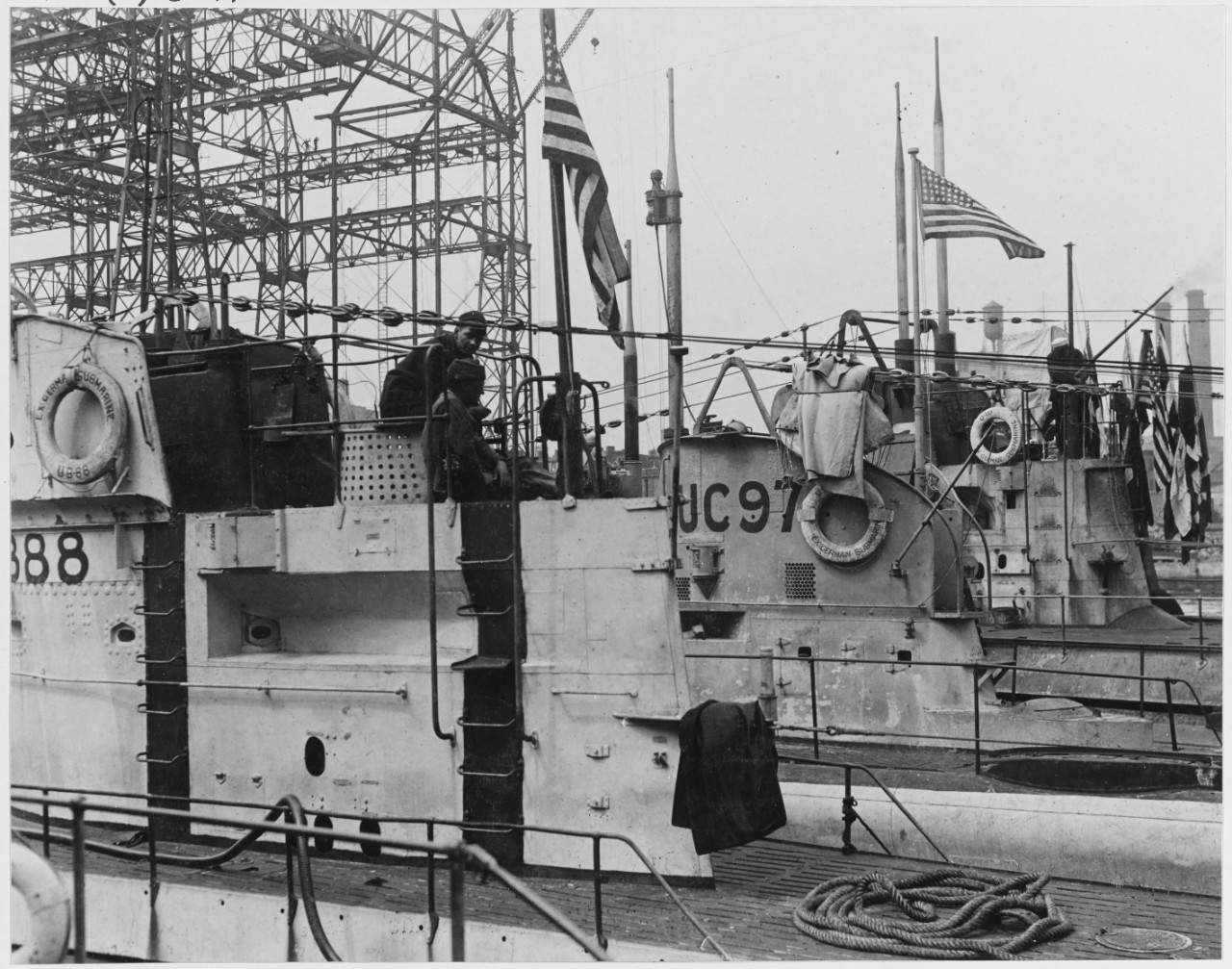

UC-97 stayed in the general vicinity of New York City (which included a somewhat macabre re-enactment/commemoration on the anniversary of the Lusitania sinking), while the other boats visited ports along the U.S. East Coast. All of them were a sensation and attracted many thousands of visitors. At the time, UC-97 was credited with having sunk seven ships with a loss of 50 lives, which added to her sinister, and crowd-pleasing, cachet. The reality was that UC-97 was completed too late to participate in the war, so she actually had no combat record. UC-97 was a UC-III–class submarine, a variant of smaller coastal submarines designed primarily to lay mines rather than attack ships, although she did have three 19.7-inch torpedo tubs (and seven torpedoes) in addition to her six minelaying tubes (and 14 mines) and a 3.4-inch deck gun. UC-97 was 185 feet long, had 491 tons displacement, and a crew of 32 men—a small submarine, even by World War I standards.

After the successful Victory Loan drive (which raised over one billion dollars in the last 24 hours to meet its goal), the Navy decided the submarines would be useful as a recruiting tool. With the “War to End All Wars” having just ended, the Navy needed a new theme to attract Sailors to man the greatly increased U.S. battle fleet as ships authorized in the 1916 and 1917 fleet expansion programs began to come on line. Instead of appealing to patriotism to defeat “the Hun” and save Western civilization, the Navy now turned to “adventure, see the world, and learn high-technology” as a draw (which worked on my grandfather). The U-boats proved to be quite effective as recruiting props.

In May 1919, UB-88 (Lieutenant Commander Joseph L. Nielson, commanding) embarked on an epic recruiting voyage, visiting numerous ports down the U.S. East Coast, into the Gulf of Mexico, up the Mississippi River as far as Memphis, then through the Panama Canal to the U.S. West Coast, where it was later sunk as a target on 3 January 1921 off San Pedro, California, by the USS Wickes (DD-75), commanded by Commander William F. “Bull” Halsey. Meanwhile, UC-97 (Lieutenant Commander Holbrook Gibson, commanding) transited to the Great Lakes, via Halifax, the Saint Lawrence Seaway, and the Welland Canal, between Lake Ontario and Lake Erie, becoming the first submarine of any nation to sail on the Great Lakes.

Both submarines were designed by the Germans for only short coastal missions, and only to last for the duration of the war, so the engineering challenges to these lengthy voyages were profound. Yet it was actually the challenges of accommodating huge crowds (as many as 5,000 people would tour each submarine per day) and additional port cities be added to the itinerary due to political influence that caused UC-97 to fall behind schedule and cancel the Lake Superior portion of the voyage, finishing up in Chicago in August 1919. Nevertheless, the voyage of UC-97 was considered a huge success, and one of the few bright spots of an otherwise dismal 1919. Few today realize how tumultuous 1919 was. Although the “Great War” had ended, over half a million Americans had died from the Spanish Influenza epidemic (which disproportionately killed younger, healthy people), numerous U.S. cities had experienced pro-Bolshevik May Day riots that had turned violent (which was used as a pretext for violent anti-union actions and provoked the first “Red Scare” that threatened American civil liberties), and also some of the most violent race riots in U.S. history, as white mobs in some northern cities gave blacks fleeing southern poverty a deadly reception. By contrast, the voyages of the submarines enjoyed extensive and positive press coverage, and provided a welcome distraction to the national turmoil. Within a year of the finale of her voyage, UC-97 was a forgotten derelict moored on the Chicago River. Like the other five German submarines, UC-97 had been stripped of everything of conceivable value that could be used for study of German submarine technology (engines, periscopes, pumps, etc.), which were scattered about various U.S. Navy commands, laboratories, design bureaus, and defense industries. Finally, in keeping with the Armistice stipulations, UB-88 was sunk as a target on the West Coast. Three of the submarines were sunk as targets off the Virginia Capes as part of Brigadier General Billy Mitchell’s tests of sinking ships with aircraft (U-117 was quickly sunk by bombs from U.S. Navy flying boats, and U-140 and UB-148 were sunk by destroyer gunfire). U-111 sank on her own while under tow off Lynnhaven Inlet, was raised and then repaired enough to be towed to deep water off the Virginia Capes, and scuttled (which made her previous solo trans-Atlantic crossing seem even more miraculous).

UC-97 was in no condition to go very far, so she was towed out into Lake Michigan on 7 June 1921 to be used as a target by the Naval Reserve vessel USS Wilmette (IX-29). (Wilmette was formerly the passenger ferry Eastland, which had capsized in the Chicago River in July 1915, killing 844—the worst loss of life from a single ship in Great Lakes history—and then been raised, repaired, armed, put in Navy service, and then laid up.)

The Navy made a big production out of sinking UC-97. The first shot from one of Wilmette’s four 4-inch guns was fired by Gunner’s Mate J. O. Sabin, who had been credited with firing the first U.S. Navy shot in the Atlantic during World War I. The last shot was fired by Gunner’s Mate A. H. Anderson, who had fired the first torpedo at a U-boat during the war. After being hit by 13 4-inch rounds of 18 fired, UC-97 sank. The famous submarine was then immediately forgotten for decades. The amnesia was so complete that researchers in the 1960s looking for evidence of a German U-boat on the Great Lakes were initially met by total incredulity by the U.S. Navy (including even the U.S. Navy Historical Center, predecessor of NHHC). Multiple attempts to find UC-97 in the 1960s and 1970s failed, and the sub acquired a reputation as one of the most elusive shipwrecks on the Great Lakes. Not until 1992 was she first located by A and T Recovery, which has revisited and observed the wreck site periodically. Although the exact coordinates remain proprietary, A and T Recovery offered to take me out to see this very unique, and largely forgotten, piece of U.S. naval history within distant sight of the skyscrapers of Chicago.

During most of UC-97’s voyage on the Great Lakes, she was under the command of Lieutenant Charles A. Lockwood (who moved up from being executive officer). His career survived a diplomatic spat between Canada and the United States. While visiting Canadian ports and transiting the Welland Canal, UC-97 had refused to fly the Union Jack, which would have been normal for a merchant vessel. Instead, UC-97 flew the U.S. national flag over the Imperial German Navy flag, the standard means to symbolize a captured naval vessel, which resulted in angry feelings among Canadian dock workers and port officials. Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels ultimately had to write a letter informing Canadian authorities that UC-97 was a commissioned vessel in the United States Navy, which made flying the Union Jack inappropriate (the incidents only served to generate even more publicity).

Lockwood would go on to be commander of U.S. submarine forces in the Pacific during World War II after February 1943. Within hours of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral Harold Stark, on his own authority, directed the U.S. Navy to commence immediate unrestricted submarine warfare against Japan, technically a violation of the London Naval Treaty, which had outlawed unrestricted submarine warfare (Japan had abrogated the treaty even before Pearl Harbor). Vice Admiral Lockwood executed the unrestricted policy with an efficiency that even the Germans couldn’t match in either world war, sinking many hundreds of Japanese warships and merchant ships, strangling Japan’s industrial war effort as well as Japan’s ability to resupply far-flung garrisons across the Pacific, and contributing immeasurably to the U.S. Navy’s victory in the Pacific. Many of the technological capabilities of the extraordinarily effective U.S. submarine forces in the Pacific in World War II were a direct result of lessons learned from the study of German technology on board UC-97 and the other surrendered German U-boats.

This piece is based on official U.S. Navy sources, but also owes much to the extensive and original research by Chris Dubbs in his book America’s U-boats: Terror Trophies of World War I (2014). Also of note, UC-97 is protected under the U.S. Sunken Military Craft Act.