H-063-5:The Battle of Ganghwa, Korea, 1871

Background

The Joseon dynasty ruled the area known as Korea from 1392 to 1897, surviving Japanese invasions in 1592–98 (in which Korean “turtle ships,” considered the first armored ships in the world, played a key role) and the Manchu invasions of 1627 and 1636–37. Although technically a vassal state of Qing dynasty China, the Joseon were permitted considerable autonomy. Following the invasions, the Joseon adopted a policy of strict isolationism (hence the moniker for Korea: “the Hermit Kingdom”). As the Joseon observed the humiliation of China and Japan at the hands of European powers (and the United States) with “unequal” treaties, the Joseon policy of isolation grew even stronger. Trade with the outside (besides China) was forbidden. Koreans who had contact with the outside were often executed. Unlike the Japanese, however, the Joseon did not make a practice of killing shipwrecked foreign sailors. As a general rule, such sailors were treated well, but were quickly transported out of Korea to China.

In 1864, the Joseon king died without an heir. In accordance with SOP, the dowager queens (there were three) selected the next king, Gojong, who was a minor (age 11). King Gojon’s father, Heungseon Daewongun, was selected to be regent and ruled for the king until he became an adult. (This is the greatly simplified version of the process.) The Daewongun, translated as “Prince of the Great Court,” was known to Western diplomats as Prince Gung. Although he instituted numerous positive reforms, he vigorously enforced the seclusion policy, to include yet another round of persecuting Korean Catholic converts (as many as 10,000 out of 23,000 were killed in four purges between 1839 and 1866). In early 1866, seven French Catholic missionary priests were beheaded.

On 24 June 1866, the American and Chinese survivors of the U.S.-flag merchant vessel (schooner) Surprise made it ashore on the northwest coast of Korea. They were treated well by the Koreans but quickly hustled out of the country via China on orders of the Daewongun. By 7 July, three French priests, who had survived the purge in Korea, made it back to China to tell their story, prompting the French to put together an expedition under the command of Rear Admiral Pierre-Gustave Roze, which would commence in September 1866.

The General Sherman Incident, August 1866

Into this tense environment, the U.S.-flag merchant schooner General Sherman sailed up the Taedong River in August toward Pyongyang, despite repeated warnings from the Koreans not to do so, in what became known as the General Sherman Incident. When the incident was over, by 2 September, everyone on the ship had been killed. Virtually every account of the General Sherman Incident conflicts with others. The best account actually appears to be in a 1911 book by William Elliot Griffis, Corea, the Hermit Nation. Subsequent accounts frequently mix up the ships involved and numerous other details (and I probably have too).

General Sherman was a centerboard schooner (not a steam vessel, nor an ironclad, as in most accounts). It was well armed for a merchant ship (accounts agree) with a number of 12-pounder cannons, and may have had some sort of armor protection (not confirmed). The ship’s prior history is murky, but it appears to have been originally British owned, possibly named Princess Royal. The British firm Meadows & Co., based in Tianjin, China, financed the voyage and reportedly loaded “cotton cloth, glass, tin plates, and other items” with the intent to open trade with Korea. The Korean version of events is that the real purpose of the voyage was to loot Korean royal tombs northeast of Pyongyang, and there is sufficient circumstantial evidence to suggest this was in fact the real motive. The ship was acquired by an American owner, W.B. Preston, shortly before the voyage commenced, and the ship was then registered as an American-flag vessel under the name General Sherman.

The ship’s captain (Page) and First Mate (Wilson) were Americans. The ship’s American owner, W.B. Preston, was aboard the ship too. Also aboard was a Welsh missionary, Robert Jermain Thomas, who served as an interpreter, and by some accounts had an ulterior motive of his own for the encouraging the vessel to attempt trade with Korea: to spread the Gospel. This would be his second trip into Korea (his first was in 1865). Some accounts say there were two Americans aboard and some say three. Most say four or five “Westerners” were aboard, which would suggest three Americans plus the missionary plus someone else (identified in some accounts as a “British pirate”). The rest of the crew included 13 Chinese and three Malays (by most accounts) plus a Chinese “money changer.” Most accounts indicate there were 20–22 aboard, although some suggest more.

General Sherman probably departed Chefoo, China, on 9 August 1866 and arrived off the western Korean coast on 16 August 1866. As the ship approached Korea, it was assisted by Chinese junks (the Chinese were allowed to trade). Thomas convinced a Chinese pilot, Yu Wen Tai, who he apparently knew from his previous missionary work in Korea, to guide General Sherman up the Taedong River. (Yu Wen Tai, or Yu Wautai in some accounts, appears to have been the only survivor of the incident, presumably getting off General Sherman at some point before things went bad.)

General Sherman sailed to a point on the Taedong River known as Keupsa Gate, where the ship was ordered by local Korean authorities to stop. The Koreans agreed to provide food and provisions to the crew while they consulted with higher authorities. Captain Page ignored the Korean order and proceeded to sail up the river to a point just west of Pyongyang, aided by the fact that the river was running unusually high due to rains and tides. The Koreans again ordered General Sherman to leave, but Captain Page refused. The Governor of Pyongyang, Bak Gyu-su (Park Gyu-su in some accounts), sent his adjutant general, Yi Hyon-ik, to not only provide the ship with food but also order it back to Keupsa Gate while the governor consulted with the Daewongun. The response from the Daewongun was leave or be killed.

At this point, accounts vary widely as to the order of events. General Sherman went even further up the river and ran aground. As the ship was approached by Koreans ashore and on boats, General Sherman fired into a crowd with 12-pounder cannons, killing five (or seven) and wounding seven. Yi Hyon-ik and two of his deputies were also seized as hostages (accounts vary exactly how). Ransom was then demanded for Yi’s release. At some point Yi was rescued, but his two deputies were killed. The ship then sent a boat to sound the river north of Pyongyang (giving some credence to the tomb looting theory). Korean soldiers shot fire arrows and guns at the boat, which returned to the ship. By other accounts, General Sherman ran aground while trying to go back downstream as the river level was falling, and then fired into the crowd in panic. All accounts agree that by 31 August 1866, General Sherman was stuck fast on a sand bar near Yanggak Island in the river off Pyongyang.

Over the next days, skirmishing occurred between the Pyongyang militia and General Sherman, resulting in the death of at least one Korean, with the crew of General Sherman becoming increasingly desperate. On 2 September 1866, the governor of Pyongyang ordered General Sherman be burned with fire rafts; each raft consisted of three small boats lashed together and stuffed with wood, sulfur, and saltpeter. The first two fire rafts were unsuccessful, but the third caused General Sherman to catch fire. Trapped and unable to extinguish the fire, most of General Sherman’s crew died in the flames or drowned trying to escape the burning ship. Two made it to shore and were beaten to death by an angry mob. One of those killed ashore was the missionary Robert Thomas, although accounts vary on exactly how, where, and why he was killed (in some accounts he handed a Bible to his executioner). Thomas had apparently left Bibles on the riverbank during the voyage up the river, and his influence in death turned out to be far greater than in life. Within 15 years, Pyongyang had become the center of Christianity in Korea with over 100 churches.

Many accounts of General Sherman misidentify the ship. Some accounts say General Sherman was a steam side-paddle-wheel armored gunboat. This is actually confused with the USS General Sherman, a “tinclad” side-wheel river gunboat that served in the U.S. Civil War from 1864 to June 1865 on the upper Tennessee River. She was disposed of in 1865 and was not an ocean-going vessel.

Other accounts say General Sherman was an iron-hulled steam screw vessel, formally the British-built Confederate blockade-runner Princess Royal. Princess Royal was forced aground by Union ships off Charleston, South Carolina, on 29 January 1863. She was refloated, repaired, and incorporated into the Union Navy as USS Princess Royal. Armed as a cruiser, she captured several Confederate blockade-runners. Following the war, Princess Royal was decommissioned in July 1865, sold to William F. Weld and Co. of Boston at a public auction in August 1865, and renamed Sherman (after General William Tecumseh Sherman). Over the next years, Sherman made runs from Boston to New York to New Orleans until she sprang a leak and sank off Cape Fear, North Carolina, on 8 January 1874. Some accounts claim Princess Royal, renamed General Sherman, was the ship in the Korean incident. There is even an account that the Koreans repaired General Sherman after she had been burned, and it became for a while their only modern warship, but it was subsequently returned to U.S. custody, sailed to Boston via Cape Horn, and is the same ship that sank in 1874.

The North Koreans have fallen for the Princess Royal/General Sherman story hook, line, and sinker. In fact, the North Korean 2006 commemorative postage stamp, showing a steam screw vessel on fire and labeled General Sherman, is identical to a line drawing of USS Princess Royal. In the 1960s, North Korean propaganda began claiming that Kim Il-sung’s great grandfather, Kim Eung-u, actually led the attack on General Sherman, thereby striking the first blow against American imperialism. (Kim Eung-u would be the great-great-great grandfather of current North Korean “Dear Leader” Kim Jong-un.) There is no evidence for this, but it is now accepted dogma in North Korea. In 1999, the captured intelligence collection ship USS Pueblo (AGER-2) was moved from Wonsan on the east coast to Pyongyang and moored at the location of the burning of General Sherman until 2012, when it was moved to the Fatherland War of Liberation Museum in Pyongyang (see H-Grams 014, 024, and 025 for more on Pueblo).

The First Battle of Ganghwa: The French Expedition, October–November 1866

On 23 September 1866, French ships arrived off the coast of western Korea to conduct surveys in advance of a punitive expedition following the Korean execution of French priests earlier that year. As a result of the survey, Rear Admiral Roze determined that the tides were so widely variable, and the waters so shallow and dangerous, that he could not risk sending his larger ships up the Han River to the Joseon capital of Hanyang (now Seoul). Instead, Roze planned to put troops ashore on Ganghwa Island, which covered the entrance to the Han River. By taking the island, the French could blockade the Han River and force reparations from the Joseon government.

On 11 October 1866, the French force got underway from Chefoo, China, and arrived off Ganghwa Island on 16 October. Roze’s force included the frigate Guerriere. Originally built as a 56-gun sail frigate, Guerriere was extensively modified with the addition of a steam engine and a retractable propeller, which reduced her armament to 34 guns. The force also included two corvettes, two gunboats, and two avisos (dispatch boats) with about 800 troops. The initial landings were made by 170 Fusiliers marins (naval infantry, specially trained for operations ashore) from the French garrison in Yokohama, Japan. The French quickly captured the fortress overlooking the Han, as well as the fortified city of Ganghwa, plus cannons, 8,000 muskets, and boxes of silver and a few of gold. Roze then sent letters demanding reparations, which the Joseon declined to answer.

The French then sent troops across the Salee River, separating Ganghwa Island from the mainland of Korea (not far from Inchon). On 26 October, 120 Fusiliers marins landed on the mainland near the monastery of Munsusansong, which controlled the road to Seoul, but were met with heavy fire from Korean defenders. The French tried again on 7 November, landing 160 Fuseliers marins at Munsusansong, which was vigorously defended by 543 Koreans. The French suffered three killed and 36 wounded before calling a retreat. At this point the French dug in around the city of Ganghwa.

Roze sent another letter, asking for the release of two French missionaries that he believed might still be alive. The French then tried to take a fortified monastery at the southern end of Ganghwa, only to discover the Koreans had been massively reinforcing the position with almost 10,000 men. The French were driven back with many casualties but no deaths. With the Korean refusal to answer any letters, except by mobilizing even more reinforcements, and with winter approaching and word that the two missing missionaries had made it to China, Roze opted to withdraw from Ganghwa Island.

Rear Admiral Roze, believing his force had inflicted more casualties than they had, reported that the murder of the missionaries had been avenged and the Koreans deeply shocked. Most of the French force returned to Yokohama, arriving on 13 January 1867. A majority of French forces in the Far East were then withdrawn as a result of the French suffering heavy casualties in the French intervention in Mexico (1861–67), in which the French suffered about 14,000 killed. The Mexicans suffered far more, but won, and Emperor Maximilian, installed by the French, was captured and executed by the Mexicans in June 1867.

U.S. Response to the General Sherman Incident, 1866–1870

As the French squadron returned from the Korean expedition, the Commander of the U.S. East Indies Squadron, Rear Admiral Henry Bell, first heard reports regarding the General Sherman. The United States had shown little interest in Korea since President Andrew Jackson’s “special confidential agent,” sailing on sloop-of-war Peacock, had recommended in 1832 that the United States try to open trade with the Hermit Kingdom. (See H-Gram 062 for more on Peacock’s diplomatic missions.) From the reports, Rear Admiral Bell was dubious regarding the legality of General Sherman’s actions. Nevertheless, in January 1867, Bell dispatched the large steam screw sloop-of-war Wachusett to investigate. He also recommended to Washington that additional shallow draft steamers and 1,500–2,000 troops be transferred from the North Pacific Squadron to the Far East. (Also in January 1867, the Pacific Mail Steamship Company commenced monthly steamer service between San Francisco and Shanghai.)

Wachusett, commanded by Captain Robert W. Shufeldt, departed Hong Kong on 29 December 1866, coaled in Shanghai, and received orders from Rear Admiral Bell on 23 January 1867 to proceed to Korea and deliver a letter requesting information on General Sherman’s fate. Wachusett embarked General Sherman’s former Chinese pilot (which strongly suggests he was not killed) as well as a missionary interpreter. Shufeldt meant to go to the entrance of the Han River to have the letter delivered to the Joseon capital in Seoul. Instead he wound up at the entrance to the Taedong River (some pilot!). Shufeldt met with a “haughty” Korean dignitary, who informed him that the Koreans considered the crew of General Sherman to be “robbers.” By the time the letter reached Seoul, Shufeldt had been forced to leave by foul weather and worsening ice conditions. Shufeldt was able to determine that the crew of General Sherman was dead, at least most of them, but was not able to find out why.

Through 1867 and into 1868, Washington was focused on relations between the North and the South during the contentious Reconstruction period, ultimately leading to the impeachment of President Andrew Johnson in February 1868. It was also a presidential election year, and as usual, no decisions of consequence could be made. There was no interest in Korea and no orders came regarding the General Sherman. Funding for the U.S. Navy had also gone into steep decline after the Civil War.

In early 1868, the East Indies Squadron was reorganized into the Asiatic Squadron. Rear Admiral Stephen C. Rowan assumed command of the Asiatic Squadron in April 1868 following the death of Rear Admiral Bell in a boating accident at Osaka, Japan, on 11 January 1868. Rowan was a veteran of combat in both the Mexican War and Civil War. He had been in command of the broadside ironclad USS New Ironsides when she was hit and damaged by a spar torpedo mounted on CSS David (one of over 20 semisubmersible torpedo boats operated by the Confederate Navy) off Charleston, South Carolina, on 5 October 1863, several months before the Confederate submarine Hunley sank USS Housatonic off Charleston.

One of Rowan’s first actions was to order Commander John Febiger of the wooden screw sloop-of-war Shenandoah to proceed to Korea to investigate the fate of General Sherman. Commissioned in June 1863 (over a year before Confederate raider CSS Shenandoah was commissioned), Shenandoah weighed in at 1,375 tons, carried a crew of 175, and was armed with one 150-pounder Parrott rifle, two 11-inch Dahlgren smoothbore guns, one 30-pounder Parrott rifle, two 24-pounder rifled howitzers, two 12-pounder rifles, two heavy 12-pounder smoothbore howitzers (and a partridge in a pear tree).

On 11 April 1868, Shenandoah arrived in Korean waters off the Taedong River (repeating Shufeldt’s mistake in understanding that Seoul on the Han River was the seat of Joseon power). Nevertheless, Febiger’s contact with local officials bore some fruit on 1 May when a letter arrived signed by the governor of Pyongyang, Bak Gyu-su. The exact same letter had been sent to China following Shufeldt’s visit, intended for Shufeldt but never received by him. The letter attributed the destruction of General Sherman to a “well-provoked” but unauthorized mob. The “well-provoked” part was true, but Bak had ordered the destruction; the mob had finished off survivors. Nevertheless, Febiger was impressed with the cordial tone of the letter, although Shenandoah was fired on by a shore battery while conducting surveys of the mouth of the Taedong River, but with no damage. Shenandoah departed on 16 May 1868 after learning from another official that, contrary to rumors, there were no survivors of General Sherman.

Rear Admiral Rowan received the report from Febiger and assessed the Korean letter regarding General Sherman’s fate to be accurate. He still considered it an affront to the U.S. flag and was inclined to send a punitive expedition, as had the French. However, Rowan had his hands full with events in Japan as a result of the Boshin War between the Tokugawa shogunate and the Emperor Meiji, as well as different daimyo clans jockeying for position (see H-063-3). In January 1868, a major battle occurred near Kyoto in which the imperial forces won. The defeated shogun sought and received asylum on screw sloop USS Iroquois, then in Osaka Harbor, on 31 January 1868, and was then quickly transferred to a Japanese ship still loyal to the shogun.

In February 1868, soldiers loyal to the Hizen daimyo (which sided with the Emperor) attacked foreigners in the treaty port of Hiogo (near Osaka). A boat from screw sloop USS Oneida was ashore, and one American Sailor was wounded. A force of 15 U.S. Marines pursued the Hizen troops out of the city and were joined in the effort by 50 British troops, members of the French legation guard, and a 150-man Navy force with wheeled boat howitzers from Oneida and Iroquois. Four Japanese steamers in the harbor were captured, but were returned after the imperial government committed to restitution and the officer responsible for firing on the foreigners committed public hara-kiri (ritual suicide) with the captain of Oneida in attendance as the official U.S. observer. In March 1868, a midshipman and 10 sailors in a boat from French corvette Dupleix were attacked near Osaka. The Japanese government sentenced 22 Japanese to death for the attack, and 11 were beheaded before the French Admiral asked that the executions be stopped.

The former Confederate ironclad ram Stonewall also arrived in Yokohama in the spring of 1868 under Japanese flag but with a (very well paid) American crew. Although purchased from the United States by the shogunate, the emperor also claimed the ship. The U.S. consul, Minister Van Valkenburgh, refused to turn over the ironclad in order to maintain neutrality in the Boshin War. In order to save money, the Stonewall’s civilian crew was paid off and replaced with a detachment of sailors from the steam sidewheel gunboat Monocacy. In response to rumors (or intelligence) that an attempt would be made by a Japanese faction to take Stonewall by force, Rear Admiral Rowan ordered Stonewall’s machinery disabled and the crew to General Quarters after midnight, which deterred the boarding effort, if there actually was one planned.

In September 1868, a serious “liberty incident” occurred when two intoxicated U.S. midshipmen from Oneida and four French midshipmen got into an altercation with Japanese police in a “disreputable” district in Hyogo. The police responded with a thrashing by bamboo rods (instead of the usual swords) when challenged. The midshipmen responded by drawing at least one revolver and firing at the police. Luckily no one was hit, and the incident only resulted in a formal apology to the Japanese governor by the U.S. and French ship commanding officers, and not a Japanese demand for execution.

Meanwhile, the Boshin War developed into a naval phase, including the Battle of Miyako Bay and the Battle of Hakodate Bay, which ended the war in 1869. The United States maintained ships on station to observe the shogunate and imperial squadrons. However, much of Rear Admiral Rowan’s time was spent working in concert with British Vice Admiral Sir Henry Keppel in trying to stamp out the venereal disease running rampant through foreign ships in Japan at this time. The material condition of Rowan’s ships was also abysmal, with repeated boiler breakdowns, excessive (unaffordable) coal consumption, and other mechanical issues.

Finally, to cap off a challenging year, Oneida (one of only two vessels Rowan assessed as “serviceable”) got underway from Yokohama en route to Hong Kong on 24 January 1870. In the darkness, Oneida was rammed in the starboard quarter by the much larger British steamer Bombay. As Oneida began to sink, Commander Edward P. Williams tried to sail her to shore, but her steering gear had been ripped away. Oneida’s gig was crushed and another boat smashed by her falling smokestack. Three boats previously lost in a typhoon had not been replaced, leaving only two boats for the crew. In the end, Japanese fishing boats saved 61 sailors, but 125 were lost with the ship, including Commander Williams. A British court of inquiry found the officers of Oneida responsible but blamed the captain of Bombay for not remaining on the scene to rescue survivors. A U.S. court of inquiry placed blame entirely on Bombay.

Rear Admiral Rowan’s tenure as commander of the Asiatic Squadron ended in June 1870. Rowan had requested to return to the United States on his flagship Delaware (renamed from Piscataqua in May 1869) via the newly opened Suez Canal but was ordered to proceed via the Cape of Good Hope. Rowan was promoted to vice admiral upon return but never went to sea again, serving in a series of shore commands until his retirement in 1889 after 63 years of service. Delaware, on the other hand, was decommissioned a month after her return to New York and sank at the pier in 1876.

The Asiatic Squadron in 1871

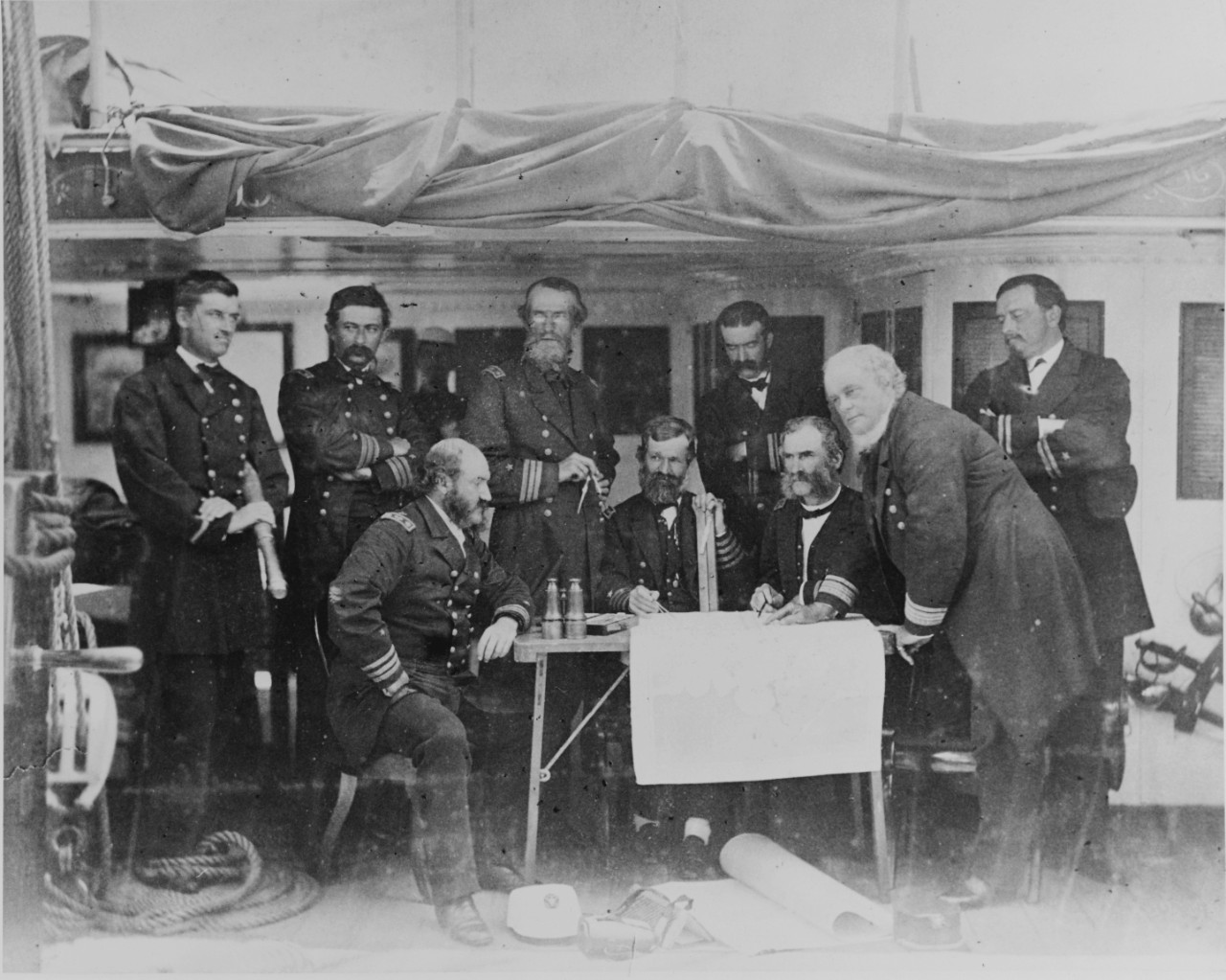

The new commander of the U.S. Asiatic Squadron in 1871 was Rear Admiral John Rodgers, son of Commodore John Rodgers, famous hero of the early American Navy in the Quasi-War with France, both Barbary Wars, and the War of 1812 (he fired the first shot of the War of 1812 while in command of the 44-gun heavy frigate President, sister ship of Constitution). The younger John Rodgers was born in 1812 and became a midshipman in 1828. He commanded an expeditionary Navy-Marine detachment during the Seminole Wars in Florida, and then commanded the North Pacific Exploring and Surveying Expedition (1853–56). Promoted to commander in 1855, he became head of the U.S. Navy’s “Japan Office” in Washington, DC.

When Virginia voted to secede from the Union, Rodgers was sent to Norfolk to save as many ships as possible from being captured; however, most of the ships had already been scuttled and the yard burned. His attempt to destroy the Gosport drydock failed (and it’s still there and in use), and he was captured when the Virginia state militia took the shipyard (and subsequently carted off 1,195 guns for use throughout the Confederacy). Since Virginia hadn’t joined the Confederacy yet, Rodgers was released.

During the Civil War, Rodgers commanded the Western Gunboat Flotilla (which became the Mississippi River Squadron) and supervised the construction of the “Pook Turtles,” the U.S. Navy’s first ironclad warships, armored steam gunboats that served on the Mississippi and other western rivers. In 1862 he was given command of the experimental wooden-hulled ironclad Galena, and then command of the entire James River Flotilla, which was stopped eight miles below Richmond by the Confederate fortifications in the Battle of Drewry’s Bluff in May 1862, during which Galena’s armor was demonstrated to be not thick enough.

In July 1862, Rodgers assumed command of the ironclad monitor Weehawken (an improved version of the original Monitor), and in December 1862, Rodgers and Weehawken survived the same storm that sank Monitor off the Outer Banks of North Carolina. On 17 June 1863, Rodgers and Weehawken defeated and captured the Confederate casemate ironclad ram CSS Atlanta, which won him the “Thanks of Congress” and promotion to commodore. Following an illness, he was given command of the Dictator, designed as an advanced technology sea-going turret monitor, which encountered technological problems during construction, as well as cost overruns, delays, and an unreliable engineering plant (some things never change). Following command of the Boston Navy Yard, he was promoted to rear admiral in December 1869 and given command of the U.S. Asiatic Squadron.

The flagship of the U.S. Asiatic Squadron in 1871 was the wooden steam screw frigate Colorado (named for the river). One of five Franklin-class frigates, Colorado was commissioned in March 1858. At 3,400 tons, with a crew of 674, she was capable of nine knots. Her armament included two 100-pounder rifles, one 11-inch smoothbore, and forty-two 9-inch smoothbore guns, plus two 20-pounder howitzers and six 12-pound wheeled boat howitzers. Colorado served with distinction during the Civil War, including both battles at Fort Fisher (Wilmington, North Carolina) in December 1864 and January 1865, during which her executive officer was Lieutenant George Dewey (future hero of the Spanish-American War in 1898 and the only officer to hold the rank of Admiral of the Navy). Under the command of Captain George H. Cooper, Colorado arrived in the Far East and became the flagship in April 1870.

The Asiatic Squadron in 1871 also had two newly constructed (very rare in the years after the Civil War) wooden steam (twin stack) screw sloops-of-war, which were considered on par in capability with any in the world of that type at the time. (This was an answer to the sorry state of the Asiatic Squadron in the preceding years.)

Alaska was commissioned in December 1869 and was commanded by Commander Homer C. Blake. Alaska was 2,400 tons, with a crew of 273, and capable of 11.5 knots. Her armament included one 11-inch smoothbore gun, six 8-inch smoothbore guns, one 60-pounder (5.3-inch) Parrott rifle, and two 20-pounder guns. She got underway from New York in April 1870 and transited to the Far East in company with Colorado.

The wooden steam (two stacks) screw sloop-of-war Benicia was commissioned in December 1869. Benicia was 2,400 tons, with a crew of 291, and capable of 11.5 knots. Her armament included one 11-inch smoothbore gun, ten 9-inch smoothbore guns, one 60-pounder rifle, and two 20-pounder breech-loading guns. Under the command of Commander S. Nicholson, Benicia arrived in the Asiatic Squadron in March 1870.

There were three gunboats in the Asiatic Squadron. Ashuelot (see Formosa Expedition H063.4) needed extensive dock work and was unavailable for the Korean expedition. Monocacy was a sidewheel gunboat completed in 1866. She was 1,392 tons, had a crew of 159, a top speed of 11.2 knots, and was armed with six guns. She participated in the opening of the Japanese ports of Osaka and Hyogo in 1868, conducted a survey of Japan’s Inland Sea, and sailed up the Yangtze River in China making charts.

The gunboat Palos was an iron-hulled screw tug commissioned in 1870 and modified to carry two guns. In 1871, she carried six 24-pounder howitzers. She was only 420 tons and capable of 10.35 knots. During her transit to the Far East, Palos gained the distinction of the first U.S. warship to transit the Suez Canal, on 11–13 August 1870. (The Suez Canal officially opened on 17 November 1869.)

One officer of particular note serving in the Asiatic Squadron aboard Benicia was Lieutenant Commander Winfield Scott Schley. Schley graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1860 and participated in multiple battles during the Civil War in the Western Gulf Squadron and on the Mississippi. In 1864, he was sent to the Pacific to serve as executive officer on sidewheel gunboat Wateree. Wateree almost didn’t make it around Cape Horn and was badly battered. After the war, Wateree operated along the west coast of Central and South America. Schley participated in operations ashore in La Union, El Salvador, to protect U.S. interests during a revolution. In 1866, at the request of Peruvian authorities, Wateree played a key role in the suppression of a rebellion by Chinese laborers in the Chincha Islands. (Known as “coolies” at the time, a term that is now a pejorative, the Chinese were virtual slaves, laboring under the most appalling conditions mining guano. Almost none survived their term of indentured servitude and the mortality rate on ships bringing Chinese laborers to Peru was 40 percent, rivaling that of the worst of the African slave trade. The Chinese who were imported to American to work on the railroads didn’t fare much better.)

After Schley detached, Wateree was driven 400 yards ashore during an earthquake (the most devastating ever recorded in South America) and tsunami at Arica, Peru, (now in Chile) on 13 August 1868. Only one man from Wateree died ashore, but the accompanying stores ship Fredonia was destroyed with a loss of 27 crewmen (five survived). The ships were in Arica to avoid a yellow fever outbreak in Callao, Peru.

The 1871 Korean Expedition

One person who had been particularly outraged by the General Sherman Incident was Secretary of State William H. Seward. Seward is more commonly known for his purchase of Alaska (denigrated at the time as “Seward’s Folly,” although his push for a Korean punitive expedition would later be known as “Seward’s real folly”). Seward was out of office with the change of administrations in the spring of 1869, but the former U.S. consul in Shanghai and current secretary of state, Hamilton Fish, took up the cause. Fish directed the U.S. minister to China, Frederick Low, to enlist and accompany the Asiatic Squadron on a mission to open Korea for trade, or, failing that, to punish the Koreans.

With a more operationally capable force than Rear Admiral Rowan had had, Rear Admiral Rodgers was much more inclined to pursue such an expedition to Korea. Low and Rodgers spent almost a year gathering and digesting every bit of intelligence they could find on Korea, which actually proved quite difficult due to Korea’s isolation (some things never change). Rodgers was able to obtain a useful hydrographic chart prepared during French Rear Admiral Roze’s expedition to Ganghwa in 1866. No other Western nations showed an interest in joining the expedition (perhaps having actually learned from the French experience). The attempt to gather allies and information was not especially discreet, so the Chinese were well aware of a forthcoming U.S. expedition and passed that on to the Koreans.

The flagship Colorado and gunboat Palos arrived at Woosong, China, in April 1871 to embark Minister Low, as well as five shipwrecked Korean sailors to be returned to Korea as a gesture of goodwill. However, the Koreans were so fearful that they would be executed on return for being tainted by the outside world that Rodgers left them in Nagasaki. The rest of the Asiatic Squadron rendezvoused at Nagasaki, except for gunboat Ashuelot, which required extensive repairs and was deemed unfit for service without dockyard work. All but 20 of Ashuelot’s crew were subsequently distributed throughout the rest of the squadron.

On 16 May 1871, Rodger’s squadron departed Nagasaki, Japan, for the west coast of Korea. Gunboat Monocacy was damaged in a gale but continued ahead to the rendezvous point in the Yellow Sea. The squadron was then delayed by thick fog. On 24 May, the force arrived at Roze Roads (named after the French admiral of the 1866 expedition). Palos was sent ahead with four steam launches from the other ships to sound and survey the approaches to the mouth of the Salee River. In the meantime, the other four ships waited at Roze Roads while the Marine detachment, under Captain McLane Tilton, USMC, conducted extensive infantry battle drills. Minister Low also drafted a letter regarding the purpose of the expedition (trade) and provided it to local Korean authorities. After four days, the Palos and launches returned to report the channel was navigable to an anchorage (Boisee) at the mouth of the Salee River, but the larger ships could not go up the Salee River. Fog delayed the ships arrival at Boisee until 30 May.

Upon arrival at Boisee, a Korean junk arrived and reported that Low’s letter had been delivered and three emissaries would arrive to parley. Low declined to meet them when he determined they were too junior. He sent word back that the U.S. force had no hostile intent but would only negotiate with diplomats of the highest level. Low also stated that boats would need to survey the Salee River, and that forts on both sides of the river should be ordered not to fire on them.

The Salee River runs north–south and connects the estuary near present day Inchon (south) with the Han River (north), which runs east–west at that point. The Salee River separates the island of Ganghwa to the west from the mainland of Korea to the east. On the Ganghwa side of the river were several Korean forts and gun batteries overlooking the river. On the mainland side was one larger fort across the river from the northernmost Ganghwa fort. Near the location of the last forts, the river makes a sharp jog to the east, and then loops back to the west, before resuming its north–south track.

The (Second) Battle of Ganghwa, June 1871

On 1 June 1871, the steam launches entered the Salee River to conduct the survey, covered by the gunboats Monocacy and Palos. The survey operation was commanded by Commander Homer Blake (commanding officer of Alaska but embarked on Palos). It was immediately noted that all the Korean forts appeared fully manned with flags and banners flying. The strong current played havoc with the survey boats, but they continued to press northward into the river and past the first two forts to the west.

Without warning, Korean batteries fired on the survey boats. This was in accord with Korean rules of engagement that forbid any foreign vessels from entering the Salee or Han rivers, as the Han was the direct path to Hanyang (now Seoul), the Joseon dynasty capital. The survey launches immediately manned their boat howitzers and returned fire. The gunboats Monocacy and Palos drew up and added their heavier firepower to the barrage on the forts. The current actually swept all the launches and gunboats past the Korean forts. Palos was damaged by the muzzle blasts and recoil of her own guns. Monocacy struck an uncharted rock, which put a hole in her hull. Two sailors were wounded. Commander Blake ordered the force to anchor until the tide turned, while continuing to fire on the forts until it appeared the Koreans had abandoned them. The steam launches expended almost all their ammunition in the bombardment. Blake then brought the force back out of the river, firing at the forts as they went, with no response from the Koreans.

Rear Admiral Rodgers and Minister Low immediately wanted to take punitive action, but then had second thoughts, concluding the forts possibly opened fire on the authority of lower ranking officers without the approval of the Korean government. The Americans were able to establish communications with Koreans ashore by means of a flagpole on an island to which messages were attached. Rear Admiral Rodgers gave the Koreans 10 days to commence negotiations and demanded an apology. Monocacy was repaired by letting the tide ebb as she was over a shallow mudbank, then patching the hole before the incoming tide lifted her off. Two 9-inch smoothbore guns were then offloaded from flagship Colorado to Monocacy to give her more firepower.

While awaiting an authoritative Korean response (the locals kept signaling some Korean version of “Yankee go home”), Rodgers and his commanders drew up a battle plan. Palos and Monocacy remained fully manned in order to provide gunfire support. Colorado, Alaska, and Benicia then contributed enough men to form an infantry battalion, artillery battery, and hospital parties. All told, 109 Marines and 542 sailors formed the landing party, while another 118 sailors manned four steam launches. Commander Blake, once again embarked on Palos, was given overall command of the landing and support force, while the skipper of Benicia, Commander Lewis A. Kimberly, was given command of the landing force.

On 10 June 1871, with no satisfactory reply from the Koreans, Commander Blake gave the order to execute in accordance with the preapproved plan. Colorado’s steam launches lead the way into the Salee River, taking soundings as they went. Monocacy followed to provide support with her enhanced armament. Palos then followed, towing 22 small boats with the landing party embarked. Steam launches from Alaska and Benicia brought up the rear.

Just before noon, Monocacy opened fire on a Korean battery on the west bank, which was apparently abandoned. Monocacy then took the southernmost fort (Ch’o ji jin/Fort Du Conde) on the west bank under fire. The Koreans responded with heavy fire at 300 yards, but most rounds went high, causing minor damage to rigging. Monocacy’s skipper, Commander Edward P. McCrea, ordered his ship to anchor above the fort and fire until the fort was silenced.

The Korean fire had been more vigorous than expected, so Commander Blake changed the location of the landing to a less exposed spot. However, when the landing party jumped off the boats, they sank into knee-high mud, and the march ashore turned into a slog under the June sun—and would have had severe consequences (like those faced by the British and French at the Taku Forts in 1859) had not most of the Koreans manning Ch’o ji jin not already fled. The Marines occupied the fort with relative ease, although the same could not be said for getting the seven 12-pounder wheeled howitzers through the muck (75–80 men per gun had to pull). Commander Kimberly opted not to advance further as his men were completely exhausted by the mud. (Note, I use the Korean names for the forts when known because the American names assigned after the battle just cause confusion.)

In the meantime, Palos maneuvered to take the second fort (Tokchin/Fort Monocacy) on the west bank under fire until she stuck fast on an uncharted rock. As the sun began to set and Palos was still aground, Commander Blake transferred to Monocacy. Fort Tokchin then took Monocacy under fire, but Monocacy responded with accurate fire at 500 yards, silencing the fort. Palos got off the rock overnight, but her rudder was jammed and her steam pumps could barely keep up with the leaks. She was out of the battle. Monocacy dragged her anchor overnight and scraped her hull on rocks, fortunately without significant damage.

On the morning of 11 June 1871, the landing force completed the demolition of Ch’o ji jin and commenced the march on Tokchin, the second fort to the north. Monocacy bombarded the fort and disrupted apparent Korean attempts at counterattack. The Marines then occupied Tokchin without opposition and demolished it. The combined Marine-Navy advance continued up the west side of the river through very difficult terrain under a scorching sun. Korean infantry attempted ambushes and skirmished with the Marines but were driven off by a howitzer that sailors had to carry up a steep slope. By noon, the Marines and sailors were within 150 yards of the primary objective, the fortress of Kwangsong-chin (Fort McKee), which had fired the first shot on 1 June and was the most formidable of the forts.

Just after noon, after determining the Korean defenders only had single-shot weapons, 350 U.S. sailors and Marines, supported by two howitzers, charged down into the gully outside the fort and up the other side. The steep slope might otherwise have been impassable had it not been chewed up by shellfire, creating handholds. Korean fire was mostly inaccurate, and the defenders resorted to throwing stones. The first American over the parapet was landsman Seth Allen of Colorado, who was killed. He was followed by Lieutenant Hugh McKee, who was mortally wounded by gunfire and spears. But the approximately 300 Koreans in the fort could not keep up with the rush of Marines and sailors over the parapet, and the battle turned into a vicious 15-minute close-quarters fight with spears, swords, and stones against cutlasses, bayonets, rifle butts, and revolvers.

The commander of the fort, General Eo Jae-yeon, was killed by a Marine sharpshooter during the hand-to-hand fighting. The Koreans broke and fled for the river (General Eo had deliberately burned a bridge over a ravine to preclude escape) but in doing so exposed themselves to withering fire from two directions from Americans outside the fort; many were cut down by the two howitzers, others drowned in the river. Although the Koreans in the fort fought bravely, their weapons were hopelessly outdated (some of their matchlocks were a couple centuries old) and no match for the Remington rifles carried by the Americans.

At this point it was discovered that a Korean infantry force estimated at four or five thousand men was preparing a counterattack. The wheeled boat howitzers kept the Korean force at bay until ammunition ran low. Monocacy responded to emergency signal by sending a boatload of howitzer shells ashore. Two half-hearted approaches by the Koreans were repelled. When the Koreans realized the fort had fallen, they opted to break off the engagement. As the American flag went up over the fort, the crew of Monocacy responded with a rousing cheer, which was cut short when the Korean fort on the opposite side of the river opened fire. Monocacy turned her guns on the offending fort (Fort Palos) until the defenders were seen to flee. After being informed of the victory, Rear Admiral Rodgers ordered the force to remain in the fortress of Kwangsong-chin overnight to demonstrate to the Koreans that the United States could hold the fort. At dawn on 12 June, the U.S. force withdrew back to the ships.

Rear Admiral Rodger’s force suffered three dead and 10 wounded. Additional personnel ashore and aboard ship, especially Monocacy, suffered sunstroke but survived. The two gunboats were sufficiently damaged by hitting rocks as to require additional repair. Korean casualties were far higher, with 243 bodies counted. The number killed by naval gunfire and in the aborted counterattack is unknown. Commander Kimberly’s adjutant, Lieutenant Commander Winfield Schley, estimated total Korean dead at 350. Twenty Koreans were captured, many of whom were wounded. Many Koreans committed suicide to avoid being captured. Forty Korean cannons (from 2-pounders to 24-pounders) were captured or destroyed. The forts on the west bank of the Salee were blown up, as was an extensive quantity of munitions and stores. The Americans captured 47 flags and standards, including the sujagi (general officer’s flag) of General Eo.

After the battle, Minister Low attempted to continue the flagpole conversation with the local officials ashore, even succeeding in getting a lengthy letter addressed to the king to the shore, which explained the situation. The letter was returned with a note that said the king was so angry at the United States that the official didn’t dare deliver it. The Korean position was that had the United States not forced their way into the Salee River, the battle would not have happened. The U.S. position (which was the same as that of European imperial and colonial powers of the day) was that ships of White people’s nations had every right to steam around in the territorial waters of non-White nations without being fired upon.

At the end of June 1871, the German frigate Hertha showed up from Chefoo, China, having heard that Rear Admiral Rodger’s squadron had been destroyed (i.e., first reports are always wrong) and the Hertha was searching for survivors, an appreciated but unnecessary gesture.

As the Koreans refused to budge, Rear Admiral Rodgers determined that waiting around any longer was a waste of time, and without his gunboats, he was in no position to continue the attack. On 3 July 1871, Rear Admiral Rodger’s squadron departed for Chefoo. Although the Koreans had been punished for being bad, and many had been killed, little else had been accomplished. In his after action letter to Secretary of the Navy George Robeson, Rear Admiral Rodgers stated that only the occupation of Seoul would cause the king of Korea to admit defeat, and with 3,000, or better yet, 5,000 troops, Rodgers could do it. With the United States still reeling from the carnage of the Civil War, even Rodgers understood the United States would not make that commitment for a faraway country like Korea. The United States would not have a trade treaty with Korea until 1882, the Treaty of Peace, Amity, Commerce and Navigation, also known as the Shufeldt Treaty. The treaty was negotiated by none other than Commodore Robert Shufeldt, who in 1866 had served as commanding officer of Wachusett (the first ship to react to the loss of General Sherman).

The Battle of Ganghwa resulted in the awarding of 15 Medals of Honor, nine to Navy personnel and six to Marines, none posthumously. These were the first Medals of Honor awarded for overseas service against a foreign adversary. At the time, the Medal of Honor was the only award for valor and could be awarded for combat and noncombat courage. Standards for the award became more rigorous over the years, especially beginning in World War II. Nevertheless, for sailors to charge the ramparts of a heavily manned and defended fort, armed with rifle and bayonet, took a high degree of courage. Most of the Medals of Honor were awarded for the hand-to-hand combat inside the last fort. Carpenter Cyrus Freeman Hayden, the color bearer for Colorado, was awarded the Medal of Honor for planting the flag on the ramparts while under heavy fire (the flag had multiple bullet holes). Marine Private James Dougherty shot and killed Korean General Eo Jae-yeon, and Corporal Charles Brown captured Eo’s standard (sujagi). The only person to receive a medal for action outside the last fort was Ordinary Seaman John Andrews of Benicia for standing in the open on Benicia’s launch taking soundings “with coolness and accuracy” despite being under heavy fire. Interestingly, Lieutenant Hugh McKee, who personally led the attack into the fort, and was mortally wounded as a result, was not awarded a Medal of Honor. However, three U.S. Navy ships were named after him: Dahlgren-class torpedo boat TB-18 (1898–1912), Wickes-class destroyer DD-87 (1918–1936), and Fletcher-class destroyer DD-575 (1943–46, 11 Battle Stars in World War II).

Aftermath

After the Battle of Ganghwa, Colorado remained in the Asiatic Squadron until March of 1873. She met a rather ignominious fate. After being sold in 1885, she was waiting to be broken up at Port Washington (Long Island) when she caught fire and sank. Not only that, but the fire spread and burned five other decommissioned U.S. Navy ships; the Minnesota, Susquehanna, South Carolina, Iowa, and Congress all burned and sank (according to the New York Times 22 August 1885 issue, although some of the names are incorrect).

Alaska departed from Hong Kong to return to the United States in October 1872. She was subsequently assigned to the European Squadron. On 30 November 1873, Alaska and the rest of the squadron departed station and joined with the South Atlantic and Home Squadrons off Cuba in reaction to the Spanish capture of the American sidewheel steamship Virginius, hired by Cuban rebels to run guns. The Spanish executed 53 of the crew, including eight Americans (one of which was the American master) by firing squad. The Spanish then decapitated them and trampled the bodies with horses for good measure. Intervention by the Americans and the British (who sent the sloop HMS Niobe) resulted in 91 being spared. War was averted, but this incident was a key event eventually leading to the Spanish-American War.

In December 1875, the U.S. ambassador to Liberia (James Milton Turner, the first African American U.S. ambassador) requested a U.S. warship as a show of force to avert a war between the indigenous Grebo people and descendants of freed Black American slaves, who had established an independent nation of Liberia in 1847 (not recognized by the United States until 1862) and a de facto U.S. colony during much of the 1800s. Alaska arrived in February 1876. The show of force worked and a negotiated solution was found. Alaska then served in the Pacific Squadron from 1878 to 1883, reacting to Alaskan native unrest at Sitka, Alaska, in 1899. On 14 September 1881, under the command of George Belknap and at anchor off Callao, Peru, Alaska suffered a fire in the boiler room. Two sailors were awarded the Medal of Honor for fighting the fire. It was the second Medal of Honor for 1st Class Fireman John Lafferty (also spelled Laverty), whose first was during the Civil War during a daring attempt to destroy the Confederate ram CSS Albemarle). With her material condition badly deteriorated, Alaska was decommissioned in 1883.

Benicia subsequently served in the North Pacific Squadron until she was decommissioned in 1875, after only six years of service, during a nadir of U.S. Navy funding and capability. In November 1874, Benicia had the distinction of taking King Kalakaua (the last king of Hawaii) to San Francisco (following the riots of 1874), leading to the Reciprocity Treaty of 1875 and exclusive use of Pearl Harbor by the U.S. Navy.

Monocacy would continue to serve in the Far East until 1903 (and will appear in some future H-grams).

Palos would continue to serve in the Asiatic Squadron until 1893. During anti-foreign riots in 1891, Palos transited 600 miles up the Yangtze River to Hankow to protect American interests in China.

Rear Admiral Rodgers returned to the United States after his tour in command of the Asiatic Squadron and assumed command of Mare Island. He served as president of the U.S. Naval Institute from 1879 to 1881. He died in 1882 as superintendent of the U.S. Naval Observatory.

After serving on Benicia, Lieutenant Commander Schley served as head of modern languages at the Naval Academy. As commodore of the “Flying Squadron,” Schley would be the victor in the decisive defeat of the Spanish Squadron in the Battle of Santiago in July 1898, during the Spanish-American War (see H-gram 020).

The Third Battle of Ganghwa, 1875

The Japanese had better luck than the French or Americans. In the 1870s, tensions were rising between Korea and Japan over the Koreans refusal to recognize the Japanese emperor (Meiji) as the equal of the Chinese emperor (now there’s an excuse for war!). Emulating the United States and European powers, the Imperial Japanese Navy steam screw gunboat Unyo was conducting survey operations near Ganghwa Island on 20 September 1875. This appeared to be a deliberate provocation. The Korean forts fired on the Japanese. The Japanese put troops ashore, burned some houses, captured weapons, and killed about 35 Korean soldiers in exchange for two Japanese wounded. The Japanese demanded an official apology, which they got. This outcome was significantly aided by the fact that the Daewongun had been forced into retirement by his son, King Gojong, who was more open to interacting with the outside world. The Daewongun’s forced retirement was in part due to the decisive defeat of Korean forces in the second Battle of Ganghwa with the United States and the recognition by the king and other senior leaders of the Joseon government that Korea was in desperate need of modern weaponry. As a result of the Japanese incursion, the Treaty of Ganghwa was signed in 1876, making Japan the first outside nation (besides China) allowed to trade with Korea. The Japanese would eventually turn Korea into a colony in 1910 that they would rule with extreme brutality.

Sujagi and Flags

By U.S. law (issued by President James K. Polk in 1849), the U.S. Naval Academy is the repository for enemy flags and battle standards captured by the U.S. Navy. General Eo’s sujagi (literally, general officer’s flag) was kept at the U.S. Naval Academy Museum until it was returned to South Korea on a 10-year loan in 2007. This is the only sujagi still in existence. It is still in South Korea at the National Palace Museum of Korea. And for you math majors, yes we are in year 14 of the 10-year loan, as the Koreans are reluctant to give it back. In December 2017, faded British ensigns from the War of 1812 on display in Mahan Hall for many years were taken down for conservation. The big surprise was that behind the British flags were the flags and banners captured from the Korean forts in 1871 and missing for many years (since at least 1913). Because the Korean flags were covered, their colors are still in extraordinary condition. As the U.S. Naval Academy Museum is part of the Naval History and Heritage Command museum system, valuable artifacts are no longer kept on display until they are irreparably damaged by UV light, as in the past. NHHC also has a state-of-the-art Smithsonian-caliber conservation laboratory where some artifacts that are not too far gone can be restored.

Sources include: Far China Station: The U.S. Navy in Asian Waters 1800–1898, by Robert Erwin Johnson: Naval Institute Press, 2013; “Korean and American Memory of the Five Years Crisis, 1866–1871,” by James P. Podgorski, MA thesis, Purdue University, May 2020; Corea, the Hermit Nation, by William Elliot Griffis: W.H. Allen & Co., London, 1911 (first published 1882); “Our First Korean War,” by Midshipman Second Class Bryce Kleinman, U.S. Naval Institute Naval History Blog, 3 July 2019; The Savage Wars of Peace: Small Wars and the Rise of American Power, by Max Boot: Basic Book, Persus Book Group, 2002; “SS General Sherman (+1866),” wrecksite.eu; “SS General Sherman Incident,” global security.org; “Not USS General Sherman,” by Mark Peterson, Korea Times, 19 January 2020; “General Sherman Incident,” New World Encyclopedia; “The Forgotten Korean War (of 1871),” by Sebastien Roblin, The National Interest, 20 December 2020; Forty-Five Years Under the Flag, by Winfield Scott Schley, Rear Admiral, USN: D. Appleton and Co., New York, 1904; “Korea, US and General Sherman Incident,” by Kyung Moon Hwang, Korea Times, Korea Times, 16 August 2017; NHHC Dictionary of American Fighting Ships (DANFS).