H-053-1: The End of the Imperial Japanese Navy

Air Raid on Yokosuka, 18 July 1945

By July 1945, what was left of the Imperial Japanese Navy was immobilized in Japanese ports due to lack of fuel and critical maintenance. Japanese ships contributed to the anti-aircraft defenses of several major bases, several of which, especially the main naval base at Kure, were already heavily defended by shore-based anti-aircraft weapons, making air attacks on the bases a formidable prospect. Although some argued that attacking the ships was unnecessary as the Japanese navy was a spent force, Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz wanted them destroyed, and Admiral William Halsey carried out his orders.

Following strikes by Task Force 38 carrier aircraft in the Tokyo area on 10 July, photo-reconnaissance analysis revealed Japanese battleship Nagato deep in a cove at Yokosuka. Nagato was the flagship of the commander-in-chief of the Japanese Combined Fleet, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, at the time of the attack on Pearl Harbor. (There is a meticulously accurate full-scale replica of Nagato in the opening scene of the 1970 Pearl Harbor movie Tora! Tora! Tora! The super-battleship Yamato was commissioned on 16 December 1941 and Yamamoto shifted his flag to her in February 1942.) By the spring of 1945, Nagato had been relegated to a floating coastal defense battery to defend against landings in Sagami Wan and Tokyo Bay. Most of her anti-aircraft weapons were removed and placed on high hills around the ship. Her secondary battery was also removed and dispersed to be used in an anti-landing role at Yokosuka. Moreover, she was anchored in water that was too shallow for torpedoes. In addition, she was heavily camouflaged with netting to include potted pine trees and other plants.

Commencing about 1540 on 18 July, about 100 SB2C Helldiver dive-bombers from carriers Essex (CV-9), Yorktown (CV-10), Randolph (CV-15) and Shangri-La (CV-38) attacked the NAGATO, followed by F6F Hellcats from Belleau Wood (CVL-24). In order to maximize underwater hull damage, the dive-bombers had orders to aim for near misses. The raid was originally scheduled for 0400, but was delayed due to bad weather. Three waves of 592 aircraft struck Yokosuka and other targets toward Tokyo, led by 62 TBM Avengers, each armed with four 500-pound bombs, which attacked the 154 heavy anti-aircraft guns and 225 machine guns around Yokosuka harbor.

At 1540, 60 Helldivers dove on Nagato, led by planes from Yorktown and Randolph. At 1552, Nagato took a direct hit by a 500-pound bomb, which killed her commanding officer, Rear Admiral Miki Otsuka, along with the executive officer, the radar officer, and 12 other sailors. An ensign briefly assumed command until a severely burned commander (the main battery gunnery officer) took charge. Shortly afterward, another bomb hit the aft shelter deck and exploded at the base of the No. 3 16-inch gun turret, killing about 25 men and destroying four 25-mm anti-aircraft gun mounts. Later, a 5-inch rocket hit the fantail (some accounts say it was an 11.75-inch “Tiny Tim” rocket). It was a dud and passed out the starboard side. The converted minesweeper Harashima Maru was alongside Nagato and was blown in two. Despite the intensity of the attack with 270 tons of bombs, Nagato remained afloat. She would finally capsize and sink on 29 July 1946 only after being severely damaged by the second atomic bomb test at Bikini Atoll on 24 July (the first test on 1 July only caused moderate damage).

The attack on Yokusuka ended at about 1610. The old (a 1905 Battle of Tsushima veteran) armored cruiser Kasuga, the incomplete small destroyer Yaezakura, and submarine I-372 were sunk. The pre-dreadnaught battleship Fuji (also a Tsushima veteran, used as a training vessel) and the obsolete destroyer Yakaze (used as a target-control vessel) were damaged. U.S. losses in the attack were 14 aircraft and 18 aircrewmen, most lost in the intense anti-aircraft fire at Yokosuka. Although the results of the raid were a disappointment, what was not known at the time was that the bomb that destroyed Nagato’s bridge hit the spot where Admiral Yamamoto had given the order to attack Pearl Harbor.

Raids on Kure and the Inland Sea, 24–28 July 1945

The Fast Carrier Task Force (TF 38) and other elements of the Third Fleet had been operating continuously at sea since early July, conducting multiple strikes on the Japanese home islands (some of these are covered in H-Gram 051), interspersed with massive replenishment-at-sea operations, and dodging several typhoons. On 21–22 July, Third Fleet conducted what is probably the largest single replenishment-at-sea operation in history. Over 100 ships received 6,369 tons of ammunition, 379,157 barrels of fuel oil, 1,635 tons of stores and provisions, 99 replacement aircraft, and 412 replacement personnel from the oilers, ammunition ships, stores ships, and escort carriers of Task Group 30.8, commanded by Rear Admiral Donald B. Beary, an unsung hero of World War II (he received two Legion of Merits for executing the extraordinary logistics effort for the Third and Fifth Fleets from October 1944 to the end of the war).

The commander of the Third Fleet, Admiral William F. Halsey, Jr., received orders from Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz to destroy the remnants of the Imperial Japanese Navy, most of which were at the heavily defended naval base at Kure, on Japan’s Inland Sea (the body of water between Honshu, Shikoku, and Kyushu that had served as a sanctuary from U.S. submarine attacks). The commander of TF-38, Vice Admiral John “Slew” McCain, Sr., argued against the mission, and most of his staff strongly opposed it. Kure had been hit previously on 19 March during Fifth Fleet Commander Admiral Raymond Spruance’s third series of attacks on the Japanese home islands. About 240 aircraft from Vice Admiral Marc “Pete” Mitscher’s Task Force 58 carriers attacked Japanese ships in Kure, while others attacked targets around the Inland Sea. Although most of the Japanese ships in Kure on that day had been hit, none had been sunk, and 11 F6F Hellcat fighters and two TBM Avenger torpedo bombers had been lost in the heavy flak. Worse, the relatively small Japanese air counter-attack had inflicted grievous damage to carrier Franklin (CV-13) and severe damage to Wasp (CV-18). Wasp only returned to the fight on 25 July 1945 and Franklin never would. The 19th of March had cost almost 1,000 U.S. sailors and airmen their lives (see H-Gram 043). Nevertheless, Halsey had his orders.

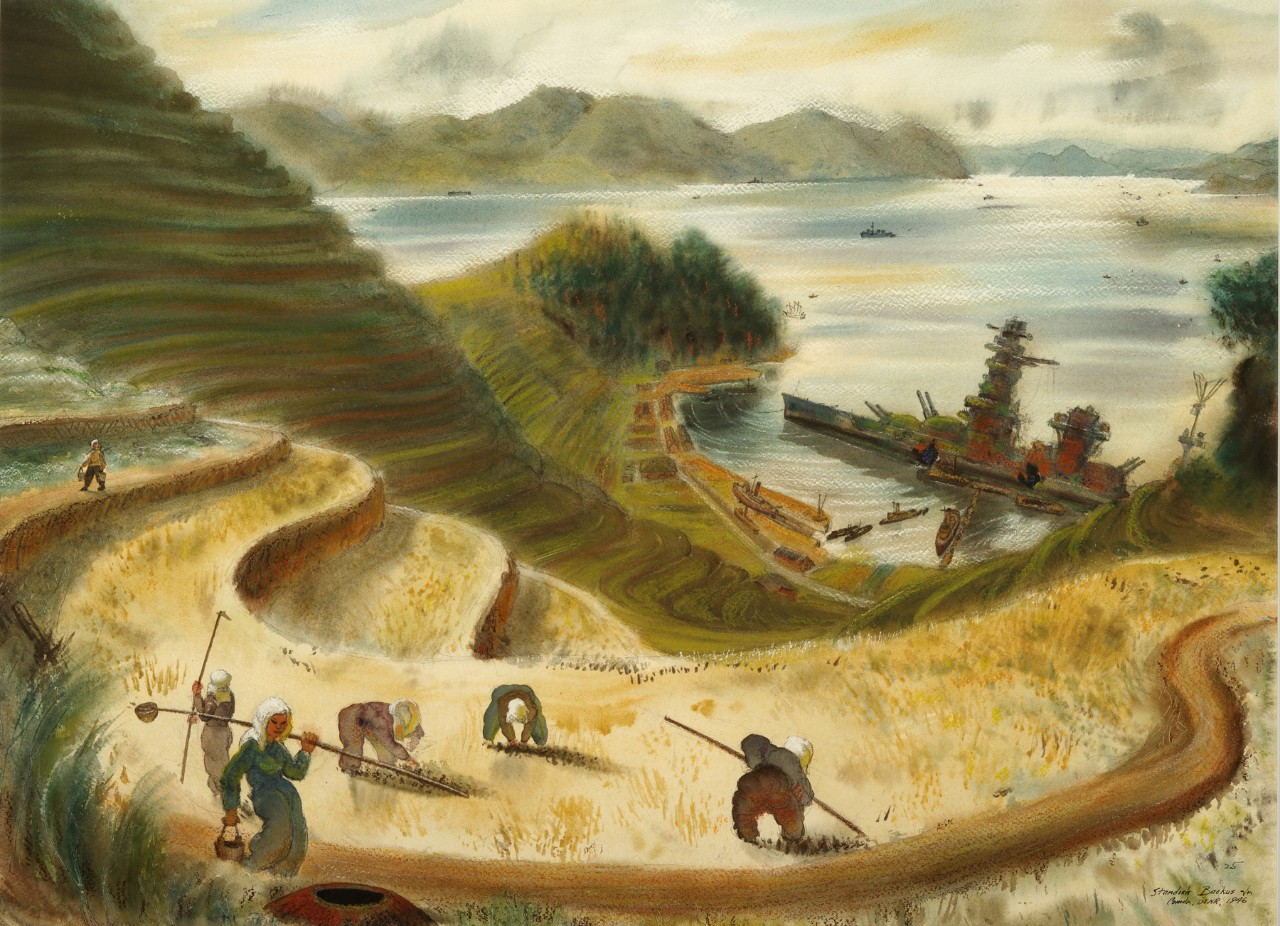

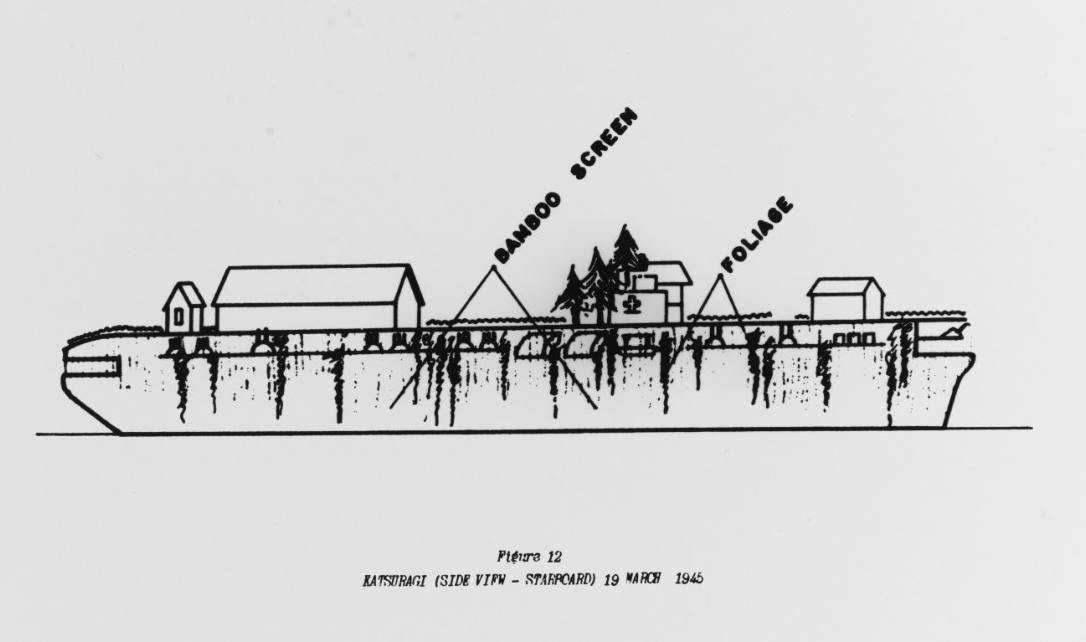

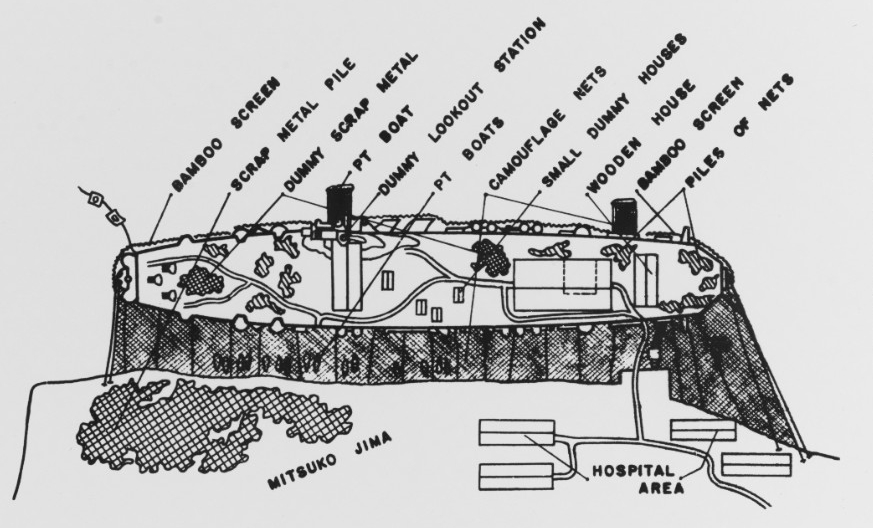

In the meantime, the Japanese went to great lengths to protect the remaining ships at Kure, which included two new aircraft carriers (without aircraft), three smaller carriers, three battleships, two heavy cruisers,, and other ships, all of which were essentially immobilized due to lack of fuel. The ships were widely scattered about the harbor, tucked right against steep hills on the shoreline in shallow water, and heavily camouflaged—to the point where the carriers had fake buildings, potted trees, and even sand “roads” on their flight decks in addition to deceptive paint jobs and extensive netting—each protected by nearby anti-aircraft artillery on the hills. All of this made the ships very difficult targets to find and to hit, and even if the ships sank, they weren’t going very far down in 25 feet of water.

Due to the shallow water in Kure Harbor as well as the extensive triple-A ringing the harbor, the U.S. Navy planners ruled out using torpedoes as both impractical and too deadly to the torpedo bombers. However, the TBM Avengers did employ a new weapon for this operation: radar-fuzed airburst bombs that proved far more effective at taking out anti-aircraft guns than trying to hit a dug-in gun emplacement with a conventional bomb. Although the guns themselves could often survive an airburst, their crews didn’t. Another weapon used by a few Avengers on this strike was the rarely employed 2,000-pound general-purpose bomb, of which the carriers only embarked a handful.

As TF-38 steamed south to get in launch position for the strike on Kure, Destroyer Squadron 61, commanded by Captain T. H. Hederman, was detached to conduct an anti-shipping sweep through Sagami Wan (south of Tokyo) on the night of 22–23 July. Shortly after midnight, DESRON 61 detected four radar contacts and opened fire with guns and torpedoes, sinking the 800-ton cargo ship No. 5 Hakutetsu Maru and damaging the 6,919-ton freighter Enbun Maru. The minesweeper W-1, sub chaser CH-42, and shore batteries mounted a spirited but ineffective defense and no U.S. ships were hit as they exited the area. This was the last surface engagement of the war (not counting those conducted by the Soviets).

On the morning of 24 July, Task Force 38 included 15 fast carriers (nine Essex-class and six Independence-class light carriers) with over 1,200 aircraft. This would grow with the arrival of Wasp from repair the next day. It was also augmented by the four British carriers of Task Force 37. TF-38 was escorted by eight fast battleships, 15 cruisers, and 61 destroyers. The British force also included a battleship, six cruisers, and 18 destroyers. Because the strike on Kure was intended by Nimitz to be a final revenge for Pearl Harbor, the British force was specifically excluded and given targets in the Osaka area instead. In short, the U.S. Navy didn’t want to share credit with anyone else (the Royal Navy or the U.S. Army Air Forces) for the final destruction of the Japanese navy. Of note, of the U.S. carriers, none had even been launched at the time of the Pearl Harbor attack, although all the Essex-class units had been authorized and ordered in 1940 and 1941 before the attack.

TF-38 was divided into three task groups:

- TG 38.1 (Rear Admiral Thomas L. Sprague) included Lexington (CV-16), Hancock (CV-19), Bennington (CV-20), Belleau Wood (CVL-24), and San Jacinto (CVL-30)

- TG 38.3 (Rear Admiral Gerald F. Bogan) included Essex (CV-9), Ticonderoga (CV-14), Randolph (CV-15), Wasp (CV-18), Monterey (CVL-26), and Bataan (CVL-29)

- TG 38.4 (Rear Admiral Arthur W. Radford) included Yorktown (CV-10), Shangri-La (CV-38), Bon Homme Richard (CV-31), Independence (CVL-22), and Cowpens (CVL-25) (

Shangri-La and Bon Homme Richard were new arrivals. Almost all the other carriers had been knocked out of action at some point by kamikaze and had been repaired and returned to the fight.

TF-38 Carrier Strikes, 24 July

At 0440 on 24 July 1945, TF-38 commenced launching the first of 1,363 sorties to strike Kure Naval Base and numerous other targets around the Inland Sea. The Japanese continued to withhold the vast majority of their aircraft, waiting for the main invasion, and steadfastly maintained that discipline throughout. The initial fighter sweeps by Hellcats and Corsairs encountered little opposition, but claimed shooting down 18 Japanese aircraft in the air, destroying another 40 on the ground, and damaging 80 on the ground. During the day, TF-38 aircraft dropped 599 tons of bombs and fired 1,615 rockets. Although the ships in Kure were the primary target, with little air opposition, U.S. fighters went on a rampage around the Inland Sea, shooting up anything of value in sight, including 16 locomotives, three oil tanks at Kure and another at Tano, damaging barracks, warehouses, power plants, factories, and about 20 hangars. In Kure itself, 22 warships totaling 258,000 tons were sunk or badly damaged. An additional 53 vessels totaling about 17,000 tons were sunk in various harbors and bays around the Inland Sea.

The new carrier Amagi (commissioned August 1944) had never been operational due to lack of trained carrier pilots, and only had a skeleton crew on board, but was a main focus of the attacks on 24 July. She was the second of six fleet carriers of a modified Hiryu design (about 17,500 tons, capable of embarking about 57 aircraft) that the Japanese tried to build during the war. The lead ship, Unryu had been completed, but was sunk on 19 December 1944 by submarine Redfish (SS-395) while being used as an aircraft ferry and ammunition transport. Amagi and Katsuragi were completed, but never embarked their own air groups. Kasagi, Aso, and a somewhat larger design, Ikoma, were never completed as construction was suspended due to lack of material.

Amagi had suffered some damage during the 19 March raid. On 24 July, she was attacked by 30 carrier aircraft in the morning and another 20 in the afternoon, and suffered numerous near misses that caused her to start to list even before she was hit by a 2,000-pound bomb at 1000. This caused a huge explosion and massive destruction. The big bomb was delivered by an Avenger from either Bennington or Hancock. As the flooding continued, the skipper ordered the ship abandoned, over the objection of the engineers. The abandon-ship order was considered pre-mature (and the skipper subsequently relieved of command) as counter-flooding corrected Amagi’s list and at the end of the attack she was still afloat.

The new carrier Katsuragi had been slightly damaged in the 19 March raid and got off lightly again on 24 July as her extensive camouflage appeared to work well and Amagi attracted most of the attacks. Katsuragi was attacked by 10–12 aircraft and hit by one 500-pound bomb that destroyed a gun sponson and killed the gun’s entire 13-man crew, but otherwise inflicted little structural damage.

Light carrier Ryuho (capable of 30 aircraft) had survived the Battle of the Philippine Sea, but had been badly damaged by three bombs and two rockets during the 19 March raid and had not been repaired. However, her camouflage was so good on 24 July—and good discipline kept her crew from anti-aircraft fire that would have given her away—that she was not attacked by any U.S. aircraft.

The old carrier Hosho (Japan’s first aircraft carrier, and the first ship in the world designed to be, and completed as a carrier) was hit by one bomb and slightly damaged on 24 July. She would survive the war.

The escort carrier Kaiyo had been badly damaged by near misses on 19 March. She was discovered by U.S. fighters on 24 July and attacked with rockets, but probably not seriously damaged. However, as she was trying to reach another port, she struck a U.S.-laid magnetic mine that caused severe damage and flooding aft. She was under tow by destroyer Yukaze when she was attacked by Hellcat fighters and hit with two rockets. She was then deliberated grounded to prevent sinking.

Following the loss of four carriers at the Battle of Midway, the Japanese battleships Ise and Hyuga had been converted in 1943 into “hybrid” battleship-carriers by replacing the aft two twin 14-inch gun turrets with a hangar and flight deck (they retained the two 14-inch gun turrets forward and the two amidships). They could carry about 22–24 aircraft, with the intent for half to be Judy dive-bombers (which would have to land on a conventional carrier or on land) and half floatplane fighters that could be recovered. Although they had carried no aircraft, the two battleship-carriers were part of the Japanese decoy carrier force during the Battle of Leyte Gulf in October 1944, and although all four of the Japanese carriers were lost, Ise and Hyuga survived. They both also survived the 19 March raid on Kure (Ise with two bomb hits and Hyuga with three bomb hits), but their luck ran out in July.

Commencing at 0615, Ise was attacked by 30 aircraft, suffering four direct hits and numerous nearmisses. At noon, another 30 planes attacked and Ise took a direct hit on the bridge that killed her skipper, Captain Mutaguchi. Over 50 of her crew were killed and she began to settle by the bow. Although the bow was on the bottom, she was technically still afloat when the raid ended.

Over 50 aircraft attacked battleship Hyuga with 200 bombs during the course of the day with 10 direct hits and about 30 damaging near misses that opened seams, causing flooding. During the fifth attack, three bombs hit near the bridge in quick succession, killing her skipper, Rear Admiral Kiyoshi Kusakawa (Japanese battleship captains had been given promotions to rear admiral to buck up morale). Hyuga began to settle by the stern with over 200 dead and 600 wounded. The battleship finally came to rest on the shallow bottom on 26 July.

Battleship Haruna was the last survivor of a class of four ships originally built as battle-cruisers during World War I, and due to their speed were frequent escorts of the Japanese carrier force. Her sisters Hiei and Kirishima had been lost in surface actions at Guadalcanal in November 1942, and Kongo had been sunk in the Formosa Strait by submarine Sealion (SS-315) on 21 November 1944. Haruna had survived the battles of Midway, Santa Cruz, Philippine Sea, and Leyte Gulf, and she had shelled U.S. Marines on Guadalcanal. She had taken one bomb hit with light damage during the 19 March raid. Her luck continued on 24 July as she was only attacked by about 10 planes and suffered a gash above waterline from a bomb hit aft. (This gash, however, would ultimately prove fatal.)

The heavy cruiser Tone was a veteran of the Pearl Harbor attack (her floatplane verified that the U.S. Pacific Fleet was not at the Lahaina anchorage off Maui an hour before the attack) and had survived the battles of Eastern Solomons, Santa Cruz, Philippine Sea, Leyte Gulf, and numerous lesser engagements. She’d taken one bomb hit during the 19 March raid that jammed her No. 3 8-inch turret. On 24 July, she was attacked by about 100 aircraft during the day, suffering four direct hits and seven near misses. Leaking badly, she was deliberately beached.

Like Tone, the heavy cruiser Aoba was a veteran of numerous battles including Coral Sea, Savo Island. and Cape Esperance. She escaped damage during the 19 March raid, but on 24 July she was attacked by 30 carrier aircraft with one direct hit and a near miss that caused significant damage below the waterline. Attempts to counter-flood were only partially successful, and Aoba settled to the shallow bottom with a starboard list.

The relatively new light cruiser Oyodo (commissioned February 1943) was the flagship for the commander-in-chief of the Combined Fleet before the headquarters moved ashore in September 1944. She then served as the flagship of Vice Admiral Jisaburo Ozawa, in command of the Japanese decoy carrier force during the Battle of Leyte Gulf. During the raid on Kure in 19 March, she’d taken serious damage from three bomb hits and had been beached to prevent sinking, with a loss of 52 of her crew. Subsequently repaired, on 24 July she was attacked by about 50 carrier aircraft and was hit by five bombs, one of which started a fire that took two days to extinguish. But, at the end of the day, she was still afloat and fighting back.

The elderly (1921-vintage) light cruiser Kitakami had been modified in late 1944 to carry eight Kaiten manned suicide torpedoes, but never operated with them. On 24 July, she was damaged by strafing and near misses, with 32 of her crew killed.

The 1909-vintage Dreadnaught-type battleship Settsu (which by 1940 was used as a radio- controlled target ship), was attacked by 30 Hellcat fighters near the Japanese naval academy at Etajima. She was struck by three bombs and many near misses, and was deliberately run aground. She settled to the shallow bottom on 26 July.

What might have been the oldest warship sunk in World War II, three near misses on the armored cruiser Iwate (commissioned 1901) opened her seams and she sank.

Other ships sunk or severely damaged in the attack on Kure included one large oiler and two destroyers. In addition to the ships at Kure, U.S. aircraft hit and damaged the aircraft carrier Aso, under construction (60 percent complete) at Kobe.

British Task Force 37 flew 257 sorties in the Osaka area on 24 July, claiming to damage some destroyers and destroyer escorts. The British strikes did discover the heavily camouflaged escort carrier Shimane Maru hidden in Shido Bay. Shimane Maru was a relatively new escort carrier, converted from an oiler, which had never been operational, and had been badly damaged in the 19 March raid on Kure. This time, she was hit by aircraft from HMS Victorious, broke in two, and sank. Although not much of a carrier, this was technically the only carrier vs. carrier action in Royal Navy history. (A case could be made that the first was when Japanese carriers sank HMS Hermes in the Indian Ocean on 9 April 1942, although Hermes’ aircraft had been disembarked. Shimane Maru, however, was equally as defenseless.)

During the night of 24–24 July, TF 38 aircraft flew a number of night harassment air raids (Bon Homme Richard was equipped and trained as a “night carrier.”) In addition, Task Group 35.3, commanded by Rear Admiral Cary Jones, which included the light cruisers Wilkes-Barre (CL-103), Pasadena (CL-65), Springfield (CL-66), and Astoria (CL-90) along with six destroyers, bombarded the Kushimoto seaplane base at Cape Shionomisaki, inflicting moderate damage.

TF-38 Carrier Strikes, 25 July

On the morning of 25 July, TF-38 commenced launching additional strikes around the Inland Sea, expanded to include the Nagoya-Osaka area. The carriers launched 655 sorties before increasingly foul weather truncated the operation at 1300. Nevertheless, TF-38 aircraft dropped 185 tons of bombs and fired 1,162 rockets, sinking nine merchant ships of about 8,000 tons total, and damaging a destroyer and about 35 other vessels. Eighteen Japanese planes were shot down, with 61 more claimed destroyed on the ground and another 68 claimed damaged. Ground targets hit included locomotives, gasoline trucks, 20 hangars, tunnels, and other railroad infrastructure.

TF-38 Carrier Strikes, 28 July

On 28 July, TF-38 and TF-37 launched another massive series of strikes at targets around the Inland Sea. The primary target was once again Kure Naval Base to finish off the Japanese warships, and in some cases bomb them deeper into the mud. Commencing at 0443, TF-38 launched 1,602 sorties that expended 605 tons of bombs and 2,050 rockets. In what appeared to be a completely uncoordinated action, U.S. Army Seventh Air Force B-24 four-engine bombers flying from Yontan airfield on Okinawa flew a series of raids throughout the day targeting Japanese navy ships in Kure, but hitting only one already sunken ship. The B-24s did draw considerable flak; two were shot down and eight damaged.

The already badly damaged carrier AMAGI was attacked by 50 carrier aircraft in the morning and another 30 in the afternoon, with one direct hit and numerous near misses. (B-24 bombers also bombed her around 1200, with no hits.) By 1000 on 29 July, Amagi had settled to the bottom in shallow water with a 70-degree list. Although she was mostly still above water, Amagi was technically the last Japanese carrier sunk in World War II.

The carrier Katsuragi, lightly damaged on 24 July, was attacked by 10–15 aircraft, taking two direct hits including a devastating one from a 2,000-pound bomb just aft of the island, which caused massive damage and killed the executive officer and most of those on the bridge. Despite the extensive damage topside, damage below the waterline was minimal and the ship remained afloat, and was still afloat at the end of the war.

The non-operational light carrier Ryujo once again escaped being attacked due to her good camouflage. The old carrier Hosho was not hit, either.

The already-grounded escort carrier Kaiyo was attacked by 16 VBF-83 Corsairs from Essex with 54 rockets. Eighteen hits were claimed; probably only three hit, but Kaiyo came to rest on the bottom in shallow water. Although technically sunk, she would be attacked by 12 U.S. Army Airforces B-25 twin-engine bombers on 9 August. The wingtip of the lead B-25 hit Kaiyo’s camouflage netting and the aircraft crashed into the water.

Sixty aircraft attacked the battleship-carrier Ise, scoring six direct hits and nine damaging near misses. At 1100, Helldivers from Hancock hit Ise with four more bombs, followed by Hancock Corsairs carrying bigger 1,000-pound bombs and hitting with five of them. The tough battleship finally settled to the bottom with her main deck awash. At 1400, 24 B-24s bombed the sunken ship, but all missed.

Although already on the bottom, battleship-carrier Hyuga still took many hits and was finally abandoned. She was also bombed by 24 B-24s with no hits.

Battleship Haruna’s luck finally ran out. She was attacked nearly continuously throughout the day by dozens of aircraft, which accumulated 13 direct hits and 10 damaging near misses. As she took on a list, the gash from the hit from the 24 July raid was submerged and tons of water flooded into the ship. She finally settled to the bottom in shallow water, with 65 of her crew dead. B-24s attacked her, too, with no hits.

The already-beached heavy cruiser Tone was attacked yet again by numerous carrier aircraft, suffering two more direct hits and seven near misses. She took on a 21-degree port list and despite counter-flooding settled to the shallow bottom. (Although the Imperial Japanese Navy generally behaved with more respect for the rules of armed conflict than the Japanese army, Tone was the site of a notable exception, when on 18 March 1944, 72 seamen captured from the British freighter SS Behar were beheaded. Rear Admiral Sakonjo, who ordered the executions, was hanged by the British as a war criminal after the war.)

Although already on the bottom, heavy cruiser Aoba was attacked again by 10 carrier aircraft in the morning and 10 more in the afternoon with a cumulative four direct hits, which set the ship on fire. At 1600 in the afternoon, after a day of utter futility, the Army Air Forces’ B-24 bombers finally hit something: Four bombs hit the sunken Aoba, blowing off her stern.

Light cruiser Oyodo was attacked by 40 dive-bombers and fighters, taking four more direct hits and numerous near misses that ruptured hull plating. She began to list. After several hits near the bridge, the commanding officer ordered counter-flooding, which failed to correct the list. Abandon ship was ordered, but too late. At about 1200, the ship rolled over on her side. About 223 of her crew were killed in the attack or trapped when she ended up on her side in shallow water. Another 180 crewmen were wounded. At some point later, U.S. fighters fired rockets into her exposed underside.

With more bomb-carrying aircraft than remaining targets, U.S. carrier aircraft attacked Battle of Tsushima veteran armored cruiser Izumo, moored at the Japanese Etajima naval academy. Three near misses caused the ship to capsize.

The new destroyer Nashi (completed 15 March 1945) was also sunk near Kure by TF-38 aircraft with one direct bomb hit and a near miss. British aircraft sank two frigates, CD No. 4 and CD No. 30.

Task Force 38 fighters attacked 30 Japanese airfields in conjunction with the Kure raid on 28 July, claiming 115 Japanese destroyed on the ground and 21 in the air. Other targets struck and destroyed included 14 locomotives, four oil cars, two railroad roundhouses, three oil tanks, three warehouses, one hangar, and a transformer station. Other targets damaged included eight locomotives, 13 hangars, 8 factories, two copper smelters, two lighthouses, one railroad station, multiple roundhouses, numerous oil tanks, two radio stations, various barracks, and the Kawasaki aircraft factory.

If nothing else, the Kure raids were a case study in how hard it is to hit even a stationary ship with bombs, and how hard it was to sink a ship using only bombs, although the fact that Japanese ships were built extremely tough was a significant factor as well. The heavy flak that disrupted aim didn’t help either.

In the four-day operation, TF-38 flew 3,620 offensive sorties (plus 672 British sorties from TF-37). U.S. aircraft dropped 1,389 tons of bombs, fired 4,827 rockets, and claimed 52 Japanese aircraft shot down and another 216 on ground. There were 170 Navy Crosses awarded, five of them posthumously. The cost was high: 101 U.S. Navy aircraft were downed and 88 men killed.

By the end of the strikes on Kure, the Imperial Japanese Navy had been virtually annihilated. Of 25 Japanese aircraft carriers and escort carriers, only five were still afloat, all damaged. Of 12 battleships, only Nagato was still afloat. Of 18 heavy cruisers, only two, badly damaged, remained at Singapore. Of 22 light cruisers, only two survived. Of 177 destroyers, only five remained. The Imperial Japanese Navy lost 334 warships (out of 611 total vessels) and just over 300,000 men during the course of the war. Over 2,000 Japanese merchant ships were sunk with tens of thousands of crewmen lost.

Countering Operation Tsurugi, 9–10 August

In August 1945, U.S. intelligence got wind of a Japanese navy plan to launch a long-range airborne suicide commando attack on the U.S. B-29 bases in the Marianas. Code-named Operation Tsurugi (“Sword”), the plan went through several iterations, but in its final form called for 30 navy P1Y Frances twin-engine bombers and 60 G4M Betty bombers to carry 300 commandos of the 101st Kure Special Naval Landing Force and 300 commandos of the army’s 1st Raiding Regiment to the Marianas, with a target date of 19 August 1945. Twenty G4Ms would take Navy commandos to Guam. Twenty G4M’s would take army commandos to Saipan. Another 20 G4Ms would take army and navy commandos to Tinian. The P1Ys would strafe the airfields before the specially modified G4Ms belly-landed on the airfields and disgorged their troops to do as much damage as possible on what was intended to be a one-way suicide mission. There was also a plan to seize an intact B-29 and fly it back to Japan (which almost certainly wouldn’t have worked).

With advanced warning, Fleet Admiral Nimitz ordered Admiral Halsey to take the Third Fleet north and attack the staging airfields for the operation near Misawa in northern Honshu and on Hokkaido. On 9 August, as the Soviets invaded Japanese-occupied Manchuria and southern Sakhalin Island, a large strike from Task Force 38 carriers came in at treetop level (the better to see dispersed planes in heavy camouflage). TF-38 launched 1,212 offensive sorties. The carrier planes claimed 251 aircraft destroyed on the ground and 141 damaged. At least 20 of the P1Y’s and 29 G4M’s earmarked for Operation Tsurugi were among those destroyed. On 10 August, TF-38 planes attacked again, launching 1,364 sorties and hitting two previously unlocated airfields, among other targets. British Task Force 37 also contributed. Despite the damage and disruption, the Japanese did not actually cancel the operation, but it was rendered moot when the emperor announced a cease-fire on 15 August. The U.S. Navy lost 34 aircraft and 19 airmen during the strikes, while the British lost 13 aircraft and nine airmen. A Royal Canadian Navy pilot flying an F-4U Corsair from HMS Formidable was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross for sinking the Japanese destroyer-escort Amakusa. (Japanese sources indicate his damaged plane crashed into the bay, but the award citation says he crashed into the Amakusa after hitting it with a 500-pound bomb.)

Battleships and heavy cruisers steam in column off Kamaishi, at the time they bombarded the iron works there, as seen from USS South Dakota (BB-57). USS Indiana (BB-58) is the nearest ship, followed by USS Massachusetts (BB-59). Cruisers Chicago (CA-136) and Quincy (CA-71) bring up the rear (80-G-490143).

Shore Bombardments of Japan, July–August 1945

Following the fall of Okinawa to U.S. forces in late June 1945, the Japanese ceased massed kamikaze attacks, although small numbers would occasionally try to achieve surprise (see H-Gram 051). In fact, they ceased most air operations of any kind (including fighter defenses against B-29 bombers) in order to conserve aircraft for the final defense of Japan. Most aircraft were dispersed away from airfields and carefully camouflaged. The comparative lack of Japanese air activity emboldened the commander of the Third Fleet, Admiral William F. Halsey, Jr., to commence a series of battleship shore bombardments against coastal Japanese industrial targets, at first cautiously, and then with increasing audacity. Part of the rationale for the bombardments was to draw out Japanese aircraft so they could be shot down, but the Japanese steadfastly refused to take the bait.

Kamaishi, Northern Honshu, 14 July

In broad daylight, at 1210 on 14 July, three fast battleships, two heavy cruisers, and nine destroyers of Task Unit 34.8.1 (Bombardment Group Able) opened fire on the Kamaishi works of the Japan Iron Company on the east coast of northern Honshu. Commanded by Rear Admiral John Shafroth, the force included the battleships South Dakota (BB-57), Indiana (BB-58), and Massachusetts (BB-59), and heavy cruisers Quincy (CA-71) and Chicago (CA-136). Shafroth had temporarily relieved Vice Admiral Willis “Ching” Lee (the Navy’s foremost expert on radar-directed gunfire). Lee had been recalled by Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King to set up Experimental Task Force 69 (ETF-69) at Casco Bay, Maine, to develop improved tactics to defeat Japanese kamikaze. Lee, however, died of a heart attack on 25 August, before returning to the Far East.

The bombardment of Kamaishi was preceded by months of meticulous planning and was covered by a special combat air patrol of 20 fighters from carrier Task Group 38.1. At 1055, the flagship South Dakota hoisted a signal that read, “Never forget Pearl Harbor.” Haze limited visibility to 14,000–20,000 yards. Thus, the ships fired based on radar at a range of 26,000 yards because of the need to remain clear of potentially mined waters inside the 600-foot depth curve. The Japanese were essentially caught by surprise, and ineffective anti-aircraft fire was directed against the CAP. During the battleship bombardment, three large merchant ships and a small escort ship sortied from the inner bay and somewhat miraculously sailed through a storm of gunfire from U.S. destroyers without being hit before escaping. One Corsair fighter was shot down strafing a destroyer-escort.

The U.S. ships ceased fire at 1419 after expending 802 16-inch, 728 8-inch, and 825 5-inch shells. Most of the shells landed in the target area with direct hits noted on open hearths, coke ovens, foundries, a rolling mill, and other steel mill infrastructure. An oil tanker, a small ship, and two barges in the harbor were also sunk. The damage and destruction was actually even worse than it appeared, setting back production by about two months (i.e., for the rest of the war). Concussions from the explosions overturned cooking stoves and caused numerous fires to break out in the city, which Japanese propaganda played up. Nevertheless, and despite the propaganda, the psychological effect was profound. Post-war analysis indicated that the battleship bombardment instilled far more fear in the Japanese population than high-explosive or incendiary bomb attacks. The bombers came from far away, but the ships were right on the doorstep in sight, and no amount of propaganda could cover that up.

Muroran, Southern Hokkaido, 15 July

On the night of 14–15 July, Task Unit 34.8.2 (Bombardment Group Baker), under the command of Rear Admiral Oscar C. Badger, detached from the carrier task force to make a run for Muroran, Hokkaido. The audacious approach would require a three-hour run with land on three sides, going in and going out. At 0936 on 15 July, fast battleships Iowa (BB-61), Missouri (BB-63), and Wisconsin (BB-64), light cruisers Atlanta (CL-104) and Dayton (CL-105), and eight destroyers opened fire on the Nihon Steel Company and the Wanishi Ironworks, Japan’s second largest producer of coke and pig iron. Badger’s flagship Iowa hit the Nihon furnaces on the second salvo and Missouri’s gunfire resulted in a massive explosion (much to Halsey’s satisfaction, as Missouri was his flagship). Wisconsin’s ninth salvo also caused a “terrific explosion.”

At 1025, the U.S. force ceased fire after expending 860 16-inch shells, of which 170 were direct hits. The damage to the plants at Muroran was even more severe than at Kamaishi. Over 2,500 houses in Muroran were destroyed by secondary fires caused by concussion. Again, the psychological impact was perhaps even more severe than the physical, as Halsey later stated that the bombardments showed the Japanese that “we made no bones about playing in his front yard.” The Japanese war minister was forced to formally apologize for the inability to do anything about Third Fleet’s attacks.

Hitachi, East Coast of Honshu, 17–18 July

Emboldened by the first two bombardments and the virtual lack of Japanese opposition, Admiral Halsey ordered yet another shore bombardment, this time on the coast of Honshu only 80 nautical miles from Tokyo, albeit at night. Again commanded by Rear admiral Badger, this time Bombardment Group Baker included battleships Iowa, Missouri (with Halsey embarked), Wisconsin, North Carolina (BB-55), and Alabama (BB-60), and light cruisers Atlanta and Dayton, and eight destroyers. Badger’s force was joined by the British battleship King George V (with Vice Admiral Sir Bernard Rawlings, RN, Commander Task Force 37 embarked), and two British destroyers. The targets were in Hitachi, a major electronics production center. The force opened fire at 2314 on 17 July and delivered 1,206 16-inch shells plus 267 14-inch shells from the British battleship, badly damaging several plants and installations, and virtually wiping out the copper production capability of the Hitachi mine. From this point on, Third Fleet ships shelled Japanese targets almost every day that weather and refueling requirements permitted.

Of note, night air cover was provided by aircraft from Night Carrier Air Group NINE ONE (CVG(N)-91) embarked on newly arrived carrier Bon Homme Richard. Bon Homme Richard was the last Essex-class carrier to be completed in time to see combat in World War II. The “Bonnie Dick” was designated the “night carrier” after Enterprise (CV-6) was knocked out of action by a kamikaze, hence the CV(N) designation (which doesn’t mean “nuclear”). CVG(N)-91 was specially equipped and trained for night operations. She would be the only carrier to serve as an “attack” carrier in three wars: World War II, Korea, and Vietnam. Combining her Korean and Vietnam record, her aircraft shot down more MiG jet fighters than any other carrier. Her official name is also misspelled: The name of John Paul Jones’s ship was Bonhomme Richard (which was correctly applied to LHD-6).

Cape Nojima, 18–19 July

A less-successful bombardment occurred the night of 18–19 July, when Task Group 35.4, commanded by Rear Admiral Carl Holden, swept Sagami Wan (off Kamakura). After finding no shipping, the light cruisers Topeka (CL-67), Duluth (CL-87), Oklahoma City (CL-91), Atlanta, and five destroyers bombarded the Cape Nojima radar site (near the entrance to Tokyo Bay). The cruisers fired 240 6-inch rounds, which all fell short, blowing up rice paddies and a village.

Hamamatsu, 29–30 July

On the night of 29–30 July, Rear Admiral Shafroth’s Bombardment Group Able made a high-speed run to Hamamatsu (on the east coast of Honshu near Nagoya). The force included battleships South Dakota, Massachusetts, Indiana, and HMS King George V, heavy cruisers Quincy, Boston (CA-69), Saint Paul (CA-73), and Chicago, and 10 U.S. and three British destroyers. Bon Homme Richard’s night air group provided night gunfire spotting. The force made two bombardment runs from 2315 to 0027, inflicting damage on an Imperial Government Railway locomotive factory and destroying other critical railway infrastructure. This would be the last time a British battleship ever fired main battery guns in battle. Although Hamamatsu had previously been hit by over 30 air raids, the battleship bombardment caused over 30,000 civilians to flee the city.

Shimizu, 30–31 July

On the night of 30–31 July, seven destroyers commanded by Captain J. W. Ludewig (Commander Destroyer Squadron 25) in John Rogers (DD-574) penetrated deep into Suruga Wan (the next major bay south of Sagami Wan), but found no shipping. The force then unleashed a very effective seven-minute bombardment (1,100 5-inch shells) at industrial facilities near Shimizu, badly damaging an oil company and an aluminum plant (118 factory buildings damaged or destroyed). The aluminum plant had already run out of raw materials and had ceased production.

Kamaishi, 9 August

On 9 August 1945, Rear Admiral Shafroth’s Bombardment Group Able struck Kamaishi for a second time. Battleships South Dakota, Indiana, and Massachusetts, heavy cruisers Quincy, Chicago, Boston, and Saint Paul, and nine destroyers were joined by British light cruiser HMS Newfoundland, New Zealand light cruiser HMNZS Gambia, and three British destroyers. British battleship King George V developed engineering problems and did not participate. Halsey later stated, “By now our contempt for Japan’s defenses was so thorough that our prime consideration in scheduling this bombardment was the convenience of the radio audience back home.” That the Japanese were deliberately holding back about 12,000 kamikaze aircraft didn’t hurt.

The 9th of August was already a momentous day. At 0001, the Soviet Union declared war on Japan and Soviet troops conducted devastatingly quick and massive attacks into Japanese-occupied Manchuria and into southern Sakhalin Island, at that point considered part of Japan proper. At 1102, the B-29 “Bockscar” dropped an atom bomb on Nagasaki, the second since the one on Hiroshima on 6 August. At 1247, the Allied ships opened fire, blasting Kamaishi essentially at will. The Japanese did put up fairly heavy anti-aircraft fire against the combat air patrol (20 fighters) and ship-launched gunfire spotting planes. Gambia took the anti-aircraft batteries under fire, while the battleships and other cruisers continued to pummel the steel plant and other infrastructure. After expending 850 16-inch shells, 1,440 8-inch shells, and 2,500 5-inch shells, there wasn’t much left. Numerous fires ignited in the city and several air raid shelters took direct hits, causing considerable civilian casualties. In addition, many Korean slave laborers were killed, along with about 42 Allied prisoners of war. The bombardment also destroyed refrigeration plants that supported Kamaishi’s large fishing industry.

The bombardment of Kamaishi is often described as the last shore bombardment of World War II. However, fighting between the Soviets and Japanese continued even after the 15 August cease-fire, until 3 September, and probably involved shore bombardments by Soviet ships during the occupation of the Kuril Islands. The heavy cruiser Saint Paul fired the last salvo of the war from a major warship. Also of note, Saint Paul had the distinction of firing the last round from sea during the Korean War, an 8-inch shell, autographed by Rear Admiral Harry Sanders, timed to hit a North Korean gun emplacement a few seconds before the armistice went into effect on 27 July 1953.

Operation Starvation: The Aerial Mine Campaign Against Japan, March–August 1945

As early as 1942, plans were being developed in the U.S. Navy for the use of U.S. Army Air Forces long-range strategic bombers for an aerial mining campaign against Japan. That year, the Navy requested that the Air Force send some personnel to attend Mine Warfare School at Yorktown, Virginia. The Air Force subsequently added minelaying to the course of study at the School of Applied Tactics in Orlando. By 1944, the staff of the commander-in-chief, U.S. Pacific Fleet, had developed detailed operations plans to mine Japanese waters using the new B-29 Superfortress bombers once airfields in the Marianas Islands in range of Japan had been secured. Admiral Chester Nimitz advocated strongly for the idea. The initial U.S. Army Air Forces response was lukewarm at best, as Air Force Chief of Staff General Henry “Hap” Arnold viewed it as a major distraction from the primary strategic bombing mission of destroying Japanese industrial infrastructure.

By a directive on 22 December 1944, General Arnold finally agreed to commit to conducting a mining campaign, but with significantly less resources than Admiral Nimitz had asked for, and with a number of conditions. The campaign would not commence until the XXI Bomber Command (the B-29s in the Marianas) reached full strength (expected in April 1945). It would only be conducted when the weather precluded attacking industrial targets ashore and would be limited to 150–200 sorties per month.

However, following the lackluster performance of the B-29s against Japanese industrial targets in the first months of 1945 using conventional high-altitude daylight “precision” bombing tactics, the new commander of the XXI Bomber Command, Major General Curtis LeMay, was in search of new and different ways to use the B-29s to achieve greater success. One of these was the switch to nighttime incendiary bombing of Japanese cities, which was more effective, but also killed hundreds of thousands of Japanese civilians. Another was the aerial mining campaign, which LeMay enthusiastically endorsed. In fact, he successfully advocated for a much greater level of effort than had originally been approved by General Arnold.

Under General LeMay’s beefed-up plan for “Operation Starvation,” the XXI Bomber Command committed an entire bomber wing (about 160 B-29s) with the intent to prevent the importation of raw material and food to Japan (Japan was not self-sufficient in either). The operation would also prevent the Japanese from supplying or reinforcing troop garrisons anywhere else and disrupt the shipping of material in Japan’s Inland Sea, which, due to Japanese mines and heavy air cover, had been immune from U.S. submarine attacks.

The 313th Bomber Wing arrived at Tinian in February 1945 and the U.S. Navy established the Tinian Mine Assembly Depot No. 4 with 12 officers and 171 enlisted men, with the purpose of training the B-29 crews and modifying the B-29s to carry the mines. Each B-29 was modified to carry either 12 Mark 26 or Mark 36 1,000-pound mines or seven Mark 25 2,000-pound mines. All these mines were parachute-retarded bottom influence mines, with magnetic fuzing, and with either pressure or acoustic sensors. All had variable sensitivity settings, randomly set arming delays, and ship counters (one to nine). The mines did not have any kind of deactivation capability and the pressure mines were considered “unsweepable” with the technology of the time (the Japanese approach to sweep them was to use suicide boats),

Phase I of Operation Starvation targeted the Shimonoseki Strait between Honshu and Kyushu (site of a little known 1863 battle between USS Wyoming and U.S,-built ships belonging to Japanese warlords in 1863, which I will cover in some future H-gram). On the night of 27 March, the commander of the 313th, Brigadier General John H. Davies, led 102 B-29s on a successful mission to mine Shimonoseki Strait, losing three aircraft with another eight damaged. By 12 April, the B-29s had sown 2,030 mines in the strait on seven missions of 246 sorties. The result exceeded expectations. Within the first month, 113 Japanese merchant ships struck mines and sank in the strait, representing 9 percent of Japan’s remaining merchant fleet.

Phase II commenced on 3 May 1945. B-29s mined the approaches to Tokyo, Nagoya, Kobe, and Osaka, and re-seeded Shimonoseki Strait. For this phase, most of the mines were the “unsweepable” 2,000-pound Mark 25 bottom influence mines. Phase III expanded the minelaying operation to the west coast of Japan and even to Korea to block shipping from the mainland of Asia to Japan. By May, the mines were sinking more ships than U.S. submarines (although this was also a function of the fact there wasn’t much Japanese shipping left that dared to sail on the high seas).

Phase IV of Operation Starvation commenced 7 June and extended and replenished already existing minefields laid in the earlier phases. Phase V was termed the “total blockade,” commencing 9 July until the end of the war, by which time the 313th had flown 1,529 sorties in 46 missions, laying 12,135 mines in 26 different minefields, for a loss of 15 B-29s and 103 aircrewmen.

About 670 Japanese ships were sunk or badly damaged (just under 500 sunk), totaling over 1.25 million tons by the mines. In the last six months of the war, the mines sank more Japanese ships than all other causes combined. The Japanese devoted almost 350 ships (many commandeered fishing trawlers) and 20,000 men to a largely unsuccessful countermine activity. The mine activity did result in an increasing scarcity of food for the Japanese population that would have led to mass starvation had the war not ended. Although the 313th Bomb Wing sorties accounted for less than 5 per cent of the XXI Bomber Command’s total sorties, the post-war Strategic Bombing Survey as well as Japanese accounts indicated that the disruption of the transport of critical raw materials actually had a greater effect on reducing Japanese war production than did the direct attacks on Japanese factories, with a bomber loss rate consistent with all XXI Bomber Command operations. In terms of damage inflicted per unit cost, the mines were the most cost-effective means to sink ships during the war. (Of note, during the war, U.S. submarines laid a total of about 650 mines.) The mines of Operation Starvation also sank a number of Japanese ships even after the war.

____________

Sources include: The Naval Siege of Japan: War Plan Orange Triumphant, by Brian Lane Herder, Osprey Publishing, 2020; Hell to Pay: Operation Downfall and the Invasion of Japan, 1945–1947, by D.H. Gianreco, Naval Institute Press, 2009; History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, Vol. XIV: Victory in the Pacific, 1945, by Samuel Eliot Morison, Little, Brown and Co.,1960; “Lessons From an Aerial Mining Campaign (Operation Starvation)” by Frederick M. Sallagar, Rand Report R-1322-PR, April 1974; The Admirals: Nimitz, Halsey, Leahy and King—The Five-Star Admirals Who Won the War at Sea, by Walter R. Borneman, Back Bay Books, 2012; The Fleet at Flood Tide: America at Total War in the Pacific, 1944–1945, by James D. Hornfischer, Bantam Books, 2016; Nimitz at Ease, by Captain Michael A. Lilly, USN (Ret.), Stairway Press, 2019; combinedfleet.com for Japanese ships; and Naval History and Heritage Command (NHHC) Dictionary of American Fighting Ships (DANFS) for U.S. ships.