H-Gram 056: The 70th Anniversary of the Korean War (Communist Chinese Offensive: November─December 1950), the 30th Anniversary of Desert Shield/Desert Storm (Part 5: December 1990), and the 75th Anniversary of the Loss of Flight 19

7 December 2020

Contents

- 70th Anniversary of the Korean War: Communist Chinese Offensive, November–December 1950

- 30th Anniversary of Desert Shield/Desert Storm: December 1990

- 75th Anniversary of the Loss of Flight 19

Download a PDF of H-Gram 056 (9.5 MB)

This H-Gram focuses on the Communist Chinese intervention and offensive in Korea in November−December 1950 that resulted in a debacle for UN forces, although the U.S. Marines made an epic fighting withdrawal at Chosin Reservoir. Also during this period, naval aviator Lieutenant (junior grade) Thomas Hudner was awarded the Medal of Honor for his attempt to rescue Ensign Jesse Brown, the first African American carrier aviator. Also covered is the last month of Desert Shield before the transition to Desert Storm combat, and the 75th anniversary of the loss of all five Avengers of Flight 19 and the PBM Mariner sent to search for them.

70th Anniversary of the Korean War

Following the success of the United Nations amphibious landings at Inchon and Wonsan, by mid-October 1950 United Nations forces were driving northward in North Korea toward the Yalu River (the border between North Korea and China/Manchuria). Meeting little opposition, “home before Christmas” fever began to grip U.S. forces despite Communist China’s warning that if UN forces crossed the 38th Parallel (the pre-war dividing line between Communist North Korea and Free South Korea), China would intervene in the war to prevent hostile foreign forces on China’s border. On 19 October 1950, Chinese troops began crossing into North Korea at night undetected, resulting in a surprise defeat (one of the worst of the war) for the U.S. Army at the Battle of Unsan on 1 November.

Yalu River bridges at Sinuiju, North Korea, under attack by planes from USS Leyte (CV-32). Three spans have been dropped on the highway bridge, but the railway bridge (lower bridge) appears to be intact. The Manchurian city of Antung is across the river, in upper right. Photograph is dated 18 November 1950, but may have been taken on 14 November. Official U.S. Navy Photograph, now in the collections of the National Archives. (80-G-423495)

In response to the Chinese incursion, the carriers of Task Force 77 were directed to attack the Korean side of bridges over the Yalu River with the intent to forestall Chinese reinforcement and resupply. These carrier air strikes resulted in the first clashes between U.S. Navy jet fighters and Soviet-piloted MiG-15 jet fighters (with North Korean markings flying from Chinese bases in Manchuria). On 9 November, Lieutenant Commander William Amen became the first Navy pilot (and possibly the first of any pilot) to shoot down a MiG-15, and within a week U.S. Navy pilots downed two more MiG-15s without suffering any losses. The Soviets tried to keep their involvement secret and it wasn’t until the end of the Cold War that the full extent of massive Soviet involvement became known.

Meanwhile, following the Battle of Unsan, Chinese forces disappeared into the mountains and forests of North Korea, resulting in a lull that created a false sense of security by UN Commanders that Chinese intervention would be minimal and easily defeated. However, in one of the greatest intelligence failures (or operational failure to use intelligence) in modern history, the Chinese infiltrated a force of over 300,000 men into North Korea at night through the mountains almost completely undetected. In late November, the Chinese took steps to try to lure UN forces further northward into a giant trap. It worked.

On 27 November 1950, on the heels of the worst Siberian blizzard in a century, the Chinese launched a massive surprise offensive against UN forces in western North Korea (U.S. Eighth Army, South Korean and some British and Turkish units) and against UN forces in eastern North Korea (First Marine Division, Seventh Infantry Division, and South Korean I Corps). The Chinese attack in the west was a debacle, as the Chinese (who fought at night) repeatedly threatened to encircle UN units resulting in the UN units withdrawing to prevent being encircled. This resulted in the destruction of most of the South Korean units and led to a pell-mell retreat by the U.S. Eighth Army all the way back to the 38th, parallel in which unit cohesion broke down and much equipment and weapons was abandoned.

On the eastern side of the North Korean mountains, the brunt of the Chinese offensive hit the First Marine Division, which had been carefully advancing northwards around Chosin Reservoir. Grossly outnumbered, four different groupings of Marines were surrounded and cut off from each other, with only one barely passable road though the mountains (with the Chinese on the heights) connecting them to each other and to the sea, 75 miles distant. Nevertheless, despite the odds, bitterly cold weather, and high casualties, the Marines retained their unit cohesion and fighting spirit, fighting their way back down the road and inflicting far more casualties on the Chinese than were inflicted on them. In what would become known as the Battle of Chosin Reservoir, the Marines would earn 14 Medals of Honor (seven posthumously) and would emerge at the end as an intact fighting force.

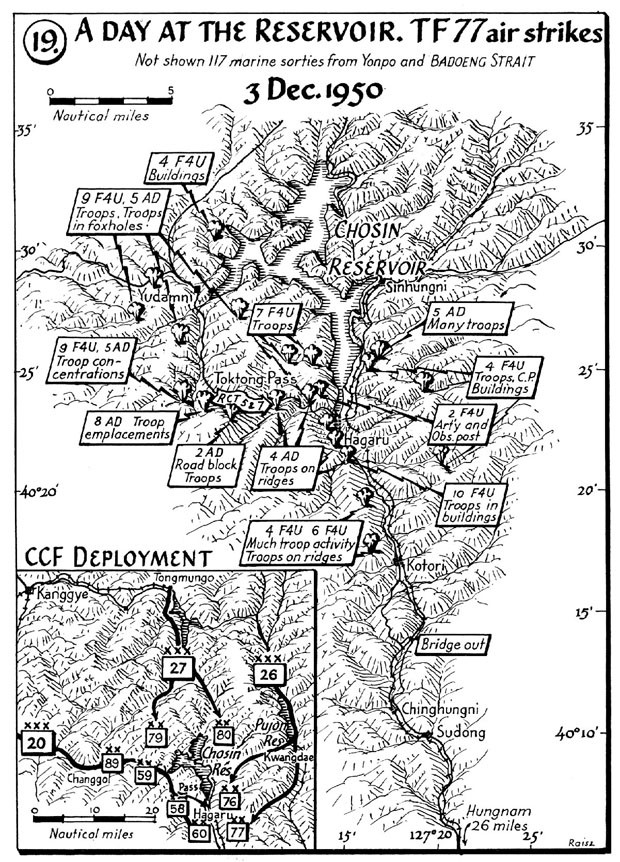

A Day at the Reservoir. Task Force 77 Air Strikes of 3 December 1950.

The Marines at Chosin were aided greatly by close air support from Marine and Navy aircraft flying from U.S. aircraft carriers in the Sea of Japan despite abysmal weather and sea conditions. In one such mission on 4 December 1950 in support of the Marines, Ensign Jesse Brown, the first African-American qualified as a naval aviator, was probably hit by ground fire and forced to crash land his Corsair high in the mountains where he wound up alive but pinned in the wreckage of his burning plane. Brown’s wingman, Lieutenant (junior grade) Thomas Hudner deliberately made a wheels-up landing near Brown’s plane in a desperate attempt to extract Brown from the cockpit. Marine helicopter pilot First Lieutenant Charles Ward made a dangerous attempt to rescue Brown, but neither Hudner nor Ward could get Brown out of the plane before he succumbed to his injuries and hypothermia. Ward was awarded a Silver Star and Hudner would be the first Navy recipient of a Medal of Honor in the Korean War. Jesse Brown was awarded a Distinguished Flying Cross for his previous 20 combat missions.

With the front in the west collapsing, the Supreme UN Commander in Korea, General Douglas MacArthur, ordered the UN forces in eastern North Korea to be evacuated by sea from the port of Hungnam, so they could be transported to the other side of Korea in an attempt to prevent Seoul from falling to the Communists for the second time in the war. The evacuation of X Corps (First Marine Division, Seventh and Third Infantry Divisions) and South Korean I Corps was a massive logistical undertaking by the U.S. Navy, completed on 24 December and dubbed the “Christmas Miracle.”

In the evacuation from Hungnam, 105,000 U.S. and military personnel, 91,000 Korean civilian refugees (including the parents of the current president of South Korea─one ship alone brought out 14,000 refugees) and 17,500 vehicles were extracted, with nothing of military value left behind, all with no loss to the enemy. Regrettably, there was insufficient room for many thousands more refugees desperate to escape the advancing Chinese Army (or what was left of it after the Marines, naval aviation, and subzero temperatures were through with it). As the last ships pulled out, the port facilities in Hungnam were deliberately destroyed in a massive explosion set by U.S. Navy Underwater Demolition Teams.

For more on the Communist Chinese offensive, please see attachment H-056.1. For background on the Korean War and operations from 25 June to 10 November 1950 please see H-grams 050, 054, and 055.

Marines line up on the pier before boarding a U.S. Navy ship for transportation to the Persian Gulf region for Operation Desert Shield. (Records of the Office of the Secretary of Defense, 1921–2008)

30th Anniversary of Operation Desert Shield and Desert Storm: December 1990–January 1991

On 1 December 1990, Vice Admiral Stanley R. Arthur relieved VADM Henry H. Mauz, Jr. as Commander U.S. Naval Forces Central Command/Commander U.S. SEVENTH Fleet.

The month of December 1990 was characterized by a massive deployment of U.S. naval forces while maritime interception operations continued at an intense pace. The first drifting mines were encountered in late December floating south from Iraqi minelaying activity off Kuwait, which U.S. Navy forces could not observe due to restrictions imposed by U.S. Central Command (see H-Gram 055). Provocative Iraq MIRAGE F-1/Exocet flights continued over the northern Arabian Gulf. Iraq also began demonstration launches of long-range surface-to-surface ballistic missiles, with impact in western Iraq. (I will cover Iraqi mine warfare in a comprehensive piece in the February 1991 installment and the “Great Scud Hunt” in the January 1991 installment).

On 1 December, 18 ships of Amphibious Group THREE (PHIBGRU 3) with Fifth Marine Expeditionary Brigade (MEB) embarked departed the U.S. West Coast. USS Ranger (CV-61) deployed from the U.S. West Coast on 8 December. USS Theodore Roosevelt (CVN-71) and USS America (CV-66) deployed from Norfolk on 28 December. On 6 January 1991, USS Saratoga (CV-60) returned to the Red Sea via a record-breaking fifth transit of the Suez Canal following a tragedy off Haifa, Israel, when a chartered liberty ferry capsized on 21 December, resulting in the loss of 21 Saratoga Sailors. On 1 January 1991, USS Missouri (BB-63) arrived in the Gulf of Oman, joining USS Wisconsin (BB-64) in theater. On 12 January, PHIBGRU 3 arrived in the North Arabian Sea, joining Amphibious Task Group TWO, with Fourth MEB embarked, forming the largest amphibious task force since the Korean War. On 14 January, Theodore Roosevelt arrived in the Red Sea and America arrived the next day, joining Saratoga and USS John F. Kennedy (CV-67) already there. America remained in the Red Sea while Theodore Roosevelt continued to the Arabian Gulf. Also on 15 January, USS Ranger arrived in the Arabian Gulf, joining Midway (CV-41) already there, making six carriers deployed for Operation Desert Storm. A total of 108 U.S. Navy ships were involved: 34 in the Arabian Gulf, 35 in the North Arabian Sea/Gulf of Oman, 26 in the Red Sea and 13 in the Mediterranean.

As of 6 December 1990, U.S. and coalition Navy ships had conducted 4,605 intercepts, 569 boardings, and 22 diversions due to prohibited cargo. By 15 January 1991 the numbers were 6,913 intercepts, 823 boardings, and 36 diversions. The most contentious boarding was the Iraqi-flagged freighter IBN Khaldoon, the so-called “Peace Ship,” which was carrying international peace activists as well as prohibited cargo, on 26 December. The boarding team fired warning shots in the air and used a smoke and noise grenade to control the unruly crowd. After being diverted and prohibited cargo offloaded, IBN Khaldoon proceeded to Iraq arriving just in time for the peace activists to be used a “human shields” by Saddam Hussein.

On 4-5 January 1991, USS Guam (LPH-9) and USS Trenton (LPD-14) conducted Operation Eastern Exit, a daring long-range helicopter minimal-notice non-combatant evacuation (NEO) from Mogadishu, Somalia, involving the first inflight night refueling of helicopters by USMC KC-130s. The U.S. ambassador; Soviet ambassador; 65 U.S. citizens, including 36 embassy personnel; and ultimately a total of 281 people, including eight heads of mission and foreign nationals from 30 countries, were successfully evacuated as Mogadishu descended into chaos.

For more on Desert Shield, December 1990, please see attachment H-056.2.

75th Anniversary of the Loss of Flight 19

On 5 December 1945, five U.S. Navy TBM Avenger torpedo bombers from Naval Air Station Fort Lauderdale were lost on a routine overwater navigation flight over The Bahamas Islands. No trace of the planes or the 14 pilots and aircrewmen aboard has ever been found. Fragmentary radio communications indicated compass failure and disorientation of the flight leader as the likely cause leading to the planes running out of fuel and ditching at sea as a bad weather front moved in, hampering the search and any possible survival. A PBM Mariner flying boat launched from Naval Air Station Banana River (now Patrick Air Force Base) to search for the missing Avengers probably exploded in flight with the loss of all 13 men aboard. Radar and visual sighting of a flaming aircraft falling from the sky indicated a sudden catastrophic end for the Mariner; although the exact cause of the Mariner’s loss was not determined, the planes were prone to gasoline vapor accumulating in the bilges. The exact cause of the loss of the five Avengers has also never been determined, however the “mystery” is one of the most enduring in aviation history and quickly became part of “Bermuda Triangle” and “Alien/UFO” lore (see the movie Close Encounters of the Third Kind, which depicts the “return” of Flight 19 by the aliens). I will cover Flight 19 in greater detail in the next H-Gram.