H-Gram 054: The 70th Anniversary of the Inchon Landing and other Navy Operations in Korea (1 September–10 October 1950) and the 30th Anniversary of Desert Shield/Desert Storm (Part 3: October 1990)

22 September 2020

Contents

Download a pdf of H-Gram 054 (6.9 MB).

This H-gram focuses on the daring and decisive USMC/USN amphibious assault on the port of Inchon on the west coast of South Korea, as well as events leading up to it, including the U.S. Navy shoot-down of a Soviet torpedo bomber. It also covers the increasing toll on U.S. ships inflicted by North Korean mines (provided by the Soviets) in the last week of September 1950. This H-gram also includes the continued buildup and operations by U.S. Navy forces during Operation Desert Shield in October 1990.

70th Anniversary of the Korean War

“The Navy and Marines have never shown more brightly than this morning,” said the message from General of the Army Douglas A. MacArthur, the U.S. Commander in Chief, Far East, and Commander in Chief, United Nations Command (CINCUNC), after the brilliantly executed first phase of the amphibious assault on Inchon, South Korea, on 15 September 1950.

Less than a year earlier, Secretary of Defense Louis Johnson had said, “The Navy is on its way out.… There’s no reason for having a Navy and Marine Corps. General Bradley tells me that amphibious operations are a thing of the past. We’ll never have any more amphibious operations. That does away with the Marine Corps. And the Air Force can do anything the Navy can do nowadays, so that does away with the Navy.” Johnson was referencing testimony by General of the Army Omar N. Bradley, the first Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, to the House Armed Services Committee, “I predict that large scale amphibious operations will never occur again.”

On 19 September 1950, Louis Johnson was the one out of a job, replaced by retired General of the Army George C. Marshall. Johnson’s sidekick, Secretary of the Navy Francis P. “Rowboat” Matthews hung on until the summer of 1951, largely marginalized, until he too was finally shoved out the door.

The major amphibious assault at Inchon by United Nations (UN) forces commanded by General of the Army Douglas MacArthur is considered one of the most decisive operations in military history, although the subsequent decision to recapture the South Korean capital of Seoul instead of completely blocking the retreat of North Korean forces after the North Koreans failed to break the UN defense of the Pusan Perimeter came under substantial criticism later. Nevertheless, the strategic situation on the Korean peninsula completely reversed in mid-September 1950 as North Korean forces in the south utterly collapsed and the UN forces went on the offensive. In the case of Inchon, the term “UN” is a bit of a misnomer in that the actual assault was conducted entirely by the U.S. Marine Corps 1st Division (the U.S. Army 7th Division was administratively landed after the Marines had taken Inchon) carried in U.S. Navy ships and enabled by Marine and Navy aircraft from three fleet carriers and two escort carriers, as well as audacious U.S. Navy gunfire support. (The British Royal Navy provided meaningful help.)

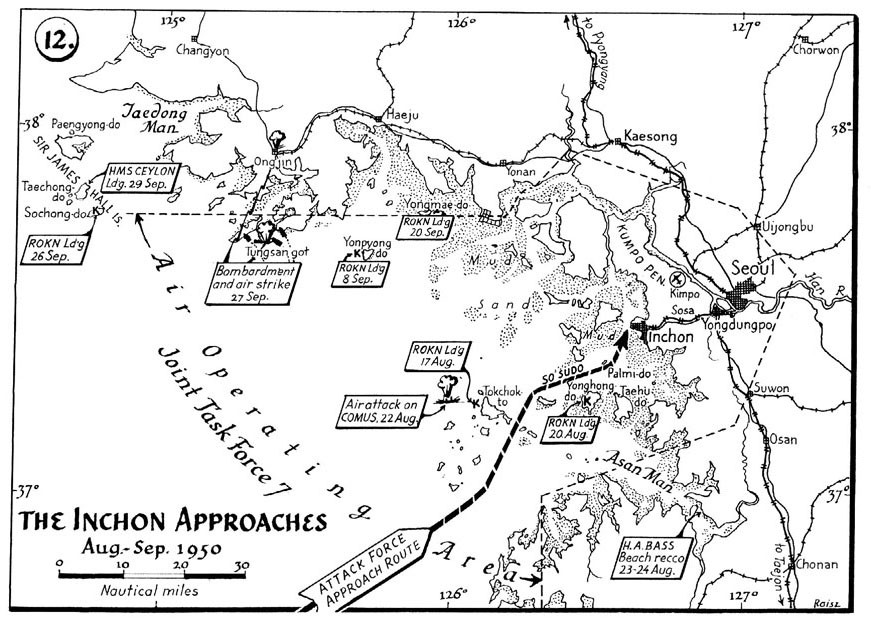

At the beginning of September 1950, the North Koreans launched their largest offensive to date against UN forces pinned into the southeast corner of South Korea in the Pusan Perimeter. For a time, the issue was once again very much in doubt, but the quick reaction by the Task Force 77 fast carriers and Navy aircraft and the fighting spirit of the U.S. Marine 1st Provisional Brigade inflicted heavy casualties, choked off supply lines, and blunted the offensive, which then devolved back in to a stalemate. The planning for an amphibious counterstroke was already underway before the North Korean’s September offensive. The idea was to land an amphibious force on the west coast of South Korea to trap North Korean forces in the South.

The landing at Inchon was MacArthur’s baby. U.S. Navy leaders in the theater were not opposed to an amphibious landing but they were strongly opposed to doing it at Inchon for a long list of militarily sound reasons, of which the primary ones concerned the daunting tide and hydrography challenges, which severely constrained the timing of the operation. Other factors included the unlikelihood of actually achieving surprise; the defensibility of the landing area (the only two “beaches” were actually a seawall leading to industrialized urban areas); inadequate time to conduct any full-scale rehearsal; use of troops that hadn’t even arrived in theater yet; no margin for delay despite it being typhoon season; and the need to bring ships into restricted waters for a point-blank bombardment of the key island of Wolmi Do, which commanded the approaches to both beaches (this would become known in the press as the “Battle of the Sitting Ducks”). After careful study, the best the Navy could say about the plan was that it was “not impossible.”

The greatest advantage of Inchon was that the North Koreans would assume that no one would be insane enough to try to land there, which is what they assumed. MacArthur was utterly unyielding in either the location or the timeline for the assault. After MacArthur convinced the Chief of Naval Operations and gained approval from the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the Navy leaders in the region then proceeded to solve the problems and brilliantly executed the operation with minimal casualties. The Battle of the Sitting Ducks was one of the most audacious in U.S. Navy history. Had the operation been delayed (by a month, due to tides) the North Koreans would have heavily mined the approaches and harbor, but their effort to do so was too little too late.

Inchon wasn’t the only development happening in Korea in September and early October 1950. U.S. carrier aircraft shot down a Soviet torpedo bomber (that fired on Navy aircraft first) that approached the carriers in the Yellow Sea on 4 September, raising the specter of drawing the Soviet Union or Communist China into the war (at a time when, unbeknownst to UN forces, the Soviets were shipping 4,000 sea mines into Korea along with advisors to train the North Koreans on how to best employ them). Carrier aircraft struck targets throughout North and South Korea, constantly using their mobility to thwart enemy reaction, while surface ships bombarded targets on both coasts. These efforts interdicted North Korean supply lines and also contributed significantly to the deception effort for the Inchon landing.

Other key developments included the arrival in theater of a third U.S. fleet carrier, Boxer (CV-21), just in time to participate in the Inchon landing, and then a fourth carrier, Leyte (CV-32) in early October. The battleship, Missouri (BB-63), then the only U.S. battleship still in commission, commenced bombardment operations on her first day of arrival. Late in the month, the U.S. transport submarine Perch (APSS-313) landed British marine commandos ashore in North Korea in a daring and successful mission (at least temporarily) to interdict the Vladivostok-Wonsan railway.

Despite the success of the Inchon operation, the last week of September would prove to be the worst of the war for U.S. and South Korean naval forces as the North Korean mines began to take their toll. Two U.S. destroyers Brush (DD-745) and Mansfield (DD-728) were severely damaged by mines, but saved by superb damage control; Brush lost 13 crewmen and somewhat miraculously Mansfield lost none out of 28 wounded. The small minesweeper Magpie (AMS-25) had no chance when she struck a mine and blew up with a loss of 21 of her 33 crewmen. Two South Korean navy minesweepers also struck mines but survived. The threat of additional losses to mines would become the critical factor in the next major operation of the war, the amphibious assault on the North Korean port of Wonsan in late October, which will be covered in the next H-gram.

For more on the Inchon landing and other Navy operations in Korea from 1 September to 10 October 1950, please see attachment H-054-1. For background on Korean War and operations from 25 June to 1 September 1950 please see H-Gram 050.

30th Anniversary of Operation Desert Shield and Desert Storm, October 1990

In October 1990, as the world’s media focused on the continuing build-up of U.S. Air Force and Army forces in Saudi Arabia (which were nowhere near ready for outbreak of war), U.S. and Coalition naval forces continued vigorous enforcement of United Nations sanctions imposed on Iraq, often under very arduous and tense circumstances. USS Elmer Montgomery (FF-1082) logged the 2,500th intercept on 15 October. On 21 October, USS O’Brien (DD-975) had to fire warning shots to get the Iraqi merchant vessel Al Bahar Al Arabi to stop for boarding.

On 1 October, USS Independence (CV-62) became the first carrier since 1974 to enter the Arabian Gulf. The next day, USS Midway (CV-41) departed Yokosuka, Japan, en route the Arabian Sea, while USS Saratoga (CV-60) and USS John F. Kennedy (CV-67) continued operations in the Red Sea. USS Dwight D. Eisenhower had departed the Red Sea en route to Norfolk at the end of her deployment, somewhat to the consternation of U.S. Central Command, who had a hard time fathoming the idea of U.S. Navy rotations when the Army and Air Force was entirely a one-way flow. On 1 November, Independence commenced a return home upon relief by Midway.

U.S. Navy and Marine Forces conducted Exercise “Camel Sand” in Oman followed by the much larger “Sea Soldier II,” also in Oman, which would be opening moves in a highly successful strategic deception plan (although only a handful of people knew the deception plan). In the first major accident of the war for the U.S. Navy, on 30 October, a major steam leak in the fire room of USS Iwo Jima (LPH-2) killed ten crewmembers.

For more on Desert Shield/Desert Storm – October 1990 please see attachment H-054-2.