H-060-3 The Search for USS Johnston (DD-557)

Samuel J. Cox, Director, Naval History and Heritage Command

In January 2019, I was aboard the research vessel (R/V) Petrel in Ironbottom Sound off Guadalcanal after finding the sunken carrier Wasp (CV-7) (see H-Gram 027) when the ship’s mission director, Mr. Robert Kraft, asked me, “If we could find any ship in the world you wanted, what would it be?” I answered without hesitation, “the Johnston.” Rob whistled through his teeth and said, “Really deep.” I answered, “Really deep.” And we both knew that in the chaotic Battle off Samar, Philippines, on 25 October 1944, the likelihood that anyone was taking very accurate fixes was pretty low. We had learned in the search for the Wasp that open-ocean fixes on where a ship went down could be 10-20 nautical miles (NM) off.

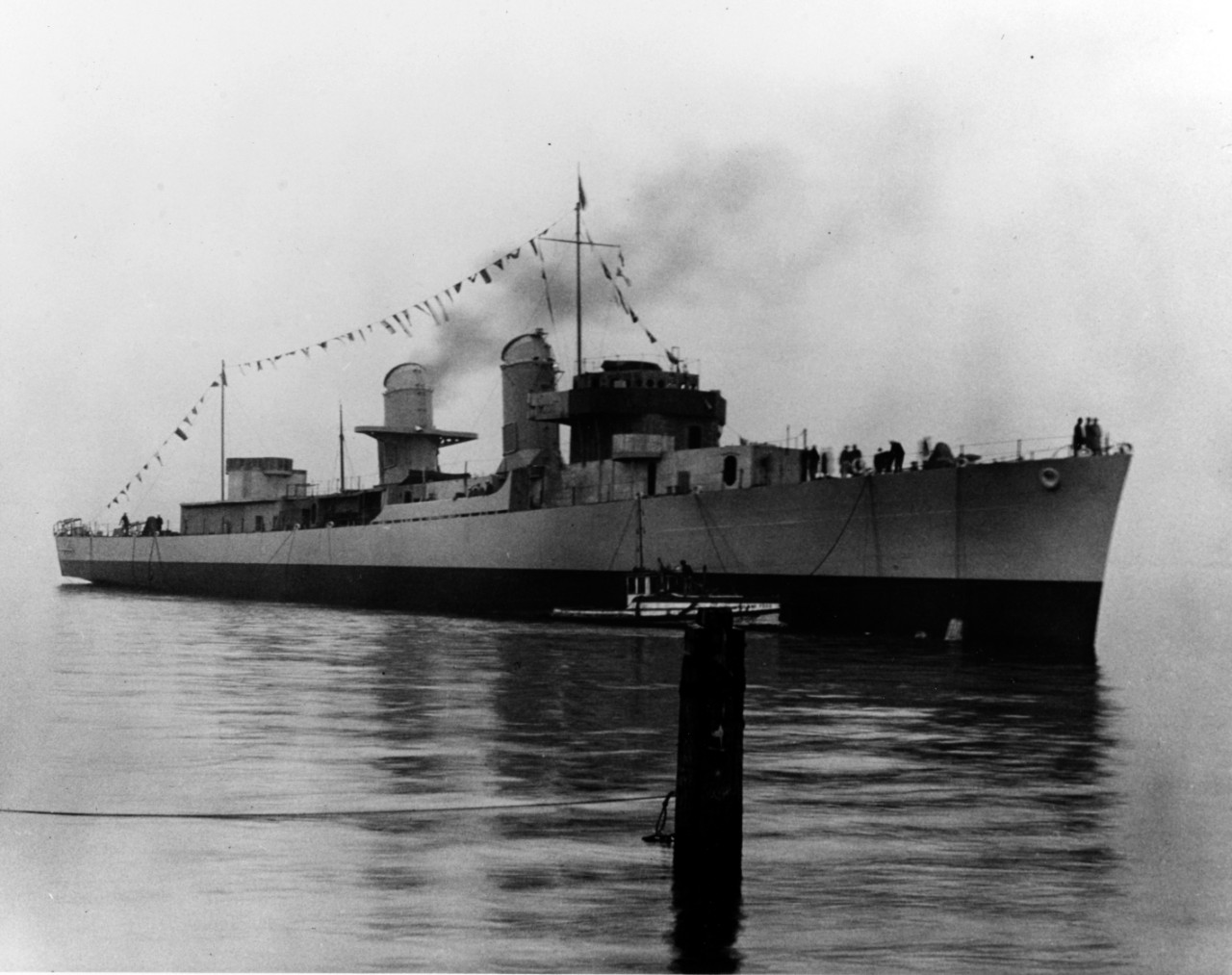

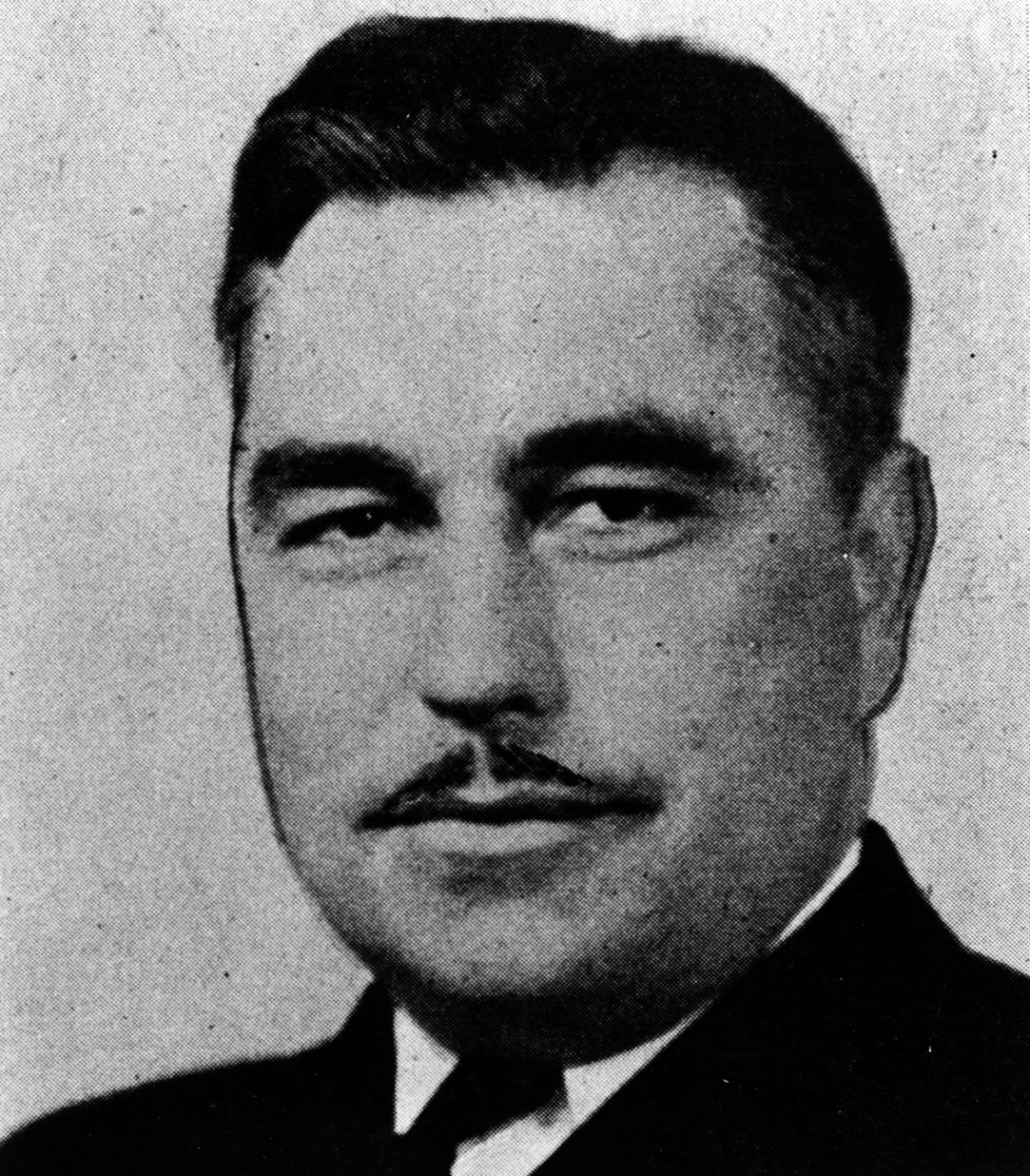

Finding the ship commanded by Commander Ernest Evans, the first Native American awarded a Medal of Honor in the U.S. Navy, in one of the most valiant actions in the annals of naval history would be a tall order. Nevertheless, Rob took me up on the challenge, and later, in 2019, found a wreck off Samar in 20,400 feet of water (the deepest shipwreck ever located, at that time) that we believed was almost certainly Johnston (DD-557) based on her relative position. The debris field was perched at the top of an undersea cliff. The depth was at the extreme limit of Petrel’s Remotely Operated Vehicle (ROV) capability. The wreck was without doubt a Fletcher-class destroyer. The problem with certain identification was that the Hoel (DD-532) went down in the same battle, also in incredibly heroic action against overwhelming odds. No features could be seen (such as a hull number) that would positively identify the wreck.

In analyzing the data provided to the U.S. Navy pro bono by the Petrel’s parent company, Vulcan, Inc., NHHC underwater archaeologists determined that most of the debris field came from the after end of the ship, although the foremast was also in the debris field. The analysts could identify features in the debris field known to be on Hoel, but uncertain as to whether they were on Johnston. Modifications to the foremast were one potential means of discrimination, but in the few photos of Johnston that exist, none were clear enough to determine any difference from Hoel.

Another potentially distinguishing feature in the debris was the gun captain’s shield on what was probably 5-inch gun mount 55. Fletcher-class destroyers had five single 5-inch gun turrets, two superimposed forward (mounts 51 and 52), two superimposed aft (mounts 54 and 55), and one forward-facing mount (53) just forward of mount 54, with a 40-mm antiaircraft gun in between. The gun captain’s shields were installed on the top of lower 5-inch gun mounts to protect the gun captain, if he had his head outside the hatch, from the muzzle blast of any gun overhead. Some Fletcher-class destroyers were constructed with these shields and some had them added later. Configurations also varied. They were most common on mounts 51 and 55 (which had 5-inch gun mounts above them, 52 and 54). Some Fletcher-class destroyers also had the shields on mounts 53 and 54 to protect the gun captains from the 40 mm anti-aircraft gun on the after deck house above the aft 5-inch guns. These shields are readily apparent in photographs of Hoel. In the few photos of Johnston, these shields are either absent or obscured. These shields would have been post-construction add-ons in the case of Johnston, so their absence did not conclusively prove the wreck was not Johnston. We felt confident enough to concur with Vulcan’s announcement in October 2019 that they had found a wreck believed to be Johnston.

It was also clear from Petrel’s extensive search of areas her systems could reach that escort carrier Gambier Bay (CVE-73), destroyer escort Samuel B. Roberts (DE-413), and the probable Hoel were still unlocated, almost certainly in even deeper water than Johnston. During the search off Samar, Petrel found the escort carrier St. Lo (CVE-63), a survivor of the Battle off Samar, only to become the first ship sunk by a kamikaze a couple hours later. Petrel also found the Japanese heavy cruiser Chokai, one of three Japanese heavy cruisers lost in the Battle off Samar or finished off by U.S. air attacks immediately afterward. At the time, I was resigned to the probability that it would be a very long time before we ever found the other ships or could positively confirm the Fletcher-class destroyer as Johnston.

In 2020, Mr. Victor Vescovo approached me with a plan to dive on the “Johnston” wreck site in his deep submersible Limiting Factor, which, despite the name, has no depth limit and has been to the deepest point in all five oceans. (Victor has also climbed Mount Everest and the highest peaks on all six other continents.) NHHC underwater archaeologists were a bit dubious at first, as Victor is not an archaeologist. However, as he is a retired naval officer, I was confident that Victor would treat the wreck with all appropriate respect as a war gravesite, and archaeologist or not; there was still much to be learned and a story of U.S. Navy heroism to be told.

U.S. Navy wrecks are legally protected from disturbance by customary maritime law (unlike merchant ships subject to the right of salvage, warships remain sovereign property in perpetuity) and further by the Sunken Military Craft Act (SMCA). NHHC is the Federal Executive Agent for SMCA. As a general rule, NHHC prefers for U.S. Navy wrecks to be left alone, as many are war graves, as well as being fragile archaeological sites. Nevertheless, under SMCA, NHHC has authority to grant permits for intrusive exploration of a U.S. Navy wreck with sufficient justification for educational, research, environmental, or other official government purpose, although this is granted only rarely. However, under SMCA, anyone can dive on a U.S. Navy wreck without a permit, so long as there is no intent to disturb the wreck. Victor made clear that he had no intention of disturbing the wreck. So, as a private citizen, he technically did not need a permit, nor the Navy’s permission, to dive on the wreck. However, as a retired naval officer, he sought to be as transparent and collaborative with the Navy as possible, which was deeply appreciated.

NHHC has very productive collaborative relationships with reputable privately-funded wreck exploration groups, such as Mr. Robert Kraft, whose research ship Petrel (funded by Microsoft co-founder, the late Mr. Paul Allen) has found the carriers Lexington (CV-2), Wasp (CV-7), Hornet (CV-8), St. Lo (CVE-63), cruisers Indianapolis (CA-35), Juneau (CL-52), Helena (CL-50), and destroyers Ward (APD-16, ex-DD-139), Cooper (DD-695), Strong (DD-467), and Johnston (DD-557), as well as Japanese carriers Akagi and Kaga, battleships Fuso, Yamashiro, Hiei, and other Japanese cruisers and destroyers, among other discoveries. Another productive relationship is with Mr. Tim Taylor and the “Lost 52 Project,” which has located seven U.S. submarines lost during WWII. Another excellent relationship is with the Maritime Heritage Office in the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), which solved the 95-year-old mystery of the disappearance of the fleet tug Conestoga (AT-54) and her 56-man crew, among other discoveries. In each case, these groups have provided their data to the U.S. Navy gratis, and, in turn, NHHC has provided research support for searches and post mission analysis and identification confirmation. This would be the first time working with Victor.

Although the wreck site of what we believed to be Johnston had already been discovered, I considered Victor’s plan worthwhile for several reasons. Although the wreck site had been thoroughly surveyed by Petrel, there was no identifiable hull structure, and it just seemed to me that a significant amount of the ship was missing, and was likely over the edge of the cliff. Second, although my command is very protective of our hallowed wreck sites, NHHC also has a mission to tell an accurate story of U.S. Navy history to as many people as we can possibly reach. There is no better story of Navy heroism to tell the American people than the actions of Johnston and the entire task group of six escort carriers, three destroyers, and four destroyer escorts (radio call sign Taffy 3) in valiant action against an overwhelming Japanese force of four battleships, six heavy cruisers, two light cruisers, and eleven destroyers.

As naval historian Rear Admiral Samuel Eliot Morison said in his comprehensive History of U.S. Naval Operations in World War II, “in no action in its entire history has the U.S. Navy shown more gallantry, guts and gumption than in the hours 0730 to 0930 off Samar” on 25 October 1944. My dad had the entire 15-volume set of Morison’s history (and a library of other naval history books and Jane’s Fighting Ships) and I was looking at the pictures before I could read. From a very young age, I knew the story of the Johnston. While other kids had sports heroes, my childhood hero was Ernest Evans, skipper of the Johnston at Samar. I joined the Navy because I wanted to part of his legacy and others like him.

My interest in Evans continued throughout my career. As a flag officer, I devoted my required diversity outreach efforts to Native American organizations. In 2011, I was given an opening night plenary session speaking spot at the American Indian Science and Engineering Society (AISES) convention and I told the story of Ernest Evans, who was half Cherokee and a quarter Creek. Almost no one in the audience of 700 Native American college students and 300 engineering professionals had heard the story. When I was done, the roar from the standing ovation about brought the roof down, tears streaming down kids’ faces, the works. One of my goals as Director of NHHC is to convince a Secretary of the Navy to name a destroyer USS Ernest Evans.

In short, the story of Ernest Evans and Johnston is one I don’t think can be told too often. It is a story the American people need to hear, both from the perspective of the valor of the U.S. Navy and the contributions of Native Americans to the U.S. Navy. The percentage of Native Americans serving in the U.S. Navy is greater than the percentage of Native Americans in the population of the United States (and the same is true in the other services). I reasoned that if Victor reached the wreck, it would be the deepest wreck dive in history, which would result in more than the usual media attention. I found Victor’s plan to be reasonable, of benefit to the U.S. Navy, and I gave Victor my strongest wish for success, as well as much help as NHHC could legally provide.

Victor and his team conducted extensive preparation for the expedition, both in technical upgrades to his equipment (particularly sonar search capability) and research using all available U.S. and Japanese sources. The research was so thorough that their lead analyst, retired U.S. Navy Lieutenant Commander Parks Stephenson, was able to cross-correlate damage described in Hoel’s after-action report with wreckage observed in the publically released video obtained by Petrel’s ROV. The result of the analysis actually confirmed the wreck was Johnston even before the dive (Hoel’s aftermost 5-inch gun barrel took a direct hit, damage that was not visible in the wreck, but would have been if it were Hoel). Nevertheless, everyone knew the “holy grail” was to find “557” or “532” on the hull. We had learned from previous deep dives on Wasp, Hornet, and St.Lo, at 16 to 17,000 feet that hull numbers would be plainly visible due to the preservation at those depths, unless they had been burned off by fire.

Although the Limiting Factor has no depth limitation, it is limited in the time it can remain on the bottom and the size of the area that can be searched on each dive. The support vessel, Pressure Drop, does not have an Autonomous Underwater Vehicle (AUV) comparable to Petrel’s broad area search capability (although even that is a relative term, in a huge ocean, even Petrel has to be pretty close to the wreck before commencing a search). As a result, Victor’s first two eight-hour dives were a “miss.” Near the end of the third dive, Victor was able to follow a trail of debris down a furrow in the cliff to find the forward two-thirds of a Fletcher-class destroyer almost a thousand feet further down than the original wreck site. The hull number “557” was plainly visible. Victor sent the photo of the hull number to me by e-mail shortly after surfacing. It didn’t take a whole lot of sophisticated analysis to confirm the ship as the Johnston.

A fourth dive was devoted to an extensive video and photographic survey of the wreck, all of which is being provided to the U.S. Navy gratis with no restrictions, along with some sophisticated 3-D modeling of the wreck. NHHC underwater archaeologists will be busy for a while analyzing the data. We do not expect the analysis to significantly change the overall understanding of the battle, but there are indications that will change our understanding to a degree of the last gallant hours of Johnston’s life.

As is the case with previous deep-water dives on U.S. Navy wrecks, no human remains were expected to be seen and none were. In some previous wrecks, shoes and helmets were the only evidence of the crew. In this case, no clothing was seen. Nevertheless, the Johnston is a hallowed site; the last resting place of courageous American Sailors, deserving of as much respect as Arlington National Cemetery. It is legally a war grave. In most cases, the law is the only protection for Navy wreck sites. In this case, the great depths add additional protection. To add even more protection, Mr. Vescovo will not publically reveal the exact coordinates of the wreck, in keeping with NHHC practice to deter pilfering, scavenging, and outright salvaging that has befallen the wrecks of other nations in the Java Sea and South China Sea, and elsewhere.

Following the last dive, the support ship Pressure Drop heaved to, sounded the ship’s whistle, and the ship’s crew laid a wreath over Johnston’s location as a gesture of respect and honor for the Sailors who made the ultimate sacrifice. Mr. Vescovo said, “As a U.S. Navy officer, I’m proud to have helped bring clarity and closure to the Johnston, her crew, and the families of those who fell there.”

Johnston lost 184 of 329 men during the Battle off Samar and in two days in the ocean afterwards. As of today, there is only one survivor of Johnston still alive, so it is incumbent on us to ensure the memory of ship and crew lives on.

For more on the Battle off Samar, Please see H-Gram 036.

Additional Reading:

“Wreckage confirmed as heroic USS Johnston (DD 557)” (1 April 2020, NHHC)