H-Gram 035: Lieutenant (j.g.) George H. W. Bush Shot Down; Mediterranean Theater Catch-up; U-Boat UC-97 on the Great Lakes

6 September 2019

This H-gram covers:

As I have been writing H-grams following along with the 75th Anniversary of World War II, one thing that has amazed me is how the staffs of Admiral Nimitz, General MacArthur, and General Eisenhower could plan and execute a global conflict faster than I can write about it. I am still working on a Normandy wrap-up that includes the great storm off the beachhead and the Battle of Cherbourg, among others.

Download a PDF of H-Gram 035 (3.8 MB). As always, back issue H-grams may be found here, and you are welcome and encouraged to disseminate H-grams so that our Navy can better understand the heroism, sacrifice, and incredible achievements of those whose legacy we are charged to uphold.

75th Anniversary of World War II

Shoot Down of Lieutenant (j.g.) George H. W. Bush

On 2 September 1944, on the third day of carrier strikes by Task Group 38.4 against the Bonin Islands of Iwo Jima and Chichi Jima, the TBM-1C Avenger flown by Lieutenant Junior Grade George H. W. Bush was hit and severely damaged by heavy ground fire while on the run-in to bomb the Japanese radio transmitters on the latter island. Despite the damage, Bush pressed on with the attack and dropped his bombs on target, for which he would be awarded a Distinguished Flying Cross. Bush was able to nurse his damaged plane back out over water before determining that he would be unable to make it back to his carrier (the USS San Jacinto—CVL-30) nor could he control it well enough to safely ditch. Bush’s gunner, Lieutenant (j.g ). William G. White (an intelligence officer, not Bush’s normal gunner) was probably already dead or incapacitated. Unable to communicate with either White, or his radioman (ARM2c John L. Delaney), Bush ordered a bailout. Two chutes were observed by trailing U.S. aircraft. One opened (Bush) and the other (probably Delaney) was a streamer; neither White nor Delaney would ever be seen again. Although injured due to hitting the tail while bailing out, Bush regained consciousness and was able to stay afloat for four hours while U.S. Hellcat fighters overhead kept Japanese boats at bay (all U.S. aircrewmen captured by the Japanese at Chichi Jima during the war were executed, in some cases involving ritual cannibalism). Bush was rescued by the submarine USS Finback (SS-230), spending about a month on board as she continued her patrol and experiencing depth-charge attacks in the process. For more on Lieutenant (j.g ). Bush and a brief history of the TBF/TBM Avenger aircraft, please see attachment H-035-1 “Flight of the Avenger” (a title I have admittedly re-purposed).

Mediterranean Theater Catch-up—Forgotten Valor: Ensign K. Vesole and the “Great Bari Air Raid,” 2 December 1943

On 2 December 1943, 105 German Ju-88 bombers conducted a devastating surprise attack on the Allied port of Bari, Italy. Two U.S. Liberty ships with a cargo of ammunition were hit by bombs and catastrophically exploded, setting off chain reactions throughout the harbor, which was quickly covered by flaming fuel oil. About 28 cargo ships were sunk, including five U.S. Liberty ships, one of which (SS John Harvey) was carrying a secret cargo of 2,000 mustard gas bombs, which added to the thousands of casualties and was the only known poison gas incident of the war. As many as 2,000 crewmen on the ships, dockworkers, and civilians in the city were killed. About 75 U.S. merchant seaman and 50 U.S. Navy Armed Guards were killed in the attack. Polish immigrant Ensign “Kay” Vesole, USNR, commanding officer of the Armed Guard on SS John Bascom (the first ship to open fire on the German bombers), was awarded a posthumous Navy Cross for extraordinary heroism. According to Navy historian Samuel Eliot Morison, “This was the most destructive enemy air raid on shipping since the attack on Pearl Harbor.” Please see attachment H-035-2 for more about Ensign Vesole and the Bari air raid.

Operation Shingle: The Allied Landings at Anzio, Italy, January–June 1944

British Prime Minister Sir Winston Churchill would later say of the Allied amphibious assault at Anzio, “I had hoped we were hurling a wildcat onto the shore, but all we got was a stranded whale.” How much responsibility Churchill bore for the ill-conceived operation is beyond the scope of this H-gram. Operation Shingle was intended to be an amphibious end-run around the German defense lines that had bogged down the Allied advance between Naples and Rome in the winter of 1943–44. Although the initial landings on 23 January 1944 caught the Germans by surprise and went pretty well, the enemy reacted swiftly with superior numbers of forces, and pinned down the Allied force on a narrow beachhead until late May of 1944. This resulted in about 4,500 Allied soldiers being killed during the stalemate, including 454 U.S. soldiers who were lost on British LST-422, which was sunk by a German mine.

Incessant German air attacks, including many using radio-controlled glide bombs, and later attacks by U-boats, inflicted a steady drain on Allied ships, with many damaged and several painful losses. The Royal Navy suffered the most, losing two cruisers, three destroyers, and numerous amphibious ships, plus a hospital ship bombed and sunk. U.S. losses were confined to an LST torpedoed by a German submarine, minesweepers lost to mines, amphibious craft to various causes, and two Liberty ships lost in ammunition explosions due to air attack. Naval gunfire support proved critical in blunting many German counter-attacks that at times seriously threatened the narrow Allied beachhead. Finally, with the aid of naval (especially supplies and reinforcements) and air superiority, the Allied force was able to break out of the beachhead in late May and Rome fell on 4 June 1944. For more on Operation Shingle, please see attachment H-035-2.

Convoy Battles Along the Coast of Algeria, April–May 1944

German submarines and aircraft continued to take a toll on U.S. warships escorting convoys in the western Mediterranean in the spring of 1944, although it was essentially the Germans’ last gasp. On 11 April 1944, the destroyer escort USS Holder (DE-401) was hit and severely and irreparably damaged by a torpedo from a German aircraft. Saved by her crew, Holder would be towed to New York City, where her stern would be removed to replace that of the USCG-manned destroyer escort USS Menges (DE-320), whose stern had been badly mangled by a German submarine-launched acoustic homing torpedo off Algeria on 3 May 1944. On 20 April 1944, a large German air attack struck an eastbound Allied convoy off the coast of Algeria; the U.S. Liberty ship SS Paul Hamilton exploded and sank, with the loss of all 580 merchant seamen, Navy Armed Guard, and mostly U.S. Army Air Force ground personnel aboard. In addition, the destroyer USS Lansdale (DD-426) was torpedoed and sunk in the air attack; one of Landsdale’s survivors, executive officer Robert Morganthau, would go on to be the longest-serving Manhattan district attorney (35 years). On 5 May 1944, destroyer escort USS Fechteler (DE-157) was sunk by a German U-boat off Algeria, the last major U.S. warship lost in the Mediterranean. Despite these losses, hundreds of Allied cargo ships were safely escorted to Italy and other ports in the Mediterranean. For more on the convoy battles off Algeria, and the distinguished service of Robert Morganthau, please see attachment H-035-2.

Operation Dragoon, the invasion of southern France on 15 August 1944, will be covered in a future H-gram.

100th Anniversary of World War I

U-Boat UC-97 on the Great Lakes

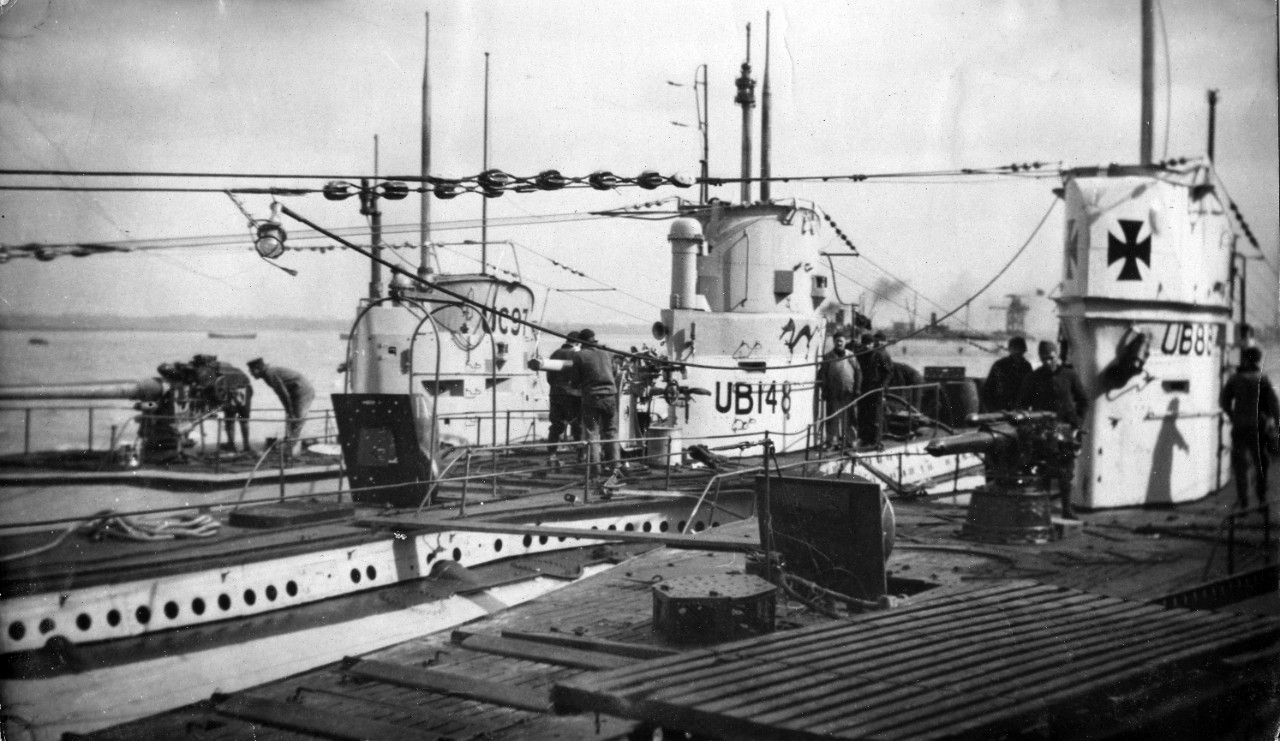

In August 1919, the submarine USS UC-97 arrived in Chicago, where she continued to be the biggest sensation on the Great Lakes in decades, visited by many thousands of American citizens. Commanded by Lieutenant Charles A. Lockwood (future vice admiral in command of U.S. submarines in the Pacific in World War II), UC-97 was flying the U.S. national flag over the flag of Imperial Germany, the international signal for a captured vessel. UC-97 was a German U-boat surrendered to the British shortly after the armistice went into effect in November 1918. The British then allowed other Allied nations to take possession of several U-boats (with the proviso that the U-boats be sunk upon conclusion of study and test ). UC-97 was one of six provided to the United States, which then conducted an epic and harrowing crossing of the Atlantic under their own power.

Upon arrival in the United States, the former German submarines visited numerous U.S. cities—one submarine operated on the West Coast (via the new Panama Canal)—on a highly successful war bond and recruiting drive. UC-97 proceeded up the St. Lawrence Seaway to the Great Lakes (provoking an international incident with the Canadians when she refused to fly the Union Jack) before visiting cities on all the Great Lakes (except Lake Superior). After being stripped of all useful material, UC-97 was sunk in Lake Michigan as a target in 1921 and then forgotten. So forgotten, that even in the 1960s, the Naval Historical Center (predecessor of Naval History and Heritage Command) dismissed stories of a German U-boat in Lake Michigan as rumor. However, she is still there today, within sight of the skyscrapers of Chicago. For more on UC-97 and the other five U-boats (including one sunk by Commander William F. Halsey), please see attachment H-035-3.