H-003-3: The Valor of the Asiatic Fleet

H-Gram 003, Attachment 3

Samuel J. Cox, Director NHHC

20 February 2017

The following is not meant to be a comprehensive discussion of every noteworthy act of valor by a ship of the U.S. Asiatic Fleet. There are too many to choose from. Among those I don’t discuss include the light cruiser USS Marblehead (CL-12) and her extraordinary damage control after crippling bomb damage in the Flores Sea on 4 Feb 42, and her epic solo return voyage to New York City via the Indian Ocean. Another is the destroyer USS Peary (DD-226), which barely survived the bombing at Cavite, barely survived numerous other encounters with Japanese aircraft, subs, and ships, but had the misfortune to be the largest warship in port Darwin, Australia when 188 Japanese planes from four carriers attacked, yet she went down with guns blazing. And then there was the USS Stewart (DD-224,) put into the drydock at Surabaya, Java to repair battle damage, only to topple off improperly set blocks and subsequently subject to destruction by demolition charge; however, the Japanese salvaged and repaired her and put her in their own service, leading to numerous mysterious sightings of a U.S. four-piper destroyer far behind Japanese lines during the war. Nor do I discuss the multiple U.S. submarines that endured incredible poundings by Japanese depth charges, for little result; some survived, but USS Sealion(SS-195) was lost at Cavite to bombs; USS Shark (SS-174) was lost with all hands, and USS Perch (SS-176) was lost, but all hands were rescued by the Japanese and taken prisoner. In particular, it is important to note that in numerous cases, acts of valor are unknown because there were few or no surviving witnesses.

On 3 Dec 1941, ADM Hart received orders from President Roosevelt himself to dispatch the armed yacht USS Isabel, by name, to conduct a reconnaissance of Japanese shipping gathering off Cam Ranh Bay, Japanese-occupied French Indo-China (Vietnam) despite the fact that Hart’s PBY reconnaissance aircraft had been accurately tracking the Japanese ships for days. Two other vessels were also ordered to conduct similar missions, but were not ready before the start of the war. The reason for Roosevelt’s order remains a mystery, leading to years of conspiratorial speculation that the mission was intended to provoke the Japanese into “firing the first shot,” which in this case might actually be true. The Isabel was recalled just as she came in sight of the Vietnamese coast.

For the next three months, the Isabel was assigned all manner of hazardous tasks, such as leading destroyers at night through poorly charted waters; leading destroyers at night through unfamiliar minefields; sent alone without air cover to deliver critical translators to the Dutch RADM Doorman’s strike force; sent to rescue a large personnel transport under attack by a Japanese submarine, and sank the submarine; sent on numerous other wild-goose chases, and by accident, became the last ship of the Asiatic fleet to leave Java, evading a major Japanese force and surviving a tropical cyclone in a successful escape to Australia. Neither the skipper nor the ship received any kind of commendation whatsoever, except the one battle star awarded to all ships of the Asiatic Fleet.

During the devastating Japanese air raid on Cavite, the only major U.S. Navy base in the Far East, lack of fighter cover and lack of AAA that could reach the altitude of the 54 Japanese bombers, enabled the Japanese to systematically destroy virtually the entire base on 10 Dec 41. The result was an immense conflagration along the entire waterfront. Although ADM Hart had dispersed most of the Asiatic Fleet, the destroyer USS Peary (DD-226) was in repair status, and was immobilized by bomb damage that killed or injured many of her crew, including the commanding officer. Braving the inferno (and that fact that somewhere in the inferno, the ammunition dump had not yet gone up; the ammo dump seemed to be the only thing the Japanese missed), the minesweeper Whippoorwill made repeated, and eventually successful, efforts to pull Peary away from the quay.

On the other side of the small peninsula, the submarine USS Seadragon (SS-194) was trapped between the raging fires and the outboard submarine USS Sealion (SS-195) sinking as result of Japanese bomb hits. Like the Whippoorwill, the USS Pigeon made numerous attempts to pull the Seadragon free, despite the danger, and succeeded. After a frustrating first patrol, due to faulty torpedoes, Seadragon evacuated the members of the Intelligence/Code-breaking center (Station Cast), including future VADM Rufus Taylor, from Corregidor to Australia.

With the rapid achievement of Japanese air superiority, ADM Hart’s plan to operate submarines from Manila Bay from the submarine tenders became untenable, and the tenders USS Holland (AS-3) and USS Otus (AS-20) were ordered withdrawn much further south. USS Canopus drew the short straw, and was ordered to the Bataan Peninsula where she provided extensive repair and machine shop capability to U.S. Army forces tenaciously defending the peninsula. After being damaged in an air attack, the Canopus was deliberately given a significant list, with painted damage, and smoke pots; giving her the appearance of being sunk to forestall further bombing; the crew did their work afloat at night, and as much on shore as possible. For the most part, the ruse worked.

When a significant Japanese force made an amphibious landing behind U.S. lines, the Army counter-attacked and trapped the Japanese, who holed up in significant numbers in caves along the shore that could not be hit from landward. In response, the crew of Canopus created “Uncle Sam’s Mickey Mouse Battle Fleet” consisting of several launches fitted with armor plate and field guns, to hit the Japanese from seaward, which worked, although the “Mickey Mouse Battleships” eventually succumbed to air attack.

About 150 of Canopus’ crew, were combined with plane-less ground crews, and some Marines to form the Naval Battalion, which performed surprisingly effectively by spooking the Japanese into thinking it was some kind of suicide unit, because they thrashed about the jungle in brightly colored uniforms (whites boiled in coffee comes out as mustard yellow,) while drawing Japanese fire by talking loudly and smoking cigarettes at night. More importantly, the Navy battalion did not realize that it was supposed to withdraw when flanked, instead holding their ground and sweeping up infiltrators in the morning, confounding the Japanese. When Bataan was surrendered in April 42, the USS Canopus was scuttled, and her crew fought valiantly in the last-ditch defense of Corregidor Island.

On 31 Dec 41 in the Molucca Sea, the small (950 ton) WWI-vintage seaplane tender, USS Heron came under eight hours of near continuous Japanese air attacks, initially by one four-engine flying boat, then six four-engined flying boats (dropping as many as 12 100lb bombs each in repeated runs), and then by five twin-engine land-based bombers. With a speed of only 11 kts, and only two obsolete 3” guns and 50 cal. machine guns for protection, the Heron managed to avoid all bombs, even damaging several Japanese aircraft, before a bomb finally hit on top of the mainmast, seriously damaging the ship, killing two and wounding 28, almost half her crew. Despite the damage and heavy casualties, the crew continued to fight valiantly as three more four-engined flying boats closed in for a textbook “Hammer and Anvil” torpedo attack (one plane attacking from the port bow, one from the starboard bow and one from the port quarter, so that no matter which way the ship turned to evade, she would bring her beam to at least one torpedo.) And yet, the Heron skillfully evaded all three torpedoes, and so damaged one of the flying boats that it was forced to land on the water. Heron then sank the massive flying boat with her guns, while being strafed by the other two, and even attempted to rescue eight surviving Japanese aircrewmen, who refused to be rescued.

Although historian RADM Samuel Eliot Morison considered the performance of the six PT-Boats of MTB -3 to be over-rated, given the severe handicaps that they operated under, the crews of MTB-3 acquitted themselves with distinction. With virtually no maintenance capability, no spare parts, limited fuel that was frequently bad, lack of ammunition, operating regularly at night in poorly charted shallows, torpedoes that repeatedly ran hot in the tubes (often more a danger to themselves than the Japanese,) under constant air attack, and surrounded by fast Japanese destroyers that could run down a PT-Boat (as PT-109 learned later) just surviving was a major accomplishment. Yet, the PT-Boats repeatedly harassed the Japanese.

By April 1942, all six boats had been lost to grounding or enemy action, but not before General MacArthur decided he would rather take his chances on a PT-Boat than a submarine, when he was ordered by President Roosevelt to leave the Philippines. In a harrowing journey beginning 11 Mar 42, two PT-Boats carried MacArthur, his wife, maid, senior staff, much luggage, and RADM Rockwell (senior Navy officer still in the Philippines) from Corregidor to Mindanao for further onward flight by plane. The two boats then went back to a different island, and evacuated Philippine President Manuel Quezon (Although the Philippines was not independent, it had already been granted substantial autonomy by the U.S., a factor that significantly affected MacArthur’s decision-making on the first day of the war, although that is another story.)

Patrol Wing TEN, suffered some of the highest casualties of any U.S. Navy unit in WWII. Initially starting with 28 PBY Flying Boats and ten utility aircraft of varying types, PATWING TEN was reinforced over the next three months; of the 44 PBY’s that served in the squadron, all but five were lost, and all but one of the utility aircraft were lost. Many PBY’s were shot down or destroyed at anchor in the opening days of the war, resulting in a critical loss of operational situational awareness by U.S. commanders. As a result of the PBY losses, ADM Hart was forced to evacuate from the Philippines to Java via a submarine, loosing ten days of command and control in the process.

Despite severe losses, the PBY’s repeatedly attempted reconnaissance flights, and after the surviving Army Air Force B-17 Flying Fortress bombers were withdrawn, the PBY’s were pressed into service as bombers, with high losses. With a full bomb load, the PBY’s could only fly about 85 Kts and could not climb above Japanese AAA. In one attempted raid against a Japanese shipping concentration at Jolo, Philippines, on 26 Dec 41, four of six PBY’s were lost.

Amongst numerous epic studies in survival by downed PBY crews was the one involving a PBY piloted by LT Thomas Moorer, future CNO and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Launching from Darwin on 19 Feb 42 on what was supposed to be a routine mission, Moorer was jumped by Japanese fighters escorting an inbound raid of 188 aircraft from four aircraft carriers. With his radio shot away, Moorer was unable to warn Darwin of the impending devastating attack. Although wounded, Moorer skillfully ditched the disabled aircraft, and his crew abandoned it before it was strafed and destroyed. Moorer and his crew were subsequently rescued by a Filipino freighter that had been chartered to take supplies to Corregidor (by then a suicide mission if there ever was one.) That ship was then bombed and sunk. One of Moorer’s crew was killed in the water by a Japanese near miss. Moorer found himself in charge of the ship’s lifeboats, navigated his way to an island off the Australian coast, attempted an aborted foot march across the island, before being rescued by an Australian patrol boat, which was also bombed, but fortunately not sunk.

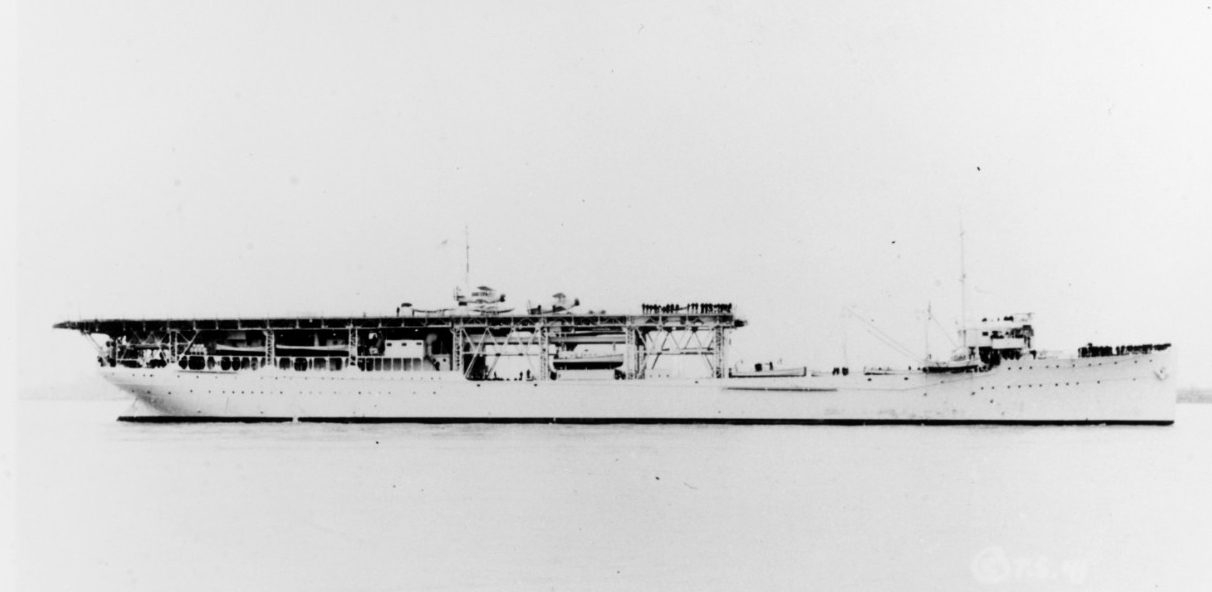

In response to intense political pressure from the Netherlands Government-in-Exile, the U.S. agreed to send a shipment of P-40 fighter aircraft, with pilots and ground crew, to Java. The U.S. Navy’s first aircraft carrier, by then converted to a seaplane tender with half her flight deck removed, the USS Langley was given the mission to carry 32 assembled P-40’s from Australia to Java in late Feb 42. The mission was by then too little too late, but no one would call it off. By then the Japanese had complete mastery of the air over Java, and had even shot down 40 allied aircraft in a single day. But the situation was so desperate, that Dutch VADM Helfrich (in charge of allied naval forces after ADM Hart’s recall) ordered the Langley to make a daylight run into the south Java port of Tijilatjap on 27 Feb 42. VADM Glassford, commander of U.S. naval forces under Helfrich, concurred with the suicidal order. Tijilitjap did not even have an airfield, and would require bulldozing of buildings in the port city to widen the roads to get the aircraft to an open field, where they might be able to take off. Japanese bombers solved that problem.

Although not very maneuverable, and unstable due to the load of fighters, the Langley’s CO adroitly avoided the first bomb runs, but the Japanese were skillful too, and the Langley was hit in quick succession by five bombs. Although the crew tried valiantly to save the ship, it became apparent that the Langley would never reach the port, so the ship was abandoned. Subsequent attempts to hasten its sinking with friendly torpedoes and gunfire failed, and the ship was left adrift to eventually sink on its own.

The great majority of Langley’s crewmen, and the Army pilots, were rescued by U.S. destroyers, before being transferred to the oiler USS Pecos, which was then bombed and sunk by 36 aircraft from four different Japanese carriers. The destroyer USS Whipple (DD-217) attempted to rescue as many survivors as possible, in between attacks on a Japanese submarine, but was forced to break-off the effort during the night. Some 230 survivors were rescued, but over 400 were left behind in the water, of whom all ultimately perished.

After the events, VADM Glassford’s report stated that CDR McConnell’s actions in failing to save his ship were not in the best tradition of the U.S. Naval Service. ADM Ernest J. King, never known to be merciful, reviewed the report, non-concurred with Glassford’s findings, and ordered that McConnell’s record be expunged of any derogatory material.

The USS Pope (DD-227) missed the Battle of the Java Sea due to an engineering casualty. Because Pope still had a full load of torpedoes, she was assigned to escort the damaged British heavy cruiser HMS Exeter. The four surviving U.S. destroyers from the Java Sea battle, their torpedoes expended, were ordered to leave the Java Sea via the Bali Strait (too shallow for Exeter) which they did after a brief firefight with several surprised Japanese destroyers.

The Exeter, Pope, and the British destroyer HMS Encounter, attempted to take a circuitous path just south of Borneo and then to the Sunda Strait in an effort to avoid Japanese surface combatants. Instead, at daybreak on 1 Mar 42, they ran into four Japanese heavy cruisers (including the two victors of the Java Sea Battle, which were low on ammunition) and several destroyers. In an hours-long chase, Encounter and Pope repeatedly attempted to keep the Japanese at bay with torpedoes and guns, until Exeter received a crippling mobility kill. The CO of Exeter ordered Encounter and Pope to try to escape. Encounter refused the order and stood by Exeter until the very end, and both ships went down together.

After several more hours, subject to repeated near misses from Japanese aircraft that put the Pope in sinking condition, coupled with a boiler casualty that greatly reduced her speed, and with all torpedoes expended, and all but 20 rounds of main gun ammo expended, the CO ordered the ship abandoned and scuttled; miraculously, Pope’s only KIA of the battle was due to the demolition charge to destroy the ship’s communications gear.

In what would become an increasingly rare display of chivalry, all of Pope’s 151 survivors were picked up by a Japanese destroyer (as were almost all the survivors of Exeter and Encounter) and treated relatively well. Once ashore in the prison camps the hell began and only 124 of Pope’s crew survived captivity, including LT Richard “Bull” Antrim who was awarded a Medal of Honor for risking his life to save other prisoners.

On 1 Mar 42, the powerful force of Japanese aircraft carriers, battleships, and heavy cruisers operating south of Java to destroy Allied shipping attempting to flee from Java, received a report from a scout plane that the force was being “pursued” by a lone Allied ship. A Japanese force of two battleships, IJN Hiei and IJN Kirishima, and two heavy cruisers, IJN Tone and IJN Chikuma were sent to investigate, discovering that the pursuer was the destroyer USS Edsall, which had received orders to transit north toward Java in a vain effort to escort some allied ships. In the running battle that followed, Edsall returned Japanese fire and launched torpedoes, narrowly missing the Tone. The Japanese fired over 1,300 14” and 8” shells at the destroyer before calling in air support from 26 carrier-based Kate bombers, before the Edsall finally lost power and was smothered in an avalanche of shells and bombs.

A short film clip and later “still” from the film (attachment H-003-6), taken from Tone, shows Edsall’s last moments as she is literally being blown out of the water. Misidentified in subsequent Japanese propaganda films as “HMS Pope,” the famous picture has subsequently been misidentified in many other books as the “USS Pope,” her sister, lost the same day. Eight of Edsall’s survivors were rescued by the Chikuma, but all were subsequently executed while in Japanese prison camps. None of Edsall’s 185 crewmen survived the war.

On the night of 2 Mar, south of Java, a Japanese force of battleships and heavy cruisers was perplexed into indecision by the bizarre and unexpected behavior of what they identified as a lone Omaha-class light cruiser (like the USS Marblehead (CL-12)) heading directly toward the vastly superior Japanese force, making no attempt to take evasive maneuvers. Like the U.S., the Japanese regularly over-estimated the size of opposing ships. The Japanese hesitated, awed by the “samurai” behavior of the lone ship, before opening fire at close to point-blank range. The unidentified ship returned fire before being smothered by 170 8” rounds. The ship was the USS Pillsbury (DD-227), heading toward a rendezvous with the U.S. light cruiser USS Phoenix (CL-46.) It’s possible the Pillsbury mistook the lead Japanese heavy cruiser for the Phoenix, and Japanese sources state that Pillsbury immediately turned away when they opened fire, which would support that contention. It is also possible that the Pillsbury, realizing that she could not outrun such a force, attempted to close for a surreptitious night torpedo attack (holding gun fire as at the Battle of Balikpapan until after expending torpedoes – Pillsbury had previously severely damaged the Japanese destroyer IJN Michishio.) Given how other U.S. ships responded when faced with hopeless odds, I’d prefer to give the crew of the Pillsbury credit for an attack. But the answer will never be known, because there were no survivors.