H-071-3: Forgotten Valor—The Sacrifices of USS Neosho and USS Sims

On Sunday morning, 7 December 1941, the fleet replenishment oiler Neosho (AO-23) was at the aviation fuel pier for Naval Air Station Ford Island, having nearly completed off-loading cargo containing high-octane aviation gasoline brought on the latest shuttle from the West Coast. With most of the oiler’s tanks holding only highly volatile fumes, Neosho was essentially a giant bomb moored among “Battleship Row” on the east side of Ford Island. At the mooring off Neosho’s port bow was the battleship California (BB-44), flagship of the battle fleet. Off Neosho’s starboard quarter were the battleships Maryland (BB-46) and Oklahoma (BB-37), nested together with Oklahoma to outboard. The two battleships were effectively blocked in due to Neosho’s length (513 feet).

The commanding officer of Neosho was Commander John Spinner Phillips, a United States Naval Academy (USNA) graduate of the class of 1918 with an accelerated graduation in 1917 due to World War I. During that war, Phillips served aboard the armored cruiser South Dakota (later designated ACR-9) escorting convoys across the Atlantic. He served in a variety of assignments during the interwar period, including duty as an instructor at the Naval Academy (twice) and as a professor of naval science and tactics at Northwestern University, teaching naval reservists. He was the second commanding officer of Neosho, and Neosho was his first command.

The first Japanese bomb hit the mud near the seaplane ramp at the south end of Ford Island at about 0757, not far from Neosho. Within minutes, 24 Japanese Nakajima B5N “Kate” torpedo bombers from carriers Akagi and Kaga came streaming down Southeast Loch in pairs, launching torpedoes at Battleship Row. At the same time, 16 Kates from Hiryu and Soryu attacked from the west side of Ford Island, the usual location for U.S. aircraft carriers, which were not in port. Six of the Kates attacked the west side anyway sinking the target battleship Utah (AG-16). Others attacked 1010 Dock damaging light cruiser Helena (CL-50) and sinking minelayer Oglala (CM-4) while some circled around to attack the battleships on the east side of Ford Island.

Most of the torpedo bombers took the easy shot at Oklahoma and West Virginia (BB-40). California at the south end was hit by two torpedoes, and Nevada (BB-36) at the north end of Battleship Row was hit by one. As the Japanese torpedo bombers administered gross overkill on the capsizing Oklahoma and the sinking West Virginia, five of the last nine torpedo bombers from Kaga paid the price, downed by antiaircraft fire that the Japanese described as astonishingly heavy. However, of the 30 or so torpedo bombers that attacked the battleships on the east side of Ford Island, not one thought that Neosho was worth a torpedo.

Had Neosho been struck by a bomb or a torpedo, the likely result would have been a catastrophic explosion on the order of that of the magazine of battleship Arizona (BB-39). Such an explosion would have had a devastating effect on both the topsides of the nearest battleships and the men struggling to survive the capsized Oklahoma, and would have greatly added to the casualty toll of the attack. Although this apparently didn’t cross the minds of any Japanese pilots, one person who was acutely aware of this danger was Commander Phillips. Neosho’s crew quickly opened fire with the weapons they had (including rifles), but like most of the outdated antiaircraft weapons at Pearl Harbor, these were ineffective. Despite bombs, torpedoes, and strafing hitting all around, Commander Phillips knew he would have to move his ship.

Commander Phillips coolly gave the order to get underway. It took some time to get up steam, and the mooring lines had to be cut with axes because there was no one to tend them ashore. By 0842, as the first wave attack was waning, and without the assistance of tugs, Phillips first backed the ship to within a few feet of Maryland and the capsized Oklahoma without hitting either. Phillips then ordered ahead with left rudder, avoiding hitting the burning and slowly sinking California.

As Nevada commenced the famous run down Battleship Row, Neosho was already underway, crossing the harbor to Southeast Loch as the second wave attack came in. Nevada attracted the most attention from the second wave (all dive bombers, no torpedo bombers). Neosho’s gunners probably downed one aircraft (it’s impossible to be sure, given the volume of fire from so many ships) and damaged or drove off three others. Three Neosho crewmen were wounded by strafing. By the end of the second wave, Neosho had moored alongside Castor (AKS-1) at Berth M-3 near Merry’s Point, essentially unscathed.

For his actions during the attack on Pearl Harbor, Commander Phillips was awarded the Navy Cross (one of 51 awarded for the battle):

The President of the United States of America takes pleasure in presenting the Navy Cross to Commander John Spinning Phillips, United States Navy, for extraordinary heroism and distinguished service in the line of his profession as Commanding Officer of the Fleet Oiler U.S.S. NEOSHO (AO-23), during the Japanese attack on the United States Pacific Fleet in Pearl Harbor, Territory of Hawaii, 7 December 1941. At the time of the attack the U.S.S. NEOSHO was moored alongside the gasoline dock, Naval Air Station, Pearl Harbor, and had just completed discharging gasoline at that station. When fire was opened on enemy planes, Commander Phillips realized the serious fire hazard of remaining alongside the dock as well as being in a position that prevented a battleship from getting underway, got underway immediately. Mooring lines were cut, and without the assistance of tugs, Commander Phillips accomplished the extremely difficult task of getting the ship underway from this particular berth in a most efficient manner, the difficulty being greatly increased by a battleship having capsized in the harbor. The conduct of Commander Phillips throughout this action reflects great credit upon himself, and was in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.

See H-Gram 066 for a more comprehensive treatment of the attack on Pearl Harbor.

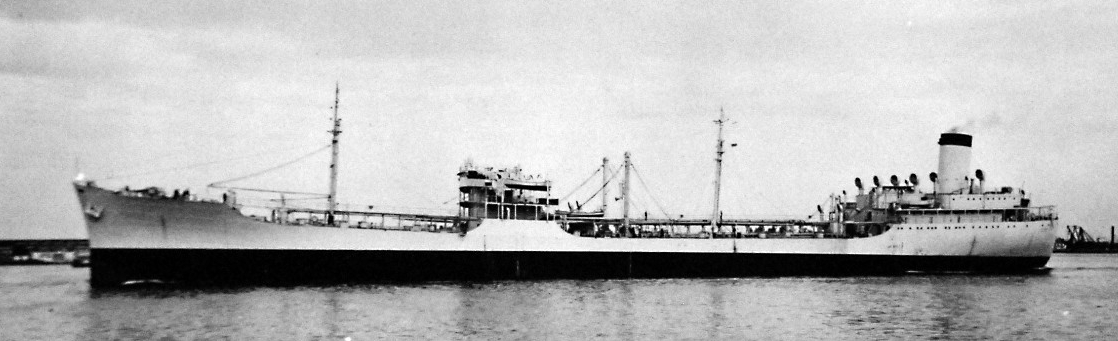

Neosho

Neosho was laid down on 22 June 1938 as a national security tanker. These tankers were built for the U.S. Merchant Marine but to Navy specifications so that they could quickly be militarized for naval service. The construction of Neosho was funded by Standard Oil, but the U.S. Navy paid for a more powerful engineering plant that would enable Neosho to achieve speeds of 18–20 knots so the tanker could serve as a fleet replenishment oiler.

Neosho was launched on 29 April 1939, with Elizabeth Land as the sponsor. Her husband, Vice Admiral Emory S. Land, had retired from the U.S. Navy in 1937 from a distinguished career that included many naval architecture developments, particularly for U.S. submarines. He played a key role in the development of the S-class submarines, intended to be fast enough on the surface to operate with the fleet. In 1938, he accepted a position as chairman of the U.S. Maritime Commission. In that capacity he would oversee the production of over 4,000 Liberty and Victory cargo ships during World War II, building them faster than German U-boats could sink them. He was also instrumental in the establishment of the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy at Kings Point, New York, in 1943.

Neosho was the second of what would be known as the Cimarron-class fleet replenishment oilers, which were significantly larger and much faster than previous U.S. Navy oilers. Of the 12 original Cimarron-class oilers, four were completed in 1942 as escort carriers. Three, including Neosho, were directly commissioned into the U.S. Navy. The others were purchased by the Navy in late 1940 following brief commercial service. Including later “jumboized” versions, 35 Cimarron and subtype fleet replenishment oilers were built during World War II. (Mississinewa [AO-59] would be sunk by a Japanese Kaiten manned suicide torpedo at Ulithi Atoll on 20 November 1944.) Some of these oilers would serve until the early 1990s.

Neosho was commissioned as AO-23 on 7 August 1939. The oiler immediately began fitting out with the capability for conducting alongside underway replenishment. This was still a relatively unproven concept, particularly for battleships and aircraft carriers. When Lieutenant Commander Chester Nimitz was the executive officer of Maumee (AO-2) in 1916, he devised a way to refuel destroyers underway, and this method was used with destroyers transiting the Atlantic to Europe during World War I. Nevertheless, during the interwar period it was generally considered to be too dangerous for a tanker to go alongside a capital ship when both were making way. When Nimitz became chief of the Bureau of Navigation in 1939, he instituted a series of experiments conducting alongside underway replenishment of large ships that proved it could be done safely, a capability that would be one of the most important innovations enabling the U.S. Navy to conduct combat operations for long periods far from any base.

Neosho’s conversion to a fleet replenishment oiler was complete on 7 July 1941. The ship spent the following months making multiple runs from the West Coast to Pearl Harbor carrying high-octane aviation fuel.

Neosho was 553 feet in length (almost as long as a prewar U.S. battleship) and 75 feet in width. The oiler displaced 7,590 tons empty and 25,230 tons full load. Neosho could carry 550,000 barrels of oil in 26 strongly compartmented tanks, which allowed the ship to transport different types of fuel at the same time. Two geared steam turbines and two shafts could propel the ship at 18–20 knots. Neosho’s designed complement was 304 officers and enlisted crew members. Armament on Cimarron-class oilers varied and also changed over time (and sources conflict). At the time of Pearl Harbor, Neosho appeared to have one 5-inch, 51-caliber gun on the stern, three 3-inch, 23-caliber guns for antiaircraft defense, and a number of .50-caliber machine guns. After Pearl Harbor, the antiaircraft defenses were augmented with eight 20-milimeter Oerlikon cannons, and the 5-inch gun may have been upgraded to a .38-caliber dual-purpose gun. Although the 20-milimeter cannons were a significant improvement, they still lacked the range and punch to bring down Japanese dive bombers and torpedo bombers before the weapons-release point (they were good at keeping planes from coming back a second time).

After Pearl Harbor, Neosho was a critical strategic asset, as tankers were in short supply. This situation was aggravated when the older (and smaller and slower) Neches (AO-5) was torpedoed and sunk by Japanese submarine I-72 on 23 January 1942 near Hawaii, with the loss of 57 men (126 were rescued). On 1 March 1942, tanker Pecos (AO-6) was sunk by Japanese carrier dive bombers south of Java with heavy loss of life, including most of the crew of seaplane tender Langley (AV-3) (see H-Gram 069). Neosho frequently operated independently due to a shortage of escorts (which cost the Neches) and sometimes supported carrier task forces. In late April 1942, Neosho was assigned to provide support to Task Force 17 (TF-17), centered on Yorktown (CV-5).

Battle of the Coral Sea

On 4 May 1942, aircraft from Yorktown attacked the Japanese seaplane base at Tulagi. The Japanese had just established this base across the sound north of Guadalcanal (a name which at the time meant nothing to anyone in the United States or Japan). Although the results of the raid were exaggerated, five of the big Kawanishi H6K Type 97 “Mavis” four-engine flying boats were destroyed, significantly degrading Japanese long-range search capability in the Coral Sea at a critical time. The raid also alerted the Japanese that there was at least one U.S. aircraft carrier operating in the Coral Sea, and that their planned operation to seize Port Moresby (Operation Mo) on the southeast coast of New Guinea would be opposed.

Based on intelligence reporting from decrypted Japanese communications and traffic analysis, the United States had a good understanding of the intent of the Japanese Operation Mo and of the Japanese forces involved. A U.S. carrier force, consisting of Yorktown and Lexington (CV-2), under the command of Rear Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher, was specifically committed, based on the intelligence, to oppose the Japanese Port Moresby operation and hopefully ambush the two Japanese fleet carriers Shokaku and Zuikaku (both veterans of the attack on Pearl Harbor). After launching the Doolittle Raid on Japan, carriers Enterprise (CV-6) and Hornet (CV-8) were racing toward the Coral Sea but would not make it in time (see H-Gram 004).

The Japanese plan called for transports with army troops to round the eastern tip of New Guinea to assault Port Moresby. This force was to be covered by the light carrier Shoho, four heavy cruisers, and other light cruisers and destroyers. Acting in support of the operation were the two carriers of Japanese Carrier Division 5 (CarDiv-5), the Shokaku and Zuikaku. Rear Admiral Takeo Takagi was in command of the overall carrier force, and Rear Admiral Chuichi “King Kong” Hara was in command of CarDiv-5. As Takagi did not have much aviation experience, he deferred most carrier operation decisions to Hara. (Fletcher did much the same with Rear Admiral Aubrey Fitch, who was embarked on Lexington.)

The Japanese carrier force entered the Coral Sea via a circuitous path to the north and then the east, essentially coming in south from where the United States was expecting them. Neither force wanted to use carrier aircraft to search for the other, so as not to give away their presence, relying instead on land-based aircraft to do the searching. This approach proved fruitless on 5 and 6 May, as neither side found the other.

On 6 May, Neosho refueled Yorktown and heavy cruiser Astoria (CA-34). As Neosho was alongside Yorktown, a pilot from Scouting Squadron 5 (VS-5), Lieutenant Stanley “Swede” Vejtasa, was literally strapped into the bosun’s chair (and his seabag was already across) to be sent to Neosho for onward transport to Pearl Harbor to execute change of station orders. At the last moment, the commanding officer of VS-5 managed to have Vejtasa’s orders postponed (in anticipation of battle), so Vejtasa and another VS-5 pilot remained on board Yorktown while five other sailors from Yorktown and heavy cruiser Portland (CA-33) made the chair ride to Neosho.

Vejtasa would bomb the Japanese light carrier Shoho on 7 May and would be credited with shooting down three Japanese fighters while flying a Douglas SBD Dauntless dive bomber. He subsequently transferred to flying Grumman F4F Wildcat fighters in Fighter Squadron 10 (VF-10). During the Battle of Santa Cruz in October 1942, Vejtasa was credited with shooting down seven Japanese aircraft in a single mission (actually it was four, but still…). He would be awarded the Navy Cross three times during the war, with a total of 10.25 kills credited. In another minute on 6 May 1942, his fate might have turned out quite different.

Upon completion of the refueling evolution, Neosho was directed to a position further to the south that would be presumably safer, as a major battle was expected in the next day. The destroyer Sims (DD-409) was assigned to escort Neosho, probably because unreliable boilers made the destroyer a potential liability in a major action. The commanding officer of Sims since 6 October 1941 was Lieutenant Commander Wilford Milton Hyman (USNA ’24).

Sims was the lead ship of a class of 12, the last class of destroyers completed before the outbreak of World War II (and in common with many lead ships, Sims had some significant teething problems, particularly unreliable boiler tubes prone to breaking down at inopportune times). Five Sims-class destroyers would be lost during the war. Sims was laid down on 15 July 1937 and launched on 8 April 1939, sponsored by Anne Sims, widow of the ship’s namesake (Rear Admiral William S. Sims died in 1936; during World War I he was temporarily promoted to vice admiral as commander of U.S. Naval Forces Operating in European Waters, but reverted to two-star rank after the war as president of the U.S. Naval War College).

Sims was 348 feet long and displaced 1,600 tons (standard) and 2,246 tons (full). A propulsion plant of high-pressure superheated boilers, geared turbines, and twin screws allowed the destroyer to achieve 35 knots. The ship’s designed complement was 10 officers and 182 enlisted crew members. Sims was armed with five 5-inch, 38-caliber guns in single mounts (three in turrets and two open mounts), four quadruple 21-inch torpedo tube mounts, and two depth charge racks on the stern. The destroyer’s initial antiaircraft fit of eight .50-caliber machine guns was upgraded by the time of Coral Sea with four 20-milimeter Oerlikon cannons.

After commissioning, Sims served as part of the U.S. Neutrality Patrol (see H-Gram 001), an undeclared shooting war with German U-boats. At the time of the attack on Pearl Harbor Sims was assigned to Task Force 17, centered on carrier Yorktown (which had been taken from the Pacific to augment capability in the Atlantic in anticipation of war with Germany). On 16 December 1941, Yorktown and a screen departed Norfolk to return to the Pacific. TF-17 then covered a convoy transporting U.S. Marines from San Diego to Samoa in late January.

Sims screened Yorktown during the carrier raids on the Marshall Islands; before the raids, Sims was attacked by a Japanese land-based bomber on 28 January 1942, but the four bombs impacted 1,500 yards astern. On 16 February, Sims sortied with Yorktown from Pearl Harbor to strike Wake Island (which had fallen to the Japanese at Christmas), but TF-17 was ordered south to Canton Island. Sims then screened Yorktown during the 10 March raid by Yorktown and Lexington aircraft on the Japanese landings at Lae and Salamaua, New Guinea, which caught the Japanese by surprise and inflicted significant damage.

On 7 May, the U.S. and Japanese carrier forces were actually in close proximity, but wound up each launching major air strikes in the opposite direction. Fletcher received reports of Japanese carriers off the eastern tip of New Guinea and launched a full strike from both Lexington and Yorktown, leaving only enough aircraft behind for combat air patrol to defend the carriers. The report turned out to be a garble of “cruisers,” but it was too late to recall the strike (something not easily done anyway), and the aircraft found and pummeled Shoho under an avalanche of bombs and torpedoes, sinking the light carrier with gross overkill. Shoho’s four escorting heavy cruisers went unscathed, and would form the majority of the force that inflicted the greatest defeat of the U.S. Navy at sea in the Battle of Savo Island in August 1942.

With both U.S. carrier air groups fully committed to a strike on a small carrier (Shoho), the U.S. carriers were potentially very vulnerable to a large Japanese air strike. However, Takagi and Hara had made a similar mistake, and the large Japanese air strike was heading in the wrong direction.

By the morning of 7 May, Rear Admiral Takagi was fed up with the lack of results from land-based searches, and Hara ordered the launch of carrier aircraft to search. Not knowing the U.S. carriers were actually west northwest of them, the search aircraft concentrated to the south, where the Japanese expected the U.S. carriers to be. The planes were launched just before dawn, and when the sun came up, the skies were mostly clear and the seas moderate, but growing rougher.

At 0722, lookouts on Neosho and Sims sighted two unidentified aircraft on the horizon. Neither aircraft approached close enough to be identified as enemy or friendly. The aircraft were in fact two B5N2 “Kate” torpedo bombers off Shokaku. The Japanese pilots had expected to find an aircraft carrier, and that’s what they saw, radioing back that they had sighted both an aircraft carrier and a cruiser.

Based on the contact report, the Japanese wasted no time launching a 78-plane strike, consisting of 18 Mitsubishi A6M “Zeke” fighters (more commonly known as “Zeroes”), 36 Aichi D3A “Val” dive bombers, and 24 B5N2 “Kate” torpedo bombers (the Japanese had a shortage of torpedoes, so some of the Kates were armed with bombs instead). This amounted to about 75 percent of the 108 operational aircraft on board the two carriers (diverging from Japanese doctrine, which was to launch 50 percent from both carriers and hold the other 50 percent in reserve for additional targets). The strike was led by the commander of the Shokaku air group, Lieutenant Commander Kakuichi Takahashi.

Later that morning at 0929, a bomb exploded close aboard Sims from an aircraft that had not been detected on radar nor sighted by lookouts. The detonation threw Lieutenant Commander Hyman to the deck, and he sustained a possible concussion. This plane was another Japanese carrier aircraft out searching, reporting back that it had seen no carrier or cruiser before it decided to drop a bomb on the destroyer. The plane continued to circle for a time out of gun range.

At 1005, Sims’s radar and lookouts detected between 10 and 15 aircraft coming in from 025°T (True bearing). This was Takahashi leading his strike. Sims opened fire. Disconcertingly, many of Sims’s shells were duds, as had been the case at Pearl Harbor. Takahashi carefully kept his group out of range as he quickly determined that Neosho and Sims were not an aircraft carrier and a cruiser. A large group of aircraft passed to the west of Neosho and Sims and another to the east, remaining out of range. A few planes continued to circle as the rest fanned out in a search pattern to find the carrier. For over 90 minutes, the Japanese carrier planes searched and found nothing.

At 1033, a group of about 10 planes approached Neosho from the southwest, three of which were identified as twin-engine aircraft, which dropped three bombs each from an altitude above effective antiaircraft range. Captain Phillips (temporary promotion as of 27 February) deftly maneuvered Neosho to avoid the bombs, with the closest missing 25 yards to starboard. Since twin-engine aircraft would not have come from a carrier, these were presumably Japanese land-based bombers from Rabaul at maximum range, or U.S. or Australian aircraft from Australia in a friendly fire incident no one ever owned up to (U.S. Martin B-26 Marauder twin-engine bombers did attack an Allied cruiser-destroyer force, but that was closer to New Guinea). Anyway, the origin of these planes is a bit of a mystery, at least to me.

Neosho sent a message reporting an attack by three aircraft with no hit. This message was the first that made Rear Admiral Fletcher aware of the threat to Neosho. It did not cause undue concern, as it appeared the attack had been unsuccessful and Neosho was OK. It would, however, be the last message received from Neosho for many hours.

Finally, Takahashi was convinced that the carrier was a phantom and reported back that they could find only the oiler and destroyer. “King Kong” Hara lived up to his nickname in his reaction. By that time, the two pilots who had made the original sighting report had recovered aboard and admitted they were not absolutely certain they’d seen a carrier. Other scout aircraft had not seen any carrier either. Worse, the Japanese began receiving reports of the U.S. carrier aircraft strike on Shoho. Takagi and Hara then realized they were in an extremely vulnerable position, not knowing the U.S. carriers were equally vulnerable. By this time, it was not possible to redirect the strike toward the U.S. carriers, so Hara issued a recall order.

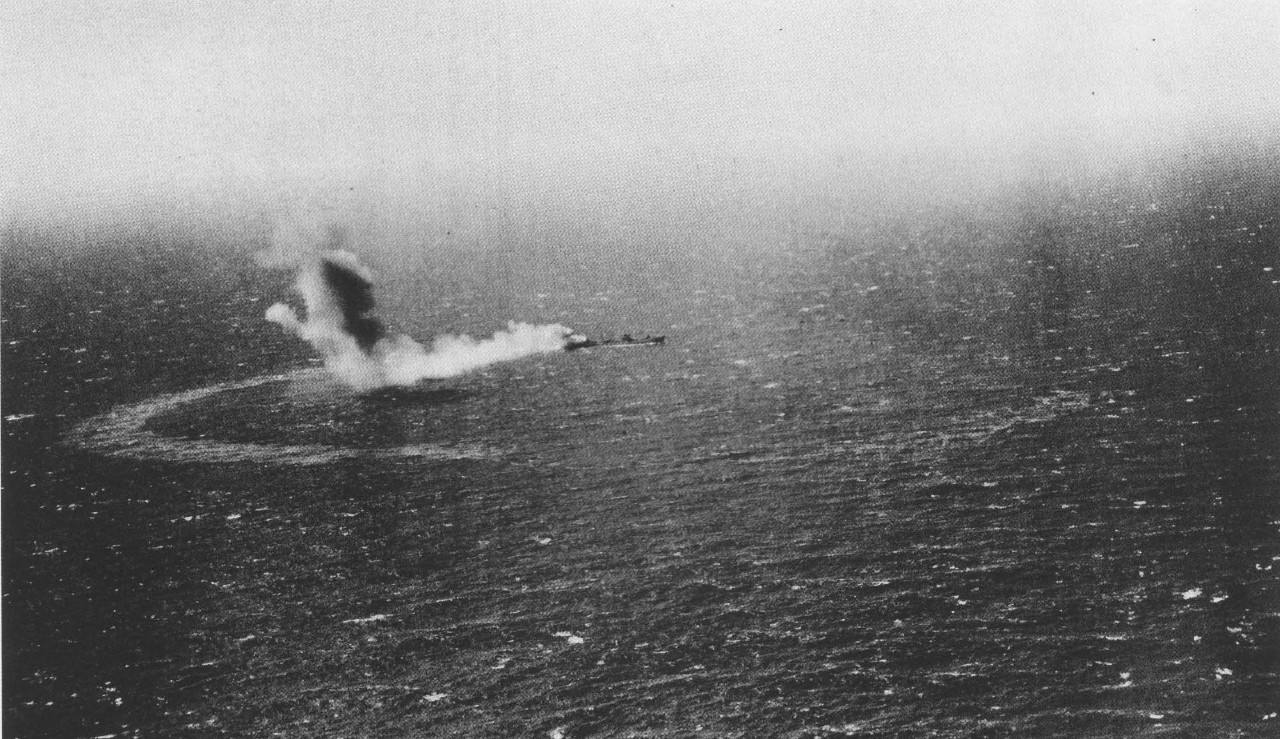

Since there was no sense in wasting precious torpedoes on an oiler, Takahashi immediately sent the torpedo bombers back, but requested permission from Hara to bomb the U.S. ships, since they were there anyway. Hara assented. Commencing at 1201 until 1218, hell rained down on Neosho and Sims from at least 24 Japanese dive bombers. Ten other planes, presumably Kates armed with bombs, dropped on Sims with only one hitting close enough to do some minor damage.

Three waves of dive bombers attacked Neosho. The first wave approached from the stern, apparently disconcerted by the maneuverability of Neosho (twin screw) and volume of antiaircraft fire, which although not very accurate was intense. All the bombs missed Neosho. One plane was hit and crashed in pieces into the ocean. The second wave had the same result except for one damaging near miss.

During the fray, four dive bombers peeled away from Neosho and attacked Sims with devastating results. The first bomb was either a hit or a very close near miss. The second bomb exploded in the forward engineering space. The third went through the upper deckhouse and exploded in the after engineering space. The fourth bomb appeared to hit near the number 4 gun toward the stern.

Sims continued to fire while being hit and struck a Japanese plane. With about half a wing and part of his tail blown off, the pilot was somehow able to hold the plane in the air long enough to crash into Neosho near the number 4 gun enclosure, starting a large fire on the oiler. The luck of both ships had run out.

Sims’s hull buckled amidships, and very quickly the midsection of the ship was awash. Sims went dead in the water, all power lost, although the auxiliary generator kicked in as it was supposed to. The radar mast collapsed. Fires were raging aft, threatening the ammunition magazine. The aft guns ceased firing although the two forward 5-inch guns continued to blast away in local control. A number of the crew had been blown overboard. Most of the ship’s rafts were destroyed.

Sims was doomed, but Lieutenant Commander Hyman was not ready to give up the ship, nor was most of his crew. Fire and damage control parties were quickly formed; however, there was no way to get from the forward to the aft end of the ship due to the flooding and fire. Two motorized whaleboats were put in the water. One immediately sank. The other drifted away from the ship in sinking condition. Sailors were able to swim to the whaleboat, start the motor, patch an 18-inch hole, and bring the boat back close to the ship. Lieutenant Commander Hyman directed the whaleboat to proceed aft and organize an attempt to flood the after magazine before the fire caused it to blow up. It quickly became apparent that this was a hopeless task as the ship was going down too fast. By this time Lieutenant Commander Hyman had ordered the bridge abandoned except for himself and a yeoman.

As Sims broke in two, Lieutenant Commander Hyman gave the order to abandon ship, arguably too late. Hyman was last seen remaining on the bridge as the ship went under. The gunners in the forward turrets didn’t get the word and were still shooting as the forward section went down. A last shell was seen to break the surface of the water from a gun already under the surface. According to the senior survivor of Sims, Chief Signalman Robert J. Dicken, the commanding officer “showed an example of courage throughout the entire engagement.” Lieutenant Commander Hyman would later be awarded a posthumous Navy Cross.

After Sims sank, there were a series of underwater explosions, one very powerful. Only one person that was still in the water was known to have survived, but was badly wounded from the effects of the shock wave through the water. After the explosions, the only survivors were 15 men in the whaleboat and about 20 on a raft, out of 252 aboard. The 20 men on the raft would never be seen again.

Unlike the first two waves, the third (and last) wave of dive bombers split up and attacked from multiple directions simultaneously, diluting the effectiveness of the antiaircraft guns. A number of gunners had already been killed by shrapnel from the near miss and the crash of the Japanese plane into Neosho. Although other crew members quickly stepped in despite the gore, the effectiveness waned at a critical point. Captain Phillips would report that three Japanese planes were shot down over the course of the attack, and another four badly damaged. But the third wave was too overwhelming.

Neosho was hit by seven bombs from the third wave. The first bomb hit the main deck on the port side. The second hit the stack deck and penetrated into the bunker tank, starting another fire. A near miss cut down a gun crew with shrapnel, decapitating one sailor (a sight burned into the memory of most of the surviving crew). A third bomb also hit the port side. The fourth bomb penetrated into the fireroom, setting off a steam leak that instantly killed every man in the space (but luckily the boilers did not blow up). Three other bombs blew large holes in fuel tanks, but passed right out the bottom of the ship without causing fires.

At this point, Captain Phillips gave the order to “make preparations for abandoning ship and stand by.” Much of the crew mistakenly processed Phillips’s direction as an order to abandon their ship. They had seen Sims go down in a matter of a couple minutes, and their own ship was obviously grievously damaged. Many of the crew panicked, and many more honestly believed they were carrying out an order to abandon the ship. Much to Captain Phillips’s consternation, all of a sudden rafts, boats, and men (including at least four officers) were going over the side and into the water (this included the officer of the deck, who abandoned his position on the bridge and jumped overboard).

By 1218, the Japanese attack was over. Sims was gone and Neosho was burning and listing, dead in the water, but did not appear to be in imminent danger of sinking (at least to the skipper, not so to just about everyone else). At 1230, Captain Phillips hailed the two whaleboats that had been lowered into the water and cast off. Two officers that had gone overboard had finally assumed leadership of the boats. Captain Phillips ordered them to retrieve men from the water and bring them back to the ship. Instead, the two boats spent the next hours in the increasingly rough seas, plucking men from the water and delivering them to seven rafts, as there were far too many men in the water to be brought aboard the whaleboats. During this time, a pharmacist’s mate from Neosho, Henry Tucker, swam from raft to raft administering aid, particularly treatment for burns, to the many wounded. At some point, however, Tucker must have tired and drowned.

In the late afternoon, the two boats returned to Neosho full of survivors, including the most badly wounded from the rafts. However, neither boat towed any rafts to Neosho. The whaleboat with 15 survivors from Sims also reached Neosho. About this time, Captain Phillips also learned that the communications officer had been so paralyzed by fear that he had sent no messages, despite orders to do so. Finally, a message went out at 1600 reporting the loss of Sims and the dire situation aboard Neosho.

As light began to fade in the afternoon, Captain Phillips made the decision that it was too late to send the boats back out to retrieve rafts before darkness set in. This was a fateful decision. Phillips assumed that a rescue ship would come quickly (this was a correct assumption); however, what Phillips did not know was that the Neosho navigator’s celestial fix, included in the 1600 report, was off by 64 miles. By the next morning, the rafts had drifted out of sight.

Upon receipt of Neosho’s distress message (sent in the clear because codebooks and sensitive material had already been deep-sixed when it appeared the ship was most in danger of sinking), the destroyer Monaghan (DD-354) from Lexington’s screen was dispatched to proceed to Neosho’s reported position. (This would also give Lexington one less escort during the next day’s climactic battle, in which Lexington would be lost.) Monaghan had already been sent south of the task force to transmit important messages (including the sinking of Shoho) so as not to compromise the carriers’ position.

As darkness fell, there was no guarantee that Neosho would remain afloat overnight, so Captain Phillips made the decision to keep and treat the wounded in the whaleboats alongside, which would give them a better chance of survival in case Neosho suddenly went down.

At the evening muster on Neosho, out of a crew of 20 officers and 267 enlisted men, 16 officers and 91 enlisted men were on board Neosho or in the whaleboats alongside. One officer and 19 enlisted men were confirmed dead. Four officers and 156 enlisted men were either dead in compartments below, drowned in the sea, or on the rafts. (It would turn out that the muster was off by two; there were actually a total of 158 missing.) There were also 15 survivors from Sims. During the night, one wounded sailor from Sims died as did one from Neosho. Neosho’s medical officer was dead or missing, but two petty officers made heroic efforts to tend the wounded. The dead sailors were committed to the deep with a short ceremony.

By the morning of 8 May, the condition of Neosho had continued to deteriorate; a list that had reached 30 degrees was partially compensated for by counterflooding and the fires had been put out, but there were signs of severe hull stress and buckling of the deck plates. The ship had minimal auxiliary power, which limited the range of the radios.

In the meantime, Monaghan was searching in the wrong place, eventually reporting there was no trace of Neosho—no debris, no oil, nothing. As the main event of the Battle of the Coral Sea unfolded, Monaghan was ordered to continue to Noumea with important messages. The destroyer Henley (DD-391), then at Noumea, received orders to get underway and search for Neosho, a risky proposition for a lone destroyer in the middle of one of the biggest battles of the war. Henley was commanded by Commander Robert Hall Smith, with the commander of Destroyer Division 7, Commander Leonard B. Austin, embarked. The search would be complicated because Neosho could neither effectively send nor receive messages (and since most received messages would have been encrypted, they would have also been unintelligible).

On 8 May, with no sign of a rescue ship, Captain Phillips decided to personally replot the navigator’s fix, and to his great distress, he discovered the math error. Given drift, Neosho was probably over 75 miles from where any ship or aircraft would be searching. Phillips shared this information with his senior officers, but not with the crew.

During the night of 8–9 May, three more wounded Neosho sailors died. Neosho still remained afloat, but for how long was anybody’s guess. A number of crew members made harrowing trips down into the ship to retrieve rations, water, and other supplies. Extensive work went into freeing another motor launch that was inaccessible due to the list. After much hard manual labor, the boat was put into the water. Several rafts were also fashioned from salvaged material on the ship.

During the night of 9–10 May, two more wounded Neosho sailors died. By the morning of 10 May, the list had by itself been considerably reduced, although it was obvious that the reason for this was because the ship was settling dangerously lower in the water. Also, unbeknownst to Captain Phillips but known to Commander Austin and Commander Hall on Henley, the Japanese carrier force had returned to the scene of the 8 May battle in the hopes of finishing off any U.S. ships (after Takagi and Hara had been royally reamed for disengaging after the severe damage to Shokaku in the 8 May battle).

By 10 May, Captain Phillips was convinced that Neosho would not remain afloat much longer, and that when the oiler did sink, it could happen very fast. He ordered that the three whaleboats and the motor launch be rigged with sails and provisioned for an extended period at sea (no one, including Captain Phillips, was very keen on this because the coast of Australia was over 500 miles away, plus the boats would be a lot harder for any searchers to find). By this time, the suffering of the crew from the heat and sunburn was intense, as no one dared go below. Everything was set in place for the crew to get in the boats (and in towed makeshift rafts) in a hurry if the ship started to go down during the night. The plan was set for the next day; the officers in charge of each boat would embark at 1200, with all crew members and provisions aboard by 1400, at which time the boats would set sail for Australia.

There was finally hope when at 1230 on 10 May an Australian Lockheed Hudson twin-engine bomber at its maximum range overflew Neosho at an altitude that there was no doubt Neosho had been seen. However, the plane could not linger. The plane did report the contact upon its return to Australia, but the message took a rather torturous and time-consuming path through General Douglas MacArthur’s headquarters into Navy channels. Fortunately, no more crew members died during the night of 10–11 May.

Early on 11 May, Henley commenced searching at Neosho’s last incorrectly reported position. Commander Austin and Commander Smith rather quickly deduced that the position report had to be incorrect (a sunken oiler should leave a big oil slick) and that if Neosho was still afloat, the oiler was probably drifting to the west northwest, a correct assumption. Henley was already heading in the right direction when the Australian position report finally arrived. Henley cranked up its speed, at great risk, given the Japanese carrier force in the Coral Sea and the possibility of submarines (although there weren’t any of those). At 0930, Henley found the oil slick.

At 1130, a U.S. Consolidated PBY Catalina flying boat overflew Henley. Henley signaled for the PBY to search to the west northwest. The PBY quickly found Neosho still afloat, wagged its wings to assure the survivors that they had been seen, and flew back to Henley to signal the location and that there were at least 50 survivors. The PBY then headed away so as to not draw any Japanese attention to the rescue operation.

At 1323, Captain Phillips logged sighting Henley. Commander Austin had no desire to hang around long, and the rescue was expedited because the whaleboats and launch were ready to go. The first boat of survivors reached Henley at 1345 and the last at 1415. Henley brought on board a total of 123 survivors—104 of Neosho’s crew, plus the five passengers from Yorktown and Portland (who all lived) and 14 survivors from Sims. Six of Neosho’s crew and one crew member from Sims had died while awaiting rescue. Two more Neosho sailors and one more from Sims would succumb to their wounds while aboard Henley. One of the Neosho crew members who died on Henley was Chief Watertender Oscar Peterson, who would be awarded a posthumous Medal of Honor for his actions in closing bulkhead steam valves during the attack, knowing that he would be severely burned in doing so.

After the survivors were on board Henley, the boats were then scuttled, although one stubbornly refused to sink (and would be seen several days later). Captain Phillips and Commander Austin conferred on what to do with Neosho. Phillips requested that the oiler be scuttled and Austin agreed. At 1428, Henley fired a torpedo at Neosho; it hit, but it was a dud. Henley fired a second torpedo that hit and exploded without any sign that Neosho was going to sink any faster. Finally, after 146 rounds of 5-inch ammunition, Neosho went under at 1522 on 11 May 1942.

Captain Phillips informed Commander Austin of the large number of men on the missing rafts and requested that the search continue. Despite the risk, Commander Austin agreed, and for three days Henley searched without any sign of the rafts or men. Henley broke off the search due to fuel state, but Commander Austin ordered another Destroyer Division 7 (DesDiv-7) destroyer, Helm (DD-388), to continue the search, despite the low probability of anyone on the rafts surviving for so long.

After daybreak on 16 May, lookouts on Helm sighted what appeared to be a man standing up in a raft. Helm then found a raft with four survivors of Neosho, all in very bad shape. Seaman Second Class William A. Smith had seen the ship, and with what had to have been a superhuman effort given his weakened and dehydrated condition, managed to stand up. Had he not done so, in all likelihood he would not have been seen in the grey-painted low-riding water-logged raft.

The four survivors were the last of what had been 68 men in four rafts lashed together. In a nightmarish nine days, the others had succumbed to wounds, exposure, dehydration, and worst of all, salt water ingestion. In the week prior to the sinking, rain squalls were common. In the week afterward, there was no rain at all. Against all warnings, desperately thirsty sailors would drink salt water, resulting in violent hallucinations followed by an excruciating death. Dead bodies that were rolled off the raft would float alongside it for hours, devoured by all manner of sea life, adding to the horror. Whatever happened to the other three rafts is unknown, other than that no one aboard them was ever found.

Helm resumed searching for other rafts, but one of the survivors, Seaman Second Class Ken Bright, died. The commanding officer determined that the others would die too if they didn’t get medical care ashore, so Helm broke off the search. Another of the raft survivors, Seaman Second Class Thaddeus Tunnel, died in the hospital in Brisbane, Australia. Thus, of 158 missing men from Neosho, only William Smith and Seaman Second Class Jack Rolston survived the horrific ordeal.

On 25 May, Captain Phillips submitted an extensive after-action report, which included several recommendations, including that life rafts should be a bright color (covered by tarpaulin on the ship) rather than hard-to-see gray. In addition, life rafts should be equipped with a telescoping stick to permit a flag to be bent at the top, thus aiding the raft’s visibility. He recommended that all ship’s boats be equipped for sail. His last recommendation was “that the words ‘ABANDON SHIP’ be deleted from all preliminary orders given; that the preliminary order be ‘FALL IN AT (or MAN) BOAT AND RAFT STATIONS,’ and that the words ‘ABANDON SHIP’ be used only when it is desired to accomplish just that, namely, for all personnel to leave the ship.”

Captain Phillips also recommended nine members of his crew receive awards of the highest order (Phillips didn’t know about Pharmacist’s Mate Tucker’s heroism when he wrote the report). He also recommended 32 personnel (including at least one from Sims) for accelerated advancement and promotion.

Chief Watertender Oscar Verner Peterson was awarded a posthumous Medal of Honor:

For extraordinary courage and conspicuous heroism above and beyond the call of duty while in charge of a repair party during an attack on the U.S.S. NEOSHO by enemy Japanese aerial forces on 7 May 1942. Lacking assistance because of injuries to the other members of his repair party and severely wounded himself, Peterson, with no concern for his own life, closed the bulkhead stop valves and in so doing received additional burns which resulted in his death. His spirit of self-sacrifice and loyalty, characteristic of a fine seaman, was in keeping with the highest traditions of the U.S. Naval Service. He gallantly gave his life in the service of his country.

Peterson had enlisted in the U.S. Navy in 1920 and spent his entire career at sea. He died of his burn wounds on 13 May 1942, aboard Henley, after being rescued from Neosho.

Due to an apparent administrative oversight, there was no award ceremony for Peterson’s family; rather, the medal was mailed to his widow. This was not corrected until 2010 when Rear Admiral James A. Symonds, commander, Navy Region Northwest, formally presented the Medal of Honor, a 48-star flag, and an appropriate marker to Peterson’s son and family.

The Edsall-class destroyer escort DE-152 was named in Peterson’s honor. Commissioned in September 1943, Peterson escorted numerous Atlantic convoys, hitting U-550 with gunfire and shallow-set depth charges and causing the U-boat to surrender, though it still sank. Peterson was decommissioned at the end of the war and recommissioned during the Korean War for Cold War service including the Cuban Missile Crisis naval quarantine. Peterson also appeared in the 1962 Hollywood movie PT 109 playing the part of the Japanese destroyer that rammed and sank future president John F. Kennedy’s patrol torpedo (PT) boat.

Other personnel receiving awards for valor on Neosho include the following:

Pharmacist’s Mate Third Class Henry Tucker was awarded a posthumous Navy Cross for his valor in swimming from raft to raft administering burn treatments until he disappeared. The John C. Butler-class destroyer escort DE-377 was named in his honor, but construction was cancelled in 1944. His name was then given to Gearing-class destroyer DD-875, commissioned in March 1945, earning seven battle stars in Korea and Vietnam and a Combat Action Ribbon before being transferred to the Brazilian Navy in 1973.

Lieutenant Commander Thomas M. Brown was awarded a Navy Cross for his actions as gunnery officer in shooting down three Japanese aircraft and damaging four more, as well as serving as de facto executive officer due to injuries to Lieutenant Commander Francis J. Firth.

Silver Stars were awarded to Lieutenant Commander Francis J. Firth, the executive officer, Lieutenant Louis Verbrugge, the engineering officer, Machinist’s Mate First Class Harold Bratt, and Machinist’s Mate Second Class Wayne Simmons. Pharmacist’s Mate First Class William J. Ward was awarded a Navy and Marine Corps Medal for his role in caring for the many wounded after the medical officer had been killed. Chief Pharmacist’s Mate Robert W. Hoag was also commended for his action (there was no Commendation Medal yet).

The commanding officer of Neosho was awarded a Silver Star:

The President of the United States of America takes pleasure in presenting the Silver Star to Rear Admiral (then Captain) John Spinning Phillips, United States Navy, for conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity as Commanding Officer of Fleet Oiler U.S.S. NEOSHO (AO-23), in action against enemy Japanese forces in the Battle of the Coral Sea, on 7 May 1942. Attacked by enemy dive-bombing planes attacking from all directions, Rear Admiral Phillips maneuvered his ship with skill and avoided many of the hostile bombs. When violent fires were started and his ship was seriously damaged by bomb hits and a crashing plane, he continued to fight off attacking hostile aircraft, causing the destruction of three planes and damage to four others. With the NEOSHO in sinking condition after the attack, Rear Admiral Phillips immediately assembled all survivors, insured the welfare and safety of the wounded and supervised abandoning operations. His coolness, courage and inspiring leadership throughout this battle reflect the highest credit upon Rear Admiral Phillips and the United States Naval Service.

In his report, Captain Phillips also censured three officers “whose performance of duty contributed to unnecessary confusion, made search for survivors uncertain, and detracted from what was otherwise a glorious achievement in the history of the United States Navy.” The three officers all happened to be Naval Reserve (as were most of the officers on the ship), and the comments were unvarnished. As an example, the communications officer “did not display the qualities of a leader, and did not inspire courage or confidence in those who came in contact with him … he should at least make an attempt to appear courageous even though inwardly frightened.” Despite the scathing comments, Phillips finished with this: “Inasmuch as these three officers volunteered their services for active duty long before the entry of the United States in the present war, thereby showing a laudable intention, that they all conducted themselves in a creditable manner in the face of the enemy at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, and that they, as well as other personnel on board, were subject to a terrific and continuous attack by dive bombers, with concurrent shock and numbing of faculties, the Commanding Officer feels that the best interests of the Navy will be served by not recommending them for Court Martials. Appropriate comments will be made on the fitness reports of the three officers concerned.”

Commander Phillips was offered a follow-on at-sea command more than once, but he declined each time. He nevertheless was promoted to rear admiral and served the rest of the war in intelligence assignments.

The commanding officer of Sims was awarded a posthumous Navy Cross in April 1943:

The President of the United States of America takes pride in presenting the Navy Cross (Posthumously) to Lieutenant Commander Wilford Milton Hyman, United States Navy, for extraordinary heroism and distinguished service in the line of his profession as Commanding Officer of the Destroyer U.S.S. SIMS (DD-409), during operations in the Coral Sea on 7 May 1942. Lieutenant Hyman skillfully warded off the first raid of a hostile aircraft attack on his vessel and the ship it was escorting, and, in the second raid, when the Sims lay dead and crippled in the water, he kept her guns blazing away until the last Japanese plane had disappeared. Then he coolly directed salvage and repair operations until the bridge of the vessel was completely awash and he went down into the sea. The conduct of Lieutenant Commander Hyman throughout this action reflects great credit upon himself, and was in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service. He gallantly gave his life for our country.

The Allen M. Sumner-class destroyer DD-732 was named in Hyman’s honor. Commissioned in June 1944, Hyman was hit by a kamikaze off Okinawa on 5 April 1945 with the loss of 12 men killed and 40 wounded. After undergoing repairs, Hyman served in Korea and in the Cuban Missile Crisis naval quarantine before being decommissioned in November 1969

Of the search ships, destroyer Monaghan, which sank a Japanese midget submarine inside Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941 and earned 12 battle stars, was lost in Typhoon Cobra off Luzon in December 1944 with all but six of her crew. Destroyer Henley, with four battle stars, was torpedoed and sunk by Japanese submarine RO-108 off Finschafen (near New Guinea) with the loss of 15 of her crew; 243 were rescued after a relatively short time. Helm survived the war with 11 battle stars and helped rescue 605 survivors of the escort carrier Bismarck Sea (CVE-95), sunk by a kamikaze off Iwo Jima in February 1945.

Of note, there are significant differences in eyewitness accounts of the attack on Neosho and Sims. I did my best at reconciliation but I doubt there will ever truly be a definitive account of that action. I generally stayed close to the account of the commanding officer of Neosho. The book by Don Keith (in sources below) is the best I’ve seen on the subject, besides being an excellent read.

See H-Gram 005 for a more comprehensive treatment of the battle.

(Sources include: Don Keith, The Ship that Wouldn’t Die: The Saga of the USS Neosho—a World War II Story of Courage and Survival at Sea (New York : NAL Caliber, 2016); Chief Signalman Robert J. Dicken, “Personal Observations of Sims #409 Disaster,”13 May 1942, in USS Neosho (AO-23) War Diary, 1 April 1942–7 May 1942, Record Group 38 (RG 38), National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), College Park, MD; Captain John S. Phillips, “Engagement of USS Neosho with Japanese Aircraft on May 7, 1942; Subsequent loss of USS Neosho; Search for Survivors,” 7 May 1942, , RG 38, NARA; and NHHC Dictionary of American Fighting Ships [DANFS].)