H-Gram 073: 80th Anniversary of the Guadalcanal Campaign

16 August 2022

Rear Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner, commander of Task Force 61 (left), and Major General A. A. Vandegrift, USMC, commander of the 1st Marine Division, working on the flag bridge of USS McCawley (AP-10), at the time of the Guadalcanal-Tulagi landings (Operation Watchtower), August 1942 (80-CF-112-4-63).

Download a PDF of H-Gram 073 (3.3 MB).

This H-gram provides a synopsis of the Battle of Guadalcanal, which lasted from 7 August 1942 to February 1943, and included two major carrier versus carrier battles (Eastern Solomons and Santa Cruz), five major night surface actions (Savo Island, Cape Esperance, Friday the 13th of November, Saturday the 14th of November, and Tassafaronga), multiple submarine attacks (including the sinking of USS Wasp—CV-7) and air attacks (including the Battle of Rennell Island), numerous smaller surface actions and shore bombardments (including “All Hell’s Eve”), and near-continuous air-to-air combat whenever weather permitted. U.S. and Japanese losses were extensive, and roughly even, but in the end, the United States could replace losses and the Japanese couldn’t. It was Guadalcanal, more so in many ways than Midway, that truly turned the tide of the Pacific War, at great cost: about 5,000 U.S. Navy personnel lost to all causes, plus 1,152 Marines and 446 U.S. Army personnel ashore.

Overview

Since I wrote extensively about the Battle of Guadalcanal for the 75th Anniversary in 2017, this H-gram will provide a short synopsis of each of the previous H-grams along with the respective links.

Former Secretary of Defense and retired Marine Corps general James Mattis noted that "any commander who is too busy to read will fill body bags with his troops as he learns the hard way." Note also that the Chinese study the Guadalcanal campaign as a means to understand how to persevere in warfare when two evenly matched sides are clubbing the hell out of each other.

Guadalcanal H-grams

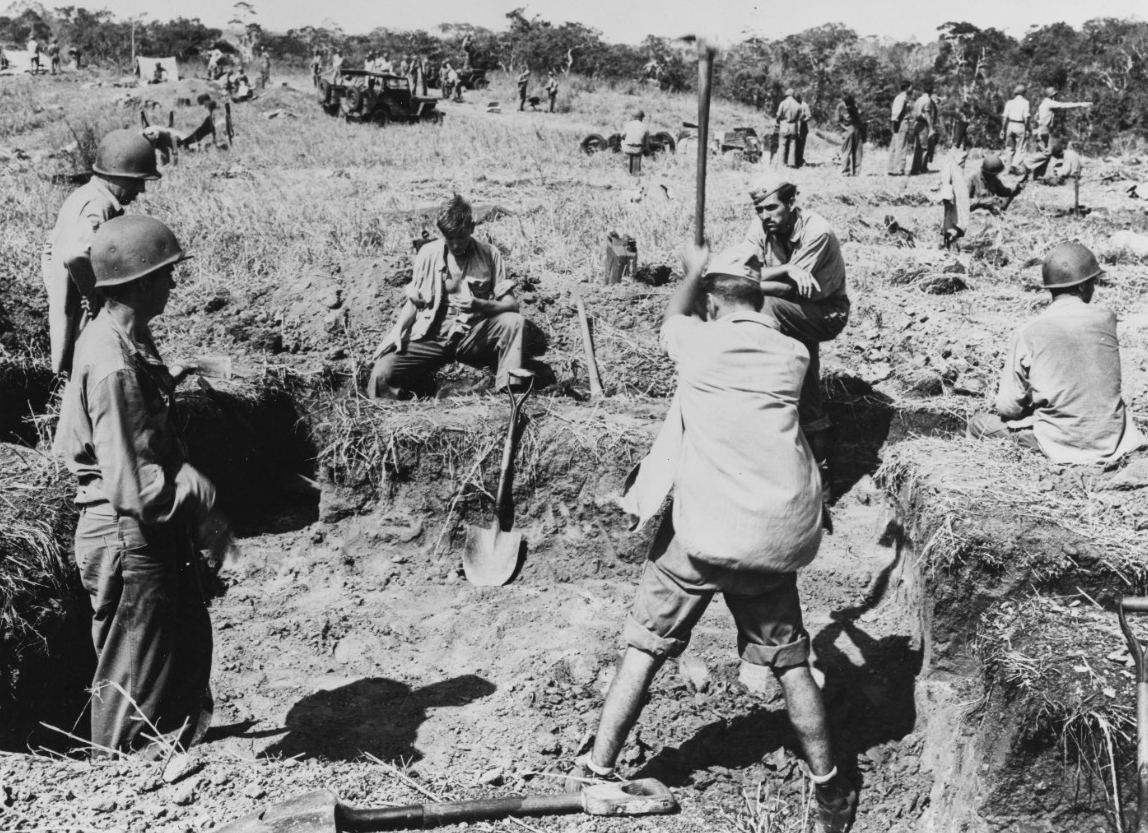

H-Gram 009 provides an overview of the Battle of Guadalcanal and the first major night surface action, the Battle of Savo Island. The U.S. Marine Corps landings on Guadalcanal on 7 August 1942 caught the Japanese completely by surprise, with minimal resistance on Guadalcanal itself and only spirited but short resistance on islands near Tulagi (across what would become known as “Ironbottom Sound”) from Guadalcanal. The Marines captured the unfinished airfield on Guadalcanal, which would be subsequently finished and named Henderson Field and then would become the objective of the fierce and bloody battles ashore, at sea, and in the air.

During the course of the Guadalcanal campaign, the U.S. would lose two aircraft carriers (Wasp and Hornet—CV-8), five U.S. (and one Australian) heavy cruisers, two light cruisers, 15 destroyers, and numerous other smaller vessels—plus extensive damage to many more ships. The U.S. Navy and Marines would lose about 400 aircraft during the course of the campaign. At sea, the Japanese navy actually lost somewhat fewer personnel than the United States—about 3,800 men—but more than 7,000 Japanese army troops would go down with sunken troop transports, and more than 20,000 would be lost on the island itself. The Imperial Japanese Navy would lose two battleships and a light carrier, plus two heavy cruisers and multiple destroyers. It was the loss of the two battleships that actually caused the Japanese navy to stop feeding ships into the meat grinder off Guadalcanal, in the end limiting their efforts to inadequate attempts by destroyers (the “Tokyo Express”) to resupply Japanese troops on the island. Ultimately, the Japanese executed one of the most successful deception operations of the war when they evacuated their last surviving troops from Guadalcanal in February 1943.

Although the U.S. landing caught the Japanese navy by surprise, it reacted swiftly with characteristic aggressiveness, first with land-based air attacks on 7 and 8 August, and then a night surface action on 8–9 August. This first naval action would be known as the Battle of Savo Island, and would be the worst defeat at sea suffered by the U.S. Navy in history. In what should have been an evenly matched battle between a Japanese force of five heavy cruisers, two light cruisers, and a destroyer against an Allied force of four U.S. heavy cruisers, one Australian heavy cruiser, and six U.S. destroyers, the Japanese achieved tactical surprise and the result was a debacle. The heavy cruisers Astoria (CA-34), Quincy (CA-39), Vincennes (CA-44), and HMAS Canberra were sunk, with only minimal damage to the Japanese (993 U.S. and 84 Australian sailors, and 58 Japanese sailors were killed). Fortunately, the Japanese commander chose not to attack into the vulnerable U.S. troop transports and supply ships that were sitting ducks still in the act of off-loading. H-Gram 009 contains an overview of the Battle of Savo Island, and attachment H-009-1 “Defeat at Savo Island” has full detail of this disaster, termed by Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Ernest J. King as “the blackest day of the war,” most of which was kept secret from the American public during the war due to wartime censorship.

Following the defeat at Savo Island, U.S. surface forces quickly vacated the waters near Guadalcanal, followed a day later by the transports. The three supporting U.S. aircraft carriers had also moved further away due to concern for air and submarine attack. It was during this period that the myth that the U.S. Navy “abandoned” the Marines of Guadalcanal took root, when in fact the Navy was running supplies into Guadalcanal at night on four fast destroyer-transports, three of which would be lost in the process, losing more men than the Marines lost in the famous Battle of Bloody Ridge (12–14 September 1942). H-Gram 010 provides an overview of the challenges of supplying the Marines on Guadalcanal (so much so that it became known to those on the island as Operation Shoestring rather than the formal name, Operation Watchtower). This includes the sacrifice of TRANSDIV 12, plus the major Japanese navy offensive push that resulted in the carrier versus carrier action known as the Battle of the Eastern Solomons, as well as actions by Japanese submarines south of Guadalcanal.

H-Gram 010’s attachment H-010-1 “Operation Shoestring” provides additional detail on the logistics issues at Guadalcanal, as well as on the valiant fight of the destroyer-transports Gregory (APD-3) and Little (APD-4) against a much superior force of Japanese destroyers; both APD skippers were lost in the battle with their ships, as was the TRANSDIV 12 commander, Hugh Hadley. (The destroyer named in honor of Hadley—DD-774—would be heavily damaged by kamikazes at Okinawa on 10 May 1945, but in the process shoot down more than 23 Japanese aircraft, the all-time record for a single ship in a single day’s engagement.)

Attachment H-010-2 “The Battle of the Eastern Solomons” provides detail on this 24 August engagement, the third major carrier battle of the war, and a narrow U.S. victory. The two surviving Japanese fleet carriers Shokaku and Zuikaku (veterans of the Battle of the Coral Sea, but that missed the Battle of Midway) and the light carrier Ryujo faced off against U.S. carriers Enterprise (CV-6) and Saratoga (CV-3), with Wasp (CV-7) missing the battle due to refueling. Ryujo was sunk by the reconstituted Torpedo Squadron EIGHT (VT-8) and Enterprise was badly damaged. The Japanese withdrew.

Attachment H-010-3 “Torpedo Junction” provides detail on the extensive Japanese submarine response to the U.S. operations around Guadalcanal. On 31 August 1942, I-26 hit Saratoga with a torpedo that put her out of action for months. On 15 September, I-19 fired what was arguably the most effective single spread of torpedoes (six) in history, hitting the carrier Wasp (CV-7), battleship North Carolina (BB-55), and destroyer O’Brien (DD-415). Wasp was sunk. North Carolina was put out of action for two months. O’Brien broke apart and sank after transiting 2,800 miles trying to get to Pearl Harbor for repair.

Attachment H-010-4 “Samuel B. Roberts” tells the story of Navy Coxswain Samuel B. Roberts, who was awarded a posthumous Navy Cross for sacrificing his life while drawing Japanese fire away from other landing craft extracting Marines who had become trapped behind Japanese lines on Guadalcanal. Three ships have been named for Roberts: The first, destroyer escort DE-413, went down off Samar, Philippines in October 1944 in one of the most valiant actions in the history of the U.S. Navy; the second, destroyer DD-823, had a distinguished Cold War, Cuban Missile Crisis, and Vietnam War record; the third, guided missile frigate FFG-58, survived a devastating strike on an Iranian moored contact mine in the Persian Gulf in April 1988.

H-Gram 011 continues the account of the Battle of Guadalcanal into September and October 1942, with an overview of the narrow U.S. victory in a night surface action known as the Battle of Cape Esperance on 11–12 October 1942 and of the second major night surface action, as well as the devastating bombardment of Henderson Field by two Japanese battleships on the night of 13–14 October, known as “All Hell’s Eve.” The overview also includes the fourth major carrier battle of the war, the Japanese Pyrrhic victory known as the Battle of Santa Cruz on 26 October 1942.

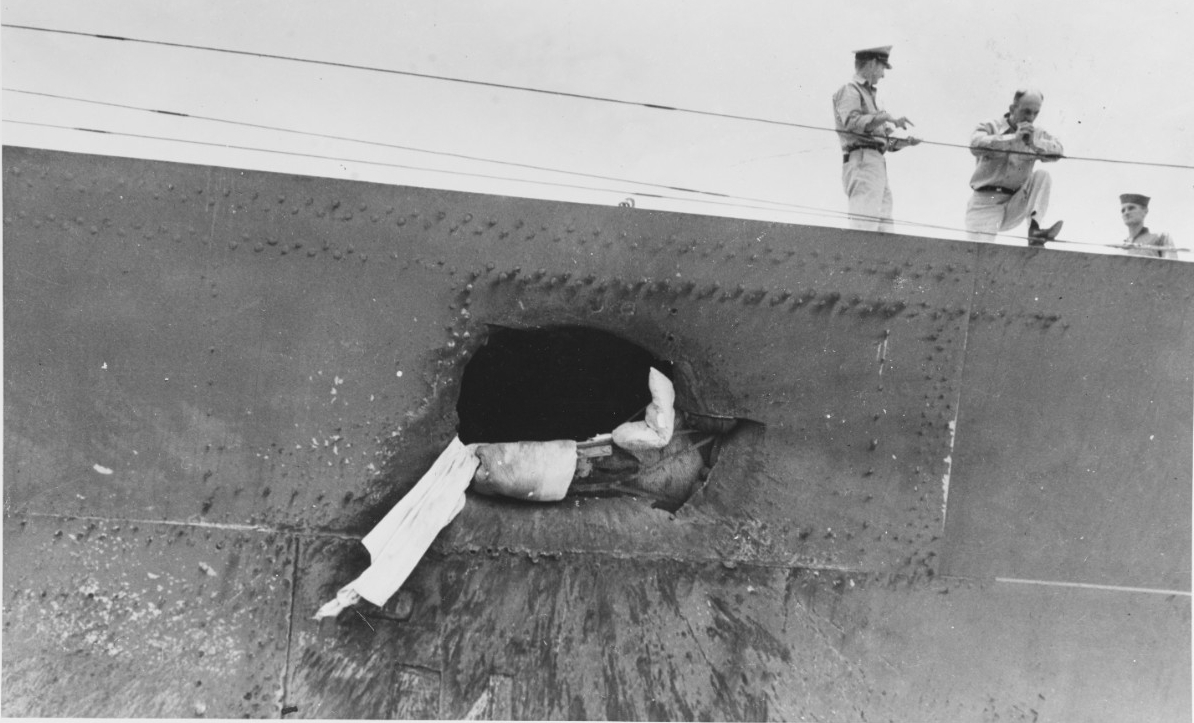

Attachment H-011-1 “Victory at Cape Esperance” provides detail on the confused Battle of Cape Esperance, where pretty much everything went wrong—but more so for the Japanese, whose commander refused to believe he was facing an American force (and not engaging in “friendly fire” with other Japanese) until it was too late. The Japanese lost a heavy cruiser and a destroyer, while the U.S. Navy lost a destroyer. Luckily, superb damage control kept the light cruiser Boise (CL-46) from being blown to smithereens by a magazine explosion, but at a cost of 107 of her crew.

The effect of the U.S. victory at Cape Esperance was short-lived, as on the night of 13–14 October, the Japanese battleships Kongo and Haruna arrived by surprise off Guadalcanal, opposed ineffectively by only four PT-boats, and proceeded to pump almost 1,000 14-inch shells into Henderson Field, destroying more than half the aircraft and damaging most of the rest, and killing 41 Marines. The psychological effect of this bombardment was profound (and recriminations between the Navy and Marine Corps echoed for decades). As this was happening, 237 U.S. Navy crewmen on the destroyer Meredith (DD-434) and fleet tug Vireo (AT-144) died when the two ships were attacked by 38 Japanese carrier aircraft while attempting to bring critical aviation fuel to Guadalcanal. Meredith was sunk and the 100 survivors drifted in shark-infested waters for three days. The story of Meredith’s valor and sacrifice is recounted in attachment H-011-2 “Forgotten Valor.”

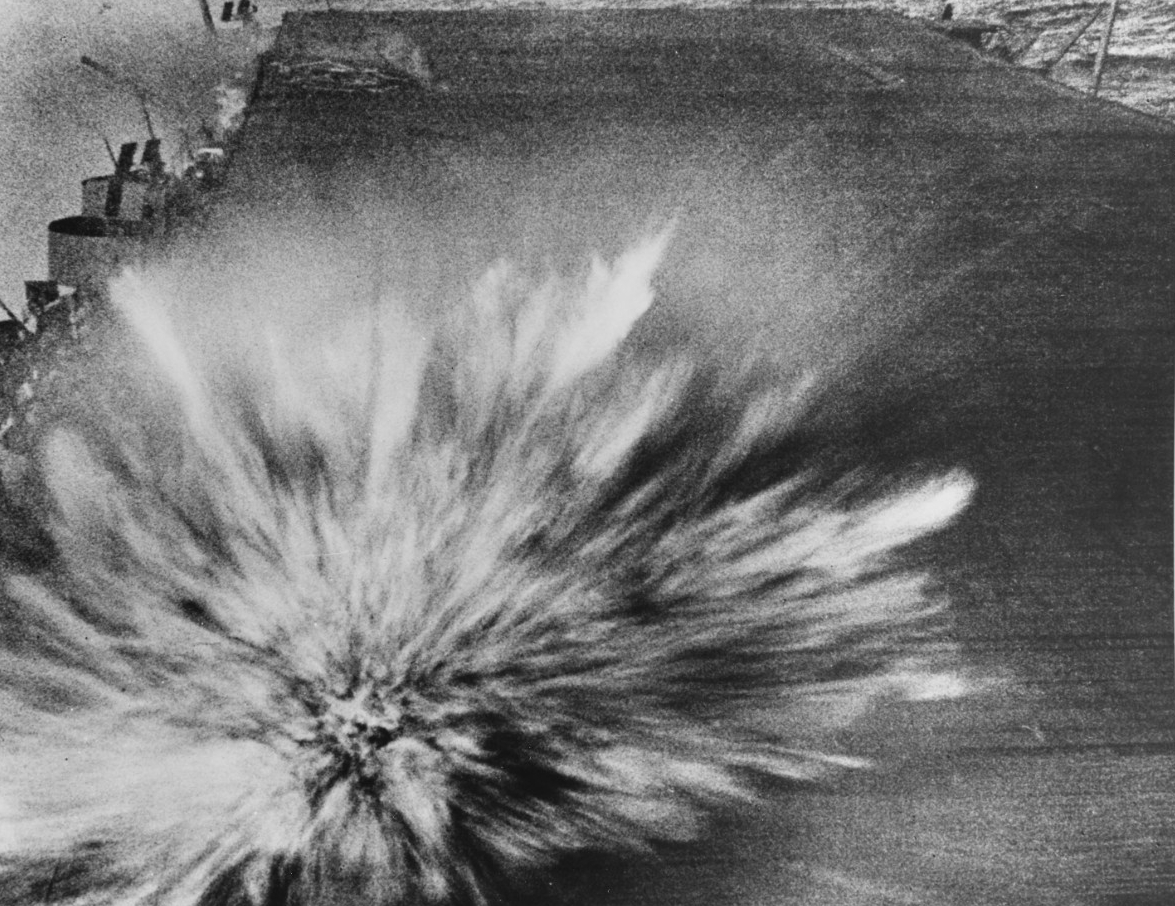

The fourth major carrier battle of the war took place after Vice Admiral Robert L. Ghormley, commander of the South Pacific Area, was relieved of command and replaced by Vice Admiral William F. Halsey, who directed a much more aggressive posture against the Japanese. In late October 1942, the Japanese mounted a major naval offensive that was supposed to be timed with a major ground attack by the Japanese army on Guadalcanal. The army offensive was fiasco, but a Japanese naval force that included four aircraft carriers (fleet carriers Shokaku and Zuikaku, medium carrier Junyo, and light carrier Zuiho) faced off against the carrier Hornet (CV-8) and Enterprise, which arrived in the nick of time after repairing damage incurred during the Battle of the Eastern Solomons. The forces engaged on 26 October near the Santa Cruz Islands northeast of Guadalcanal, trading air strikes. Zuiho was knocked out of the battle early on by a lucky hit from two U.S. scout bombers and Shokaku was badly damaged.

Boise (CL-47) arrives at the Philadelphia Navy Yard in November 1942 for repair of battle damage received during the Battle of Cape Esperance. Note the forward 6-inch/47-caliber triple gun turret trained to starboard. It was jammed in this position during the action when a Japanese 8-inch shell hit the armored barbette just below the turret (80-G-300235).

During the Battle of Santa Cruz, the Japanese executed what was probably the best coordinated dive-bomber and torpedo-plane attack of the war, leaving Enterprise damaged and Hornet crippled. Under continuing air attack, attempts to tow Hornet failed, as did attempts to scuttle her after she was abandoned, and she was left behind to be torpedoed and sunk by Japanese destroyers. With Hornet sunk and Enterprise damaged, the U.S. withdrew (leaving the Navy temporarily without any operational aircraft carriers in the Pacific). However, the cost to the Japanese for this “victory” was extremely high given the number of aircraft and aircrew lost to vastly improved U.S. shipboard anti-aircraft defenses (more than at Coral Sea, Midway, and Eastern Solomons combined). By the end of the Battle of Santa Cruz, the majority of Japan’s experienced Pearl Harbor veteran pilots had been lost; in fact, losses were so severe that the Japanese carrier force would not give battle for another two years. The details of this crucial battle are in attachment H-011-3 “Santa Cruz.”

A Japanese Type 99 shipboard bomber (Allied codename "Val") trails smoke as it dives toward Hornet (CV-8), during the morning of 26 October 1942. This plane struck the ship's stack and then her flight deck. A Type 97 shipboard attack plane ("Kate") is flying over Hornet after dropping its torpedo, and another Val is off her bow. Note anti-aircraft shell burst between Hornet and the camera, with its fragments striking the water nearby. Hornet was lost in the battle (80-G-33947).

In H-Gram 012, the battle for Guadalcanal reaches a culmination and turning point in two of the most vicious battles ever fought by the U.S. Navy: the night action between American cruisers and destroyers and Japanese battleships in the pre-dawn hours of Friday, 13 November and a battleship versus battleship action on the night of 14–15 November. Following a comparative lull as both U.S. and Japanese navies licked their wounds after the Battle of Santa Cruz, the Japanese mounted yet another major push to reinforce and retake Guadalcanal. With the carriers on both sides effectively out of action (but not the U.S. aircraft at Henderson Field), the impending battles would be primarily surface actions.

Attachment H-012-1 “The Battle of Friday the 13th” provides detail on the sea battle that occurred off Guadalcanal early on 13 November 1942, a ferocious and chaotic night melee described as “a bar room brawl after the lights were shot out,” with individual ship actions “like minnows in a bucket.” The mission of the Japanese force of battleships Hiei and Kirishima, a light cruiser, and 11 destroyers, was to administer another devastating bombardment to Henderson Field, so that a transport group with 7,000 Japanese troops could reach Guadalcanal. The mission of the hastily thrown-together U.S. force of two heavy cruisers, three light cruisers, and eight destroyers was to stop the Japanese battleships, a mission recognized by senior American officers as “suicide.” They were right.

By the time the battle was over—including the sinking of the severely damaged light cruiser Juneau (CL-52) by a submarine the next morning—1,439 American sailors were dead, including Rear Admiral Dan Callaghan, Rear Admiral Norman Scott, and Captain Cassin Young (and all five Sullivan brothers on Juneau), making this by far the most costly sea battle in U.S. Navy history. In addition to Juneau, the light cruiser Atlanta (CL-51) and four destroyers were sunk, and heavy cruisers San Francisco (CA-38) and Portland (CA-33) and two destroyers were badly damaged. The Japanese lost only two destroyers in the battle, but the battleship Hiei was crippled and could not clear the area. Most importantly, the U.S. force, at extraordinary sacrifice, prevented the battleship bombardment. Over the next days, planes from Henderson Field, augmented by planes from partially operational carrier Enterprise, sank Hiei and most of the transports, with 5,000 Japanese troops going down with the ships (and all the equipment of the 2,000 who survived). Five Navy personnel were awarded the Medal of Honor, including to Callaghan and Scott, and three (one posthumously) to men on San Francisco who fought on after more senior officers were killed.

The Japanese persisted with their objective and, on the night of 13-14 November, two Japanese heavy cruisers bombarded Henderson Field (there were no U.S. ships left to oppose them), but their 8-inch guns did far less damage than those of a battleship. With intelligence indicating a Japanese battleship force was heading back to Guadalcanal, Vice Admiral Halsey took a major gamble and committed the two new U.S. battleships Washington (BB-56) and South Dakota (BB-57) and four escorting destroyers to oppose the Japanese. The Japanese force was centered on the battleship Kirishima (which had come through the Friday the 13th battle virtually unscathed) with two heavy cruisers, two light cruisers, and nine destroyers.

The five Sullivan brothers onboard Juneau (CL-52) at the time of her commissioning ceremonies at the New York Navy Yard, 14 February 1942. All were lost with the ship following the 13 November 1942 Naval Battle of Guadalcanal. The brothers are (from left to right): Joseph, Francis, Albert, Madison, and George Sullivan. George survived Juneau's sinking on 14 November, but died in the waters off San Cristobel Island five days later (NH 52362).

The two forces engaged on the night of 14–15 November, southwest of Savo Island. The battle initially went badly for the U.S. Navy, as South Dakota suffered a major power failure at the worst moment, was hit numerous times, and was on fire and out of action. The screening destroyers absorbed the Japanese torpedo attack: Three destroyers were sunk and the fourth put out of action. Washington then fought on alone and with superb radar-directed gunnery pummeled Kirishima, which sank, while dozens of Japanese torpedoes miraculously missed. Attachment H-012-4 “The Battle of Saturday the 14th” provides detail on this action, the only one of two battleship versus battleship duels in U.S. Navy history.

On the night of 30 November–1 December, a U.S. Navy force of four heavy cruisers, one light cruiser, and six destroyers intercepted and ambushed a Japanese Tokyo Express run of eight destroyers (six encumbered by supplies). Despite the advantage of intelligence warning, radar, surprise, and overwhelming firepower, by the end of the battle, the heavy cruiser Northampton (CA-26) had been sunk, the heavy cruisers Minneapolis (CA-36), New Orleans (CA-36), and Pensacola (CA-24) had been grievously damaged, and 395 American sailors killed in what was probably the most successful surface torpedo attack in history, at a cost of one Japanese destroyer. A significant factor in the defeat was that the U.S. Navy still failed to believe that the Japanese had a torpedo that was much more powerful, much faster, and with a much longer range than our own—the Type 93 oxygen torpedo, later known as the “Long Lance.” Attachment H-013-1 “The Battle of Tassafaronga” provides detail on this embarrassing defeat. After Tassafaronga, like the Japanese, the Navy stopped sending heavy ships into the confined waters of “Ironbottom Sound” off Guadalcanal.

H-Gram 015 covers the end of the Guadalcanal campaign, specifically the Japanese Operation Ke and the Battle of Rennell Island. Despite their “victory” at Tassafaronga, the Japanese Tokyo Express that night had failed in their mission to deliver supplies to Japanese troops on Guadalcanal. Even when successful, the flow of supplies via the Tokyo Express could not sustain the Japanese troops, who were quite literally starving to death and dying of debilitating jungle diseases. However, in January 1943, all indications pointed to yet another major Japanese offensive push to get reinforcements to the island. Admiral Nimitz committed virtually the entire Pacific Fleet to countering this expected thrust, including carriers Enterprise and Saratoga, three modern battleships, and numerous cruisers, including three new Cleveland-class light cruisers. As it turned out, Operation Ke was actually a massive and well-crafted deception covering the withdrawal of the remaining 10,000 Japanese troops from Guadalcanal. They left 20,000 dead behind, along with a handful of dying cripples who mounted a surprisingly effective rear-guard delaying action. Thus, that it wasn’t until 7 February that the U.S. Army forces (who had relieved the Marines) realized the Japanese were gone. In addition to the Japanese dead on the island, another 10,000 were lost at sea, including about 3,800 Imperial Japanese Navy sailors during the course of the campaign since August.

Battle of Rennell Island, 29–30 January 1943: USS Chicago (CA-29), at left, under tow at five knots by USS Louisville (CA-28) on the morning of 30 January 1943. The damaged cruiser had been torpedoed by Japanese aircraft on the previous night. A tug, probably USS Navajo (AT-64), is alongside Louisville (NH 94681).

The Japanese Navy got in their last blows at Guadalcanal at the end of January 1943, one of which was known as the Battle of Rennell Island, described in detail in attachment H-015-2 “Battle of Rennell Island.” On the night of 29 January, a force of elite Japanese navy land-based bombers, specially trained for night aerial torpedo attack, hit the heavy cruiser Chicago (CA-29) with two torpedoes near Rennell Island, southwest of Guadalcanal. Despite extraordinary damage control to keep the ship afloat, a series of tactical blunders left Chicago exposed to a follow-on torpedo attack the next afternoon. Hit by four more torpedoes, Chicago the only heavy cruiser to have survived the debacle of the Battle of Savo Island, went down. On 1 February, as one more sharp stick in the eye, Japanese dive-bombers hit the destroyer De Haven (DD-469) off Guadalcanal, detonating her forward magazine and sending her to the bottom with 167 of her crew. (The last U.S. warship sunk off Guadalcanal was Aaron Ward—DD-483—a survivor of the Friday the 13th battle, by Japanese aircraft in April 1943.)

With the Battle of Rennell Island and the end of Operation Ke, the Guadalcanal campaign was effectively over. After six months of some of the most vicious combat in the history of naval warfare, the increasingly strong U.S. Navy was in possession of the waters around the eastern Solomons. The cost to both sides had been extremely heavy, and roughly even at sea and in the air. On land, Japanese casualties greatly exceeded those of the U.S. Marines and U.S. Army.

The Battle of Midway in June 1942 stopped the Japanese advance, but the Guadalcanal campaign was the true turning point of the Pacific War. As noted, the cost to the U.S. Navy included two aircraft carriers, five heavy cruisers (plus one Australian heavy cruiser), two light cruisers, 15 destroyers, three destroyer-transports, and one transport, plus about 615 aircraft of all services (including 90 carrier-based). Just under 5,000 sailors were killed, including 130 naval aviators and aircrew, plus 49 Marines embarked aboard ship along with 92 Australian and New Zealand naval personnel. Almost three times as many American sailors died at sea defending Guadalcanal as Marines and Army personnel died on it.

During the brutal six-month campaign, the U.S. Navy “abandoned” the U.S. Marines for a grand total of four days, yet that myth lives on. However, to the Corps’ credit, they remember and venerate the extraordinary sacrifice and valor of the Marines who held that embattled, disease-ridden island against repeated Japanese attacks, while the U.S. Navy has largely forgotten the extraordinary sacrifice and valor of those sailors who enabled the Marines to hold fast.

Over the next several months I will highlight several of the ships whose crews performed with exceptional valor such as Quincy (CA-39) at Savo Island, Jarvis (DD-393) in independent action, San Francisco (CA-38) in multiple engagements, Laffey (DD-459) in the Friday the 13th battle, and Alchiba (AKA-6), the only transport ever awarded a Presidential Unit Citation.