H-Gram 082: USS Asheville's Defiance and the "Dancing Mouse"

3 April 2024

Download a PDF of H-Gram 082 (1 MB).

This H-gram primarily covers the heroic actions of Lieutenant Commander Jacob Britt, the commanding officer of USS Asheville (PG-21), and Lieutenant Joshua Nix, the commanding officer of USS Edsall (DD-219), who chose to fight against overwhelming odds, rather than surrender, during the fall of the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia) in March 1942. They were true to the banner in Memorial Hall of the U.S. Naval Academy—“Don't give up the ship.”

I wrote the piece on Asheville and Edsall and sent it to the active flag officers prior to the Navy Flag Officers and Senior Executives Service (NFOSES) Symposium as a motivational piece (or at least an antidote to any griping about how hard things are now). It received good reviews from the CNO, VCNO and others, so I thought I would share with the retired flag community. At the end, I also share another piece I wrote (H-082-1—“Doc” and YMS-365) as an antidote to writing too many flag officers’ passing notes lately.

This will be my 17th year participating in NFOSES/Air Force Officer Training School (AFOTS). I offer the following as means to charge your batteries for the challenges ahead.

When I first took the job as Director of the Naval History and Heritage Command over nine years ago, I was visiting the U.S. Naval Academy Museum, which falls within my command. As we were going through the “attic” where art and artifacts are stored, I saw out of the corner of my eye a painting that caught my attention, and I had the curator pull it out for a closer look. It showed what looked to me like a Chinese gunboat, battered, blasted full of holes, boats shattered, and burning fiercely, straddled by shells in a battle against a couple ships that were keeping their distance. But what struck me was that, despite the severe damage, the gunboat was still returning fire, and large battle flags were flying high from both masts. The gunboat obviously had no intent of striking its colors. The painting was titled USS Asheville’s Defiance by the great maritime artist Tom Freeman.

Tom Freeman, USS Asheville’s Defiance. Courtesy of U.S. Naval Academy Museum.

I was perplexed, because I have been reading naval history since I was in kindergarten, and I did not know of this action. So, I looked in the “gospel” of naval history in World War II, Samuel Eliot Morison’s 15-volume History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, Volume III, Rising Sun in the Pacific – and all it said was “and USS Asheville was sunk. After further digging and learning the whole story, I decided I wanted that painting to hang in the most prominent spot in my office, because it told a story that I believed needed to be told.

USS Asheville’s Defiance

On 27–28 February 1942, a combined Dutch, U.S., British, and Australian naval force was decisively defeated in the Battle of the Java Sea, in what on paper should have been an even fight with a Japanese force, and the Allied war effort in the Dutch East Indies collapsed in a rout. (The lessons from this battle are why we have Rim of the Pacific [RIMPAC] exercise and NATO.) On 1 March, surviving U.S. forces were ordered to withdraw to Australia.

The patrol gunboat Asheville (PG-21), commissioned in 1920, had been withdrawn from Chinese waters based on intelligence that the onset of hostilities in the Far East were imminent. During the period January–February 1942, Asheville conducted patrols out of a port on the south coast of Java that no one can pronounce (Tjilatjap) that the sailors called “Slapjack.” As ordered, on 1 March, Asheville commenced a transit toward Australia. The ship’s power plant had always been cantankerous, and Asheville suffered an engineering casualty that reduced its speed well below its normal slow maximum of 12 knots. As a result, Asheville was slowly transiting alone, heading for a rendezvous point that had been compromised by communications security violations, and the Japanese were waiting.

On 3 March, Asheville was sighted by a Japanese scout plane, about 300 miles south of Java. She was then intercepted by two Japanese destroyers, backed up by the heavy cruiser Maya. Arashi and Nowaki were among the most modern in the Japanese navy, capable of over 35 knots, and each armed with six 5-inch guns (in three twin turrets) and eight powerful 24-inch “Long Lance” torpedoes (plus reloads). The elderly Asheville was armed with but three antiquated 4-inch guns. The Commander-in-Chief of the Asiatic Fleet, Admiral Thomas C. Hart, had once described the Asheville as “lacks the speed to run and lacks the guns to fight.”

Running was not an option. Surrender was an option, but Asheville’s commanding officer, recently promoted Lieutenant Commander Jacob “Jake” Britt (USNA ’29) chose to fight. From the Japanese perspective, the battle that followed was a total fiasco. The Japanese assessed Asheville as not worth a torpedo. However, it took the two Japanese destroyers more than 300 rounds to get the hopelessly outclassed Asheville to stop shooting back. Asheville’s crew simply would not give up.

As Asheville finally began to sink, sailors from the engineering spaces came on deck to find the bridge and forecastle mostly blown away, and most everyone who was topside already dead. Once in the water, a Japanese destroyer rescued one survivor, Fireman Second Class Fred Brown (later promoted to First Class while missing in action), presumably so they could positively identify the ship they had just sunk. The other survivors were left behind, and all perished along with those who went down with the ship. Brown was treated decently on the destroyer but would ultimately die in a Japanese prison camp from the combined effects of beatings and disease. Brown related his limited view of the battle to a survivor of the heavy cruiser USS Houston (CA-30) that would become the only account of the battle from the U.S. side and would not be known until after the war.

There is no way of knowing what Lieutenant Commander Britt did, other than choosing to fight, or how long he even survived the onslaught of Japanese shellfire. But as an Academy graduate of the interwar years, he was steeped in the tradition of John Paul Jones (“I have not yet begun to fight”) as well as the immortal dying words of Captain James Lawrence in the War of 1812 emblazoned on Commodore Matthew Perry’s flag in Memorial Hall, “Don’t give up the ship!” Jake Britt was true to those words.

The “Dancing Mouse”—USS Edsall (DD-219)

It may be possible to extrapolate Britt’s actions by those of another Academy graduate, Lieutenant Joshua Nix (USNA ’30) who was in command of the World War I-vintage destroyer USS Edsall (DD-219) in an action against the Japanese south of Java on 1 March 1942. Edsall was believed to be responding to the distress calls of the oiler Pecos (AO-6) sunk by Japanese carrier aircraft. In additional to its own crew, Pecos had on board the survivors of the seaplane tender (and former first U.S. aircraft carrier) USS Langley (AV-3, ex CV-1). The destroyer Whipple (DD-217) managed to rescue 233 survivors before sonar contacts on a Japanese submarine forced curtailment of the rescue, leaving about 500 survivors behind in the vast Indian Ocean, none of whom were ever found, despite a search.

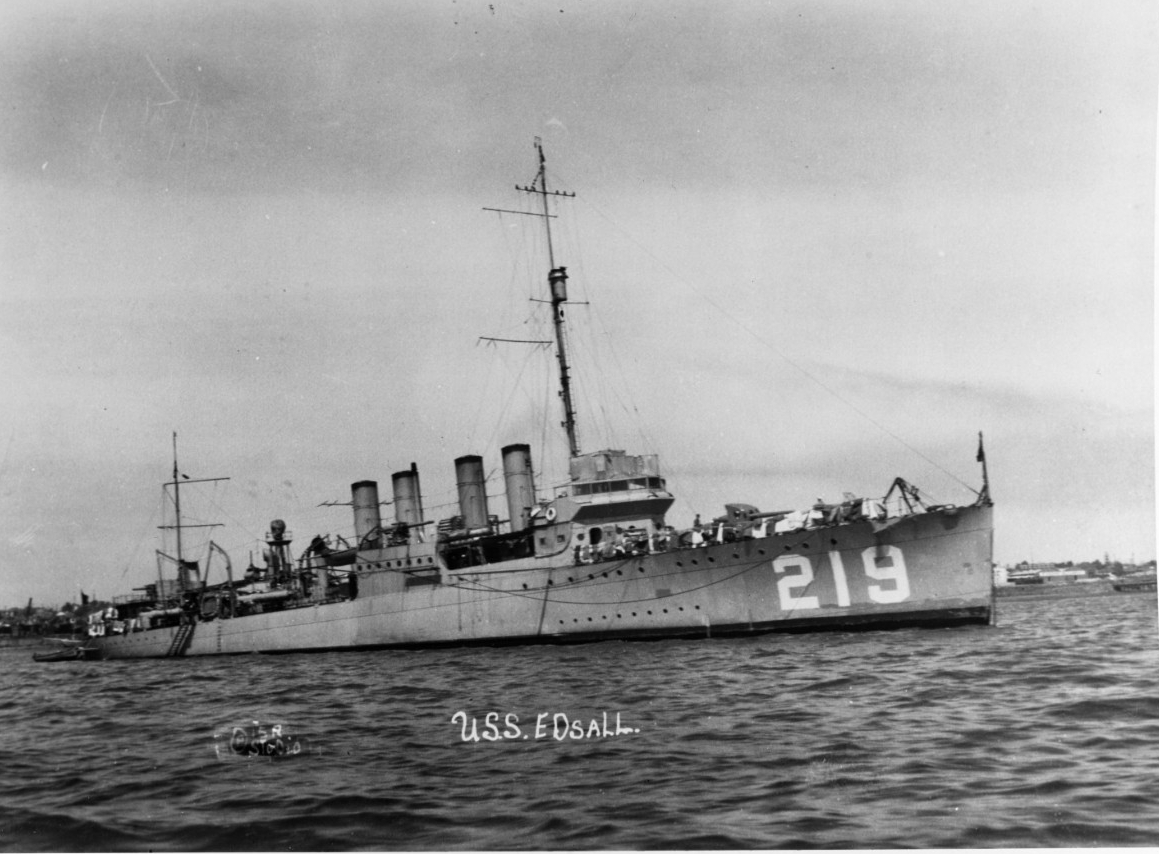

USS Edsall (DD-219), 1920–42. (NHHC, NH 69331)

Edsall ran right into the Japanese carrier force; four carriers, two battleships, two heavy cruisers, one light cruiser and six destroyers. Edsall came within 12 miles of the Japanese carriers before being spotted. The incensed Vice Admiral Nagumo (who had commanded that Japanese carrier force during the attack on Pearl Harbor) sent the two battleships (Hiei and Kirishima) and both heavy cruisers (Tone and Chikuma) to dispatch what they misidentified as a light cruiser.

With his speed already impaired by previous damage, Lieutenant Nix had no hope of outrunning the Japanese battleships and cruisers. Yet in the face of such overwhelming odds, just as Lieutenant Commander Britt would two days later, Lieutenant Nix chose to fight rather than give up the ship. And for almost two hours, with use of skillfully laid smoke screens and extraordinary ship handling, Lieutenant Nix caused over 1,400 Japanese 14-inch and 8-inch shells to miss, suffering only one hit—and Edsall nearly hit one of the cruisers with a torpedo. The Japanese likened the unpredictable maneuvers of Edsall to that of a “Japanese Dancing Mouse” (bred for their manic motions to entertain children).

Finally, completely embarrassed by the dismal showing of his surface ships against what they now knew to be an elderly destroyer, and despite the gathering dusk, the apoplectic Admiral Nagumo launched 26 dive-bombers from three carriers. Even so, Lieutenant Nix maneuvered to cause most of the bombs to miss, but there were just too many.

As Edsall began to sink, Nix turned the bow of the ship toward the Japanese in a final gesture of defiance. The survivors of Edsall conducted an orderly abandon ship, calmly supervised by an officer, presumably Lieutenant Nix, that the Japanese observed then proceed to the bridge, and who went down with his ship. The Japanese rescued only seven survivors, a mix of crew and U.S. Army Air Force pilots who had been aboard. Although treated decently aboard the Chikuma, all would later be executed by beheading in a Japanese prison camp. As a result, no one from Edsall survived the war.

The Payback

There is a postscript to the loss of Asheville. Three months later at the decisive Battle of Midway on 4 June 1942, despite having the advantage of surprise, the battle was going badly for the Americans. The air group of Hornet (CV-8) had overshot the Japanese carriers, as had the two dive-bomber squadrons from Enterprise (CV-6). The torpedo-bomber squadrons from the three U.S. carriers had become separated and engaged the Japanese piecemeal. Almost every torpedo-bomber was shot down. At that time, only one dive-bomber squadron from Yorktown (CV-5) was actually heading directly toward the four Japanese carriers.

The leader of the Enterprise air group, Lieutenant Commander Wade McClusky, knew his planes were already past the point of no return regarding fuel and he would have to decide whether to land on Midway Island or turn back and hope the U.S. carriers had closed the distance. At that critical moment, McClusky sighted a lone ship transiting at high speed. He correctly deduced that the ship was trying to return or catch up to the main Japanese force, and he chose to turn in the direction the ship was heading. The result was that the two Enterprise dive-bomber squadrons and the Yorktown squadron arrived over the Japanese carriers at the same time, resulting in mortally wounding three of the four.

What had happened was that the U.S. submarine Nautilus (SS-168), with Lieutenant Commander William Brockman (USNA ’27) in command—despite being repeatedly strafed, bombed and depth-charged (two bounced off the hull), and a torpedo that ran hot in the tube—kept trying to get in range of the Japanese carriers. Finally, Admiral Nagumo directed a destroyer to stay behind and keep the persistent submarine pinned down. That destroyer was Arashi, one of the two that had sunk Asheville and it was its high-speed transit back to the carriers that was instrumental in changing the course of the battle, and of the war.

The fatal flaw in the Japanese plan for the Midway operation was written right into their operations order, “The enemy lacks the will to fight.” Had the writers of the order in Japan paid attention the reports of the actions of Asheville, Edsall, Pecos, Houston, Pope (DD-225), Pillsbury (DD-227) and others in the fall of the Dutch East Indies, they should have reached a far different conclusion. The U.S. Navy was in fact willing to fight, even against the greatest of odds.

So, at every memorial service to sailors lost in battle or to the sea, the Navy makes a promise to them and their families that we will not forget their sacrifice. And if we expect sailors to fight and die for this country, the least we can do as a Navy and a nation is to remember them. In the case of Asheville and Edsall (and Pillsbury) there were no surviving American witnesses. As a result, there are no Medals of Honor, no Navy Crosses, no Presidential Unit Citation or even Navy Unit Commendation, for what by the Japanese accounts were among the most valorous actions in the history of the U.S. Navy. Neither Lieutenant Commander Jacob Britt nor Lieutenant Joshua Nix was ever honored by the name of a ship, but both are at the top of my short list of recommendations to the Secretary of the Navy for future ship names.

The reason the painting of USS Asheville’s Defiance is on my wall is because this vessel is representative of a number of ships and submarines from which none of their crews ever came home. There was no one left to tell their story, so as the Director of Naval History, I consider it my duty to tell their story, and to ensure the Navy keeps our promise never to forget. I deeply appreciate your help in keeping that promise. Thank you.

______________________________

Postscript: This content is taken from my remarks at the dedication of a monument to the 166 crewmen of Patrol Gunboat USS Asheville (PG-21) in Riverside Cemetery, Asheville, North Carolina on 3 March 2024. It includes background on Asheville as well as some of its commanding officers (6 of 16 would make flag, including two four-stars and two three-stars). Elliott Buckmaster would go on to be in command of USS Yorktown at Midway. James O. Richardson would become Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Fleet/Pacific Fleet, and would be fired by President Roosevelt for speaking the truth. A sailor on Asheville in 1937, Richard McKenna, would later write the award-winning novel, The Sand Pebbles, made into the 1966 movie of the same name.

___________________

Sources include: Naval History and Heritage Command Dictionary of American Fighting Ships (DANFS) for U.S. ships; combinedfleet.com “Tabular Record of Movement” for Japanese ships; Rising Sun, Falling Skies: The Disastrous Java Sea Campaign of World War II by Jeffrey R. Cox, Osprey Publishing, 2014; In the Highest Degree Tragic: The Sacrifice of the U.S. Asiatic Fleet in the East Indies During World War II by Donald M. Kehn, Jr., Potomac Books, 2017; The Fleet the Gods Forgot: The U.S. Asiatic Fleet in World War II by W. G. Winslow, Naval Institute Press, 1982; The Lonely Ships: The Life and Death of the U.S. Asiatic Fleet by Edwin P. Hoyt, Jove Books, 1977.