H-033-1: Yanagi Missions and Submarine Atrocities

During World War II, Japan was allied with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy under the Tripartite Pact (also known as the Berlin Pact) signed on 27 September 1940. It was technically a “defensive” alliance, which was one reason the Japanese didn’t declare war on the Soviet Union after Hitler invaded in June 1941. (The other was that the Japanese had been decisively defeated and suffered thousands of casualties in a series of clashes with Soviet troops along the border between Japanese-occupied Manchuria and Soviet-allied Mongolia in an undeclared war in 1939.)

As a later revision of the pact, there was agreement among the signatories to share technologies. However, the Germans viewed this provision as mostly a one-way street (although even they were surprised by Japanese torpedo technology). In addition, the Germans charged the Japanese exorbitant sums of money (tons of gold) for German technology and, for the most part, the Japanese had to come get it. Transfer of technology (along with strategic material) via surface ship quickly became a non-starter. The result was a series of submarine missions from Japan to German-occupied France intended to return to Japan with advanced German technology. Only one round trip was successful.

A significant factor in the failure of the so-called Yanagi (“Willow”) missions was that much of the coordination was conducted via German and Japanese diplomatic communications, which U.S. and British intelligence were reading almost as fast as the Germans and Japanese. As a result of this and extensive Allied radio intelligence, the Yanagi missions were compromised to the point that the Allies strived to not overplay their hand and give away the knowledge that the Japanese and German codes were being broken.

First Yanagi Mission: I-30

The first Yanagi mission was almost successful, commencing on 22 April 1942 when I-30 departed Penang, Japanese-occupied Malaysia, with a cargo that included blueprints of the Type 91 aerial torpedo and strategic minerals. I-30’s own Type 95 torpedoes (submarine version of the Type 93 “Long Lance” oxygen torpedo) were off-loaded and replaced with older torpedoes, as the Japanese did not want to share Type 95 technology at that point.

I-30 took a circuitous route around the Indian Ocean, and her embarked Aichi E14Y1 “Glen” floatplane conducted surveillance missions on Aden, Djibouti, Zanzibar, and Dar-es Salaam, before the submarine carried out periscope observation of Mombasa and Diego Suarez. This was part of a coordinated attack with I-10 and I-16 using midget submarines against British navy ships in Diego Suarez (the British battleship Ramillies was badly damaged as a result). Following the attack, I-30 headed for the Atlantic, remaining radio silent for the rest of the voyage. Although spotted by a South African Air Force aircraft off Cape of Good Hope, I-30 reached Lorient, France, without incident on 5 August 1942.

The Germans were unimpressed, believing that I-30’s engine and hull noise were too high for their purposes. However, the floatplane was painted in false Japanese colors and used in propaganda films to show the existence of a (fictional) Imperial Japanese Naval Air Corps operating from French bases. The Japanese left the floatplane in France, while the Germans provided (and the Japanese paid for) a radar detector, an upgraded anti-aircraft weapon (quad 20-mm), and a cargo that included an air defense ground radar, five G7a aerial torpedoes, three G7e electric torpedoes, torpedo data computers, sonar countermeasure rounds, rocket and glider bombs, anti-tank weapons, anti-aircraft fire control systems, 200 20-mm anti-aircraft guns, industrial diamonds, and 40 T-Enigma coding machines.

On 22 August 1942, I-30 departed Lorient and arrived at Penang on 9 October 1942. She was then ordered to deviate from her planned track and deliver ten of the T-Enigma machines to Singapore. Unable to communicate with the Japanese base at Singapore due to having outdated codes, the skipper of I-30 nevertheless managed to navigate into the harbor. Only then was I-30 provided with charts that showed the swept mine areas; despite this, I-30 struck a British mine upon exiting the harbor on 13 October and sank, with a loss of 13 of her crew. Some of the cargo was subsequently recovered by divers, but most of it was lost.

Mission by I-29 and U-180: Rendezvous in Mozambique Channel

On 9 February 1943, the German submarine U-180 (a Type IXD1 cargo-configured combat submarine) departed Kiel, Germany, with a cargo that included the leader of the anti-British Indian National Army, Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose, and his aide. Chandra Bose had become disillusioned that Germany would be of much use in gaining Indian independence from the British and hoped to gain better support from the Japanese.

After sinking a British tanker off the coast of South Africa, U-180 rendezvoused with the Japanese submarine I-29 in the Mozambique Channel on 26 April 1943. In a difficult rough sea operation over two days using rubber boats and open torpedo tubes (the skipper of I-29 described it as “a dive bomber’s dream come true”), I-29 transferred 11 tons of cargo to U-180, including two tons of gold as payment for previous transfer of German technology, plus four torpedoes, blueprints for the carrier Akagi (to assist the Germans with the Graf Zeppelin, their carrier under construction), and plans for the Type A midget submarine (used at Pearl Harbor). U-180 transferred blueprints for the Type IXC/40 submarine, quinine samples (to assist the Japanese with anti-malaria drugs), various other weapon and radar technology, as well as the two Indians. This is believed to be the only transfer of civilians between submarines of two different navies during the war.

U-180 successfully returned to Germany. I-29 gave British intelligence the slip and dropped the two Indians off at Sabang, Sumatra, instead of the planned drop-off at Penang. The Indians were flown to Tokyo and met with Japanese Prime Minster Hideki Tojo and Emperor Hirohito. Bose would lead the Indian National Army (composed mostly of Indian troops of the British Indian Army who had been captured by the Japanese and then sided with their captors) in action against British forces in India in 1944, but would be decisively defeated. He subsequently died as a result of burns in a plane crash on Formosa.

U-511's Mission

On May 1943, the German submarine U-511 “Marco Polo I” departed Lorient with a cargo that included the German ambassador to the Japanese puppet-government in China, the Japanese representative to the Tripartite Commission (Vice Admiral Naokuni Nomura ), and German scientists and engineers bound for Japan. While en route, U-511 sank two unescorted U.S. Liberty ships in the Indian Ocean, the SS Sebastion Cermeno on 27 June 1943 and SS Samuel Heintzelman (carrying ammunition) on 9 July 1943. None of Heintzelman’s crew of 75 survived when the ship blew up. On 16 July 1943, U-511 reached Penang, Malaysia, the first of a number of German U-boats (designated the “Monsun Gruppe”) that would operate from Penang in 1944 and 1945 with grudging support from the Japanese (I’ll cover this in a future H-gram, as two of them were sunk by U.S. submarines).

Despite being accidentally fired upon by a Japanese convoy escort, U-511 reached Kure, Japan, on 7 August 1943 and was turned over to Japan on 16 September, and re-designated RO-500. The Japanese conducted trials with RO-500 but were unimpressed by what they evaluated as low underwater speed, unreliable diesel engines, inadequate ventilation and cooling, and limited range. Some elements of the design were incorporated into new Japanese submarines. (Upon the surrender of Japan in August 1945, RO-500 sided with a rebel faction and sortied with the intent to continue fighting the Soviets. However, a Japanese floatplane tracked her down and convinced her crew to return to Japan and surrender on 18 August. She was handed over to the United States in September 1945 and deliberately scuttled off Japan in April 1946 to prevent technology from falling into Soviet hands).

The Italian Connection

Italy was allied with Nazi Germany during the first years of World War II. Upon the fall of France in June 1940 after the German Blitzkrieg offensive, the Italian navy established a submarine base at Bordeaux on the Atlantic coast of France so that Italian submarines could assist the Germans in attacking Allied shipping in the North Atlantic. Known by the acronym BETASOM, the Italians initially based 28 submarines at Bordeaux beginning in September 1940. These were augmented by four more in May 1941 that had previously been based in Italian East Africa (Ethiopia, Somalia) that came around the Cape of Good Hope after the British defeated the Italians in East Africa. The Italian submarines operating from Bordeaux were not especially effective, sinking 109 Allied ships for a loss of 16. However, the Italian submarines were larger than German submarines and had greater endurance, which made them attractive (to the Germans) for conversion into long-range cargo submarines, better suited for missions to transport strategic material to and from the Far East. As a result, the Italian navy converted seven of the BETASOM submarines to a transport configuration, with deck guns removed and torpedo tubes converted to fuel tanks.

The first Italian mission to the Far East commenced on 11 May 1943, when Commandante Cappellini departed Bordeaux with a cargo of 160 tons of mercury, aluminum, bombsights, tank blueprints, bomb prototypes, and other small advanced military equipment. Although battered by heavy seas around the Cape of Good Hope, the boat reached Sabang, Sumatra, on 9 July 1943, and then Singapore on 13 July, where her cargo was unloaded and she took on a cargo of tin, rubber, quinine, opium, and spices for the return voyage.

However, on 9 September 1943, Italy surrendered to the Allies. Capellini attempted to escape, but the Japanese prevented it, although the Italian skipper threatened to blow up the sub if the Japanese attempted to board. After negotiation, some of the Italian crew was interned by the Japanese while others agreed to continue to fight on the side of the Axis. Capellini was re-commissioned in the German navy as UIT-24 and, on 8 February, departed Penang, Malaysia, with her original cargo and a mixed German and Italian crew. However, the German oiler/supply ship in the Indian Ocean, Brake, was scuttled after being attacked by a British destroyer, forcing UIT-24 to return to Penang due to insufficient fuel. A second return attempt was also aborted. When the Germans surrendered in May 1945, the Japanese took control of the submarine and re-designated her as I-503, becoming one of two submarines to sail under the flag of all three Axis nations. She was surrendered to the United States at the end of the war and scuttled in 1946.

Giuliani departed Bordeaux on 16 May 1943 and reached Singapore on 1 August 1943. The submarine was taken over by the Germans, redesignated UIT-23, and commenced a return trip on 15 February 1944, only to be torpedoed and sunk by British submarine HMS Tally-Ho several days later. The next attempts by the Italians didn’t go well. Tazzoli departed Bordeaux on 21 May 1943 and was almost immediately sunk in the Bay of Biscay by Allied aircraft. Barbarigo departed on 17 June 1943 and was also sunk by Allied aircraft before getting very far in the Bay of Biscay. However, Torelli sailed on 18 June 1943 and reached Penang on 27 August. Torelli was also taken over by the Germans and re-designated UIT-25. When the Germans surrendered, the Japanese took her over as I-504, sailing with a mixed Italian, German, and Japanese crew. I-504 is believed to have shot down the last U.S. aircraft during the war, a B-25 bomber, technically after the Japanese had surrendered. Ammiraglio Cagni departed Bordeaux in early July 1943, but surrendered to the Allies at Durban, South Africa, when the Italian armistice was announced. Cagni was the last Italian submarine to make the attempt to reach the Far East.

Second Yanagi Mission: I-8

On 1 June 1943, the Japanese submarine I-8 departed Kure on the second Yanagi mission. I-8 would be the only Japanese submarine to complete a round trip. The boat carried 160 personnel including a second 49-man crew intended to man the German Type IXC/40 submarine U-1224 “Marco Polo II” upon arrival in Germany. On 27 June, I-8 departed Penang with a cargo of tungsten, rubber, tin, quinine, probably medicinal opium, and blueprints for the Type 95 torpedo. Upon rounding the Cape of Good Hope, I-8 was battered by severe storms, which damaged her aircraft hangar. In August, I-8 rendezvoused with U-161 south of the Azores and took on a new German radar detector as well as a German officer and two petty officer radiomen to assist with the entry to German-occupied France, arriving there on 31 August. U-161 was subsequently lost, with the three Germans on I-8 being the only survivors of U-161’s last patrol.

On 5 October 1943, I-8 departed Brest, France, with a cargo that included a Schnellboot (E-boat) engine, radars, sonar equipment, aircraft guns and anti-aircraft guns, bombsights, electric torpedoes, and naval chronometers. Passengers included a Japanese rear admiral and a captain (former naval attachés to Germany and France), three other German naval officers, one German army officer, several radar and hydrophone technicians, and four civilians. After crossing the equator, I-8 transmitted a report that was fixed by Allied high-frequency direction finding (HFDF), resulting in an aircraft attack that was unsuccessful. I-8 arrived in Penang on 2 December 1943 and Kure on 21 December 1943 after an otherwise uneventful transit. On 21 February 1944, under a new commanding officer, Commander Tatsunosuke Ariizumi, I-8 departed Kure en route the Indian Ocean to raid Allied commerce.

Third Yanagi Mission: I-34

On 13 October 1943, Japanese submarine I-34 departed Kure on the third Yanagi mission. Diplomatic traffic between Germany and Japan about her mission was intercepted and decoded. I-34 arrived in Singapore to pick up a cargo of tin, tungsten, raw rubber, and medicinal opium, along with Rear Admiral Hideo Kojima (naval attaché–designate to Germany) and several other passengers. The cargo load upset I-34’s trim, preventing her from being able to crash dive. With I-34’s departure delayed in order to fix the problem, Kojima opted to take the train to Penang and wait for I-34 there. However, waiting for I-34 outside Penang, alerted by sanitized Ultra intelligence message, was British submarine HMS Taurus.

On 13 November 1943, Taurus sighted I-34 outside Penang, and fired six torpedoes, one of which hit I-34 just below the conning tower, sinking her, and killing 84 of her crew. Twenty Japanese sailors survived trapped in the forward compartment and were able to escape the sunken submarine; 14 were ultimately rescued. I-34 was the first Japanese submarine to be sunk by a British submarine. The next day, Japanese sub chaser CH-20 attacked Taurus, causing Taurus to hit bottom and stick in the mud. However, CH-20’s depth-charge attack dislodged Taurus from the mud, whereupon the submarine surfaced and engaged CH-20 with her deck gun, severely damaging the vessel before a Japanese plane drove Taurus back under.

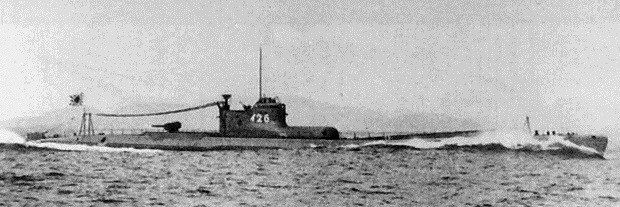

Imperial Japanese Navy Type B1 submarine (here, I-26) underway. Note floatplane hangar in front of the island and the launching catapult ramp on the foredeck (former Imperial Japanese Navy photo).

Fourth Yanagi Mission: I-29

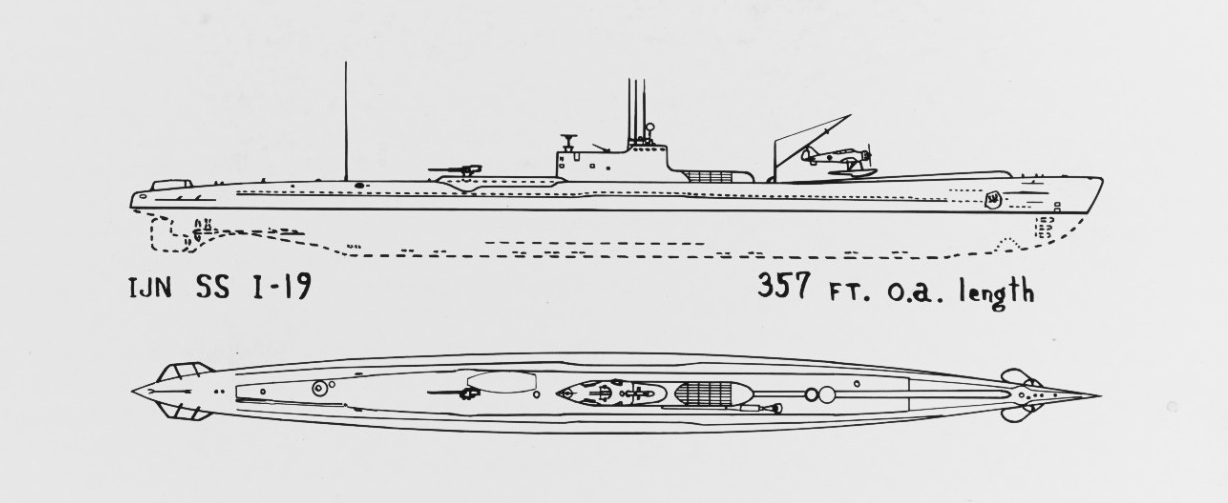

On 10 October 1943, Commander Takakazu Kinashi assumed command of I-29 in preparation for the fourth Yanagi mission. Kinashi had previously served as commanding officer of I-19 and had sunk the U.S. carrier Wasp (CV-7) southeast of Guadalcanal on 15 September 1942. With the same spread of torpedoes, Kinashi had damaged the battleship North Carolina (BB-55 ), forcing her to return to Pearl Harbor for several months of repair, and had also damaged the destroyer O’Brien (DD-415), which broke apart and sank a month later while attempting to reach Pearl Harbor for repair.

On 5 November 1943, I-29 departed Kure for Singapore, where she embarked a cargo of rubber, tin, tungsten, zinc, quinine, opium, and coffee. While I-29 was in Singapore, I-8 arrived from her successful transit from Brest, France, and transferred the German radar detector to I-29. I-29 also embarked 16 passengers, including Rear Admiral Kojima, who by quirk of fate had avoided going down with I-34. I-29 departed Singapore on 16 December 1943 and refueled from a small German supply ship in the Indian Ocean on 23 December. Allied codebreakers were able to determine I-29’s location several times, but no assets were able to intercept.

On 16 February 1944, I-29 rendezvoused with U-518, taking aboard three German technicians and two new kinds of radar detector. On 4 March 1944, I-29 was unsuccessfully attacked at night by a patrol plane off Cape Finisterre, Spain. On 10 March, I-29 picked up an escort of two German destroyers and two torpedo boast, along with air cover provided by five twin-engine Ju-88C-6 fighter-bombers. Tipped off by intelligence, the Royal Air Force attacked with two specially configured Mosquito fighter-bombers (armed with 57-mm cannon in the nose), escorted by four other Mosquitos, which engaged the German air escorts. One Ju-88 was shot down and the British claimed to have damaged I-29. Later in the day, ten more British aircraft attacked, including Beaufighter flak-suppressors and B-24 Liberator bombers, but all bombs missed I-29.

On 11 March 1944, I-29 safely arrived in Lorient. While the submarine remained in Lorient, Kinashi was invited to Berlin, where Adolf Hitler presented him with the German Iron Cross 2nd Class for sinking Wasp. (U-518 would be sunk in April 1945 on her tenth war patrol by hedgehogs from destroyer escorts USS Carter (DE-112) and Neal A. Scott (DE-769).

On 16 April 1944, I-29 departed Lorient, after her Japanese anti-aircraft guns had been replaced by German guns. I-29’s cargo included an HWK-509A-1 rocket motor (used on the Me-163 Komet rocket-powered fighter interceptor) and a Jumo 004B jet engine (used on the Me-262 Schwalbe jet fighter). In addition, I-29 carried drawings of a torpedo boat engine, a V-1 “buzz bomb” fuselage, TMC acoustic mines, bauxite, mercury-radium amalgam, and possibly uranium-235 “yellowcake.” I-29 also embarked 14 Japanese and 4 German passengers. In June 1942 in the South Atlantic, I-29 passed I-52 (the fifth Yanagi mission) heading the opposite direction, although the two did not communicate with each other.

On 14 July, I-29 arrived at Singapore and debarked her passengers, who took the blueprints and drawings ashore, but most of the cargo remained on board. On 15 July, Allied codebreakers intercepted a message that indicated I-29 had arrived in Singapore the day prior. Additional messages were intercepted that detailed I-29’s special cargo. On 20 July, I-29 transmitted a message with her detailed schedule for transit to Japan. The signal was intercepted and decoded by Fleet Radio Unit Pacific (FRUPAC) in Hawaii (successor organization to Commander Joe Rochefort’s Station Hypo of Midway fame), which alerted Commander, Submarine Forces Pacific (COMSUBPAC). COMSUBPAC sent an Ultra message to Commander D. W. Wilkins, commodore of a wolfpack (“Wilkins’ Wildcats”), which included submarines Tilefish (SS-307), Rock (SS-274), and Sawfish (SS-276), to intercept I-29 in the Luzon Strait.

Before departing Singapore on 22 July, I-29 embarked ten cadets from the submarine and navigation school. On 25 July, I-29 sighted a U.S. submarine, but continued en route Japan. On the evening of 26 July, at the entrance to Luzon Strait, I-29 was spotted running on the surface at 17 knots by Sawfish, under the command of Commander Alan A. Banister, on her seventh war patrol and his second war patrol in command. Sawfish fired four torpedoes at I-29, which were spotted by Japanese lookouts, but too late for Kinashi to take effective countermeasures. I-26 was struck by three torpedoes (which worked) and sank almost immediately. Three Japanese crewmen were blown overboard, but only one survived to reach a small Philippine island; 105 crew and passengers were lost with I-29.

The loss of the rocket motor and jet engine on I-29 set back Japanese programs for rocket and jet aircraft, which included the Mitsubishi J8MI Shusui “Sword Stroke” (Me-163–inspired) and the Nakajima Kikka “Orange Blossom” (Me-262–inspired). The blueprints did make it to Japan, but neither aircraft conducted test flights until July and August of 1945, when it was too late. (Like Hitler and the Me-262, the Japanese wanted to use the Kikka as a jet bomber instead of a fighter, even as the Me-262 used as a fighter was having devastating effect on Allied bombers in Europe, but too little, too late). Japanese navy policy was to advance an officer killed in battle one grade, but Kinashi was accorded the rare honor of being posthumously advanced two grades, to rear admiral. Commander Banister was awarded the first of two Navy Crosses.

RO-501 “Marco Polo II” Mission

When I-8 arrived at Brest on 31 August 1943, Lieutenant Commander Sadatoshi Norita disembarked with a 48-man crew and travelled to the Baltic Sea to train at the German U-boat training school facilities, and then to man and work up a new Type IXC/40 submarine, U-1224, which was formally transferred to the Imperial Japanese Navy during a ceremony at Kiel on 15 February 1944. The submarine was then commissioned into the Japanese navy on 28 February 1944 and redesignated RO-501 “Marco Polo II.”

On 30 March 1944, RO-501 departed Kiel with a cargo of mercury, lead, steel, uncut optical glass, aluminum and drawings, models and blueprints necessary to construct a Type IXC/40 submarine. In addition, RO-501 carried a full set of Me-163 rocket-powered interceptor blueprints. Also embarked was Captain Testsushiro Emi, who had made the at-sea transfer from I-29 to U-180 in the Mozambique Channel in April 1943, as well as a German radar operator and a German pilot. The next day, RO-501 arrived in Norway to embark fuel and supplies, departing on 1 April 1944 in company with U-859. On 11 May 1944, Norita sent a coded signal indicating RO-501 had been chased for two days. This signal was fixed by the Allied HFDF network and was the last one RO-501 would send.

On 13 May 1944, the USS Bogue (CVE-9) hunter-killer task group (TG 22.2) was operating in the vicinity of I-52’s track (not by accident) 500 nautical miles west of the Cape Verde Islands. Under the command of Captain Aurelius B. Vosseler, TG 22.2 consisted of the escort carrier Bogue and five destroyer escorts of Escort Division 51. At 1900, Francis M. Robinson (DE-220 ), having just joined TG 22.2 on 2 May, detected a submarine sonar contact at a range of 825 yards, causing Bogue to immediately turn away and Robinson to stream a “Foxer” noisemaker to decoy any German acoustic torpedoes that might have been fired. Robinson then fired a salvo of 24 hedgehog projectiles ahead of the ship and fired five salvos of new Mark 8 magnetic influence depth charges (which proved to be unreliable and were not used operationally in great numbers). The result was four underwater explosions, presumed to be destruction of a German submarine, which actually proved to be RO-501, lost with all aboard. However, as late as 22 June 1944, U.S. intelligence did not know that RO-501 had actually been sunk.

U-859, which departed in company with RO-501, transited to the Indian Ocean en route Penang to join with the German Monsun Gruppe. Along the way, she sank three ships, including the unescorted U.S. Liberty ship SS John Barry, which was transporting a cargo of three million silver coins (minted in America) from Aden to Ras Tanura, Saudi Arabia, as part of a U.S. agreement with the Saudi royal family to pay workers at the new ARAMCO oil refinery. Two crewmen were killed on board. Rumors quickly spread that she was carrying an even greater cargo of silver bullion, making her one of the most famous “lost treasure ships” of the 20th century, and a large effort in 1994 did succeed in recovering 1.3 million of the coins.

U-859 met a worse fate. Tipped off by intercepted and decoded communications, British submarine HMS Trenchant was awaiting U-859’s arrival off Penang, and hit her with one torpedo. U-859 sank in 160 feet of water with the loss of 48 of her crew including her skipper. Twenty crewmen survived trapped on the submarine, but made it to the surface; eleven were rescued by Trenchant and the other nine by the Japanese the next day.

Fifth Yanagi Mission: I-52

As I-29 arrived in Lorient, I-52 commenced the fifth Yanagi mission on 10 March 1944, departing Kure with two tons of gold and 14 Japanese engineers and technicians en route to Germany. Arriving in Singapore on 21 March, I-52 took on additional cargo of tin, tungsten, raw rubber, molybdenum, quinine, opium, and caffeine, and departed on 23 March. After passing the Cape of Good Hope on 15 May, the skipper of I-52 transmitted his first message to the Germans, which was intercepted and decoded by the F-211 “Secret Room” of U.S. Tenth Fleet and shared with the F-21 Submarine Tracking Room.

On 22 May, German submarine U-530 departed Lorient to rendezvous with I-52. On 2 June, the USS Bogue hunter-killer group departed Casablanca, French Morocco, earlier than originally planned. On 6 June 1944, the Japanese naval attaché in Berlin, Rear Admiral Kojima (who had arrived on I-29) signaled Tokyo and I-52 that the Allies had landed in Normandy, and that I-52 should prepare to divert to Norway should Lorient fall before she arrived. He also passed a date and location for I-52 to rendezvous with U-530. This message was intercepted and decoded as well. Another message from the Japanese embassy in Berlin was intercepted and decoded by the Fleet Radio Unit (FRUMEL) in Melbourne, Australia, which included time of the rendezvous. On 15 June, the Bogue group was ordered to intercept and destroy the I-52 and U-530 at the planned rendezvous location.

At 2115 on 23 June, exactly as planned, I-52 and U-530 rendezvoused 850 nautical miles west of the Cape Verde Islands. A German officer and two German radio operators transferred to I-52. The transfer of a radar detector went awry when it fell into the sea, but a Japanese sailor jumped in and saved it before it sank. At 2339, a TBF-1C Avenger of Composite Squadron 9 (VC-9) embarked on Bogue gained radar contact on I-29 running on the surface. Pilot Lieutenant Commander Jesse D. Taylor dropped flares to illuminate the target, followed by two Mark 54 (354-pound) depth bombs, which I-52 evaded and then submerged. Taylor then dropped a field of new secret sonobuoys and tracked the submarine before dropping a Mark 24 “mine,” which was a secret cover term for the new top secret “Fido” acoustic-homing torpedo, which resulted in a loud explosion.

A second Avenger arrived on scene and dropped more sonobuoys, detected the sound of screws, and dropped a second Fido, and the submarine was heard breaking up. However, in an unexplained anomaly, a German radio station received a garbled report on 30 June indicating I-52 was 48 hours from arrival, and German minesweeper escorts were dispatched to meet her. However, I-52 never arrived, and was lost with all 95 crew, 14 passengers, and three German navy personnel. The wreck of I-52 was found by American researchers in 1995 in the general location (off by “tens of miles”) of the aircraft attacks. Later analysis of the acoustic data suggested that the first Fido sank I-52 and what the second Avenger heard were U-530’s screws at some significant distance. I-52 was the last Japanese attempt to reach Europe by submarine.

Bogue, along with her escorts, was the first and the most successful of the U.S. anti-submarine hunter-killer task groups, accounting for 13 enemy submarines sunk in the Atlantic, two of them Japanese. The Bogue group would be awarded a Presidential Unit Citation and Captain Voseller would receive a second Legion of Merit.

U-530 returned to port, concluding her sixth war patrol. On her seventh war patrol, which coincided with the German surrender in May 1945, the submarine did not surrender as ordered, and showed up in Argentina on 10 July 1945. Although the Argentine naval ministry issued an official communiqué stating that no high-level Nazis were on board, that did not stop decades of conspiratorial speculation that Adolf Hitler and Eva Braun had escaped in disguise to Argentina along with other high ranking Nazis. This was fueled by anomalies in the voyage such as the missing submarine’s log, lack of crew identification, and the facts that the deck gun had been jettisoned and it had taken the boat two months to get to Argentina.

I-8 Atrocities

On 19 March 1944, Japanese submarine I-8, the only submarine to successfully complete a round-trip Yanagi mission, departed Panang and commenced an Indian Ocean patrol under the command of Commander Tatsunosuka Ariizumi. On 26 March 1944, I-8 torpedoed and sank the Dutch freighter Tjisalak 600 nautical miles southwest of Columbo, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka ). The survivors were taken aboard I-8, where 98 crew and passengers were massacred by swords and clubbing with wrenches and sledgehammers before being shot and thrown in the water. Japanese crewmen machine-gunned anyone who managed to jump overboard. Only five men managed to survive to be rescued by an American freighter.

On 31 March 1944, the E9W1 “Slim” floatplane from I-8 spotted the British armed merchant City Of Adelaide and vectored the submarine to intercept. After dark, I-8 hit City Of Adelaide with one torpedo. The ship sent a distress signal and was abandoned, but refused to sink. I-8 surfaced and sank the ship with gunfire, but could not find any of the lifeboats in the darkness, and the survivors were rescued a couple days later.

On 11 April, I-8 attacked the U.S. 10,400 ton T-2 tanker SS Yamhill, transiting from Bahrain to Freemantle alone with a cargo of oil intended for U.S. submarines. I-8 fired four torpedoes at Yamhill in succession at four-minute intervals, but two passed down her starboard side and two down her port side, giving Yamhill time to radio a distress signal. Finally, I-8 surfaced about 11,000 yards from the tanker and commenced what turned into a 12-hour chase as Yamhill made a run for it. Although I-8’s deck gun was larger (5.5-inch) than Yamhill’s bow-mounted, Navy-manned 5-inch gun, the higher mounting gave Yamhill a slight range advantage that helped keep I-8 at bay, with the submarine firing 20 rounds and Yamhill firing 38 rounds. Finally, a Royal Air Force PBY Catalina from the Maldive Islands showed up, forcing I-8 to submerge and enabling Yamhill to escape during the night.

On 29 June, I-8 hit the British armed passenger-cargo liner Nellore with two torpedoes as the vessel was en route from Bombay to Sydney with 174 passengers. I-8 surfaced to sink Nellore with gunfire and took one gunner and 10 passengers prisoner (fates unknown). Of those on board Nellore, 79 were lost, including 35 sailors, 5 gunners, and 39 passengers. Ten of the survivors sailed a lifeboat 2,500 nautical miles to Madagascar, while 112 survivors were rescued by a Royal Navy frigate.

On 2 July, the unescorted U.S. Liberty ship SS Jean Nicolet was transiting from Bombay to Sydney, when she was hit by two torpedoes from I-8 about 700 nautical miles south of Ceylon. I-8 then surfaced and sank the ship with gunfire, forcing the 99 survivors onto the deck of the submarine, where they were bound in pairs. Commander Ariizumi then ordered the master, the radio operator (who had gotten off a distress call), and one civilian be taken below. Then, with the encouragement and participation by Ariizumi, the survivors were systematically made to run a gauntlet of crewmen with knives and pipes to be severely beaten, stabbed, and ultimately murdered, while I-8 was destroying the lifeboats with gunfire.

When I-8’s radar detected an inbound aircraft, possibly responding to the distress call, the submarine submerged, leaving the bound survivors who hadn’t been killed yet on deck to drown. Somehow, 23 survived to make it to a life raft to be rescued 30 hours later by HMS Hoxa. Of the three prisoners, the civilian Francis J. O’Gara was discovered alive in a prison camp in Japan at the end of the war; the others did not survive. O’Gara had been moved from Hiroshima only one month before the atomic bomb was dropped on the city. In the interim, a new Liberty ship was named Francis O’Gara, becoming the only Liberty ship to be named after a living person, albeit unknowingly. Of the 24 survivors, 10 were Merchant Marine seamen, 10 were U.S. Navy Armed Guard, and 4 (including O’Gara) were civilian. Of the 76 who died, 31 were Merchant Marine, 18 were U.S. Navy Armed Guard, 17 were U.S. Army passengers, 7 were U.S. Navy passengers, and 3 were civilians.

I-8 concluded her gruesome patrol on 14 August 1944. Although not an excuse for war crimes, thousands of Japanese sailors and soldiers were dying at the time as a result of U.S. submarine attacks. Four days before the atrocity on I-8, the U.S. submarine Sturgeon (SS-187) sank the Japanese troopship Toyama Maru off the Ryukyu Islands. Of 6,000 Japanese troops of the 44th Independent Mixed Brigade on board, over 5,400 died, the highest death toll of any ship sunk by a U.S. submarine (and the fourth highest of any ship sunk by a submarine of any nation. The two highest tolls were German ships packed with thousands of civilian refugees sunk by Soviet submarines, and the third highest was a Japanese “hell ship” crammed with thousands of Allied prisoners of war and native forced laborers unknowingly sunk by a British submarine).

I-8, under a new commander, was subsequently converted to carry four Kaiten manned suicide submarines, but never embarked any. On 31 March 1945 near Okinawa, the destroyer USS Stockton (DD-646) conducted seven depth charge attacks over four hours on I-8, expending all her depth charges, but failing to sink her. The destroyer Morrison (DD-560) arrived just as I-8 surfaced, forcing her back under and then dropping a pattern of 11 depth charges that forced I-8 back to the surface. There, for 30 minutes at a range of 900 yards, I-8 fought with her deck gun before being sunk by Morrison. One unconscious gunner from I-8 was rescued by Morrison.

Following his “successful” war patrol on I-8, Commander Ariizumi was promoted to captain and given command of Submarine Division 1. Arriizumi embarked on the I-401. The I-400 class, of which three were completed before the end of the war, were the largest submarines in the world until the construction of ballistic missile submarines in the 1960s. Each I-400 could carry and launch (via catapult) three Aichi M6A Seiran high-speed torpedo-bomber floatplanes (which could drop the floats for even more speed, which, however, would preclude a recovery at sea). Allied intelligence was unaware of this aircraft until the war ended.

The Japanese planned to use the I-400s to mount a surprise attack on the Panama Canal, but this plan was scrapped in favor of one to use the planes to drop biological weapons on San Diego (Operation Cherry Blossoms at Night) in retaliation for the fire-bombing of Japanese cities. This operation was scheduled to be executed on 22 September 1945. In mid-1945, the Japanese became aware that a large U.S. naval force of over 15 carriers was gathering at Ulithi Atoll in the western Caroline Islands in preparation for the invasion of Japan. They devised a plan to conduct a surprise attack on the atoll, using the floatplanes of the I-400s and other Japanese submarines, disguised with American markings. The Japanese pilots objected to this deception as disgraceful, but were overruled. However, Japan surrendered before the Ulithi plan could be executed. Before surrendering, the Japanese submarines fired all their torpedoes and catapulted all the planes into the sea to destroy them.

I-401, with Ariizumi embarked, surrendered to the U.S. submarine Segundo (SS-398) on 29 August 1945 outside Tokyo Bay. Segundo put a five-man “prize crew” on board. The Japanese commander claimed that Ariizumi had committed suicide and his body had been put over the side through a hatch, although the prize crew never saw Ariizumi alive or dead, nor did they see any sign of a burial at sea, surreptitious or otherwise. This led to years of speculation that somehow Ariizumi had made it ashore and escaped justice and trial as a war criminal. Only three of the crewmen on I-8 at the time of the atrocities survived the war. One was an English-speaking American Japanese who had been trapped in Japan when the war broke out and pressed into the Japanese navy. He was given immunity to testify against the others and was allowed to return to the United States. The other two were convicted of war crimes, but, since they had been very junior sailors, their sentences were commuted by the Japanese government in 1955.

U-180’s Second Mission

On 20 August 1944, U-180 departed from Bordeaux, France, en route to Japan. She didn’t get very far and is believed to have been sunk by a mine in the Bay of Biscay on 23 August. However, there is speculation that trouble with her own snorkel was the cause of her loss with all 56 hands.

U-864’s Mission

On 5 December 1944, the new Type IXD1 (cargo-configured combat submarine) U-864 departed Kiel on a mission to carry cargo to Japan, code-named Operation Caesar. U-864’s cargo included Messerschmitt jet engine parts, V-2 ballistic missile guidance systems, and 65 tons of mercury. U-864 subsequently grounded, damaging her hull, on the way to Bergen, Norway. The submarine pens at Bergen were then bombed by British aircraft, delaying repairs. By this time, British codebreakers had sufficient time to crack some of the messages and were by then well aware of U-864’s mission. The British submarine HMS Venturer was vectored to intercept.

On 6 February 1945, U-864 was having engine and snorkel trouble, which caused the submarine to make a lot of noise. The skipper radioed that he would have to return to Bergen. Venturer detected U-864 on sonar, began to track her, and then spotted her snorkel. Hoping that U-864 would surface and enable a better shot, Venturer continued to trail U-864 until the U-boat counter-detected her and began to take evasive zig-zag action. Venturer still managed to maintain trail of the submerged submarine for three hours before finally firing a spread of four torpedoes at the target. U-864 counter-detected the torpedoes and maneuvered to avoid three of them, but was hit and sunk by the fourth, with the loss of all 73 aboard. This is the only known instance of one submerged submarine sinking another submerged submarine.

U-234’s Mission

On 25 March 1945, U-234 made the last attempt by a German submarine to reach Japan. Originally built as a Type XB minelaying submarine, she was damaged during construction and completed as a long-range cargo submarine, with only two stern torpedo tubes. U-234’s cargo included a crated Me-262 jet fighter, an Hs-293 radio-controlled glide bomb, the newest German electric torpedoes, numerous technical drawings, and 1,210 pounds of uranium oxide. Passengers included a German general, four German naval officers, civilian engineers and scientists, and two Japanese naval officers, one of whom was Commander Hideo Tomonaga, one of the two Japanese officers transferred from I-29 to U-180 in April 1943 in the Mozambique Channel. After repairs due to a collision with another German submarine, U-234 finally departed Kristiansand, Norway, on 15 April 1945.

On 10 May 1945, U-234 received German Admiral Doenitz’s order to surface and surrender. The skipper of U-234 radioed that he would surrender in Halifax, Nova Scotia, and then set a course for Hampton Roads, intending to surrender to the Americans and destroying all his sensitive gear along the way. Upon learning of the intent to surrender, Tomonaga and the other Japanese officer committed suicide and were buried at sea. The destroyer escort USS Sutton (DE-771) intercepted and took command of U-234 and brought her into Portsmouth Naval Shipyard. The exact purpose of the 1,210 pounds of uranium oxide remains unknown, as is what exactly happened to it, and its existence remained classified well into the Cold War. However, Japan did have cyclotrons and an atomic bomb project.

Sources include: NHHC Dictionary of American Fighting Ships (DANFS) for U.S. ships; combinedfleet.com for Japanese ships; uboat.net for German submarines; “Japanese Atrocities, SS JEAN NICOLET” at armedguard.com; and Axis Blockade Runners of World War II by Martin Brice, Naval Institute Press, 1981.