H-012-4: Guadalcanal, 1942—The Battle of Saturday the 14th

H-Gram 012, Attachment 4

Samuel J. Cox, Director NHHC

November 2017

The Japanese weren’t very good at quitting. Despite being thwarted in their plans to bombard Henderson Field on Guadalcanal on the night of 12/13 November, the operation to reinforce and retake Guadalcanal continued. The loss of the Hiei, the emperor’s favorite battleship, came as a profound shock to the Admiral Yamamoto and the Japanese navy leadership, perhaps even greater than the loss of the carriers at Midway. The purpose of the carriers, cruisers, and destroyers was to whittle down the American fleet before the ultimate clash of battleships that would decide the war, according to two decades of Japanese naval planning and doctrine. Losing some of them was expected. Losing a battleship was unacceptable. Rear Admiral Abe and Captain Nishida paid for the loss of Hiei with their careers and were promptly retired.

During the day of 13 November, both Admiral Yamamoto and Vice Admiral Halsey made plans for follow- on action. Yamamoto ordered Vice Admiral Nobutake Kondo to take the battleship Kirishima (which came through the battle before dawn that morning virtually unscathed), two heavy cruisers (Atago and Takao), and escorts to shell Henderson Field on the night of 14/15 November. Due partially to an increasingly acute Japanese fuel shortage, Kondo’s other two battleships, Kongo and Huruna (which had shelled Henderson Field in mid-October), were held back north of the Solomon Islands.

With the battered remnants of the late Rear Admiral Daniel Callaghan’s force in no condition to give battle, Halsey had few options. He had ordered the damaged USS Enterprise (CV-6) to get underway even with her forward elevator still jammed and get into the fight; Enterprise arrived in time for her aircraft to participate in the bombing of the Hiei and Japanese transports on 13 and 14 November, and some of Enterprise’s aircraft operated from Henderson Field due to the carrier’s reduced operational capacity. Although Halsey absolutely could not afford to lose Enterprise, the last operational U.S. fleet carrier in the Pacific, he took a major risk by detaching her two battleship escorts (USS Washington and USS South Dakota) and four destroyers, and violating every lesson learned from U.S. Naval War College war games (as Halsey later said), sending them into the confined waters of Iron Bottom Sound to oppose the next Japanese thrust. The four destroyers were all from different divisions, had never trained together before, and were picked because they had the most fuel. Washington and South Dakota had minimal experience working together as well. This completely ad hoc task force was designated TF 64, under the command of Rear Admiral Willis A. “Ching” Lee.

Lee was considered a master of naval gunnery, was extraordinarily technically adept, and reputed (rightly) to know more about radar than the radar operators. Lee was also a shooting enthusiast and was tied for the most medals (seven, including five golds) earned in Olympic competition (1920), a record that stood for 60 years. He had also put his shooting skills to use during the naval landings at Vera Cruz, Mexico, in 1914, deliberately exposing himself to draw fire and then shooting three snipers at long range. Lee also had an advantage in that both Washington and South Dakota were equipped with the latest SG search radar, and Lee had invested great time and effort on Washington (and before), developing the basic principles of radar-directed gunfire.

On the night of 13/14 November, shortly after midnight, two Japanese heavy cruisers, the Suzuya and Maya, shelled Henderson Field with almost 1,000 rounds, but succeeded in destroying only two Wildcat fighters and two SDB dive bombers, and damaging 15 other Wildcats, a far cry from what battleships Kongo and Haruna had done in October and what Hiei and Kirishima could have done the night before, but for the sacrifice of Callaghan’s ships. Two U.S. PT-boats tried, but were unable to disrupt the cruiser bombardment.

Maya and Suzuya subsequently rendezvoused with other Japanese heavy cruisers (Chokai and Kinugasa) under the command of Rear Admiral Gunichi Mikawa, but did not get far enough away from Guadalcanal before daylight and paid for their failure to effectively suppress Henderson Field. Marine and Navy planes attacked the Japanese cruisers, claiming several hits, but probably achieving no direct hits. However, at 0815 on 14 November, two SBD scout bombers from Enterprise located the Japanese cruisers. Flight lead Lieutenant Junior Grade Robert D. Gibson and his wingman shadowed Mikawa’s force for over 90 minutes. Gibson then conducted a solo dive-bombing attack on the heavy cruiser Kinugasa (which had nearly sunk USS Boise at the Battle of Cape Esperance), accurately planting his bomb just forward of the bridge and killing Kinugasa’s captain and executive officer (and others). Gibson was awarded a Navy Cross. A second set of Enterprise SBDs attacked Mikawa’s force. Maya shot down one of them, flown by Ensign P. M. Halloran, which crashed into the cruiser, igniting ammunition and a fire which killed 37 of her crew. Meanwhile, a strike of 17 SBDs from Enterprise, reacting to Gibson’s sighting reports, rolled in on Mikawa’s force with damaging near misses on the heavy cruiser Chokai and light cruiser Isuzu. Other SBDs severely damaged Kinugasa with multiple near-misses, resulting in flooding that caused the cruiser to capsize and sink at 1122, taking 511 of her crew down with her.

Meanwhile, as U.S. aircraft concentrated on Mikawa’s cruiser force, a 23-ship troop convoy under the command of Rear Admiral RaizoTanaka was proceeding virtually unmolested toward Guadalcanal under the mistaken impression that Henderson Field had been suppressed. The convoy’s luck ran out at 1250, when 18 Marine SBD dive bombers from Henderson and seven Enterprise TBF torpedo bombers (flying from Henderson) attacked. More waves of aircraft from the airfield and yet more from Enterprise also attacked. Bombers from Henderson turned around as fast as they could for more strikes until dusk. Even B-17s got in on the action: The large numbers of bombs they dropped got Tanaka’s attention, but, as usual, horizontal high-altitude bombing hit nothing. The dive bombers and torpedo bombers were a different story. Of the 23 ships (which included escorts), six transports were sunk and one turned about along with two destroyers after rescuing 1,562 survivors. Four other Japanese destroyers rescued another 3,240 survivors during the night. Despite the slaughter of troop transports, only 450 soldiers were lost thanks to the Japanese rescue operation, but none of those 4,500-plus troops made it to Guadalcanal. Tanaka was ordered to press on with four remaining transports and five destroyers, despite being certain he could not reach Guadalcanal before dawn on 15 November.

Japanese search planes sighted Lee’s battleship force heading toward Guadalcanal, but bungled the identification, reporting them as cruisers, giving Vice admiral Kondo a false sense of security. Conversely, during the day-long attacks on Mikawa’s cruisers and Tanaka’s transports, Kondo’s force had remained undetected. The U.S. had radio-intelligence intercepts that indicated the Kirishima was coming, just not exactly where or when. In typical Japanese fashion, Kondo came up with a complex battle plan. Flying his flag in the heavy cruiser Atago, he intended to personally lead the Bombardment Group of battleship Kirishima and another heavy cruiser Takao. Rear Admiral Kimura would lead a Screen Group of light cruiser Nagara (survivor of the Friday the 13th battle) and six destroyers to protect the Bombardment Group. Taking a lesson from Rear Admiral Abe’s failure two nights earlier, the Bombardment and Screen Groups would hang back west of Savo Island, and a Sweep Group, consisting of the light cruiser Sendai and three destroyers, would go into Iron Bottom Sound to see what was there first, this time expecting to find a few cruisers and destroyers.

Lee’s force got to Iron Bottom Sound first, and, based on intelligence and reconnaissance reports from aircraft and submarine, fully expected to encounter a major Japanese force that could include as many as three battleships, ten cruisers, and a dozen or more destroyers. Halsey had given Lee free rein once Lee’s force reached Guadalcanal, so Lee’s decision to engage a possible overwhelming force with his own hodge-podge force represented boldness and courage every bit as great as that of Callaghan and Scott. Because his force had not trained together, especially in night fighting, Lee opted to use the same single-column line-ahead formation as Callaghan had done two nights earlier and Scott had done at Cape Esperance. The advantages were the same as before: simplified control and decreased risk of fratricidal engagements with his own forces. The disadvantage, still not clearly grasped even by Lee, was that it presented a great target for long-range Japanese torpedoes. Lee’s force was arrayed in the following order: the four destroyers Walke, Benham, Preston, and Gwin, with a large 5,000-yard gap between the destroyers and the flagship Washington, which was followed by South Dakota. The column was nearly attacked by three U.S. PT-boats, which were unaware of Lee’s force.

At 2200 on 14 November, Kondo’s force (14 ships) executed the planned three-way split. Lookouts on destroyers in the Japanese Sweep Group quickly spotted Lee’s force, reporting “new-type cruisers.” At 2231, the Japanese flagship Atago spotted the U.S. force, but then Kondo quickly received a series of contradictory reports that confused his picture of the situation. One of the reports, from a float plane, stated the U.S. forces included “heavy cruisers or battleships,” while others were still reporting cruisers. Kondo decided that his light forces could handle the U.S. ships, and turned the Bombardment Group (still prepared for shore bombardment rather than with ready ammunition more suited for a surface engagement) to pass north of Savo Island rather than encounter the westerly-heading U.S. force head-on in the strait south of the island.

At about 2252, Washington’s SG search radar detected the Japanese Sweep Group at a range of about nine miles to starboard, well after Japanese lookouts had sighted them. By 2315, both Washington and South Dakota had the Sweep Group in sight, still to starboard. Lee’s destroyers, two miles ahead of the U.S. battleships, had yet to detect Japanese ships. At 2316, Lee gave the order to open fire when ready. Both U.S. battleships opened fire on the light cruiser Sendai at 18,500 yards, completely startling the Japanese as radar showed U.S. rounds straddling the Sendai. Sendai and the two destroyers accompanying her quickly reversed course. Another destroyer in the Sweep Group, Ayanami, had proceeded independently through the strait south of Savo Island.

At 2322, Walke, the lead U.S. destroyer (which, like the other three destroyers, did not have SG radar), sighted and engaged Ayanami. Benham also quickly took Ayanami under fire. As the two lead U.S. destroyers blazed away at Ayanami, the Preston (third in line) sighted the light cruiser Nagara and four destroyers of the screen force coming up behind the Ayanami at 2327 and opened fire on Nagara. The well-alerted Japanese cruiser and destroyers quickly demonstrated their night-fighting superiority, adhering to their doctrine to launch torpedoes before opening fire. Using the backdrop of Savo Island (and flashless powder) to their advantage, the Japanese quickly began registering hits on the U.S. destroyers while the unseen torpedoes were on the way. (U.S. doctrine was to save torpedoes for high-value units, which had yet to be spotted. Most of the U.S. torpedoes would go down with their ships.)

The Preston was staggered by multiple shell hits from Nagara, killing all hands in both firerooms and igniting torpedo warheads. More hits devastated the ship aft, killing the executive officer. (There is also some strong evidence that Preston was hit by “friendly fire” from Washington at the same time.) By 2336, Commander Stormes had to give the order to abandon ship, and only about 30 seconds later, the ship rolled over and then sank by the stern, taking 116 men and Stormes with her.

At 2332, Gwin (fourth in line) was hit by two shells in the after engine room, which also caused several torpedoes to slide out of their tubes overboard. Gwin swerved to port to avoid the sinking Preston, which shielded her from Japanese torpedoes that began to strike. Walke, already being staggered by multiple shell hits, was hit by a Long Lance just forward of the bridge. The torpedo detonated Walke’s forward magazine and blew the bow clean off. Sinking rapidly, Walke’s skipper, Commander Fraser, gave the abandon ship order. As Walke sank, her depth charges exploded, killing many of the men who had made it into the water, including Fraser. At the same time, another Long Lance struck Benham in the bow, causing no casualties, but structural damage that would quickly prove fatal to the ship. However, the Japanese destroyers had expended many more torpedoes than had actually hit, which were that many fewer that could be fired at Washington and South Dakota. So, the sacrifice of the destroyers might well have saved the U.S. battleships.

With all four U.S. destroyers sunk, sinking, or essentially out of action, the Japanese Screen Group slipped away almost unscathed. Ayanami, however, pressed home her attack on the crippled U.S. destroyers, but in doing so stood out from the backdrop of Savo Island, which gave Washington a clear target. Ayanami was quickly turned into a burning wreck dead in the water.

At 2330, after initially firing on the Japanese Sweep Group, South Dakota suffered a massive self-inflicted power failure, which knocked out her radars, communications, most of her guns, and the situational awareness of her skipper, Captain Gatch. As Washington passed the line of burning destroyers, she proceeded on the far side from the Japanese and remained unobserved. South Dakota passed on the near side and was silhouetted by the flames, but this also put her in Washington’s radar blind spot aft of the ship and caused Lee to lose track of where South Dakota was. When she restored electrical power, she opened fire again on the Japanese Sweep Group, which was now astern. The blast from number three turret set all three float planes on the quarterdeck on fire, briefly pinpointing South Dakota’s position to the Japanese before the concussion from the battleship’s next salvo blew two planes overboard; a third snuffed the flames.

Vice Admiral Kondo’s view of the situation was not very accurate, either, and only after about 2350 did he start receiving reports that consistently indicated U.S. battleships were involved. Even then he refused to believe it. Convinced that the screen group had decimated the U.S. force (and they had decimated the destroyer force), Kondo began to press into the strait south of Savo intent on executing the bombardment mission. By 2335, Washington’s SG radar was tracking Kirishima, but because of the uncertainty regarding South Dakota’s actual location, Lee withheld opening fire until he could sort it out.

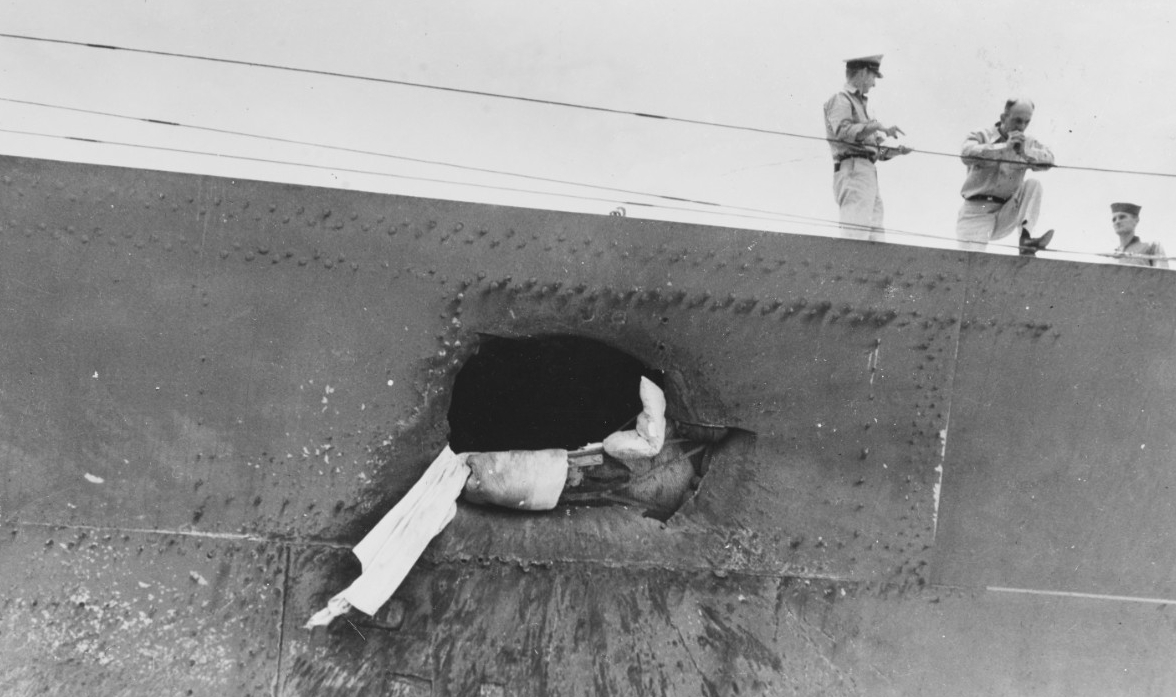

At about 2358, the two cruisers of the bombardment group fired Long Lance torpedoes at the South Dakota, which had inadvertently closed to within three miles as she grappled with her power and other material problems. At 0000 on 15 November, Atago illuminated South Dakota with a searchlight and a shocked Kondo only then became convinced he was facing battleships. Other searchlights caught South Dakota in their beams, and, in a matter of a few minutes, she was hit by 27 shells from five different Japanese ships, one of which was a 14-inch shell from Kirishima that failed to penetrate the battleship’s belt armor. However, damage to South Dakota’s topside was extensive, with many hits in the forward superstructure. Among other things, these destroyed the radar plot, disabled gun directors, set over 20 major fires, killed 39 crewmen, and wounded 59 more. Another Japanese destroyer fired four more torpedoes at South Dakota. Astonishingly, given the range, every torpedo fired by the Japanese missed. South Dakota fought back with her secondary armament, but her main battery got off only a few rounds due to lack of target data (two of the three guns in turret two were inoperative anyway due to the bomb that hit turret one at Santa Cruz).

When the Japanese opened fire on South Dakota, Lee no longer had any ambiguity about the large radar target Washington had been tracking, and the Japanese lost track of where Washington was. From a range of 8,400 yards, and in a matter of minutes, Washington smothered the Kirishima with at least nine and probably 20 radar-directed 16-inch shells that penetrated Kirishima’s armor into vital spaces; some penetrated below the waterline. Forty or more 5-inch shells from Washington also devastated Kirishima’s topsides, while one pair of 5-inch mounts also engaged the flagship Atago, which was still bore-sighted on engaging South Dakota. By the time Kondo figured out he was under fire from another battleship, it was too late for Kirishima. At 0013, the two Japanese heavy cruisers fired a total of 16 torpedoes at Washington, and, at 0020, Atago fired three more torpedoes. As in the case of South Dakota, every torpedo fired at Washington missed.

As South Dakota and the two damaged destroyers cleared the battle area, Washington was alone against 14 Japanese ships (including crippled Kirishima), still with dozens of lethal torpedoes. The situation did give Lee the advantage of knowing that every other contact was hostile, solving the fratricide problem. Meanwhile, Japanese command and control degenerated into chaos. Nevertheless, Kondo maneuvered his two heavy cruisers to boldly pursue Washington. Washington also had to maneuver to avoid two Japanese destroyers that were closing in on her position for a torpedo attack. Here, the speed of the new American fast battleships paid dividends. At this point, Lee opted to withdraw, and he proceeded well west and then south with about six Japanese destroyers in pursuit (the westerly course was to draw the Japanese away from the limping Benham and Gwin, which Lee had previously ordered to withdraw, and the battered South Dakota, which had already elected to withdraw).

At about 0040, two pursuing Japanese destroyers each fired a salvo of torpedoes at the retreating Washington, which required the battleship to take evasive maneuvers. At 0045, Kondo ordered Kirishima to withdraw and got no answer. A search party of two destroyers found Kirishima about five miles west of Savo Island in grave trouble. Her power plant was still functional, but her rudder was jammed over. Although her crew fought mightily to save her, they could not control the fires and flooding, and, at 0325, she capsized and sank. Many of her crew were rescued by three destroyers standing by. Another destroyer rescued much of the crew of the badly damaged Ayanami before she blew up and sank.

At 0215, South Dakota was finally able to restore some communications. Her topside fires had been so severe that Lee was concerned she had been lost. As Benham steamed slowly to the south, it became increasingly apparent that she was no longer structurally sound, and would have already broken apart had it not been for the relatively calm seas. However, the sea state was increasing rapidly enough that Gwin could not come alongside, but all of Benham’s crew were successfully transferred to Gwin by small boat. Gwin then attempted to scuttle Benham with a spread of four torpedoes, all of which typically malfunctioned. However, a 5-inch round into Benham’s magazine did the job.

The remnants of Rear Admiral Tanaka’s convoy reached Guadalcanal around 0400 and the four remaining troop transports deliberately ran themselves aground. The five destroyers then departed in an attempt to avoid the inevitable air attacks at dawn, taking with them many ground troops that had been rescued from the water the day before. Waves of U.S. aircraft from Henderson pounded the beached transports while others polished off abandoned, but still floating, transports from the previous day’s attacks. The destroyer USS Meade (DD-602), which had escorted a cargo ship to Tulagi, found herself in sole command of Iron Bottom Sound. Meade spent the day blasting the beached transports and Japanese positions ashore before rescuing survivors from Walke and Preston.

In the end, only about 2,000 Japanese troops made it ashore on Guadalcanal, with very little of their ammunition and supplies. Although fighting would continue on Guadalcanal for months, this marked the last major attempt by the Japanese to retake the island. Japanese operations transitioned to just trying to hold their part of the island and keep their troops from starving. The cost to the Japanese of the two major sea battles and the air attacks was two old (but fast) battleships, one heavy cruiser, three destroyers, 40 aircraft, and about 1,900 sailors, soldiers and aviators. The U.S. lost two anti-aircraft cruisers, seven destroyers, 26 aircraft, and 1,732 Sailors, Marines, and airmen. Although the price tag in blood was roughly even, the American losses would be replaced and the Japanese losses would not. The result of the battles of mid-November was a decisive victory for the United States that turned the tide of the Guadalcanal campaign in favor of the U.S. forces. America held the initiative for the rest of the campaign and the rest of the war. Nevertheless, the U.S. Navy was about to find out in two weeks that even just a handful of Japanese destroyers were extremely dangerous, resulting in yet another disaster at the Battle of Tassafaronga.

Summary of U.S. ships engaged in the battle of 14/15 November:

USS Washington (BB-56), Captain Glenn B. Davis commanding. Rear Admiral Willis A. “Ching” Lee (Commander TF-64) embarked. No damage. No casualties. Lee awarded a Navy Cross (subsequently promoted to vice admiral and dying of a heart attack days before the Japanese surrender).

USS South Dakota (BB-57), Captain Thomas L. Gatch commanding. Damaged; 39 KIA (including 1 Marine), 59 WIA. Gatch awarded a second Navy Cross. The battleship awarded a Navy Unit Citation for combined Santa Cruz and Guadalcanal actions.

USS Walke (DD-416), Commander Thomas E. Fraser commanding. Lost in action; 80 KIA, 48 WIA. Fraser awarded a posthumous Navy Cross. Allen M. Sumner–class destroyer DD-736 (converted to DM-24) named in his honor.

USS Benham (DD-397), Lieutenant Commander John B. Taylor commanding. Lost in action; 0 KIA/8 WIA. Taylor awarded a Navy Cross.

USS Preston (DD-379), Commander Max C. Stormes commanding. Lost in action; 117 KIA, 26 WIA. Stormes awarded a posthumous Navy Cross. Allen M. Sumner–class destroyer DD-780 named in his honor.

USS Gwin (DD-433), Lieutenant Commander John B. Fellows Jr., commanding. Damaged; 6 KIA, 0 WIA. Fellows awarded a Navy Cross. Gwin sunk at the Battle of Kolombangara in July 1943.