H-071-1: Loss of USS Hobson (DMS-26)

On the night of 26 April 1952, Hobson (DMS-26) was under the command of Lieutenant Commander William James Tierney, the destroyer’s eighth commanding officer. Tierney had previous command of a fast destroyer transport (APD), but had only been in command of Hobson for just over five weeks, only seven days underway and three and a half days with the Wasp (CV-18) task group.

Except where noted, the following account is directly from Pertinent Extracts of the Findings of Court of Inquiry, Collision of USS WASP and USS HOBSON of CNO Third Endorsement dated [redacted] December 1952 (The current Chief of Naval Operations [CNO] was Admiral William M. Fechteler):

On the night of 26 April 1952, the U.S.S. WASP (CV-18) was operating as a Carrier Unit with two destroyer-minesweepers acting as plane guards, the U.S.S. RODMAN (DMS-21) and the U.S.S. HOBSON (DMS-26). The Commanding Officer of the WASP, Captain Burnham C. McCaffree, was the Officer in Tactical Command. The WASP launched a group of aircraft about 2000 and directed it to conduct a simulated attack on the remainder of the naval task group enroute to the Mediterranean, approximately 50 miles to the South. The night was clear but dark, there was no moon, the sea was slight and the wind was 7–10 knots from 240°T [true bearing]. The ships were in Latitude 42°21' North, Longitude 44°15' West, [about 490 NM southeast of St. John’s Newfoundland] in 2700 fathoms of waters (about 3 miles). The three ships in the unit were in darkened condition except for red aircraft warning lights on top of the masts which were clearly visible to all the ships.

After the night launch the task unit was turned to course 102°T. The HOBSON was then bearing 245°T, distance 3000 yards from the WASP, and the RODMAN was bearing 090°T, distance 1000 yards from the WASP. Speed was 25 knots.

The Commanding Officer of WASP had a message sent at 2210 informing the plane guards that the probable recovery course for the returning aircraft would be 265°T and that the recovery speed would be 27 knots. Both plane guards received this message. For the WASP and RODMAN the change to the recovery course and speed would be simply a change of course and speed; however, the HOBSON, in addition to the change on course and speed, would have to adjust her present position of 245°T, distance 3000 yards from WASP to a position 175°T–185°T, distance 1000 yards from the WASP. Such a change in position is standard practice for naval ships operating with a carrier task unit. The Commanding Officer of the HOBSON, Lieutenant Commander William J. Tierney, discussed the evolution with the Officer of the Deck and indicated his intention to arrive on his new plane guard station by changing course to 130°T and, when the WASP bore about 010°T, to make a left turn to the recovery course. The Officer of the Deck, who had previously proposed a right turn and slowing down to 15 knots to fall into position, objected to this plan on the basis that a left turn to the recovery course was dangerous. Lieutenant Commander Tierney stated since the maneuver had to be expedited, that he would conn (personally direct course and speed changes) the HOBSON into its new position.

Note: Witness accounts state that the officer of the deck (who also had the Conn) was the Hobson’s executive officer, Lieutenant William A. Hoefer, who had been aboard for 16 months. The discussion between Hoefer and Tierney was so heated that Hoefer turned over the deck and the conn to Lieutenant Donald Cummings in order to continue the argument. When Tierney did not budge, Hoefer went out onto a bridge wing to cool off.

At about 2221 a signal to change course to 260°T and to change speed to 27 knots was properly made and executed. Both plane guards received the signal. The five degree variation between the probable recovery course and the course actually ordered would not appreciably change the planned maneuvers of the HOBSON. The position of the WASP and HOBSON at the time this signal was executed is shown on the attached chart.

The WASP made a normal turn to the right from 102°T to 260°T, successive positions being as indicated on the attached chart. The RODMAN had merely to maintain her approximate true bearing and distance from the WASP so turned simultaneously with the carrier. On the execution of the signal, the Commanding Officer of the HOBSON took the conn as prearranged with the officer of the deck and proceeded to change course and simultaneously to adjust his position. The HOBSON first turned right to 130°T and increased speed to 27 knots. After about two minutes, or at 2223 as noted on the chart and well before the WASP bore 010°T, the HOBSON came left to an average course of about 090°T which she held until the distance to the WASP had closed to about 1240 yards. The next move of HOBSON at 2224, directed by her Commanding Officer, was an inexplicable turn to the left using standard rudder. The Commanding Officer apparently soon realized that he was crossing the bow of the WASP and was in an extremely dangerous position, so he attempted to extricate his ship by increasing his rudder to full left, followed by hard left and emergency flank speed ahead.

Note: There is conflicting witness testimony in the record as to whether Tierney ordered a hard right turn just after the standard left turn suggesting he may have intended to conduct a Williamson turn, however if so, he told no one of his intent. At this point, Hoefer, the executive officer, came off the bridge wing warning, “Prepare for Collision!” multiple times. There was one minute and ten seconds between the time Tierney gave the first left turn order and impact.

The Commanding Officer of the WASP ordered an adjustment of the recovery course to 250°T, about the same time that the Commanding Officer of HOBSON ordered his final left turn. The heading of the WASP was then 258°T, having almost reached the prescribed course of 260°T. The Commanding Officer of the WASP personally transmitted the adjustment signal; however, as none of the bridge personnel of the RODMAN nor any survivors of the HOBSON heard the signal, the court was of the opinion that the Commanding Officer of the HOBSON also did not receive the signal. Since the HOBSON had already commenced her turn to the left, the signal, even if it had been received by the Commanding Officer, would not, at this time, have affected his manner of executing the evolution.

Almost immediately after the order was given to the WASP’s helmsman to make the 10° adjustment of course to the left, the Commanding Officer and Officer of the Deck of WASP noted the final left turn of the HOBSON. Captain [redacted] assumed the conn with a quick and correct order to the engines to “back emergency full speed.”

Note: The WASP’s officer of the deck, Lieutenant Robert Herbst, called out “we’re in trouble” to his commanding officer, Captain Burnham C. McCaffree, when he saw Hobson’s turn.

The combination of the HOBSON’s efforts to increase both speed and rate of turn and the WASP’s efforts to back emergency was not sufficient to avoid the collision and about 10 seconds after 2225 the WASP, which had swung to heading about 260°T and returned to heading 258ׄ°T, struck the starboard side of the HOBSON almost amidship at approximately a 90° angle and penetrated at least two- thirds through. The HOBSON broke in two, the forward section remaining afloat for about four minutes and the stern section sinking immediately. At the moment of impact the WASP was still making about 22 knots through the water although the engine speed had been slowed from 27 knots to about 7 knots. The emergency backing of WASP’s engines, combined with the resistance offered by the hull of the HOBSON, brought the WASP dead in the water while the HOBSON’s forward section was still close to the starboard bow of the WASP.

Note: The force of the impact rolled Hobson onto its port side. The aft half went under almost immediately, although 40 men managed to escape, some literally shot out of a scuttle by force of water pressure. The forward section remained entangled with Wasp for several minutes before sinking. One chief on Hobson was able to grab a pipe on Wasp and get aboard without going in the water. Everyone else was not so lucky, as survivors wound up in cold thick gelatinous goo of fuel oil. A pair of life rafts dropped from Wasp landed on a clump of five men, probably killing them as they were not seen again.

Search and rescue operations were commenced immediately by the WASP. The ship was lighted; searchlights were turned on; life rafts, life jackets, and other flotation gear were dropped in the water; eight boats were lowered into the water; recovery lines were put over from the flight deck to the water; and the deck edge elevator was lowered. The RODMAN closed the scene expeditiously, lowering her only boat. Three destroyers from the task group to the South joined rescue operations at 0015 on April 27 and the WASP temporarily ceased rescue operations long enough to recover her planes which by this time were very low on fuel. Thorough search and rescue operations were continued until 0730, April 27, when it was considered that no further possibility existed of finding additional survivors. Of the 237 officers and men aboard the HOBSON at the time of the collision, 176 lost their lives as a result of the collision and 61 survived the disaster. Following the collision, Lieutenant Commander Tierney was seen going in the water from the port side of the bridge and after three or four seconds was not seen again. There were no deaths or injuries to any personnel aboard the WASP.

Note: There are conflicting witness statements on how Lieutenant Commander Tierney went in the water. One account is that he dove toward the Wasp just before impact; either way, he could not swim and was not seen again.

The HOBSON was a total loss including all log books and records (a fact which, coupled with the death of the Commanding Officer, made the investigation more difficult), publications, equipment and other material aboard. The WASP received considerable damage to the bow section which has now been repaired.

After carefully weighing the testimony presented, the opinion of the Court, which has been approved by the Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Atlantic Fleet, is that the sole cause of the collision was the unexplained left turn made by the HOBSON about 2224. In making this left turn the Commanding Officer committed a grave error in judgment. As the Commanding Officer was not among the survivors his reasons for turning left will never be known. However three possible explanations for his actions are as follows:

1. He became completely confused and having lost the tactical picture, mistakenly continued to believe that he could turn left into position and so ordered “left rudder.”

2. He decided against his planned final left turn after he started the evolution but told no one of his decision and inadvertently ordered “left rudder” when he meant “right rudder” which, in fact, would have placed him near his intended position.

3. He made an error in judging his position relative to the WASP which, as noted was darkened except for the red aircraft warning lights and, thinking he was on WASP’s starboard bow, when he was in fact on the port bow, turned left to avoid crossing ahead.

Note: Commander in Chief, U.S. Atlantic Fleet was Admiral Lynde D. McCormick.

No other person is considered responsible for the collision. The Commanding Officer of the WASP handled his ship properly and when he sighted the HOBSON making her final left turn and took quick and proper action. His seamanship after the collision in carrying out search and rescue operations, in recovery of planes with comparatively low wind conditions across the fight deck and in bringing his damaged ship safely into port was of the highest order.

The condition of the material readiness of the WASP and HOBSON was good. No material, mechanical or electronic failure in either ship contributed to or caused the collision.

Note: Wasp’s surface search radar failed just as the ship began the turn into the wind. The port pelorus on Hobson fogged, so an accurate bearing to Wasp was not possible. The court concluded neither of these made a difference.

The gash in Wasp’s bow was 90-feet long and 15-feet deep. After the collision, Wasp was able to make about 10 knots, just enough to bring the ten aircraft in the air aboard. However, Wasp had to back its way 1,200 miles to port for repair, occasionally becoming uncontrollable with 600 feet of anchor chain and an 81 foot piece of hull plating hanging below. Entering dry dock at Bayonne New Jersey, WASP’s bow was replaced by that taken from Hornet (CV-12), then undergoing major conversion. Wasp was repaired in ten days and resumed its transit to the Mediterranean.

The Court of Inquiry was actually not unanimous in their conclusions, with a number of majority and minority opinions throughout, mostly about whether or how much blame should be ascribed to the Wasp or the executive officer of Hobson. The inquiry noted a number of watch-standing deficiencies and complacency aboard Wasp (and although Captain McCaffree was absolved of blame, he was only one of two skippers of Wasp [when the ship was not in reserve] not to make flag during that era). Two experienced destroyer skippers testified that it was the Wasp’s changing course right up until impact that was a significant cause; were it not for that, they argued, Hobson would have made it. The majority disagreed.

This was the sad end of a gallant ship that served with valor and distinction throughout World War II.

History of USS Hobson (DD-464/DMS-26)

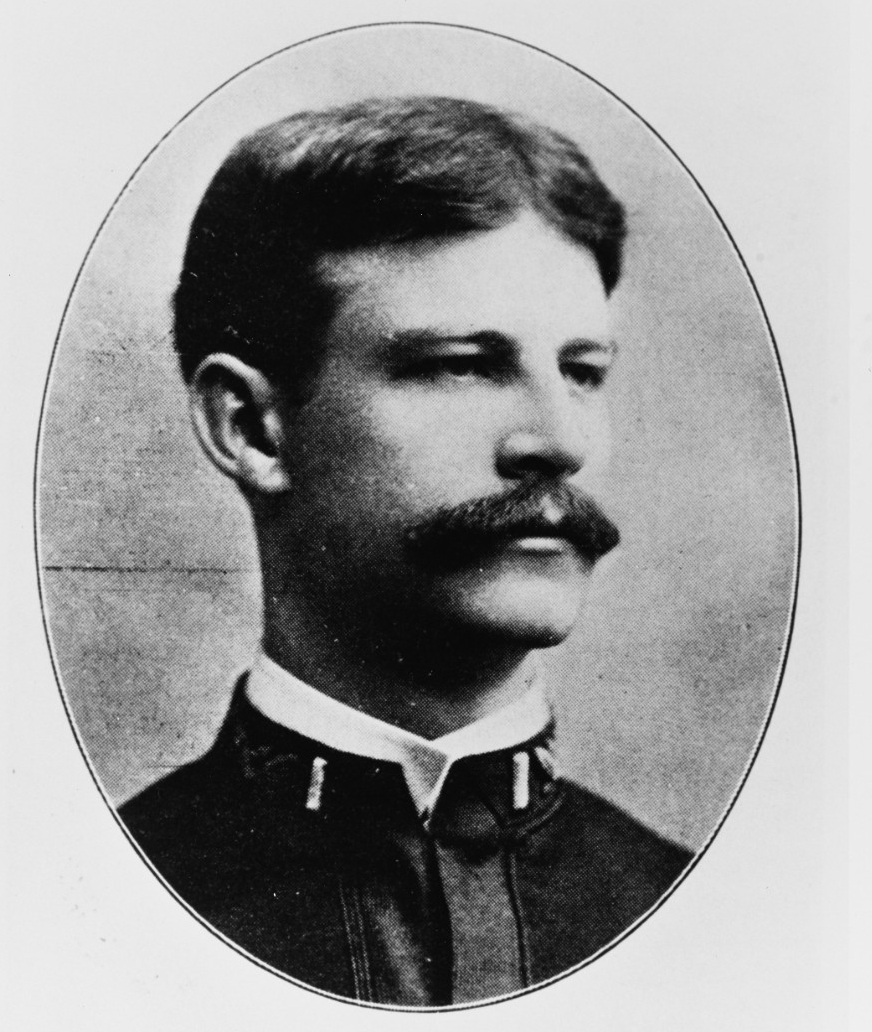

Namesake

The destroyer Hobson (DD-464) was named after Richmond Pearson Hobson, U.S. Naval Academy graduate, class of 1889, and Medal of Honor recipient for heroism in the Spanish-American War. On the night of 2–3 June 1898, the old collier Merrimac, under the command of Lieutenant Hobson and with a volunteer crew of seven, steamed into the entrance to Santiago de Cuba. Following orders from Rear Admiral William T. Sampson, Hobson and his crew attempted to scuttle Merrimac in the channel to block the Spanish squadron in port. However, alert Spanish shore batteries opened heavy fire and disabled Merrimac’s steering gear, leaving the ship and its crew adrift in the channel until the collier came in range of the Spanish ships in the harbor. These shelled Merrimac before it sunk, probably by a torpedo fired from Pluton. Unfortunately, Merrimac did not sink in a spot that would effectively block the channel.

Somewhat miraculously, Merrimac’s entire crew survived. The commander of the Spanish squadron, Admiral Cervera Pascual, personally motored out in his launch and picked up Lieutenant Hobson and his crew and treated them with great chivalry. While the Spanish held the crew as prisoners of war, U.S. newspapers wrote about the ship’s “suicide mission”; the men were idolized as national heroes before they even went home to a rock-star welcome when they were released after the Battle of Santiago.

All seven Merrimac crewmen were awarded the Medal of Honor—the only case I know of in which the entire crew of a ship received the medal. At the time, naval officers were not eligible to receive the Medal of Honor, so Hobson was not awarded one until 1933 by retroactive act of Congress (which also made him a rear admiral in retired status) and presented by President Franklin Roosevelt.

In the aftermath of the Spanish–American war, Hobson’s hero status rivaled that of Admiral Dewey, victor of the battle of Manila Bay; Hobson dined with President William McKinley and was swamped with speaking engagements, and he became known as “the most kissed man in America” as ladies everywhere literally swooned.

Hobson would go on to a political career as a U.S. congressman from Alabama, where he would be the only congressman from the South to vote for the women’s suffrage amendment of 1915 (which did not pass), and he would later become known as the “Father of American Prohibition.” In fact he had been ostracized by his classmates at U.S. Naval Academy (USNA) because of his total refusal to drink alcohol or smoke tobacco, yet finished first in his class. He was also close friends with inventor Nikola Tesla, who was the best man at Hobson’s wedding.

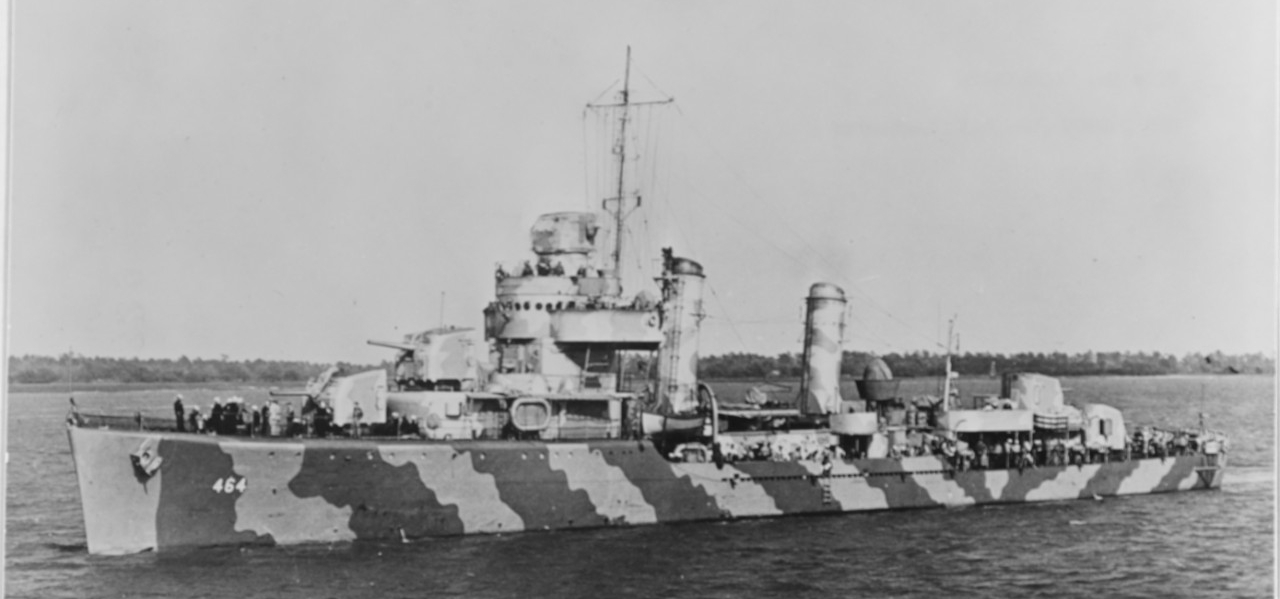

The Ship

Hobson was one of 66 Gleaves-class destroyers, authorized and laid-down as part of a belated pre–World War II U.S. naval build-up. The design of the Gleaves-class destroyers preceded the more numerous Fletcher-class destroyers, but both classes were built concurrently, all being commissioned after the start of the war. Hobson was laid down at the Charleston Navy Yard in South Carolina on 11 November 1940. It was launched on 8 September 1941, sponsored by Hobson’s widow, Grizelda. Hobson was commissioned on 22 January 1942.

Hobson was 348-feet long and displaced 1,630 tons. The destroyer had four boilers and two shafts and was capable of 37.5 knots. Sources conflict on its initial armament (which varied amongst the Gleaves-class), but its main armament consisted of four single 5-inch guns and two quintuple 21-inch torpedo tube launchers. It also had two depth charge racks. Its antiaircraft armament was upgraded to two twin 40mm guns and 7 20mm guns, plus it was fitted with four or six K-gun side-throwing depth charge launchers.

Under the command of Lieutenant Commander Kenneth Loveland (USNA ‘33), Hobson was assigned to Destroyer Division 20 (DesDiv 20) in Destroyer Squadron 10 (DesRon 10). After shakedown and training in Casco Bay, Maine, Hobson arrived at Norfolk on 1 June 1942. The ship spent the next four months screening the aircraft carrier Ranger (CV-4) for convoy escort operations along the U.S. East Coast and Caribbean to the Panama Canal.

Operation Torch—The Invasion of North Africa—November 1942

DesDiv 20, under the command of Captain James L. Holloway, Jr. (future four-star and father of CNO James L. Holloway III), was assigned to screen Ranger, escort carrier Suwanee (CVE-27), and light cruiser Cleveland (CL-55) for the Atlantic transit and invasion of Vichy French North Africa. During the Naval Battle of Casablanca on 8–10 November, the Vichy French resisted. Hobson and other DesDiv 20 destroyers protected Ranger from attacks by French submarines; four torpedoes from Le Tonnant missed astern Ranger, but prompt counterattack by DesDiv 20 destroyers Ellyson (DD-454) and Hobson prevented the submarine from getting closer.

For more on Operation Torch, see H-013-4 Forgotten Valor—Operation Torch.

Atlantic Convoy Operations—1943

After the success of Operation Torch, Hobson returned to the East Coast for more convoy escort duty. On 2 March 1943, Hobson rescued 45 survivors of the British cargo ship SS St. Margaret, which had been sunk by German submarine U-66 four days previously. The survivors had rigged one life boat with a sail, with 35 men aboard and towing a raft with ten more aboard, and had sailed over 90 miles from the point of sinking. Hobson disembarked the survivors in Bermuda. Beginning in April 1943, Hobson operated out of Argentia, Newfoundland and in July 1943 escorted a convoy taking British Prime Minister Winston Churchill to the Quebec Conference.

Operation Leader—Air Attack on German-Occupied Norway—December 1943

On 4 August 1943, Hobson sailed with Ranger to operate out of Scapa Flow with the British Home Fleet, guarding against a potential foray by German battleship Tirpitz. Hobson was inspected by Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox and Commander, U.S. Naval Forces Europe, Admiral Harold R. Stark.

In October 1943, a U.S. Task Force under the command of Rear Admiral Olaf M. Hustvedt, with Ranger, heavy cruiser Tuscaloosa (CA-37) and DesDiv 20, departed Scapa Flow to launch an air-strike on German-occupied Norway, designated Operation Leader. On 4 October, aircraft from Ranger struck Bodo (just north of the Arctic Circle) and Sandnessjøen, sinking or beaching five German (or German-controlled) tanker and cargo ships and damaging another seven, catching the Germans completely by surprise. Two German aircraft were shot down while trying to find Ranger, 1.5 of them by Lieutenant (j.g) Dean “Diz” Laird, who would go on to be the only U.S. Navy ace to shoot down German and Japanese aircraft.

For more information, see H-022-3—Operation Leader.

Bogue Hunter-Killer Group—March 1944

In March 1944, Hobson joined ASW (“Hunter-Killer”) Task Group 21.11 centered on escort carrier Bogue (CVE-9). The Task Group caught up with U-575, which had sunk British Corvette HMS Asphodel on 10 March (and nine cargo ships on nine previous patrols). Lookouts on the destroyers sighted an oil slick that led to a sonar contact and U-575 was depth-charged to the surface by Hobson. Allied units then swarmed the U-boat, which was sunk by the combined gunfire of Hobson, Haverfield (DE-393), Canadian frigate HMCS Prince Rupert, along with depth bombs from an Avenger of VC-95 off Bogue and a British RAF B-17 Flying Fortress. Somewhat amazingly, 37 of U-575’s crew of 55 survived the onslaught. Hobson would share in the Presidential Unit Citation awarded to the Bogue Hunter-Killer Group. Commander Loveland would be awarded a Legion of Merit with Combat “V” for the action.

For more about Hunter-Killer action, see H-Gram 064 Close Quarters ASW.

Operation Neptune—D-Day Landings on 6 June 1944

On 21 April 1944, Hobson and DesDiv 20 departed Norfolk to participate in Operation Neptune, the naval part of the Operation Overlord “D-Day” landings in Normandy, France. Hobson was assigned to the Utah Beach assault group under Rear Admiral Don P. Moon, as part of Bombardment Group 125.8, which included battleship Nevada (BB-36), heavy cruisers Tuscaloosa and Quincy (CA-71), British light cruiser HMS Black Prince (81), monitor HMS Erebus (I02), ten U.S. destroyers, four British destroyers, and a Dutch gunboat. Hobson initially screened Rear Admiral Moon’s flagship Bayfield (APA-33). Hobson, along with Corry (DD-463) and Fitch (DD-462) then led the first waves of landing boats through the swept channel before taking up fire support positions off Utah Beach.

At 0530 on 6 June, German shore batteries opened fire. The order for the destroyers to counter-fire was given at 0536, 14 minutes ahead of schedule. Hobson fired on multiple key German positions in order to protect the landing craft as they hit the beach. When Corry was hit and sunk by a German 8.25-inch shore battery, Hobson moved into Corry’s position to continue shelling the German position. Corry suffered 24 killed and 60 wounded, and was the most significant U.S. Navy ship loss on D-Day (although other ships would be lost in the week that followed).

For more about Operation Neptune, see H-Gram 031.

Naval Battle of Cherbourg—25 June 1944

Following the D-Day landings, the Allied advance on the critical port of Cherbourg stalled due to stout German defenses, despite being cut off from the rest of France. This was giving the Germans time to destroy the port facilities that would be needed to support any Allied advance across France. A naval task force was formed to provide heavy gunfire support to an all-out assault on Cherbourg from landward by three U.S. Army infantry divisions. Cherbourg was heavily defended from the sea by numerous concealed and hardened gun positions. In complete violation of Lord Nelson’s dictum, “a ship’s a fool that fights a fort,” the Allies planned to do exactly that.

Combined Task Force 129 was under the overall command of Rear Admiral Morton Deyo, who also commanded Battle Group 1. It consisted of battleship Nevada, heavy cruisers Tuscaloosa and Quincy, light British cruisers HMS Glasgow and HMS Enterprise, and six U.S. destroyers. Battle Group 1’s mission was to shell German-occupied Cherbourg, the inner harbor forts and positions to the west.

Battle Group 2 was commanded by Rear Admiral Carleton F. Bryant. The group included battleships Texas (BB-35), and Arkansas (BB-33) and five U.S. destroyers including Hobson. (It also included Laffey (DD-724, later known as “the ship that would not die” after multiple kamikaze hits, as well as O’Brien [DD-725], commanded by Commander William Outerbridge who had fired the first shot of the Pacific war in command of Ward [DD-139] sinking a Japanese midget submarine just before the attack on Pearl Harbor).

Battle Group 2’s mission was to take out the most powerful German strong point defending Cherbourg, Battery Hamburg. Situated on high ground, Battery Hamburg’s 11-inch guns could out-range the 14-inch guns on Texas and Arkansas.

The battle commenced at 0950 on 25 June 1944 and lasted until 1500 as the battleships and the fort engaged in a heavy gunnery duel. Texas was hit by an 11-inch shell, and three destroyers were hit by duds. The U.S. ships were repeatedly bracketed and German fire appeared to be highly accurate within 15,000 yards but was concentrated on the battleships. Hobson and other destroyers maneuvered close enough to hit targets 2,000 yards inland, which proved highly beneficial to the advancing U.S. infantry. By the end of the battle, gunfire from the U.S. and British ships had disabled 22 of 24 targets, but with no certainty the heavily casemated gun positions were permanently out of action (once captured by the U.S., it was later determined that most of the damaged guns were no longer serviceable). Cherbourg quickly fell after this action.

Commander Loveland would be awarded a Silver Star for his actions at Normandy and Cherbourg. The citation provided a description of the action at Cherbourg:

Maneuvering his ship through heavily mined waters under severe and accurately controlled gunfire to protect vessels of the Western Task Force Area from enemy surface forces and submarines, Commander Loveland drove his ship through heavy gunfire on two occasions to lay a protecting smoke screen inshore of the capital ships and by splendid ship-handling and smoke laying, saved the heavy ships from possible serious damage or possible loss.

Operation Dragoon—Invasion of Southern France—15 August 1944

Following the D-Day landings in Normandy, many of the U.S. ships involved proceeded to the Mediterranean for landings in the Southern France, termed Operation Dragoon. Three beaches were selected between Hyeres and Cannes, designated west-to-east: Alpha, Delta, and Camel. The Delta Assault Force, under Rear Admiral Bertram Rogers included: the gunfire support group, TG 85.12, under the command of Rear Admiral Bryant; battleships Texas and Nevada; light cruiser Philadelphia (CL-41); Free-French light cruisers George Leygues and Montcalm; eight destroyers of DesRon 10 (including Hobson); four Free-French destroyers; and other smaller gun vessels.

At H-hour (hour of initiation) 0800 on 15 August, Hobson provided spotting services for Nevada and then provided direct fire support to troops going ashore. In 15 minutes, the shore defenses were destroyed and the troops landed at Delta Beach (near Saint-Tropez) with minimal opposition. Following the successful landing, Hobson resumed Mediterranean escort duty.

On 2 October 1944, Hobson was departing the French port of Marseilles before dawn and into the teeth of a fierce gale. Lookouts sighted the Liberty Ship SS Johns Hopkins in distress. Johns Hopkins had arrived from Oran, Algeria with 600 U.S. troops on board when the vessel was blown into an unswept mine area and struck a mine. Despite the mine danger, Hobson made multiple attempts to come alongside Johns Hopkins to take off the troops, but waves battered the two ships together. Only superb ship-handling by Commander Loveland prevented serious damage. Finally, Hobson stood nearby as the ships drifted 13 miles through unswept waters until daybreak to rescue survivors, in case Johns Hopkins sank. Fortunately, Johns Hopkins stayed afloat and a tug towed the vessel into Marseilles. Commander Loveland was awarded a Navy and Marine Corps Medal for this action.

Destroyer–Minesweeper Conversion—October 1944

With the European naval war winding down, the eight remaining destroyers of DesRon 10 returned to the U.S. in October 1944 where all underwent conversion to a destroyer–minesweeper configuration. This involved removal of the aftermost 5-inch turret (Mount 54) and replacing it with gear for sweeping acoustic mines. Hobson was redesignated as DMS-26. Under a new commanding officer, Commander Joseph I. Manning (USNA ‘33), Hobson transferred to the Pacific as part of Mine Squadron 20 (MinRon 20) via the Panama Canal, arriving at Pearl Harbor on 11 February, before proceeding via Eniwetok to Ulithi Atoll to stage for the invasion of Okinawa.

Operation Iceberg—Invasion of Okinawa—April 1945

On 19 March 1945, ten destroyer minesweepers of MinRon 20 departed Ulithi and made a direct transit to Okinawa, arriving before the main force. As it turned out, the destroyer-minesweepers provided protection to regular minesweepers and for the most part were used as regular destroyers. Hobson was paired with Emmons (DMS-22) on radar picket duty, before Hobson assumed fire support duty providing night illumination to troops ashore on Okinawa. (Emmons was sunk on 6 April 1945 after being hit by five kamikaze aircraft.)

On 13 April 1945, Hobson was reassigned to radar picket duty to replace destroyer Mannert L. Abele, the first ship sunk by an Ohka “Cherry Blossom” rocket-assisted manned kamikaze bomb the previous night (84 dead and over 30 wounded), on a picket station 75 NM (nautical miles) northwest of Okinawa. With Hobson were destroyer Pringle (DD-477) and two landing craft infantry (LCI) intended to provide additional antiaircraft support to the radar picket ships, but grimly known as “pall bearers.”

At 0500 on 16 April, lookouts on Hobson sighted 15 Japanese aircraft on an incoming raid. Initially driven off by antiaircraft fire, the Japanese planes continued to circle until 0853 when one plane dove on Pringle. The kamikaze was shot down by the combined gunfire of Hobson and Pringle. Another kamikaze was downed by Pringle. However at 0920, one kamikaze made it through the antiaircraft barrage and struck Pringle in the bridge. The plane crashed through the superstructure to the deck abaft the forward stack. Either one 1,000-pound bomb or two 500-pound bombs penetrated deep into the engineering spaces resulting in a massive explosion that broke Pringle in two, sinking the destroyer in under six minutes.

At about 0922, another kamikaze dove on Hobson from the starboard side. The plane was blown apart by a 5-inch shell from Hobson, but a 250-pound delayed action bomb from the plane hit the deckhouse, starting fires in the gunnery workshop, machine shop and electrical shop, blowing a hole in the deck over the forward engine room, mangling steam and power lines. While Hobson’s damage control teams fought the fires, the gunners downed two more kamikazes making a run on the ship while an LCI shot down a third. Hobson’s fires were out in 15 minutes and emergency power restored in 35 minutes. The ship’s casualties were comparatively light with four men killed and eight wounded. Hobson then set about with the LCI’s in rescuing survivors of Pringle, which suffered 62 dead. Hobson picked up 136 of Pringle’s 258 survivors (three later died of wounds).

For more on this phase of the Battle for Okinawa, see H-Gram 045—Okinawa Part 2.

Hobson made it to Kerama Retto (near Okinawa) under its own power for interim repairs, but damage was severe enough to require the ship to return stateside for repairs. With West Coast yards chock full of ships under repair, Hobson steamed all the way to Norfolk, via a number of interim stops, arriving on 15 June 1945. Hobson was still under repair when the war ended.

Commander Manning was awarded a Navy Cross for fighting and saving his ship. The ship’s engineer officer, Lieutenant (j.g.) Martin J. Cavanaugh Jr., and Chief Machinist’s Mate Howard B. Farris were awarded the Silver Star. The ship’s executive officer, Lieutenant Robert Vogel, was awarded a Bronze Star. Hobson would be awarded six battle stars for its World War II service to go with the Presidential Unit Citation.

Unlike many such damaged ships that were scrapped or put in reserve at war’s end, Hobson’s repairs were completed and the ship remained in service after the war. Hobson’s routine consisted of minesweeping and amphibious exercises along the East Coast until that fateful night in April 1952.

In 1954, the USS Hobson Memorial Society erected an obelisk of pink granite on the bank of the Cooper River in Charleston, South Carolina, with names engraved of the Sailors lost with the sinking of Hobson. Around the obelisk are 38 stones representing the 38 states that were home to the 176 Sailors who perished.

(Sources: NHHC Dictionary of American Fighting Ships [DANFS]; Judge Advocate General’s Corps, U.S. Navy, Findings of U.S. Navy, Court of Inquiry into Collision of USS Hobson and USS Wasp; Michael Junge,“A Tradition Older,” Real Clear Defense, 19 February 2019.)