H-Gram 055: The 70th Anniversary of the Korean War (Wonsan: October─November 1950), the 30th Anniversary of Desert Shield/Desert Storm (Part 4: November 1990), and the 20th Anniversary of the Attack on USS Cole (DDG-67)

8 October 2020

Korean War Minesweeping. Four U.S. Navy minesweepers (AMS) tied up at Yokosuka, Japan, following mine clearance activities off Korea. Original photo is dated 30 November 1950. These four ships, all units of Mine Division 31, are (from left to right): USS Merganser (AMS-26); USS Osprey (AMS-28); USS Chatterer (AMS-40) and USS Mockingbird (AMS-27). Ship in the extreme left background is USS Wantuck (APD-125). Official U.S. Navy Photograph, now in the collections of the National Archives. (80-G-424597)

Contents

- 70th Anniversary of the Korean War

- 30th Anniversary of Desert Shield/Desert Storm–October 1990.

- 20th Anniversary of the Attack on USS Cole (DDG-67)

Download a PDF of H-Gram 055 (6.1 MB)

This H-Gram focuses on the successful USMC/USN amphibious landings at the port of Wonsan on the east coast of North Korea on 26 October 1950, with continuing damage and loss to U.S. ships due to extensive North Korean minelaying preceding the landing. This H-Gram also covers U.S. Navy operations during Desert Shield in November 1990, particularly the provocative Iraqi Mirage F-1 flights in the Arabian Gulf. Also covered is the October 2000 terrorist attack on USS Cole (DDG-67).

70th Anniversary of the Korean War

“We have lost control of the seas to a nation without a Navy, using pre-World War I weapons, laid by vessels that were utilized at the time of the birth of Christ.” ─ Rear Admiral Allen E. “Hoke” Smith (CTF-95) at Wonsan.

RADM Smith sent this message after two of the three operational steel-hulled minesweepers (Pirate (AM-275) and Pledge (AM-277)) in the U.S. Navy struck mines, blew up, and sank in quick succession with the loss of 13 crewmen, while trying to clear a path into the North Korean port of Wonsan, on the Sea of Japan, on 12 October 1950. Previously undetected North Korean shore batteries then fired on the sinking minesweepers and survivors in the water. The third minesweeper (Incredible (AM-249)) was disabled in the action. The surviving wooden-hulled small minesweepers (AMS-type) then had the arduous task of clearing a path through over 3,000 Soviet mines laid by the North Koreans off Wonsan (for which the commander of Mine Division 31, Lieutenant Commander D’arcy Shouldice, would be awarded a Navy Cross,and which would delay the landing of over 50,000 troops of X Corps (1st Marine Division and 7th Infantry Division) from 20 October to 26 October (even though Wonsan had been in the hands of South Korean troops since 10 October).

The threat was actually far more sophisticated than RADM Smith’s message suggested, as Soviet Navy advisors provided over 4,000 mines to the North Koreans. Most of the mines were moored contact mines based on designs from the 1905 Russo-Japanese War (which worked just fine) but also included sophisticated bottom influence “magnetic” mines, sensitive enough to react to a wooden minesweepers engines. The Soviet advisors assembled the mines, trained the North Koreans, planned the minefields, and supervised the minelaying operations, including providing Russian navigators to the civilian craft pressed into service as minelayers. When the North Koreans withdrew in advance of the South Korean offensive, they executed any of the civilian crewmen who had knowledge of the minefield locations.

Wonsan Landing, October 1950. LVTs, LCVPs, and an LCM beaching on the Kalmo Pando, at Wonsan, North Korea, to land elements of the First Marine Division, 26 October 1950. The LCM at left appears to be from USS Union (AKA-106). Official U.S. Navy Photograph, from the collections of the Naval History and Heritage Command. (NH 96881)

Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Forrest Sherman was perhaps even more blunt than RADM Smith, stating that the mining of Wonsan, “caught us with our pants down.”

Following the landings at Inchon on 15 September 1950, the recapture of Seoul, and the breakout from the Pusan Perimeter, senior U.S. and United Nations leaders debated whether to cross the former demarcation line at the 38th Parallel into North Korea. The Republic of Korea (ROK) Army just kept on going as the decimated North Korean army offered little resistance. The UN commander in Korea, General of the Army Douglas MacArthur, decided to continue the attack across the 38th Parallel to complete the destruction of the North Korean army and force North Korea to surrender.

MacArthur’s plan called for the U.S. Eighth Army to cross the border north of Seoul and advance on the North Korean capital of Pyongyang. In the meantime, X Corps, which had conducted the Inchon landings and recapture of Seoul, would re-embark on ships, sail around the Korean Peninsula, and conduct an amphibious assault on the east coast of North Korea at Wonsan (Operation Tailboard). However, the route of the North Korean Army was so complete that ROK troops advancing up the east coast were in Wonsan ten days before the scheduled amphibious assault, which was therefore changed from an assault to an administrative landing. However, although the North Koreans had withdrawn, the mines kept fighting.

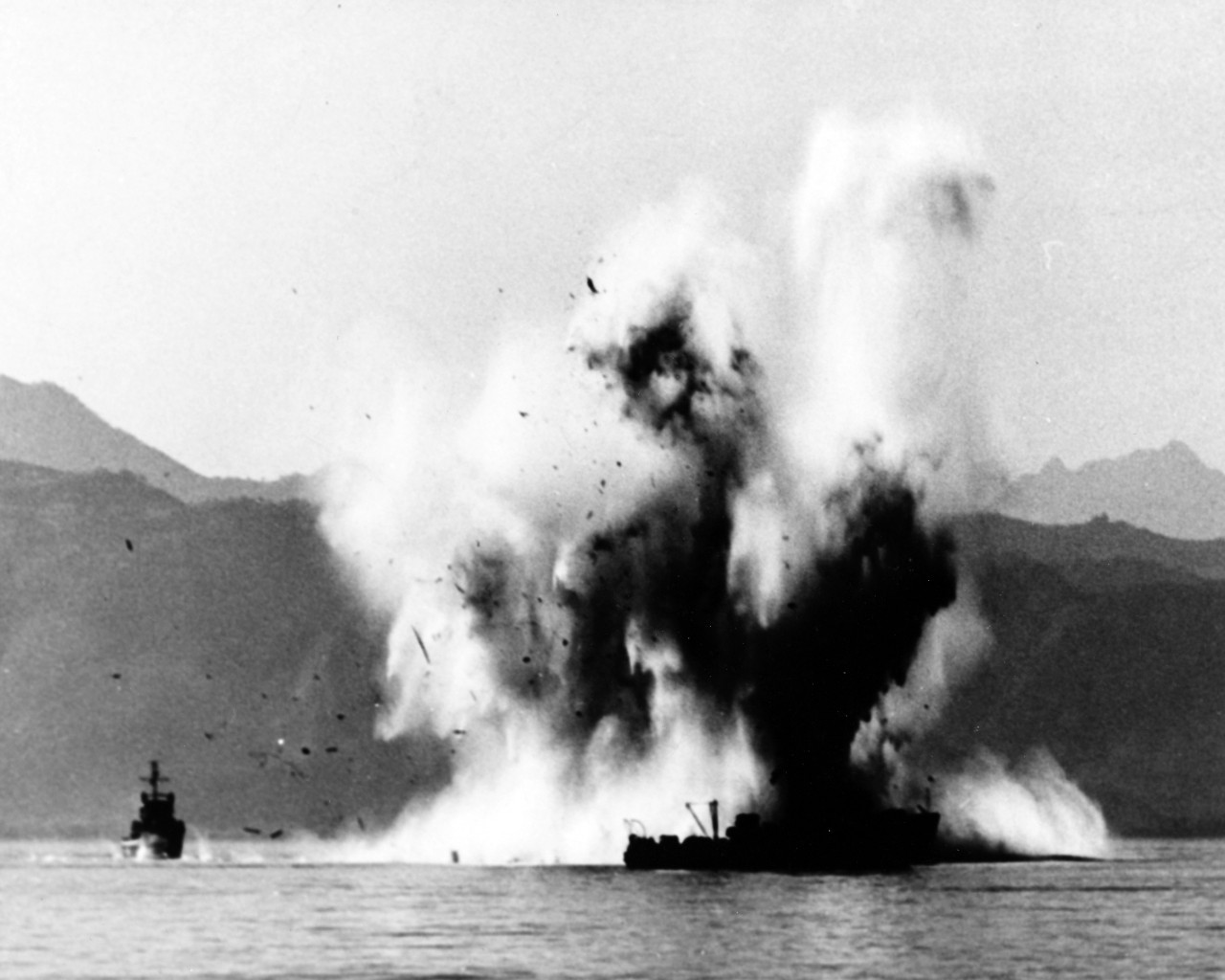

Republic of Korea minesweeper YMS-516 is blown up by a magnetic mine, during sweeping operations west of Kalma Pando, Wonsan harbor, on 18 October 1950. This ship was originally the U.S. Navy's YMS-148, which had served in the British Navy in 1943-46. Official U.S. Navy Photograph, now in the collections of the National Archives. (80-G-423625)

After the 12 October action, the mines would sink a ROK Navy minesweeper and a Japanese contract minesweeper, before a path was finally clear. As over 50,000 U.S. troops were getting seasick and dysentery during what became known as “Operation Yo-Yo,” the surviving small minesweepers worked feverishly to clear the path, made more difficult by the discovery of the magnetic mines on 18 October. It took so long for the Marines on the ships (who went in first) to get ashore that they were met at the beach by Bob Hope and a USO troupe.

The good news from the Wonsan operations was that, except for the minesweepers (and dysentery), there were no casualties amongst the landing forces. The bad news was that although ten days had been allotted to sweep mines, it actually took 16. A subsequent opening of the west coast port of Chinnampo was also delayed due to the need to sweep large numbers of mines, which slowed the Eighth Army’s offensive. An impact of the delays was that U.S. Army and Marine forces were still advancing (i.e., not in prepared defensive positions) when the massive Communist Chinese counter-offensive occurred in November, with yet another disastrous reversal for UN troops in Korea (which will be covered in the next H-Gram).

For more on the operations as Wonsan and Chinnampo, please see attachment H-055-1. For background on the Korean War and operations from 25 June to 10 October 1950 please see H-Grams 050 and 054.

A Sailor stands watch at the bow of a ship on patrol in the Gulf during Operation Desert Shield/Operation Desert Storm. (National Archives photo)

30th Anniversary of Operation Desert Shield and Desert Storm, November 1990

On 8 November 1990, Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney announced that in addition to the 230,000 U.S. forces that had arrived or were already en route to Saudi Arabia, additional U.S. heavy divisions, Marines, and ships would deploy to the region, including three more aircraft carriers, another battleship, another amphibious group, and the maritime pre-position ship squadron from Norfolk. The next week, Secretary Cheney announced the activation of 72,500 more reservists to support Operation Desert Shield. Additional reserve forces would be called up over the next month, including 30 naval reserve units from 13 states and Washington, D.C., and reserve call-ups were extended from 90 to 180 days.

By the beginning of November, three U.S. Navy aircraft carriers were operating in the region. USS Dwight D. Eisenhower (CVN-69) had returned to the U.S. after being relieved in the Red Sea by USS Saratoga (CV-60) and USS John F. Kennedy (CV-67), which were alternating between the Red Sea and the Eastern Mediterranean (Saratoga would set a record for Suez Canal transits on a single deployment). In the Arabian Sea, USS Midway (CV-41) had deployed from Japan and relieved USS Independence (CV-62) on 1 November and Independence returned to the U.S. west coast. Although not publically named in the initial announcement, the carriers USS America (CV-66) and USS Theodore Roosevelt (CVN-71) would deploy from Norfolk and USS Ranger (CV-61) would deploy from San Diego to arrive in the region by mid-January 1991, giving six aircraft carriers to support any offensive operations. The battleship Missouri (BB-63) deployed from Long Beach on 13 November to join the battleship Wisconsin (BB-64), already operating in the Arabian Gulf. The 13-ship Amphibious Group THREE, with the 5th Marine Expeditionary Brigade embarked, would depart San Diego on 1 December 1990.

Maritime Interception Operations in support of UN sanctions continued at an intense pace, aided by a growing armada of allied and coalition ships, some from countries that were not willing to contribute ground troops to possible war against Iraq but were perfectly happy to contribute ships to a UN effort, an operation that was greatly aided by the long history of U.S. Navy forward engagement and exercises with these countries. By the end of November, 4,217 merchant ships had been intercepted and challenged, 517 ships boarded, and 19 ships diverted due to carrying prohibited cargo. On 26 November 1990, the Iraqi-flagged merchant ship Khawla Bint Az Zawra was intercepted by USS Philippine Sea (CG-58) and USS Thomas C. Hart (FF-1092) and two multinational ships, but refused repeated orders to stop until Philippine Sea fired warning shots. After being boarded and found not to be carrying prohibited cargo, the Iraqi ship was allowed to proceed into Aqaba, Jordan.

Between 15-21 November, 16 U.S. ships and 1,000 Marines conducted a highly publicized joint/combined exercise, Imminent Thunder, practicing an amphibious assault on the coast of Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province, intended to ratchet up the pressure on Iraq to withdraw from Kuwait. (I will cover the planning for amphibious assault operations, the deception plan, and Iraqi minewarfare developments in a comprehensive fashion in the January and February 1991 installments of this series).

Also in November, Iraqi Mirage F-1 fighters armed with Exocet anti-ship missiles commenced provocative ship attack profiles down the Arabian Gulf, turning around just at an arbitrary line drawn across the Arabian Gulf by CENTCOM, north of which U.S. Navy air and surface forces were forbidden to cross. The line was completely ineffective in reducing the possibility of an inadvertent clash between the U.S. Navy and Iraq (before the rest of CENTCOM’s forces were ready for war) but did provide Iraq a sanctuary to lay large numbers of mines and conduct other unobserved operations in international waters in violation of international law, which would have potentially severe consequences later.

On 29 November 1990, the United Nations Security Council approved a resolution authorizing the use of force unless Iraqi forces vacated Kuwait by 15 January 1991. For more on Desert Shield/Desert Storm–November 1990 please see attachment H-055-2.

Members of a Navy honor guard from the guided-missile destroyer USS Cole practice rendering colors before a memorial service at the USS Cole Memorial at Naval Station Norfolk. The Norfolk-based ship was damaged by a suicide bombing while refueling in the Port of Aden in Yemen, killing 17 and wounding 39 Sailors. (Photo by Petty Officer 1st Class Julie Matyascik)

20th Anniversary of the Attack on USS Cole (DDG-67)

At about 1118 local time on 12 October 2000, two men in a 35-foot fiberglass boat approached USS Cole (DDG-67) in an unassuming manner, smiling and waving, while Cole was refueling in the harbor of Aden at Refueling Dolphin Seven, reachable only by boat. As the boat pulled alongside, a massive explosion from a probable shaped charge blew a 30- by 40-foot hole, extending 16 feet below the waterline, portside amidships, entering a machinery space and violently pushing the deck of the galley upward, killing many Sailors as they were waiting for chow. As a result of the explosion, 17 Sailors were killed and 37 wounded. Despite the severity of the blast, the keel was not broken and the ship remained afloat, although strenuous and extended damage control efforts over several days were necessary to keep the ship from settling. On 29 October, Cole was underway from Aden with her battle ensign flying, to be loaded aboard the semi-submersible heavy-lift ship M/V Blue Marlin (out of sight of shore). After repairs, Cole returned to active service in April 2002 and deployed again in November 2003, and continues to serve in the fleet today.

The terrorist group al-Qaida, led by Osama bin Laden, quickly claimed credit for the attack, and there was plenty of evidence that they did it. The post attack investigation also revealed that al-Qaida had attempted to attack USS The Sullivans (DDG-68) in Aden on 3 January 2000, but the attempt failed when the overloaded suicide boat stuck in the mud. The attack on the Cole provided warning of what was to come, had it been heeded.

For more on the USS Cole attack, please see attachment H-055-3.