H-055-1: Wonsan: October─November 1950

H-Gram 055, Attachment 1

Samuel J. Cox, Director NHHC

October 2020

Planning for Wonsan Landings

With the success of the Inchon landings on 15 September 1950, the subsequent recapture of Seoul, the breakout of UN forces (U.S. Eighth Army and Republic of Korea (ROK) Army) from the Pusan Perimeter, and the collapse of decimated North Korean forces in the south, the strategic situation on the Korean Peninsula on 1 October 1950 was dramatically altered from only one month earlier when North Korean forces were still attacking the Pusan Perimeter. U.S. Commanders were then faced with the classic military question, “and then what?”.

The two basic options for concluding the war were to restore the status quo from before the war with North and South Korea at the 38th Parallel, or to continue offensive operations into North Korea to complete the destruction of the North Korean army. The first option still left a significant number of North Korean forces intact to cause trouble later. The second option carried risk of intervention by Communist Chinese or Soviet forces, or even worse, that the war might expand to Europe or even into a global conflict. Since the Soviets had produced their own atomic bomb in 1949, the risk of expanded conflict was profound.

Concern that the Soviets were using the conflict in Korea to bog down the U.S. as a diversion before a major assault on western Europe drove policymaking at the senior levels of U.S. political and military leadership, and was the basis for conducting a “limited” war in Korea, much to the consternation of military leaders in Korea who had to fight it. As an example, the three newest and most-capable U.S. aircraft carriers (Midway (CV-41),, Franklin Roosevelt (CV-42), and Coral Sea (CV-43)) never served in Korea, being held instead in the Atlantic and Mediterranean to guard against a Soviet attack in Europe).

At the August 1950 summit meeting between General of the Army Douglas MacArthur, the Chief of Naval Operations, and the Army Chief of Staff (that led to the decision to go ahead with the Inchon landing plan), there was agreement that the aim of pursuing the destruction of North Korean forces was not necessarily limited to south of the 38th Parallel. In mid-September, the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) gave permission to General MacArthur to plan ground operations north of the 38th Parallel (air strike and naval bombardments had been going on north of the 38th Parallel since the very beginning of the war). On 27 September, the JCS authorized ground operations north of the 38th Parallel to complete the destruction of the North Korean army, with the caveat that no major Chinese or Soviet forces were present. In no case were U.S. forces to violate the Chinese or Soviet border and only Republic of Korea (ROK) forces were to be permitted to operate in the border areas. ROK President Syngman Rhee had already made clear his intent, now that ROK forces were on a roll, to continue the attack into North Korea with or without the UN or the U.S.

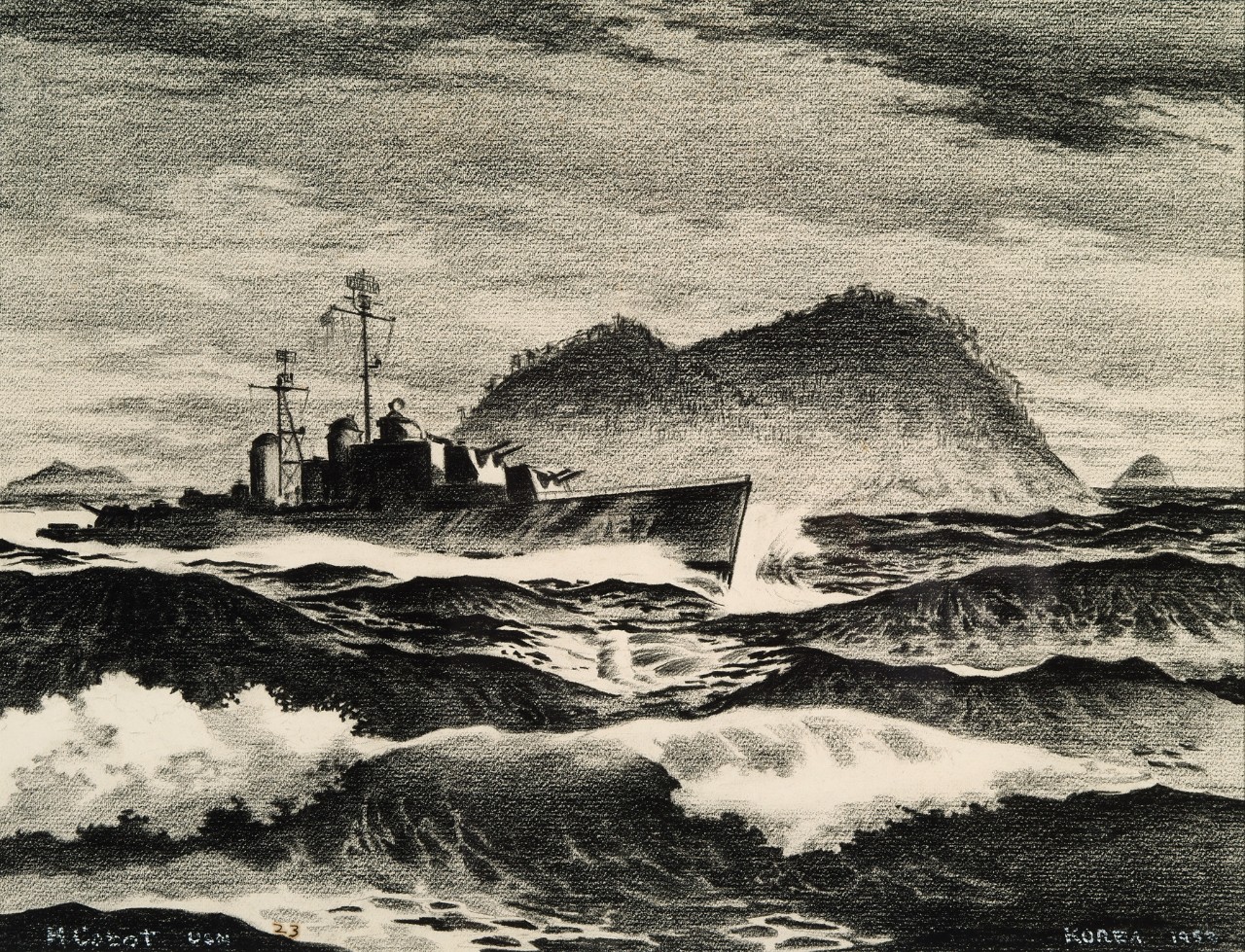

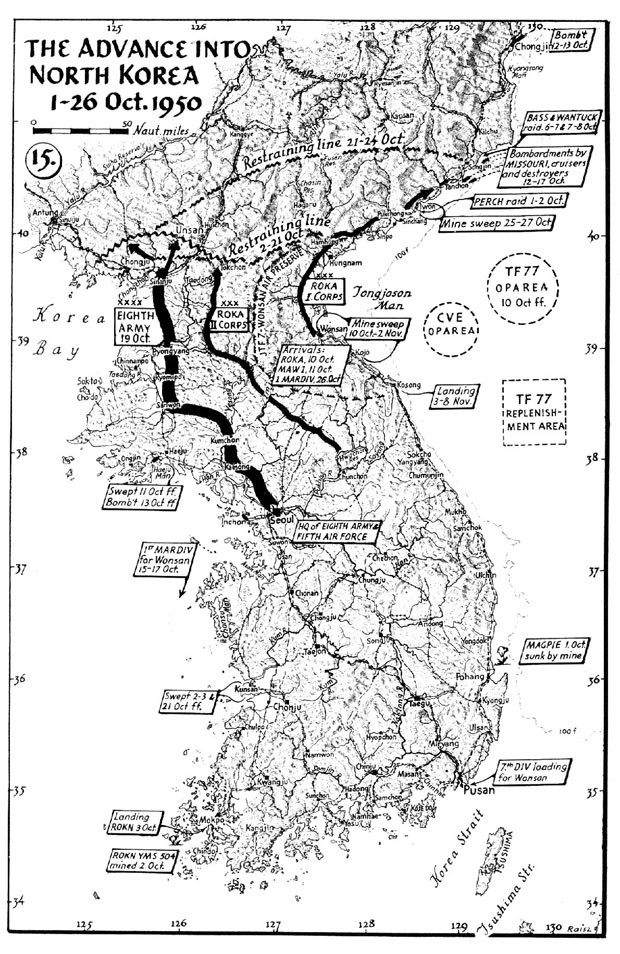

The Advance into North Korea, 1–26 October 1950. (from History of United States Naval Operations: Korea)

On 26 September, MacArthur directed planning for an Inchon-scale amphibious assault to take place on the east coast of North Korea at Wonsan, designated Operation Tailboard. The plan called for the U.S. Eighth Army to commence an assault in mid-October from Seoul into North Korea with the intent to take the capital of Pyongyang. The X Corps (1st Marine Division and 7th U.S. Army Infantry Division, which had conducted the Inchon landing and recapture of Seoul) would be extracted from ongoing operations to be re-embarked on Joint Task Force Seven (JTF 7) ships, transported around the Korean peninsula, to conduct an amphibious assault at Wonsan with D-Day set for 20 October 1950. Once ashore, the plan called for X Corps to attack westward and link up with Eighth Army to complete the encirclement and destruction of North Korean forces.

The logistics challenges of extracting X Corps from the Seoul/Inchon area, while simultaneously sustaining an offensive by Eighth Army into North Korea and the reintroduction of U.S. air forces back into South Korea, via the limited South Korean port facilities (not to mention all the blasted bridges and transportation infrastructure), were immense. Because of the daunting logistics issues, the commander of U.S. Naval Forces Far East (COMNAVFE), Vice Admiral C. Turner Joy, opposed the Wonsan operation, as did some senior Army officers who thought it would be easier to attack overland the 115 miles from Seoul to Wonsan. Nevertheless, General MacArthur remained insistent on the Wonsan operation, and on 28 September the plan was sent to the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS), which approved it in short order, adding a restraining line at the 40th Parallel, north of which only ROK forces could go.

In the hangover after the 29 September liberation ceremonies in Seoul, a statement by Communist Chinese Foreign Minister Chou En-lai the next day was, in hindsight, not taken seriously enough. Chou stated that the Chinese would not tolerate foreign forces crossing the 38th Parallel. At the time, the bulk of the Communist Chinese army was arrayed along the Taiwan Strait in what appeared to be preparations to invade the Nationalist Chinese refuge on Taiwan. There was far more concern in Washington, D.C. that the Chinese would invade Taiwan than there was about whether the Chinese had meant what they said about North Korea. Despite this, the UN General Assembly (Communist China was not a member) went ahead and approved “all appropriate steps” to be taken to ensure stability in Korea, a somewhat vague direction interpreted as authorization for U.N. forces to operate north of the 38th Parallel. On 9 October, the JCS went so far as to authorize attacks against small-scale Chinese or Soviet forces inside North Korea, if encountered, so long as success was likely. The border, however, remained inviolate, which the Communists would use to their advantage for the rest of the war.

In preparation for the Wonsan assault, Joint Task Force Seven (JTF 7) was re-formed, with Vice Admiral Arthur D. Struble in command again. The plan was very similar to that of Inchon, with the arrival of the amphibious attack force to be preceded by patrol and reconnaissance aircraft, strikes by Task Force 77 carrier aircraft, naval gunfire, and minesweeping operations. JTF 7 would provide its own air support and have its own operating area, free of “interference” by the U.S. Air Force.

The task organization for Operation Tailboard, the amphibious assault on Wonsan, North Korea, was also very similar to that of the Inchon landings. The commander of U.S. Seventh Fleet, VADM Struble, was once again the commander of Joint Task Force Seven (JTF 7), this time embarked on battleship Missouri (BB-63). The mission of JTF 7 was to put ashore the X Corps, still under the command of U.S. Army Major General Edward Almond, which included the 1st Marine Division, under the command of U.S. Marine Major General Oliver P. Smith and the U.S. Army 7th Infantry Division.

The Advance Force (Task Force 95) would lead the way in the attack and was commanded by Rear Admiral Allen E. Smith, embarked on light cruiser Worcester (CL-144). TF 95 included Task Group 95.2 (TG 95.2), the Covering and Support Group, under the command of Rear Admiral Charles C. Hartman, embarked on heavy cruiser Helena (CA-75). TG 95.2 included three heavy cruisers (Rochester (CA-124), Helena (CA-75), Toledo (CA-133)), one British light cruiser (HMS Ceylon), and six destroyers (three U.S., one British, one Australian, and one Canadian).

TG 95.2, the Minesweeping Group, commanded by Captain Richard T. Spofford, included one destroyer (Collett (DD-730), one fast-transport (APD), two destroyer-minesweepers, three minesweepers (AM-steel hull), seven small minesweepers (AMS – wood hull), one repair ship (internal combustion engine)(ARG), one salvage ship (ARS), and eight Japanese contract minesweepers (JMS). Three ROKN auxiliary motor minesweepers (YMS) would subsequently join.

TG 96.2, the Patrol and Reconnaissance Group, commanded by Rear Admiral George R. Henderson, included one seaplane tender (AV), one small seaplane tender (AVP), three U.S. Navy and one Royal Navy patrol squadrons.

TG 96.8, the Escort Carrier Group, commanded by Rear Admiral Richard W. Ruble, included two escort carriers (Sicily (CVE-118) and Badoeng Strait (CVE-116)), with embarked Marine fighter-bomber squadrons, and six destroyers.

Task Force 77, the Fast Carrier Force, commanded by Rear Admiral Edward C. Ewen, included four carriers (Valley Forge (CV-45), Philippine Sea (CV-47), Boxer (CV-21), Leyte (CV-32)), one battleship (Missouri (BB-63)), one light cruiser (Manchester (CL-83)), and 16 destroyers. This was the first time four Essex-class carriers operated together since World War II.

Task Force 79, the Logistic Support Forces, commanded by Captain B. L. Austin, included units assigned from Service Squadron 3 and Service Division 31.

Task Force 90, the Attack Forces, was commanded by Rear Admiral James H. Doyle, embarked in Mount Mckinley (AGC-7), with Commander X Corps and Commander 1st Marine Division also embarked. TF 90 included two amphibious command ships (AGC), two high-speed troop transports (APD), four patrol frigates (PF─one British, two New Zealand, and one French), one patrol escort, control (PCEC), nine attack personnel transports (APA), 15 civilian-manned personnel transports (T-AP), ten attack cargo ships (AKA), five dock landing ships (LSD), three “rocket ships” (LSMR), 48 tank landing ships (LST), including 30 Japanese-manned (Scajap) LSTs), 20 utility landing ships, and additional Military Sea Transport Service (MSTS) shipping.

As the forces for the Wonsan operation were assembling, and overcoming numerous logistics hurdles, the ROK Army 1st Corps was advancing so fast up the east coast route that it appeared likely they would be in Wonsan well before the amphibious assault. (The remaining North Korean forces in the east had taken to the hills and were not seriously contesting the ROK advance). Consideration was given to having the 1st Marine Division assault Hungnam (50 miles north of Wonsan) while the 7th Infantry Division would administratively land at Wonsan, as they had at Inchon. VADM Struble ultimately vetoed the idea due to logistics complications, but a major factor was an insufficient number of minesweepers to support landings in two different locations. On 10 October, JTF 7 issued orders reconfirming that all Operation Tailboard forces would land at Wonsan.

Preliminary Raids, Movements for Wonsan, and Minesweeper Status, 6-10 October 1950

The Wonsan operation was preceded by two night raids on the North Korean coast railroad between Wonsan and Vladivostok, executed by British Royal Marine Commandos embarked on U.S. fast transports Horace A. Bass (APD-125) and Wantuck (APD-125), supported by destroyer De Haven (DD-727). On the night of 6-7 October, British commandoes blew the railway tunnel at Kyongsong Man, less than 20 miles south Chongjin. The second raid targeted a railroad tunnel and bridge a few miles south of Songjin. Both operations were deemed successful.

Commencing 6 October 1950, JTF 7 forces began transit toward Wonsan, with the slower units getting underway first, including the minesweepers of TG 95.6, from Sasebo, Japan. On 8 October PBM Mariner flying boats shifted patrol operations from the Yellow Sea to the east coast of North Korea, with a focus on locating minefields. On 9 October, carriers Leyte (just arrived from the Atlantic on 8 October) and Philippine Sea departed Sasebo, in company with light cruise Manchester and eleven destroyers. The next day, heavy cruiser Helena (with RADM Hartman embarked) in company with light cruiser Worcester (with RADM Allen Smith embarked) and British light cruiser HMS Ceylon departed Sasebo. On 11 October, VADM Struble, embarked in battleship Missouri got underway from Sasebo in company with carrier Valley Forge (CV-45) and a screen of destroyers.

On 10 October 1950, the Minesweeping Force (TG 95.6) commenced operations in the approaches to Wonsan. The same day ROK forces entered Wonsan and captured the airfield, which would be operating U.S. Marine squadrons by 14 October. The capture of Wonsan by the South Koreans eliminated most resistance with the good news that a combat amphibious assault, still scheduled for 20 October, would not be necessary. However, the North Korean mines didn’t get the word.

Mine warfare had not been all that significant a factor in the Pacific War, although the minefields laid in Japanese home waters late in the war by B-29 bombers (using U.S. Navy mines) were highly effective. It was a different story in European waters, especially in naval operations in the Baltic and Black Seas between the Soviets and Nazi Germany. During the Russo Japanese War in 1904−1905, Russian mines sank two Japanese battleships, three cruisers, and four other ships, about the Russian’s only successes in an otherwise dismal performance against the upstart Japanese navy. The effectiveness of mines was not lost on the Russians, who proceeded to refine doctrine and tactics and stockpile large numbers of mines. The great majority of Soviet mines in use by 1950 were moored contact-mines based on designs from the Russo-Japanese War, in keeping with the Russian philosophy of “better is the enemy of good enough.” The old designs worked just fine (including in Iranian hands in the 1980s). Nevertheless, the Soviets also developed relatively sophisticated bottom influence (“magnetic”) mines as well. (See H-Gram 053 for a more detailed description of Soviet mines used during the Korean War).

In keeping with their emphasis on mine warfare, the Soviets also maintained a fairly large minesweeper force. Of 213 minesweepers in Asian countries in 1950, almost half belonged to the Soviet Pacific fleet, including 50 ex-U.S. motor minesweepers provided late in World War II under U.S./Soviet Lend-lease (Project Hula). Even though the Soviet Union was a member of the United Nations, these minesweepers would of course be of no use to the UN forces in Korea. The U.S. Navy, on the other hand, had close to nothing in the way of minesweepers at the start of the war. In typical U.S. fashion, in the precipitous drawdown at the end of World War II, the extensive U.S. minesweeping forces were among the first to go to the scrapyard or to mothballs. Draconian budget cuts made it even worse, and in 1948 even the Mine Warfare Type Command was dissolved. There wasn’t even a degaussing range west of Pearl Harbor.

Mine Division Thirty-One. (Complete Caption) Commanding Officers in conference off Korea, 26 October 1950. Probably taken in the wardroom of USS Incredible (AM-249) during minesweeping operations off Wonsan. Those present are (from left to right): Lieutenant Edward P. Flynn, Commanding Officer of USS Incredible; Lieutenant (Junior Grade) Nicholas Grkovic, CO of USS Kite (AMS-22); Lieutenant (Junior Grade) Robert C. Fuller, CO of USS Partridge (AMS-31); Lieutenant Commander D'Arcy V. Shouldice, Commander, Mine Division 31; Lieutenant (Junior Grade) T.R. Howard, CO of USS Redhead (AMS-34); Lieutenant (Junior Grade) James P. McMahon, CO of USS Chatterer (AMS-40); Lieutenant (Junior Grade) Philip Levin, CO of USS Osprey (AMS-28) and Lieutenant (Junior Grade) Stanley P. Gary, CO of USS Mockingbird (AMS-27). Note medical operating table lamp overhead and extensive consumption of cigarettes and coffee. Official U.S. Navy Photograph, now in the collections of the National Archives.

Upon the outbreak of the Korean War, the entire minesweeping force of Naval Forces Far East (COMNAVFE) consisted of ten minesweepers of Mine Squadron Three (MINRON 3), commanded by Lieutenant Commander D’arcy Shouldice. Mine Division Thirty-Two (MINDIV 32) included four steel-hulled large minesweepers (AM-type), only one of which was in commission and the other three in reserve. Mine Division Thirty-One (MINDIV 31) included six wooden hulled small minesweepers (AMS-type). By mid-August, two of the reserve minesweepers, Pirate (AM-275) and Incredible (AM-249), had been reactivated, but Mainstay (AM-261) was still “down for parts.” There were a dozen more minesweepers in the Pacific; two at Guam and the rest spread between Pearl Harbor and West Coast ports.

The first reinforcement to COMNAVFE’s minesweeping force was the arrival of destroyer-minesweepers Endicott (DMS-35) and Doyle (DMS-34) in late July. However as the extent of the mine threat did not become apparent until late September, the two ships were diverted to typical destroyer duties. In August 1950, COMNAVFE, VADM Turner Joy, asked for more minesweepers, which was denied as the activation of other types of ships from mothballs had higher priority. The discovery of North Korean mines in mid-October changed the prevailing lethargy regarding minesweepers. On 16 September, Magpie (AMS-25) and Merganser (AMS-26) were sent forward from Guam and three more AMSs of MINDIV 51 were sent forward from Pearl Harbor, and the Chief of Naval Operations revised the reactivation schedule to include nine AMSs. On 1 October, Magpie struck a mine and sank with 21 of her crew of 22. On 2 October, the only two other destroyer-minesweepers in the Pacific, Thompson (DMS-38) and Carmick (DMS-33) were ordered forward from the West Coast as were the three remaining AMSs of MINDIV 51.

Opening of Wonsan, October 1950. USS Merganser (AMS-26) tied up to USS Conserver (ARS-39) in Wonsan Harbor, Korea. Photographed by AFAN W.C. Newbill. The original photo is dated 23 October 1950. Note navigation bouy on Conserver's after deck and ships in background, including another AMS and a high-speed minesweeper (DMS). Official U.S. Navy Photograph, now in the collections of the National Archives. (80-G-422161)

VADM Joy was able to get permission from General MacArthur (who still retained his hat as Supreme Commander Allied Powers Japan (SCAP)) to employ 20 contract Japanese minesweepers (JMS). The Deputy Chief of Staff of CMNAVFE, RADM Arleigh Burke, was the point man for gaining use of the Japanese vessels. Japanese minesweepers were the most experienced in the world at clearing bottom influence mines, having cleared over 900 such mines from Japanese waters after World War II laid by the U.S. during “Operation Starvation”(see H-gram 053). These vessels were initially intended only to operate in non-combat conditions south of the 38th Parallel (and the crews were given double pay). However, the need for minesweepers would prove so acute that the Japanese vessels were quickly pressed into service north of the Parallel. Ultimately, the Japanese would contribute 43 contract minesweepers, ten patrol boats, and one trial ship (Soei Maru) to the Korean War, with a total of about 1,200 Japanese personnel. The purpose of the “trial ship” was to steam through swept areas to test that it was safe to do so. Not surprisingly, it proved hard to recruit crewmen for the trial ship. The use of Japanese vessels in a combat zone was also extremely politically sensitive in Japan.

Because the North Koreans only belatedly realized that Inchon would be the location of the major UN amphibious landing, their minelaying activity was too little, too late. U.S. minesweepers were not over-taxed at Inchon, although minesweeper Pledge (AM-277) did capture 44 enemy prisoners aboard a sampan while operating in the vicinity of Inchon. By late September, the mine threat at Inchon had been dealt with, and the minesweepers began transiting to the east coast of Korea.

After departing Inchon, Pledge, Mockingbird (AMS-27), Chatterer (AMS-40), Kite (AMS-22), and Redhead (AMS-34) conducted minesweeping at the port of Kunsan on the southwest coast of South Korea. Kunsan had been more extensively mined than Inchon as the North Koreans assumed it was a more likely place for a landing than Inchon. On 2 and 3 October, the minesweepers cleared a 22-mile-long, 1,500-yard channel. Seven moored contact mines were swept and destroyed and another 49 located and marked. The minesweepers then headed for Wonsan, where they would find a far greater challenge.

Soviet Navy officers had been in Wonsan as late as 5 October, running a mine school for the North Koreans, assembling magnetic bottom influence mines (sensitive enough to be triggered by a wooden minesweeper hull), planning the minefields, and supervising the seeding of the minefields. The North Koreans used sampans to tow barges and rolled mines off the stern in a fairly precise manner. Of about 4,000 mines provided by the Soviets, over 3,000 were employed at Wonsan and hundreds at a variety of other locations, including some planted in waters in South Korea. When the North Koreans pulled out of Wonsan, they executed the civilian crews of the sampans who knew where the minefields were laid.

Wonsan is located at the westernmost point of the Sea of Japan. It is situated on the southwest side of a bay shaped like a lopsided semicircle oriented northwest-southeast. In the center of the approach to the bay is Yo Do Island (actually “island” is redundant) with a smaller island to the north, Ung Do. There are several smaller islands in the bay past Yo Do, before reaching Wonsan. The most direct passage from the sea to Wonsan passes to the south of Yo Do. A bit longer route passes between Yo Do and Ung Do and was known as the “Russian Route” as it had previously been used by Soviet ships entering and leaving Wonsan before the war started. The daily tidal variation at Wonsan is only one foot (compared to 30 feet at Inchon), but it is still 30 miles from the 100-fathom line to the port.

The original COMNAVFE plan recognized the strong probability the Wonsan would be mined, and initially called for minesweeping to commence at D minus 5 (five days before the assault planned for 20 October). However, given the paucity of sweepers and the length of the channel that needed to be swept, COMNAVFE adjusted the plan to allow for ten days of minesweeping before the assault. This would not be enough.

10 October 1950, Wonsan Operation Commences

Task Group TG 95.6., the Minesweeping Group that was commanded by Captain Richard T. Spofford, embarked on destroyer Collett. CAPT Spofford had replaced LCDR Shouldice as commander of Mine Squadron Three and Shouldice had then assumed command of Mine Division 31. The fast transport Diachenko (APD-123) served as mother ship for an underwater demolition team. The group included three “steel” minesweepers, Pirate, Pledge, and Incredible, and seven smaller U.S. “wooden” minesweepers (AMS). There were also three ROKN auxiliary motor minesweepers (YMS). Eight Japanese contract minesweepers (JMS), under the command of Captain Tamura, were also part of the effort. The combustion engine repair ship Kermit Roosevelt (ARG-16) and a salvage ship rounded out the group.

Fire support to TG 95.6 was provided by heavy cruiser Rochester, with RADM John Higgins (Commander, Cruiser Division Five) and a helicopter embarked, and several destroyers. Fast Carrier Force (TF 77) aircraft provide Combat Air Patrol (CAP) and air support. PBM Mariner flying boats provided search support, and their on-station time was about to be significantly increased by the establishment of a seadrome at Chinhae by small seaplane tender Gardiners Bay (AVP-39).

Minesweeping operations for Wonsan commenced at dawn on 10 October 1950. Pledge led Incredible, Mockingbird, and Osprey (AMS-28) in sweeping a channel 3,000 yards wide on the direct route to Wonsan to the south of Yo Do, with the helicopter from Rochester scouting ahead (one account says the helicopter was from light cruiser Worcester). Chatterer trailed behind to mark the channel, while Partridge (AMS-31) destroyed mines that came to the surface with gunfire. As the sweep operation continued, aircraft from Leyte and Philippine Sea bombed suspected defenses on islands in the bay.

As sunset approached, ten miles of channel had been swept (to the 30 fathom line) and 18 moored contact mines destroyed (some accounts say 21 mines accounted for). At that point, the helicopter reported first one mine line, then two, and then five mine lines ahead. As a result of the heavy minefields on the direct route, CAPT Spofford opted to abandon the direct route and shift operations to the longer (34 NM) “Russian Route” to the north of Yo Do in hopes of finding less dense minefields. (The use of a helicopter to scout for mines was a new innovation, although it was hampered by having to relay all communications through the destroyer-minesweeper Endicott).

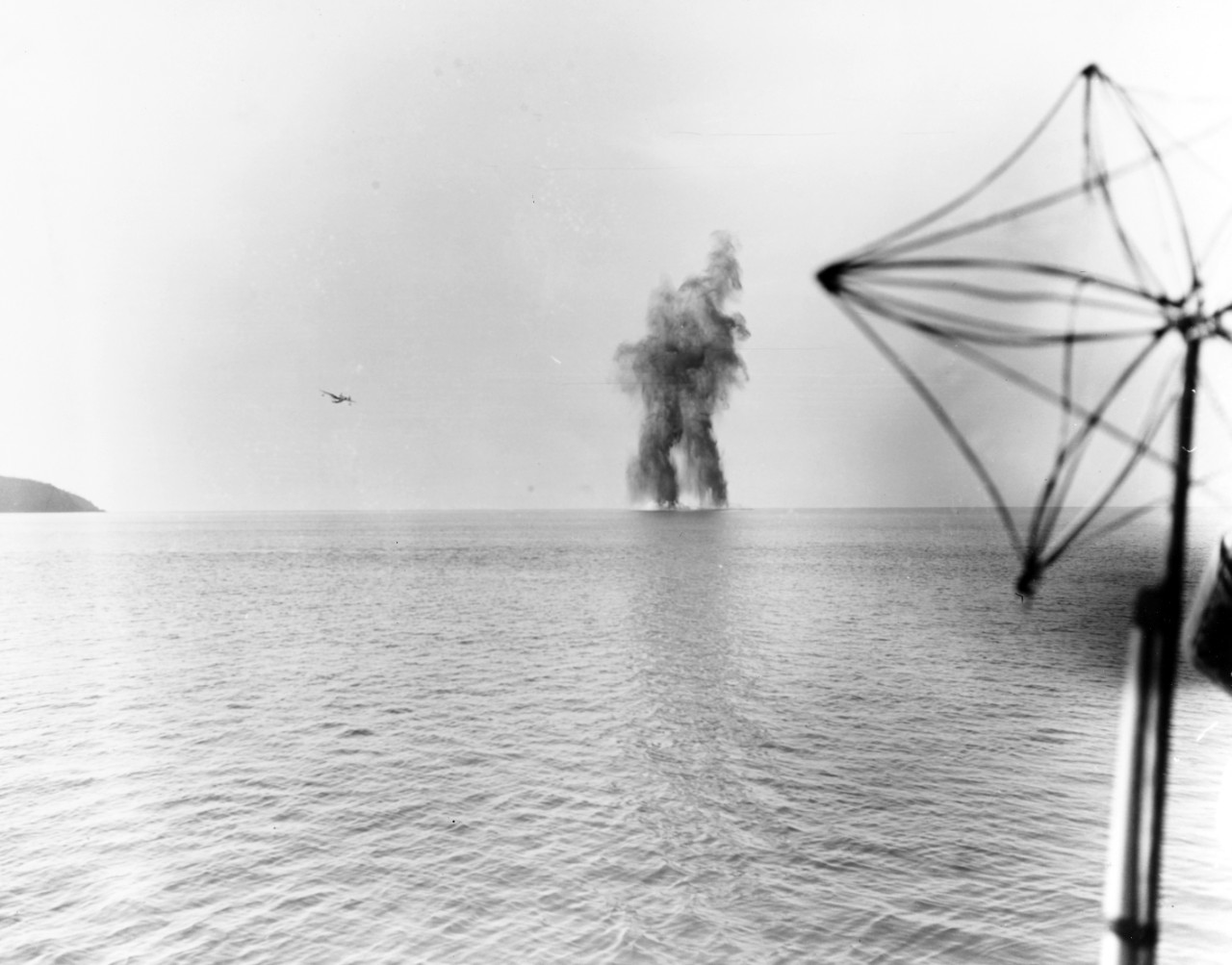

Martin PBM Mariner Patrol Bomber Explodes Russian-type mines with machine gun fire, in the channel near Chinnampo, North Korea. The original photo is dated 20 August 1953, after the Korean War armistice. It may have been taken in October-November 1950, when patrol aircraft were employed to search for and destroy mines to open Chinnampo for the use of advancing United Nations' forces. Official U.S. Navy Photograph, now in the collections of the National Archives. (80-G-423162)

11 October 1950

At dawn on 11 October, minesweeping commenced on the Russian Route. A VP-47 PBM Mariner circled overhead, scouting, plotting, and reporting minefields. UDT personnel from Diachenko and just-arrived fast transport Wantuck (UDT ONE and UDT THREE) scouted the shorelines of Yo Do, Ung Do, and other islands for signs of command-detonated minefields (none were found). Messages were sent to friendly forces ashore (already in Wonsan) to look for any charts that the North Koreans might have left behind with the positions of the minefields. This time Pirate, Pledge, and Incredible conducted the sweep with a helicopter leading the way, while Kite and Redhead trailed behind marking the channel. By sunset, the force had advanced to within four miles of the island and 16 mines had been cut and destroyed; one mine got stuck in Pirate’s sweep gear and had to be towed out to sea.

As the minesweeping off Wonsan was going on, carrier aircraft from TF 77 were hammering targets from Wonsan and to the north up the east coast of North Korea, sinking coastal vessels off Wonsan, Hungnam, and Songjin, while also targeting railroads, trucks, warehouses, and supply dumps around Songjin.

12 October 1950, A Really Bad Day

On 12 October, VADM Struble on Missouri arrived near Wonsan, rendezvoused with RADM Hartman’s cruisers, screened by a UN force of British, Australian, and Canadian destroyers, and steamed northward along the east coast of North Korea to pummel warehouses, marshaling yards, and rolling stock at Chongjin. The rest of the day didn’t go so well.

The day began with a new innovation, aerial countermining using bombs. The visual effect was spectacular, the results not so much. Carriers Philippine Sea and Leyte launched 47 aircraft. Eight F4U Corsairs were held in airborne reserve, while 31 AD Skyraiders, with three 1,000-pound bombs each, and 16 Corsairs, with one 1,000-pound bomb each, bombed at intervals along two parallel five-mile long strips of water. About 109 bombs were actually dropped. The idea was that the bombs would detonate any mines in the area. The problem was that it was very difficult to bomb at the required evenly spaced intervals. As a result, there were large gaps in coverage. The event was deemed a partial success but does not appear to have been repeated, and it was quickly overtaken by the events of the day.

Minesweeping operations commenced late morning on 12 October, entering unswept waters at 1112. Once again a helicopter led the way, with a PBM Mariner flying boat providing support. The three steel minesweepers formed a standard echelon minesweeping formation with Pirate in the lead, followed behind and to starboard by Pledge and then Incredible. The “danning” vessel, wooden minesweeper Redhead, trailed Pirate at the outer port edge of Pirate’s sweep gear, dropping buoys to mark the cleared channel. Kite did the same on Incredible’s starboard side. Destroyer-minesweeper Endicott followed close behind the minesweeper group to provide quick-reaction fire support in the event shore batteries were encountered (so far there had been none).

Leading the formation was Lieutenant Commander Bruce Hyatt, Commander of Mine Division 32, embarked on Pirate, which was commanded by Lieutenant Cornelius McMullen. The ships were at Condition Able with the degaussing on the steel minesweepers energized, and in accordance with doctrine, all non-essential personnel were topside and spread out to minimize casualties in the event of a mine strike. The 3-inch guns on the steel minesweepers were manned and ready, although the gun crews were drawn back to less exposed locations as the orders were to fire only if fired upon.

Shortly after noon, everything went to hell. The helicopter reported three mine lines ahead, followed by a report of a “cabbage patch” of mines directly ahead. Pirate’s sonar began picking up probable mine shapes. In quick succession, Pirate’s cutters brought up five mines to port and one to starboard. Pledge’s gear brought up three mines to port and Incredible four more. Thirteen contact mines were now bobbing on the surface. A Pirate lookout sighted a mine directly ahead. Pirate tried to maneuver clear but it was too late.

At 1209, a massive explosion blew a hole the “size of a two-car garage” amidships at frame 62. The blast knocked the commanding officer, Lieutenant McMullen, unconscious for about 30 seconds and dazed everyone else on the bridge. When he came to, Pirate was listing 20-degrees and righting herself, but that proved only temporary. Within a minute the ship was listing 15-degrees and continuing to go over, while the stern was already underwater. LT McMullen gave the order to abandon ship. Those who survived the blast were able to get off in an orderly fashion and the CO and XO were the last off just as the mast went into the water. Pirate went down in four minutes.

The skipper of Pledge, Lieutenant Richard O. Young, ordered the sweep gear cut and the ship to a halt to lower a boat to rescue survivors. Previously undetected North Korean shore batteries on Sin Do then opened “withering” fire on the sinking and stopped minesweepers, and on the survivors in the water. Reports also described machine gun fire and shrapnel hitting amongst the survivors.

Endicott promptly opened fire on the North Korean guns, as did Pledge and the other minesweepers. Diachenko and the other wooden minesweepers of MINDIV 31 (LCDR Shouldice) also rushed forward to engage and look for survivors. The PBM overhead spotted the positions and called for TF 77 airstrikes. As the gun-battle raged, Pledge maneuvered to avoid the incoming fire (and the minefield that surrounded her). In doing so, Pledge struck a struck a mine at 1220, with the same result as Pirate, except it took 45 minutes for her to sink despite heroic efforts to save her. During the gun battle, both engines in Incredible conked out and she went dead-in-the-water and would have to be towed from the scene. The cumulative fire from Endicott and the minesweepers finally silenced the North Korean guns, and vigorous air strikes by Leyte aircraft with guns, 500-pound bombs, and napalm shut them down for good.

The rest of the afternoon was focused on searching for survivors from Pirate and Pledge. Pledge’s boat (launched before Pledge hit the mine) rescued many, as did a boat from Incredible. UDT Frogmen from Diachenko were particularly valorous in rescuing survivors (three would be awarded Bronze Stars). Aided by the searching helicopter, the boats towed men in rafts and nets to Endicott. Destroyer-minesweeper Doyle also joined in the search.

Of Pirate’s 77-man crew, six were missing and never found and 43 were wounded. LCDR Hyatt and his Quartermaster (the Mine Division “staff”) embarked on Pirate also survived. Of Pledge’s 72-man crew (two others were not aboard), six were missing and one died after being rescued. Two Japanese “visitors” on Pledge also survived. When combined with the mine strikes on Magpie, Brush, and Mansfield, in the space of three weeks North Korean mines had sunk three U.S. minesweepers and severely damaged two destroyers, with the loss of a total 47 Sailors. (There are differing accounts of the number of Sailors lost on Pledge, with one source listing nine names as killed. The total number of crewmen wounded also differs between sources).

Upon word of the mine strikes, VADM Struble (CJTF 7) and RADM Allen “Hoke” Smith (CTF 95) jumped aboard destroyer Rowan (DD-782) and steamed to the scene, not that there was much they could do at that point. RADM Smith subsequently sent his colorful message to Washington, “We have lost control of the seas to a nation without a Navy, using pre-World War I weapons, laid by vessels that were utilized at the time of the birth of Christ.” This was arguably an exaggeration, given four aircraft carriers, two escort carriers, a battleship, and a host of cruisers and destroyers off the coast, but it did get attention and resulted in a flurry of activity back in the states to improve U.S. mine-countermeasure capability. Nevertheless, RADM Smith had a point that the array of ships and 50,000 Marines and Army Soldiers weren’t going into Wonsan (even in friendly hands) until the handful of minesweepers completed their task. And as the saying goes, “Where minesweepers go, the fleet follows.” (On 16 October, the CNO moved the reactivation of nine AMSs to the highest priority and added four AMs to the list. A rapid research and development program was launched, a Mine Force Type Command was stood up (again), and by 11 November, Minesweeping Force Western Pacific was stood up under the command of RADM Higgins).

Engineman Third Class Harry L. Link and Lieutenant (junior grade) Aubrey McIlvaine were each awarded the Silver Star for their actions aboard Pledge in saving crewmen and attempting to save the ship. The Commanding Officer of Mine Division 32 and of each of the minesweepers was awarded the Silver Star; LCDR Hyatt (MINDIV 32), LT Cornelius McMullen (Pirate), LT Richard O. Young (Pledge), LT Edward Flynn (Incredible), LTJG T. R. Howard (Redhead), LTJG Nicholas Grkovic (Kite), LTJG Robert Fuller (Partridge), LTJG James McMahon (Chatterer), LT Philip Levin (Osprey) and LTJG Stanley Gary (Mockingbird). The dates of action include following minesweeping operations in the next days.

The Commander of Mine Division 31 (the “wooden” minesweepers), Lieutenant Commander D’arcy V. Shouldice, embarked in Mockingbird was awarded the Navy Cross for service as set forth in the following citation:

“The President of the United States takes pleasure in presenting the Navy Cross to Lieutenant Commander D’arcy V. Shouldice, United States Navy for extraordinary heroism in connection with military operations against an armed enemy of the United Nations while serving as Commander of Mine Division 31 and in Tactical Command of that Division during mine sweeping operations off Wonsan Harbor, on the coast of Korea, on 12 October 1950. When two heavy minesweepers of another Division were mined within a few minutes of each other and were still under severe enemy gunfire from hostile shore batteries, Lieutenant Commander Shouldice led his Division into supporting positions exposed to enemy fire in order to rescue survivors and to take in tow a third heavy minesweeper. Maneuvering his command skillfully throughout this operation in un-swept and densely mined waters, he returned effective gunfire against enemy shore batteries until his Division and tow had reached safe waters without further loss or serious damage. In the following days, Lieutenant Commander Shouldice continued to lead his division in the vital task of sweeping heavily mined areas until an anchorage and channel had been cleared to the landing beaches, thereby contributing essentially to the success of Naval Operations in the Wonsan area. His inspiring leadership and gallant devotion to duty were in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.”

All of the minesweepers in action at Wonsan on 12 October, plus Merganser, and the staffs of Mine Division 31 and 32 were awarded a Presidential Unit Citation for the period 10-24 October 1950. Pirate’s citation follows:

“The President of the United States takes pleasure in presenting the PRESIDENTIAL UNIT CITATION to the USS PIRATE (AM-275) (including Commander Mine Division THIRTY TWO and staff serving in PIRATE) for service as set forth in the following CITATION: “For outstanding performance in action during operations against enemy aggressor forces in Korea on 11 and 12 October 1950. Operating as part of Task Element 95.62, the USS PIRATE assisted in the extremely hazardous and difficult task of sweeping and buoying a channel 2,000 yards wide and 14 miles in length, to the outer limits of Wonsan Harbor, during which time heavy concentrations of enemy contact mines were swept in the face of the ever present threat of mine explosions and attack from hidden hostile gun batteries on the beaches and surrounding islands. On 12 October, after leading the assault formation in a dual role as Flagship for Commander Mine Division THIRTY-TWO and minesweeper in the clearance of a channel through two heavy contact-type minefields, the PIRATE encountered a third field of extreme density, struck a mine and sank in approximately four minutes with casualties numbered at six killed and forty-three wounded. During rescue operations, her survivors were repeatedly fired upon by enemy shore batteries and machine guns. The fortitude, superb teamwork and unrelenting determination of each individual serving on board PIRATE were contributing factors in the success of vital minesweeping operations and were in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.” For the President, C. S. Thomas, Secretary of the Navy.

13 October 1950

Despite the losses on 12 October, mine clearance operations resumed the next day, although it became increasingly apparent that sweeping would not be complete by the 20 October D-Day, although the occupation of Wonson by ROK forces made that date less critical. Four small minesweepers of LCDR Shouldice’s MINDIV 31 now shouldered the brunt of the sweeping, with additional ROK and JMS minesweepers pressed into the action. In addition to the conventional minesweepers, UDT in small boats (as many as could be rounded up) also conducted search operations.

Also on 13 October, divers went down to the wrecks of Pirate and Pledge for the retrieval or destruction of any sensitive gear or materials, such was crypto material. The wrecks were then subsequently destroyed. Two years later the skipper of Pirate, LT McMullen, received an anonymous package that included a note and the 48-star flag that had flown on Pirate and that had been brought up from the wreck, according to the note. In 1985, Captain (Ret). McMullen donated that flag to the Naval History and Heritage Command (then Naval Historical Center) and it remains on display in the Korean War section of the Cold War Gallery of the National Museum of the United States Navy.

In other events on Friday the 13th, RADM Hartman’s cruiser group, joined by heavy cruiser Toledo coming from Sasebo, bombarded five separate targets along the east coast of North Korea. At the same time, the U.S. Air Force attacked numerous targets elsewhere in North Korea, the UN surface force commanded by RADM Andrewes, RN, bombarded targets on the west coast of North Korea near Haeju, and the British carrier Theseus, operating in the Yellow Sea, bombed targets around the port of Chinnampo. These targets had all been announced in advance as part of a UN psychological campaign to convince the North Koreans to surrender by demonstrating that the UN forces could strike any targets at will. In terms of convincing the North Koreans to surrender, the impact of the operation was zero.

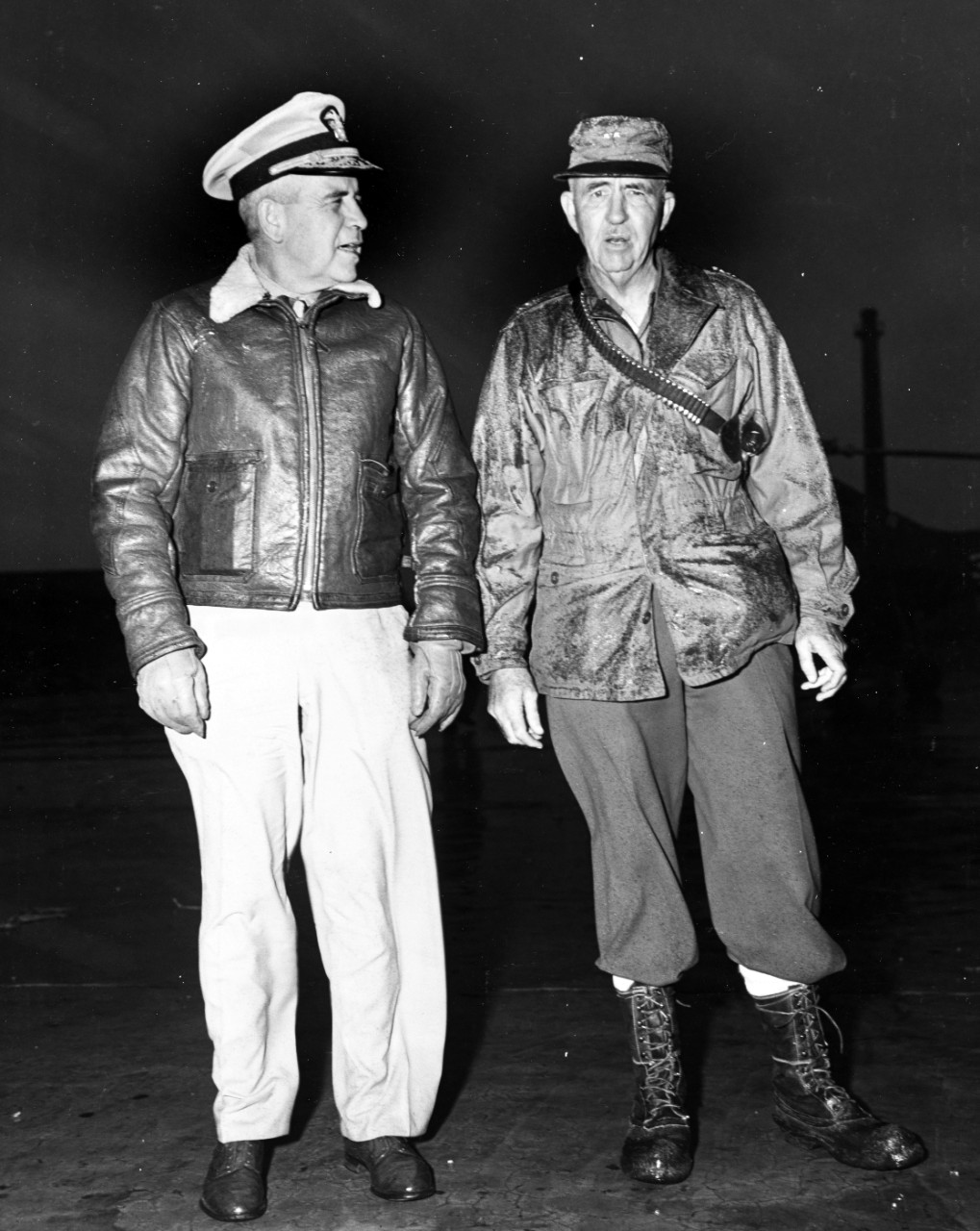

Lastly, U.S. Marine Major General Field Harris flew into Wonsan to survey the airfield, and promptly ordered two USMC squadrons into the airfield to commence flight operations the next day. He also suggested that since the South Koreans were already in control of Wonsan that the amphibious assault be canceled. However, the momentum of the operation, coupled with the snarled logistics situation in South Korea, precluded a major change of plans at this point. Although the operation could be changed from an amphibious assault to an administrative landing, the troops of the 1st Marine Division and 7th Infantry Division were still going to come in by sea.

Vice Admiral C. Turner Joy, USN, Commander U.S. Naval Forces Far East (at left), is greeted at Wonsan airfield by Major General Field Harris, USMC, Commanding General of the First Marine Air Wing, 19 October 1950. Elements of the Wing had arrived at Wonsan by air on 13-17 October. Flight operations were sustained by aerial resupply until the landing beaches were opened on 26 October. Note MGen. Harris' shoulder holster and ammunition for a .38 caliber revolver. Official U.S. Navy Photograph, now in the collections of the National Archives.

14 October 1950

By the end of 14 October, a channel had been cleared of contact mines, and sweeps commenced to locate any magnetic bottom influence mines. To this point, there had been no evidence of any. Also on 14 October, Marine Fighter Squadron VMF-312 began flight operations from the airfield at Wonsan, but would quickly need sustainment from the sea.

15-17 October 1950

Between 14-16 October, Lieutenant Commander Don C. DeForest had gone ashore to gather intelligence on possible mine locations. As he was transiting along the shore in an LCVP, the landing craft struck a moored contact mine that had popped to the surface and miraculously didn’t break any of the five horns on the mine. Forest was close enough to read the serial number on the mine ─11825. DeForest also braved a transit along a sniper-infested road and risked capture to reach a fishing village. There, using the power of a chocolate candy bar to win over a little girl, he then coaxed first the women and then the men, fearful of North Korean retribution, to come out of hiding. When he showed a schematic of a magnetic influence mine, a fisherman led him to a haystack that hid a coil from a magnetic mine, confirming the presence of such mines, and also provided intelligence necessary for devising effective sweep methods. Fishermen also became increasingly cooperative when offered cigarettes and rations, and soon a number of local fishermen were out in their boats searching and reporting mines. LCDR DeForest would be awarded the Silver Star for his exploits. (Accounts differ as to the order and dates of these events, and his award citation covers a range of dates).

By 15 October, CAPT Spofford was convinced that a channel to Wonsan had been cleared of moored contact mines. Subsequently, Diachenko made a safe passage to the outskirts of the harbor. On 16 October, a North Korean prisoner of war reported that magnetic mines had been laid in Wonsan. The next day, contradictory reporting was received, but LCDR DeForest’s recovery of a coil from a magnetic mine strongly suggested such mines had been laid. This was about to be confirmed beyond any doubt.

On 17 October 1950, Japanese contract minesweeper MS-14 struck a contact mine and sank off the southern shore of Yo Do in the approaches to Wonsan, with one crewman killed and 18 wounded. General MacArthur imposed a news blackout of the sinking to minimize any political blowback in Japan to Japanese ships and personnel being used in a combat zone.

Also, on 17 October, ROK LST BM SF-673 struck a mine in the Wonsan outer harbor after cutting a corner; fortunately the ship suffered only minor damage and no deaths, and continued into port.

On the same day, the massive Wonsan attack force got underway from Inchon, having re-embarked the 1st Marine Division and the heavy vehicles of the 7th Infantry Division. The troops of the 7th Infantry Division had gone south by truck to embark ships at Pusan.

Also on 17 October, heavy cruiser Helena and light cruiser Worcester shelled the port of Songjin north of Wonsan, but enemy activity along the entire east coast of North Korea had effectively ceased so the ships had little to shoot at, and even the aircraft of TF-77 were having a hard time finding useful targets.

Republic of Korea minesweeper YMS-516 sinking in Wonsan harbor, 18 October 1950, after she detonated a magnetic mine during sweeping operations west of Kalma Pando. USS Redhead (AMS-34) is just to the right of the sinking ship, rescuing survivors, as is another minesweeper to the left. Photographed from USS Merganser (AMS-26). ROK YMS-516 was originally the U.S. Navy's YMS-148, which had served in the British navy in 1943-46. Official U.S. Navy Photograph, now in the collections of the National Archives. (80-G-443316)

18 October 1950, Another Bad Day at Wonsan

On 18 October 1950, Shouldice’s minesweepers were conducting what were thought to be final operations off Wonsan when the third ship in the formation (Redhead) triggered a magnetic bottom influence with the kite and float, which resulted in a sympathetic detonation of another mine about 150 yards away. The skipper of Redhead, Lieutenant (junior grade) T. R. Howard, described it as “suddenly the whole ocean started to erupt.” Although, fortunately, no ship was seriously damaged (as neither mine detonation was a direct hit), the minesweepers cut their gear and stopped all machinery except for one engine and slowly moved away. However, inadequate communications capability prevented the U.S. minesweepers from sending a timely warning to a South Korean formation heading for the same spot.

Commanded by Commander Sihak Hyun, ROKN, embarked on Jirisan (PC-704), the original Korean formation was supposed to be led by ROKN minesweeper Gongju (YMS-516), followed by PC-704, YMS-510, and six small power boats bringing up the rear. However, the commanding officer of YMS-516 never acknowledged repeated orders to take the lead. Instead, PC-704 took the lead, followed by a power boat with YMS-516 in third position. As the ROKN force moved forward at one-third speed on one engine, the two explosions were observed detonating just behind the American minesweepers. Still cautiously moving forward, two minutes later a magnetic bottom mine blasted YMS-516, breaking her in two and quickly sending her to the bottom with four crewmen killed and 13 missing. Redhead assisted in rescuing survivors from YMS-516. (PC-704 would hit a mine near Yo Do on 26 December 1951, and was lost with all hands).

18-25 October 1950, Operation Yo-Yo

With a magnetic mine threat now confirmed, VADM Struble had to recommend a postponement of the 20 October D-Day. Although small craft began bringing critical supplies ashore on the 19th, a channel for larger ships would take another week to clear, requiring that the 250-ship Attack Force (and over 50,000 embarked troops), which arrived on 20 October, to continue steaming about smartly off Wonsan in what became known as “Operation Yo-Yo.”

Rear Admiral Doyle, in amphibious command ship Mount Mckinley, arrived off Wonsan on the afternoon of 19 October and anchored in the swept channel. The rest of the Transport and Tractor groups arrived shortly after, but were obliged to remain at sea as magnetic minesweeping operations continued until 25 October. This caused a number of problems as food aboard the ships began to run out, but extended close-quarters also encourage the spread of various contagious ailments. The worst was an outbreak of dysentery aboard the MSTS transport Marine Phoenix which sickened 700 of 2,000 troops aboard (84 had to be hospitalized) and a similar percentage of the crew.

At 1500 on 25 October, ships of the Attack Force began moving through the swept channel. Five LSTs were beached, and offloading began at dawn on 26 October. The 1st Marines landed on Yellow Beach and the 7th Marines on Blue beach, in accordance with the original plan, except no one was shooting at them. Actually, the Marines were welcomed by banners from the ROK troops who’d been in the city since 10 October, as well as another banner “This beach is all yours courtesy of Mine Squadron THREE.” Perhaps worse, the X Corps Commander, Army Major General Almond, was already there to greet them along with comedian Bob Hope and a USO troop. Having endured days of seasickness during Operation Yo-Yo, most of the Marines were apparently not amused.

The 5th Marine Regimental Combat Team landed on 27 October. By the evening of the 26th, over half the 25,000 men in the 1st Marine Division, 2,000 vehicles, and 2,000 tons of cargo were ashore.

Despite the delay of 6 days caused by the mines, a major Marine force was ashore and ready for offensive operations, having suffered no casualties (except to dysentery), although the front was 50 miles to the north and advancing rapidly. ROK troops had taken the significant port of Hungnam (and city of Hamhung) on 17 October.

LCMs unloading on the Kalmo Pando beaches, at Wonsan, North Korea, with LVTs standing by to assist, 26 October 1950. The stranded LCVP in the right background is from USS Bexar (APA-237). Several LSTs are beached beyond that. Official U.S. Navy Photograph, now in the collections of the National Archives. (80-G-421315)

Post-Wonsan Operations on East Coast of North Korea

Before moving out from Wonsan, one Marine battalion was ordered to Kojo, on the coast 30 miles south of Wonsan, to deal with some holdout North Korean forces in the nearby hills. A Marine airstrike had found about 800 North Korean troops in the area. On 24 October, destroyer-minelayers Endicott and Doyle swept a channel into Kojo, although the Marine battalion wound up going south by train. On the night of 27 October, the North Koreans launched a surprise attack into Kojo that achieved some initial success, prompting calls for air and naval gunfire support and helicopter evacuation of the wounded. The escort carriers Sicily and Badoeng Strait, with embarked Marine F4U Corsair squadrons, had arrived off Wonsan on 18 October and responded to the threat. Destroyers Hank (DD-702) and English (DD-696) took the North Koreans under fire while LST-883 departed Wonsan with a load of tanks. A second Marine battalion arrived by rail, and the North Korean attack was ultimately defeated.

The original mission of X Corps was to attack westward from Inchon to link with the Eighth Army near Pyongyang and cut off retreating North Korean forces. This was actually OBE (overtaken by events) even before the originally scheduled D-Day at Wonsan on 20 October. On 25 October, X Corps received revised orders to attack north toward the 40th Parallel limiting line. VADM Struble, MG Almond, and RADM Doyle met to discuss the change of mission. To speed the northward movement, they agreed to land at least two regiments of the 7th Infantry Division at Iwon, 90 miles north of Wonsan, which also was already in ROK hands. Destroyer-minesweepers Endicott and Doyle, along with one AMS, were dispatched to Iwon and between 25-26 October cleared a 19-mile channel without discovering any mines.

RADM Thackrey, Commander Amphibious Group Three, embarked in command ship Eldorado (AGC-11) took charge of landing the 7th Infantry Division at Iwon. This proved to be a challenge because the ships carrying the 7th ID were configured for an administrative landing (i.e., they lacked landing craft) and it turned out Iwon lacked anywhere near enough lighterage. As a result, everything had to be craned from the ships onto LSTs (with a fair amount of equipment damage due to swell in the unprotected anchorage). Nevertheless, by 30 October, one regiment was ashore and by 8 November, the entire division of 29,000 men was ashore.

On 1 November, Communist guerillas threatened Kosong, on the coast 60 miles south of Wonsan. ROK troops were loaded onto two LSTs, which left Wonsan. Endicott and Doyle once again swept a channel, finding no mines, and the ROK troops were successfully landed (unopposed) and dealt with the situation.

Marines boarding USS Bayfield (APA-33) at Hungnam, for transportation out of North Korea. Note details of the Marines' packs. Man at left is carrying a Russian Mosin-Nagant carbine in addition to his M1. This photograph was released by Commander, Naval Forces Far East, under date of 20 December 1950. Official U.S. Navy Photograph, from the collections of the Naval History and Heritage Command. (NH 97060)

In the meantime, Major General Almond selected the city of Hamhung to be X Corps headquarters and the minesweepers set to work clearing the port of Hungnam, which served Hamhung. Hungnam was slightly bigger than Wonsan and located about 50 miles farther north. Intelligence reports indicated at least 100 mines had been laid at Hungnam. A cooperative captain of one of the North Korean minelaying vessels (who apparently had avoided being executed by the retreating North Koreans) provided detailed information on the mines; an inner line was laid by two ships carrying 18 mines each, and an outer line was laid by three ships─two with 18 mines and one with 20 mines─for a total of 92. The cooperative captain stated that a Russian navigator had been aboard during the minelaying operation. The captain was unsure if any magnetic mines had been laid.

On 7 November, destroyer-minesweeper Doyle, seven AMSs, and supporting units commenced clearance operations at Hungnam. Aided by the intelligence from the cooperative captain, helicopters and small boat reconnaissance was so successful that a route was found that avoided the mines. The only contact mines swept were well clear of the designated channel. Sweeps for magnetic mines turned up none. Upon completion of the Hungnam operation, the minesweepers moved further north to clear Songjin (35 miles further north than Iwon). Between 16 and 19 November, seven AMSs swept the approaches and harbor of Songjin and found no mines. The next planned minesweeping operation at Chongjin (north of Songjin) would be aborted due to the massive surprise Communist Chinese offensive (which will be covered in the next H-gram).

Chinnampo, West Coast Landing

As the operation at Wonsan was getting bogged down by mines, a parallel effort was getting underway on the west coast of North Korea at the port of Chinnampo. As the U.S. Eighth Army advanced northwestwards, its logistics situation became increasingly acute as supplies coming in to the inadequate port at Inchon then had to go through the bottleneck at Seoul. The commander of the Eighth Army, General Walton Walker, requested that a port be opened up on the west coast of North Korea. VADM Turner Joy, COMNAVFE, was sympathetic to the Eighth Army’s situation but there were initially insufficient minesweepers to support any such operation, but one would be mounted as soon as possible.

In mid-October, Japanese contract minesweepers (JMS) cleared a route into the small North Korean port of Haeju, but this wasn’t far enough north to be of much help to the Eighth Army.

The major port on the west coast of North Korea was Chinnampo, located ten miles up a tidal river (the North Korean capital of Pyongyang was further up the river). Chinnampo was very similar to Inchon in terms of the great daily tidal variation and strong tidal currents. The approach to Chinnampo was 30 miles long, and was lined with islands and mud banks. In terms of port capacity, it was less than Inchon, but had the advantage of being the only real alternative on the west coast.

As it became apparent that the landing at Wonsan would not be opposed (except by mines), RADM Smith (CTF 95) was released from his duties to return to Sasebo and scrounge another minesweeper force to conduct the Chinnampo operation as soon as possible. In the meantime, the Eighthy Army had captured the North Korean capital of Pyongyang in a battle around 17-19 October, with logistical challenges becoming even more acute, bogging down the offensive north of Pyonhyang. Eighth Army personnel occupied the port of Chinnampo about the same time.

Fortuitously, on 22 October, the remaining two destroyer-minesweepers in the Pacific Fleet, Thompson (DD-627) and Carmick (DD-493) arrived at Sasebo. The next day, three wooden minesweepers of Mine Division 51 arrived at Sasebo from Pearl Harbor (Pelican (AMS-32), Gull (AMS-16), and Swallow (AMS-36)). With these minesweepers as a nucleus, supported by destroyer Forrest Royal (DD-872), Task Element 95.69 was formed under the command of Commander Stephen M. Archer. Archer had previously commanded the Underwater Reconnaissance Element at Wonsan (for which he would be awarded a Silver Star). Archer was aided by the efforts of Commander Donald Clay, who formed an intelligence collection team that scouted the approaches to Chinnampo in advance of the minesweeping effort and provided much useful information. Archer was also aided by the rapid transmission of lessons learned from the Wonsan operation, the biggest of which was search first, then sweep. (Searching and sweeping at the same time led to the loss of Pirate and Pledge). In addition, the object became to find a way around the minefields, if possible, rather than try to sweep the way through them.

As CTE 95.69 set off for Chinnampo, the PBM Mariners shifted reconnaissance operations from the east coast back to the Yellow Sea, now with much greater on-station time thanks to the seaplane tender Gardiners Bay at Chinhae, South Korea. British Sunderland flying boats also participated in these searches. The initial searches were hampered by large numbers of big jellyfish (four feet across) that drifted just below the surface, resulting in numerous false alarms. Nevertheless, in the first three days of searching, 34 mines were located and 16 were destroyed by strafing from the PBMs. An attempt to innovate using depth charges to destroy magnetic mines had mixed results. The helicopter from light cruiser Worcester was also temporarily embarked on carrier HMS Theseus to support the minesweepers.

As the entire Yellow Sea is a mineable depth (like the Arabian Gulf) sweeping began at an arbitrary point 30 miles from the entrance to the channel to Chinnampo (almost 70 miles to the docks in the port). On 29 October, destroyer minesweepers Thompson and Carmick commenced sweep operations in the outer approaches. (This was actually somewhat rare; although destroyer-minesweepers were obviously equipped to clear mines, they were generally used in WWII to provide fire support (and antiaircraft support) for regular minesweepers, and for standard destroyer-type duties). On 31 October, CDR Archer arrived on Forrest Royal along with the three AMS minesweepers, two ROKN YMS minesweepers (later joined by two more), and fast-transport Horace A. Bass with underwater demolition team ONE embarked (UDT-1), and salvage ship Bolster (ARS-38). A Scajap LST (Q-007) relieved Theseus as a platform for the minesweeping scout helicopter.

The significant tidal variation (twelve feet) at Chinnampo proved to be an advantage relative to Wonsan, as low tide tended to expose the moored contact mines. So searching was done at low tide and sweeping at high tide. By 2 November, CDR Clay and LTJG Hong, ROKN, had discovered (thanks to a cooperative North Korean river pilot) and charted a pattern of 217 moored mines and 25 magnetic mines laid in five lines across main channel north of Sok-to Island and one line across an alternate more shallow (15 feet at high tide) and longer route to the south of Sok-to. As a result of this information, CDR Archer decided to clear the alternate passage first. On 3 November, a ROKN YMS made a safe passage through the southern route. On 4-5 November, high winds caused a number of moored mines to break free, which were then destroyed as they floated on the surface.

About that time dock landing ship Catamount (LSD-17) arrived loaded with gear to act as a mother ship for 14 LCVP landing craft (four of which were rigged for sweeping moored mines and four for sweeping magnetic mines), which could search for mines in shallow water where other ships couldn’t go. Catamount was the first LSD to engage in minesweeping operations. Four 40-foot launches from carrier Boxer were also brought in and rigged as minesweepers. Although the LCVPs and small boats were useful searching for mines, the effort to use them to sweep was mostly a failure as the fast currents caused the boats to burn out their engines when trailing sweep gear. Nevertheless, on 6 November, an ROKN YMS escorted tugs and barges through the southern channel, and the first small freighter went through the next day.

The minesweeping operation then shifted to the main (and more heavily mined) deep water channel, assisted by the arrival of a 13 Japanese contract mineweepers (operating well north of the 38th parallel, a politically sensitive matter). The JMS minesweepers were also tended by a mother ship and assisted by a “trial” ship. By 17 November, 14 ships reached Chinampo and 40,000 tons of supplies were offloaded, highlighted by the arrival of hospital ship Repose (AH-16).

Benefiting from lessons learned the hard way at Wonsan, the operation at Chinnampo was conducted without loss or damage to any ships, or loss of any crewmen. Commander Archer was awarded a Legion of Merit with Combat V as commander of TE 95.69. Most mines encountered were marked and bypassed. Of 80 moored mines that were actually destroyed, 36 were credited to PBM strafing, 27 to UDT demolition from small boats, 12 as result of the storms, and only five were actually cut and destroyed by minesweepers. Four magnetic mines were also found and destroyed. Planes from Theseus also destroyed a barge that was in the act of laying mines, and the sunken barge was later found with 15 mines still aboard. Although the mines at Chinnampo inflicted no losses, they were successful in the sense of causing several weeks’ delay in opening a key port, at significant cost to the logistics effort in support of Eighth Army’s offensive.

East Coast Operations – November 1950

On 10 November 1950, a PBM Mariner flying boat located and destroyed nine mines northeast of Wonsan, outside the bay area. The next day, recently-arrived destroyer Buck (DD-761) was seriously damaged in a collision with destroyer John W. Thomason (DD-760), and had to return to the U.S. west coast for repair.

By 20 November, U.S. sealift had brought another Army division (3rd Infantry Division) into Wonsan from Japan. Also on 20 November, the Secretary of the Navy, Francis P. “Rowboat” Matthews, arrived in Korea and went aboard the command ship Mount Mckinley. It was the first time in his year-and-a-half tenure that he had gone aboard any ship of the U.S. Navy!!!

Secretary of the Navy Francis P. Matthews (right) talks with Vice Admiral Arthur D. Struble, Commander Seventh Fleet, (left) and Vice Admiral C. Turner Joy, Commander Naval Forces Far East, (center), upon his arrival at Wonsan airfield, North Korea, for Korean war conferences. The original photograph is dated 23 November 1950, but may have been taken on 20 November. See James A. Field, Jr., History of United States Naval Operations Korea (1962), page 250. Official U.S. Navy Photograph, now in the collections of the National Archives. (80-G-424550)

The mines at Wonsan weren’t quite done yet. On 16 November 1950, Army tug LT-236, towing a crane barge, triggered a mine and went to the bottom with 30 of 40 aboard (the largest loss of life in a mine strike during the war). Among those killed were 22 of 27 Japanese contract laborers aboard, a fact that was kept under wraps due to political concerns in Japan.

RADM Allen Smith’s official post-Wonsan report stated, “The Navy able to sink an enemy fleet, to defeat aircraft and submarines, to do precision bombing, rocket attack and gunnery, to support troops ashore and blockade, met a massive 3,000 mine field laid off Wonsan by the Soviet naval experts….The strongest Navy in the world had to remain in the Sea of Japan while a few minesweepers struggled to clear Wonsan.”

The next H-gram will cover Naval Operations during the Chinese Offensive and Evacuation of U.S. forces from Hungnam following the U.S. Marine Corps’ epic fighting retreat from Chosin Reservoir in December 1950.

Sources include; Assault from the Sea: The Amphibious Landing at Inchon, by NHHC Historian Curtis Utz: Naval Historical Center, 1994. A Study of the United States Navy’s Minesweeping Efforts in the Korean War, by Stephen D. Blanton: Texas Tech Master of Arts Thesis, August 1993. Damn the Torpedoes: A short History of U.S. Naval Mine Countermeasures, 1777-1991, by Tamara Moser Melia: Naval Historical Center, 1991. "Silently. Quickly. By Sea, in Darkness: How U.S. Submarines Helped Special Troops Destroy Enemy Supply Lines in the Korean War," by Nathaniel Patch: Prologue Magazine, Winter 2016, Vol 48, No.4. Attack from the Sky: Naval Air Operations in the Korean War, by Richard C. Knott: Naval Historical Center, 2002. “United States Naval Aviation, 1910-2010, Vol. I, Chronology by Mark L. Evans and Roy A. Grossnick: Naval History and Heritage Command, 2015. “Korean War, U.S. Pacific Fleet Interim Evaluation Report No. 1, 25 June to 15 Nov 1950” at history.navy.mil. “Naval Battles of the Korean War,” by Edward J. Marolda, at history.navy.mil. History of United States Naval Operations: Korea, by James A. Field: U.S. Navy History Division, 1962. USS Pirate, Report of Loss: USS Pirate War Diary, C.E. McMullen, 12 Nov 50.