H-068-1: Captain Albert Rooks and USS Houston’s Last Stand

H-Gram 068, Attachment 1

(Adapted from H-Gram 003 of February 2017)

Samuel J. Cox, Director NHHC

March 2022

According to one witness, when the heavy cruiser USS Houston (CA-30) pulled into Tanjung Priok (the port for Batavia—now Jakarta), Dutch East Indies, on 28 February 1942, having barely survived the hours-long gunnery duel of the disastrous Battle of the Java Sea the day and night before, the ship’s cat deserted. The story is possibly apocryphal, although what is more certain is that the Australian light cruiser HMAS Perth’s black cat (named Red Lead) attempted to desert in the same way in the same port at the same time. Along with the cat went Houston’s luck. The ship had survived over 80 days as the largest Allied warship in the Far East, with no air cover and under multiple bombing attacks and the constant threat from the same kind of aircraft that had made short work of the British battleship HMS Prince of Wales and battlecruiser HMS Repulse on 10 December 1941.

Seriously damaged in one air attack, and having survived the Battle of Java Sea, Houston, in company with Perth, would go into battle that night near the Sunda Strait against overwhelming odds from which neither ship nor most of their crews would survive. Within the next several days, other remaining ships of the U.S. Asiatic Fleet would meet the same fate, in a number of cases alone, against insurmountable odds, with no survivors, but in every case with incredible valor.

Houston (CA-30) was a Northampton-class cruiser, commissioned on 17 June 1930. She was initially classed as a light cruiser (CL-30) due to her limited armor protection, which was necessary to keep her under the 10,000-ton Washington Naval Treaty limit. This led to the Northampton class (and preceding Pensacola class) being derisively known in the U.S. Navy as “tin-clads,” although they were very fast. However, the London Naval Treaty of 1930 defined all cruisers with 8-inch guns as heavy cruisers, and Houston was redesignated as heavy cruiser CA-30.

Houston was 600 feet long, with a standard displacement of 9,200 tons. Her main armament consisted of nine 8-inch guns in three triple turrets, two forward and one aft. Her initial fit of four 5-inch guns was increased to eight before the war (four single mounts per side). At Cavite Navy Yard, just prior to the outbreak of hostilities, Houston was fitted with four quad 1.1-inch antiaircraft guns, which proved to be jam-prone. Her initial fit of six 21-inch torpedo tubes was removed early on to save weight. She also carried four SOC Seagull catapult-launched float/scout planes. The aviation section was amidships, which would prove to be a very bad design later in the war in other cruisers.

After her commissioning, Houston assumed duty in February 1931 as the flagship of the U.S. Asiatic Fleet, operating mostly in Chinese waters due to the crisis following the Japanese occupation of Manchuria. Houston made one good will visit to Japan in May 1933 before being relieved as flagship in November 1933 and returning to the U.S. West Coast as part of the Scouting Force and subsequently participating in Fleet Battle Problems in the Pacific and Caribbean.

In July 1934, President Franklin D. Roosevelt embarked on Houston in Annapolis and transited the Panama Canal to Portland, Oregon, via Hawaii. Roosevelt embarked again in October 1934 for a “vacation” cruise via the Cedros Islands, Magdalena Bay, Mexico, and the Cocos Islands to Charleston, South Carolina, via the Panama Canal. In July 1938, Roosevelt embarked on Houston to observe the San Francisco Naval Review, then remained on board for a 24-day cruise to Pensacola, with ample time for deep-sea fishing. In September 1938, Houston assumed duty as the flagship of the United States Fleet. In January 1939, she embarked Roosevelt again, along with CNO Willam Leahy, to participate in Fleet Battle Problem XX in the Caribbean. Houston next assumed duty as flagship of the Hawaiian Department. On 19 November 1940, the ship returned to the Far East, serving as flagship for the Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Asiatic Fleet, Admiral Thomas C. Hart.

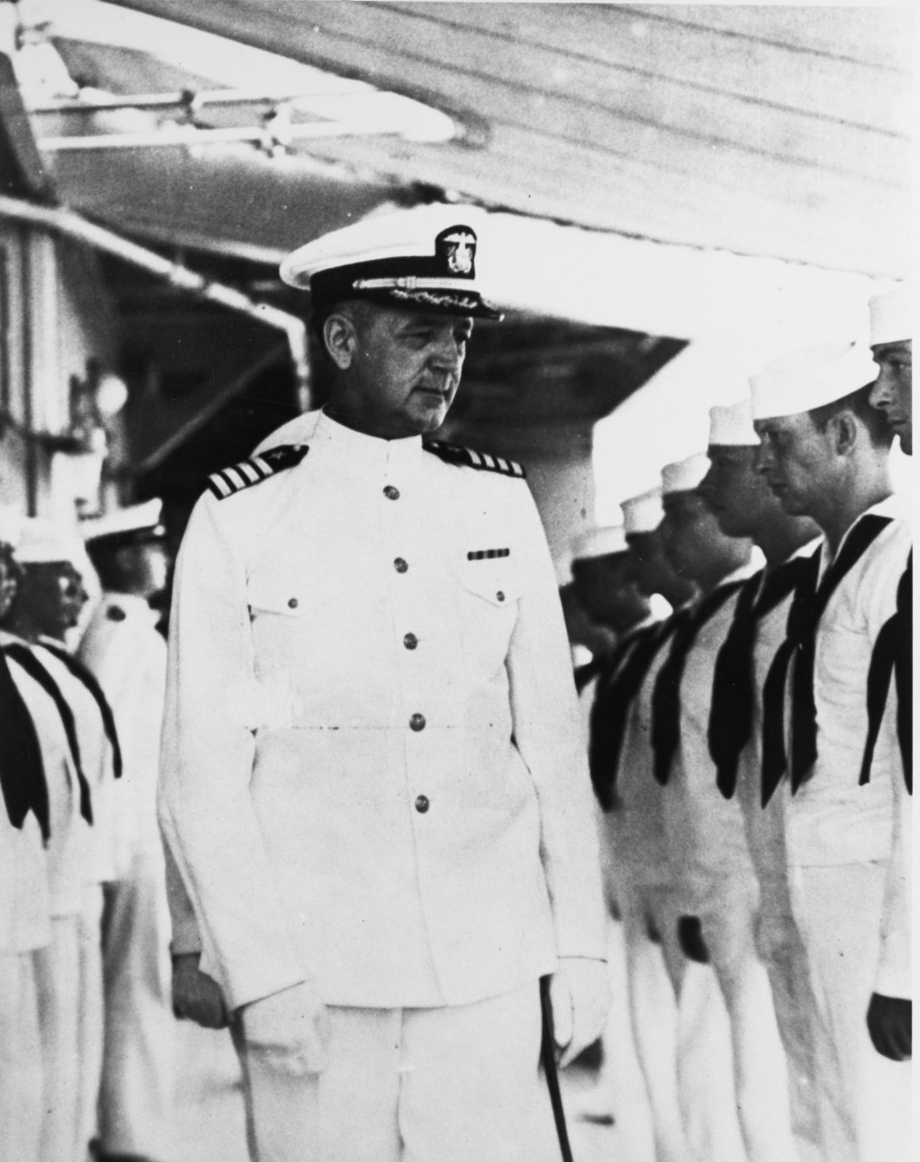

On 30 August 1941, Captain Albert Harold Rooks assumed command of Houston from Captain Jesse B. Oldendorf. Born in Colville, Washington, on 29 December 1891, Albert Rooks entered the U.S. Naval Academy in July 1910. Known as “Rooksey” by his classmates, he was always ready to help anyone out, and was apparently quite a hit with the ladies. His “quiet military manner won for him on our first class cruise a recommendation for the highest cadet rank,” which he did not get. He graduated on 6 June 1914.

Ensign Rooks reported to armored cruiser USS West Virginia (ACR-5) operating off Mexico during the Vera Cruz crisis. In January, Rooks assumed his first command, the 1903-vintage submarine USS A-5, used to defend the approaches to Manila Bay during World War I and which sank at the pier (and was raised) at Cavite in April 1917. This apparently did not hurt his career, because in March 1918, he was assigned to armored cruiser USS Brooklyn (ACR-3), the flagship of the U.S. Asiatic Fleet. As a lieutenant at the end of World War I, he returned to submarine duty as commanding officer of USS F-2 (SS-21) operating out of San Pedro, California. In January 1921, he assumed command of submarine USS H-4 (SS-147), which had been originally built for the Imperial Russian Navy but not delivered after the 1917 Russian Revolution. In January 1922, he was assigned to the 12th Naval District staff in San Francisco and quickly became aide to the district commandant.

In September 1924, Rooks was assigned to the new battleship USS New Mexico (BB-40) and was promoted to lieutenant commander in October 1925. In April 1927, he was assigned as aide to the superintendent of the U.S. Naval Academy. In April 1930, Rooks reported to the new-construction “light” cruiser Northampton, commissioned in May 1930, where he served as gunnery officer on her shakedown cruise to the Mediterranean and transfer to San Pedro, California. In July 1933, Lieutenant Commander Rooks returned to the U.S. Naval Academy for duty. In October 1935, he reported to the destroyer USS Phelps (DD-360), which was under construction, and upon commissioning became her first commanding officer. During this tour, Phelps escorted the heavy cruiser USS Indianapolis (CA-35), with President Franklin Roosevelt embarked, to Buenos Aires, Argentina, for the Inter-American Peace Conference. In July 1938, Commander Rooks reported to the Naval War College in Newport and was retained as faculty after graduation. He was promoted to captain on 1 June 1940.

Following the 27 November 1941 “War Warning” message from the CNO, Admiral Hart finalized plans to move Houston, light cruiser Marblehead (CL-12), all 13 destroyers, and most auxiliaries of the Asiatic Fleet to locations farther south out of range of Japanese land-based bombers, leaving the defense of the Philippines to the 29 submarines. Hart also had the advantage of access to the decoded Japanese diplomatic traffic (Purple code), that Admiral Husband Kimmel at Pearl Harbor did not have. As intelligence sources increasingly indicated that war in the Far East was imminent, Hart executed the plan just before hostilities commenced. As a result, the Asiatic Fleet was initially spared the debacle that befell the U.S. Army Air Forces in the Philippines and Royal Air Force in Malaya on 8 December (7 December Pearl Harbor time). However, the elimination of U.S. and Allied capability to oppose Japanese air operations would have a severely debilitating effect on Allied naval operations for the duration of the campaign. For practical purposes, the Japanese would have uncontested control of the air, with the ability to bomb anywhere at will.

Houston and most other ships of the Asiatic Fleet withdrew to Darwin, Australia. Admiral Hart would eventually have to come south from the Philippines to Java in the Dutch East Indies via submarine. Houston soon became engaged in escorting convoys of reinforcements and supplies from Australia to the Dutch East Indies, all of which fell into the category of “too little, too late,” as the Japanese steadily advanced, taking airfields, port facilities, and oilfields on Borneo and other locations in the northern Dutch East Indies, extending the range of their bombers.

On 4 February 1942, Houston was part of a task force of ships under the command of Dutch Rear Admiral Karel Doorman, with the mission to oppose Japanese landings along the Makassar Strait between Borneo and Celebes Island. The Allied force came under concerted air attack that focused on Houston and Marblehead. The ship’s antiaircraft defenses were severely hampered as it was discovered that about 75 percent of U.S. 5-inch antiaircraft rounds were duds. Despite great ship handling, Marblehead was hit and severely damaged, which would force her to withdraw from the region.

In the intense air raid in the Flores Sea on 4 February 1942, lying on his back in the open to track Japanese aircraft so he could time maneuvers with bomb release, Rooks skillfully dodged dozens of accurately aimed bombs from about 50 bombers in multiple waves (some hitting within 10 feet of Houston). All missed, but the last bomb from the last plane was released at an errant angle and through sheer luck destroyed Houston’s after 8-inch turret, killing 48 men initially (more would die of wounds or would be lost ashore in hospital when Java fell), and reducing the ship’s main battery combat power by one third. Houston pulled into the port of Tjilitjap on the south coast of Java for initial repair, and the ship was battle-worthy within three days, departing on 10 February to meet up with a convoy coming north from Darwin. Given the option by Admiral Hart to withdraw his ship from the region for more extensive repairs, Rooks declined, because even damaged, Houston was the most capable ship the Allies had.

After on-loading more ammunition, Houston departed Darwin with the convoy on 15 February en route East Timor, which was under imminent threat of Japanese landings. The convoy came under heavy air attack on 16 February. This time, the 5-inch ammunition worked and Houston downed as many as seven of 44 attacking aircraft, drove others off, and disrupted the aim of even more. Houston was described as a “curtain of fire” as she radically maneuvered among the convoy, with the result being almost no damage to any of the Allied ships. However, the Allied command in Java determined it was too late to save Timor and the convoy, minus Houston, returned to Darwin, where most of it was destroyed by the surprise air strike by the Japanese carrier force on 19 February.

Having narrowly avoided being caught and destroyed in port, Houston nevertheless operated under constant threat from both land-based bombers and Japanese carrier aircraft. As it became apparent that the Japanese were massing forces for the assault on Java, the last major Allied-held island, Houston was assigned to an Allied force intended to intercept and destroy the Japanese landing force, although it was uncertain whether the Japanese intended to land at the eastern or western end of Java (actually it was both). The Allied force was again commanded by Rear Admiral Doorman and included Houston, British heavy cruiser HMS Exeter, Australian light cruiser HMAS Perth, and Dutch light cruisers HMNLS De Ruyter (flagship) and Java, accompanied by nine U.S., British, and Dutch destroyers.

The Allied force never had a real chance. With no air support, Doorman’s force was continuously dogged by Japanese reconnaissance aircraft, which enabled the Japanese to keep their troop transports out of harm’s way, and keep a blocking force of two heavy cruisers, two light cruisers, and 14 destroyers in between. Late in the afternoon of 27 February, the two forces engaged in what was the largest surface action since the Battle of Jutland in 1916. The initial phase consisted of a long-range gunnery duel in which both sides expended massive amounts of ordnance to little effect, and ineffective torpedo attacks by both sides. Houston claimed hits on a Japanese heavy cruiser, but Japanese records do not confirm this. Houston, in turn, was hit by two dud 8-inch rounds that did little damage. Finally, the Japanese scored a damaging hit on Exeter that caused her to veer out of formation, resulting in chaos due to the inability of the Allied ships to effectively communicate with each other.

At the end of the day, a Dutch and a British destroyer had been sunk. Damaged Exeter was escorted away by a Dutch destroyer, and the four U.S. destroyers were detached, as their torpedoes were expended. During the night, a British destroyer struck a “friendly” mine and sank, with the last destroyer detached to rescue survivors. The four remaining cruisers, with no escort, then resumed a northerly transit under cover of darkness in an attempt to reach the troop transports. However, Japanese reconnaissance by floatplanes was just as effective at night as during the day.

At about 2300 on 27 February, the two cruiser forces re-engaged. De Ruyter and Java were effectively blown out of the water by a salvo of Japanese “Long Lance” torpedoes, fired from a range the Allies did not think possible (hence the initial after-action reports blaming the hits on submarines). Rear Admiral Doorman went down with his ship. In accordance with standing orders from Doorman, Houston and Perth disengaged in order to exit the Java Sea and regroup south of Java. The Battle of the Java Sea had cost the Allies two light cruisers and three destroyers sunk, a heavy cruiser badly damaged, and about 2,300 crewmen killed in action. The Japanese lost about 36 sailors and suffered only minor damage in the debacle.

After the brief stop in Tanjung Priok, Houston and Perth were underway on the night of 28 February/1 March to exit the Java Sea via the Sunda Strait between Java and Sumatra, executing the pre-planned orders. With Perth in the lead (her skipper, the legendary Captain Hec Waller, was senior), the two unescorted cruisers encountered a Japanese blocking force, and in the initial exchange of gunfire discovered that they were unexpectedly in the midst of the main Japanese invasion force for Java. Perth opened fire first, followed immediately by Houston.

Although already critically low on ammunition, low on fuel, previously damaged, and with exhausted crews, both cruiser skippers chose to turn and attack toward the dozens of Japanese troop transports along the shore, which was the reason both ships had gone back into the Java Sea a week earlier. Although the chance of escape was slim, Captain Rooks placed duty over survival, and decided to sacrifice his ship dearly in an attempt to thwart the landing.

In the hours-long, close-quarters night melee that followed, both ships were surrounded on all sides by two Japanese heavy cruisers and numerous destroyers and smaller patrol craft, which fired 87 torpedoes at Houston and Perth. The Allied cruisers avoided numerous torpedoes, several of which hit and sank Japanese troop transports, including one with the Japanese commander of the invasion force embarked (Lieutenant General Hitoshi Imamura), who survived his swim ashore.

Both cruisers were ultimately hit by multiple torpedoes and countless shells, yet they still damaged numerous Japanese ships, fighting until they were out of ammunition, in the end firing star shells and exercise rounds directly at Japanese vessels until nothing was left. Perth went down first, and Houston fought on alone for 30 minutes as Japanese ships closed to within machine-gun range on all sides. Both Waller and Rooks were killed by enemy shellfire after finally giving the order to abandon ship. A Marine in Houston’s forward anti-aircraft platform fired his .50-caliber machine gun at the enemy until the ship slipped beneath the surface, her national ensign still flying high.

Of Houston’s 1,168 men, only 368 survived the battle. About 150 others known to have made it into the water were lost at sea due to wounds, drowning, hypothermia, or being carried by the current into the Indian Ocean. All other survivors were eventually captured by the Japanese. One hero of the sinking was chaplain Commander George Rentz, the oldest man aboard, who gave his life jacket to a wounded sailor (who initially refused to take it). Rentz would be the only Navy chaplain to be awarded a posthumous Navy Cross. However, until 291 survivors emerged from the hell of Japanese captivity at the end of the war, no one in the United States really knew what had happened in the Sunda Strait.

Captain Rooks was awarded a Medal of Honor while in missing-in-action status for his actions in the Battle of the Flores Sea and Java Sea; the period of action did not cover the Battle of Sunda Strait. Houston was awarded a Presidential Unit Citation after the war.

Medal of Honor citation:

The President of the United States, in the name of Congress, takes pride in presenting the Medal of Honor (deemed posthumously after the war) to Captain Albert Harold Rooks, United States Navy, for extraordinary heroism, outstanding courage, gallantry in action and distinguished service in the line of his profession, as Commanding Officer of the USS HOUSTON (CA-30), during the period 4-27 February 1942, while in action with superior Japanese enemy aerial and surface forces in the Netherlands East Indies. While proceeding to attack an enemy amphibious expedition, as a unit of a mixed force, HOUSTON was heavily attacked by bombers; after evading four attacks, she was heavily hit in a fifth attack, lost 60 killed and had one turret wholly disabled. Captain Rooks made his ship again seaworthy and sailed within three days to escort an important reinforcing convoy from Darwin to Koepang, Timor, Netherlands East Indies. While so engaged, another powerful air attack developed which by HOUSTON’s marked efficiency was fought off without much damage to the convoy. The commanding general of all forces in the area thereupon cancelled the movement and Captain Rooks escorted the convoy back to Darwin. Later, while in a considerable American-British-Dutch force engaged with an overwhelming force of Japanese surface ships, HOUSTON and HMS EXETER carried the brunt of the battles, and her fires alone heavily damaged one and possibly two heavy cruisers. Although heavily damaged in the actions, Captain Rooks succeeded in disengaging his ship when the flag commanding officer broke off the action and got her safely away from the vicinity, whereas one half of the cruisers were lost.

Like many combat award citations, Rook’s Medal of Honor citation is not completely historically accurate, which, however, does not detract from the valor of his action.)

The Fletcher-class destroyer DD-804 was named in honor of Captain Rooks. USS Rooks was commissioned in September 1944 and was awarded three battle stars in World War II for action at Iwo Jima and Okinawa. She was hit by shrapnel from a Japanese mortar at Iwo Jima, which killed one crewman. At Okinawa, Rooks fired 18,624 5-inch rounds in 87 consecutive days of shore bombardment, coming under direct kamikaze attack four times, and was credited with shooting down six Japanese aircraft and assisting in the destruction of many more. Rooks earned two battle stars during the Korean War, bombarding the North Korean ports of Songjin, Wonsan, and Chongjin. In 1962, she was transferred to the Chilean navy, serving as Cochrane until being scrapped in 1983.

Today, the Naval History and Heritage Command is working with the U.S. Embassy in Jakarta and the Indonesian government to protect the wreck of Houston from metal salvagers who have illegally removed the wrecks of almost every other Allied ship lost in the Java Sea. This has proved to be a protracted effort. (The Indonesian navy understands and is helpful, but it’s not their jurisdiction.) NHHC, along with Allied partners, also created a museum exhibit on the battle in Indonesia’s National Maritime Museum, which regrettably was subsequently destroyed in a fire.

In my opinion, Captain Rooks should have received a second Medal of Honor for his actions in the Battle of Sunda Strait. Although Albert Rooks faced a far tougher fight than John Paul Jones, Farragut, or Dewey, the U.S. Navy has no ship named after Rooks, although there is a water fountain at the Naval Academy dedicated in his honor.

____________

Sources include: Ship of Ghosts: The Story of USS Houston, FDR’s Legendary Lost Cruiser, and the Epic Saga of Her Survivors, by James Hornfischer, Bantam, 2007; Rising Sun, Falling Skies: The Disastrous Java Sea Campaign of World War II, by Jeffrey R. Cox: Osprey Publishing, 2014; In the Highest Degree Tragic: The Sacrifice of the U.S. Asiatic Fleet during World War II, by Donald M. Kehn, Jr., Potomac Books, 2017, The Fleet the Gods Forgot: The Asiatic Fleet in World War II, by Captain W.G. Winslow, USN (Ret.), Naval Institute Press, 1982; The Lonely Ships: The Life and Death of the U.S. Asiatic Fleet, by Edwin P. Hoyt, Jove Books, 1976; and Java Sea 1942: Japan’s Conquest of the Netherlands East Indies, by Mark Stille, Osprey Publishing, 2019.