H-006-2: "ISR" in the Battle of Midway

H-Gram 006, Attachment 2

Samuel J. Cox, Director NHHC

May 2017

**Revised and Updated 28 October 2019**

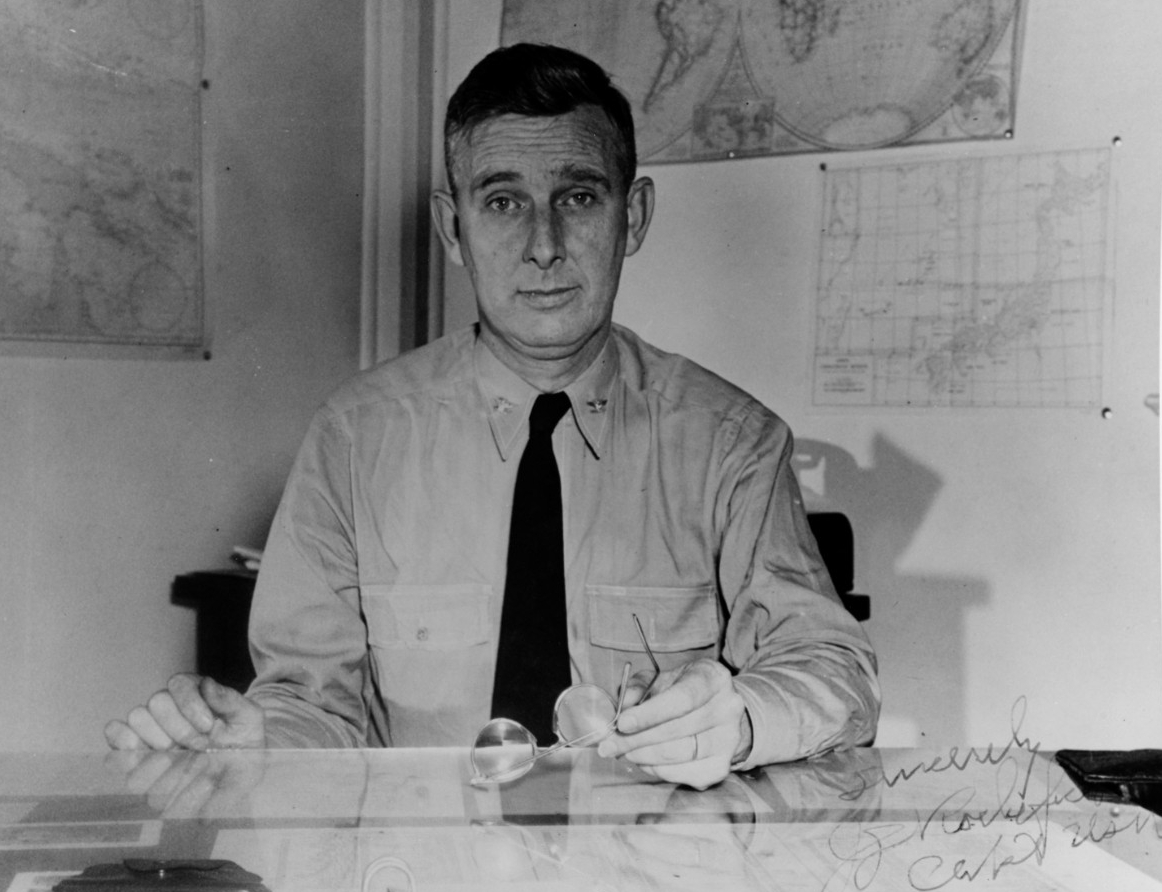

“To Commander Joe Rochefort must forever go the acclaim of having made more difference at a more important time than any officer in history.” At least, that’s what Captain Edward L. “Ned” Beach, Jr. (skipper of USS Triton [SSNR-586] during her around-the-world submerged voyage and author of Run Silent, Run Deep and other submarine classics) said. There is no question that Rochefort, commander of Station Hypo at Pearl Harbor, had profound effect on the outcome of the battle. He also had a lot of help, including from Japanese mistakes.

Station Hypo was a short-hand term used for the U.S. Navy’s code-breaking and signals intelligence operation, more formally known as the Combat Intelligence Unit, embedded within the naval communications station in the basement of the 14th Naval District Headquarters (commanded by Rear Admiral Claude Bloch), with Rochefort as officer-in-charge of communications. The 14th Naval District reported to the CNO, and Rochefort reported to OP-20G at Navy headquarters in Washington, DC. Officially, any intelligence developed by Hypo was to be sent to Washington (Station Negat) for analysis and dissemination. However, Rochefort had a long-established relationship and friendship with the Pacific Fleet intelligence officer, Lieutenant Commander Edwin Layton, when both underwent Japanese language training in Japan earlier in their careers. Rochefort routinely passed intelligence directly to Layton (to the consternation of Washington), who was only one of two officers accorded immediate and direct access to Admiral Nimitz at any hour.

Nimitz was a firm believer in the principle, first recorded by Sun Tzu and implemented by Julius Ceasar, that the commander should receive his intelligence directly from his intelligence sources, unfiltered by anyone else. Despite the fact that both Layton and Rochefort had been in the same jobs for the Pearl Harbor debacle, Nimitz recognized Layton’s unique talents and retained him, and made no effort to remove Rochefort (who technically didn’t work for Nimitz anyway). Nimitz told Layton that his job was to think like Admiral Yamamoto and provide estimates of what he thought the Japanese intended to do. Neither Layton nor Rochefort were intelligence officers (or code-breakers) —there was no such thing. Both were line officers who had had a few intelligence assignments among the line assignments necessary for promotion; intelligence work was generally considered non–career enhancing (junior officers assigned to an intelligence billet on battleships were known to be made the ship’s laundry officers), but was considered acceptable for a non–Naval Academy officer like Rochefort. Layton was a rare Annapolis line officer with exceptional talent, who had also willingly served in multiple intelligence assignments, and who, like Rochefort, spoke fluent Japanese.

The U.S. Navy code-breaking effort dated back almost to World War I, had progressed in fits and starts in the 1920s and 1930s, and had benefited greatly from Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) “black-bag jobs” such as breaking and entering a Japanese consulate to copy codebooks, etc. (which would be illegal now, and technically was illegal even then). By the time of Pearl Harbor, U.S. Navy and U.S. Army cryptologists (they took turns on alternate days) were breaking and reading the Japanese diplomatic code (called “Purple,” and the program “Magic”) faster than the Japanese embassy in Washington. Initial inroads were being made on breaking the Japanese navy general operating code, known at the time as the “5 num” code, and retroactively, as the JN-25 series (JN-25B at the time leading up to Pearl Harbor and Midway—changed to JN-25C a week before Midway). Rochefort was not the “code-breaker”—he was in charge of code-breakers. He had some previous tours in signals intelligence and code-breaking, and was well-suited for the assignment. The senior code-breaker in Station Hypo was actually Lieutenant Commander Carter Ham. At the time of Pearl Harbor, Hypo had been assigned to beat their heads against the wall trying to break the Japanese flag officers code (which was never broken), while Station Negat in Washington and Station Cast at Cavite, Philippines, worked on JN-25B.

After Pearl Harbor, Hypo was allowed to work on JN-25B and began to have success. Each raid by U.S. carriers on outlying Japanese garrison islands in early 1942 resulted in a flurry of Japanese communications (and communications security violations) tied to a specific, known event, which greatly aided the code-breaking effort. In conjunction with “traffic analysis” (analysis of message externals: to, from, precedence, length, etc.), this led to increasingly accurate estimates of Japanese force disposition and intent. However, even at best, the United States was only intercepting about 60 percent of Japanese naval communications, analyzing about 40 percent, and actually breaking and reading only about 10–15 percent, frequently only fragments of message internals (the “text”). Even when broken, the message was still in esoteric, highly technical, jargon-laden “navalese” Japanese, i.e., very difficult to translate by even the best linguists (coupled with the fact that very many geographic locations in the Pacific had multiple different names). So, it was not as if Nimitz had his own copy of the Japanese operations order before Midway. All he had was fragments, amplified by traffic analysis, other signals intelligence (intercepted clear voice), and other basic intelligence analysis techniques, and the experience and intuition of Layton.

Nevertheless, throughout the spring of 1942, Nimitz gained increasing confidence in the intelligence being provided by Layton and Rochefort. It was intelligence that led him to commit Yorktown (CV-5) and Lexington (CV-3) to counter the Japanese invasion attempt on Port Moresby, New Guinea, that resulted in the Battle of the Coral Sea on 7–8 May. On 12 May, Rochefort’s code-breakers got the first indications that the Japanese were planning a major operation in the Central Pacific, and Rochefort informed Layton that it was “really hot.” As more message traffic was intercepted, both Rochefort and Layton became convinced that Midway Island was the target, and they convinced Nimitz as well. Washington was not convinced, even though OP-20G/Negat and War Plans were analyzing the same intelligence.

Before Pearl Harbor and well into the spring of 1942, the intelligence situation in Washington, DC, was dysfunctional (contributing significantly to the disaster at Pearl Harbor). Four different directors of Naval Intelligence in a little over a year (none with intelligence background; most who didn’t want the job) didn’t help, nor did the constant reorganizations. The bitter, long-running bureaucratic (and resource) battle between naval communications and naval intelligence over who should own “communications intelligence” (and code-breaking) had a detrimental effect, and, at the time, naval communications was in the driver’s seat. After Pearl Harbor, the “father of U.S. Navy code-breaking,” Commander Laurance Safford, was removed and replaced as OP-20G by a line officer who had no experience in the subject. ONI was also involved in a bitter losing battle with the War Plans Division, under Rear Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner, in which ONI was barred from providing “assessments” of intelligence, since Kelly convinced CNOs Stark and King that assessments were a War Plans operational function and ONI was just supposed to provide the raw intelligence. Just prior to Pearl Harbor, Kelly officially assessed that the Japanese would not attack the United States, but would attack Russia instead. ONI held a different view. Also, Layton and Rochefort had experienced the chaotic period after Pearl Harbor in which a flood of bogus rumors (“RUMINT”) had paralyzed operational decision-makers. Station Negat on the other hand, “under new management” still chased after and reported numerous false and contradictory leads, providing “worst case” analysis to King.

Contrary to many books and movies, the famous “AF” gambit run by Rochefort was an attempt to get Washington to believe that “AF” stood for Midway, not to convince Nimitz. With an idea provided by Jasper Holmes, one of his staff, Rochefort had a message sent via secure underwater cable to Midway for the base to broadcast a phony radio message in the clear saying that its fresh water–making capability was broken. The Japanese intercepted the message and retransmitted the information, which was intercepted and broken by Hypo, confirming that “AF” stood for Midway. Still, many in Washington were unconvinced under the “this is too good to be true” principle. There were also a lot of good reasons why invading Midway Island seemed to make no sense. In fact, the Japanese Naval General Staff had made the same arguments in a losing battle against Yamamoto’s plan. There was also considerable argument about the wisdom of basing a plan around Japanese intent rather than Japanese worst-case capability, and that it all might be an elaborate Japanese deception. Eventually CNO King came around after ordering an assessment be provided to him directly from Rochefort.

On 17 May, convinced that Midway was the main Japanese objective, Nimitz sent an eyes-only (and “no CNO”) message to Vice Admiral William Halsey, embarked on USS Enterprise (CV-6), directing him to deliberately expose Enterprise and TF-17 to Japanese reconnaissance aircraft in the vicinity of the Gilbert Islands, which Halsey dutifully did. This accomplished several objectives. By “blowing” Halsey’s operation, Nimitz had a pretext to recall Enterprise and Hornet to Pearl Harbor (the damaged Yorktown was already en route Pearl Harbor for repair after Coral Sea). This way he could concentrate his forces at Midway and get King off his back about keeping a carrier in the South Pacific to counter a possible Japanese thrust against the Fiji/Somoa area, which deeply concerned King. It also fooled the Japanese into thinking at least one of the U.S. carriers was in the South Pacific, which would enable the Midway operation to defeat the U.S. carriers piecemeal.

On 18 May, Nimitz directed Layton to provide his best estimate of where and when the Japanese carriers would first be detected. Layton provided the estimate on 27 May (see H-006-1: Battle of Midway—Overview) and the same day Nimitz issued OPLAN 29-42, directing Enterprise and Hornet to proceed to the vicinity of Midway, and Yorktown to follow suit as soon as temporary repairs were complete at Pearl. Nimitz also directed that Task Force ONE (TF-1), the battleships, several of which had been repaired after Pearl Harbor, to remain on the West Coast, to the dismay of TF-1 commander Vice Admiral William S. Pye (and to some degree CNO King) because they were too slow, too vulnerable, and used up too much fuel.

Nimitz also directed that Midway Island’s defenses be significantly increased, to include additional reconnaissance aircraft. By early June 1942, the 127 aircraft based on Midway Island included 31 PBY Catalina flying boats, a few rigged to carry a torpedo. Seventeen USAAF B-17 bombers also provided additional reconnaissance capability. The PBYs began to fly missions out to 700 miles from Midway, and, on 3 June, sighted the Japanese minesweeper group coming from Guam and also the Japanese invasion/occupation force, which was also sighted and reported by a U.S. submarine. B-17s also bombed the invasion force, albeit with no hits (although many were claimed). Thick fog to the northwest of Midway covered (and delayed) the Japanese carrier force.

Before dawn on 4 June, 15 B-17s launched to attack the invasion force again, while 22 PBYs commenced reconnaissance flights, mostly to the northwest. Yorktown, at “Point Luck” northeast of Midway, also launched 10 SBD Dauntless dive-bombers on a relatively short 100–nautical mile search pattern to assure Rear Admiral Fletcher that no Japanese carriers were in close proximity.

At 0530, a PBY flown by Lieutenant Howard P. Ady sighted Japanese ships northwest of Midway and issued a sighting report at 0534. At 0545 another PBY, flown by Lieutenant William Chase sighted the inbound Japanese air strike and reported “many aircraft heading Midway.” Several minutes later, at 0552, Chase sighted two of the Japanese carriers. Midway radar detected the incoming strike at 0553. Word of the Japanese carriers reached Fletcher, Spruance, and Nimitz shortly after 0600 (almost right on Layton’s estimate).

Japanese ISR at Midway

The Japanese navy had a relatively robust intelligence capability, in particular a very effective shipboard radio intelligence capability that could intercept and translate U.S. clear voice communications in near–real time, providing useful tactical information to Japanese commanders even in the heat of battle. The Japanese were also relatively proficient at traffic analysis. Japanese radio intelligence picked up and reported the greatly increased volume of high-precedence U.S. messages in the days before Midway, but the significance was lost on senior Japanese commanders, who remained fixated on the plan and the belief that it could not have been compromised. Japan’s extremely long-range reconnaissance seaplanes were also very capable, although also very vulnerable to U.S. fighters. The Japanese, however, were not able to break U.S. Navy codes (but not for want of trying), which left them at a significant disadvantage. Also, the small but effective Japanese human intelligence network on Oahu was rolled up very quickly after Pearl Harbor, and Japanese-Americans (Nisei) in Hawaii (or the mainland United States) never engaged in espionage as feared. (In fact, the official ONI assessment was that the Nisei were not a threat and recommended against internment, but the Navy was overruled by the Army and President Roosevelt.)

Without a human intelligence network in Hawaii, the Japanese plan depended on reconnaissance of Pearl Harbor by flying boat, and a line of submarines between Hawaii and Midway. Both operations failed miserably. Operation K was to be a reconnaissance of Pearl Harbor by two Kawanishi H8K Type 2 “Emily” long-range flying boats from the Marshall islands, which would refuel from submarines at French Frigate Shoals (midway between Oahu and Midway Island), specifically to determine the whereabouts of the U.S. carriers. The Japanese had done this before. On the night of 3–4 March, two Kawanishi flying boats conducted a reconnaissance/bombing mission over Pearl Harbor. Station Hypo provided advance warning of the operation, but night and overcast prevented intercept, but also precluded reconnaissance or accurate bombing by the Japanese. One of the flying boats dropped its bombs through the overcast onto the foothills near the Punchbowl. No one knows where the other plane’s bombs went. (This is also the known as the “second air raid on Pearl Harbor.”) The Japanese tried another similar operation with one flying boat on 9–10 March, but this was also compromised, and the flying boat was shot down by a Marine Corps fighter from Midway Island. The Japanese did not catch on that this might be a bad idea.

When Operation K was implemented, the Japanese submarine sent to conduct reconnaissance of French Frigate Shoals discovered a U.S. seaplane tender and destroyer camped out there. The U.S. ships were sent there deliberately by Nimitz to keep the Japanese from doing exactly what they were trying to do. The two refueling submarines I-121 and I-123 lingered for a couple days hoping the U.S. ships would go away, but on 31 May, Operation K was cancelled, depriving the Japanese of critical intelligence on the U.S. carriers. The implication that the United States might be forewarned was also ignored by senior Japanese commanders.

The Japanese submarine reconnaissance line was an even bigger failure. The plan called for seven submarines to be stationed along a line north of the Hawaiian Islands and seven more south of the Hawaiian Islands, at the midpoint between Midway and Oahu, to detect and report the transit of U.S. carriers. However, most of the submarines committed were among the oldest and least reliable in the Japanese Navy, although this was known, and ignored by senior Japanese commanders. What Yamamoto and Nagumo did not know was that the entire submarine force had been held back by mechanical difficulties of several boats, and none of the submarines reached station when they were supposed to. The politically connected and imperial family–related Rear Admiral Marquis Teruhisa Komatsu, commander of Sixth Fleet (submarines), decided not to tell anyone about the late departure. Actually, it wouldn’t have made any difference. Even if the submarines had arrived on schedule, all three U.S. carriers had already gone past.

The only Japanese submarine to distinguish itself in a reconnaissance role was I-168 (which also later sank Yorktown). I-168 observed Midway Island for several days before the battle, accurately reporting that Midway’s defenses had been greatly beefed up, that the island was on high alert, and that numerous U.S. reconnaissance aircraft were flying missions out to extreme range, based on how long they were airborne. This information was also filed under “gee, that’s nice” by Japanese commanders.

On the morning of 4 June, the Japanese carrier force executed a woefully inadequate search plan. Like the Americans, the Japanese knew very well from pre-war exercises that whichever carrier force found the other one first had a decisive advantage. Despite this, the Japanese much preferred not to “waste” carrier-based strike aircraft on reconnaissance, preferring to rely instead on long-range land-based aircraft and catapult-launched floatplanes from battleships and cruisers. Relying on land-based aircraft did have an operational security advantage, in that reconnaissance by land-based aircraft did not give away the presence of an aircraft carrier. This, however, was not an option for the Japanese at Midway. It was an option for the U.S., which is why Rear Admiral Fletcher kept his morning reconnaissance flight close to his carriers (within 100 miles) so as to not give away is presence, relying on the Midway-based PBY Catalina’s to find the Japanese carriers. Given the complexity of the Japanese plan, floatplane capable escort ships were spread thin. Within the Japanese carrier force, the two battleships, Haruna and Kirishima, carried three floatplanes (of limited range) and the two cruisers Tone and Chikuma had been built to carry five longer-range floatplanes.

Just before daybreak on 4 June, the Japanese launched seven aircraft to conduct a search of about a 200-degree sector, which resulted in Swiss cheese coverage, particularly given the cloud conditions to the east-northeast, which is where the U.S. carriers were. Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo and his staff understood that the search plan was weak, but accepted it. They still believed they had the element of surprise, and they were fixated on maximizing the first strike on Midway Island. They also still believed that it was unlikely any U.S. ships would be in the area, and, if there was a carrier, there wouldn’t be more than one. The Japanese believed that Lexington (CV-2) had been torpedoed and sunk by a submarine in January (actually, it was Saratoga [CV-3]—which was only damaged). They also believed they had sunk both Yorktown and Saratoga (because they’d already “sunk” her sister Lexington) at Coral Sea. One carrier had been spotted near the Gilberts (either Enterprise [CV-6] or Hornet [CV-8]) and, although the Japanese didn’t know for sure where Ranger (CV-4) and Wasp (CV-7) were, they had last been located in the Atlantic. That left one U.S. carrier to oppose the Midway strike, and the Japanese remained convinced, based on no evidence, that this carrier was cowering in Pearl and would need to be drawn out to fight. Their complacency, a symptom of “victory disease” (the sense of their own invincibility coupled with the fatigue of six months of non-stop operations), would prove fatal.

Tone’s No. 4 scout (an Aichi E13A Type 0 “Jake”) launched late, due to reasons that still remain unclear, to fly the No. 4 search line. Its late launch has been cited by many historians as a key factor in the Japanese defeat since it did not detect the U.S. carriers until it was too late. Actually, Chikuma’s No. 1 scout, launched on time, and flying No. 5 search line, should have seen TF-17 at approximately 0615, but did not due to clouds or other factors that remain unclear. Even if Chikuma No. 1 had found the U.S. carriers at 0615, it was already too late for Nagumo to launch the reserve strike (107 aircraft , armed with anti-ship weapons) before the U.S. carriers started launching. Nagumo lost the battle as soon as he launched the first strike on Midway Island (in accordance with Yamamoto’s plan) without knowing the U.S. carriers were in the vicinity. Had Chikuma No.1 sighted the U.S. carriers earlier, the best Nagumo could have done would have been to trade blows (a typical outcome of pre-war U.S. exercises). If Tone No. 4 had launched on time and flown the prescribed route, she would have missed the U.S. carriers, and the first indication Nagumo would have had of them was the 15 TBDs of Hornet’s Torpedo Squadron EIGHT.

Rochefort’s reward for his success was to be recalled to Washington by OP-20G on a pretext, never to return to Hypo, and to be given command of a floating dry dock. Nimitz’ recommendation that Rochefort be awarded the Distinguished Service Medal was denied by CNO King on the recommendation of Rochefort’s Washington chain of command, which then took credit for having broken the Japanese code and predicted the Midway operation, even though they had done no such thing. Nimitz tried to get King to reconsider, but got sidetracked by having a world war to run. Not until intelligence records became declassified in the 1970s did the real story become known to the public. And, not until after a years-long campaign by Rear Admiral Donald “Mac” Showers, who had been an ensign in Station Hypo with Rochefort, was Rochefort posthumously awarded the Navy Distinguished Service Medal by President Ronald Reagan in 1985.