H-021-3: U.S. Navy in World War I—First Naval Aviation Medal of Honor, First Ace, Railway Artillery, Heaviest Loss, and Only Surface Action, August–October 1918

H-Gram 021, Attachment 3

Samuel J. Cox, Director NHHC

September 2018

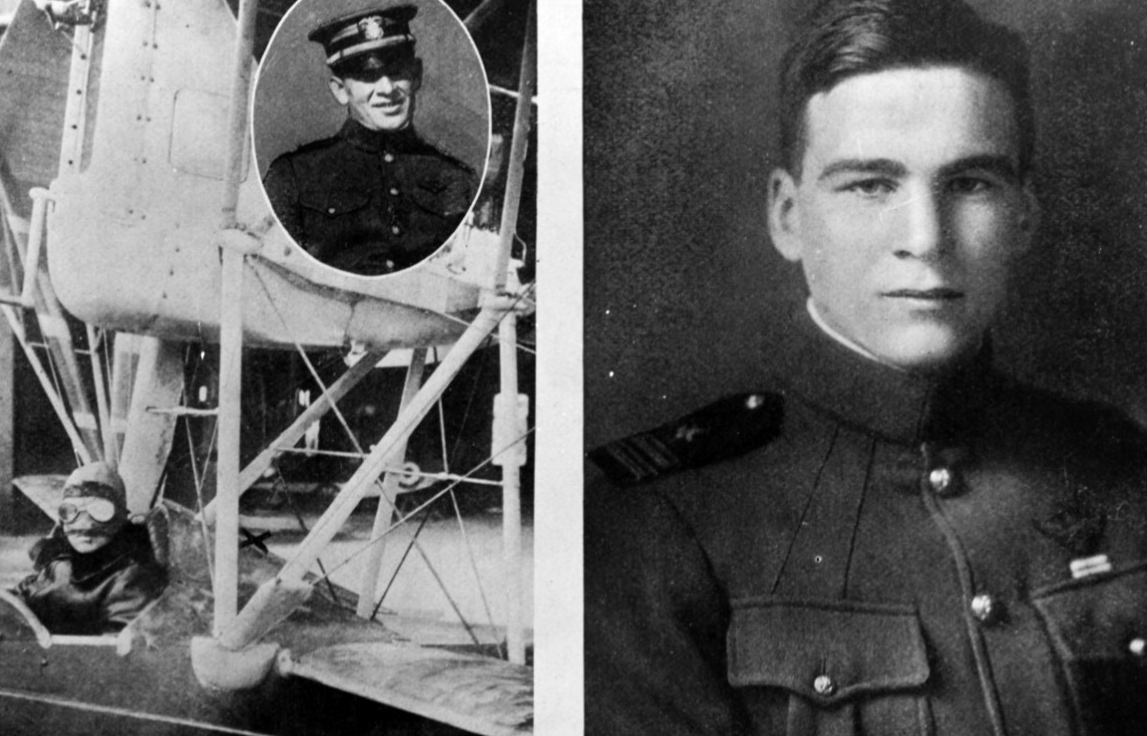

First Naval Aviation Medal of Honor

Enlisted Pilot Charles Hazeltine Hammann, U.S. Naval Reserve Force (Naval Aviator No. 1494), became the first U.S. aviator—of any service—to receive the Medal of Honor for his actions on 21 August 1918 off the Austro-Hungarian coast (now Croatia) where he rescued downed naval aviator Ensign George M. Ludlow (Naval Aviator No. 342). The U.S. Army had two aviators who were Medal of Honor recipients during the conflict: Captain Eddie Rickenbacker for his actions on 25 September 1918 and First Lieutenant Frank Luke Jr. (posthumously) for his actions on 29 September 1918. U.S. Marine Corps pilot Second Lieutenant Ralph Talbot received the nation’s highest honor for actions on 8 October and 14 October 1918, but would be killed in a crash before receiving it.

At the invitation of the Italian government, which was on the Allied side during World War I, the U.S. Navy established a naval air station co-located with an Italian seaplane base at Porto Corsini, about 50 miles from Venice. On the night of 24 July 1918, planes of the Austro-Hungarian Empire (Germany’s ally) bombed the station, fortunately with little damage. Nevertheless, the U.S. base became operational, and was the only U.S. naval air station on the Adriatic. On 21 August 1918, five U.S. Navy Macchi M.5 seaplanes—a small single-seat seaplane fighter built by the Italians—flew their first combat mission, escorting two Italian M.8 seaplane bombers on a leaflet-dropping mission over the heavily defended Austro-Hungarian port and naval base of Pola. Five land-based Austro-Hungarian Albatross fighters and two seaplanes engaged the escorting U.S. aircraft.

During the dogfight near Pola, the M.5 flown by Ensign George Ludlow was hit and so badly damaged that Ludlow had to set down in the Adriatic about three miles off the coast of Pola, where he risked being captured (the Austrians had threatened to execute any downed aviators flying missions over their territory). As Ludlow took steps to scuttle his aircraft, Enlisted Pilot Charles Hammann landed his seaplane on the water alongside Ludlow. Although Hammann’s seaplane had also been damaged in the dogfight and had not been designed to carry the weight of two people, Hammann brought Ludlow on board as Ludlow’s aircraft sank. Barely able to get the plane airborne, Hammann nevertheless succeeded in doing so while avoiding additional Austro-Hungarian search planes. He made his way back to Porto Corsini, where his plane sank after landing due to the excessive weight. Hammann would receive the Medal of Honor for his actions along with an Italian Medaglia a’Argento al Valore Militare. Ludlow was awarded the Navy Cross. Hammann would also be commissioned an ensign in October 1918, but would unfortunately be killed in a crash of an M.5 at Langley, Virginia, on 14 June 1919. On 15 September 1918, Ensign Louis J. Bergen, USNRF, and Gunner Thomas L. Murphy, USN, were killed in an accidental crash of an M.8 at Porto Corsini.

The destroyer USS Hammann (DD-412) would be named in honor of Charles Hammann, and would be sunk by the Japanese submarine I-168 while rendering alongside assistance to the stricken carrier USS Yorktown (CV-5) on 6 June 1942 following the Battle of Midway, with the loss of more than 80 of Hammann’s crew. A subsequent Edsall-class destroyer escort (DE-131) would be named after Hammann and serve at the end of World War II.

Ensign Hammann’s Medal of Honor citation reads:

“For extraordinary heroism as a pilot of a seaplane on 21 Aug 1918, when with three other planes Ens. Hammann took part in a patrol and attacked a superior force of enemy land planes. In the course of the engagement which followed the plane of Ens. George M. Ludlow was shot down and fell in the water 5 nm. off Pola. Ens Hamman immediately dived down and landed on the water close alongside the disabled machine and took Ludlow on board. Although his machine was not designed for the double load to which it was subjected, and although there was danger of attack by Austrian planes, he made his way to Porto Corsini.”

First U.S. Navy Ace

On 24 September 1918, Lieutenant David Stinton Ingalls, U.S. Naval Reserve Force (Naval Aviator No. 85), shot down six German aircraft in six weeks, becoming the U.S. Navy’s first ace—and only ace of World War I—on 20 September when he shot down a German Fokker D.VIII fighter. Flying a Sopwith Camel, and assigned to Royal Air Force No. 213 Squadron, Ingalls sighted a two-seat German Rumpler reconnaissance aircraft over Nieuport, Belgium, and, in conjunction with another Sopwith Camel, shot it down. Ingalls would be awarded the Distinguished Service Medal—at that time a higher award than a Navy Cross—a British Distinguished Flying Cross, and a French Legion of Honor. Ingalls would shoot down a total of five German aircraft and a balloon during the war. (Although an observation balloon itself was an easy target, German balloons were invariably heavily defended by ground anti-aircraft fire and were actually very dangerous targets, which made U.S. Army Air Corps pilot Frank Luke Jr.’s downing of four balloons in one day, at the cost of his life, worthy of the Medal of Honor.)

Ingalls entered Yale University in 1916, learning to fly as part of the civilian 1st Yale Unit, which transitioned into the U.S. Naval Reserve Flying Corps. Ingalls enlisted on 26 March 1917—just before the outbreak of war—and was promoted to lieutenant junior grade upon completion of initial training in September 1917. He was ordered to Europe in September 1917 and trained with both the British in fighters and French air force in bombers before winding up flying Sopwith Camel fighters. Royal Air Force No. 213 Squadron, which flew from Dunkirk, France, escorted bombers attacking German submarine bases on the coast of Belgium at Bruges, Zeebrugge, and Ostend. The intensity of air combat on the Western Front was such that in one ten-day period in May 1918 the Royal Air Force lost 478 aircraft; the average life expectancy of a pilot was measured in days. Just to survive was a major accomplishment.

On 11 August 1918, after a long scoreless period, Ingalls and his British flight leader downed a German Albatross fighter flying an observation mission over the port of Dixmunde, Belgium. Two nights later, Ingalls participated in a nighttime bombing and strafing mission on the airfield near Zeebrugge, during which 38 German aircraft were destroyed on the ground. On 21 August 1918, Ingalls shot down a German LVG two-seat reconnaissance aircraft, sharing credit with another Camel pilot. On 15 September, Ingalls participated in another bombing and strafing mission of a German airfield, during which his bombs destroyed several parked aircraft. While returning to base, he and another Camel pilot downed a Rumpler reconnaissance aircraft. On 18 September, Ingalls and two other pilots downed a German observation balloon. On the 20 September, Ingalls lost his engine and nearly crash-landed in a field behind enemy lines, but his engine restarted at the last moment. While returning to base, Ingalls surprised a Fokker D.VIII fighter from behind and shot it down, his only solo kill. On 26 September, he shared credit for downing his sixth aircraft (counting the balloon). Although Ingalls is considered an ace, all his kills but one were shared credit, usually with other British aces.

Ingalls was released from Navy service in January 1919, going on to a career in law, journalism, politics, and government, including serving during the Hoover administration as the Assistant Secretary of the Navy for Air. During his tenure in this position, Ingalls tripled the number of Navy aircraft and was instrumental in establishing fully deployable carrier task forces.

(Sources: United States Naval Aviation, 1910–2010, Vol. I: Chronology by Mark L. Evans and Roy A. Grossnick; and America’s Sailors in the Great War: Sea, Skies, and Submarines by Lisle A. Rose.)

(Back to H-Gram 021 summary)

U.S. Navy Railway Guns: A Case Study in Rapid Prototyping and Acquisition

On 6 September 1918, the 14-inch, 50-caliber Mark IV naval rifle of Battery 2, commanded by Lieutenant Junior Grade E. D. Duckett, USN, of the U.S. naval railway gun unit opened fire on a key German railway hub in France at a range of over 20 miles. The firing marked the combat debut of a weapon that had been conceived, designed, built, and shipped in only a few months. The firing position at Compiègne was the same spot where the Germans would later sign an armistice ending the war on 11 November 1918—and where France would surrender in World War II. The five batteries—one gun each—of the naval railway unit would go on to fire 782 14-inch rounds on 25 occasions at strategic targets far behind German lines before the war ended. In fact, Battery 4 fired her last round timed to impact seconds before the armistice cease-fire was to go into effect at 1100—possibly, the last shot to impact before the war ended.

The German’s got the jump on the Allies in building rail-mobile long-range artillery that could hit targets very accurately far behind Allied lines without risking vulnerable bomber aircraft—or the even more vulnerable Zeppelin airships. During 1917, German railway guns regularly bombarded the key port of Dunkirk, France, which was critical to supplying British troops on the Western Front, among other targets. At the peak of the German’s spring 1918 offensive, their largest railway gun—often erroneously referred to as “Big Bertha” (a different gun)—lobbed shells into the city of Paris.

On the Allied side, the U.S. Navy was the first to develop a similar weapon system. Rear Admiral Ralph Earle, chief of the U.S. Navy Bureau of Ordnance and for whom the Naval Weapons Station Earle, New Jersey, is named, led the development of requirements for the railway guns and for the new type of mine used in the North Sea Mine Barrage. Design work on the weapon commenced at the end of December 1917 and concluded in late January 1918. The first weapons were built and ready to ship by April 1918, as the situation in France became increasingly desperate with the rapid advance of the German army that would eventually run out of steam just short of Paris. The commander of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF), Lieutenant General John J. Pershing, wanted the weapons delivered to France as fast as possible. The primary reason for the delay between when the weapons were ready to ship and when they went into action was uncertainty as to which ports would still be in Allied hands given the rapid German advance. Efforts by the other Allies, and the U.S. Army, to develop similar long-range rail artillery were generally not completed or deployed before the armistice.

Each of the initial five batteries consisted of one 14-inch naval rifle on a special railroad car. As the newest U.S. battleships were being armed with 16-inch guns, there were a number of spare 14-inch guns that were readily available for use. The guns were assembled at a naval gun factory at the Washington Navy Yard and mated with railway carriages at the Baldwin Locomotive Works and Standard Steel Car Company in Pennsylvania. In addition to the gun car, each battery included a locomotive, two ammunition cars with 25 rounds each, two construction materiel cars, a crane, fuel, a workshop, berthing, kitchen and medical cars, all under the command of a Navy lieutenant. The five batteries were each independently mobile, but under the overall command of Rear Admiral Charles P. Plunkett, who had his own staff train. The entire unit had about 25 officers and 500 enlisted personnel.

Due to the limited traverse of the gun, a railway siding would have to be quickly constructed that pointed in the direction of the intended target, hence the construction cars. In addition, to elevate the gun, a pit had to be dug underneath the rail bed, and the rails removed due to the width of the gun breech. The Mark II components to the gun fixed these issues, but they were not ready before the war ended. The weight of the gun carriage greatly exceeded the rated capacity of French railroads, so the trains were constrained to a speed of only about five miles per hour. The mobility of the trains was their best defense, but they were subject to German aerial observation and occasional air attack and counter-battery fire. However, only one U.S. Navy crewman was killed as a result of enemy action and a number wounded.

An example of the Navy railway gun is on display at the Washington Navy Yard. This Mark I gun was used for testing in the United States and is not one of the five that deployed to France. Those were later turned over to the U.S. Army, with some serving as coastal artillery between the world wars before eventually being scrapped.

(Source: NHHC Document, United States Naval Railway Batteries in France. )

(Back to H-Gram 021 summary)

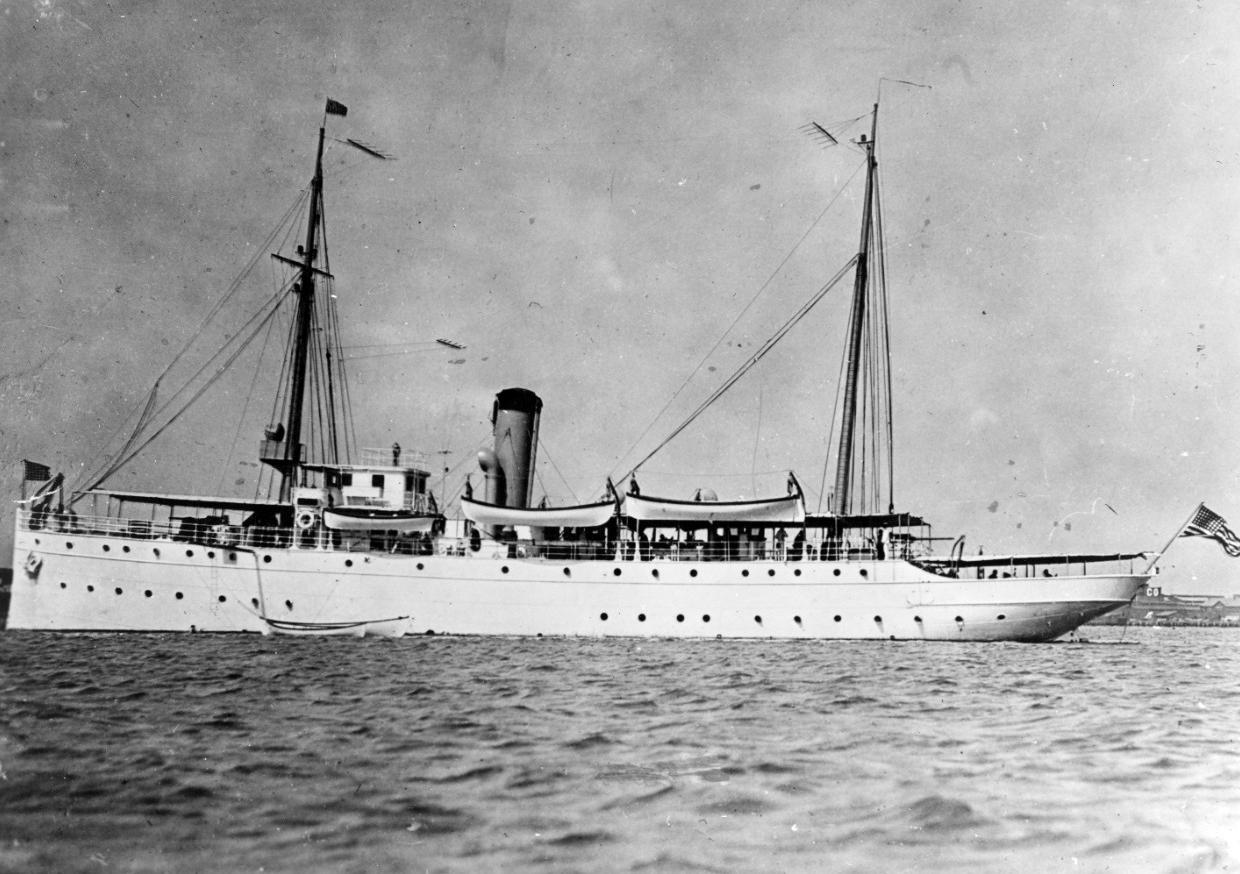

Semper Paratus: Sinking of USS/USCGC Tampa, 26 September 1918

Although the largest U.S. warship lost in World War I was the armored cruiser USS San Diego (ACR-6) in July 1918—see H-Gram 019—the largest loss of life in combat occurred when U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Tampa—operating under U.S. Navy control with a Coast Guard crew—was torpedoed and sunk by German submarine UB-91 in the Bristol Channel on the evening of 26 September 1918 with the loss of all 131 personnel aboard.

Originally commissioned in 1912 as the cutter Miami in the U.S. Revenue Cutter Service in Arundel Cove, Maryland, the Tampa was one of the first U.S. ships to participate in the International Ice Patrol following the sinking of the liner Titanic by an iceberg in 1912, and she alternated deployments between Tampa, Florida, and the North Atlantic. On 28 June 1915, the Revenue Cutter Service merged with the U.S. Lifesaving Service to create the modern U.S. Coast Guard. In February 1916, Miami was renamed Tampa. Upon the entry of the United States into World War I, the U.S. Coast Guard and its 25 seagoing cutters were subordinated to the U.S. Navy on 6 April 1917. (In message traffic during the war, the ship was referred to as USS Tampa.) Following replacement of her older weapons with two 3-inch guns, a pair of machine guns, and depth-charge racks and projectors, she and five other Coast Guard cutters were ordered to proceed to Gibraltar, arriving on 27 October 1917 and forming Squadron 3 of Division 6 of the Atlantic Fleet Patrol Forces.

From October 1917 until she was sunk, Tampa escorted 19 convoys with 420 ships between Gibraltar and the Irish Sea and the southern coast of England, during which only two ships in those convoys were lost to German U-boats. Although Tampa fired on several possible submarine targets, there were no confirmed interactions between her and German submarines prior to 26 September 1918. However, under the command of Captain Charles Satterlee, USCG, she did receive very high marks for her high state of readiness and morale, despite being underway over 50 percent of the time she was stationed at Gibraltar.

In the late afternoon of 26 September 1918, Tampa detached from escort of northbound 32-ship Gibraltar convoy HG-107 as the convoy entered the Irish Sea. Proceeding independently into the Bristol Channel heading for a port in Wales at about 2015, Tampa was hit by one torpedo fired by UB-91, commanded by Kapitänleutnant Wolf Hans Hertwig, on his second war patrol.

UB-91 was a comparatively small Type-UB III coastal submarine—about 500 tons, 182 feet, crew of three officers and 30 enlisted personnel, speed 13 knots surfaced and 7 knots submerged, armed with one 4.1-inch deck gun, four bow torpedo tubes, one stern tube, and 10 torpedoes. The class was pretty successful: 96 were built and 95 commissioned, and were responsible for sinking 507 ships, with 37 UB III’s lost in combat and four to accidents. UB-91 sank four ships, with Tampa being the second.

According to UB-91’s log and Hertwig’s account, UB-91 was lined up for a bow shot on Tampa when she zigged, and he wound up taking a shot with the single stern tube at a range of about 500 yards. The torpedo hit Tampa on her port side amidships. At the time, visibility was fading in the darkness, and Hertwig reported the ship only as a dark shape. About two minutes after the torpedo hit, a second very large explosion and flash of light occurred, which may have been Tampa’s depth charges going off. All 111 Coast Guard personnel (11 officers and 100 enlisted), four U.S. Navy personnel (three officers and one enlisted), 11 Royal Navy ratings, and five Admiralty Dockyard civilian workers aboard were killed. Two enlisted U.S. Coast Guardsmen missed ship’s movement at Gibraltar due to being sent to the medical clinic. Hertwig actually came to the surface and searched for survivors, but found nothing. Subsequent searches by Allied ships located one unidentified body, while three others were eventually recovered, one at sea and two washed ashore. Captain Satterlee was posthumously awarded the Navy Distinguished Service Medal. Tampa is named in the second verse of the Coast Guard song “Semper Paratus—Always Prepared”—in the roll of honor. In 1999, the 111 Coastguardsmen who perished on Tampa were awarded Purple Hearts. As a result of the sinking of Tampa, the U.S. Coast Guard suffered proportionately the largest casualties of all U.S. services during World War I.

UB-91 continued her patrol, sinking two more ships, including the Japanese-flag Hirano Maru on 4 October 1918, during which 292 of 320 people aboard were lost. The submarine returned safely to Germany in time to be surrendered at the armistice. Of note, the largest loss of U.S. Navy life during World War I was 306 aboard the collier USS Cyclops (AC-4), which disappeared without a trace in March 1918.There is no evidence her loss was a result of enemy action. The worst loss of life aboard a ship by any nation during World War I was the Italian-flag transport Principe Umberto, which was torpedoed by the Austro-Hungarian submarine U-5 on 8 June 1916 with the loss of 1,926 troops and crew of 2,821 aboard. The U-5, one of only four operational Austro-Hungarian submarines at the start of the war, had previously been commanded by George Ritter von Trapp, who sank the French armored cruiser Leon Gambetta—684 of 821 men lost—on 26 April 1915 in the Strait of Otranto. Von Trapp was the pater familias of the famous Von Trapp family singers, and is the Austrian sea captain depicted in the movie The Sound of Music.

(Sources: “The Last Full Measure of Devotion: Captain Charles Satterlee, Class of 1898, Last Commanding Officer of the USCGC Tampa Sunk Over 94 Years Ago This September” by Robert M. Pendleton, Foundation for Coast Guard History; NHHC Dictionary of American Fighting Ships—DANFS—and Uboat.net.)

(Back to H-Gram 021 summary)

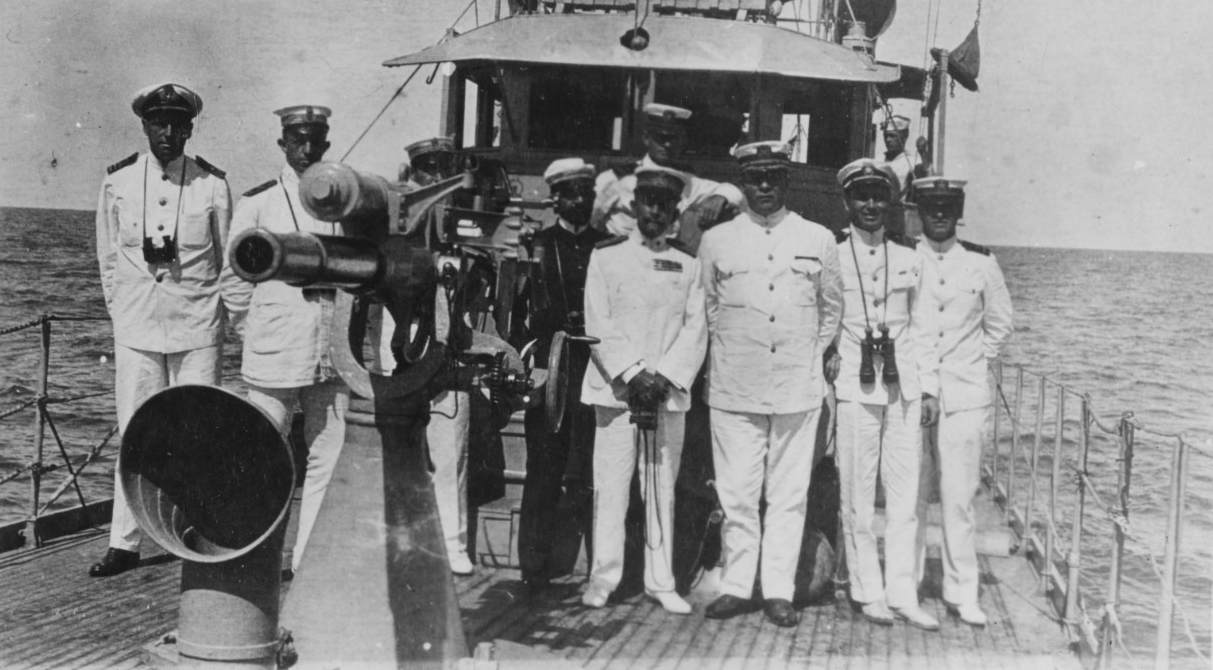

The Only World War I U.S. Navy Surface Action: The Second Battle of Durazzo, 2 October 1918

The only actual surface action that U.S. Navy forces participated in during World War I was known as the Second Battle of Durazzo—present-day Durres, Albania—in the Adriatic on 2 October 1918. Twelve U.S. Navy submarine chasers under the command of Captain Charles P. Nelson, USN, participated in a combined Italian, British, and Australian naval force against ships, submarines, and shore batteries of the Austro-Hungarian Empire near the port of Durazzo. The 12 sub chasers provided screening services for an Allied force consisting of an Italian battleship, 3 Italian armored cruisers, 3 Italian light cruisers, 5 British light cruisers, 14 British destroyers, 2 Australian destroyers, 8 Italian torpedo boats (and a partridge in a pear tree). The Austro-Hungarian naval force mostly bugged out before the battle commenced, leaving only two destroyers, a torpedo boat, and two submarines to oppose the Allies, and even they all managed to escape, albeit damaged. A heavy Italian bombardment by the armored cruisers directed at the naval base mostly succeeded in leveling a large part of the adjacent city. So, there is good reason why you probably never heard of this battle. Nevertheless, the U.S. sub chasers were subjected to pretty intense enemy fire and acquitted themselves very well, inflicting significant damage on the two Austro-Hungarian submarines engaged.

In September 1918, an Allied force that had been bottled up in a quagmire at Salonika, Greece, on the Aegean Sea for well over a year finally started making progress, advancing into Macedonia and knocking Bulgaria—a German ally—out of the war. The French commander of the operation requested a naval action to prevent Austro-Hungarian reinforcements or supplies from arriving via Durazzo, the major Albanian port on the Adriatic. The Italian navy agreed, somewhat reluctantly, to the request and supplied the major capital ships as well as the commander, Rear Admiral Osvaldo Paladini. The American sub chasers, which had arrived in Corfu, Greece in June 1918 to assist in trying to prevent Austro-Hungarian and German U-boats from getting in and out of the Adriatic via the Strait of Otranto, were invited to participate.

The battle began with an early-morning air attack on Austro-Hungarian troop concentrations and shore batteries by Italian and British aircraft. While the Italian battleship stood off as a covering force, the Italian and British cruisers moved in close to the port to commence a bombardment after the American sub-chasers found a path through the offshore mine fields, coming under fire from shore batteries as they did so, without damage. Once through the minefields, some of the American sub chasers and Allied destroyers and torpedo boats were tasked to engage the two Austro-Hungarian destroyers and torpedo boat in the port. The Austro-Hungarian ships spent the first part of the battle steaming around the harbor, dodging torpedoes and shellfire—the torpedo boat was hit by a dud torpedo—before they made their escape to the north.

The three Italian armored cruisers then engaged in a lengthy shore bombardment that proved highly destructive to the civilian areas near the port. The U.S. sub chasers shifted to a screening role to protect the bombardment group from the two Austro-Hungarian U-boats that had slipped out of the port. Sub chaser No. 129 (SC-129) sighted the U-29 (or U-31) and SC-215 attacked with guns while SC-128 dropped depth-charges and claimed to have sunk the sub, which was actually damaged but got away. SC-129 then sighted and depth-charged another U-boat, which also damaged but not sunk. The shock of the depth charges crippled SC-129’s own engines, the most serious damage suffered by the U.S. boats that day. U-31 succeeded in putting a torpedo into the British light cruiser HMS Weymouth, which blew off a large part of her stern, but did not sink her. Another British destroyer was also hit by a torpedo, but not sunk. At one point during the battle, SC-130 headed off a column of Allied destroyers that was about to blunder into a minefield by shooting into the water ahead of the destroyers. An Austro-Hungarian steamer trapped in the harbor was the only ship on either side to be sunk during the battle, which one American submarine chaser skipper likened to “hitting a fly with a hammer.”

The American press, however, sensationalized the battle, hyping it as the “suicide mission” of the U.S. sub chasers, which wasn’t exactly the case. However, as the first surface engagement for the U.S. Navy since the Spanish-American War, the mostly very junior and inexperienced crews of the sub chasers acquitted themselves well. Captain Nelson was awarded the Navy Distinguished Service Medal and a variety of foreign awards, and would later be promoted to rear admiral.

The United States built 441 SC-1–class submarine chasers between 1917 and 1919 in response to direction from Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1916 to have the boats designed, so that if war came, they could be built en masse in civilian shipyards. The Navy deployed 121 SC boats to the European Theater, and their trans-Atlantic crossings were in many cases epic tales of survival in high seas and foul weather. Eventually, 36 SC boats would operate from “Base 25” in “American Bay” on the Greek island of Corfu, supported by the tender USS Leonidas (AD-7)—named after King Leonidas of 300 Spartans/Battle of Thermopylae fame—where they participated in the Strait of Otranto patrol. The 110-feet-long, gasoline-powered boats were generally armed with a 3-inch deck gun, machine guns, and depth-charge projectors, and had rudimentary hydro-acoustic listening devices—“K-tubes” and “MB-tubes”—and perhaps most importantly, radio-telephones that enabled them to operate efficiently as a coordinated group. Although there are no confirmed cases of a submarine chaser actually sinking a submarine during World War I, their sheer numbers and ubiquity no doubt disrupted many attempted submarine attacks.

(Source: America’s Sailors in the Great War: Sea, Skies, and Submarines by Lisle A. Rose, a very readable, concise, and well-researched treatment of the U.S. Navy’s contribution during World War I.)

(Back to H-Gram 021 summary)