H-057-2: I-400 and Operation Cherry Blossoms at Night: Japanese Plan for Biological Warfare – September 1945

H-057.2

Samuel J. Cox, Director, Naval History and Heritage Command

January 2021

Operation Cherry Blossoms at Night was a Japanese plan to wage biological warfare against cities in Southern California, in retaliation for the U.S. firebombing of Japanese cities, which killed hundreds of thousands of Japanese civilians. The Japanese plan called for using aircraft launched from I-400-class submarines to drop “bombs” containing millions of plague-infested fleas. The planned date for execution was 22 September 1945, however Japan announced intent to surrender on 15 August, which was formalized on 2 September 1945, forestalling the operation.

The plan was the inspiration of Surgeon General Shiro Ishii, the Director of Unit 731, the biological warfare unit of the Imperial Japanese Army, located in Harbin, Manchukuo (Japanese occupied Manchuria). Unit 731 conducted research on chemical and biological warfare agents, using live humans (including some Allied prisoners of war, including unconfirmed reports of U.S. POW survivors of the Bataan Death March) as test subjects. These included tests with bubonic plaque, anthrax, cholera, small pox, and botulism. The Japanese dropped bombs filled with biological agents on Chinese military and civilian targets. Although accurate numbers are hard to come by, more recent studies suggest the number of Chinese killed by Japanese biological warfare may have been in excess of 500,000. Unit 731’s experiments constituted some of the most horrific atrocities of the war, yet Ishii was granted immunity from prosecution for war crimes in exchange for his cooperation in sharing knowledge with U.S. biological warfare defense programs.

Early in the war, the Japanese considered using biological weapons against the stubborn U.S. and Filipino defenders of the Bataan Peninsula, using bombs filled with plague-carrying fleas, but the U.S. troops finally surrendered before the plan might have been executed. Consideration was also given to using high-altitude balloons to carry biological agents across the Pacific to the U.S. (In fact, beginning on November 1944, coincident with the first B-29 bomber raids on Japan, the Japanese began launching an eventual total of over 9,300 hydrogen-filled “Fu-Go” (Fire Balloons), which carried mostly incendiary and some anti-personnel bombs on the jet stream, with the intent to start large forest fires on the U.S. West Coast. At least 300 balloons actually reached the U.S. (and probably many more) but without the intended effects and were responsible for only six deaths in the U.S., all in one incident. Although ineffective, these fire balloons were considered to be the first “intercontinental weapons,” and were the longest combat raids ever conducted until the 1982 Falklands War. Some reports claim the Japanese attempted to use biological weapons against the U.S. Marines on Iwo Jima, using gliders with biological agents, which would be towed to Iwo Jima and released. However, the gliders never made it to Unit 731 to receive their payload.

As the situation in Japan became increasingly desperate in 1945, Ishii devised the plan code-named Operation Cherry Blossoms at Night, which was finalized in late March 1945. The plan called for five new I-400-class submarines, each with three Aichi M6A Seiran float-planes, to cross the Pacific and launch the aircraft with plague/flea bombs on one-way missions to crash into U.S. West Coast cities, with San Diego as the first target. When first presented, the plan was vetoed by Chief of the Army General Staff Yoshijiro Umezu, partly because the Navy didn’t have five I-400 submarines yet. Although Umezu would ultimately be the one ordered by Emperor Hirohito to sign the instrument of surrender aboard the USS Missouri (BB-63) on 2 September, in the last months of the war he was in the die-hard “fight-to-the-last Japanese” camp, and developed a renewed interest in the plan in August 1945 with the possibility that more I-400s might be completed by the proposed September attack date. Although the number of submarines available to carry out the plan was questionable, it was probably technically feasible and might have been executed had the war not ended when it did.

The Japanese I-400-class submarines were the largest ever built until the U.S. and Soviet nuclear ballistic missile submarines in the 1960s. The I-400 was 400-feet long with a displacement of 6,600 tons (compared to U.S. WWII fleet-type submarines of 300-feet, 2,200 tons displacement (submerged)). With a crew of 144, the I-400 carried eight 21-inch torpedo tubes forward (none aft), a 5.5-inch deck gun, and three triple-mount 25mm antiaircraft guns. The I-400 had the range to reach any location in the world and return to Japan. I-400 had numerous technological advancements including anechoic coating, advanced air and surface search radars and radar warning receiver. It also had twin-cylinder pressure hulls (a concept later used for the Soviet Typhoon-class ballistic missile submarine in the 1980s). One I-400 (I-401) was equipped with a snorkel.

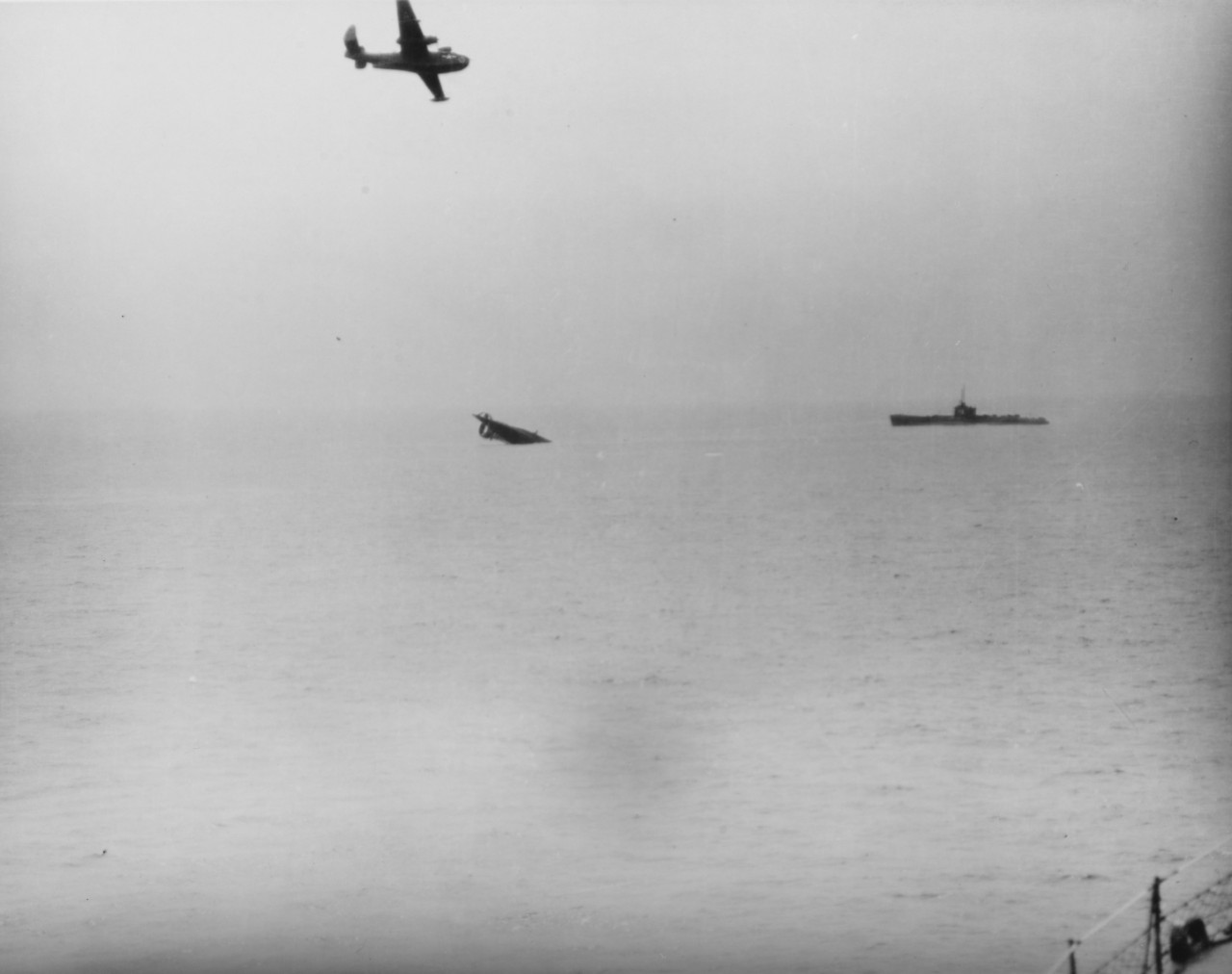

The I-400 class also had a hanger to carry three Seiran float-planes, which were launched by compressed air catapult with the submarine on the surface. It took 30 minutes to launch all three aircraft, although only 15 minutes if they were launched without floats, which meant the plane could not be recovered by the submarine. The sub also had a crane and could recover the aircraft, although this was a difficult process. The Aichi M6A Seiran was specially designed for the I-400. The existence of the Seiran was unknown to U.S. or Allied Intelligence until after the war ended. The Seiran was fast for a float-plane (295 knots) and had a maximum range of 641 NM with one Type-91 torpedo or an equivalent weight in bombs (1,874-pounds) and a crew of two. A total of 28 Seirans were built (only one survives, at Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center).

The I-400 class was conceived by Commander-in-Chief of the Combined Fleet, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, as a means to attack both the west and east coasts of the United States (Yamamoto even devised a plan to attack New York City and Washington D.C.). Before the I-400s, Japan had built about 40 submarines equipped with a hangar and a float-plane (a couple could carry two), intended to give their submarines a long range reconnaissance capability. A Yokosuka E14Y “Glen” float-plane from one such submarine, I-25, bombed Oregon with incendiary bombs twice in September 1942. (see H-gram 010/H-010-6). Others flew reconnaissance missions over Sydney, Australia, and other Allied locations. Nevertheless, Yamamoto wanted a submarine that could carry more aircraft, with more payload, at greater speed and range than the Glen.

Initially, the building plan called for 18 I-400s and construction commenced on 18 January 1943. After Yamamoto was shot down and killed the program was scaled back to nine, then five. By February 1944, four more I-400s were under construction, but only three of the five would be completed by the end of the war, and one of those (I-402) was completed as a submarine tanker. Only I-400 and I-401 entered service.

I-400 was commissioned on 30 December 1944 and I-401 on 8 January 1945. I-402 was completed on 24 July 1945 as a tanker, not as an aircraft submarine. I-403 was canceled in October 1943. I-404 was about 95 percent complete when work was stopped in June 1945, and she was subsequently heavily damaged in an air raid on 28 July 1945 and scuttled. Construction was also stopped on I-405 and she was scrapped. All other I-400s were canceled before construction was underway.

In 1944, the Japanese began devising a plan to attack the locks of the Panama Canal using I-400 and I-401 along with the older float-plane submarines, I-13 and I-14, which were specially retrofitted to carry two Seirans each, to provide an attack force of ten aircraft. The Seirans were to launch without floats off Ecuador and attack the canal from the Caribbean side; they would then return to the submarines and ditch alongside for aircrew recovery. In April 1945, the plan was changed to be a kamikaze suicide attack by the Seirans, although the aircrews were not informed of this change of plan. By 5 June, all four submarines had arrived at a Japanese bay (Nanao Wan, on the Sea of Japan side) which had a full-scale wooden mock-up of the Gatun Locks for target practice. By 20 June 1945 the operation was ready to proceed.

However, when Okinawa fell in June 1945, the Japanese naval general staff decided that the Panama Canal operation would have no impact on the course of the war. Instead, the Japanese became aware of the concentration of U.S. carriers (15 of them) at Ulithi Atoll in preparation for commencing attacks against the Japanese home islands. The Japanese devised a two-phase attack plan. In the first phase (Hikari), the submarines I-13 and I-14 were to transport four disassembled C6N Saiun “Myrt” high-speed reconnaissance aircraft to Truk Atoll (which although bypassed, was still a Japanese stronghold). The planes were to be re-assembled and used to conduct reconnaissance of Ulithi to confirm the presence of U.S. carriers. I-13 and I-14 would then go to Hong Kong and load two Seiran float planes each and then head to Singapore for further operations. However, I-13 never reached Truk as she was damaged by radar-equipped Avenger torpedo-bombers from escort carrier Anzio (CVE-57) and then sunk by depth charges from destroyer-escort Lawrence C. Taylor (DE-415) on 16 July 1945.

In the meantime, the plan called for I-400 and I-401 to conduct the second phase (Arashi) attack on Ulithi where they would rendezvous on 14/15 August 1945 and on 17 August launch their six Seians in kamikaze attacks on U.S. carriers at Ulithi. Each Seiran was to carry one 1,800-pound bomb bolted to the fuselage. Prior to leaving Japan, the Seirans were painted silver with U.S. white star markings, which actually offended the pilots, who considered it a dishonor to the Imperial Japanese Navy.

The Japanese surrender on 15 August put a stop to the Ulithi (and Cherry Blossoms at Night) operations. On 22 August, the Japanese submarines received orders to destroy their sensitive equipment. I-400 and I-401 fired off all their torpedoes and catapulted the float-planes without unfolding their wings, sending all to the bottom.

At the end of the war, the U.S. Navy boarded and recovered over 24 surviving Japanese submarines, including the three I-400s, which were all taken to Sasebo. The Soviets expressed an intent to inspect the submarines under the Japanese surrender agreement. In order to keep the Soviets from gaining access to the Japanese submarine technology, the U.S. Navy sailed the I-400, I-401, I-201, I-203, and I-14 to Pearl Harbor in October 1945. (I-201 and I-203 were advanced high-speed submarines, capable of 19 knots underwater, i.e., faster underwater than on the surface; only some advanced German submarines were as fast).

On 1 April 1946, all Japanese submarines still in Japan capable of sailing on their own power, including I-402, manned by skeleton Japanese crews, were taken to sea at a spot designated “Point Deep Six” and scuttled with demolition charges and gunfire from destroyer Everett F. Larson (DD-830) and submarine tender Nereus (AS-17) in “Operation Road’s End.” On 5 April, four disabled Japanese submarines were towed to sea and scuttled in “Operation Dead Duck.” Elsewhere in the Pacific other surrendered Japanese submarines as well as former German U-boats and Italian submarines that had ended up in the Pacific were also scuttled. None were turned over to the Soviets.

Following a period of test and evaluation in Hawaiian waters, the I-400, I-401, I-201, I-203, and I-14 were all scuttled at deliberately unrecorded locations. I-203 was torpedoed by Caiman (SS-323) on 21 May 46, I-201 by Queenfish (SS-393) on 23 May, I-14 by Bugara (SS-331) on 28 May, I-401 by Cabezon (SS-334) on 31 May, and I-400 by Trumpetfish (SS-425) on 4 June 1946.

The wreckage of I-401 was located by the Hawaii Undersea Research Laboratory deep-sea submarine Pisces at a depth of 2,300 feet southwest of Oahu in March 2005. I-14 and I-201 were found in February 2009 and I-400 in August 2013. As the submarines are actually U.S. Navy property, NHHC granted a permit to the Japanese television network NHK to do a documentary that included bringing up I-400s bell, which will be displayed at the USS Bowfin submarine museum in Pearl Harbor. The 24 Japanese submarines scuttled of Japan were located in 2015 by sonar.

Whether Operation Cherry Blossoms at Night could have been executed is debatable. The technology existed to conduct the attack. Although the Japanese Army was led to believe more I-400s would be finished by September 1945, that is doubtful given the acute shortage of materials (caused in large part by U.S. submarines sinking so many Japanese cargo ships). It’s remotely possible that I-402’s conversion to a tanker could have been stopped, but the bomb damage to I-404 would have prevented her being ready. In theory, the Japanese could have substituted I-13 (before she was sunk) and I-14 for two I-400s, and along with I-400 and I-401 could have launched a ten-plane biological warfare strike on Southern California. However, another thing working against the Japanese was the advanced proficiency of U.S. “Ultra” codebreaking and radio intelligence. By 1945, few Japanese submarines left port without U.S. Naval Intelligence knowing, along with the submarine’s anticipated general operating area. Pinpointing the Japanese submarines as they crossed the vast Pacific would have been challenging, but such a movement by Japanese subs would have provoked a massive U.S. response similar to that against German U-boats approaching the U.S. East Coast in the last month of the war.

How effective the “flea bombs” would have been is also debatable. Japanese biological weapons could inflict major casualties in the environment in China, but the same would not necessarily be true in the United States, with better sanitization and medical capability and much less population density (at the time). Nevertheless, as a weapon of terror, biological weapons certainly could have had a profound psychological effect, and the Japanese could have claimed a big propaganda victory, not that it would have done them much good given the force that was being arrayed against them for Operation Downfall, the planned invasion of Japan. Japanese use of biological weapons against the U.S. would have been considered reprehensible, but would have been yet another in a long list of war crimes committed by Imperial Japanese forces. The Japanese could also have just pointed to the ashes of their incinerated cities with massive civilian deaths and asked, “Why are fleas worse?” The U.S. use of the two atomic bombs made the whole discussion moot.

(Sources include: Operation Storm: Japan’s Top Secret Submarines and Its Plan to Change the Course of World War II, by John Geoghegan: Crown Publishing, 2013. Japan’s Infamous Unit 731, by Han Gold: Tuttle Publishing, 2011. “Japan’s Deadliest Weapons” by Norman Polmar in Naval History magazine, October 2020. Combinedfleet.com for Japanese submarine data and tracking).