H-Gram 062: "Battles That You've Never Heard Of," Part 1

11 June 2021

Download a PDF of H-Gram 062 (3.6 MB).

Overview

This H-gram covers “Battles You’ve Never Heard Of”: Nuku Hiva (1813), Negro Fort (1816), Quallah Battoo (1832), Muckie (1839), Drummond’s Island (1841), Ty-ho Bay (1855), and the Water Witch Affair (1855).

The Battle of Nuku Hiva, Marquesas Islands, Polynesia, 1813

In November 1813, in what was probably the largest amphibious assault in the Pacific in the 19th century, Captain David Porter of the frigate USS Essex, hit the beach on Nuku Hiva with 36 Sailors and Marines (and a wheeled cannon), and 200 war canoes with 5,000 Te I’i and Happah tribal warriors. Having quickly grasped the implications of shipboard cannons, the Tai Pi warriors wisely chose not to defend at the beach. However, as Porter and his allied warriors (from the other side of Nuku Hiva) advanced toward a fortification held by 4,000 Tai Pi, ambushes and skirmishes increased, and Porter’s native allies began to melt away. Porter’s Marines used muskets to pick off Tai Pi warriors on the ramparts until they ran low on ammunition, but thick vegetation around the fort made the cannon ineffective. Short on ammunition and left to fend for themselves, Porter’s force withdrew back to the beach. Displaying a healthy respect for musket fire, the Tai Pi did not seriously challenge Porter’s retreat to the ship and the Americans got off lightly with only one dead and two seriously wounded.

Despite the defeat, Porter would subsequently launch a surprise overland attack and burn the Tai Pi villages (for which the British would accuse him of excessive brutality). After the subsequent departure of Essex and most of the small flotilla of captured British whalers, the Nuku Hiva warriors would join together to drive the first U.S. naval base and colony in the Pacific (“Madisonville”) off the island by the end of March 1814.

The Battle of Negro Fort, Spanish Florida, 1816

On the morning of 27 July 1816, U.S. Navy Gunboat No. 154 fired the deadliest cannonball in U.S. history. After several ranging shots, No. 154 fired her first “hot shot” up over the bluff and the rampart; the heated ball rolled right into the powder magazine. The resulting massive blast could be heard in Pensacola, over 100 miles away. Over 270 Blacks and Native Americans in the fort were killed instantly and another 60 were wounded, many grievously; only three survived unharmed (two of whom were subsequently executed). The fort was manned by about 200 armed fugitive Black slaves and 30 Native Americans, and the rest were women and children—families of the escaped slaves. Many of the fugitive slaves had been recruited, armed, and trained by the British during the War of 1812 for a force known as the Colonial Marines.

The combined Army and Navy assault on the fort had been ordered by General Andrew Jackson at the behest of Southern slave-holding plantation owners, who could not abide that the fort was a magnet for escaped slaves and wanted this symbol of Black freedom crushed. That the fort was in Spanish territory and the occupants flew the Union Jack (considering themselves British subjects) troubled Jackson not at all, although the U.S. government retroactively approved his action on grounds of “national defense.” The destruction of the fort put an end to the largest concentration of armed free Blacks in North America and the subsequent flight of Black farmers from the surrounding area ended the largest community of free Blacks in North America (and Jackson would later destroy their subsequent refuge).

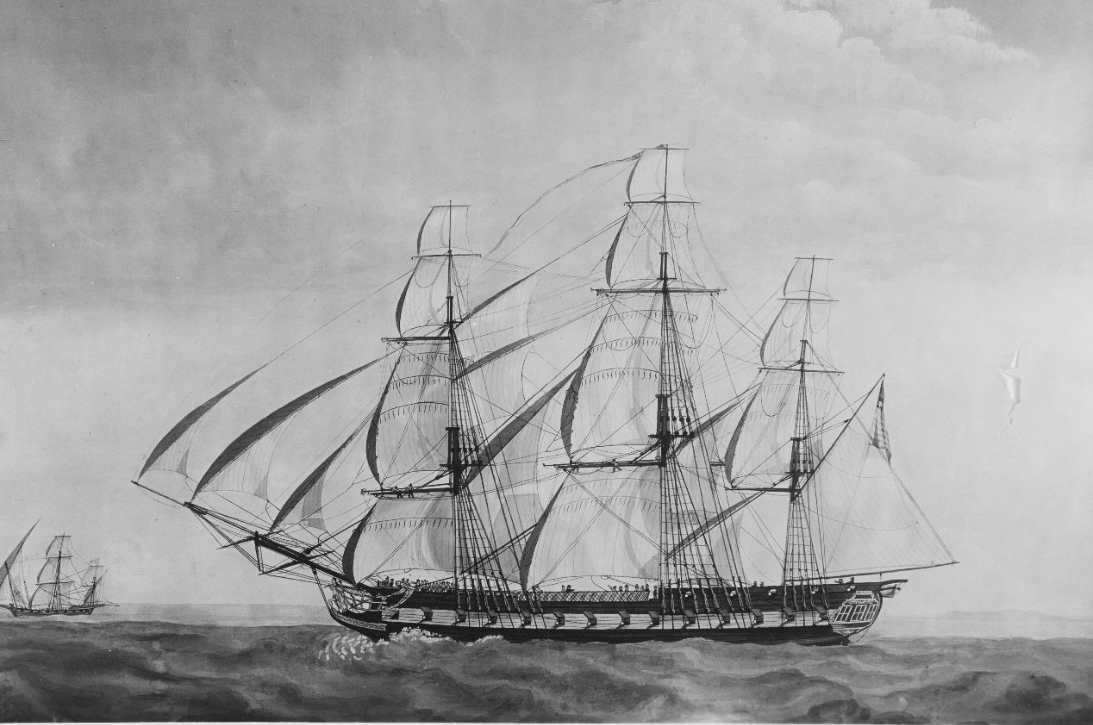

The Battle of Quallah Battoo, Sumatra, 1832

On 5 February 1832, the most powerful and technologically advanced frigate in the U.S. Navy, USS Potomac, arrived off the Malay settlement of Qualla Battoo on Sumatra disguised as a merchant ship flying the flag of Denmark. Under cover of darkness, a landing party of 282 Marines and armed Sailors attacked and captured four of five palace forts defending Qualla Battoo. Taken by surprise, the Malay warriors nevertheless fought fiercely, including suicide charges, and none surrendered, preferring to fight to the death (wives would take up their fallen husbands’ arms and were also killed). The Malays’ arms were no match for those of the landing force, and an estimated 150 Malays were killed in the forts. U.S. casualties were three dead and about 10 wounded. After withdrawing the landing force the next day, Potomoc pulled in close to the shore and fired several devastating broadsides into the fifth fort and town, by some accounts killing 300 more Malays.

Under the command of Commodore John Downes, the mission of Potomac was President Andrew Jackson’s answer to the plunder and murder of several crewman of the American-flag merchant ship Friendship off Quallah Ballou a year earlier. Downes was authorized to negotiate with a government, if he could find one, for restitution and punishment of guilty individuals. Failing that (he made at best a cursory attempt), his orders were to inflict such “chastisement” so as to ensure no further attacks would be made on U.S.-flag ships. It worked for six years, and the “First Sumatran Expedition” is one of the first actions by the United States that would come to be known as “gunboat diplomacy.”

The Battle of Muckie, Sumatra, 1839

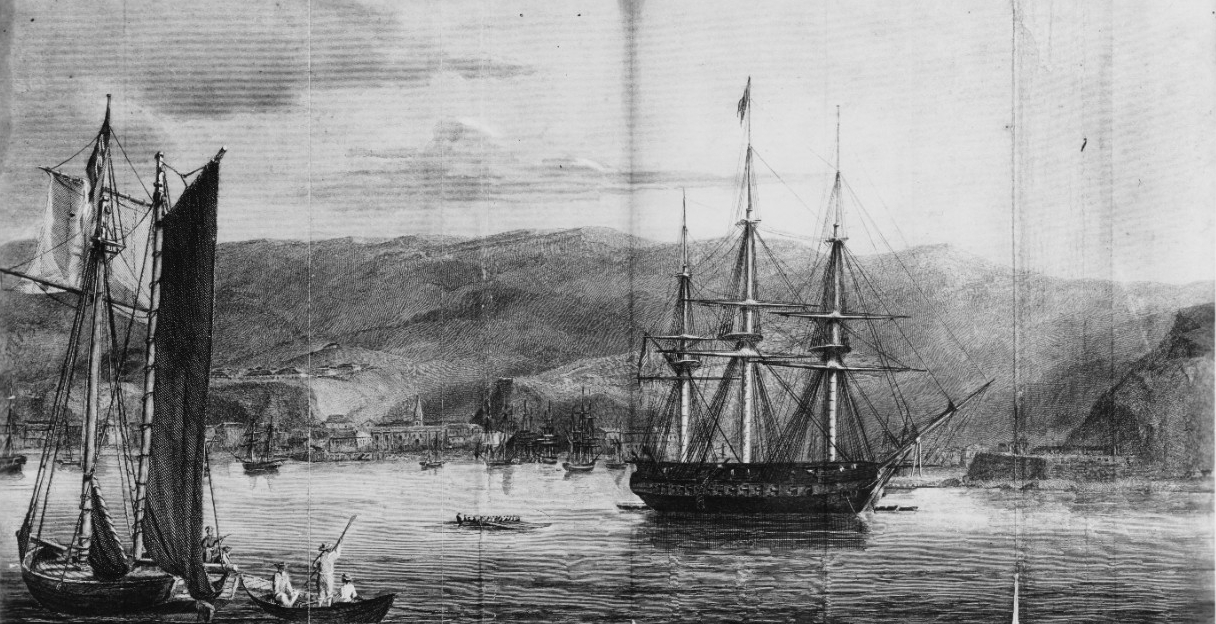

The hiatus in Malay piracy of U.S. merchant ships engaged in the pepper trade in Sumatra lasted only six years until the merchant vessel Eclipse was taken and her entire crew massacred in 1838. In 1831, it had taken a year before the first U.S. Navy ship had arrived to exact retribution. This time it only took 20 days from the time Commodore George C. Reade, commander of the East India Squadron, first learned of the massacre and the arrival off Quallah Battoo, Sumatra, by USS Columbia, the newest and most heavily armed frigate in the U.S. Navy, and the smaller battle-veteran frigate John Adams (history lesson: the importance of forward deployment of naval forces).

As a lieutenant, Reade had participated in the defeat of HMS Guerriere by USS Constitution and of HMS Macedonian by USS United States during the War of 1812. As commodore, he wasted no time, and after fair warning blasted the forts of Quallah Battoo. He then sailed his squadron a few miles down the coast to the settlement of Muckie. Under covering fire from the frigates, a 360-man landing party of Marines and armed Sailors went ashore. Unlike the Malay warriors who had fought to the death against the 1831 expedition, the Malays had fled, and the fort and town were deserted. The landing party proceeded to burn the town and fort, and spike the guns. No remnants of Eclipse were found. Malay casualties at Quallah Battoo and Muckie are unknown, but there were no further attacks on American shipping in the area. No U.S. Marines or sailors died in the operation, although 20 sailors had previously died of dysentery on the voyage to the East Indies.

The Battle of Drummond’s Island, Gilbert Islands, 1841

On 9 April 1841, over 100 years before the amphibious assaults on Japanese-held Tarawa and Makin atolls in the Gilbert Islands (now Kiribati), about 80 U.S. Marines and armed Sailors from the sloop-of-war USS Peacock and schooner USS Flying Fish engaged in a battle with almost 700 warriors on Drummond’s Island (now Tabiteuea). Precipitated by the disappearance of a U.S. Navy Sailor, the purpose of the landing was to burn down the village of Utiroa in retribution, as ordered by the commanding officer of Peacock, Lieutenant William L. Hudson. The warriors met the seven U.S. boats at the beach and initially drove the boats back before volley fire from the boats repulsed the warriors, spears, stones, and clubs proving no match for modern muskets. Twelve warriors were killed and many were wounded, and the Americans burned the village (home to over 1,000 natives). This was one of several violent confrontations—to include incidents at Fiji and Samoa—between Pacific Islanders and ships of the United States Exploring Expedition (U.S. Ex. Ex.) under the command of Lieutenant Charles Wilkes. The scientific and exploration achievements of U.S. Ex. Ex. were extraordinary, including the discovery of the continent of Antarctica. The three violent encounters were somewhat less than glorious.

The Battle of Ty-ho Bay, China, 1855

There was little love lost between the U.S. Navy and the British Royal Navy in the aftermath of the War of 1812. However, on occasion, the two navies found cause to cooperate, and suppressing piracy was something on which everyone could agree. On 4 August 1855, the steam vessel HMS Eaglet towed six boats with about 100 U.S. Marines and armed Sailors, and a roughly equal number of British Marines and Sailors, into the shallow water of Ty-ho Bay (on Lantau Island in present-day Hong Kong) to attack a Chinese pirate force of 14 cannon-armed large junks and 22 smaller junks with a total of about 1,500 pirates. The Sailors were from the paddle-wheel steam frigate USS Powhatan and screw steam sloop HMS Rattler, neither of which could enter the bay due to its shallow waters. Cannon fire from the pirate ships was heavy, but wildly inaccurate. Cannon and howitzer fire from the British and U.S. small boats was not (the U.S. boats were equipped with the new Dahlgren boat howitzers, considered the best boat guns of the day). Six pirate junks were sunk before the “Allied” boats grappled alongside.

When the Battle of Ty-ho Bay was over, all 14 of the large pirate junks were sunk or burned, along with six smaller pirate junks. About 500 pirates were killed, drowned, or wounded, and 1,000 captured; 16 small pirate junks escaped. The U.S. suffered five dead and six wounded, while the British suffered four dead and several wounded. The Battle of Ty-ho Bay would be the last major pitched battle between Chinese pirates and Western navies, and would be one of the very first “combined” operations by the U.S. and Royal Navies (although it wouldn’t be until World War I, with a few individual exceptions, when relations could accurately be characterized as “friendly.”)

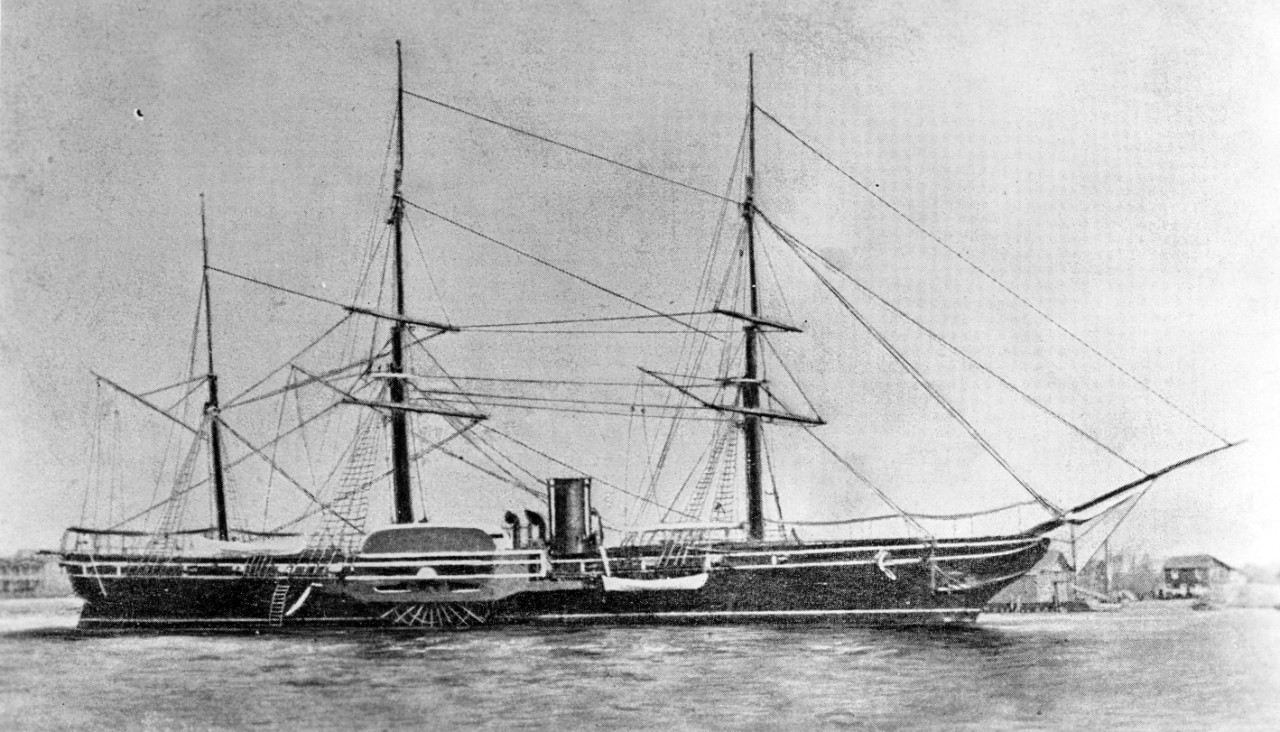

The Water Witch Affair, Paraguay, 1855

The largest U.S. Navy ship deployment prior to the Civil War was to—you guessed it—Paraguay (no, you didn’t!). On 1 February 1855, the U.S. Navy steam paddle-wheel gunboat Water Witch entered Paraguayan territorial waters on the Parana River despite a decree from the president of Paraguay forbidding warships of any nation to enter, and despite multiple warnings by small boat, hail, and warning shots from Paraguayan Fort Itapiru. Finally, the fort fired a live round that killed the helmsman of Water Witch. Water Witch returned fire, but the fort got the best of the engagement, hitting the U.S. vessel multiple times with accurate fire, although Water Witch made good her escape.

Over two years later and pretty much out of the blue, President James Buchanan decided that this affront to the U.S. flag required a punitive U.S. naval expedition to compel an apology from Paraguay and financial restitution for other grievances. The expedition, under the command of Commodore William Shubrick, included 12 ships (plus seven more charters), over 200 guns, and 2,500 men, and cost over three million dollars. It didn’t reach the Rio de la Plata until almost three years after the Water Witch incident. Woefully short on ammunition, coal, and just about everything else, the U.S. force was given completely unrealistic objectives. The deployment revealed just how far the readiness of the U.S. Navy had decreased since the end of the Mexican-American War. Fortunately, the Paraguayans did not call the Navy’s bluff and a face-saving diplomatic agreement was reached. Otherwise, this expedition might well have become one of the biggest fiascos in U.S. naval history.

For more on these battles, please see attachment H-061-1. As always, feel free to spread H-grams around so more people will know the valor of Sailors who did what their country asked, sometimes in a dubious cause, and gave their lives in faraway places in forgotten battles. Back issue H-grams may be found here.

P.S.: I don’t recommend the Secretary of the Navy name a ship after any of these battles.