H-046-2: Kikusui No. 5—"Chrysanthemums from Hell," 4 May 1945

Suicide Boat Attack, 3 May 1945

After sunset on 3 May, a Japanese army suicide boat of the “27th Suicide Boat Battalion” entered the fray in the waters off Okinawa. Although spotted by a minesweeper and illuminated by a searchlight, the one-man boat successfully rammed the attack cargo ship Carina (AK-74) and detonated the onboard explosives. Luckily, a landing craft moored alongside Carina absorbed much of the large explosion that flooded one hold and knocked out a boiler. The ship remained afloat with no crewmen killed and only six wounded. Inspection the next morning revealed significant cracks in the deck and the hull that the commanding officer assessed would cause the ship to break up in a moderate sea. Effective damage control not only saved the ship, but also the cargo, which could be offloaded before Carina received temporary repairs at Kerama Retto. She then sailed to the States, where she still was when the war ended.

Kikusui No. 5, 4 May

Sunrise on 4 May was clear with great visibility over Japanese airfields on Kyushu. This meant it was going to be a really bad day near Okinawa. Kikusui (“Floating Chrysanthemums”) No. 5 mass kamikaze attack included only about 125 aircraft (50 from the army and 75 from the navy). In terms of types of aircraft, the Japanese threw in everything but the kitchen sink. The army aircraft included Nates, Oscars, Tonys, Franks, and Nicks, the first four all single-engine fighters of various types. The navy’s contribution to Kikusui No. 5 included a large number of obsolete aircraft: older models of Zeke fighters and Val dive-bombers. There were also seven Betty twin-engine bombers, each carrying an Ohka rocket-assisted manned suicide flying bomb. The air attack also included float planes for the first time, including three Aichi E13A1 Jakes (the Japanese Navy’s standard battleship/cruiser-catapulted long-range reconnaissance aircraft) plus 15 early–1930s vintage Kawanishi E7K2 Alf wooden biplane seaplanes (obsolete and retired to second-line duty even before the start of the war).

Kikusui No. 5 began launching from airfields on Kyushu at 0500, led by a fighter sweep of 48 navy Zekes and 25 army Ki-84 Franks. Most of the Japanese fighters would be shot down by U.S. fighters, but they created enough of a distraction that enough of the kamikaze aircraft would get through to make 4 May 1945 the single most painful day for the U.S. Navy off Okinawa (although still more to come in the next weeks were almost as bad). Kikusui No. 5 would for the first time shake U.S. Navy resolve to continue to stand and fight in range of land-based air, losing the advantage that ship mobility provided.

The “mass” kamikaze raid is a bit of a misnomer in that the Japanese had learned to stagger the attacks in terms of time, altitude, speed, and course/direction. Some aircraft made solo flights. Most attacked in groups of 6–7 aircraft, as the Japanese learned that was the optimal size for at least a couple to get through the U.S. fighter combat air patrols (CAP). Although the kamikaze pilots were uniformly brave, many of them were barely trained, and their flying skills were generally much less than those of the suicide pilots in the Philippines campaign (particularly those at Lingayen Gulf). However, there were a lot more of them and they were now directly defending their homeland. Their recognition skills were also poor (recognition was a problem for even good pilots on both sides throughout the war). There was a strong tendency for the Japanese pilots to go after the first ships they saw, which was usually the destroyers on Radar Picket Station No 1 to the north of Okinawa, although RP2, 3, 14, and 15 were kamikaze bait as well.

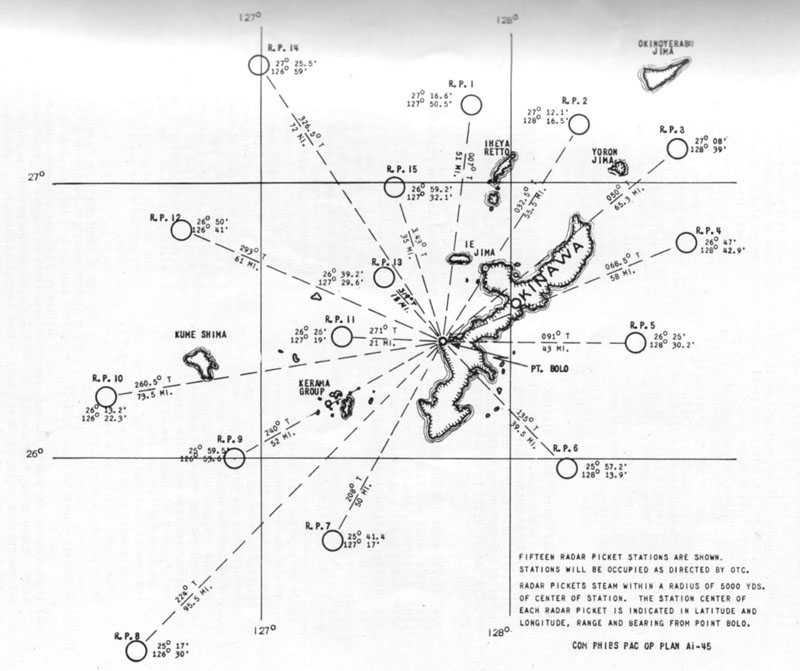

There were 16 radar picket stations providing 360-degree coverage around Okinawa, from RP1 about 50 nautical miles almost due north, clockwise around the island at staggered distances to RP 14 and 15 to the north-northwest, with RP14 the farthest out at 75 nautical miles. Most of the RPs were stationed to optimize coverage from the sectors from west to northeast (the direction of attack from Japanese airfields on Kyushu). RP16 didn’t fit the numbering pattern and was about 50 nautical miles to the northwest between RP11 and RP12. RP8, about 100 nautical miles to the southwest, provided the farthest-out coverage of the axis of attack from Formosa.

Chart showing radar picket positions off Okinawa, May 1945. Radar pickets steamed within a radius of 5,000 yards of the center of their station. The station center of each radar picket is indicated in latitude and longitude, and range and bearing from point "Bolo" (Naha, Okinawa). Excerpted from "Battle Experience: Radar Pickets and Methods of Combating Suicide Attacks Off Okinawa, March–May 1945," COMINCH Headquarters, Washington, DC, 20 July 1945.

Loss of Morrison (DD-560) and LSM(R)-194 on Radar Picket Station No. 1

Due to intelligence reports and the weather forecasts, all U.S. ships around Okinawa were expecting a major kamikaze attack on the morning of 4 May. The Japanese would not disappoint and, as usual, Radar Picket Station No. 1 would be a really bad place to be. The destroyers Morrison (DD-560) and Ingraham (DD-694) had drawn the figurative short straw and were at RP1, supported by LSM(R)-194 and three large support landing craft, LCS(L)-21, LCS(L)-23, and LCS(L)-31. In the black humor typical of Sailors, the assisting amphibious craft had become known as “pallbearers.”

Morrison (DD-560) was commanded by Commander James R. Hansen, and had been on RP1 since 1 April. She had a fighter-direction team embarked to control combat air patrol (CAP) fighters. Hansen was combat experienced and already had a Silver Star from a tour as combat information center (CIC) evaluator aboard destroyer Chevalier (DD-451) when she was lost in the vicious night Battle of Vella LaVella on 6 October 1943 (see H-Gram 022). Morrison was a Fletcher-class destroyer (five single 5-inch/38-caliber guns) and, on 31 March, had sunk the infamous Japanese submarine I-8 after depth-charging her to the surface and putting her under in an exchange of gunfire off Okinawa (see H-Gram 045). Morrison had also previously rescued 400 survivors of the light carrier Princeton (CVL-23) on 24 October 1944 and had suffered damage when her mast and forward stack had gotten caught in Princeton’s uptakes.

Ingraham was a relatively new Allen M. Sumner–class destroyer (three twin 5-inch/38-caliber guns) commissioned in March 1944, and was the third destroyer named after Captain Duncan Ingraham, who had served as chief of the Confederate ordnance bureau in the Civil War. The second Ingraham (DD-444) had been lost in a tragic collision in the fog off Nova Scotia on 22 August 1942, when she was accidentally rammed and sunk by the oiler Chemung (AO-30) while Ingraham was going to the aid of destroyer Buck (DD-420), which had collided with a merchant ship. Ingraham’s depth charges went off as she was sinking. Only 11 of her crew survived and 218 were lost, one of the worst non-combat losses in the Navy’s history. The third Ingraham’s skipper, Commander John Frank Harper, Jr., had been awarded a Silver Star for his actions in command of the destroyer at the Battle of Lingayen Gulf in January 1945. Also embarked on Ingraham was Commander John Crawford Zahm, the commander of Destroyer Division 120, who was the officer in tactical command at RP1 on 4 May. He already had three Silver Stars from the D-Day landings at Normandy, and from the landings at Ormoc Bay and Lingayen Gulf in the Philippines.

LSM(R)-194 was under the command of Lieutenant (j.g.) Allen M. Hirshberg, USNR. The vessel was one of a class of 12 LSMs that had been extensively modified to deliver a massive rocket barrage in support of amphibious landings. In April, the commander of LSM forces (Flotilla 9) had recommended against using the LSM(R) on radar picket duty, as the ships were ill-suited for anti-aircraft defense (no radar), because of their comparative scarcity and specialized nature (only 12 of them), and, with the large number of rockets on board, had a vulnerability similar to ammunition ships. In an example of failure to quickly adapt, his recommendations were not implemented, and three of the vessels—LSM(R)-195, 194, and 190—would be lost in quick succession on 3 and 4 May 1945 before it was recognized that using them in this role was a bad idea.

Radars on Morrison and Ingraham began picking up large inbound raids at about 0715. The fighter-direction team on Morrison vectored shore-based Marine F4U Corsair fighters of VMF-224 and 12 Hellcats of VF-9 off Yorktown (CV-10) under its control to intercept. Other aircraft from Yorktown engaged as well (about 32 U.S. aircraft were in the area of RP1). Reports from numerous ships described a massive air battle seen on radar north of Okinawa as numerous U.S. fighters engaged the Japanese. Many Japanese aircraft were shot down, but the enemy’s fighter sweep and dispersed tactics enabled a significant number to get through. Morrison’s fighters handled the first three raids (about 25 aircraft) heading for RP1, but a Val dive-bomber finally broke through. Although pursued by four Corsairs and hit repeatedly by fire from the fighters and Morrison’s gunners, the Val kept boring in from the bow and grazed the top of Morrison’s No. 2 5-inch gun mount and the bridge before crashing ten yards astern in the ship’s wake.

A few minutes later, another Val dive-bomber made it through the fighter gauntlet and, with Corsairs on its tail, was shot down 2,500 yards short of Morrison. Although additional combat air patrol fighters arrived in the area (now up to about 48), a Japanese Zeke fighter, also pursued by Corsairs, got close enough to drop a bomb that hit 50 yards from Morrison’s port beam while the Zeke impacted the water 50 yards on the starboard beam, neither causing significant damage. Then, another Val with fighters on its tail aimed for Morrison’s bridge, disintegrating at the last moment, with most of the plane impacting the water 25 yards away. However, parts of the plane’s wing and landing gear hit the bridge. At 0825, a fifth Japanese plane grazed the aft stack before crashing in the water. At this point, Morrison’s luck had run out.

Two Zeke fighters made near-vertical dives in quick succession (although these are described as navy Zekes in almost every account, Japanese records indicate these are probably Japanese army Ki-84 Frank fighters). The first Zeke clipped the after stack before penetrating into the ship at the foot of the forward stack, the bomb detonating in the forward fire room and causing the No. 1 boiler to explode. This crash caused heavy casualties on the bridge, in the radio and plotting rooms, and in the forward fireroom, as well as knocking out most of the electrical power equipment. The second Zeke hit close to the No. 3 5-inch gun mount, crashed through the main deck, and penetrated into the after engine room. It blew a large hole in the ship’s hull plating and opened the aft engine room to a massive influx of water. Morrison was in big trouble, but her crew still had a decent chance to save her. Then, the Alfs attacked.

Accounts described the bi-wing floatplane Alfs coming in like a flight of pelicans in two groups of seven, low and slow, with the assessment that the leader of each group was a skilled pilot, but the rest barely knew how to fly. Fighters swarmed the Alfs, which proved surprisingly hard to bring down despite the fact that almost none of them maneuvered at all to avoid attack. Nevertheless, almost all of the Alfs went down, but the survivors kept coming. It turned out the 5-inch variable-time (VT) radar-proximity fuze shells didn’t work against the wooden Alfs.

One of the Alfs approached from Morrison’s stern and was hit repeatedly by 20-mm fire that passed clean through. The Alf shed bits of fabric on the aft 20-mm gunners before it crashed into the 40-mm mount on the aft deckhouse and the No. 3 5-inch gun just forward of that. Powder in the upper handling room ignited, blowing the 5-inch gun off its foundation and causing additional damage to an already gravely weakened part of the ship. Although old and slow, the Alfs were each carrying a big 1,000-pound bomb.

Accounts differ as to whether Morrison was hit by two or three Alfs, but no one who saw it could forget the last one. Approaching Morrison from astern with Corsairs closing in for the kill, the Alf pilot set his floatplane down in the water, causing the fighters to overshoot. Taxiing in the wake of Morrison, under fire, the Alf took off again and then crashed into Morrison’s No. 4 5-inch gun turret, setting off a massive powder explosion that doomed the ship. Uncontrollable flooding in the aft part of the ship and rapidly increasing starboard list caused Commander Hansen to give the abandon ship order immediately, but most of the ship’s internal communications had been knocked out and most of the men below decks didn’t get the order or couldn’t get out in time. At 0840, the ship sank by the stern, bow pointing skyward, in less then ten minutes from the last hit, with very heavy casualties. Morrison suffered 153 men killed or missing, and 108 of her 179 survivors were wounded—six of them subsequently died. (There are major discrepancies in various accounts regarding the order of hits and types of aircraft, and in such cases I tend to hew toward Morison).

Ingraham came under concentrated kamikaze attack at the same time as Morrison. Ingraham’s after-action report was particularly detailed regarding the Japanese tactics, noting that the first attacks were by very fast modern aircraft in singles or small groups from widely separated sectors, building up in numbers until the CAP fighters were overloaded. This was followed by the Alf biplanes, which were almost all shot down, and then by older land-based aircraft. The Japanese planes approached in loose formation (probably because many had been shot down by fighters) and split up, attempting to conduct an ad hoc simultaneous attack from widely different directions with varying attack profiles.

Ingraham was credited with shooting down six Japanese aircraft and assisting in downing three others. The destroyer shot down the first four (or five) kamikaze that attacked her (two were near misses) before a fifth (or sixth) crashed her just above the waterline on the port side near No. 2 5-inch gun mount. The Zeke’s bomb exploded in the generator room and the combined effect led to flooding in the forward fireroom and knocked out electrical power to almost all the ship’s guns. Down 14 feet at the bow and vulnerable, she was spared from further attack, but suffered 15 dead and 37 wounded.

While maneuvering to aid the damaged Ingraham and survivors of Morrison, LSM(R)-194, which has put up a gallant fight to that point, was hit in the stern at 0850 by a damaged Tony fighter that had been hit by fire from LCS(L)-21 (Japanese records indicate no Ki-61 Tonys participated). As predicted, the combination of the kamikaze and the vessel’s own rockets was deadly. LSM(R)-194 sank quickly with 13 crewmen missing (later declared dead) and 23 wounded. A large explosion occurred just as the vessel went down, damaging LCS(L)-21 which was coming to LSM(R)-194’s aid.

Despite her damage, LCS(L)-21 picked up 187 survivors of Morrison and Ingraham (who had been blown overboard) and another 49 survivors of LSM(R)-194, with LCS(L)-31 picking up the rest. Counting her own crew, LCS(L)-21 had over 300 men aboard. In addition, the vessel had shot down three planes (four, counting the one that hit LSM[])-194 instead of the water). LCS(L)-23 shot down four Japanese planes. LCS(L)-31 was nearly hit by two kamikaze: one carried away the ensign before crashing in the water and the wings of the second hit the conning tower and forward gun tub as the fuselage passed between them and out the other side. A third kamikaze hit the main deck aft, but even though badly damaged, LCS(L)-31 shot down two more Japanese aircraft, suffering eight dead and 11 wounded. Most of these aircraft were identified as Val dive- bombers, but were most likely older Japanese army Nate fighters with fixed landing gea), which would explain why so many of them were expending themselves against such relatively small targets. In a number of cases, Japanese planes also strafed survivors in the water, and others crippled by U.S. fighters attempted to crash into clumps of floating survivors. Nevertheless, most of the survivors were rescued within three hours.

Morrison, Ingraham, and LSM(R)-194 were each awarded a Navy Unit Commendation, with that for Morrison noting her “firing resolutely until she went down.” Captain (and future Vice Admiral) Frederick Moosbrugger, overall commander of the radar picket destroyers, lamented in his report that the loss of Morrison was “all the more regretted in view of the gallant fight to the finish.” Fleet Admiral Nimitz readily concurred with that assessment. What may be even more lamentable is that in 1957, the U.S. Navy donated the wreck of Morrison (and 26 other ships) to the Government of the Ryukyu Islands for scrap, so the last resting place of the Sailors who so valiantly served on her is gone. Ingraham returned to the United States for repairs, which were not completed before the war ended. She, at least, went on to distinguished service in the Korean War, Cold War, Vietnam, and in the Greek navy before being sunk as a target in 2001.

Commander John C. Zahm, Commander James R. Hansen, Commander John F. Harper, Jr., and Lieutenant (j.g.) Allen M. Hirshberg, were each awarded the Navy Cross with the following citations:

The President of the United States takes pleasure in presenting the Navy Cross to Captain (then Commander) John Crawford Zahm, United States Navy, for extraordinary heroism while serving as Officer in Tactical Command of a Radar Picket Station Unit in the vicinity of Okinawa on 4 May 1945. During an overwhelming and savage Japanese suicide attack he fought his unit with such skill and vigilance that more than forty-two enemy planes were destroyed by ship’s gunfire and the combat air patrol. His inspiring leadership and devotion to duty in the face of savage enemy attack were in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.

***

The President of the United States takes pleasure in presenting the Navy Cross to Commander James Richard Hansen, United States Navy, for extraordinary heroism and distinguished service in the line of his profession as Commanding Officer of Destroyer USS MORRISON (DD-560), in action against enemy Japanese forces in the vicinity of Okinawa on 4 May 1945. While on radar picket duty in advance of the main body of our fleet, accompanied by another destroyer and four smaller vessels, Commander Hansen gallantly fought his ship during a two-hour battle with more than forty enemy planes. Under the violent bombing, strafing and suicide attacks of the hostile aircraft, he carried our radical defensive maneuvers and directed his gun batteries in maintaining a tremendous volume of anti-aircraft fire. After the ship was hit by four suicide planes and fatally damaged, Commander Hansen inspired his officers and men to continue the fight and make every effort to save their sinking ship. His indomitable fighting spirit and unwavering devotion to duty were in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.

***

The President of the United States takes pleasure in presenting the Navy Cross to Commander John Frank Harper, Jr., United States Navy, for extraordinary heroism and distinguished service in the line of his profession as Commanding Officer of the Destroyer USS INGRAHAM (DD-694), in action against enemy Japanese forces during an air-sea battle off Okinawa on 4 May 1945. With the ships of his formation subject to continuous bombing, strafing and suicide attacks by more than fory enemy planes, Commander Harper gallantly met the savage assaults and fought his ship brilliantly, maintaining devastating anti-aircraft for to shoot down five of the hostile aircraft. When a sixth plane crashed on boar and caused serious flooding during a coordinated attack, he personally surveyed the damage and directed the control and, by his unfaltering leadership, aided materially in saving his ship and in keeping her guns firing until the last of the attackers had been destroyed. His courage and determination throughout were in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.

***

The President of the United States takes pleasure in presenting the Navy Cross to Lieutenant Allen Myers Hirshberg, United States Naval Reserve, for extraordinary heroism and distinguished service in the line of his profession as Commanding Officer of the USS LANDING SHIP MEDIUM (Rocket) ONE HUNDRED NINETY-FOUR (LSM(R)-194), a close-in fire support ship, in action against enemy Japanese forces during the assault on Okinawa, Ryukyu Islands, on 4 May 1945. After a bomb-laden suicide plane crashed into his ship, Lieutenant Hirshberg directed from the conn the entire damage control and, displaying exceptional courage when it became necessary to abandon ship, remained to supervise the continuous fire of his anti-aircraft batteries against further enemy air attacks. His outstanding courage and his inspiring leadership of officers and men under his command reflect the highest credit upon Lieutenant Hirshberg and the United States Naval Service.

Loss of Luce (DD-522) and LSM(R)-190 on Radar Picket Station No. 12

As the battle at Radar Picket Station No. 1 was raging, other Japanese aircraft were approaching RP12 from the west-northwest, patrolled by destroyer Luce (DD-522). Known as the “Lucky Luce” by her crew, this would not be her lucky day. Luce was commanded by Commander Jacob Waterhouse. As RP12 had not seen near as many kamikaze attacks as the stations to the north, Luce was on station accompanied only by four smaller amphibious vessels, LSM(R)-190, commanded by Lieutenant Richard H. Saunders, as well as LCS(L)-81, 84 and 118.

At 0740, combat air patrol fighters intercepted Japanese aircraft approaching Luce’s stations and shot down a number of them. At 0808, two kamikaze broke through the fighter gauntlet and attacked the destroyer, splitting up to make runs from opposite directions. Luce opened fire on the aircraft at 8,000 yards. Despite taking repeated hits, both aircraft refused to go down. The first kamikaze nearly hit the bridge and crashed a few feet to starboard, but the bomb explosion caused a brief power failure throughout the ship, knocking out all the radars. Guns trained manually on the second kamikaze coming in from the port quarter, but only a few had a brief opportunity to fire before the plane crashed into the port side below the No. 3 5-inch gun mount. It inflicted severe damage to the after engine room, flooding that space and others aft, and jamming the rudder hard over.

Luce quickly took on a heavy list and was going down by the stern with uncontrollable flooding. At 0814, Commander Waterhouse gave the abandon ship order, which was followed a minute later by a massive explosion as the ship went under. Almost no one below decks made it out, and additional men were killed when Luce’s depth charges went off under water; 149 crewmen were lost with the ship and another 94 were wounded, including the badly injured Waterhouse. This was an example in which whether a ship survived or sank had a lot to do with where the kamikaze hit, and sometimes no amount of valor or skill could save the ship. Waterhouse would be awarded a Silver Star for his actions in the few minutes he had to fight and try to save his ship.

At the same time Luce was coming under attack, an aircraft identified as a “Dinah” overflew LSM(R)-190 and dropped a bomb that missed. (The Ki-46 Dina was a high-speed twin-engine army reconnaissance aircraft that was so fast few were ever shot down. There were a small number configured for ground attack.) When the Dinah was hit by anti-aircraft fire, it flipped over and commenced a dive on LSM(R)-190, crashing into the 5-inch gun mount, setting it on fire, and severely wounding Lieutenant Saunders, the commanding officer, who was in and out of consciousness for the rest of the fight, and killing the gunnery officer. A radioman took over the conn until relieved by the vessel’s communications officer, Ensign Lyle Tennis, who continued the fight.

Tennis ordered that the sprinkler system in the rocket magazine and aft rocket assembly room be turned on, but water pressure was minimal due to ruptured fire mains, and the fire from the 5-inch gun spread to the upper handling room. Nevertheless, the ship kept shooting as a second kamikaze came in low on the port beam and crashed into the upper level of the engine room, which soon had to be abandoned due to choking smoke. Even with the engine room turned into a blast furnace, LSM(R)-190 continued at flank speed with radical maneuvers that caused another pass at masthead height by a high-speed twin-engine Japanese fighter (probably a Nick) to miss with its bomb. However, with every gun out of action except the aft 20-mm, a fourth aircraft attacked the ship and hit the Mk. 51 gun director with a bomb. A fifth aircraft identified as a Val dive-bomber dove on the ship from high altitude (with an F4U Corsair fighter on its tail), but caused no additional damage.

By 0830, the fires on LSM(R)-190 were out of control with grave risk that the rockets would explode. The order to abandon ship was given, and the wounded commanding officer and the dead gunnery officer were lowered into life rafts. At 0850, as the ship went under, there was a massive explosion. LSM(R)-190 suffered 14 dead and 18 wounded, and was the third “rocket ship” to go down in just over 12 hours, which would finally result in them being taken off radar picket duty as they would be needed for the eventual invasion of Japan. LSM(R)-190 was subsequently awarded a Navy Unit Commendation. Lieutenant Saunders was awarded a Silver Star and Ensign Tennis received a Navy Cross. His citation follows:

The President of the United States of America takes pleasure in presenting the Navy Cross to Ensign Lyle S. Tennis, United States Naval Reserve, for extraordinary heroism and distinguished service in the line of his profession while serving as Communications Officer aboard USS LANDING SHIP MEDIUM (Rocket) ONE HUNDRED NINETY (LSM(R)-190), a close-in fire support ship, in action against the enemy on 4 May 1945 off Okinawa in the Ryukyu Islands. After three enemy suicide planes crashed into his ship, wounding the Commanding Officer, he, although suffering from shrapnel wounds himself, assumed direction of the ship and calmly and efficiently maneuvered the ship and directed the firing of the anti-aircraft batteries. When it became necessary to abandon ship, he aided in evacuating his wounded Commanding Officer and was the last to leave the sinking vessel. By his outstanding initiative and inspiring leadership, he contributed materially to minimizing the number of casualties. His conduct throughout was in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.

Rear Admiral Deyo’s Flagship Birmingham (CL-62) Hit

Beginning around 0800, radars on U.S. ships in the Hagushi anchorage area, off the main Okinawa landing beaches, began to detect a massive air battle taking place off northern Okinawa, followed by signs that some Japanese aircraft were getting through. One of these ships riding at anchor was the light cruiser Birmingham (CL-62), flagship of Rear Admiral Morton Deyo, commander of Task Force 54, the Gunfire and Covering Force. Birmingham had just concluded her 41st gunfire support mission since 1 May, much of it directed at the Japanese airfield at Naha, Okinawa (still in Japanese hands at the time) to keep the Japanese from using it.

Birmingham already had a reputation as an unlucky ship. On 8 November 1943, she’d been hit by two Japanese bombs and an aerial torpedo near Bougainville in the Solomon Islands. Although casualties were relatively light at two killed and 34 wounded, the damage kept her out of the U.S. victory at the Battle of Empress Augusta Bay that evening (see H-Gram 024). Worse, on 24 October 1944, during the Battle of Leyte Gulf, Birmingham had boldly gone alongside the crippled light carrier Princeton (CVL-23) to help fight fires, when a massive explosion on on the carrier had decimated the topsides of Birmingham, killing 243 of her crew and wounding over 400 more in a scene of unbelievable carnage (see H-Gram 038). Now under the command of Captain Harry Douglas Power (who had been awarded a Silver Star in command of attack cargo ship Betelguese [AK-28] dodging multiple bombs and torpedoes off Guadalcanal in August 1942), the repaired Birmingham had rejoined the fleet in time to support the capture of Iwo Jima in March 1945.

Around 0830, radio reports indicated about 14 Japanese aircraft were being intercepted by combat air patrol about 60 nautical miles from Hagushi, but about ten or 12 made it through coming from the west. Most of these aircraft were shot down by various ships off Hagushi. At 0840, a Japanese army Oscar fighter penetrated into the anchorage and approached Birmingham, but was shot down and crashed just ahead of light cruiser St. Louis (CL-49).

At 0841, with U.S. attention focused on attacks coming from the west, a single Oscar fighter came over (or from) Okinawa undetected by radar and out of the sun. The plane was not seen by lookouts until it was less than one mile away from Birmingham, when it popped up to 4,000 feet. In a manner of seconds, the Oscar commenced a near-vertical dive from directly overhead where none of Birmingham’s 5-inch or 40-mm guns could elevate. Several 20-mm guns engaged, but lacked the stopping power to prevent the high-speed impact of the plane. It hit Birmingham’s main deck just aft and starboard of the No. 2 6-inch gun turret ahead of the bridge. The plane and its 500-pound bomb penetrated through several decks deep into the ship, wiping out the sick bay and most of the ship’s medical staff (along with many Sailors at sick call), blowing out shell plating on three decks, and holing the hull below the waterline. This flooded three ammunition magazines, the armory, and four living compartments. Despite the damage, repair parties had all fires out by 0914 and, within an hour, the most seriously wounded had already been transferred via landing craft to the hospital ship Mercy (AH-8). Birmingham suffered 52 dead and 82 wounded. She was able to get underway on 5 May to Pearl Harbor Shipyard for repairs, returning to Okinawa in late August as the war ended.

USS Shea (DM-30) Hit by Ohka Suicide Bomb

The destroyer-minelayer Shea (DM-30) had arrived at Radar Picket Station 14 about 72 nautical miles northwest of Hagushi at 0600 on 4 May, having engaged two Japanese aircraft and possibly shot one down while en route. Shea joined destroyer Hugh H. Hadley (DD-774), LSM(R)-189, and three LCS(L)s on station. She was commanded by Commander Charles Cochran “Chili” Kirkpatrick, who had already been awarded three Navy Crosses and an Army Distinguished Service Cross in command of submarine Triton for three successful war patrols in 1942 and early 1943. (Following Triton, he became aide and flag lieutenant to Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral Ernest J. King. Kirkpatrick would go on to be Superintendent of the U.S. Naval Academy in 1961–64).

Visibility was poor at RP14, limited to 5,000 yards due to smoke drifting from the smoke generators that covered the Hagushi anchorage. Shea had gone to general quarters at the first report of a large inbound raid, which appeared to bypass RP14 and go for Luce at RP12 and the Hagushi anchorage. At 0854, Shea spotted a solitary G4M Betty twin-engine bomber at the edge of the haze about six miles way. She vectored a CAP fighter to intercept, which shot the Betty down four minutes later. At 0859, a lookout on Shea sighted a very high-speed aircraft inbound from the starboard beam. The Betty had dropped its MXY-7 Ohka rocket-assisted manned suicide bomb before it had been shot down. The Betty was apparently one of two (of the seven) Ohka-carrying planes to reach a target that day. (Another Ohka barely missed the minesweeper Gayety [AM-239].)

The Ohka closed the distance so fast that only one .50-caliber machine gun, one 20-mm, and one twin 40-mm had a chance to open fire, which did no good. At over 450 knots, the Ohka crashed into Shea’s superstructure, its momentum carrying it through the sonar room and chart house, and clear out the other side of the ship before its 2,600-pound warhead exploded, thus sparing Shea from catastrophic damage. The damage was bad enough, however, as fires broke out in the combat information center, chart house, division commander’s stateroom, the mess deck, and worst, in the No. 2 upper handling room. All communications were lost, the two forward twin 5-inch gun mounts were inoperative, the main gun director was jammed, the gyro and computer were out of action, a 20-mm gun on the port side was damaged, and the ship developed a five-degree list.

Shea’s casualties were one officer and 31 enlisted men killed and 91 wounded. Nevertheless, damage control teams got the fires and flooding under control and Shea made it to Kerama Retto under her own power. She was underway for Ulithi on 15 May and transited to Philadelphia via Pearl Harbor, San Diego, and the Panama Canal. Her repairs were not completed until after the war ended. Commander Kirkpatrick was awarded a Silver Star for his actions in fighting and saving his ship.

USS Sangamon (CVE-26) Survives Devastating Kamikaze Hit

Although the main Japanese kamikaze attacks on 4 May 1945 were over by mid-morning, for the second twilight in a row, Japanese army aircraft from Formosa made an attack. This time, the target was the escort carrier Sangamon (CVE-26), a veteran of numerous battles in the Atlantic and Pacific. Sangamon had gone into Kerama Retto before dawn to replenish supplies and ammunition. Due to the numerous air raid alerts, the carrier was unable to get underway until 1830, by which time renewed cloud cover and fading light gave an advantage to the kamikaze aircraft. A large raid was reported inbound from the southwest. Four planes of this raid were shot down by Marine Corsairs, but the rest kept coming.

At 1902 a Japanese army Tony fighter made a solo attack on Sangamon. Despite heavy anti-aircraft fire from the ship and her escorts Dennis (DE-405) and Fullam (DD-474), and trailing smoke, the Tony circled around astern of Sangamon and commenced its suicide dive. It fortunately missed Sangamon by 25 feet off the starboard quarter (this resulted in one of the more famous kamikaze photos of the war, albeit blurry due to low light).

Sangamon launched two Hellcat night fighters shortly after the sun set at 1903. They were vectored after a radar contact, but found nothing and returned overhead. At 1925, Fullam reported another inbound radar contact. The Japanese aircraft was right on the deck and the fighters missed it. The Japanese plane, a twin-engine Nick fighter, dropped out of the clouds about three nautical miles from Sangamon and got a bead on the carrier before ducking back into the clouds. Finally, the plane burst out of the clouds from astern with almost no time to react. Stlll, Sangamon gunners hit it and set an engine afire, to no avail.

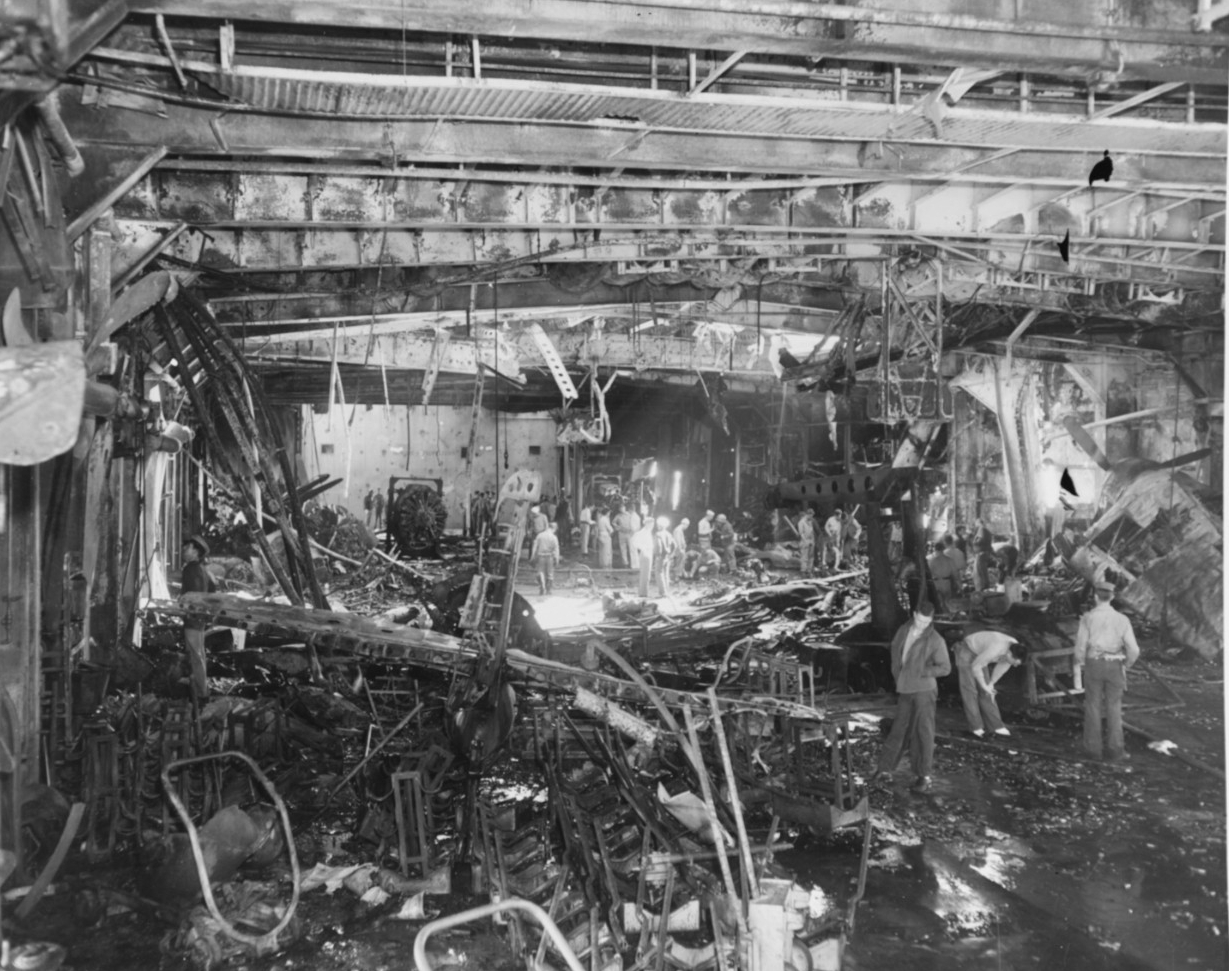

At 1933, the Nick dropped a bomb that penetrated into the hangar through the flight deck a moment before the plane crashed into and through the flight deck a little farther forward. The carrier shuddered in a massive explosion as both elevators were blown out of the wells and a large gash was ripped in the flight deck. Standard operating procedure on Sangamon was for hangar deck personnel to evacuate the hanger when guns were firing, otherwise the personnel loss would have been far worse. A number of men were blown off the ship and others jumped overboard to avoid burning in the inferno that quickly enveloped the hangar deck.

Fires on the flight deck quickly threatened the bridge, and Captain Malstrom ordered everyone off except the helmsman, navigator, his orderly, and himself, while he turned the ship out of the wind. However, communications with the bridge were lost at 1955 and Sangamon entered an uncontrolled turn until after steering regained control. At 2025, the heat and smoke were too intense, and Malstrom had to abandon the bridge and set up a control station at the forward edge of the flight deck. The intensity of the fire amidships prevented any communications between the forward and aft parts of the ship, and damage control parties at each end fought independently. The hangar deck water curtains and sprinkler system failed due to damage to water risers and valves. Although the planes in the hangar had been defueled (a hard lesson from the loss of Bismarck Sea [CVE-95] at Iwo Jima), a number were still armed and 20-mm and .50-caliber rounds cooked off.

As fires raged in Sangamon’s hangar bay, others burned on the flight deck, in some cases hampered when one team laid down foam only to have it washed away by another hose team. Aircraft on the flight deck were manually shoved over the side. LCI-61 came alongside to port to help fight the fires, but LCI-13 had her upper works smashed attempting to do the same to starboard. Destroyer Hudson (DD-475) then came alongside and also suffered topside damage. She avoided catastrophe when a burning plane fell off the flight deck onto her depth-charge rack, where quick-thinking and very brave Sailors shoved the flaming aircraft overboard before the depth charges detonated.

By 2200, in yet another great U.S. Navy damage control story, all fires were under control. The hangar deck was burned out, the flight deck was unusable as was the island, and only one aircraft survived undamaged. Yet the ship was still afloat, having survived a fire worse than on any other escort carrier during the war. However, 46 men were dead and 116 wounded. One factor was that the four Sangamon-class escort carriers were converted from U.S. Navy tankers, unlike later escort carriers that were either converted merchant hulls or designed based on merchant hulls, with far less built-in survivability. Other factors were that all the planes had been defueled, the hangar bay had been cleared of personnel before the hits, and every member of the crew had been well trained in firefighting. Captain Malstrom summed it up, “Again it has been proved that firefighting school is worth all the man-days it requires.” Nevertheless, although she survived, Sangamon was out of the war and she would never be fully repaired.

Malstrom was awarded a Silver Star for his heroism in saving the ship. I include the section here as an example of how hard it is to discern the level of bravery between a Navy Cross and a Silver Star:

The President of the United States of America takes pleasure in presenting the Silver Star to Captain Alvin Ingersoll Malstrom, United States Navy, for conspicuous gallentry and intrepidity as Commanding Officer of USS SANGAMON (CVE-26) during operations against enemy Japanese forces in the vicinity of Okinawa on 4 May 1945. When his ship was severely damaged by an enemy suicide plane and raging fires broke out on the hangar deck and among gassed and armed planes on the flight deck, Captain Malstrom directed the fire fighting operations from the bridge until the island structure was enveloped in flames, causing intense heat and suffocating smoke. Beset by darkness, low water pressure caused by broken risers and temporary loss of electrical power, as well as complete absence of communications, he continued to direct overall firefighting operations which resulted in the saving of his ship. By his leadership, courage and devotion to duty, Captain Malstrom upheld the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.

British Carrier Force (TF 57) Hit by Kamikaze on 4 and 6 May 1945

The British carrier force operating southwest of Okinawa had also come under kamikaze attack on 4 May. Under the overall command of Vice Admiral Sir H. Bernard Rawlings, Task Force 57 included the battleships HMS King George V and Howe, and the five carriers of CTG 57.2 (HMS Indomitable, Victorious, Illustrious, Indefatigable, and Formidable) under the command of Rear Admiral Sir Philip Vian. On the morning of 4 May, the battleships and some cruisers and destroyers were detached to bombard Japanese airstrips in the Sakishima Islands (between Okinawa and Formosa). While the carrier screen was thus weakened, about 16–20 Japanese aircraft attacked, some of them serving as decoys.

At 1131, a Zeke made it through an intense anti-aircraft barrage and struck Formidable near her island, starting a large fire among aircraft on the flight deck. Splinters passed through a small hole in the armored flight deck into the center boiler room, which resulted in a temporary reduction in speed. Formidable suffered 18 killed and 47 wounded with 11 aircraft destroyed, but the armored flight deck did its job. It was patched by the afternoon and Formidable resumed operations. At about the same time Formidable was hit, another Zeke attacked Indomitable, finally being brought down only ten yards from her bow.

At 1654 on 6 May, Victorious was hit twice in quick succession by two kamikaze before she shot down a third. Shortly afterward, at 1705, Formidable was hit again and another seven of her aircraft were destroyed, leaving her with only 15 operational aircraft. Both Formidable and Victorious temporarily withdrew for quick repairs. The armored flight decks on the British carriers helped minimize damage. The primary trade-off was that British carriers could only embark about 50 aircraft compared to almost 100 on U.S. Essex-class carriers.

Kikusui No. 5 Summary

Over 90 Americans sailors died during the kamikaze attacks on 3 May and about 490 were killed on 4 May, making this the deadliest two-day total of the Okinawa campaign for the U.S. Navy, and there would be more to follow that were almost as bad. The attacks during these two days had cost three destroyers and three LSM(R)s sunk. Other ships, including an escort carrier, light cruiser, and other destroyers were knocked out of the war by heavy damage. Nevertheless, although the LSM(R)s were scarce, destroyers and light cruisers were abundant, and the losses represented a very small percentage of the U.S. Navy forces committed to the fight at Okinawa. The high casualties, however, reverberated to the highest level of U.S. Navy command. Even Fleet Admiral Nimitz and his deputy chief of staff, Rear Admiral Forrest Sherman, had a bout of dismay when informed of the losses. Sherman predicted that high losses would continue. Nimitz nevertheless steeled his resolve by saying, “Anyway, we can produce new destroyers faster than they can build planes.” The cost in people, over 580 killed in two days, weighed heavily on Nimitz’ mind as he contemplated the casualties expected in an invasion of Japan, and the several thousand aircraft the Japanese were believed to be holding back for the ultimate defense of the Japanese home islands.

Sources include: Kamikaze Attacks of World War II: A Complete History of Japanese Suicide Strikes on American Ships by Aircraft and Other Means, by Robin L. Rielly (Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Co., Inc., 2010); Desperate Sunset: Japan’s Kamikazes Against Allied Ships, by Mike Yeo (London: Bloomsbury Press, 2019); The Little Giants: U.S. Escort Carriers Against Japan, by William T. Y’Blood (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1987); NHHC Dictionary of American Fighting Ships (DANFS); and History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, Vol. XIV: Victory in the Pacific, by Samuel Eliot Morison (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1961).