H-Gram 072: The 80th Anniversary of the Battle of Midway

26 May 2022

Download a PDF of H-Gram 072 (3.8 MB).

Overview

This H-gram for the 80th anniversary of the decisive Battle of Midway (4–7 June 1942) reprises some of what I wrote for the 75th anniversary (H-Gram 006), with the addition of more detail on the incredibly heroic action of the Midway-based TBF Avenger torpedo bomber detachment of Torpedo Squadron 8 (VT-8) led by Lieutenant Langdon Fieberling. Fieberling’s decision to attack at once set in motion the sequence of events leading to the destruction of the Japanese carrier force.

The Battle of Midway—80th Anniversary

I wrote extensively about the Battle of Midway five years ago. So, in this edition, I’d like to highlight the actions of the VT-8 detachment on Midway Island, led by Lieutenant Langdon Fieberling, as an example of how the actions of one junior officer altered the course of the battle—and of World War II. Fieberling set in motion a sequence of events that resulted in one of the most decisive battles in all of naval history. The price was high: five of six aircraft and the lives of 16 of 18 men, including Fieberling’s own.

Launching from Midway Island early on 4 June 1942 upon warning of an inbound Japanese carrier air strike, Fieberling led his detachment of six new state-of-the art TBF-1 Avenger torpedo bombers directly to the Japanese carriers, becoming the first U.S. aircraft to attack that force of four aircraft carriers and two battleships. Almost simultaneously, a group of four U.S. Army Air Forces B-26 bombers from Midway, each rigged with a torpedo, caught up to the TBFs.

The TBFs went for carrier Hiryu and the B-26s went for the flagship carrier Akagi. The U.S. aircraft ran into a buzz saw of 30 Japanese Zero fighters and intense anti-aircraft (AA) fire from escorting battleships and cruisers. However, it was the Japanese, flush with a six-month victory spree, who were shocked when the two types of aircraft they had never seen before refused to go down despite absorbing massive battle damage. In fact, the first planes to go down in flames were two Japanese fighters. Nor did any of the American aircraft turn away, despite the overwhelming odds, an equally shocking act of bravery to the Japanese.

One severely damaged TBF was forced to veer out of formation, but took a torpedo shot at the light cruiser Nagara (this would be the only TBF to survive). However, five TBFs and all four B-26s made it through the initial fighter defense and the AA fire of the escorts. Now increasingly desperate, Japanese fighters had to fly through the anti-aircraft fire of their own ships in order to inflict enough cumulative damage to start bringing down the U.S. aircraft, which still kept coming. Two of the TBFs got close enough to Hiryu to launch torpedoes, which were so slow that the carrier outran them. Two B-26s launched two torpedoes at Akagi, which her skipper adroitly avoided. One the B-26s buzzed and strafed the length of Akagi’s flight deck before escaping. A third crippled B-26 narrowly missed hitting Akagi’s bridge—a few feet lower and Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo and his entire staff would have been wiped out.

The attack was recorded in history as a “failed” and futile effort: of ten planes, seven were lost, for no hits. For the Japanese and Vice Admiral Nagumo, it was a different story: ten planes exhibiting samurai-like bravery had penetrated through 30 fighters and multiple escorts to get four torpedoes dangerously close to two of his carriers. Moreover, he had been through the near-death experience from the B-26 (named “Satan’s Playmate”) that had barely missed Akagi’s bridge before it crashed.

Nagumo needed no further convincing that the obviously very real threat from Midway Island was more important than a hypothetical threat from any U.S. aircraft carrier that Japanese scouts had yet to find. This resulted in perhaps the most second-guessed decision in all of naval history when he ordered his reserve strike of 107 aircraft re-armed for a second strike on Midway, setting in motion a cascading series of problems for the Japanese carriers, especially after a U.S. carrier was finally sighted.

The attack by the TBFs and B-26s also initiated another sequence of events when the smoke of the battle attracted the submarine USS Nautilus (SS-168). In an incredible act of courage—despite being strafed, bombed, depth-charged and forced deep multiple times—Lieutenant Commander William Brockman kept bringing Nautilus back into position in order to attack the Japanese force. Finally, in frustration, the Japanese destroyer Arashi remained behind to keep Nautilus pinned down while the Japanese carrier force moved away.

As the Japanese virtually annihilated all three U.S. carrier torpedo squadrons one after the other, and both strike packages from Hornet (CV-8) and Enterprise (CV-6) had overshot the Japanese and were critically low on fuel, Lieutenant Commander Wade McClusky, leading the Enterprise air group strike, sighted Arashi trying to catch up to the Japanese carrier group. As a result, in another 20 minutes, three of the four Japanese carriers were mortally wounded and unable to conduct flight operations. This turned the tide of the Pacific War and changed the course of World War II in one of the most lopsided victories in the history of naval warfare.

Although other heroes of the Battle of Midway are more famous, such as Wade McClusky, Dick Best, Dusty Kleiss, John Waldron, Jimmie Thach, and George Gay, Langdon Fieberling clearly understood the “do or die” nature of the battle against an overwhelming force that was essentially undefeated to that point. He did what he had to do and did his duty to the fullest; his gallantry and that of the rest of the VT-8 detachment deserves to be remembered. For more on Lieutenant Fieberling and the attack of the VT-8 Midway detachment, please see attachment H-072-1.

Grumman TBF-1 (BuNo. 00380) Avenger of Torpedo Squadron 8 (VT-8), photographed at Midway, 25 June 1942, prior to shipment back to the United States for post-battle evaluation. Badly shot-up, this plane was the only survivor of six Midway-based VT-8 TBFs that had attacked the Japanese carrier force in the morning of 4 June. The plane's pilot was Ensign Albert K. Earnest. Crew were Radioman Third Class Harrier H. Ferrier and Seaman First Class Jay D. Manning. Manning, who was operating the .50- caliber machine-gun turret, was killed in action with Japanese fighters during the attack (80-G-17063).

A Short Summary of the Battle

The commander’s estimate of the situation in the Japanese Midway operations order indicated that “…the enemy lacks the will to fight….” This assumption was the Japanese navy’s biggest mistake.

The Battle of Midway was one of the most critical battles of World War II, and one of the most one-sided battles in all of history, although at a very high cost for the U.S. pilots and aircrewmen who gained the victory. It was not, however, a “miracle.” On 4 June 1942, four Japanese aircraft carriers faced off against three U.S. aircraft carriers and an island (248 Japanese aircraft to 360 U.S. aircraft). None of the remainder of the overwhelming Japanese force was in a position to affect the outcome of the battle. The reason was because Japanese Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto had a bad plan based on faulty intelligence, and a gross underestimation of American will to fight. An unbroken six-month victory spree had also made the Japanese over-confident (the Japanese thought they sank both U.S. carriers engaged in the Battle of the Coral Sea on 8 May 1942).

Admiral Chester Nimitz, on the other hand, had a good plan based on exceptional intelligence that gave the U.S. the crucial element of surprise. Like almost everyone in the U.S. Navy at the time, Admiral Nimitz overestimated U.S. operational and tactical prowess relative to the Japanese (Pearl Harbor was not seen as a “fair” fight). Based on intelligence derived to a significant degree from breaking some of the Japanese navy operational code (JN-25B), Nimitz had good reason to believe that he was taking a “calculated risk” with a reasonable chance of success. He did not believe he was making a “desperate gamble” (as is often portrayed) with the precious remaining U.S. aircraft carriers when he ordered Yorktown (CV-5), Enterprise, and Hornet to a position from which to ambush the Japanese carrier force during the expected attack by Japanese aircraft on Midway Island.

As a result, at 0900 on 4 June, as half the Japanese aircraft were returning from the strike on Midway, the commander of the Japanese carrier task force, Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo, had no clue that 152 U.S. carrier aircraft were already en route to attack him (only at 0820 did he even know one U.S. carrier was in the area). Nevertheless, the U.S. force almost blew it, because at 0900, 77 of those aircraft were heading in directions that would miss the Japanese carriers entirely, and had already fractured into at least seven uncoordinated groups.

Meanwhile, the first waves of U.S. torpedo and dive-bombers originating from Midway Island were being slaughtered in multiple, separate, extremely valiant but futile attacks on the Japanese carriers. However, the courage of these attacks (including the B-26 that nearly killed Nagumo and his staff), and surprisingly heavy Japanese losses to U.S. Marine Corps fighters and ground fire at Midway Island, instigated Nagumo’s fateful decision to re-arm his 107-plane reserve strike with land-attack in place of anti-ship weapons—before he received a first aircraft sighting report on one of the U.S. carriers.

As the Japanese tried frantically to shift back to anti-ship weapons, three successive waves of U.S. TBD Devastator torpedo bombers attacked the Japanese carriers with mind-boggling courage. Not one of the 41 Devastators turned away before being shot down or dropping a torpedo; only three would make it back to their carriers. The protracted sacrifice of the Midway aircraft and the carrier torpedo bombers prevented the Japanese from spotting their counter-strike aircraft on deck, which ultimately prevented the Japanese from inflicting severe damage on the U.S. force.

To the extent there was a “miracle” at Midway, it was a freak sequence of events. Smoke from the first attack on the Japanese carriers by the Midway-based aircraft drew the attention of submarine Nautilus, which then barely survived multiple depth-charge attacks while trying unsuccessfully to attack the Japanese carriers. The destroyer Arashi was ordered to stay behind and keep the pesky submarine under. It was Arashi’s high-speed return to the carrier force that caught the attention of Lieutenant Commander Clarence Wade McClusky, who was leading a 33-plane SBD Dauntless dive-bomber strike from Enterprise that had overshot the Japanese.

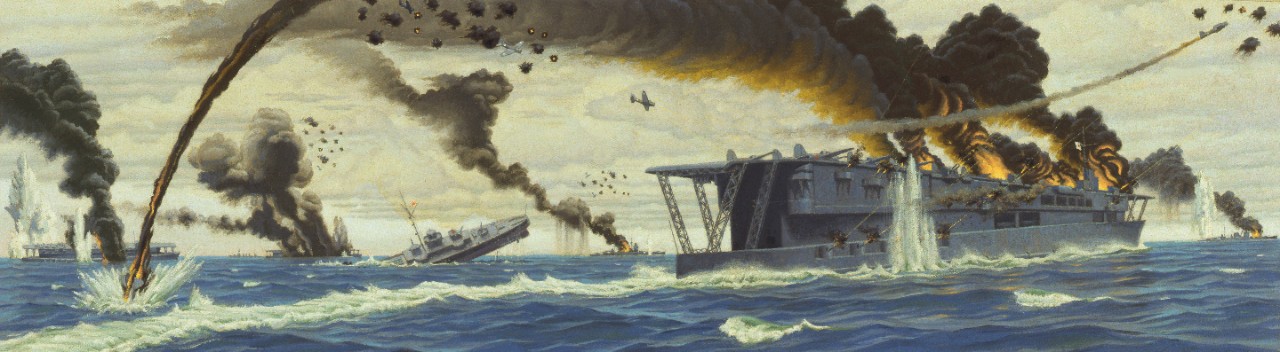

Following the Arashi’s course, and by sheer coincidence, the Enterprise strike arrived over the Japanese carriers at the same time as 17 dive-bombers from Yorktown. With the Japanese fighter cover out of position finishing off the torpedo bombers, the carriers Akagi, Kaga and Soryu were mortally damaged by dive-bombers within the space of five minutes. Hiryu would get off two strikes that would cripple Yorktown before the Enterprise and Yorktown dive-bombers inflicted fatal damage to her. Yorktown and destroyer Hammann (DD-412) were sunk by Japanese submarine I-168 on 6 June and, that same day, Japanese heavy cruiser Mikuma was sunk by U.S. dive-bombers.

Although over 75 percent of the Japanese naval aviators actually survived the battle to fight again, the loss of four irreplaceable carriers and the highly skilled maintainers altered the course of the war. Over 3,000 Japanese died at Midway. The Japanese surface navy didn’t get the memo that the tide of war had turned, so many months of bitter battles lay ahead in the waters around Guadalcanal that would cost the U.S. Navy almost 5,000 dead. U.S. deaths at Midway were “only” 307, but of the carrier aircraft that actually made contact with the Japanese on 4 June, over 40 percent were shot down or ditched due to battle damage or running out of fuel. Over 150 naval aviators paid the ultimate price for this decisive victory.

As noted above, H-Gram 006 provides an in-depth account of the battle. H-006-1 provides a more detailed overview. H-006-2 details the U.S. Navy codebreaking and intelligence analysis, as well as the failure of the Japanese reconnaissance and scouting effort. H-006-3 provides insights on the costly attacks by the Midway-based aircraft and the three carrier-based torpedo squadrons. H-006-4 describes the decisive U.S. dive-bomber attacks that caused the loss of all four Japanese carriers, as well as the ultimate loss of Yorktown to a Japanese submarine.

Japanese aircraft carrier Hiryu burning, shortly after sunrise on 5 June 1942, a few hours before she sank. Photographed by a plane from the carrier Hosho. Note collapsed flight deck at right. Part of the forward elevator is standing upright just in front of the island, where it had been thrown by an explosion in the hangar (NH 73064).

USS England (DE-635)

Although a little off topic, a group of retired senior flag officers (H-gram readers) made a special request that I highlight the 78th anniversary of the incredible feat of the destroyer escort England in sinking six Japanese submarines in the space of 12 days from 19 May to 30 May 1944, an unprecedented accomplishment in the U.S. Navy. Due to a combination of extraordinary intelligence cueing and tactical prowess with the “hedgehog” anti-submarine mortar system, England sank I-16, RO-106, RO-104, RO-116, RO-108, and RO-105, essentially wiping out an entire submarine reconnaissance line and delaying Japanese reaction to the U.S. invasion of the Marianas Islands. England was awarded a Presidential Unit Citation and ten Battle Stars before she was knocked out of the war by a kamikaze hit off Okinawa on 9 May 1945. Despite the death of 37 personnel and the wounding of another 25, she was saved due to the extraordinary damage control of her crew.

The Chief of Naval Operations, Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King, was so impressed by England’s performance against the submarines that he declared, “There will always be an England in the United States Navy.” Despite King’s promise, this has not been true since guided-missile cruiser England (CG-22) was decommissioned in 1994. See H-Gram 030/H-030-1 for more on England.

USS England (DE-635): Damage from a kamikaze hit received off Okinawa on 9 May 1945. This view, taken at the Philadelphia Navy Yard, Pennsylvania, on 24 July 1945, shows the port side of the forward superstructure, near where the suicide plane struck. Note scoreboard painted on the bridge face, showing the ship's Presidential Unit Citation pennant and symbols for the six Japanese submarines and three aircraft credited to England. Also note fully provisioned life raft at right (80-G-336949).

Last Survivor of USS Johnston (DD-557) Passes

On a separate sad note, the last surviving member of the heroic crew of the destroyer Johnston passed away on 7 May 2022. Carlos Cerna, 101, was a yeoman second class aboard Johnston when Commander Ernest Evans ordered his ship on the epic single-handed daylight torpedo attack against an overwhelming force of Japanese battleships, heavy cruisers and destroyers off Samar during the Battle of Leyte Gulf. This action earned Evans a posthumous Medal of Honor and the ship a Presidential Unit Citation. Johnston went down fighting to the last in what many believe was the most gallant action in the history of the U.S. Navy. At Johnston’s commissioning, Evans had said at that he would never run from a fight, and anyone who didn’t want to go along had better get off the ship. Carlos (along with the entire crew) stayed aboard, and our nation owes them a debt of gratitude today for their role in defeating tyranny during World War II. (And, if you want to know what I think of the ship, my license plate frame reads “USS JOHNSTON DD-557.”) See H-Gram 036 for more on Johnston and Ernest Evans.

As always, previous H-grams may be found here—feel free to share.