Hornet VII (CV-8)

1941–1943

VII

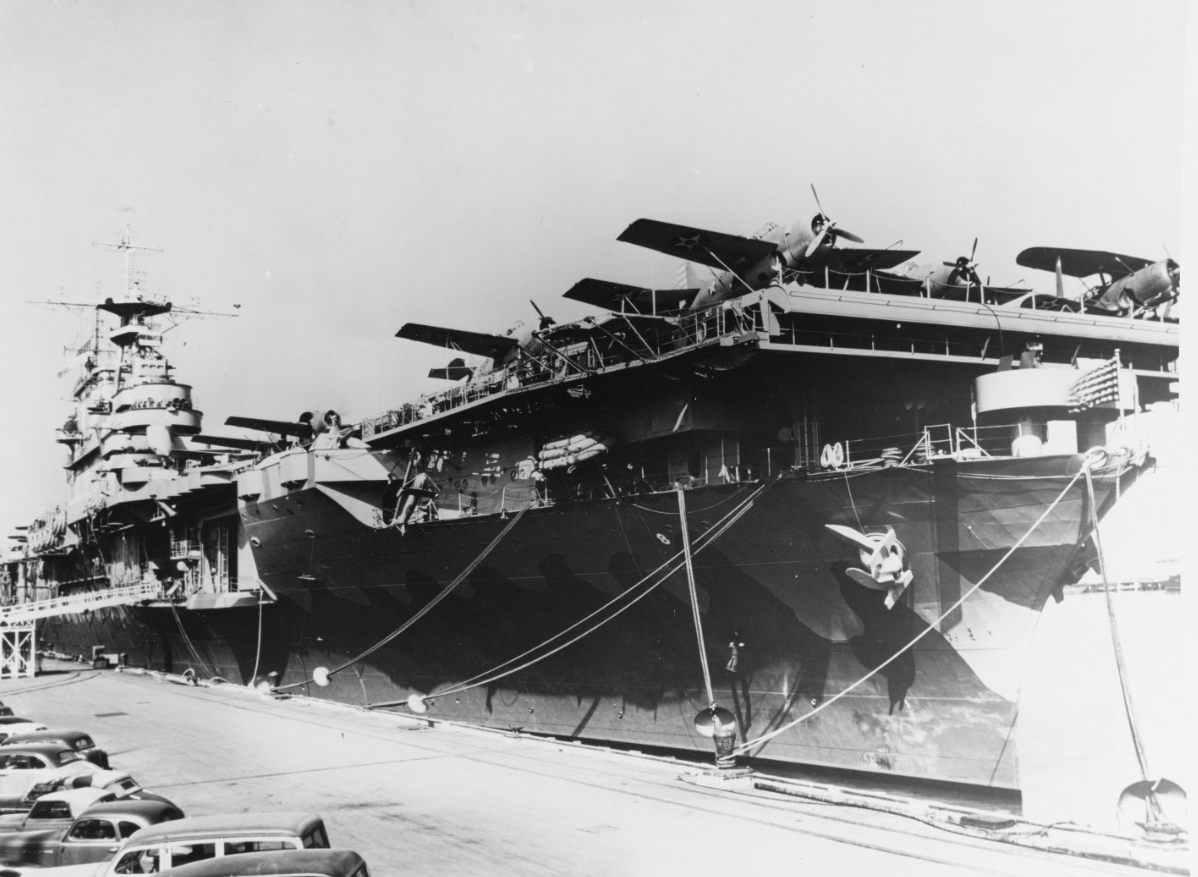

(CV-8: displacement 19,800; length 809'9"; beam 83'1"; extreme width (flight deck) 114'0"; draft ; speed 32.5 knots; complement; aircraft 80-85; armament 8 5-inch, 16 1.1-inch, 16 .50 caliber; class Yorktown)

The seventh Hornet (CV-8) was laid down on 25 September 1939 at Newport News, Va., by Newport News Shipbuilding & Dry Dock Co.; launched on 14 December 1940; sponsored by Mrs. William F. Knox, wife of Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox; and commissioned on 20 October 1941 at the Naval Operating Base (NOB), Norfolk, Va., Capt. Marc A. Mitscher in command.

Hornet shifted to the Norfolk Navy Yard, Portsmouth, Va., on the afternoon of 24 October 1941, then entered dry dock no. 4 on 16 November, remaining there until undocking on the 23rd. She returned to NOB Norfolk on the morning of 6 December. The next afternoon [7 December], after Japan initiated hostilities in the Pacific on a broad front, including a daring attack on the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, T.H., Hornet’s deck log noted the ship receiving a dispatch from the Secretary of the Navy at 1435: “execute WPL 46 against Japan.” The ship immediately began “taking necessary additional security measures.”

Hornet stood out of NOB Norfolk and anchored in Lynnhaven Bay on the afternoon of 10 December 1941, then steamed over the degaussing range the following day. She anchored in Hampton Roads, then in Chesapeake Bay, over the following days, running magnetic compass compensation on the 15th. Hornet, with Noa (DD-343) as her plane guard, carried out aircraft launching and recovery operations on the 16th, and also conducted structural firing tests of all of her guns, from her 5-inch mounts to the 1.1-inch and the 20-millimeters. While conducting flight operations on 17 December, Hornet received a report from Noa that the latter had made what she believed to be a submarine contact and attacked, dropping two depth charges with no observable results. Hornet anchored off the Wolf Trap Range later that afternoon, then returned to NOB Norfolk on the 19th.

Steaming into Hampton Roads on 24 December 1941, Hornet stood out on the morning of 27 December in the wakes of the battleships Washington (BB-56), flying the flag of Commander Battleships Atlantic Fleet, and North Carolina (BB-55), Battleship Division (BatDiv) 6, accompanied by Noa and the high-speed minesweepers [converted destroyers] Stansbury (DMS-8) and Hogan (DMS-6), setting course for the Dry Tortugas and shakedown training. On the 29th, Hornet provided two Curtiss SBC-4s from Scouting Squadron (VS) 8 to fly inner anti-submarine patrol over the battleships.

During the first watch on 29 December 1941, Hornet separated from Washington and North Carolina and their escorts and rendezvoused with Noa. On 31 December, Lt. (j.g.) William H. Hilands, A-V(N), of VS-8, crashed astern during recovery operations, his SBC-4 (the air group’s only spare) sinking almost immediately. Noa recovered the pilot, and Hornet transferred Lt. (j.g.) Felix H. Ocko, MC, the air group flight surgeon, to the destroyer via motor whaleboat. Ocko reported that Hilands had suffered a possible skull injury in addition to facial lacerations, but that his condition was good. That afternoon, Hornet’s lookouts sighted a sailing vessel, and Capt. Mitscher ordered Noa to investigate, the destroyer identifying the stranger as the fishing boat Ysa Belita, Willie Floyd, master, five days out of Key West. Soon thereafter, a motor whaleboat returned the flight surgeon to the carrier.

Hornet’s shakedown, as Capt. Mitscher later reported, proved “fruitful and productive,” confidently informing Adm. Harold R. Stark, the Chief of Naval Operations, that his ship was “ready for war at any time, at any place” provided she received her full complement of planes. Hornet had put in “concentrated work” since clearing Hampton Roads, and once she reached the Gulf of Mexico, operated largely independently of the battleships with Noa. The carrier ran a full power trial, conducted damage control drills and exercises about every two days, and exercised her gun batteries.

Hornet’s air department carried out intensive operations that ran the gamut of aerial gunnery, dive bombing, and simulated torpedo attacks, almost daily. While Mitscher – Naval Aviator No. 33 -- had considered the Hornet Air Group’s pilots “as well trained as those on any carrier” he had served in, averaging only 360 hours in the air when they joined the ship at Norfolk, some were hardly dry behind the ears. Most had never been on board a ship and some, Mitscher noted wryly, “probably had never seen a ship before.” Rejoining BatDiv 6 and its escorts, Hornet returned to the Tidewater area, standing in to Hampton Roads on 31 January 1942.

While Hornet had been shaking down, a “joint Army-Navy bombing project” -- to bomb Japanese industrial centers, to inflict both “material and psychological” damage upon the enemy – had been conceived. Planners hoped that the former would include the destruction of specific targets “with ensuing confusion and retardation of production.” Those who planned the attacks on the Japanese homeland hoped to induce the enemy to recall “combat equipment from other theaters for home defense” and incite a “fear complex in Japan.” Additionally, it was hoped that the prosecution of the raid would improve the United States’ relationships with its allies and receive a “favorable reaction [on the part] of the American people.”

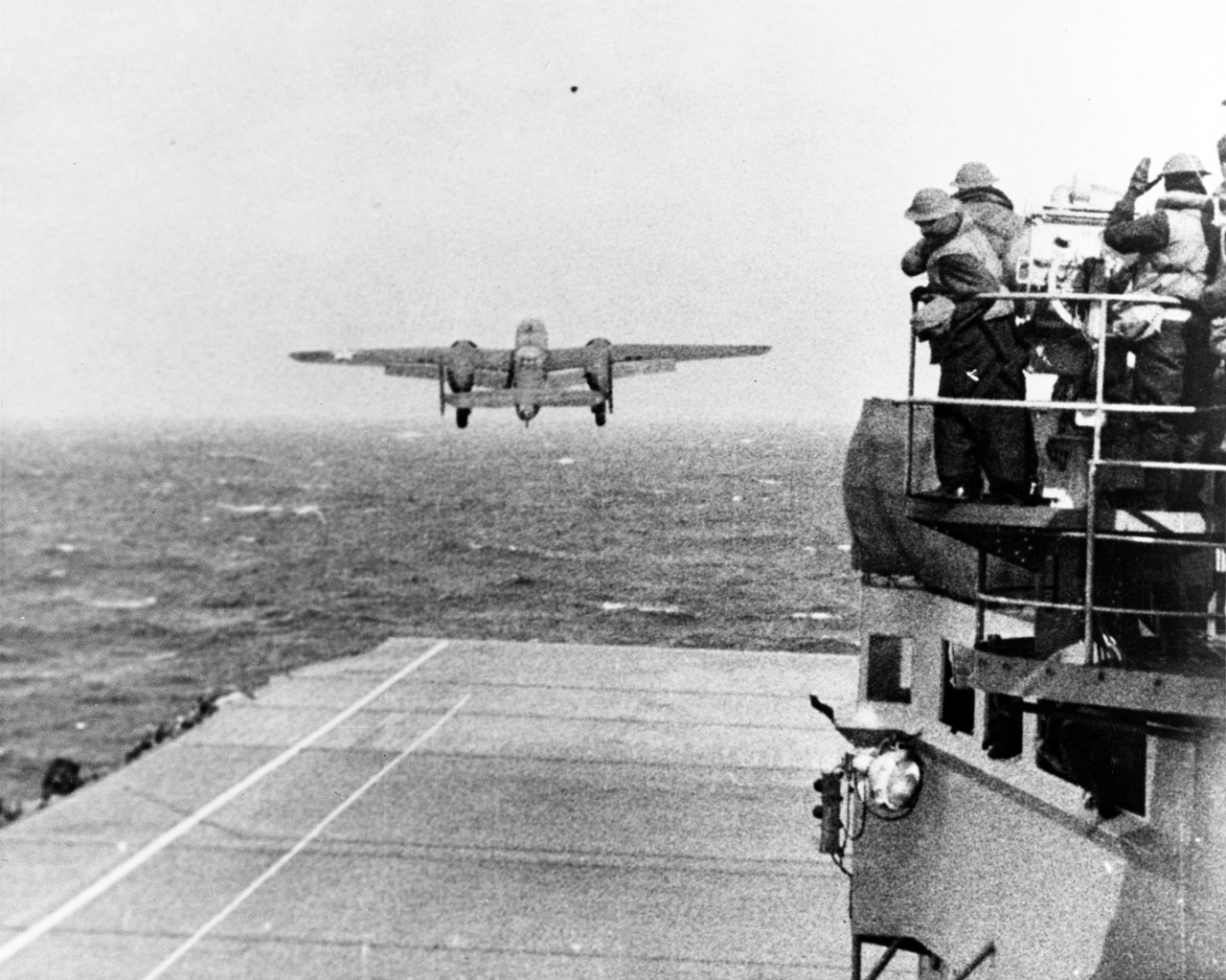

Hornet lay moored alongside Pier 7, NOB Norfolk, the following day [1 February 1942], where Capt. Mitscher received Capt. Donald B. Duncan, air operations officer on the staff of Adm. Ernest J. King, Commander in Chief, U.S. Fleet (ComInCh) since the “joint Army-Navy bombing project” envisioned the use of USAAF medium bombers to be launched from, and recovered by, an aircraft carrier. Research had disclosed the North American B-25 Mitchell to be “best suited to the purpose,” the Martin B-26 Marauder possessing unsuitable handling characteristics and the Douglas B-23 Dragon having too great a wingspan to be comfortably operated from a carrier deck. Duncan queried Mitscher if a B-25B could take off from his ship’s flight deck. When informed of how many were being contemplated for eventual deployment – 15 – Mitscher said that it could be done. Duncan then confided to Mitscher that his ship had been selected to participate in a test to see whether or not such an evolution could be carried out. Duncan, however, provided nothing more.

Consequently, on 2 February 1942, Hornet brought on board two B-25Bs and later that day stood out of Hampton Roads for the waters off the Virginia capes. The two Mitchells -- the first flown by Lt. John E. Fitzgerald, USAAF, and the second by Lt. James F. McCarthy, USAAF – took off without mishap and Hornet returned to port, entering the Norfolk Navy Yard for post-shakedown repairs and alterations that included new camouflage – Measure 12 (mod.), then returned to Pier 7 at NOB Norfolk, where, an hour before midnight on 3 March, she embarked Assistant Secretary of the Navy for Air Artemus Gates and an aide, who were to travel in the carrier to observe operations. Hornet, fueled and provisioned, with her air group embarked, then cleared Pier 7 at 1005 and maneuvered out into the stream, anchoring in Hampton Roads at 1037. Underway again shortly after noon on 4 March, Hornet sailed from the Tidewater region as part of Task Force (TF) 18 in company with Cimarron (AO-22), the destroyer Gwin (DD-433), high speed transport Manley (APD-1), the steamship Santa Ana, and joined after the carrier had dropped her pilot after passing Cape Henry, destroyers Grayson (DD-435) and Meredith (DD-434).

The next morning, 5 March 1942, the rest of the task force that Hornet would accompany hove into sight, but during recovery operations, 8-S-12, a Curtiss SBC-4 (BuNo 4122) piloted by Ens. Max E. Gregg, A-V(N), crashed astern of the ship and sank immediately. Gregg’s passenger extricated the stunned pilot from the sinking plane and kept him afloat until the destroyer Sturtevant (DD-240) retrieved them from the sea.

The task force continued on, course set for Panama, ships that included heavy cruiser Vincennes (CA-44) and light cruiser Nashville (CL-43), and destroyer Monssen (DD-436), as well as the U.S. Army Transports (USAT) Santa Lucia, Santa Paula, and Uruguay. Flight operations continued unabated during the passage. Twenty minutes into the second dog watch on 9 March 1942, one of Torpedo Squadron (VT) 8’s Douglas TBD-1 Devastators, 8-T-5, hooked the number 8 wire that snapped and flailed about the deck, injuring four men – two sailors and two marines from the ship’s Marine Detachment. The next afternoon [10 March 1942] Hornet launched one of her utility planes to transport Assistant Secretary of the Navy for Air Gates, and his aide, to shore, the cruise in the carrier having been completed.

Transiting the Panama Canal on 11 March 1942, Hornet cleared Balboa the following morning, and that afternoon (1549) brought on board Cox. W. R. LaBuron, F3c L. R. Masella, and AS Joseph E. Durik, the last gravely injured, from Meredith, along with Lt. John S. Peek (MC), who was embarked to assist in their care. The three enlisted men had been hurt when a torpedo was accidentally fired on board the ship. Despite the best efforts of all involved, however, AS Durik died during the mid watch (0225) on 15 March. At 1335 funeral services began for Durik, and at 1345 Hornet stopped her engines. One minute later, Durik’s body was committed to the deep with full military honors. Soon thereafter, the carrier resumed the voyage, “all engines ahead standard, 16 knots.”

Hornet and her consorts reached San Diego, Calif., on 20 March 1942, and after standing through the swept channel, moored at NAS North Island. She then got underway on the morning of the 23rd to conduct carrier qualifications, during which 8-F-2 crashed into the barrier at 1655 and burst into flames, Ens. Robert A. M. Dibb, A-V(N), the pilot, scrambled free of the burning Wildcat with superficial burns on his face and left wrist, and a lacerated right wrist. The ship went to fire quarters at 1657, the fire party extinguishing the blaze by 1710. Less than 20 minutes later, Hornet resumed the recovery process, the landing signal officer bringing the last plane on board at 1741. The next day [24 March], however, the carrier lost two more F4Fs, when Ens. Mortimer V. Kleinmann, Jr., A-V(N), ditched 8-F-14 at 0742, the pilot suffering a two-inch gash on his forehead in the water landing. Ens. Harold J. W. Eppler, A-V(N), crashed upon landing and 8-F-13 went over the side into the water. Grayson rescued the pilot uninjured.

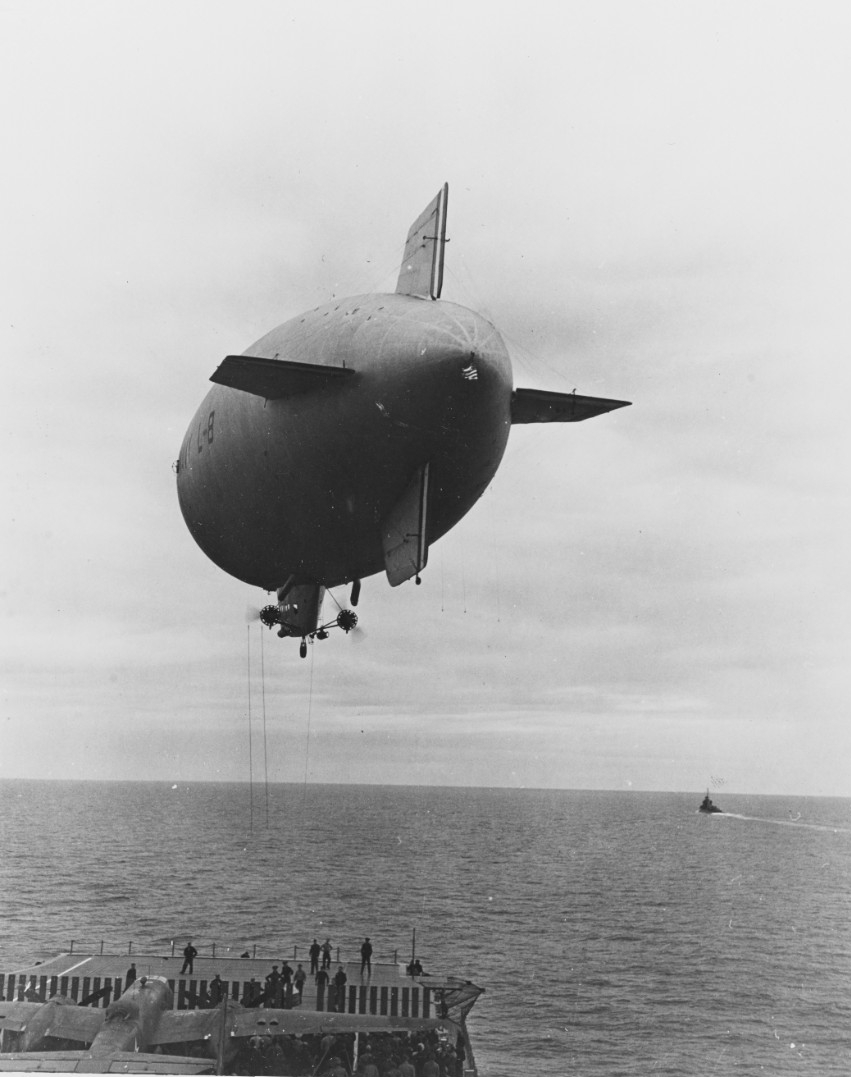

Mid-way through the first dog watch on 31 March 1942, tugs assisted Hornet alongside Pier 1, NAS Alameda, where, on 1 April, the carrier loaded 16 B-25s that had been stripped of everything not deemed essential. Capt. Duncan visited the ship, informing her commanding officer that Hornet was to take the B-25s to bomb Japan. Later that day, Hornet – “a great floating ark of tension, eagerness, and scuttlebutt” – hauled in her lines and moved away from the pier, then anchored in San Francisco Bay shortly before the end of the afternoon watch. After fueling, she got underway at 1018 on 2 April from San Francisco and stood out into the Pacific, Nashville, Vincennes, and Cimarron falling in astern of her, destroyers Gwin, Grayson, Meredith, and Monssen deployed as screen. Later that afternoon, the non-rigid airship L-8 rendezvoused with the force and delivered two packages, containing navigator’s domes for the B-25s, onto the carrier’s flight deck.

With Hornet’s flight deck unusable, Vincennes and Nashville launched and recovered floatplanes during the passage. Vincennes lost a man overboard in the heavy seas on 6 April 1942, but Meredith rescued the fortunate sailor 12 minutes later. Cimarron fueled the screening ships as necessary, and as weather permitted. Three days later [9 April], on the same day that the sea proved too rough for Hornet to take on fuel from Cimarron, a wave swept a man overboard from the oiler; Meredith again rushed to the rescue, retrieving the sailor from the heavy sea in ten minutes.

TF-18 crossed the 180th meridian during the morning watch on 13 April 1942, thus losing 14 April in the process. Soon thereafter, Hornet and her consorts formed up with TF-16, formed around Enterprise (CV-6), Vice Adm. William F. Halsey, Jr., as the officer in tactical command (OTC). Enterprise provided the “eyes” for the task force, along with the SOCs from the cruisers. On all but the worst days, her planes scouted and patrolled as the task force plunged onward, its passage providentially cloaked in bad weather. Halsey provided operations orders and data to Hornet, including were three medals, awarded to U.S. sailors when the Great White Fleet visited Japan who were (in 1942) defense workers, who asked that their decorations be returned to Japan attached to a bomb.

On 17 April 1942, Hornet took on board 200,634 gallons of fuel from Cimarron (0658-0805), after which the oiler replenished Northampton (CA-26) and Salt Lake City (CA-25). Later that afternoon, Halsey detached the oilers and the destroyers, retaining the cruisers for the final run-in to the launch point.

A northwesterly wind blew raw and cold over a rough, gray sea as dawn broke on 18 April 1942. At 0508, Enterprise began launching an inner air patrol and a combat air patrol, completing the evolution at 0522. At 0738, however, alert lookouts spotted No. 23 Nitto Maru, a guardboat of the Second Squadron that had been relieved on station the previous day and was heading for her home port of Kushiro, bearing 216°, 15,000 yards distant, and she changed course ten minutes later. Soon thereafter, Vice Adm. Halsey ordered Nashville to sink the Japanese ship, a task that proved easier to order than to execute, for Nashville had a difficult time keeping the ship – which actually managed to get off six contact reports all told -- in sight in the heavy seas.

Although the original operation plan had called for a launch 500 miles off the Japanese coast, No. 23 Nitto Maru’s sighting of TF 16 dictated that the 16 B-25s be launched immediately, approximately 650 miles out. Consequently, Hornet changed course into the wind, working up to 15 knots at 0803, 20 knots at 0810, and 22 knots at 0814; seven minutes later, Lt. Col. Doolittle’s B-25 (40-2344) began heading for the bow ramp.

The process took about one hour, and all had proceeded smoothly until the last. At 0919, Lt. William G. Farrow’s plane (40-2268) was about to take off when Sea1c Robert W. Wall, one of Hornet’s plank owners, buffeted by a gust of wind across the wet flight deck, slipped and fell toward the invisible arc of a whirling propeller blade that struck his left arm at the shoulder, necessitating amputation.

After taking off, each B-25 circled to the right and then overflew the carrier to align the axis with the plane’s drift sight. “This, through the use of the airplane compass and directional gyro permitted the establishment of one accurate navigational course,” Doolittle later explained, “and enabled us to swing off on to the proper course for Tokyo.” Their approach thus facilitated, Doolittle’s B-25s bombed targets in Tokyo, Yokosuka, Yokohama, Kobe, and Nagoya; one B-25’s ordnance damaged the small carrier Ryūhō (being converted from the submarine depot ship Taigei) at Yokosuka, the raid inflicting damage that, as Doolittle later wrote, “far exceeded our most optimistic expectations.”

Of the 16 B-25s launched, however, 15 all crashed in occupied China or on its coastline, the crews struggling ashore in the surf or bailing out into a dark void. In searching for the raiders, the Japanese carried out brutal reprisals against the Chinese populace in Chekiang province. One B-25, however, reached Soviet territory, landing at Vladivostok where it and its crew were interned by the Russians.

SBDs from VB-3 and VB-6, and F4Fs from VF-6 from Enterprise, meanwhile, wreaked havoc on the Japanese patrol vessels encountered near TF 16, damaging the armed merchant cruiser Awata Maru (depot ship for one of the guardboat squadrons) and guardboats Chokyu Maru, No.1 Iwate Maru, No.2 Asami Maru, Kaijin Maru, No.3 Chinyo Maru, Eikichi Maru, Kowa Maru, and No.26 Nanshin Maru. No.23 Nitto Maru and Nagato Maru, also damaged by SBDs and F4Fs from Enterprise, were sunk by Nashville’s gunfire; Japanese antiaircraft fire downed one of the Enterprise SBDs, but Nashville rescued the crew intact and unhurt. The next day, as Halsey’s task force put more distance between it and the enemy, gunfire from the light cruiser Kiso scuttled the irreparable No.26 Nanshin Maru, damaged by Enterprise planes the day before, while No.1 Iwate Maru sank as the result of the pounding inflicted by Enterprise planes on 18 April, the submarine I-74 rescuing her crew, transferring them to Kiso on 22 April.

While the material damage inflicted by Doolittle’s raiders proved small, and the early-warning line would be restored by an infusion of vessels to replace the guardboats lost, the effect of the air raid on the Japanese capital itself proved enormous. Adm. Yamamoto Isoroku’s fear of a U.S. carrier strike against the homeland, deemed “unreasonable” by the Naval General Staff, had occurred unimpeded. The Halsey-Doolittle Raid dissolved the “residual doubts” harbored within that planning body whether or not a thrust against the U.S. advanced naval base at Midway, an important element in Yamamoto’s plan to draw out the hitherto unengaged U.S. carriers, should be attempted. The Japanese Army, previously reluctant about the enterprise, went along with the Imperial Navy’s plan. Up to that point, the U.S. Navy’s carriers had operated in waters of their own choosing, from the Marshalls and Gilberts to New Guinea, uncontested by the Japanese, whose frustration increased correspondingly with their inability to engage the Americans.

Standing in to Pearl Harbor on 25 April 1942, Hornet moored in Berth F-9 off NAS Pearl Harbor, and fueled from Sabine (AO-25) the following day. The carrier remained at Pearl until the morning of the 30th, when she sailed as part of TF-16, in company with Enterprise, three heavy cruisers, seven destroyers and two oilers, their mission, as put succinctly in Hornet’s War Diary: “To halt Japanese advance in South Pacific and institute offensive action.” While Enterprise and Hornet did not encounter the enemy during their voyage into the South Pacific, they did, by their presence, cause alarm to the Japanese Navy, and hamper their operations in that theater. The Battle of the Coral Sea, fought between 4 and 7 May, the carriers Yorktown and Lexington (CV-2), under Rear Adm. Frank Jack Fletcher, had defeated their Japanese counterparts in the first battle where neither side engaged the other except with aircraft. Although Yorktown had suffered damage and Lexington had been scuttled after gasoline explosions rendered damage control impossible, their pilots and aircrew had sunk the small carrier Shōhō, badly damaged Shōkaku and rendered Zuikaku’s air unit unfit to fight – all three had been included in plans being developed to draw the U.S. carriers into battle over Midway.

Adm. Chester W. Nimitz, Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet, confronted a “most serious” situation after the Battle of the Coral Sea, and summoned Rear Adm. Fletcher and TF-17 back to Pearl in an expedited fashion; he also ordered TF-16 home from the South Pacific, its commander, however, Vice Adm. Halsey, suffering from shingles. When Hornet arrived back at Pearl Harbor on 26 May 1942, Capt. Charles P. Mason reported for duty, slated to relieve Mitscher as the carrier’s commanding officer.

Besides pulling back his carrier strength (Saratoga was on the west coast, ready to head west after having had torpedo damage repaired), Nimitz gave Midway “all the strengthening it could take,” reinforcing the Marine Aircraft Group, adding long-ranged Army bombers and Navy patrol planes, improving ground defenses and deploying submarines to cover the northern and western approaches.

After TF-16 returned to Pearl on 26 May 1942, the reins of command soon passed, at Halsey’s suggestion, to Rear Adm. Raymond A. Spruance, who had commanded the cruisers that had operated with Enterprise since hostilities descended upon the Pacific back in early December 1941. Yorktown arrived from the southwest Pacific on 27 May and entered dry dock the next day for repairs.

At 1133 on 28 May 1942, Hornet and Enterprise, with their screens of cruisers and destroyers, cleared Pearl “to prevent enemy attack and occupation of Midway.” TF-16 – two carriers, five heavy cruisers, one light cruiser, and 12 destroyers strong – set course for a point northeast of Midway. Hornet recovered her air group, that had been based at Ewa Mooring Mast Field, the USMC air installation on Oahu, and later proceeded past the island of Kauai. Over the next few days, Hornet conducted exercises and launched and recovered intermediate and inner air patrols, while her torpedo squadron, VT-8, drew a simple routine: “no school or unnecessary work” while her pilots and aircrew checked gear and planes daily. Sadly, on 29 May, the air group lost Ens. R. D. Milliman, A-V(N) and RM3c T. R. Pleto, when their SBD-3 (BuNo 4664) crashed, cause undetermined, at 0810.

On 31 May 1942, Capt. Mitscher executed the oath of office and accepted the rank of rear admiral in accordance with a “Bureau of Personnel dispatch dated May 30, 1942.” His slated relief, Capt. Mason, jovially asked Mitscher to remember that Hornet was really his (Mason’s) and to take good care of her!

On 4 June 1942, what history would record as the Battle of Midway opened during the mid watch, as PBYs from the atoll attacked the Occupation Force northwest of Midway; one of the Catalinas (VP-24) torpedoed the fleet tanker Akebono Maru. Other Catalinas set out before dawn, and one, at 0545, reported “many planes heading Midway” at a distance of 150 miles. Soon thereafter, another PBY sighted what appeared to be two enemy carriers and many other ships on the same bearing, 160 miles from Midway and closing the atoll at 25 knots.

That morning, Japanese carrier bombers (Aichi D3A1 Type 99) and attack planes (Nakajima B5N2 Type 97), supported by fighters (Mitsubishi A6M2 Type 00), from the carriers Akagi (flagship of Vice Adm. Nagumo Chūichi), Kaga, Sōryū, and Hiryū (four of the six that had launched the attack on Pearl Harbor) bombed installations on Midway’s two islands, Sand and Eastern. Although the defending USMC Brewster F2A-3 Buffalos and Grumman F4F-3 Wildcats of VMF-221 suffered disastrous losses, the Japanese had inflicted comparatively slight damage to facilities on Midway, necessitating a second strike.

Midway had launched a strike force of its own shortly before the enemy struck, and those planes, ranging from USMC Douglas SBD-2 Dauntlesses and Vought SB2U-3 Vindicators to USAAF Marauders rigged to carry torpedoes, and the detachment of six Grumman TBF-1 Avengers from Hornet’s VT-8 (Lt. Langdon K. Fieberling), met near annihilation at the hands of Japanese carrier fighters and antiaircraft fire. USAAF Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses likewise bombed the Japanese carrier force without success.

Hornet’s air group, however, encountered ill fortune from the start. Although Cmdr. Stanhope C. Ring, the “Sea Hag” (CHAG standing for Commander Hornet Air Group) stood senior to the group commanders in Enterpriseand Yorktown, he was the least seasoned, having had no combat experience whatsoever. The strike under his command consisted of 10 fighters, 35 SBDs and 14 TBDs. The fighters (Lt. Cmdr. Samuel G. Mitchell) and dive bombers VS-8, under Lt. Cmdr. Walter F. Rodee, and VB-8, under Lt. Cmdr. Robert R. Johnson, became separated and Enterprise’s fighter escort (VF-6) mistakenly attached itself to Hornet’s VT-8.

The first squadron to locate the Japanese, Torpedo Eight attacked without hesitation, and one by one, the squadron’s Devastators splashed into the unyielding ocean, shot down by fighters or antiaircraft fire; only one of Lt. Cmdr. John C. Waldron’s pilots survived, and none of the 15 radio-gunners. Only Ens. George H. Gay, Jr., A-V(N), escaped death that morning, being ultimately rescued by a Catalina. The next torpedo squadron, VT-6, like VT-8 separated from the rest of the group, escaped total annihilation but, again like Torpedo Eight, scored no hits.

Torpedo Three, from Yorktown, arrived soon thereafter and the Yorktown Air Group attacked. Bombing Three, despite having lost some ordnance en route due to faulty electric arming switches, with a small Fighting Three escort, reached the Japanese striking force simultaneously with Enterprise’s Air Group Commander and two intact squadrons: VB-6 and VS-6. Within a few minutes, SBDs from Enterprise pushed over and bombed and sank Kaga and bombed Vice Adm. Nagumo Chūichi’s flagship Akagi. SBDs from Yorktown (VB-3) bombed and sank Sōryū. Submarine Nautilus (SS-168) entered the fray and torpedoed Kaga but her “fish” failed to detonate.

As if Hornet’s air group performance had been disappointing enough, tragedy stalked the ship when an F4F-4 from Yorktown’s Fighting Three, piloted by Ens. Daniel Sheedy, A-V(N), wounded in action, made a rough landing, slewing to starboard on the flight deck. The impact of the descent caused his machine guns to rake the after part of Hornet’s island, killing five men and wounding 20. Among those killed was 29-year old Lt. Royal R. Ingersoll, son of Adm. Royal Ingersoll, the Commander in Chief, Atlantic Fleet.

The one carrier that escaped destruction that morning, Hiryū, launched dive bombers that bombed and temporarily disabled Yorktown, forcing Rear Adm. Fletcher to transfer his flag to heavy cruiser Astoria (CA-34) and turn over tactical command to Rear Adm. Spruance. Later that day, before SBDs from Enterprise (VS-6, joined by VB-3 that had been unable to operate from the immobilized Yorktown) could inflict mortal damage upon Hiryū, though, the Japanese carrier launched a second strike, with what remaining torpedo planes she could put into the air, that stopped Yorktown a second time and forced her abandonment.

Ultimately, the destruction of his carrier force compelled Adm. Yamamoto to abandon Midway invasion plans, and the Japanese Fleet retired westward. During the day, however, Japanese destroyer Arashi picked up a TBD pilot from VT-3; Makigumo an SBD crew, pilot and radio-gunner, from VS-6. The disaster witnessed by the Japanese destroyermen prompted them to show no mercy toward helpless prisoners-of-war. After interrogation, all three Americans were subsequently murdered – easily a fate that could have befallen Ens. Gay of Torpedo Eight had he been plucked out of the sea by the Japanese.

The Battle of Midway continued on 5 June 1942, as TF 16 (Rear Adm. Spruance) pursued the Japanese fleet, shorn of its central core of carriers, westward, while efforts proceeded to try and salvage the crippled Yorktown, which stubbornly remained afloat. Motor torpedo boats from Midway failed to locate “burning Japanese carrier” reported by Midway-based planes. Japanese destroyers, after taking on board the last survivors of those ships, destroyers Nowaki, Arashi, and Hagikaze scuttled Akagi, while Kazegumo and Yugumo scuttled Hiryū, although men from her engineering force had been left behind, given up as lost, and eventually made it topside to abandon ship; 35 were eventually rescued by the seaplane tender Ballard (AVD-10).

Retiring from Midway, the Japanese heavy cruisers Mogami and Mikuma, their gunfire support duties in an invasion effectively cancelled by the destruction of Nagumo’s carriers, were thrown into confusion when they tried to avoid the submarine Tambor (SS-198) and were thus unwitting participants in one of the closing elements of the Battle of Midway. Planes from Enterprise and Hornet attacked, SBDs bombing and sinking Mikuma; Hornet’s SBDs scored five hits on Mogami and near-missed and damaged destroyers Asashio and Arashio. At Rear Adm. Spruance’s expressed orders (because of the destruction of VT-3, VT-6, and VT-8 on 4 June), the TBDs from VT-6 that accompanied the strike did not attack because of the antiaircraft fire from the Japanese ships. After recovering planes, TF-16 changed course to eastward to refuel and broke contact with the enemy.

Meanwhile, the Japanese submarine I-168 located Yorktown, being towed by the tug [ex-minesweeper] Vireo (AT-144) and screened by destroyers. Aided by poor listening conditions, I-168 launched a spread of torpedoes that inflicted further damage to Yorktown as well as sinking Hammann (DD-412) while she lay tied-up alongside providing support for the salvors. Screening destroyers depth-charged I-168, but the Japanese I-boat, though damaged, escaped destruction. Yorktown rolled over and sank the following morning [7 June].

Hornet maintained six-plane inner air and intermediate air patrols on 8 June 1942, as all ships in TF-16 fueled from Cimarron beneath overcast skies and unsettled, sometimes squally, weather. On the 9th, the task force encountered heavy fog toward the end of the mid watch as it set course to rendezvous with Saratoga. Spruance’s ships encountered foggy weather and light rain, the poor visibility conditions deemed too poor for air operations.

Eventually, on 11 June 1942, Hornet received 10 Grumman TBF-1 Avengers from Saratoga, assigned to VT-8, and nine SBDs to bring VS-8 and VB-8 up to strength (0648-0710), upon completion of which the task force headed north “for possible participation in [the] Aleutian campaign.” CinCPac, however, directed Spruance to return to Pearl, his task force reaching its destination on the afternoon of 13 June, Hornet mooring at Berth F-9, Ford Island.

At 0820 on 15 June 1942, Capt. Mason relieved Rear Adm. Mitscher as commanding officer, and the latter assumed command of TF-17, breaking his flag in Hornet. As the month of June continued, the carrier shifted to berth B-17 in the Pearl Harbor Navy Yard where workers installed the CXAM radar “bedspring” that had been removed from battleship California (BB-44), damaged during the Pearl Harbor attack, the SC-1 radar being re-located to the mainmast, removed her catapults, “and other miscellaneous work” (20-28 June), returning to moor at F-9. Two days later, on 30 June, Rear Adm. Aubrey W. Fitch relieved Rear Adm. Mitscher as Commander TF-17, Mitscher becoming Commander Patrol Wing 2.

Hornet returned to the yard on 3 July 1942, mooring in Berth B-12, where she received a fifth 1.1-inch mount at the bow, replacing the two 20-millimeter mounts. Yard hands performed additional items of work over ensuing days, the carrier shifting to F-2 off Ford Island on 8 July once all repairs and alterations had been accomplished.

Hornet sailed on 13 July 1942 to conduct a training exercise in the Hawaiian Operating Area, in company with Northampton, Pensacola (CA-24), San Francisco (CA-38) and San Diego (CL-53) and six destroyers. All ships fired antiaircraft practices, night and day surface gunnery practices, and bombardment exercises – conducted by the ships and by Hornet’s planes. With 35 U.S. Army observers on board as observers, the carrier went through her paces, and also conducted qualifications for USMC pilots.

Returning to Pearl an hour before the end of the afternoon watch on 16 July 1942, Hornet moored off Ford Island at F-2. Her war diarist noted that the recently concluded evolutions had been “a very successful training period for all types.” The carrier returned to sea for another stint of intensive exercises – task force maneuvers, tactical evolutions with the battleships of TF-1, more night and day gunnery practices, and additional USMC pilot qualifications.

Hornet, loaded, fueled, and provisioned, cleared Pearl Harbor at 1024 on 17 August 1942 as flagship for TF-17, and wearing the flag of Rear Adm. George D. Murray, who had previously commanded Enterprise. The other ships bound for the South Pacific included Hornet’s old consort Northampton, Pensacola, San Diego, the destroyers Morris (DD-417), Mustin (DD-413) O’Brien (DD-415), Hughes (DD-410), and Russell (DD-414) and the oiler Guadalupe (AO-32). Hornet maintained inner air patrols as well as “A.M. and P.M. searches,” weather permitting. As needed, the heavy cruisers operated their floatplanes to spell the carrier pilots on inner air patrols. Five days into the voyage, Guadalupe fueled four of the destroyers, while the cruisers fueled one destroyer each.

On the night of 23 August 1942 (Zone +11 Time), Hornet intercepted radio transmissions on both the CAP and attack frequencies that indicated that Enterprise and Saratoga, with their respective supporting ships “were engaged in the Solomons.” As Hornet’s war diarist wrote subsequently: “Later information proved this to be correct. Japanese carrier and transport forces apparently attempted to recapture Guadalcanal and Tulagi, and were driven off. Casualties and damage on either side not definitely known on board this ship at present, but all indications are of a definite victory for our forces.” Indeed, the radio messages told of the Battle of the Eastern Solomons, with TF 61 (Vice Adm. Frank Jack Fletcher), supported by USMC and USAAF planes from Henderson Field, indeed turning back a major enemy thrust to recover Guadalcanal and Tulagi on the 24th.

While Enterprise had suffered damage from carrier bombers from Shōkaku (and a near-miss contributed by an Aichi from Zuikaku), North Carolina escaped the attentions of the planes from those two carriers; Graysonsuffered damage from strafing and a near-miss. SBDs from VB-3 and TBFs from VT-8, flying from Saratoga, sank the small carrier Ryūjō after her planes had bombed U.S. positions on Lunga Point, VB-3 SBDs damaged the seaplane carrier Chitose. On 25 August 1942, in the wake of the carrier encounter of the previous day, USMC SBDs from VMSB-232, operating from Henderson Field, damaged light cruiser Jintsu north of Malaita Island, Solomons, forcing Rear Adm. Tanaka Raizo, the commander of the Guadalcanal-bound reinforcement convoy, to transfer his flag to the destroyer Kagero, and damaged the troop transport Boston Maru, while an SBD from VB-6 bombed and damaged the armed merchant cruiser Kinryu Maru north of Guadalcanal. Later, USAAF B-17s, flying from Espiritu Santo, sank the destroyer Mutsuki off Santa Isabel as she stood by the sinking Kinryu Maru.

Once TF-17 crossed the equator, Commander South Pacific Force (ComSoPac) (Vice Adm. Robert L. Ghormley) ordered it to proceed to an area west of Guadalcanal and prepare for “offensive operations further to [the] westward.” Guadalupe fueled the task force on 25 August 1942, completing the replenishment by moonlight at 2200, then, with Hughes as escort, was detached.

At noon the following day [26 August 1942], Hornet’s radar picked up an unidentified plane bearing 220° to 320° at a distance that varied from 22 to 50 miles away, in the general vicinity of where her air group was maneuvering, preparing to make a simulated attack on TF-17. Consequently, Hornet turned into the wind and launched two Wildcats at 1250 to investigate, to search in the general direction of the contact, but the flights yielded nothing. Upon reflection, the contact being picked up 690 miles, bearing 100° from Ndeni raised the possibility that the unidentified aircraft was a Japanese flying boat or a U.S. plane operating from Fiji “or in transit to Pearl.”

ComSoPac ordered TF-17 to “proceed to a prospective rendezvous” with TF-61 in the waters to the eastward of the southern Solomon Islands on 27 August 1942, “prepared for offensive operations to the westward.” Consequently, Hornet and her consorts set course for that area at a speed of advance 16 knots. On that day and the next, Mustin and Russell each transferred a man to the carrier for appendectomies, the destroyers coming alongside and transferring the sick sailors by stretcher, Hornet’s war diarist noting “making a total of three such transfers on this cruise.”

On 29 August 1942, Hornet sighted TF-61 approaching – a goodly company of warships. TF-11, Vice Adm. Fletcher’s flag in Saratoga, consisted of that carrier, the battleship North Carolina, heavy cruiser Minneapolis (CA-36), the Australian heavy cruiser HMAS Australia and light cruiser HMAS Hobart, and several destroyers. In addition, TF-18 consisted of Wasp (CV-7), wearing Rear Adm. Leigh Noyes’ flag, heavy cruisers Salt Lake City and Portland (CA-33) and several destroyers. Hornet and her attendants thus became TG 61.2, with Salt Lake Citybeing assigned to their number, and the force changed its base course frequently, to maintain position in the area, “inasmuch as the major objective of the force,” the carrier’s diarist wrote, “is to guard the lines of communication to Guadalcanal and Tulagi.” As if unidentified aircraft such as that detected on 26 August were not enough, B-17s and PBYs operating out of Espiritu Santo and Ndeni posed their own problems – not equipped with IFF (identification friend or foe) prompted frequent violations of radio silence to vector fighters to intercept the Flying Fortresses or Catalinas.

Hornet transferred officer passengers to Anderson that came alongside to receive them on 30 August 1942, five bound for Wasp and one for Salt Lake City. At sunset that day, the light cruiser Phoenix (CL-46) replaced Salt Lake City in TG 61.2, with Salt Lake City going with Wasp as that carrier’s task group was detached to proceed independently to Noumea, New Caledonia, to fuel and take on provisions. Destroyers Bagley (DD-386) and Patterson (DD-392) joined Hornet’s company.

At 0741 the following day [31 August 1942], Hornet, steaming on a base course of 040°, received a garbled report over the TBS [low-frequency voice radio] circuit: “050----carrier----” Had an enemy carrier been sighted? A second transmission, however, 30 seconds later brutally clarified matters: a torpedo was approaching Saratoga from 050°. Whether the bearing in the garbled message was true or relative proved academic, for the torpedo, fired by the Japanese submarine I-26, punched into Saratoga’s starboard side at 0746. Hornet’s war diarist noted that “the column of water rising to a height slightly higher than the height of her mast.”

Hornet and her consorts immediately turned 090° and steamed away at 20 knots while Saratoga slowed to a stop, going dead in the water. Hornet turned into the wind at 0801 and began launching additional Wildcats and an antisubmarine patrol. Nine minutes later, her lookouts spotted a surfaced torpedo 4,000 yards on the starboard bow, and the ship, at that point between 10,000 and 12,000 yards from the crippled Saratoga, turned to port to avoid it, still making 20 knots. It turned out that the torpedo had most likely come to the end of its run, for those who saw it did so for only a short time before it disappeared. Two minutes later (0812), Russell, 4,000 yards off Hornet’s starboard bow, picked up a sound contact and dropped an “embarrassing barrage” of two depth charges while the task group turned away on course 320°T, Russell remaining on the scene to develop the contact, without result.

Hornet turned into the wind again at 0813 and completed the launching evolution, then remained at general quarters until a little over a half an hour into the afternoon watch (1231), operating in Saratoga’s general vicinity, with Minneapolis preparing to tow the damaged carrier. North Carolina, meanwhile, joined the Hornet task group. A little less than an hour later, by 1330, Saratoga appeared to be steaming under her own power, launching 29 planes that set course for Espiritu Santo. Hornet provided air cover, as did two PBYs operating from the small seaplane tender Mackinac (AVP-13). With Enterprise requiring repairs after having been damaged in the Battle of the Eastern Solomons, and Saratoga damaged, only Hornet and Wasp remained fully operational.

Shortly before sunset the same day [31 August 1942], Rear Adm. Murray received orders from Vice Adm. Fletcher to proceed independently with TG 61.2, to remain in the area, and fuel on 2 September. Phoenix, Bagley and Patterson were detached to proceed and report to Commander Task Force 44 for duty, then to sail for Brisbane, Australia, in company with HMAS Australia and HMAS Hobart. Monssen, left at the scene of the earlier action to keep the submarine down until sunset, carried out her mission but, as Hornet’s chronicler noted, “no indication received by this ship that the submarine had received any damage from our forces.” The day continued to its end, with no further contact with the enemy and the radar picking up occasional unidentified aircraft that turned out to be, upon investigation, “friendly…with ineffective identification equipment…”

Having refueled well to the east of Espiritu Santo, TF-17 proceeded between the New Hebrides and the Santa Cruz Islands on 4 September 1942, south of where Saratoga had been torpedoed less than a week before. The orders given Rear Adm. Murray were simply to operate in support of the Guadalcanal campaign, generally south of 12° south latitude “to destroy enemy surface forces wherever located,” with the priority, in descending order, to carriers, transports, battleships, destroyers, and other shipping.

While submarines did not appear on the priority list, the threat they posed made them targets in their own right. On 6 September 1942, Hornet launched a patrol of TBF-1s from Torpedo Six at 1425. Ens. Eppler, first off the deck, made a wide sweep and saw an explosion from his vantage point just outboard of his left wing. He turned his Avenger in that direction and armed his depth charge, then saw the wake of a torpedo. Another explosion occurred astern of the torpedo, causing it to broach then do a nose dive, when it exploded – it had been on course toward the carrier’s stern. Ens. John Cresto, A-V(N), launched on that flight, sighted a torpedo wake running parallel to the ship on her starboard quarter, then saw what appeared to be an explosion where the torpedo had originated. Following the wake, he dropped a Mk. 17 depth charge where he thought the submarine was. Later, at about 1725, while returning from a 150-mile search flight, VB-8’s Lt. John J. Lynch and Ens. William D. Carter, A-V(N), spotted a surfaced submarine three miles away off their port bow moving at six or seven knots. The boat sighted them and began crash diving. Lynch dropped his depth charge, then Carter attacked and dropped his, the two explosions occurring close enough “to join together and form one circle in [the] water…” The two Bombing Eight pilots circled for ten minutes but could see no conclusive evidence they had sunk the boat. Nevertheless, both Capt. Mason and Rear Adm. Murray believed that on the evidence presented by the pilots in their reports, that “the submarine attacked by Lieutenant Lynch and Ensign Carter was sunk as a direct result of their combined depth bombing.”

Anderson and Russell, however, left behind to keep the submarine down, encountered I-11 (Cmdr. Shichiji Tsuneo commanding). Russell attacked the I-boat, damaging her to the extent that she plunged to 490 feet before coming back to an even keel. The depth charges caused leaks, disabled the sound gear for a time, and filled the forward compartments with chlorine gas. The boat survives the attacks and eventually made her way back to Truk. Hornet had had a close call.

Operations in those dangerous waters, however, continued. On 15 September 1942, Wasp was serving as the duty carrier while Hornet steamed in company with North Carolina and her screen, some five to six miles to the northeast but conforming to Wasp’s movements, escorting a troop convoy carrying the 7th Marines to Guadalcanal. At 1442, Wasp had just completed recovering planes, and her flight deck crew began re-spotting the deck for the next patrol, when at 1444, however, lookouts spotted three torpedoes heading for her. In swift succession, the “fish” slammed into the carrier, rupturing gasoline lines and touching off hellish conflagrations; within minutes, the ship shuddered under the impact of massive internal explosions. Despite the heroic actions of her men, Wasp was doomed. Within a short time, torpedoes, fired by the same submarine, I-19 (Lt. Cmdr. Kinashi Takakazu, who had ironically stalked Wasp on 26 August), hit North Carolina and O’Brien. Wasp’s loss rendered Hornet the only operable U.S. fleet carrier in the theater.

Hornet continued operating around Guadalcanal (16-27 September 1942) in the wake of the loss of Wasp, her encounters with the enemy limited to VF-72’s shooting down Japanese “snoopers.” The carrier proceeded to Noumea, New Caledonia, where 32 Wildcats and ten Dauntlesses based ashore at Tontouta airfield. She flew 12 SBDs off to Efate. When TF 17 sortied at noon on 2 October, it set course for what was reported to be a large concentration of Japanese shipping in the area of Buin, Faisi, and Tonolei – essentially the staging area for the “Tokyo Express.” Hornet recovered the Tontouta-based part of her group but weather conditions at Efate prevented the planes there from taking off. Unable to recover that element, the air department brought down six spare SBDs from the overhead onto the hangar deck and 2 Avengers.

Detaching the destroyers at 1000 on 4 October 1942, Hornet began the high-speed run to the target, in company with Northampton, Pensacola, San Diego, and Juneau (CL-52), the two light cruisers, with their heavy antiaircraft batteries, deployed on each bow with the heavy cruisers on each quarter until sunset, at which point the ships formed a column with Juneau and San Diego in the lead, and with Pensacola and Northampton astern. Hornetlaunched a combat air patrol the next morning, then launched the first attack group that took off without incident but encountered a very heavy weather front on the way to Tonolei, forcing the group to break up “into several groups of varied size and composition…” The attack groups then carried out their attacks on the objective within 10 or 15 minutes of sunrise “in very bad weather, which amounted to semi-darkness.” Hornet’s planes all returned having incurred only one bullet hole, and pounded installations ashore and damaged destroyers Minegumo and Murasame, and near-missing the seaplane tenders Sanuki Maru and Sanyo Maru. Hornet had also forced the temporary postponement of a planned re-supply run to Guadalcanal by the seaplane carrier Nisshin. A little less than a fortnight later, on 16 October, TF 17 struck again, pounding Japanese troop concentrations on Guadalcanal and the seaplane base at Rekata Bay, VT-6 Avengers bombed the transport Azumasan Maru that had suffered severe damage the previous day.

In view of an impending Japanese push into the southern Solomons, Adm. Halsey, who had relieved Ghormley as ComSoPac, ordered TF-61, composed of TF-16 (Rear Adm. Thomas C. Kinkaid), with the hurriedly repaired Enterprise, and TF-17 (Rear Adm. Murray) with Hornet, to “proceed around the Santa Cruz Islands to the north, thence proceed southwesterly and east of San Cristobal to area in Coral Sea and be in position to intercept enemy forces approaching the Guadalcanal-Tulagi area…” The ensuing Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands found the Americans engaging a numerically superior Japanese force (Vice Adm. Nagumo).

Although the Japanese achieved a tactical victory, the failure of their simultaneous land offensive on Guadalcanal meant that they could not exploit it to its fullest. The dwindling number of Japanese carrier planes could not eliminate Henderson Field, while fuel shortages compelled the Combined Fleet to retire on Truk. The Americans controlled the skies above the sea routes to Guadalcanal, while the marines held their positions on Guadalcanal.

The victory, however, did not come cheaply in the fourth major carrier battle of 1942, for Enterprise was damaged by planes from Junyo and Shōkaku; Hornet was damaged by planes from Junyo, Shōkaku, and Zuikaku;battleship South Dakota (BB-57) and light cruiser San Juan (CL-54) were damaged by planes from Junyo; Smith(DD-378) was damaged by a crashing carrier attack plane; during the operation of fighting Hornet’s fires and taking off her survivors, Hughes suffered damage alongside the doomed carrier (as well as by friendly fire earlier in the action); Porter (DD-356), accidentally torpedoed by a battle-damaged and ditched TBF from VT-10, deemed beyond salvage, was scuttled by Shaw (DD-373). SBDs (VS-10) from Enterprise damaged Zuiho, however, while SBDs (VB-8, VS-8) from Hornet damaged Shōkaku and the destroyer Terutsuki; Hornet TBFs (VT-6) damaged the heavy cruiser Chikuma.

The attempt to scuttle the irreparably damaged Hornet, by gunfire and torpedoes from destroyers Mustin and Anderson failed. As Japanese ships closed in, Mustin and Anderson set course away from the burning carrier that refused to sink. Abandoned, and already damaged by bombs and torpedoes, and the attempted scuttling by torpedoes and gunfire, Hornet was finally sunk by the Japanese destroyers Akigumo and Makigumo.

Hornet's ship's company had suffered six officers and 70 men killed in action, as well as 15 marines from the ship's Marine Detachment. Of the Hornet Air Group, VF-72 lost 9 men, VB-8 11, VS-8 5, and VT-6 2; casualties in the air totalled six officers lost in VF-72, 1 officer and 1 enlisted man in VB-8, and one officer and two men lost from VT-6.

Hornet was stricken from the Naval Register on 13 January 1943.

Hornet received four battle stars for her World War II service, for the Halsey-Doolittle Raid (18 April 1942), the Battle of Midway (4-7 June 1942), the Buin-Faisi-Tonolei Raid (5 October 1942) and the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands (26 October 1942).

| Commanding Officers | Dates of Command |

| Capt. Marc A. Mitscher | 20 October 1941–15 June 1942 |

| Capt. Charles P. Mason | 15 June 1942–26 October 1942 |

Robert J. Cressman

18 April 2017