Nautilus III (SS-168)

1930–1945

Named for a tropical mollusk.

III

(SS-168: displacement 2,730 (surface); 3,960 (submerged); length 371'; beam 33'3"; draft 15'9"; speed 17 knots (surface), 8 knots (submerged); complement 88; armament 2 6-inch, 2 .30 caliber machine guns, 10 21-inch torpedo tubes; class Narwhal)

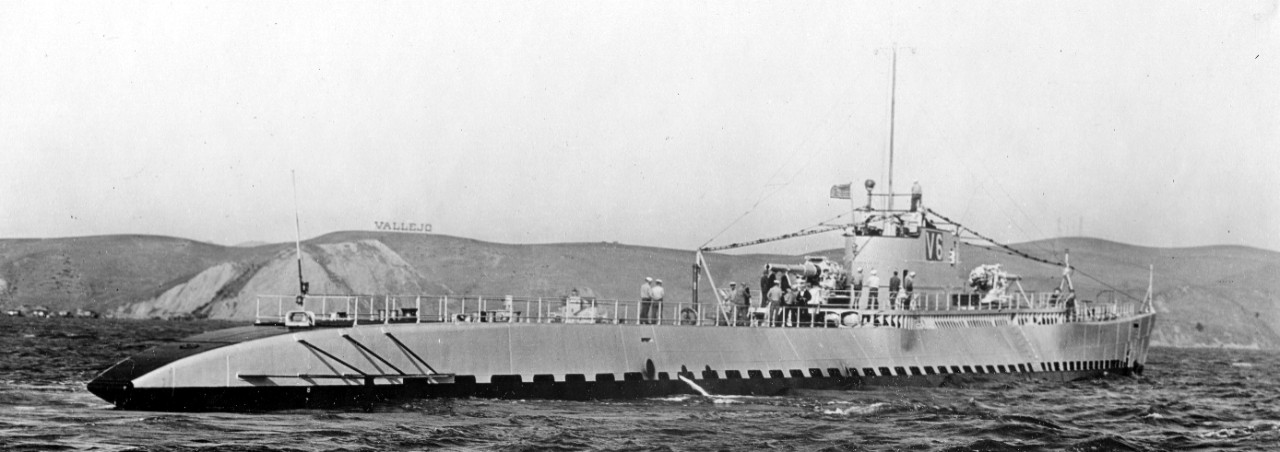

V-6 (SC-2) was laid down on 2 August 1927 at Vallejo, Calif., by the Mare Island Navy Yard; launched on 15 March 1930 and sponsored by Miss Jean Keesling, the daughter of the prominent San Francisco attorney Francis B. Keesling, a booster of the USN.

Commissioned on 1 July 1930, Lt. Cmdr. Thomas J. Doyle Jr., in command, V-6 represented the pride of the early 1930s U.S. submarine fleet. A newspaper article published about her in 1930, complete with an artistic diagram, described V-6 as “a uniquely designed, submersible cruiser, built for size, speed, and offensive power.”

From the date of her commissioning through January 1931, V-6 operated out of Mare Island, occasionally making the short trip to San Francisco Bay and vice versa. Her first extensive cruise began on 14 January 1931, when she stood out from San Francisco Bay for Port Susan, Wash., where she arrived five days later on the 19th and anchored in 60 fathoms. She got underway again on the 23rd and shaped a course for San Diego, Calif.

V-6 arrived at her destination on 29 January 1931, and moored in Berth 60. From 29 January to 8 February, she operated from that port conducting submergence tests and torpedo exercises. The boat then set out for Fleet Problem XII on the 16th, headed for Balboa, Canal Zone (C.Z.), to join other components of the U.S. Fleet participating in exercises in that area. While on that voyage, on the 19th, she was formally renamed Nautilus. The submarine arrived in Balboa Harbor on the 27th and moored alongside the submarine tender Holland (AS-3). In the month that followed, she conducted exercises between Balboa, Panamá Roads, and the Perlas Islands.

With her trials completed in late March 1931, Nautilus got underway on the 23rd and began transiting the Panama Canal en route to Portsmouth, N.H. The boat arrived at Portsmouth Navy Yard on 1 April and moored starboard side to the Flat Iron Pier. During her time in the area, she travelled to New London, Conn., and demonstrated her exceptional diving capabilities, conducting a special submergence test off the Isles of Shoals, a group of small islands and tidal ledges approximately six miles off the coastal borders of the U.S. states of Maine and New Hampshire. In the course of those tests, she dove to the previously unmatched depth of 56 fathoms.

At the conclusion of her submergence tests, on 7 April 1931, Nautilus steamed to the New York Navy Yard, Brooklyn, N.Y., where she arrived on the 9th; and then only a few days later, on the 11th, got underway for Washington D.C., where she arrived on the 13th. Nautilus lay moored at the Washington Navy Yard for a couple of days and then shifted to Annapolis, Md., where she remained for the better part of a week. She stood out from Annapolis on the 24th and shaped a course for Coco Solo, C.Z. The boat arrived at her destination on the 29th and then spent several days engaged in local exercises.

On 4 May 1931, Nautilus weighed anchor from Coco Solo and then, after transiting the Panama Canal, shaped a course for San Diego. Following a ten-day voyage, the boat entered San Diego Harbor on 14 May and then shortly after anchoring began a month-long refit. Ready for sea again on 18 June, Nautilus, got underway as part of Submarine Division (SubDiv) 12, to conduct exercises. Two days later on the 20th, she anchored in berth 14 at San Francisco. The boat did not get underway again until 1 July, when she steamed out of San Francisco with Argonaut (SM-1) and the rest of SubDiv 12 and made her way to San Diego, arriving there on the 3rd.

During the next three months, Nautilus remained based at San Diego but made several excursions into local waters with her fellow submarines to conduct exercises. On 1 July 1931, Nautilus was re-designated SS-168. The boat steamed to the vicinity of Pyramid Cove, San Clemente Island, Calif., from 20-24 July, and then in August she went to Coronado, Calif., from 10-11 August. Following exercises off Coronado, Nautilus proceeded to San Francisco (19-31 August). Back in San Diego as of 1 September, she remained in port for the rest of the month. Accompanying SubDiv 12, Nautilus conducted local exercises on 1 and 13 October, but the boat remained largely inactive during most of November and December.

On 2 January 1932, Nautilus steamed to the Mare Island Navy Yard, and subsequently entered Dry Dock No. 1. Two months later on 7 March, she came off keel blocks and moored in Berth H. With her overhaul completed on 7 April, Nautilus steamed to San Francisco Bay, conducting trials en route, then moored starboard side to her sister ship Narwhal (SS-167) in Berth 62 at San Diego on 10 April. The following morning, Nautilus got underway for a brief exercise and then returned to San Diego on the 13th. On 18 April, the boat stood out to sea with SubDiv 12 and then for several days thereafter conducted tactical exercises with the battleship Pennsylvania (BB-38), as well as the carriers Langley (CV-1) and Saratoga (CV-3). With fleet maneuvers completed on the 24th, Nautilus moored at Pier 36 in San Francisco.

Returning to San Diego on 14 May 1932, Nautilus operated locally for the remainder of the year, participating in a Battle Force Tactical Exercise (2-4 June), as well as several SubDiv 12 exercises off Coronado (23-26 August, 15-16 November, and 12-14 December).

On 6 February 1933, Nautilus got underway for Fleet Problem XIV, which brought her to San Francisco (16-19 February) and eventually ended with her moored back at San Diego on 1 March. She stood out to sea for “Fleet Tactical Exercise B-2” in company with SubDiv 12 on 6 March, and returned to San Diego on the 14th.

Underway on 27 March 1933, Nautilus steamed in “Cruising Formation 2-C,” with Narwhal and Barracuda (SS-163) to “conduct an exercise with the U.S. Fleet.” The submarine detached for Coronado on 29 March, and then moored at San Diego in Berth 60 on the 31st. Other than local operations at Pyramid Cove, Nautilus spent most of the next several months at port. From 10 to 13 August, the boat transited to San Francisco, and then a few weeks later on the 31st, she steamed to Mare Island, arriving there the following day and mooring at Pier R-1. On 10 November, Nautilus entered Dry Dock No. 1, and lay on keel blocks for the rest of the year.

Clearing Mare Island on 17 January 1934, Nautilus steamed to San Francisco, mooring there in company with SubDiv 12 on the 20th. From 21 to 23 February the submarine participated in a Fleet Tactical Exercise in local waters and then on 9 April she got underway for Fleet Problem XV, which brought her to Coco Solo (25 April), Ponce, Puerto Rico (11 May), Coco Solo (15 May), Balboa (17 May) and then finally back to her homeport in San Diego (1 June).

In early June 1934, Nautilus made her way to San Francisco, and then on 9 July she got underway with SubDiv 12 for a cruise to Alaskan waters. She first voyaged to Tacoma, Wash. (9-13 July), then to Ketchikan, Territory of Alaska (T.A.) (19-22 Jul), from Ketchikan to Juneau, T.A. (22-30 July), Juneau to Valdez, T.A. (31 July-2 August), Valdez to Kodiak, T.A. (6-7 August), Kodiak to Dutch Harbor, T.A. (10 August) and finally, from Dutch Harbor to Pearl Harbor, Territory of Hawaii (T.H.) (16-25 August). Just a week after mooring at the Submarine Base at Pearl, Nautilus went into dry dock at the navy yard there.

On 8 September 1934, Nautilus stood out of Pearl in company with Narwhal, and shaped a course for San Diego, conducting a “factor SA of Annual Readiness for War Trial” en route. The submarine arrived in San Diego Harbor on 19 September and moored to buoy 70, with the rest of SubDiv 12. During October and November, Nautilus operated locally. From 5 to 8 December, she participated in “Battle Force Strategical and Tactical Exercises” that concluded with her moored at San Francisco. On 17 December, the boat got underway for Coronado, and then on the 19th steamed to San Diego.

Nautilus accompanied SubDiv 12 for “Fleet Exercises” between 14 and 16 January 1935, after which she returned to San Diego. The following month, on 11 February, Nautilus got underway for an exercise, but a few days into the operation, on the 13th, she broke away and joined Bass (SS-164), Barracuda, Dolphin (SS-169) and Narwhal, in order to search for any possible survivors of the rigid airship Macon (ZRS-5), Lt. Cmdr. Herbert V. Wylie in command. The airship had crashed on the 12th, after hitting a storm off the coast of Point Sur, Calif. Nautilus did not pick up any of the 81 survivors.

On 14 February 1935, the submarine moored at San Francisco and then transited to San Diego (23-24 February) where she remained for several months, a period punctuated by visits Pyramid Cove. Nautilus stood out of San Diego for Fleet Problem XVI on 29 April and a week later arrived at the Submarine Base at Pearl with Argonaut, mooring on 14 May. The following morning she continued her participation in the fleet exercise and steamed for Midway Atoll, located near the western end of the Hawaiian archipelago. During the remainder of her time participating in Fleet Problem XVI, Nautilus steamed back to Pearl on 25 May, and then eventually returned to San Diego on 5 June.

On 8 June 1935, Nautilus got underway for Mare Island, docking there on the 10th, and then on the 30th, entered Dry Dock No. 1. The submarine remained at Vallejo until 5 September, and then got underway for San Diego, mooring there on the 8th. Nautilus remained largely at anchor for the rest of the year, only participating in local exercises.

From 6 to 9 January 1936, Nautilus participated in a fleet tactical exercise and then moored at San Diego. In April, from the 13th to the 18th, she underwent repairs at Mare Island and then on the 25th got underway with Submarine Squadron (SubRon) 6, for Fleet Problem XVII. In the course of the fleet exercise she voyaged to Balboa (9 May), Bona Island, Republic of Panama (16 May), Balboa (22 May), Panama Bay (25 May), and then finally returned to San Diego (7 June). Just a few weeks after ending her participation in Fleet Problem XVII, Nautilus got underway for an annual Readiness War Trial exercise (30 June-2 July).

In company with SubRon 6, Nautilus got underway from San Diego on 6 July 1936, and steamed to Pearl Harbor, arriving at the Submarine Base there on 15 July. The submarine spent most of August refitting at Pearl and then for the next several months got underway for brief exercises in Hawaiian waters. On 31 November, Nautilus returned to San Diego with SubDiv 6, mooring in the harbor on 9 December. Only a few days later on the 13th, she transited to the Submarine Repair Base at Mare Island, and began a three-month overhaul.

On 12 March 1937, Nautilus stood out of Mare Island and returned to San Diego, stopping over at San Francisco on the way. The following month, on 16 April, Nautilus got underway with Dolphin, Pike (SS-173), Shark (SS-174) and Porpoise (SS-172) to participate in Fleet Problem XVIII. On 30 April, she arrived in the vicinity of Kaula Rock Light, Kaula Island, T.H., with other elements of the U.S. fleet. With her part in the exercise completed on 9 May, Nautilus anchored at Pearl. Eleven days later, she returned to San Diego, steaming from 19 to 28 May.

Once back in her home waters, Nautilus spent the rest of the year largely inactive at port, getting underway for only a few minor training exercises with SubRon 6, primarily in the vicinity of Pyramid Cove and Coronado. Between 4 and 9 December, she made her way to the Submarine Base at Mare Island and commenced another multi-month overhaul.

Upon the completion of those repairs and alterations, Nautilus was re-assigned to base at Pearl Harbor. On 1 February 1938, she stood out of Mare Island and nine days later arrived at the Submarine Base at Pearl, mooring to Pier 3. The submarine participated in Fleet Problem XIX from 22 March to 2 April, which took her to an operating area near La Perouse Pinnacle, French Frigate Shoals, in the Hawaiian chain. Upon returning to port, Nautilus began an extensive overhaul, where she rested on keel blocks at the Navy Yard for several months. On 15 July, she conducted post-repair trials off Oahu, T.H., and then the following day returned to her moorings. The trial run revealed some ongoing mechanical issues that ultimately kept the boat inactive for several months.

Now fully operational, Nautilus got underway on 3 November 1938 for trial runs, and then on 7 November, conducted a practice torpedo run. The submarine remained moored at Pearl for the next two months getting underway only for local exercises. Her activity picked up slightly on 27 January 1939, when she steamed out of port for a “War Trial,” that kept her at sea until 4 February. She moored at Pearl for the majority of February, March, and April, getting underway for local exercises. On 2 May, the boat steamed for French Frigate Shoals, anchoring there on the 3rd. Following brief exercises in the area, she returned to Pearl.

A few months later, Nautilus made a similar excursion to French Frigate Shoals (21-24 August 1939), but largely remained moored at port. This relative inactivity continued into the fall with Nautilus making short trips to various Hawaiian Islands. Beginning in January 1940, Nautilus underwent extensive repair work done alongside Ten Ten Dock, Pearl Harbor Navy Yard, whicht lasted into March. On 23 March, she put out to sea for post repair trials and returned to Pearl the following day. A few weeks later on 17 April, Nautilus got underway with Dolphin for Fleet Problem XXI. The exercise concluded on the 26th and the submarines returned to Pearl.

Steaming in local waters, Nautilus participated in “Modified Readiness for War Trials,” from 3 to 6 June 1940. The following month, on 14 July, she voyaged with the rest of Submarine Squadron 4, to Pago Pago, American Samoa, arriving there on the 17th, then eventually returned to Pearl on the 27th. The boat remained relatively inactive all of August but the following month, in September, she got underway for “Fleet Exercise 121” steaming with Argonaut and Dolphin from the 9th to the 17th. Moored at Pearl, Nautilus rarely got underway in the succeeding months, engaging in only a handful of local exercises. On 24 December, she entered Dry Dock No. 1 at the Pearl Harbor Navy Yard.

Months of extensive maintenance during the first part of 1941 resulted in Nautilus being ordered back the west coast to undergo modernization. Getting underway in July 1941, the submarine voyaged back to the Mare Island Navy Yard, where she received updated radio equipment, a modern engine, and one of a submariner’s dearest amenities, air-conditioning. She still lay at Mare Island on 7 December 1941, when the Japan onslaught engulfed the U.S. and its British and Dutch allies in the Pacific and Far East.

Nautilus departed San Francisco on 21 April 1942, and arrived at Pearl on the 28th. She left Pearl on 24 May and then set a course for Midway. She deployed as part of the Midway Task Group, which consisted of 25 submarines, charged with locating and attacking an Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) fleet believed to be preparing for an assault on U.S. forces at Midway. The advance information on the attack, which indicated either 4 or 5 June as the target date, was obtained as a result of the work of U.S. cryptographers who had partially broken Japan’s JN-25b code.

In the early morning of 4 June 1942, Nautilus, Lt. Cmdr. William H. Brockman, Jr., on his own initiative having his radiomen monitor the assigned frequency in advance of the time specified in his operations orders, intercepted a message from a patrolling PBY telling of a large formation of enemy planes flying towards Midway. At 0800, while patrolling near the northern boundary of her assigned area, the submarine, steaming to that place on the basis of the report, sighted a formation of four Japanese ships, which included the battleship Kirishima, the light cruiser Nagara and two destroyers. After being spotted by the enemy, Nautilus quickly submerged. A Japanese plane then strafed her while two destroyers began dropping depth charges.

At 0824, having endured the brunt of the initial attack, Nautilus ascended to periscope depth. Lt. Cmdr. Brockman later recalled the scene, stating, “The picture presented on raising the periscope was one never experienced in peacetime practices. Ships were on all sides and moving across the field at high speed and circling away to avoid the submarine’s position.” With Kirishima on her port bow and Nagara nearby, Nautilus fired a torpedo at Kirishima, which missed its mark, and then dove to weather a depth charge attack from Nagara and the destroyer Arashi.

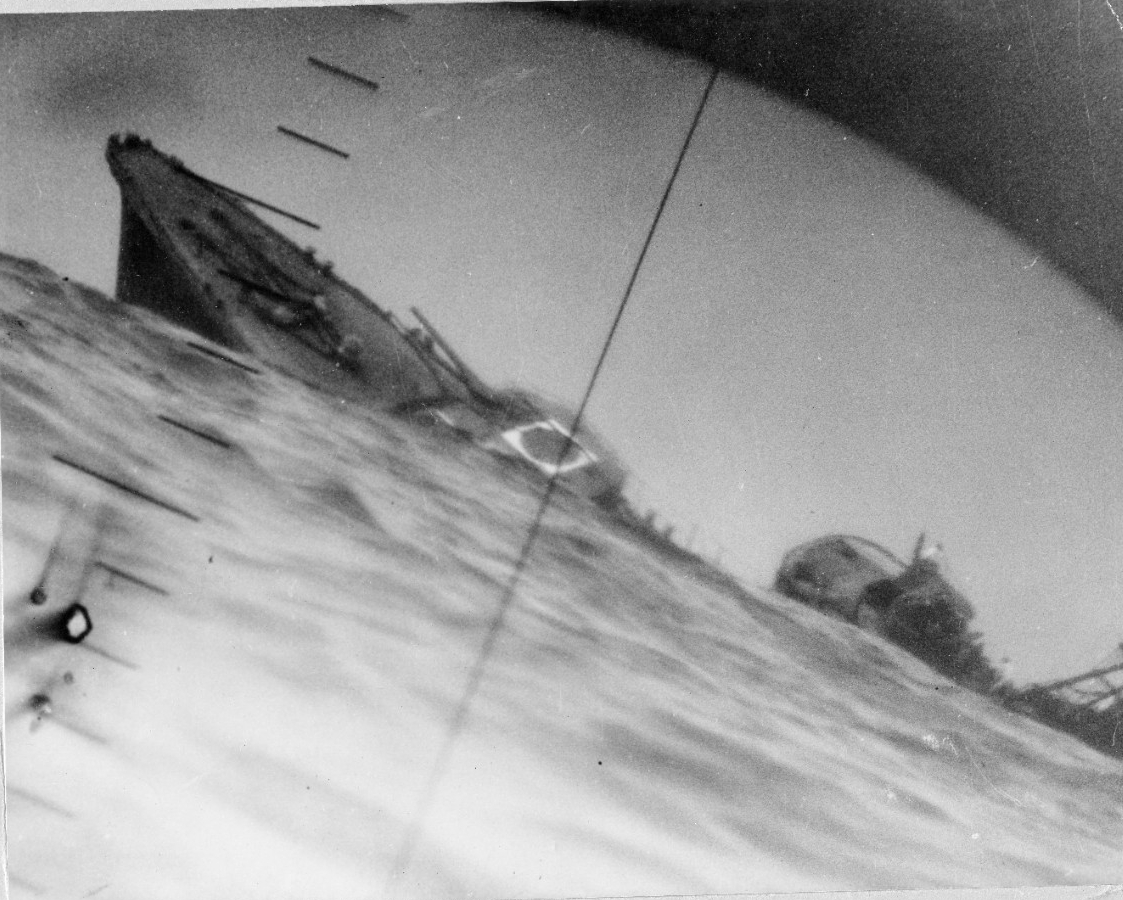

At approximately 1253, Nautilus picked up the carrier Kaga, along with two escorts, the destroyers Hagikaze and Maikaze. A few hours earlier, Douglas SBD-3 Dauntless dive bombers, from Bombing Squadron (VB) 6, attached to the carrier Enterprise (CV-6), scored several direct hits amidships of the carrier. Nautilus eagerly eyed the damaged carrier and maneuvered to an attack position at 1359. At 3,000 yards, Nautilus fired three torpedoes from periscope depth. At least one of her “fish” hit Kaga but failed to explode. Shortly after the failed torpedo hit “red flames appeared along the length of the ship from the bow to amidships” and “many men were seen going over the side.” Kaga’s escorts hurriedly reversed their course at high speed and Nautilus, out of torpedoes, dove in anticipation of a depth charge attack.

Nautilus endured a prolonged depth-charging following the daring attack on Kaga but at approximately 1610, she moved back up to periscope depth. Nautilus then observed the carrier being abandoned and an enormous fire “along the entire length,” which produced a heavy cloud of black smoke, estimated to be approximately “a thousand feet high.” The officer observing the scene, having been at Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941, said that it reminded him of the oil smoke that rose from the battleship Arizona (BB-39). Following a series of powerful subsurface explosions, observers from Nautilus concluded that the carrier “was destroyed by fire and internal explosions.” Hagikaze scuttled Kaga at approximately 1925 that night in accordance with a direct order from Adm. Yamamoto Isoroku.

The Battle of Midway resulted in a monumental victory for the U.S., and is considered to be a turning point in the Pacific Theater of the war. Four Japanese fleet carriers were sunk but the U.S. suffered the loss of one, Yorktown (CV-5), as well as the destroyer Hammann (DD-412). Nautilus’s submariners displayed tremendous courage during the engagement, attacking the enemy wherever encountered. In total, she expended five torpedoes, which, had they been higher quality (they were the Mk-14 steam torpedoes), they might have further damaged the Japanese fleet. For her acts of daring, she endured a total of 42 depth charges. Following the battle, from 5 to 7 June 1942, Nautilus replenished at Midway, then set course for her patrol area off the coast of Japan.

Peering through a dense fog on the morning of 25 June 1942, while patrolling the entrance to Sagami Wan [Bay], Nautilus sighted the Japanese transport Keiyo Maru and fired a salvo of torpedoes. Despite hearing several explosions the attack caused only limited damage and Keiyo Maru steamed out of the area. At approximately 0825 that same morning, 60 miles southeast of Sagami Wan, Nautilus encountered the destroyer Yamakaze and fired another spread, recording the first fish as a “bull’s eye,” striking beneath the number two stack, amidships, while the second hit forward, producing “terrific damage.” Yamakaze sank by the bow and heeled over at approximately 34°34'N, 140°26'E, taking with her Lt. Cmdr. Hamanaka Shuichi, her commanding officer, and his 227-man crew.

With a “glassy calm sea” and in clear sight of the coast of Nojima Saki, Japan, on 27 June 1942, Nautilus spotted the auxiliary minesweeper Musashi Maru and approached the vessel at periscope depth. A single torpedo fired from one of the submarine’s stern tubes resulted in a tremendous explosion and the appearance of flames aft of the vessel, which shortly thereafter sank by the stern. The next day Nautilus sighted the seaplane tender Chiyoda accompanied by the minelayer Ukishima. Nautilus fired three torpedoes at Chiyoda, but air bubbles unfortunately revealed her position and Ukishima counterattacked. The submarine underwent a grueling depth charge attack described in her records as “the worst ever experienced by this vessel.” Within just a few days, the severe impairment caused by the attack forced Nautilus to return to port.

The submarine departed her patrol area on 1 July 1942, and shaped a course for Pearl Harbor, where she arrived on the 11th. Her first patrol had been enormously successful, and marked by an astonishing level of aggressiveness and bravery. Despite being his first patrol and not having received the “normal training for a commanding officer,” Lt. Cmdr. Brockman had performed brilliantly and subsequently received the Navy Cross for his daring exploits during the Battle of Midway. The crew received a letter of commendation from President Franklin D. Roosevelt. A headquarters review of the patrol lauded the expedition asserting, “No opportunity to do damage to the enemy was missed.” In his concluding thoughts on the patrol, Lt. Cmdr. Brockman sagely observed, “The sinking of a ship increases morale and thereby increases endurance.”

Nautilus remained at port undergoing repairs until 7 August 1942. On the 8th she put out to sea on her second war patrol accompanied by Argonaut. After being escorted out of coastal waters by the submarine chaser PC-476, Nautilus set out to land marines from the Second Raider Battalion, commanded by Lt. Col. Evans F. Carlson, USMC, at Makin [Butaritari] Island, a small islet of the Makin [Butaritari] Atoll. The landing was part of a broader strategy meant to draw Japanese attention away from the Solomon Islands where the fight for Guadalcanal was in its early stages.

Both submarines arrived in the vicinity of Makin Island on the 16th and began circling the area, awaiting orders to disembark the Raiders, and ultimately, during the mid watch on the 17th, Nautilus and Argonaut began disembarking the marines. At 0408, the Raiders cleared both submarines and headed for the shoreline in rubber boats. A few hours later at approximately 0730, the Raiders launched an assault against Japanese troops at Ukiangong Point. In the fog of battle, however, some of the marines accidently landed behind Japanese lines and despite aggressively engaging them, were caught in a heavy crossfire from various machine gun nests. Several Japanese ships, a troop transport, and a patrol boat, were also observed in the lagoon near Ukiangong Point, and their presence caused the marines more than a little consternation, as they doubted they could escape if more Japanese troops were brought ashore.

Fortunately, for the Raiders, Nautilus’ proximity enabled her to open fire on the two vessels near the lagoon, sinking both. Shortly after the bombardment, an enemy aircraft flew through the area and Nautilus dove to evade it. The Japanese executed two aerial attacks on the area, the last of which landed additional reinforcements on the island. The Raiders withdrew from the fight at 1700, and meanwhile, Nautilus and Argonaut moved to a previously agreed upon rendezvous point. At 2046, Nautilus received four boats containing 53 marines and Argonaut received an additional three boatloads. A number of the Raiders, along with their commander Lt. Col. Carlson, remained on the beach because some of the other rafts were damaged and unable to make it past the surf.

Due to an inability to communicate with the marines on shore via radio, a single boat, with several volunteers, returned to the beach to inform Lt. Col. Carlson of a proposed rescue plan. At some distance from the shore, one of the men swam ashore to give Lt. Col. Carlson the information, and then swam back. With the return of volunteers, the submarines moved off from the shoreline.

Late in the morning the following day, Japanese planes dropped two bombs on the area at high altitude, but both “missed Nautilus by a great distance.” Nonetheless, the submarine prudently dove to 150 feet. At 1824 on 18 August 1942, Nautilus and Argonaut again attempted to extract the remaining marines, however, upon their approach Lt. Col. Carlson signaled Nautilus, and requested that the extraction point be changed to the lagoon entrance, near Flink Point at 2130.

In compliance with Lt. Col. Carlson’s, request Nautilus and Argonaut re-established contact with the remaining Raiders at the lagoon later that night, at about 2213. Shortly thereafter, the embattled marines arrived alongside the submarines in four rubber boats and one native canoe; all embarked by 2353. A subsequent analysis of the operation revealed that there were at least nine other marines still on the island who were eventually captured and executed by the Japanese. Unaware of this, within an hour of bring the last man on board, the two submarines set a course for Pearl.

During the voyage home, Lt. William B. MacCracken II, MC-V (S), USNR, an orthopedic specialist, operated on six seriously wounded marines, an exploit for which he later received the Navy Cross. Nautilus made port at Pearl on 25 August 1942.

The patrol had not been without other difficulties as well. The submarine’s poorly functioning air conditioning unit had done little to stem the 93-degree heat. Lt. Cmdr. Brockman observed, “The men seemed more tired after these operations than at any time during the first patrol. This was caused by lack of sleep and the extreme heat of the all-day dives.” He also noted, regarding the evacuation of the marines, that they “should not be given a definite time of withdrawal, but withdraw when the job is completed.” Upon returning to port, the submarine commenced a refit, which lasted until 7 September.

Following her upkeep period in the yard, Nautilus conducted sound listening tests, and then on 10 September 1942, stood out on her third war patrol to rejoin the numerous submarines blockading the Japanese coast from the Kurile Islands to Nansei Shoto [Ryukyu Islands]. She arrived at Midway on 14 September and moored alongside the submarine tender Fulton (AS-11). Nautilus departed the next morning at 0530, and although she encountered a number of mechanical issues, which resulted in “the engineers working day and night with little rest,” she finally reached her patrol area on the 23rd. The submarine sighted her first enemy ship “a patrol vessel, probably armed,” on the 24th. Despite high winds and inhospitable seas, which almost washed more than one man overboard, the submarine’s 6-inch guns managed to sink the Japanese vessel.

Late the following night, on 25 September 1942, Nautilus engaged a sampan with her .50-caliber machine guns, and a chase ensued. The submarine finally subdued the vessel just after midnight. On the 26th, she located another sampan and, despite firing on the vessel with her 6-inch, could not manage to set her on fire. At last, the crew brought out a bucket of “fuel oil rags,” and threw them on board the sampan, which shortly thereafter began to burn furiously. The evening of the 27th produced further excitement when a convoy of approximately six ships appeared just off the coast. Nautilus fired a salvo of torpedoes at 900 yards but both missed; nonetheless, determined to make the kill, two more were launched, one of which misfired and the other missed the target.

The enemy vessel, which hitherto had reaped the benefits of the poor quality of U.S. torpedoes, put up a smoke screen and proceeded to “skillfully” maneuver out of danger. Seeing her prey begin to slip away, Nautilus surfaced in one last effort to put the enemy vessel under. At 600 yards, four torpedoes and the submarine’s machine guns let loose on the vessel. A frustrating series of malfunctions took place in which more than one gun jammed and three tubes misfired. Despite these issues, fire from one of the machine guns and the successful launch of one of the torpedoes at last inflicted mortal damage. The enemy vessel sank by the stern and a fire raged amidships, as the crew “abandoned her frantically.” A salvo fired from a nearby shore battery splashed windward and drenched all hands topside, cutting short the boat’s investigation of the enemy wreckage. Nautilus dove and thereafter weathered a barrage of 32 depth charges.

Having survived the enemy’s retaliation, Nautilus re-surfaced a few hours later and began reconnoitering in the vicinity of Cape Erimo, and Hokkaido, Japan. On 30 September 1942, she sighted a freighter and attempted to fire two torpedoes, but both misfired and the vessel escaped. The next day while en route to Shiriya Saki Light the submarine sighted a “6,500-ton freighter.” Due to the glassy seas, she went deep, and at 0818, fired three torpedoes. With two observed hits, the target settled and Nautilus’ crew observed a lifeboat carrying approximately 25 men. A depth charge attack then ensued, which was believed to be from enemy planes, as no enemy ships were sighted in the area.

In the early morning hours of 3 October 1942, a Fubuki-class Japanese destroyer challenged Nautilus. She attempted to engage the warship but broke off the attack because “seas became so bad that it was impossible to maintain periscope depth.” A few hours later, she surfaced in still, rougher seas and higher winds, and headed for the coast of Honshu. She traveled in foul weather for the next two days and at last resumed a submerged patrol south of Kushiro on the 6th. The submarine observed numerous sampans in the area over the next several days but little other activity.

On 8 October 1942, a gale with “seas, 50 to 60 feet high,” engulfed the area. Running the submarine “with the waves,” Brockman decided to head back to Cape Erimo. “Mountainous seas, the largest any of us have ever seen,” marked the next several days during which time the ship endeavored to ride out the storm. Nautilus attempted to engage a freighter on the 12th, despite the tempest still being in full swing. However, the torpedoes that didn’t miss, misfired, and within moments of the attack a Japanese destroyer retaliated with a slew of depth charges that “shook them considerably.”

Nautilus managed to escape the perils of the former night’s melee but the combined effects of the typhoon and the last depth charging left her noticeably damaged. The first symptoms resulted in strange “noises in the hull,” and a marked difficulty in maintaining depth control. On 15 October 1942, Nautilus encountered an enemy destroyer but could not engage due to her damaged state; and at one point involuntarily rose to 60 feet before her ascent was stopped by the “the use of a negative tank.” She nonetheless, continued cautiously patrolling while dealing with her persistent mechanical issues. On the 14th, an oil slick appeared in her wake and by the 19th, the oil leak widened, considerably. The following day an air leak appeared and thus, due to the combined trail of oil and air the submarine moved on to an area with less enemy plane activity.

Nautilus sighted the Japanese freighter Kenun Maru on 24 October 1942, approximately 20 miles east of Shiriya Saki, Honshu, and despite her damaged state fired three torpedoes at the vessel. Two of the fish hit their target and left the enemy vessel broken amidships, “bow and stern high in the air, and a single screw completely out of the water.” The next day Nautilus spotted a sampan and assaulted the craft with her deck guns, leaving the boat “engulfed in flames” and burning furiously. Shortly thereafter, the submarine left the area and shaped a course for Midway. Approximately sixteen miles from her destination on the 31st, she made contact with the armed yacht Beryl (PY-23) and then shortly thereafter made port at Midway for temporary repairs.

Nautilus departed Midway on 1 November 1942 and shaped a course for Pearl. Several days into her voyage, Nautilus, while steaming in a glassy calm sea with light swells, observed a “dark object, later identified as a large glass float,” and noticed a heavy oil slick. Sound reported fast screws, “like a torpedo, bearing 140 relative, which then quickly changed to dead astern.” The bridge confirmed the presence of a torpedo wake and it seemed certain that the boat “would be hit.” Miraculously, the torpedo passed the submarine close by the stern. A subsequent search revealed no further evidence of an enemy submarine and the threat seemed to vanish as soon as it had appeared. She arrived safely at Pearl on 5 November.

During her third war patrol, Nautilus spent 31 days at sea, 16 of which she endured punishing weather, and in all expended 145,480 gallons of fuel. The success of the patrol highlighted the aggressiveness of her commanding officer, as well as, the stamina of her sailors. Her efforts had however, put her under great strain, and as a result, the submarine underwent an extended four-week refit that lasted from 6 November to 5 December 1942. In addition to mending her mechanical woes, the refit included the installation of SJ radar and four 20-millimeter guns, after which she conducted training (6-9 December).

She stood out of Pearl on the 13th and shaped a course for the area of the Solomons, for her fourth war patrol. On the 23rd the submarine crossed the equator and the crew erected a sign that read “Dear Santa Claus, please bring us a fat old Jap cruiser for Christmas.” She arrived in the area of the Ontong Java Atoll on 25 December, and took some pictures, but noted no enemy activity. She made it to her assigned patrol area early the next day.

On 29 December 1942, Nautilus received instructions to extract refugees located at Toep Harbor, on Bougainville Island, in the Solomons. With the rescue scheduled for the 31st Nautilus bided her time patrolling north of Cape Henpan. On the 31st she submerged ten miles from Toep Harbor and shortly afterwards arrived in the prescribed extraction area. A small party of men went ashore in a motor boat to make contact with the evacuees and at 0300, they returned with 17 women, three children and one man. Shortly after embarking, the evacuees were entertained in the crew’s mess hall and served a light supper. Women were given the officer’s quarters and the men had to “hot bunk,” while much of the boat’s crew slept on deck. Brockman found the crew’s treatment of the evacuees to be exemplary and later remarked that it seemed “there was not a thing that the men would not do for them.” On 4 January 1943, at 0310, Nautilus transferred her passengers to PC-476.

Early on the morning of 9 January 1943, approximately 22 miles east of Bougainville, Nautilus spotted and assailed a convoy consisting of two large merchantmen and a patrol boat. She fired three torpedoes at the last ship in the column and then dove in anticipation of a depth charge attack. One of Nautilus’s torpedoes proved fatal and at 06°10'S, 156°00'E, the auxiliary transport Yoshinogawa Maru sank with the loss of eight of her crew.

The submarine shifted over to another location on 14 January 1943, and again found herself in a scrape with an enemy convoy. She launched a spread of torpedoes at the transport ship Toa Maru, and two of them were believed to be direct hits. She then turned and fired a torpedo at one of the escort destroyers, which missed. For good measure, Nautilus then launched an additional salvo of torpedoes at Toa Maru. The submarine received no retaliation for her attack and after searching unsuccessfully for the destroyer, she concluded that the warship had “run away.” Unbeknownst to her crew at the time one of the torpedoes had in fact struck Toa Maru but failed to detonate and the vessel steamed to safety. With the action concluded Nautilus set a course for the eastern entrance of Buka Passage.

On 15 January 1943, Nautilus made contact with an unknown submarine off her starboard bow, and instantly dove; however, the other boat mysteriously disappeared. The following day, while conducting a submerged patrol in a glassy calm sea, north of Bougainville Strait, Nautilus observed and then fired a salvo at an armed merchant ship bearing 6,500 yards distant. The vessel maneuvered to avoid and none of the torpedoes made their mark. Screws were heard shortly afterwards and a depth charge attack commenced. Brockman described the enemy captain as being quite skillful given that “his charges seemed to jar us more than others,” and that in brief “he was good.” Following a prolonged siege, the submarine managed to escape.

Nautilus steamed for Kieta Harbor, Papua New Guinea, on 17 January 1943. On the 18th, she redirected to the east side of Buka and Bougainville to conduct a bombardment with Swordfish (SS-193) and Gato (SS-212). During a routine surface patrol, late the next night, Nautilus sighted the destroyer Akizuki at 05°55'S, 156°20'E and “let him have it with the bow tubes,” firing two torpedoes—one of which hit its mark. Akizuki returned fire with her large and small caliber guns. Nautilus launched an additional three torpedoes at a range of 500 yards but all of them failed to explode. Brockman recalled that the failure of the torpedoes “was hard to take because we thought we had the enemy in the bag.” The submarine attempted to withdraw from the area by zigzagging but Akizuki proved to be persistent and the chase lasted into the mid-watch.

A week later, on 28 January 1943, Nautilus sighted smoke while conducting a submerged patrol east of Queen Carola Harbor, Papua New Guinea. A small convoy consisting of a merchantman and a destroyer soon came into view and the submarine fired three torpedoes at the merchantman. Two of the fish struck the enemy vessel aft, and Nautilus then focused on the destroyer who had already started a depth charge attack. Two more torpedoes fired off at the destroyer but neither of them hit the target. The submarine then “remained deep,” and endured 12 depth charges. Air bubbles appeared shortly after the attack concluded and Brockman remarked that he had “no further desire for trouble,” and headed south. Despite her declining condition, at 0227 the next morning, Nautilus again engaged enemy convoy. She fired her last two torpedoes at a large supply ship and a destroyer. One of the torpedoes hit the destroyer and “stopped her screws,” but the cargo vessel fled.

Nautilus departed her patrol area on 31 January 1943, and arrived at Brisbane, Australia, on 4 February. From there she steamed to Pearl where she arrived on 15 April. In addition to her aggressive actions against the enemy and the rescue of evacuees, Nautilus’s fourth war patrol was also unfortunately marked by a degree of sluggishness as a result of inadequate air conditioning. The highest room temperatures were recorded at 104° degrees, with 96 percent relative humidity, and there were two cases of heat exhaustion.

Having ended her fourth war patrol at Pearl Harbor, Nautilus remained there for five days afterwards to undergo a brief refit. She shipped out again on 20 April 1943, for her fifth war patrol. The boat steered north on a mission to assist the U.S. Army with the Aleutian Campaign, which sought to dislodge Japanese forces that had previously seized the remote U.S. islands of Attu and Kiska, T.A., in June 1942. On her journey, she encountered heavy seas, which compounded some of her persistent mechanical issues. On a day of particularly bad weather Brockman noted “The engineers must be complemented on their devotion to duty… they have been working continuously for close to twenty-four hours in mountainous seas with winds up to 60 knots.”

The submarine put into Dutch Harbor, on 27 April 1943, and went alongside the oiler Guadalupe (AO-32) to fuel. Nautilus then set about her mission training with the Seventh Infantry Division Army Scouts for amphibious operations that were to take place in the Aleutians. In training with the Army Scouts, Brockman noted that they “responded to our training better than any group we have had on board.”

After several days of exercises and drills, on 1 May 1943, she embarked 109 of them and steamed to Attu, one of the most remote islets of the Aleutians, located in the Bering Sea. She arrived in the area of Attu on the 5th and proceeded to reconnoiter the island, allowing the Army officers on board to get a look at the beach where they would be landing. Inclement weather postponed the day of the attack four times and meanwhile, Nautilus impatiently loitered around the area. As a precaution in the event of her capture, at 0030 on 9 May, Nautilus’ crew, not without “some misgivings,” smashed her Electronic Countermeasure gear, and threw it overboard.

Just after midnight on 11 May 1943, the Army Scouts ate a large steak dinner and at 0134, they started getting ready for their assault in the gun access hatches. At 0202, just a few hours ahead of the main assault and some three miles off the beach, Nautilus successfully disembarked the soldiers, who landed in the dark with only their pocket compasses to guide them. For the soldiers, the ensuing battle raged from the 11th to the 30th and featured some of the Pacific Theater’s fiercest and bloodiest ground combat.

With her services rendered, Nautilus departed the area on 12 May 1943, and set a course for Dutch Harbor to patrol for enemy shipping. She encountered heavy seas on her voyage, conducted entirely by “dead reckoning,” and arrived at Dutch Harbor on the 16th. The next day the submarine set out for Pearl but received a message on the 18th instructing her to change course for Mare Island, a development which “increased the morale of the crew to one hundred percent.” The boat arrived at Mare Island on 25 May, ending her fifth war patrol, and then underwent an extended overhaul there.

Following a brief training period at Pearl, Nautilus stood out on 16 September 1943 to commence her sixth war patrol conducting photo reconnaissance of the Gilbert Islands, namely the islets of Tarawa, Kuma, Butaritari, Abemama and Xlakiri. On the 24th, she took photographs of a lookout tower located on the south end of Tarawa and over the course of the next week gathered significant intelligence on enemy activity in the area. On the 30th, she surveyed the coast of Abemama, where, on the 2nd, she “came face to face with two excited Japs doing sentry duty in the tower,” and as Lt. Cmdr. William D. Irvin, the boat's new commanding officer (who had served on board in 1937-1938), recalled, based on the gestures of the sentries “it was time to end the observation.” The boat then went deep and set a course for Makin Atoll.

On 8 October 1943, the submarine scouted Makin, and reported her mission to be complete as of the 10th. Late that afternoon [10 October], while steaming in a glassy smooth sea, Nautilus sighted a small island tanker and attacked the vessel with three torpedoes at 2,000 yards. Unfortunately, none of the torpedoes hit their target and in reprisal, the submarine endured an hour-long siege, which featured eight depth charges and three aerial bombs.

Nautilus kept a low profile for the next week, but on 17 October 1943, she spotted a coning tower, which Lt. Cmdr. Irvin at first believed to be a newer model U.S. submarine. In fact, they had lost likely encountered the Japanese submarine I-35 (Lt. Cmdr. Yamamoto Hideo, commanding). At 0300, with I-35 having moved on, Nautilus set a course for Pearl and upon reaching her destination ended her sixth war patrol. In total, she had spent 18 days in her assigned area and procured valuable panoramic pictures and chart corrections.

From 17 October to 5 November 1943, Nautilus underwent a refit at Pearl. During the refit, a broken freewheeling clutch was identified on engine four. As it was the third time one of these clutches had broken the issue was subsequently deemed to be a design weakness. Notwithstanding her mechanical issues, on 8 November Lt. Cmdr. Irvin and his crew, having enjoyed a brief respite at Pearl, again prepared to venture out to sea. For her seventh war patrol, Nautilus set out to land a contingent of marines on Abemama, in preparation for a general assault being launched in that area, as part of the Marshall Islands Campaign.

For the mission, Nautilus embarked one Australian scout and 78 marines from the 5th Amphibious Reconnaissance Corps., under the command of Capt. James L. Jones, USMC. She got underway at 1300, but quickly started having mechanical issues. The following day she diverted her course to Johnston Island to undergo further repairs and arrived there on 11 November 1943. Although certainly perturbed by the continuing mechanical issues, Lt. Cmdr. Irvin did receive, as a gift from the commanding officer at Johnston, “two very large fish in a box of ice,” which slightly improved morale.

With her repairs completed, Nautilus put out to sea on 12 November 1943, and following nearly a weeklong voyage arrived in the Gilbert Islands on the 16th. On the 18th, the submarine investigated the area around Bititu [Betio]. The following day at 1125, she observed U.S. naval forces conducting a bombardment of the island and later that night, at approximately 2200, she came into view of the destroyer Ringgold (DD-500). Upon sighting the submarine, Ringgold immediately started shelling her. According to Lt. Cmdr. Irvin, “it was a clear case of shooting first and asking questions later.” Nautilus fired a green recognition flare, but too late, as one of Ringgold’s projectiles, a 5-inch shell hit her conning tower just as the hatch closed shut. Nautilus dove and water poured in through her induction drain with torrents more of it coming down the conning tower itself.

During the early morning hours of 20 November 1943, Nautilus’s crew was hard at work endeavoring to bring the damage from the former night’s “friendly fire” incident under control. The Commander in Chief U.S. Pacific Fleet (CinPacFlt) was notified of the attack and an inquiry was later conducted by Adm. Chester W. Nimitz. In reflecting on the incident, Lt. Cmdr. Irvin, who would later be awarded the Navy Cross for his leadership during the incident, insightfully noted “we learned bitterly the truth of the maxim, the submarine has no friends.” He added that following the attack, the marines seemed anxious to get off the ship, as they “had determined that torpedo rooms were not satisfactory foxholes.” Despite the damage she sustained, Nautilus continued on with her mission and as the day wore on, she “touched the equator,” although Lt. Cmdr. Irvin noted that “the resident King Neptune was too tired to hold court.” Also, in order to assuage the marines’ anxieties, Lt. Cmdr. Irvin moved Thanksgiving dinner up a few days so that that they could have a feast before leaving the ship.

The submarine took up a position 3,000 yards off Kenna Island on 21 November 1943. At 0045, the landing force disembarked and shortly thereafter made it safely to shore. Nautilus dove, established radio contact with the marines, and then stood by to await further orders. Over the course of the next several days, Nautilus provided vital fire support, bombarding several enemy shore installations. Meanwhile, the salvage vessel Clamp (ARS-33) got underway to repair Nautilus.

On 23 November 1943, Pfc. Harry J. Mareck and Cpl. John F. King, two wounded marines, who were in need of blood plasma, were brought to the ship on a small boat. Cpl. King survived but despite great efforts, Pfc. Mareck died. The next day a funeral service for Mareck took place at 0445 and his body was committed to the sea. Later that morning at 0748, Nautilus performed a shore bombardment and destroyed a key enemy gun emplacement.

Late in the afternoon on 24 November 1943, the tug Mataco (AT-86) arrived and assessed the damage done to Nautilus. Meanwhile, Cpl. King was delivered to Clamp and then a few days later, after determining that repairs could not be made at sea, Mataco began escorting Nautilus to Johnston Island. However, while en route on the 28th, they redirected their course to Pearl. Nautilus arrived at her destination on 4 December, ending her seventh war patrol. While in port, the submarine began an extended refit period because of the immense damage she had suffered and was not ready for sea again until the last week of January 1944.

Mended at last, Nautilus got underway on 24 January 1944, to conduct her eighth war patrol, north of the Palau archipelago, and west of the Marianas. The submarine arrived in her assigned area on 12 February, at a noted expenditure of 51,945 gallons of fuel, a fact that necessitated her running submerged for at least the first 20 days of the patrol. She had little luck locating enemy ships for the rest of February, but on 1 March, she finally happened upon a column of them and promptly fired a salvo of torpedoes. Both reportedly hit the target but the extent of the damage could not be fully assessed, as the boat had to dive because of a depth charge attack.

Two days later Lt. Cmdr. Irvin set a course for Midway due to a fuel shortage. While en route on 6 March, Nautilus came upon another enemy convoy at 22°19'N, 143°54'E, and subsequently engaged them. She struck the transport (ex-hospital ship) America Maru between her after stack and after mast, as well as at her stern. Nautilus then dove as a depth charge attack began and shortly thereafter continued on her course. When struck by Nautilus, America Maru had been en route to repatriate 551 civilian evacuees from Saipan, primarily consisting of women and children. Only 43 of the 642 on board were rescued.

With fuel running low on 12 March 1944, Lt. Cmdr. Irvin was still hoping to make it to Pearl. On the 14th however, the main engines started billowing black smoke and making Pearl became an impossibility. On the 16th, Nautilus moored at Midway, where she took on fuel, warheads and 102 passengers. She got underway for Pearl again that same day at 1604.

Following a short voyage, Nautilus arrived at Pearl on 21 March 1944, and commenced a refit period during which her crew enjoyed some much needed recuperation. Overall, it had been a successful 58-day patrol. Two excellent remarks were made in the ship’s log, the first being the torpedo officer’s observation that “the Mark 18 torpedo is superior to the Mark 14,” an improvement appreciated by all submariners, and second, Lt. Cmdr. Irvin’s insight that “compared to that of newer submarines, the slow speed of the Nautilus was an appreciable handicap during the patrol.”

The submarine’s refit and training period ended on 25 April 1944, and with a new commanding officer, Cmdr. George A. Sharp, at her helm; as well as, 20 other newly acquired crewmembers, she set out on her ninth war patrol headed for Brisbane. The submarine arrived in Brisbane on 14 May and moored at New Farm Wharf. Six days later, on 20 May, she stood out and proceeded to Darwin, Australia, via the inland passage of the Great Barrier Reef and the Torres Strait, transporting a cargo of “assorted goods.” Nautilus arrived at Darwin on 28 May, and after unloading her cargo, she loaded up for her next mission. On the 29th, Lt. (j.g.) John D. Simmons, USNR, reported on board for transportation to Tukuran, Allana Bay Mindanao, where he was charged with helping to establish a communications network to support ongoing operations in the area. In addition to Lt. (j.g.) Simmons, Nautilus took on a supply of ammunition, oil, and dry stores.

On 2 June 1944, while transiting the Bangka Strait in glassy clam waters, Nautilus encountered an enemy patrol craft, which closed on her “while firing continuously.” The submarine went deep and the danger passed. On the 5th she arrived off the beach of Tukuran and shortly thereafter observed the proper security signals on shore. Col. Robert V. Bowler, USA, had approximately one thousand men on the beach preparing for the boat’s arrival. A group of ten men from shore made contact with Cmdr. Sharp and shortly thereafter more rafts arrived and began transporting and unloading the cargo. Lt. (j.g.) Simmons also disembarked at that time.

Nautilus departed the area and as of 7 June 1944, she headed for the Siaoe Passage. On the evening of the 7th, she sighted a small, two mast auxiliary schooner and opened fire on the craft at 1,300 yards, with her 6-inch. After three salvos, she broke off the attack with inclusive results. On the 11th, at 0821, the submarine arrived back in Darwin and moored, port side to Boom Jetty, ending her ninth war patrol. Reflecting on the patrol Cmdr. Sharp observed that during the unloading at Mindanao there was a serious “lack of organization and supervision of the work party from shore,” and that 98 tons “is too much to unload in one night.”

The day after she completed her ninth war patrol Nautilus stood out from Darwin on her tenth, laden with cargo similar to that of her previous missions and the submarine headed to Negros Island. While en route on 14 June 1944, the submarine engaged a schooner of approximately 100 tons; closing on the small vessel at 5,000 yards, and then subjecting her to a heavy cannonade. The beset crew “doused their sail,” and abandoned ship. Nautilus noted five survivors on two lifeboats as she left them in a sinking condition.

On the 18 June 1944, Nautilus arrived in the vicinity of Negros Island. On 20 June, she stood in to Balatong Point and at 1945 embarked Lt. Col. Salvador Abcede. In addition to Abcede, 17 evacuees and one German prisoner of war were also brought on board. Meanwhile, four Filipino army enlisted men and the boat’s cargo were transported to shore. All the cargo cleared the submarine by 0621 on 21 June, and shortly thereafter, she headed for Darwin.

Nautilus spotted a small sailing vessel on 25 June 1944, which “bent on all canvas, presented their stern and made a run for it.” Nautilus fired a salvo from her No. 1 gun at a range of 2,500 yards, leaving nothing left of the vessel except “a hulk of splintered timbers.” In total, 18 Malayan survivors were pulled out of the water. Upon further examination by Lt. Jon Wooster, an embarked evacuee, it was discovered that “the boat was bound for Ambon under Japanese charter with 12.5 tons of pistol and rifle ammunition.” The survivors also claimed that the Japanese shaved their heads and took most of their money. On the 27th, the cargo ship, HMAS Malanda came alongside Nautilus and received the evacuees and survivors. The submarine then moored at Boom Jetty in Darwin, ending her tenth war patrol.

Nautilus underwent some minor repairs at Darwin and loaded stores for her upcoming mission. In addition to her cargo, she also embarked 22 enlisted men, and four U.S. Army soldiers. On 30 June 1944, packed to the brim with supplies and men, the submarine departed Darwin on her eleventh war patrol. Nautilus arrived at the northern end of Pandan Island, near Sablayan Point on the 8th and three men went ashore to conduct reconnaissance. After receiving an all clear from the men on shore, the unloading of cargo and passengers began “hove to at an average distance of 500 yards from the beach.” Unloading the 12 tons of cargo took four trips and lasted until 0203 the next day. Having completed her duties, Nautilus weighed anchor and set out for the second part of her voyage.

On 14 July 1944, Nautilus arrived off San Roque and after observing appropriate security signals from the shore, then received boats of men from the north side of the island. Col. Ruperto Kangleon, the commander of the forces on shore, arrived and unloading began. It took until 0041 the next morning for all the cargo to get clear of the boat. The submarine then departed the area and headed for the Sulu Sea. She stood in at Balatong Point on the 16th and delivered more cargo to Col. Abcede at Mindanao. Following the delivery, Nautilus shaped a course for the Sibutu Passage, which she transited the following day. The submarine arrived at Fremantle, Western Australia, on 27 July, and ended her patrol.

During her eleventh patrol, Nautilus had completed three special missions and although she did not inflict any damage against the enemy, the patrol was nonetheless, designated as being successful for the wearing of the Submarine Combat Insignia. In total, the submarine had been underway for 87 days and steamed over 20,300 miles. Cmdr. Sharp’s only complaint being that “the ship was short of coffee for the last week of the patrol,” a ration scarcity loathed by any serious military man.

Upon reaching port in Australia, Nautilus underwent a refit. Cmdr. Sharp and the rest of the crew enjoyed a 15-day recuperation period at the Majestic Hotel and the Ocean Beach Hotel respectively. The respite was certainly “needed and enjoyed by all hands.” While the crew refreshed themselves, Nautilus’s main engine received an overhaul and she was dry-docked for bottom work. She then got underway for training on 27 August 1944 and steamed out for the waters around Darwin. She conducted training and drills until 5 September and then made port in Darwin, mooring to the port side of the submarine rescue ship Coucal (ASR-8). With voyage repairs complete, Nautilus brought on board 106 tons of cargo and two enlisted Army personnel for transport.

For her twelfth war patrol, Nautilus operated in the central Philippines from 17 September to 6 October 1944. She began, getting underway on 17 September, on a Top Secret supply mission. At first, she preceded via the bombing restriction lane to the Banda Sea, and then on the 25th arrived five miles off the southeastern point of Central Visayas Island in the Philippines. While observing the “target beach,” Nautilus’ crew observed a small boat standing out from the coastline waving a small American flag. It was also noted that the occupants of the vessel displayed the “length of their hair to demonstrate their nationality.” Nautilus surfaced and at 1911, a shore party came out on two small boats and began unloading the submarine’s cargo. In addition to the supplies she delivered, Nautilus received captured documents, mail, and eleven evacuees.

At approximately 2209, Nautilus ran aground on the Iuisan Shoal in approximately 18 feet of water, and located at approximately 09°33'N, 13°6'E. Cmdr. Sharp first attempted to back Nautilus up and in so doing blew her main engine ballast. As midnight neared all efforts appeared to be futile. At 0003 on 26 September 1944, Cmdr. Sharp gave the order to lighten the ship, moving the evacuees, mail, and other cargo to shore, and waited for high water to come in at 0400. All secret and confidential documents were burned. Her reserve fuel tanks were blown dry, the variable ballast blown overboard and the 6-inch ammunition jettisoned. Finally, at 0336 after blowing her main ballast tanks, the tide came in and Nautilus cleared the reef. Undoubtedly perturbed, the boat’s crew re-loaded her cargo and departed the area.

On 28 September 1944, the submarine conducted reconnaissance off the shoreline of Libertad, Philippines. On the 29th, she surfaced and opened her hatches for three large sailboats that came out from the beach and delivered 47 evacuees, including 22 women, 9 children and 16 men. Food and supplies were sent back to shore with the boats and Nautilus continued on her voyage.

On 6 October 1944, the submarine arrived within view of Mios Woendi Island, New Guinea, and shortly thereafter moored to the port side of the oiler Salamonie (AO-26). Once at anchor Nautilus disembarked her 48 evacuees and two enlisted army passengers, both of whom were noted to have been fine “shipmates,” who “conducted themselves in the highest order and accomplished more than their share of the ship’s work.”

Upon her arrival at Mio Woendi, Nautilus ended her twelfth war patrol. The successful completion of her mission and the admirable manner in which her crew had performed their duties earned them the honor of wearing the Submarine Combat Insignia Award. Even the loss of sleeping space due to the presence of cargo and evacuees was met and borne by “all hands with a light heart.” While at Mios Woendi the boat also underwent some minor repairs and upkeep, effected by the submarine tender Orion (AS-18).

Nautilus conducted her thirteenth war patrol off the east coast of Luzon, in the Philippines. She got underway from Mios Woendi on 10 October 1944 and arrived at her destination on the 21st. After completing her initial investigation of the coast, she received indications from a party of troops on shore that they had been ambushed. As such, the submarine remained off shore for the next two days awaiting instructions and at last on 23 October, received the “appropriate security signals.” At 1850 that same day, a shore party in a small boat came out to Nautilus and delivered passengers and cargo. At dawn on the 24th, the boat had to submerge to 90 feet due to the arrival of an unknown aircraft. She re-emerged at 1908 and continued unloading, which did not conclude until the 25th.

With the cargo delivery at Luzon completed on 25 October 1944, Nautilus made a quick turnaround and arrived at Dibut Bay that same day to make a second delivery. On 29 October, Nautilus received orders to destroy the submarine Darter (SS-227), which had run aground on Bombay Shoal. Nautilus located Darter at 08°26'N, 117°01'E, on 31 October. Upon sighting her, Nautilus surfaced and commenced firing, utilizing all of her high capacity projectiles and “concentrating fire on the conning tower and control room.” Upon ending the barrage, the crew observed “large explosions from one end of the ship to the other with dense yellow smoke in the vicinity of the control room and a huge oil fire aft.” Cmdr. Sharp felt confident that with the damage inflicted it seemed “very doubtful that any equipment in Darter would fall into Japanese hands, except as scrap.” Nautilus then departed, leaving Darter aflame.

On 9 November 1944, Nautilus arrived at Mios Woendi and moored alongside Orion. She received some officers and enlisted men on board, as well as, 7.5 tons of spare parts for transportation to Brisbane. She got underway the next morning, and following an uneventful voyage, arrived at New Farm Wharf, on the 20th. The submarine spent 25 days in her assigned area on the patrol and successfully completed all of her missions.

While at New Farm Wharf, Nautilus underwent a refit by Advance Training and Relief Crew No. 5. Her training period lasted from 20 to 24 December 1944. In preparation for a re-supply mission to Mindanao, the boat received 95 tons of cargo. She stood out from New Farm Wharf on 3 January 1945 and headed for Darwin via the bombing restriction lane.

The voyage, which constituted Nautilus’s fourteenth war patrol, got off to a shaky start. On the 4th, her main engine’s electrical circuit went out of commission and could not be repaired until the 6th. Nonetheless, she made it to Darwin by the 13th and moored to the starboard side of Coucal. That same day the boat received a change of orders, and following repairs and a brief re-supply on the 14th, she was underway again at 1245.

While submerged off Linao Bay, Mindanao, on 20 January 1945, Nautilus sighted a motor whaleboat standing off shore, hoisting “Old Glory,” which was by all accounts “a welcome sight.” At 1915, the submarine received a small U.S. Army shore party on board and commenced unloading 45 tons of cargo. Nautilus stood out from the area at 2358 that same day, and headed for Baculin Bay.

The submarine reached her destination on 23 January 1945, at approximately 0700, and although she initially spotted “the proper security signals on shore,” they remained up all day, which was “not in accordance with instructions,” and, as a result, Cmdr. Sharp deferred making contact. Later in the afternoon, a banca (indigenous Philippine boat) was observed flying a U.S. flag and “having quite a time of it in the seaway.” Nautilus surfaced at 1905, and embarked a shore party from the banca. Having made successful contact, the submarine then maneuvered into the bay and began unloading her cargo. All stores were ashore by 0119 on the 24th, after which, Nautilus set a course for Darwin.

After 28 days at sea, the war-weary Nautilus, hounded to the last by ongoing mechanical issues, undoubtedly the result of her prolonged years of service, arrived at Darwin on 30 January 1945. She moored to the starboard side of Coucal, and ended her final war patrol. The submarine’s two successful special missions during the patrol yet again earned her crew the Submarine Combat Insignia, and thus further added to her incredible record of valiant service.

From Darwin, Nautilus steamed to Balboa, where she arrived on 16 March 1945. From there she proceeded to Philadelphia, arriving on 25 May, and a month later on 30 June, the mighty Nautilus was decommissioned. Presiding over her decommissioning ceremony, Lt. Cmdr. Willard De L. Michael, her last commanding officer, addressed the crew stating, “Well men, I guess that’s about all for the Nautilus. She’s been a grand ship… I can’t say much else.” He then handed a bottle of champagne to Ens. John Sabbe, a veteran of all fourteen of Nautilus’s war patrols, who then proceeded to smash “the bottle over the breech of the forward six-inch gun,” proclaiming, “Nautilus, I decommission thee!”

Nautilus was stricken from the Navy Register on 25 July 1945, and then sold on 16 November, to the North American Smelting Co., Philadelphia, Pa., for scrapping.

Few submarines in the U.S. Navy can lay claim to a record as prestigious as that of the third Nautilus. From her participation in the opening act of the Battle of Midway, to the havoc she wreaked on Japanese shipping, Nautilus, and the crews who manned her were a true testament to the endurance and tenacity of the U.S. submarine fleet in WWII.

In addition to her Presidential Unit Citation, given for her exceptional aggressiveness in enemy waters, Nautilus was also awarded 14 battle stars for her service in WWII.

Commanding Officers |

Date Assumed Command |

Lt. Cmdr. Thomas J. Doyle, Jr. |

1 July 1930 |

Lt. Cmdr. Paul R. Glutting |

4 June 1932 |

Lt. Cmdr. James Fife |

5 June 1935 |

Lt. Cmdr. Alf O. Bergesen |

30 December 1937 |

Lt. Cmdr. Lloyd D. Follmer |

3 July 1940 |

Lt. Cmdr. Joseph P. Thew |

30 June 1941 |

Lt. Cmdr. William H. Brockman, Jr. |

10 February 1942 |

Cmdr. William. D. Irvin |

24 August 1943 |

Cmdr. George A. Sharp |

18 April 1944 |

Lt. Cmdr. Willard de L. Michael |

17 December 1944 |

Jeremiah D. Foster

18 December 2018