H-025-1: Operation Galvanic—Tarawa and Makin Islands, November 1943

H-Gram 025, Attachment 1

Samuel J. Cox, Director NHHC

31 January 2019/revised 7 December 2021

Operation Galvanic Background

Following the Japanese victory in the Russo-Japanese War in 1904–1905, and a “war scare” with Japan in 1906–1908 (provoked by discriminatory anti-Japanese immigration policy in the U.S.), the U.S. Navy began preparing for the possibility of war with that country. This effort would result in the development of War Plan Orange (and the subsequent “Rainbow” series of war plans). Although modified over the years, the basic outline of War Plan Orange would remain intact during the inter-war years. War Plan Orange assumed that the Philippines (then an American territory and later Commonwealth) would probably be lost, or at best besieged/blockaded by the Japanese, and that the U.S. Navy would have to fight its way across the Central Pacific to a climactic Mahanian battle of battleship fleets near Japan. The Japanese developed their own plan, in which they demonstrated an understanding of the U.S. plan: Japanese forces would counter it, attriting the U.S. Navy advance by using asymmetric means ( aircraft carriers, submarines, massed torpedo attack, and night battle), but with the same end result of a climatic battleship battle near Japan that would decide the war.

A key part of both the U.S. and Japanese war plans involved the possession of the Marshall Islands, an archipelago of coral atolls hundreds of miles across, including Kwajalein Atoll (with the world’s largest lagoon) located roughly 2,100 miles west southwest of Pearl Harbor and 1,000 miles east southeast of the Marianas Islands (which included Guam, Saipan, and Tinian). Possession of the Marshalls would be critical for the U.S. Navy to establish logistics facilities with which to sustain an advance across the Pacific. Although the United States had acquired Guam from Spain as a result of the Spanish-American War, Guam did not have an adequate harbor, nor did any of the other Marianas, nor islands such as Wake Island (also a U.S. possession).

However, during World War I, Japan was allied with the United Kingdom and captured the Marshall Islands from the Germans, who had bought them from Spain after the Spanish defeat in the Spanish-American War. After the end of World War I, the newly formed League of Nations awarded Japan a “mandate” to continue possession of the Marshall Islands, and other island chains that the Japanese had taken from the Germans, including the Caroline Islands with the magnificent lagoon and harbor of Truk Island. Article 22 of the League of Nations Covenant forbade Japan (or any other nation) from fortifying or using mandated territories for military purposes. The terms of the Washington Naval Treaty also precluded the United States from fortifying islands in the Central Pacific, such as Guam and Wake, which was a precondition for the Japanese to agree to a lower ship ratio, the famous 5-5-3 (U.S.-UK-Japan) ratio for battleships. For most of the interwar period Japan adhered to the terms of the League of Nations’ mandate, but as tensions began to rise, Japan turned administration of the islands over to the Imperial Japanese Navy in 1937 and clamped a tight lid of secrecy over its activities in the Marshalls. This provoked a significant U.S. Navy intelligence collection effort (which would result in persistent rumors that Amelia Earhart’s fatal around-the-world flight in 1937 was some sort of covert intelligence collection effort).

By 1940, the Japanese (and most of the rest of the world) were ignoring anything the League of Nations said, along with ignoring the Washington and London Naval Treaties and arms control agreements (particularly the Kellogg-Briand Pact of 1928, which “outlawed” war). The Japanese rapidly peppered the Marshal Islands with airfields, seaplane facilities, submarine facilities, and fortifications. The U.S. Pacific Fleet was fixated on the Marshall Islands as the primary threat vector to Pearl Harbor, and, in fact, the force of over 25 Japanese submarines in Hawaiian waters on 7 December 1941 sailed from Kwajalein in the Marshalls (the Japanese carriers, however, did not, and attacked Pearl Harbor from the north).

Upon the outbreak of war, the Japanese quickly moved (10 December 1942) to occupy a chain of similar coral atolls to the south-southeast of the Marshalls, called the Gilbert Islands, then under British administration (and now the nation of Kiribati). The United States responded with a carrier raid on the Marshall and Gilbert Islands on 1 February 1942, one of the very first U.S. offensive actions of the war. Task Force 8, under the command of Rear Admiral William F. Halsey, Jr., embarked on USS Enterprise (CV-6), attacked Japanese facilities and shipping in the Marshall Islands of Kwajalein, Wotje, and Maloelap (Taroa.) Task Force 17, commanded by Rear Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher, embarked on USS Yorktown (CV-5), attacked the Marshall Islands of Jaluit and Mili, and the Gilbert Island of Makin. U.S. cruisers and destroyers also bombarded Wotje and Taroa. The U.S. aircraft losses in the raids were not insignificant, results were limited, and the heavy cruiser USS Chester (CA-27) was hit and lightly damaged in a Japanese counter-airstrike, but the raids did provide vitally needed combat experience for the U.S. Navy carriers and aircraft, as well as being a big boost to morale in the Fleet and in the United States, still reeling from the disaster at Pearl Harbor.

On 17–18 August 1942 the 2nd Marine Raider Battalion, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Evans Carlson, was inserted onto Makin Island in the Gilberts by submarines USS Nautilus (SS-168) and USS Argonaut (SS-166). The raid was moderately successful, although the extraction proved very harrowing, and nine Marines were inadvertently left behind, captured and executed by the Japanese, in addition to 30 other Marines killed or missing. Marine General Holland M. “Howling Mad” Smith would later describe the raid as a “piece of folly,” in that it stimulated the Japanese to significantly increase the fortifications on Tarawa and Makin Islands, and, by July 1943, the defenses on Tarawa were quite formidable.

During the period when General MacArthur was still bogged down in New Guinea and Vice Admiral Halsey was meeting stiff Japanese resistance in the central Solomon Islands, the Allied Combined Chiefs of Staff approved making the Marshalls a priority target, and, in June 1943, Admiral Nimitz was directed to plan to take the Gilberts—as a stepping stone—and then the Marshall Islands by the end of 1943. Tarawa, as the only island in the northern Gilberts with an airfield, was identified as necessary to take first in order to bring the Marshalls in range of bombers and aerial photo-reconnaissance, as detailed intelligence of the Marshalls was lacking, although some had been obtained by submarine reconnaissance missions. The island of Nauru, about 380 miles west of the Gilberts, was originally identified as a target for invasion as well due to its potential to provide air support to Japanese forces in the Gilberts, but was later dropped when terrain and threat analysis determined it to be “too hard,” and Makin Island in the Gilberts was substituted as it was suitable for building an airfield.

Because the Marshalls and the Gilberts were literally in the middle of nowhere, as a preliminary step to eventually capturing the Marshalls, on 2 October 1942 the United States had established a bomber base and fleet anchorage at Funafuti Atoll in the Ellice Islands (under British administration,) 700 miles southeast of Tarawa, which was the closest the Allies could get with a land-based airfield. This resulted in some of the longest bombing missions of the war to that point, mostly by the United States against the Gilberts, and a handful of return strikes by Japanese bombers against Funafuti. By the end of August 1943, the Combined Chiefs of Staff had approved Nimitz’ plan to take the Gilberts and Marshalls.

The New and Improved U.S. Navy

Although the Allied “Defeat Germany First” grand strategy placed significant limitations on the resources that could be allocated to the Pacific, by late 1943 those resources were considerable. The industrial might of the United States, which the late Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto had feared and warned the military leadership in Tokyo about in vain, was already coming to bear. Between the Pearl Harbor attack and the end of 1943, the U.S. navy commissioned seven Essex-class fleet carriers (with another 17 on the way) and nine Independence-class light carriers, quickly built on light cruiser hulls. The Japanese would only be able to commission one new fleet carrier (in mid-1944, just in time to be sunk by a submarine in the Battle of the Philippine Sea), and only three conversions to light carriers. (It should be noted that the Essex carriers completed in 1943 had actually been ordered, and several laid down, prior to Pearl Harbor in anticipation of the outbreak of war). Although the Japanese commissioned two new super-battleships (Yamato and Musashi) after Pearl Harbor, by the end of 1943, the U.S. Navy commissioned six modern battleships, with two more on the way (not counting the cancelled Montana class), plus two that had been commissioned just before Pearl Harbor. By the end of that same year, the Navy also commissioned four heavy cruisers to none for the Japanese, plus 14 light cruisers to only a couple for the Japanese.

Not only were the Japanese about to be overwhelmed by the sheer numbers of U.S. ships and aircraft: The superior U.S. technical and qualitative advantages would quickly become apparent. Although the Japanese were able to equip a handful of ships with radar (and the occasional surprise, such as radar counter-detection gear), by the end of 1943, U.S. ships were festooned with constantly improving air search, surface search and fire control radars, networked into new combat information centers, enabling U.S. commanders to make much better use of their radar advantage, particularly for radar fighter direction and fleet air defense. New U.S. ships, and older ones that had been refitted, were crammed with the new Bofors 40-mm (replacing the jam-prone 1.1-inch guns) and Oerlikon 20-mm anti-aircraft guns (replacing the completely inadequate .50- and .30-caliber machine guns), along with 5-inch/38-caliber dual-purpose guns using radar-proximity (“VT”) fused shells that were deadly to attacking aircraft beyond weapons-release range. (The variable timed—“VT”—nomenclature was actually a cover to hide the carefully guarded secret that the shells were really triggered by miniature radars when in lethal proximity to the target.) Numerous other U.S. innovations included identification friend or foe (IFF) gear, aircraft equipped with 5-inch rockets for ground and ship attack, drag rings to improve aerial torpedo reliability, fog nozzles for fire-fighting hoses, fire-fighting schools for the entire crew, more intricate compartmentation, greatly improved damage control organization and techniques, use of screening vessels as “fire boats,” and many more.

Perhaps most important of all were the new U.S. Navy aircraft, particularly the Grumman F6F Hellcat fighter. Although the Hellcat had the same six .50-caliber machine guns as the older (later model) F4F Wildcat, the Hellcat was 100 to 150 miles per hour faster than the Wildcat, more maneuverable, even tougher, and superior in every way. More importantly, it was superior to anything the Japanese had. In many respects the F4U Corsair was even better than the Hellcat (it was even faster, for example), but initial difficulties with earlier models in landing on a carrier resulted in it being limited to a land-based role until much later in the war. The new SB2U Helldiver dive bomber was an improvement over the SBD Dauntless (20 miles per hour faster), but not as great a leap forward as the Hellcat was to the Wildcat (which was actually because the Dauntless was a darn good plane). The new Grumman TBF (and later General Motors TBM) Avenger torpedo bomber was a great improvement over the TBD Devastator, most of which had been shot down anyway. Nevertheless, it wasn’t until fixes were finally implemented to the unreliable U.S. aerial torpedoes in 1944 that the Avenger began to reach its full potential.

In late 1943, the U.S. Navy’s biggest problem was probably lack of experience. Due to the dramatic expansion of the fleet, the Annapolis graduates who had made up the great preponderance of the officer corps and pilots at the start of the war, and almost exclusively at the senior ranks (and who paid a very high price to hold the line in the dark early days of the war), were now spread thin across the fleet. In the aircraft squadrons, attrition of the early cadre of U.S. pilots had been very high, from both enemy and operational causes, such that by late 1943 the great majority of naval aviators lacked combat experience. By late 1943, almost 75 percent of officers on even veteran ships were reservists or from new commissioning sources other than Annapolis (though these officers would acquit themselves with distinction). As much as 50 percent or more of enlisted manning was by crewmen who had never been to sea before.

However, unlike the Japanese, who kept their best pilots and shipboard officers in the front line until they died, the U.S. Navy rotated the best combat-experienced officers and enlisted back to the States to train others and pass their experience on. As a result, a whole new generation of naval aviators, very few of them Annapolis graduates, would rise to greatness in the latter years of the war, with a similar phenomenon aboard ships. The senior commanders, though, were virtually all Annapolis men to the end. To deal with the experience problem, Admiral Nimitz sent his fast carrier task forces on a series of raids in the fall of 1943, on the principle that the only way to gain combat experience was in combat.

Fast Carrier Strikes, August–October 1943

On 1 September 1943, aircraft from the new Essex-class (27K tons, 90 aircraft) carriers Yorktown (CV-10) and Essex (CV-9), and the new Independence-class (11,000 tons, 45 aircraft) light carrier Independence (CVL-22) under the command of Rear Admiral Charles A. Pownall, struck Marcus Island, which is about 1,500 miles from Midway Island and 1,000 miles from Tokyo. Surprise was achieved and in six strikes of 275 sorties, several Japanese Betty twin-engine bombers were destroyed on the ground, along with other facilities, for the loss of three Hellcat fighters and one Avenger torpedo bomber. This was the first combat use of the new F6F Hellcat fighter.

On 18–19 September, Pownall led a different task group made up the new Essex-class carrier Lexington (CV-16) and new Independence-class light carriers Princeton (CVL-23) and Belleau Wood (CVL-24) in a series of raids on Tarawa and Makin Islands. Incorporating lessons from the Marcus strikes, these attacks were significantly more destructive to shore installations, destroying on the ground nine of the 18 Japanese planes on Tarawa and inflicting substantial casualties on Japanese troops for the loss of four U.S. aircraft. Extremely valuable photo intelligence was also obtained that informed the planning for the Tarawa and Makin landings.

On 5 and 6 October 1943, Rear Admiral Alfred E. Montgomery led Essex (CV-9), Yorktown (CV-10), Lexington (CV-16), Cowpens (CVL-25), Independence (CVL-22), and Belleau Wood (CVL-24) in two days of strikes on Japanese-occupied Wake Island, inflicting substantial damage in six strikes of 738 sorties, although 12 U.S. aircraft were shot down and 14 lost to accidents. Wake was also shelled by U.S. cruisers and destroyers. Twenty-two Japanese planes were destroyed, leaving only 12 left to reinforce the Marshalls. An unintended consequence of the Wake raids was that the Japanese, fearing a landing was imminent, executed all 98 U.S. civilians who had been detained as forced labor on the island when it fell to the Japanese in December 1941. Rear Admiral Sakaibara was tried and hanged after the war for the execution of the civilians.

U.S. carriers Saratoga (CV-3), Princeton (CVL-23), Bunker Hill (CV-17), Essex (CV-9), and Independence (CVL-22) participated in raids on Rabaul in Admiral Halsey’s area on 5 and 11 November 1943, in support of the Bougainville landings (see H-Gram 024 for details.)

One of the innovations of the carrier strikes in the central Pacific, which became standard practice, was to station submarines in “lifeguard” patrols off islands being struck in order to rescue downed aircrew. At the request of Rear Admiral Pownall, the commander of U.S. submarines in the Pacific, Vice Admiral Charles Lockwood, ordered USS Skate (SS-305) to conduct the first such patrol during the Wake Island strikes (rescuing 6 or 7 air crewmen.) Lieutenant j.g. (and future President) George H. W. Bush would have his life saved by just such a lifeguard submarine rescue later in 1944. This practice was a big morale boost to U.S. naval aviators.

Operation Galvanic Forces

On 15 March 1943, the Central Pacific Force was re-designated as the Fifth Fleet, and Vice Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, previously Admiral Nimitz’ Chief of Staff after the Battle of Midway, assumed command on 5 August, 1943. Spruance was generally embarked on the heavy cruiser USS Indianapolis (CA-35). Spruance chose Rear Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner to be the commander of V Amphibious Force (and Rear Admiral Theodore Wilkinson replaced Turner as Commander III Amphibious Force in the Northern Solomon Islands campaign). For Operation Galvanic, Turner flew his flag on the Pearl Harbor–veteran battleship Pennsylvania (BB-34). Major General Holland M. “Howling Mad” Smith, USMC, commanded V Amphibious Corps, in charge of Marine (2nd Marine Division) and Army (165th Regimental Combat Team) operations ashore. Turner divided V Amphibious Force in two. Turner retained overall command, and command of the Northern Attack Force (TF 52), charged with taking Makin Island, as Makin was closer to the major Japanese base at Truk, presumed to be the axis of greatest threat. Spruance, in Indianapolis, operated with the Northern Attack Force for the same reason. Rear Admiral Harry W. Hill was assigned to command the Southern Attack Force (TF 53), with the mission to take Tarawa.

The armada that was about descend on the Gilbert Islands included 191 warships in four task forces: four Essex-class carriers, four Independence-class light carriers, seven smaller escort carriers, thirteen battleships, eight heavy cruisers, over a dozen light cruisers and 70 destroyers and destroyer escorts. The transports and cargo ships were carrying 27,600 assault troops, 7,600 garrison troops, 6,000 vehicles (including the Marine’s new LVT “amphtracs,” later shortened to “amtracs”) and 117,000 tons of cargo, sustained by 13 fleet oilers and 9 merchant oilers, and the ships of another new innovation, the mobile logistics base.

Covering the whole operation was the Fast Carrier Force Pacific Fleet (Task Force 50) commanded by Rear Admiral Pownall, broken down into four Task Groups. TG 50.1, the carrier interceptor group, under Pownall’s direct command, embarked in the carrier Yorktown (CV-10), with Lexington (CV-16), and the light carrier Cowpens (CVL-25), would pound Japanese airfields in the Marshalls commencing 23 November. It was also positioned to intercept any Japanese aircraft from the Marshalls trying to reach Makin or Tarawa, shooting down 17 of 20 that made the attempt the first day, and repeating the performance the next.

Meanwhile, TG 50.4, the relief carrier group, under the command of Rear Admiral Frederick C. Sherman, embarked in the carrier Saratoga with the light carrier Princeton attacked Nauru Island 380 miles west of the Gilberts on 19 Nov, to ensure no Japanese aircraft on Nauru could intervene in the invasion of the Gilberts. TG 50.2 and TG 50.3 provided direct cover to the northern and southern attack groups.

Additional land-based air support was provided by TF 57, commanded by Rear Admiral John H. Hoover, embarked on the seaplane tender Curtiss (AV-4) at Funafuti lagoon, Ellice Islands. Including attached Seventh Army Air Force aircraft, over 100 B-24 Liberator four-engine bombers, 24 PBY Catalina amphibians, and 24 Ventura twin-engine bombers provided pre-invasion bombardment and other support. In September, the USS Ashland (LSD-1), the first of a completely new type of amphibious support ship, landed forces to occupy the uninhabited Baker Island (a U.S. possession), which was 100 miles closer to Tarawa than Funafuti, in order to establish a base to operate eight Navy Liberators of Fleet Air Photographic Squadron Three (VD-3). The squadron was to conduct extensive photo reconnaissance of the Gilberts, and, when Tarawa was captured, stage there to do the same over the Marshalls. In addition to the photo reconnaissance, the submarine Nautilus had conducted 18 days of intelligence collection in late September/early October.

Loss of Submarines USS Corvina (SS-226) and USS Sculpin (SS-191)

The U.S. deployed ten submarines to support Operation Galvanic, with several stationed in the Marshalls and several stationed off Truk, specifically to report and attack any attempt by the Japanese Combined Fleet to react to the U.S. landings in the Gilberts. Two of these submarines, USS Corvina (SS-226) and USS Sculpin (SS-191) were lost to Japanese action.

On 16 Nov 1943, Corvina, commanded by Commander Roderick Rooney, on her first war patrol, was sighted on the surface 85 miles southwest of Truk by Japanese submarine I-176. I-176 fired three torpedoes at Corvina, two of which hit and exploded, sinking Corvina with her entire crew of 82. Corvina was the only U.S. submarine known to have been sunk by a Japanese submarine. According to one account (Wikipedia), Corvina had previously hit I-176 with a torpedo that failed to detonate, but I have been unable to verify that. I-176 had previously hit and seriously damaged the heavy cruiser Chester near Guadalcanal in October 1942, and would later be sunk with all 103 hands on 16 May 1944 off Bougainville by the combined efforts of the destroyers Franks (DD-554), Haggard (DD-555), and Johnston (DD-557). Johnston and her skipper, Commander Ernest Evans, would go on to immortality at the Battle of Leyte Gulf in October 1944.

On 18 November, the submarine Sculpin, on her ninth war patrol, and under the command of Lieutenant Commander Fred Connaway (his first war patrol as commanding officer), patrolling north of Truk, was depth-charged, forced to the surface and sunk by gunfire from the Japanese destroyer Yamagumo. Captain John Philip Cromwell (USNA ’24), on board to coordinate a subsequent U.S. submarine wolfpack attack, chose to go down with the submarine rather than risk revealing to the Japanese under torture his knowledge of the impending Tarawa/Makin operations and his knowledge of “Ultra” code-breaking intelligence. Cromwell would be awarded a posthumous Medal of Honor, the most senior submarine officer to be so recognized, and one of three submarine officers to receive the award posthumously.

In May of 1939, Sculpin had been on her shakedown cruise when she was diverted to search for the lost submarine Squalus (SS-192), and was the first to sight the sunken submarine’s bow still above water. Sculpin establish communications via underwater telephone (until the cable parted) and then via Morse code tapping on Squalus’ hull, thereby determining that survivors were still alive inside the submarine. Sculpin further assisted divers in the rescue operations that saved 33 of Squalus’ crew of 59.

On Sculpin’s second war patrol, on 4 February 1942, she fired three torpedoes at the Japanese destroyer Suzukaze off Sulawesi in the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia). Two of the torpedoes hit resulting in heavy damage and the ship being beached to prevent sinking, in one of the first U.S. submarine successes of the war. Suzukaze was salvaged and repaired, but was later torpedoed and sunk by submarine Skipjack (SS-184) on 25 January 1944, while escorting a convoy from Truk to Eniwetok in the Marshall Islands. (Skipjack would be sunk in the second atomic bomb test at Bikini Atoll, in the Marshalls, then raised and sunk again as target for conventional weapons.)

On Sculpin’s fifth war patrol, she reported hitting the Japanese light cruiser Yura with minor damage on 15 October 1942 and being driven off by the Yura’s gunfire; however, postwar analysis indicated Yura was not hit and suffered no damage. Yura was hit by a torpedo from Grampus (SS-207) on 18 October 1942, which failed to explode and only put a dent in Yura. U.S. aircraft from Guadalcanal finally did the job on Yura on 25 October 1942. Grampus was lost with all hands in March 1943.

On the night of 18-19 November, on her ninth war patrol, with new commanding officer Fred Connaway, Sculpin gained radar contact on a large high-speed convoy (which included the light cruiser Kashima and submarine tender Chogei) and made a fast end run to set up a surface attack in the early morning hours just before dawn. However, Sculpin was forced to dive when she was sighted, and the convoy zigged directly towards her. Sculpin surfaced after the convoy passed; however, the convoy commander had left the destroyer Yamagumo behind in anticipation of Sculpin doing just that, and Sculpin surfaced within 600 yards of the destroyer and was immediately sighted. Sculpin dove while Yamagumo conducted two depth-charge attacks, which inflicted damage and knocked out Sculpin’s depth gauge.

Running low on battery, Sculpin attempted to surface at 1200 in a rain squall, but due to the broken depth gauge, the boat broached and was immediately detected by Yamagumo. Sculpin dived again, but Yamagumo laid a damaging 18 depth-charge pattern, which knocked out Sculpin’s sonar and caused Sculpin to lose depth control and go below safe depth, springing so many leaks and taking on so much water that she had to run at high speed to maintain depth, making her easy for Yamagumo to track.

As it became apparent the boat would probably sink, Connaway opted to surface and attempt to fight it out there. As Sculpin’s crew manned the deck guns, Yamagumo’s first salvo hit the conning tower, killing Connaway, the executive officer, the gunnery officer, the rest of the bridge watch and cutting down the gun crew with shrapnel. At this point, the senior surviving Sculpin officer, Lieutenant George Brown, informed Captain Cromwell he intended to abandon and scuttle the boat. Cromwell concurred, but chose to remain aboard the boat; he and 11 others went down with the Sculpin, while nine were killed topside.

The Yamagumo picked up 42 survivors, but threw one badly wounded Sailor back in the water. The survivors were taken to Truk and interrogated for ten days before being split into two groups to be taken to Japan, 21 aboard the escort carrier Chuyo and 20 aboard the escort carrier Unyo. (Chuyo was one of the carriers that Tunny—SS-282—attacked on 9 April 1943, but got away due to defective torpedoes; see H-Gram 018.)

Chuyo’s luck ran out just after midnight on 4 December 1943, when she was hit by a torpedo from Sailfish (which was actually the Squalus refloated, repaired, and renamed), which blew off her bow and collapsed the forward flight deck. While steaming backwards toward Yokosuka, Chuyo was hit again six hours later in the port engine room by two torpedoes from Sailfish. Chuyo still refused to sink and at 0842, Sailfish boldly attacked yet again, with a Japanese cruiser and destroyer alongside Chuyo, and hit Chuyo with one or two more torpedoes in the port side. This time Chuyo capsized and sank in six minutes, taking 737 passengers and 513 crew to the bottom, along with 20 of the 21 survivors of Sculpin on board. Only George Rocek survived by grabbing the ladder of a passing destroyer and hauling himself on board. The 20 Sculpin survivors on Unyo would finish the war as forced labor in a copper mine. All told, 63 men aboard Sculpin were lost.

Although Chuyo was primarily used as an aircraft ferry, she was technically the first Japanese aircraft carrier sunk by a U.S. submarine in the war, and Sailfish would receive the Presidential Unit Citation and survive all twelve of her war patrols. Yamagumo would be sunk by torpedoes from the destroyer McDermutt (DD-677) on the night of 24–25 October during the Battle of Surigao Strait (and her wreck would be located by the research vessel Petrel in 2017.)

Captain John Philip Cromwell’s Medal of Honor citation:

“For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty as Commander of a Submarine Coordinated Attack Group with Flag in U.S.S. SCULPIN, during the Ninth War Patrol of that vessel in enemy controlled waters off Truk Island, November 19, 1943. Undertaking this patrol prior to the launching of our first large scale offensive in the Pacific, Captain Cromwell, alone of the entire Task Group, possessed secret intelligence information of our submarine strategy and tactics, scheduled fleet movements and specific attack plans. Constantly vigilant and precise in carrying out his secret orders, he moved his undersea flotilla forward despite savage opposition and established a line of submarines to southeastward of the main Japanese stronghold at Truk. Cool and undaunted as the submarine, rocked and battered by Japanese depth charges, sustained terrific battle damage and sank to excessive depth, he authorized SCULPIN to surface and engage the enemy in a gun fight, thereby providing an opportunity for the crew to abandon ship. Determined to sacrifice himself rather than risk capture and subsequent danger of revealing plans under Japanese torture or use of drugs, he stoically remained aboard the mortally wounded vessel as she plunged to her death. Preserving the security of his mission at the cost of his own life, he had served his country as he had served the Navy, with deep integrity and an uncompromising devotion to duty. His great moral courage in the face of certain death adds new luster to the traditions of the United States Naval Service. He gallantly gave his life for his country.”

(In 1954, the Dealey-class destroyer escort USS Cromwell—DE-1014—would be named in his honor, serving until decommissioned in July 1972.)

D-Day, Tarawa, 20 November 1943

Before dawn on 20 November 1943, the Southern Attack Force (TF 53) commanded by Rear Admiral Harry W. Hill, flying his flag on the Pearl Harbor–veteran battleship USS Maryland (BB-46), arrived off Tarawa. TF 53 included three battleships, five escort carriers, five cruisers, 21 destroyers, an LSD and 16 transports, with Major General Julian C. Smith’s 2nd Marine Division embarked. TF 53 was covered by the Southern Carrier Group (TG 50.3), commanded by Rear Admiral Alfred E. Montgomery, embarked in the carrier Essex, with the carrier Bunker Hill and light carrier Independence, back from their 11 November strike on Rabaul. TF 50.3 commenced bombing Tarawa on 18 November. These air raids did considerable damage to Japanese positions, but probably, and more importantly, caused the Japanese to expend a prodigious amount of ammunition, so that when the U.S. assault came, the Japanese were already husbanding scarce ammunition.

Tarawa Atoll was defended by over 4,500 Japanese troops, primarily on the main island of Betio (with the airfield), commanded by Rear Admiral Keiji Shibasaki. The defensive positions on Tarawa were described as “skillfully planned, amply manned and bravely defended.” The intelligence estimate was actually very good: Guns and defensive positions had been accurately plotted by extensive photo reconnaissance from air and submarine, and the troop estimate was accurate to within a hundred. The best enemy troops were the 1,497 naval Infantry of the Sasebo 7th Special Naval Landing Force. The 1,112 troops of the 3rd Special Base Force were also very combat-capable. There were 1,247 troops of the 111th Pioneers (somewhat like Seabees) and an additional 970 in the 4th Fleet Construction Unit, of which half were Korean. These troops were expected and prepared to fight to the death (except the Koreans), and, when the battle was over, only one officer, 16 enlisted personnel, and 129 Koreans had been taken alive.

The biggest factor that would cause things to go so badly on the first day of the landings was that there were no accurate tide tables for Tarawa, as it was prone to unpredictable “dodging tides,” an irregular neap tide that ebbs and flows several times per day at unpredictable intervals and can maintain constant lower levels for many hours. Admiral Turner was aware that on the day of the landing there was significant risk of a low dodging tide that would prevent landing craft from getting over the reef. Much has been made of this; however, based on both weather forecast and climatology, there was also significant risk that conditions for the landing would be even worse had he chosen to delay. Turner knowingly gambled, and in this case the dodging tide won.

At 0430, before dawn on 20 November, the U.S. transports completed lowering boats. At 0441, a red star cluster flare went up from the island, suggesting the Japanese were aware the landing was about to occur. (The Japanese certainly knew that something was up, because the LSTs carrying the LVT amphtracs had to sail ahead of the main invasion force due to their slow speed of 8 knots. These LSTs were discovered and attacked by Japanese aircraft on 18 and 19 November, which were fortunately beaten off by stout anti-aircraft defense.)

At 0505, the destroyer Meade (DD-602) laid a smoke screen on the shore side of the flagship, Maryland, to conceal the flash from a catapult launch of a scout aircraft. The screen apparently failed, as two minutes later Japanese shore batteries opened fire on Maryland, commencing the battle. The Maryland responded and silenced the shore batteries, and continued shelling the island until 0542, in anticipation of the carrier aircraft commencing strikes at 0545. However, due to some foul up, the aircraft weren’t planning to bomb until later, and Maryland’s first salvo had knocked out her own radios, resulting in a coordination challenge. The aircraft did not commence bombing until 0610. In the interim, Japanese batteries resumed firing, straddling the transports Zeilin (APA-3) and Heywood (APA-6) as they were loading Marines into boats 11,000 yards from the beach. Rear Admiral Hill was forced to order the transports to back off, injecting more delay and confusion.

Once the air strikes ended at 0622, the assembled warships (three battleships, four cruisers, and several destroyers) commenced a general bombardment of the island for 80 minutes, which would prove to be not nearly enough. Despite 3,000 tons of projectiles, the flat trajectory of the close-in ships proved to be ineffective against many of the Japanese bunkers, although the shelling did kill large numbers of Japanese troops, destroy guns and positions, and, in particular, knocked out Japanese communications, preventing them from coordinating resistance. However, there was almost a 30-minute gap between the time the bombardment ceased and the time the Marines first hit the beach at the 0830 H-hour. As a result, those Japanese who survived the bombardment were able to re-man their positions and inflict many casualties on the Marines, and would prove particularly lethal to those in the boats that grounded on the reef, making them vulnerable to Japanese fire, and forcing many Marines to wade (and some to drown) several hundred yards to the shore under intense Japanese fire. (Somewhere in this horror was a young Marine named Charles Chalk, my first wife’s father, who would go on to survive Peleliu and Okinawa, too.)

Although the LVT amphtracs were able to make it over the reef (and more than proved their worth during the battle), even their losses were steep, with 90 amphtracs destroyed—35 in deep water as a result Japanese gunfire, and 26 destroyed while crossing the reef, with the loss of over 300 men in the amphtracs.

During the naval bombardment, the minesweepers Pursuit (AM-108) and Requisite (AM-109) swept the channel into the lagoon, and the destroyers Ringgold (DD-500) and Dashiell (DD-659) entered the lagoon to provide fire support to Ashland (LSD-1) and the LSTs (disembarking the LVT amphtracs) and the main Marine landings on the lagoon side of Betio. Ringgold was hit by dud Japanese shells while entering the lagoon, but otherwise the destroyers were able to lay down effective fire without interference. When the two destroyers ran low on ammunition they were relieved by the destroyers Frazier (DD-607) and Anderson (DD-411.)

The battle on Betio was exceptionally bloody. By the end of the first day, of 5,000 Marines that had gotten ashore, 1,500 were dead or wounded. At times the issue was very much in doubt. The commander of the Marines ashore, Colonel David M. Shoup, distinguished himself by rallying attacks under intense fire, for which he would be awarded a Medal of Honor. (Shoup would go on to a distinguished career in World War II and Korea, would become the 22nd Commandant of the Marine Corps during the Kennedy Administration, and, after retiremen,t would emerge as a vocal critic of the Vietnam War and of the strategy being used to attempt to win it.)

Ferocious fighting continued on the second day on Betio as it became obvious that every Japanese intended to fight to the death and the Marines did their best to oblige them. In one incident on 21 November, a rising tide was threatening to drown wounded Marines who had been trapped on the reef. Two Navy salvage crews from the transport Sheridan (APA-51) began a rescue effort. One LCVP landing craft coxswain (who remains unknown to history) displayed extraordinary boat-handling skills, while simultaneously silencing a Japanese machine gun and taking out a sniper. The coxswain rescued 13 wounded Marines, but 35 Marines on the reef who had lost their weapons refused to get on the craft, imploring the coxswain to bring back weapons to fight with.

The original plan for Tarawa assumed that 18,600 assault troops would be able to quickly overrun the island, but it took four days of heavy fighting that cost the lives of 980 Marines and 29 Sailors, with 2,101 wounded, for an island of only a few acres. Recriminations began quickly and lasted decades, as many questioned the purpose and cost for such a small piece of real estate far from everywhere, and the press sensationalized the negative aspects of the operation. Admiral Nimitz would receive mail from bereaved relatives with the theme, “You killed my son on Tarawa for nothing.” Even General Holland M. Smith in an article in the Saturday Evening Post in 1948, and in his book Coral and Brass, claimed that the cost was not worth it and that the U.S. should have leapfrogged directly to Kwajalein in the Marshalls. Nevertheless, extensive lessons were learned on Tarawa: If they had been not learned there, they would have had to be learned the hard way somewhere else. A strong case can be made that a direct assault on Kwajalein, without incorporating the lessons of Tarawa, would have been thrown back into the sea, at least initially.

Admiral Nimitz’ planning officer, Captain James Steel, compiled a document entitled “A Hundred Mistakes Made on Tarawa.” Among these was that the naval bombardment was not long, heavy, or accurate enough (this would be rectified in future landings, but would require radical and rapid innovation in forward ammunition supply). The naval air support of Marines on the ground was also badly flawed. (This would be significantly improved in later operations; however, in addition, General Smith would urge that Marine Corps air wings be formed to operate off of escort carriers, and, later in the war, Marine aircraft would fly from carriers.) The number of amphtracs was far too low, and those deployed had significant operational deficiencies. By the landings at Kwajalein in January 1944, new and redesigned LVT amphtracs would be used. Radios were deficient, especially those on landing craft and ashore (and the ones on battleships didn’t work so well after a broadside either). This would also lead to rapid innovation and improvement. The document also discussed Admiral Turner’s “bad guess” regarding the tides (which only serves to highlight the importance of our Navy’s METOC community today). Although the Intelligence was actually considered good, a lesson of Tarawa was the need for last minute eyes-on pre-landing reconnaissance of tide and beach conditions, and identifying and clearing obstacles, leading to the significant enhancement, mission adjustment, and reallocation of the Navy’s new Underwater Demolition Teams (UDT), which would eventually lead to creation of the Navy SEALS. As a result of the improvements derived from the lessons of Tarawa, Navy historian Rear Admiral Samuel Eliot Morison judged that, “Every man there [Tarawa], lost or maimed, saved at least ten of his countrymen.” Even today, though, the debate continues.

D-Day, Makin Island, 20 November 1943

Before dawn on 20 November, Rear Admiral Turner’s Northern Attack Force (TF 52) and Vice Admiral Spruance in heavy cruiser Indianapolis arrived off Makin Island. TF 52 included the battleships New Mexico (BB-40), Mississippi (BB-41), Idaho (BB-42), and Pennsylvania (BB-34, flagship), three escort carriers, four heavy cruisers, 14 destroyers, and six transports carrying the U.S. Army’s 165th Regimental Combat Team (of the 27th Infantry Division), along with an LSD and three LST’s. TF 52 was covered by the Northern Carrier Group (TG 50.2) commanded by Rear Admiral Arthur W. Radford, embarked in the carrier Enterprise (CV-6), with the light carriers Belleau Wood (CVL-24) and Monterey (CVL-26). TG 50.2 commenced strikes on Makin on 19 November. Of note, Rear Admiral Radford would go on to be four-star VCNO, CINCPACFLT and the second Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (1953–57). Also on board Monterey as assistant navigator, anti-aircraft battery director, and athletic officer was future President of the United States Gerald R. Ford.

The battleship bombardment of Makin Island got off to a bad start with an explosion in the Number 2 14-inch turret on board Mississippi that killed all 43 men in the turret and wounded 19 more. Mississippi had won the gunnery Battle E numerous times and had a reputation as the fastest-firing battleship in the fleet. She would be back in action within two months. However, this was actually the second fatal explosion in Mississippi’s Number 2 turret. The first occurred on 12 June 1924 during gunnery practice off San Pedro, California, when incompletely ejected hot gas in a gun that had just fired ignited powder that caused a flash fire in the turret and asphyxiated all 44 members of the turret crew (and observers). When Mississippi was back in the roadstead, and the turret was entered to remove the dead, one of the other guns was accidentally fired, with the shell narrowly missing the passenger ship Yale, killing four of the response team, and maiming several others.

(The turret captain in the 1924 accident, Lieutenant Junior Grade Thomas E. Zellars, USNA ’21, was found with his hand on the flood-control lever, having closed the doors to the ammunition hoist and flooding the magazine, and saving the ship from a catastrophic explosion with his last act. A plaque in Dahlgren Hall at the Naval Academy, emplaced by his classmates, states, “Flaming death was not as swift as his sense of duty and his will to save his comrades at any cost to himself. His was the spirit that makes the service live.” The Sumner-class destroyer Zellars (DD-777) was named in his honor, earned five battle stars in World War II and Korea, survived a kamikaze hit off Okinawa, and was transferred to the Iranian Navy as Babr in 1973. The original memorial marker to the explosion, which had fallen into disrepair in San Pedro, is now preserved aboard the museum ship Iowa, next to Iowa’s Number 2 turret, in which 47 crewmen were killed in an explosion in April 1989.)

After the morning bombardment, two U.S. destroyers, an LSD, and an LST moved into the lagoon, and commenced a late morning landing from a direction the Japanese had not considered the primary threat. The main landing beaches at Makin were on Butaritari Island, the largest in the atoll. Butaritari was defended by less than 800 Japanese troops under the command of Lieutenant Kurokawa. The best Japanese troops were 284 Special Naval Landing Force (Japanese “marines”) and the rest were mostly aviation and construction troops, including 200 Korean laborers (who generally had no interest in dying for the Japanese if they could help it). Despite being bombed and strafed from the air, and bombarded by battleships, cruisers, and destroyers, and overwhelmed by 6,472 assault troops, the few surviving Japanese troops put up a surprisingly spirited resistance that delayed the Army advance, especially after U.S. and Japanese positions became so intermingled that naval gunfire support was not feasible. A close support strike by Enterprise aircraft resulted in fratricide that killed three soldiers. Nevertheless, the U.S. Army troops prevailed, and, compared to the bloodbath at Tarawa, U.S. Army casualties were relatively light with 64 killed and 150 wounded. The Navy, however, would pay a much higher price for the capture of Makin Island. The capture of Makin would soon put U.S. land-based aircraft within 250 miles of Jaluit and 200 miles of Mili, both Japanese airfields on the southern Marshalls.

Capture of Abemama Island

An adjunct to the landings at Tarawa and Makin was to land Marine Raiders on the small Japanese-occupied island of Abemama in order to conduct reconnaissance in preparation for a follow-on landing. The submarine Nautilus embarked 68 Marines of the 5th Amphibious Reconnaissance Company and ten bomb-disposal engineers. The mission started off badly when the destroyer Ringgold (DD-500) mistook the Nautilus for a Japanese submarine when she was on the surface. With her first salvo, Ringgold hit Nautilus at the base of her conning tower with a 5-inch round. The skipper of the Nautilus, Commander William D. Irvin, immediately took her down deep, but for about two hours was in “dire circumstances,” until her crew was able to get things under control with superb damage control. Nautilus continued on with the mission. After landing on the island, the Marines succeeded in cornering the small Japanese garrison. Instead of attacking, the Marines called in fire support from Nautilus. The next morning, 21 November, the Marines discovered that Nautilus guns had killed 14 Japanese and that the rest had committed suicide, leaving the island in Marine hands without need for the larger landing. Commander Irvin was awarded a Navy Cross for this action.

Japanese Reaction to Operation Galvanic

The simultaneous Allied offensives in New Guinea, Bougainville and the Gilberts, along with the carrier raids, whipsawed the Japanese. The commander in chief of the Japanese Combined Fleet, Admiral Mineichi Koga, was eager to engage in a fleet action with the United States because, like Admiral Yamamoto before him, Koga understood that every day that went by meant that the odds would be increasingly stacked against him with the flood of new U.S. warships and aircraft. What he didn’t understand was that by late 1943, it was already far too late.

Reacting to the U.S. carrier strikes on Wake Island on 5–6 October, and thinking it signaled an invasion attempt, Koga deployed a significant portion of the Combined Fleet from its normal anchorage at Truk Island to Eniwetok Atoll at the western end of the Marshall Islands, only to sit for several weeks with nothing happening, after burning large amounts of increasingly scarce fuel (thanks to U.S. submarines sinking Japanese tankers). Learning from mistakes at Midway (lack of reconnaissance), a Japanese submarine, capable of carrying a float plane, was ordered to launch an aerial reconnaissance mission to Pearl Harbor, which, in fact, reported on 17 October that most U.S. ships were missing (both plane and sub got away). However, it wasn’t until the 19th and 20th (D-day) that the Japanese figured out that the Gilberts were the objective. By then, the Japanese force, including the super-battleships Yamato and Musashi (9 x 18-inch guns), the battleships Nagato, Fuso, Kongo, and Haruna, four heavy cruisers, five light cruisers, three destroyer squadrons and 18 submarines were back at Truk. Worse, the Japanese had stripped 27 aircraft from the Marshalls on 12 November to participate in Operation Ro in the northern Solomons, leaving only 46 planes in the Gilberts and Marshalls to defend against the U.S. fast carrier task groups.

The first Japanese air counterattack to the landings at Tarawa and Makin happened quickly. On the evening of 20 November, 16 torpedo bombers from the Marshalls attacked Rear Admiral Montgomery’s carriers (TG 50.3), which were operating about 30 miles west of Tarawa. Nine of the bombers got through the fighters and split into three groups of three. Three attacked the carrier Bunker Hill (CV-17) and were all shot down by anti-aircraft fire. However, the other two groups boxed in the light carrier Independence (CVL-22) and launched five torpedoes. Despite evasive maneuvering, Independence was hit by one torpedo, resulting in flooding of the after engine room, fireroom, and magazine, with 17 crew killed and 43 wounded; she would be out of action until July 1944. All but one of the Japanese planes was shot down.

The Japanese deployed nine submarines in an attempt to counter the landings at Tarawa and Makin. Two of the submarines, RO-38 and I-40, departed Truk and were never heard from again; the causes of their loss are still unknown. On 22 November, the destroyer Meade (DD-602) detected Japanese submarine I-35 on sonar near Tarawa. Meade made a depth charge attack, but lost contact. Destroyer Frazier (DD-607) regained contact, and made two depth charge attacks. Meade rolled back in and depth-charged the sub, which was forced to the surface broadside to Frazier. Both destroyers opened up on the sub with 5-inch and 40-mm guns, and Frazier rammed her just aft of her conning tower. I-35’s crew attempted to man her deck guns, but small-arms fire from Frazier prevented them. When Frazier backed off, the submarine sank stern first, and aircraft dropped more depth charges on her for good measure. Frazier then put a whaleboat in the water to attempt rescue of four survivors, one of which fired on the rescuers and was killed. While the whaleboat was returning to Frazier with the three Japanese, a U.S. aircraft from the escort carrier Suwannee (CVE-27) misidentified the boat and bombed it. Somewhat miraculously it survived a very near miss. Frazier, in turn, fired on the U.S. plane, hitting it twice, but fortunately not shooting it down.

Japanese attempts to strike the landing forces by air continued, but all daylight attempts were beaten back by aircraft from carrier Lexington (CV-16) and light carrier Cowpens (CVL-25). During the course of the landings, no Japanese aircraft were able to attack U.S. forces on Makin Island, and only two minor strikes got through to Tarawa, on 23 November. The Japanese belatedly reinforced the Marshall Islands with carrier aircraft that had just been withdrawn from Rabaul due to high losses in Operation Ro, along with additional bomber aircraft from Truk.

Loss of USS Liscome Bay (CVE-65), 24 November 1943

On 24 November 1943, the escort carrier Liscome Bay was operating about 20 nautical miles southwest of Makin Island. Liscome Bay was the flagship of Rear Admiral Henry Mullinnix, commander of Task Group 52.3, a force of three escort carriers. Liscome Bay, Coral Sea (CVE-57, later renamed Anzio), and Corregidor (CVE-58) were tasked with providing air support to ground operations on Makin and anti-submarine support to U.S. ships in the area. The three escort carriers were operating within a temporary task group, designated TG 52.13, commanded by Rear Admiral Robert M. Griffin, embarked in the battleship New Mexico (BB-40).

Liscome Bay was a Casablanca-class escort carrier, a class of 50 commissioned during the war that were the first escort carriers designed and built from the keel up for the role. (Older classes had been built on converted merchant ship hulls.) The class was designed and built rapidly, and had significant survivability design flaws; five of the class would be lost during the war. Liscome Bay was new, having been commissioned in August 1943, and was under the command of Captain Irving Day Wiltse, who had been the navigator on the carrier Yorktown (CV-5) when she was sunk at the Battle of Midway in June 1942. The ship embarked Composite Squadron 39 (VC-39), initially with 12 FM2 Wildcat fighters (trained for ground attack) and 16 TBM-1C Avenger torpedo bombers (trained for bombing and anti-submarine warfare) under the command of Lieutenant Commander Marshall U. Beebe.

VC-39 was a case study in how dangerous carrier operations were even without the enemy. After leaving Pearl Harbor, one Wildcat crashed, killing the pilot. During the Makin landings, one Avenger crashed in the water and another was lost in an emergency landing. One Wildcat was so badly damaged in a barrier crash that it was cannibalized for parts. On 23 November, five Wildcats got lost and had to make night recoveries; three recovered safely on carrier Lexington (CV-16) and two recovered safely on Yorktown (CV-10,) but the fifth crashed into parked aircraft on Yorktown. The pilot survived but five of Yorktown’s crew did not.

Before dawn, TG 52.13 was steaming in a circular formation with Liscome Bay in the center. The old battleships New Mexico and Mississippi, and the new heavy cruiser Baltimore (CA-68) were to the left, and Coral Sea and Corregidor to the right, with an outer circular screen of five destroyers. At 0400, the destroyer Hull (DD-350) was detached for operations at Makin, and at 0435 the destroyer Franks (DD-554) was dispatched to investigate a dim light (a fading flare dropped by a Japanese aircraft). This left a gap in the formation’s outer screen. New Mexico detected a radar contact at 6 nautical miles and closing, which was then lost, and no evasive action was taken. The contact was probably the Japanese submarine I-175, commanded by Lieutenant Commander Sumano Tabata, which had arrived off Makin the day before.

At 0450, Liscome Bay went to flight quarters, and, at 0505, to general quarters, preparing to launch 13 planes, including one on the catapult, all fueled and armed. The remaining seven planes were in the hanger and were armed but not fueled. As the formation turned into the wind to launch aircraft, I-175 was in the perfect position to take advantage of the gap in the outer screen. The sub remained submerged and fired four bow torpedoes based on sound, and then immediately went deep. None of the destroyers ever saw the submarine, although they dropped 34 depth charges, six of which were close. Two of I-175’s torpedoes narrowly missed Coral Sea.

An officer on Liscome Bay sighted a torpedo approaching from starboard only moments before impact at 0513 just aft of the after engine room. The explosion of the torpedo immediately detonated the poorly protected bomb storage magazine (one of the design flaws) that was stocked with almost a full allowance of 200,000 pounds of bombs. The resulting explosion was so massive that it was seen on ships many miles away: Shrapnel hit destroyers at 5,000 yards and the battleship New Mexico at 1,500 yards was showered by metal, clothing, and body parts. More than one third of the after end of Liscome Bay was obliterated and everyone aft of the forward bulkhead of the after engine room was killed. All steam, compressed air, and fireman pressure was immediately lost, large parts of the flight deck were destroyed, and the hangar deck engulfed in flames. Of 39 aircrew in the planes on deck, 14 were killed. It was obvious that the ship could not be saved, and within 23 minutes she rolled to starboard and sank.

Like many World War II losses, the exact number of crewmen killed as a result of the sinking of Liscome Bay may never be known, as it was difficult to track wounded who may have died later. Of the 272 (55 officers and 217 enlisted personnel) recorded as being rescued, many were grievously burned and maimed. Initial casualty reports listed 642 (51 officers and 591 enlisted men), while other accounts list a total of 644 killed. The Navy Department War Damage Report lists 54 officers and 648 enlisted men killed (702 total), which may include those who died from wounds.

Among the dead was the task group commander, Rear Admiral Mullinix, and Cook Third Class Doris Miller, the first African-American to be awarded a Navy Cross (for his actions during the Pearl Harbor attack). The ship’s commanding officer, Captain Wiltse, was last observed walking into a mass of flames and never seen again. A number of aerographer’s mates, who had survived the sinking of the Wasp (CV-7) in September 1942 were lost, although one survived both sinkings. Liscome Bay suffered the highest percentage of casualties (over 70 percent) of any U.S. aircraft carrier in World War II.

Among the survivors was VC-39 commanding officer, Lieutenant Commander Beebe, who would go on to distinguished service in World war II (as a “double ace”—10.5 kills—and a Navy Cross recipient) and Korea (where he would be the inspiration for James Michener’s book The Bridges at Toko-Ri, which was dedicated to Beebe). Admiral Mullinnix’ chief of staff, Captain John G. Crommelin also survived. Crommelin was the oldest of five brothers who all graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy and served in the war. Two of them were killed, and two, including John, would reach flag rank after the war. The Perry-class frigate Crommelin (FFG-37) was named in honor of the five brothers (and was sunk as a RIMPAC target in 2016, where she didn’t go down easy).

I-175 would be sunk with all 100 hands on 4 February 1944 during Battle for Kwajalein, when destroyer Charrette (DD-581) and destroyer escort Fair (DE-35) engaged her, and Fair fired a hedgehog depth charge pattern that sank the submarine.

(Sources for this section include, Navy Department Bureau of Ships War Damage Report No. 45, dated 10 March 1944, “USS LISCOMBE BAY, Loss in Action, Gilbert Islands, Central Pacific, 24 Nov 1943” and “USS Liscome Bay Hit by a Torpedo Near Makin I During WWII,” by William B. Allmon in the July 1992 edition of World War II magazine.)

Loss of Rear Admiral Henry Maston Mullinnix

Rear Admiral Henry M. Mullinnix was the fourth of five U.S. Navy flag officers to be killed as a result of enemy action in World War II, cutting short an extremely promising career begun when he graduated first in his class of 177 as the five-stripe regimental commander (highest midshipman rank at the time) in the U.S. Naval Academy class of 1916 (and he played varsity football, too). After initially serving in destroyers deployed to Queenstown for European anti-submarine operations, he became one of the Navy’s early aviators. Among other things he was credited with being responsible for the development of the air-cooled engine for naval aircraft. He rose through the aviation ranks to become commanding officer of USS Saratoga (CV-3), before being selected for rear admiral (at age 51, possibly the youngest ever at that time) and given command of the three escort carriers of Carrier Division 24, which formed TG 53.2, supporting the landings on Makin Island.

Embarked on Liscome Bay, Mullinnix was in Air Ops when the torpedo from I-175 struck and caused the massive catastrophic explosion that sank the ship on 24 November. Some accounts say he was last seen sitting with his head in his hands, possibly badly wounded. Other accounts say he was last seen in the water. Either way, he did not survive. Navy historian Samuel Eliot Morison wrote in the dedication to Volume VI of the History of U.S. Naval Operations in World War II, “Admiral Mullinix, one of the most gifted, widely experienced and beloved of the Navy’s ‘air admirals’…He died just as the air arm of the Navy, to which he devoted the second half of his life, was coming into the fullness of its power and glory.”

Rear Admiral Mullinnix would be awarded a posthumous Legion of Merit with Combat V:

The President of the United States takes pride in presenting the Legion of Merit (posthumously) to Rear Admiral Henry Maston Mullinnix, United States Navy, for exceptionally meritorious conduct in the performance of outstanding services to the Government of the United States as Commander of a carrier air support group during the assault on Makin Atoll during World War II. Admiral Mullinnix skillfully conducted anti-submarine and combat air patrols supporting our landing operations. Through his brilliant leadership, escort carriers were able to carry out a well-coordinated attack against the Japanese.

The Forrest Sherman-class Mullinnix (DD-944), which served from 1957 to 1983, was named in his honor. (Of note, his name is misspelled with one “n” in Memorial Hall at the U.S. Naval Academy, and regretfully, I managed to misspell it as well in the last H-gram.)

Loss of Cook Third Class Doris Miller

As noted above, one of the sailors lost in the sinking of Liscome Bay (CVE-65) was Cook Third Class Doris Miller, who had been the first African American to be awarded the Navy Cross for his heroism in combat aboard the battleship West Virginia (BB-48) during the attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941. Miller’s highly publicized award made him the first real hero of the African American community in the United States during the war, and his loss came as a profound shock. I have found no account that describes how Miller met his ultimate fate, other than that he was one of the 591 (at least) enlisted men lost when Liscome Bay was torpedoed by a Japanese submarine, exploded, and rapidly sank on 24 November 1942 near Makin Island during Operation Galvanic.

Doris Miller enlisted in the U.S. Navy on 16 September 1939 into the messman branch, the only branch open to him as an African American. The messman branch was racially segregated and comprised primarily of Black and Filipino personnel; White sailors were not permitted to serve in the messman branch. Conversely, Blacks sailors were not allowed to serve in almost all other ratings, since with the conversion of Navy ships to oil, “coal passer” was no longer an option.

The messman branch was responsible for feeding and serving officers, who at the time were all White. (The all-White commissary branch cooked for the enlisted crew.) At the time, messmen could advance from mess attendant third class to second class to first class and then branch to officer’s cook third class or steward third class up to chief officer’s cook or chief steward. In February 1943, the messman branch was changed to the steward branch. Mess attendants became steward’s mates, and the “officer’s” was dropped from the cook titles (although the duties remained the same). In June 1944, new rating badges were introduced to cooks and stewards that had petty officer and chief chevrons. However, despite the rating badges, even chief cooks and chief stewards ranked below petty officer third class. It was not until 1950 that cooks and stewards were accorded petty officer status.

How messmen, cooks, and stewards were used in battle depended to a degree on where in the country the ship’s commanding officer was from. In general, most had battle stations that involved significant manual labor, such as ammunition handling or stretcher bearing, and a number of others assisted in first aid stations. On some ships, however, they were given more responsibility. For example, on the submarine Cobia (SS-245) the skipper held a competition among the crew to find the best gunners to man and operate the deck gun. Cobia’s two Black stewards won the competition, and when the submarine went to surface battle stations, the Black stewards manned the deck gun. Nevertheless, Cobia’s action reports treat the fact that Black sailors manned the deck gun as almost an embarrassing secret, but at least the skipper put combat capability ahead of racial prejudice.

After enlisting, Miller was first assigned to the ammunition ship, Pyro (AE-1), but on 2 January 1940 he reported to the battleship West Virginia, where he quickly became the ship’s heavyweight boxing champion. He was promoted to mess attendant second class on 16 February 1941. In July 1941, he had temporary duty on the battleship Nevada (BB-36) for secondary battery gunnery school, returning to West Virginia in August. On the battleships, the secondary battery was comprised of 5-inch guns, some in protected locations for surface action, and some on deck for antiaircraft (or surface action) defense.

On 7 December 1941, Miller had finished serving breakfast and was collecting laundry when the attack began. In the first minutes of the attack, West Virginia was hit by at least five torpedoes (and later by two bombs). When Miller got to his battle station in the ammunition magazine for the amidships antiaircraft battery, it had already been destroyed by a torpedo hit.

As West Virginia was sinking—only quick counter-flooding kept her from capsizing like Oklahoma (BB-37)—Miller reported to a location on the ship known as “Times Square” to make himself available for duty. The ship’s communications officer, Lieutenant Commander Doir C. Johnson, ordered Miller to accompany him to the bridge to assist in moving West Virginia’s commanding officer, Captain Mervyn Bennion, to a less exposed location. Bennion had been on the bridge when he was hit and severely wounded by shrapnel from a bomb that hit Tennessee (BB-43), which was nested inboard of West Virginia. Bennion’s wound would prove mortal, but he continued to issue commands to defend the ship, despite having his abdomen sliced open. Miller and another sailor moved Bennion behind the conning tower for better protection, but Bennion insisted on remaining on the bridge, although he was fading rapidly.

At this point, Lieutenant Frederic H. White ordered Miller to help Ensign Victor Delano load the unmanned No. 1 and No. 2 .50-caliber antiaircraft machine guns. (The operational ships at Pearl Harbor were actually at Condition Baker (equivalent to Condition III—wartime steaming) readiness with a quarter of their antiaircraft guns manned and ready before the attack.) White gave Miller quick instruction on how to feed ammunition to the machine guns, but after a momentary distraction, White turned to see Miller already firing at Japanese aircraft, so White wound up feeding the ammo to Miller and Delano (on the other gun).

Various accounts give different numbers on how many planes Miller shot down. The reality is that there is no way of knowing as by then antiaircraft fire was so intense from all the ships that it is not possible to determine exactly which gun shot down which plane, and some more recent accounts have become embellished. The problem with the .50 calibers was that they were completely ineffective against aircraft before the weapons release point; the best they could do was keep an attacking aircraft from coming back a second time. Nevertheless, Miller and Delano fired until they were out of ammunition.

At this point, Lieutenant Claude V. Rickets (the first seaman to rise via the United States Naval Academy to four-star rank, and who was responsible for ordering the counterflooding that saved West Virginia from capsizing), ordered Miller and Signalman A. A. Siewart to carry the now only partially conscious Captain Bennion up to the navigation bridge to get him out of the smoke pouring into the bridge, but Bennion died soon after. Miller then helped move numerous other injured sailors as the ship was ordered abandoned due to her own fires and flaming oil floating down from the destroyed Arizona (BB-39). West Virginia would lose 105 killed out of her crew of 1500. Captain Bennion would be awarded a posthumous Medal of Honor.

Following the attack, Miller was transferred to the heavy cruiser Indianapolis (CA-35) on 15 December 1941. On 1 January 1942, the Navy released a list of commendations for 7 December, including a commendation for an “unnamed Negro.” The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) asked President Franklin D. Roosevelt to award the Distinguished Service Cross (which wasn’t a Navy medal) to the unnamed Black sailor, and the recommendation was routed to the Navy Awards Board. In the meantime, Lawrence Reddick, the director of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem, was able to discover Miller’s name, which was then published in the African American newspaper the Pittsburgh Courier and then by the Associated Press on 12 March 1942.

In response to public pressure, Senator James Mead (D-NY) and Representative John D. Dingell Sr. (D-MI) introduced Senate and House resolutions to award Miller the Medal of Honor. The Navy responded with a letter of commendation signed by Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox (who was not known for racially progressive views). This ignited an extensive writing campaign by numerous Black organizations to convince Congress that Miller should be awarded the Medal of Honor, and the National Negro Congress denounced Knox for recommending against it.

Unlike Knox, Chief of Naval Operations Ernest J. King at least saw the importance of having the Black community’s support for the war effort. (During the war, over one million Black workers would be employed in defense industries, including six hundred thousand Black women.) On 11 May 1942, President Roosevelt approved the award of the Navy Cross to Miller, the first for an African American. At the time, the Navy Cross was third in the order of precedence, after the Medal of Honor and Distinguished Service Medal, but was moved to second precedence in August 1942.

On 27 May 1942, Admiral Chester Nimitz, commander in chief of the Pacific Fleet, personally presented the Navy Cross to Miller in a ceremony with other awardees on the flight deck of Enterprise (CV-6) in Pearl Harbor. Nimitz stated, “This marks the first time in this conflict that such high tribute has been made in the Pacific Fleet to a member of his race and I’m sure that the future will see others similarly honored for brave acts.”

The Navy Cross Citation for Mess Attendant Second Class Doris Miller is as follows:

For distinguished devotion to duty, extraordinary courage and disregard for his own personal safety during the attack on the Fleet in Pearl Harbor, Territory of Hawaii, by Japanese forces on December 7, 1941. While at the side of his Captain on the bridge, Miller, despite enemy and strafing and bombing and in the face of a serious fire, assisted in moving his Captain, who had been mortally wounded, to a place of greater safety, and later manned and operated a machine gun directed at enemy Japanese attacking aircraft until ordered to leave the bridge.

Miller was promoted to mess attendant first class on 1 June 1942. As the first Black hero of the war, there was intense pressure to bring Miller back to the United States for war bond tours, to which the Navy was slow to respond, resulting in editorial comments in the press like “Navy felt Miller too important waiting tables in the Pacific.” On 23 November 1942, while still assigned to Indianapolis, Miller was brought back to the states for multiple speaking engagements on a short war bond tour.

After returning to Indianapolis, Miller was promoted to cook third class (under the renamed steward branch) and on 1 June 1943 reported to the escort carrier Liscome Bay. On 7 December 1943, Miller’s parents were informed that he was missing in action. He would never be found. The Knox-class frigate Miller (FF-1091), commissioned on 30 June 1973, was named in Doris Miller’s honor and would serve until decommissioned in October 1991.

It should be noted that during the Civil War at least seven Black sailors were awarded the Medal of Honor, at a time when the enlisted ranks in the Navy were integrated (which was true up until the Wilson administration implemented segregation in the federal government, including in the Navy). The Navy Cross was not created until 1919 (retroactive to World War I), so the Medal of Honor was the only medal for valor at the time of the Civil War, and standards were different. Nevertheless, the Medals of Honor awarded to Black sailors were for courage in serious battles, including four awarded for the Battle of Mobile Bay.

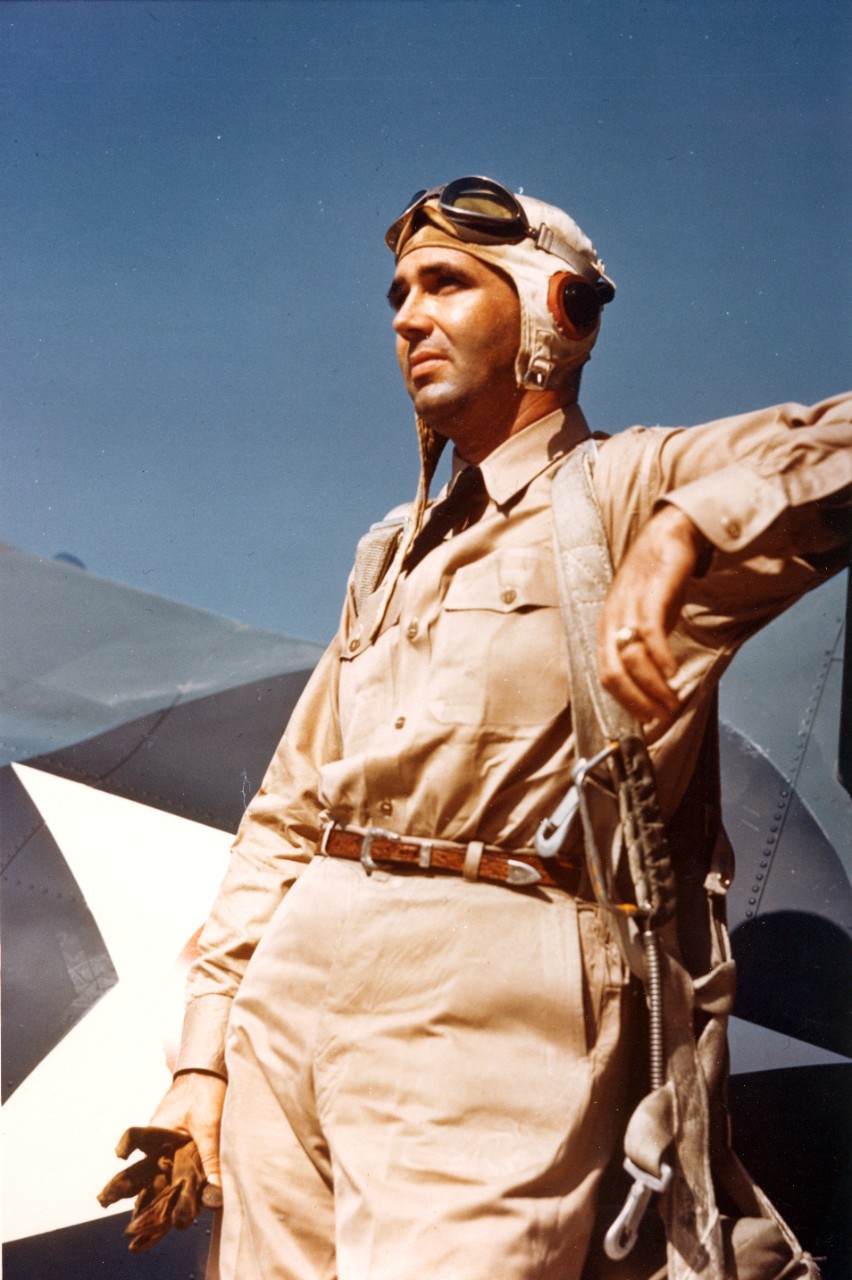

Loss of Medal of Honor Recipient Lieutenant Commander Butch O’Hare

After sundown on 26 November 1943, the U.S. Navy attempted the first carrier-based night fighter intercept operations. The fighters were launched in response to continuing night attacks by Japanese land-based twin-engine Betty torpedo bombers (which had previously hit and damaged the light carrier Independence. During the mission, the commander of Enterprise Air Group, Lieutenant Commander Edward H. “Butch” O’Hare, was shot down, and neither his aircraft or body were ever found. O’Hare had previously been awarded the Medal of Honor for single-handedly downing several Japanese Betty torpedo bombers attempting to strike the aircraft carrier Lexington (CV-2) on 20 February 1942, making him the first naval aviator to be awarded the Medal of Honor in World War II. This also made him an instant national hero at a time when the nation needed one in the dark days after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Like the loss of Doris Miller on Liscome Bay, the loss of Butch O’Hare was a shock to the American public. For many years, there was uncertainty as to whether he was shot down in the darkness by “friendly fire” from another Navy aircraft or whether he was shot down by the Japanese. The analysis that I find most compelling indicates that he was hit and downed by a lucky shot from one of the Betty bombers.

O’Hare came from a colorful background. At the time O’Hare was seeking to enter the U.S. Naval Academy, his father was a lawyer working for mobster Al Capone, but who turned on Capone providing key evidence leading to the gangster’s conviction on tax evasion, and was rewarded for his efforts by being gunned down in a mob hit in November 1939. Despite this, O’Hare graduated from the Naval Academy in 1937 and finished aviation training in May 1940, reporting to Fighter Squadron 3 (VF-3), where future “ace” Lieutenant John S. “Jimmy” Thach was executive officer. Thach quickly recognized O’Hare’s talent, especially at gunnery. When Saratoga (CV-3) was torpedoed and damaged by a Japanese submarine on 11 January 1942, VF-3 transferred to Lexington, replacing her obsolete F2A Brewster Buffalo squadron, and was re-designated VF-2. Thach led one section and future ace (and four-star) Noel Gayler led the other.

On 20 February 1942, Task Force 11, centered on Lexington, was approaching the Japanese base of Rabaul (which had yet to develop the formidable air defenses seen in 1943), but was detected by a Japanese flying boat while still 450 miles away. At 1112, Thach and another pilot shot down the four- engine Kawanishi H6K4 Type 97 Mavis at 43 nautical miles from the carrier, but not before the plane had radioed a report. At 1202, two other Lexington fighters shot down a second Mavis, while a third radar contact turned away. The Japanese wasted no time in launching a two-group 17-plane strikeof G4M Betty medium torpedo bombers. Unfortunately for the Japanese, no torpedoes or fighters had arrived at Rabaul yet, so the Bettys carried only bombs, and launched with no fighter escort.

At 1542, Lexington radar detected the incoming strike at long range, but lost the contact. At 1625, radar re-acquired the incoming strike at 47 nautical miles and closing fast, which turned out to be nine Bettys. Fighters were vectored to intercept and additional fighters were launched, including O’Hare (flying F4F BuNo. 4031 “White 15”), but O’Hare and his wingman Marion “Duff” Dufilho were held overhead as the Bettys were engaged and five were shot down. Four of the Betty’s dropped bombs on Lexington, but missed by 3,000 yards. The surviving Bettys were pursued and shot down, although two Wildcats were shot down by the Bettys’ lethal tail guns. One of the Bettys was actually shot down by an SBD Dauntless dive bomber on ASW patrol.

However, at 1649, Lexington radar detected a second formation of Bettys approaching from the disengaged side at a range of only 12 nautical miles. The situation was critical as seven Wildcats were pursuing the remnants of the other formation of Bettys in the opposite direction, while five were orbiting, waiting to recover and low on fuel. O’Hare and Dufilho were vectored toward the new threat and intercepted the incoming Bettys (reported as nine, but actually eight) at 9 nautical miles from the carrier. Dufilho’s guns jammed and O’Hare attacked alone. (Early models of the Wildcat mounted four .50-caliber machine guns with 450 rounds per gun, which amounted to about 34 seconds of firing time.)

On his first firing pass, using a deflection technique he had developed (which kept him out of the envelope of the 20-mm cannon in the Betty’s tail position), O’Hare hit the two trailing Bettys, knocking them out of formation, one of them on fire. However, the crew of the burning Betty was able to extinguish the fire, and, unbeknownst to O’Hare, both Bettys were able to catch up and rejoin the formation before the weapons release point. On his second firing pass, O’Hare hit two Bettys in a trailing “V” formation, one of which crashed in flames while the other dumped its bombs and aborted.

As the Betty’s approached their bomb release point, O’Hare made his third firing pass, shooting down the leader of the trailing “V,” and then shooting down the plane of the Japanese mission commander, Lieutenant Commander Takuzo Ito. O’Hare made a fourth firing pass on what was actually one of the planes that had caught up, but ran out of ammunition. As Ito’s command plane was falling, his command pilot, Warrant Officer Chuzo Watanabe, attempted to crash the flaming plane into Lexington, but missed. The four surviving Bettys dropped ten 250-kilogram bombs on Lexington, but missed, this time by only 100 feet. Of the 17 Betty bombers, only two made it back to Rabaul, both damaged by O’Hare.