Pearl Harbor Attack

7 December 1941

USS Arizona (BB-39) ablaze, immediately following the explosion of her forward magazines, 7 December 1941. Frame clipped from a color motion picture taken from onboard USS Solace (AH-5) (80-G-K-13512).

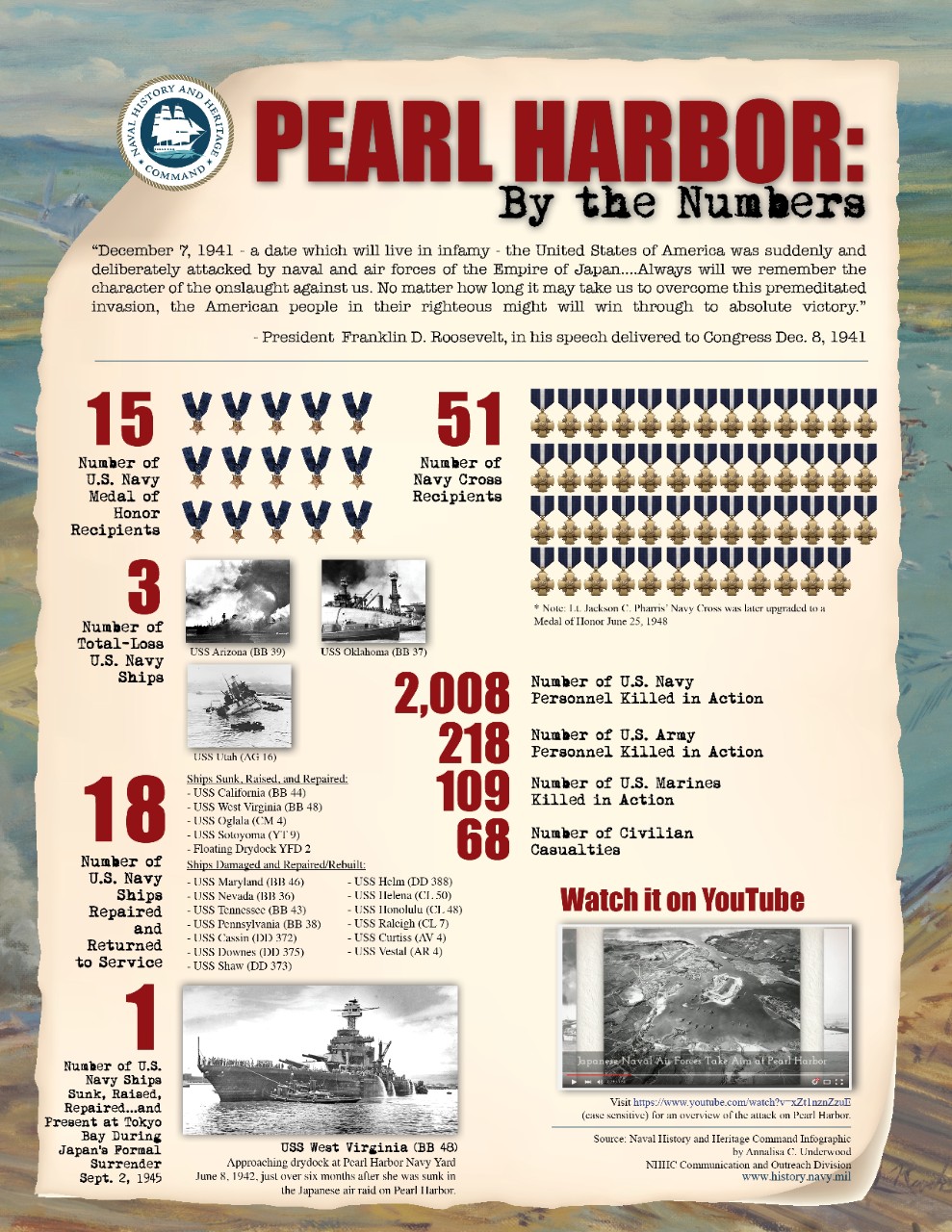

World War II came to the United States of America on Sunday morning, 7 December 1941, with a massive surprise attack by the Imperial Japanese Navy. "Like a thunderclap from a clear sky," Japanese carrier attack planes (in both torpedo and high-level bombing roles) and bombers, supported by fighters, numbering 353 aircraft from six aircraft carriers, attacked the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor in two waves, as well as nearby naval and military airfields and bases. The enemy sank five battleships and damaged three; and sank a gunnery training ship and three destroyers, damaged a heavy cruiser, three light cruisers, two destroyers, two seaplane tenders, two repair ships and a destroyer tender. Navy, Army, and Marine Corps facilities suffered varying degrees of damage, while 188 Navy, Marine Corps, and U.S. Army Air Force planes were destroyed. Casualties amounted to: killed or missing: Navy, 2,008; Marine Corps, 109; Army, 218; civilian, 68; and wounded: Navy, 710; Marine Corps, 69; Army, 364; civilian, 35. Japanese losses amounted to fewer than 100 men and 29 planes.

Sailors, Marines, and Soldiers fought back with extraordinary courage, often at the sacrifice of their own lives. Those without weapons to fight took great risk to save wounded comrades and to save their ships. Pilots took off to engage Japanese aircraft despite the overwhelming odds. Countless acts of valor went unrecorded, as many witnesses died in the attack. Fifteen U.S. Navy personnel were awarded the Medal of Honor — ranging from seaman to rear admiral — for acts of courage above and beyond the call of duty, ten of them posthumously.

Among the Sailors recognized with our nation's highest award for valor were Chief Water Tender Peter Tomich onboard the ex-battleship Utah, who sacrificed his life to prevent the boilers from exploding, enabling boiler room crews to escape before the ship capsized. Another was Chief Boatswain Edwin J. Hill, who cast off the lines as the battleship Nevada got underway, swam through the burning oil to get back on board his ship, where he was killed by Japanese strafing after being credited with saving the lives of many junior Sailors. Ensign Francis Flaherty and Seaman First Class J. Richard Ward, onboard the battleship Oklahoma, sacrificed their lives to enable turret crews to escape before the ship capsized. Onboard the battleship California, Chief Radioman Thomas J. Reeves, Machinist's Mate First Class Robert R. Scott and Ensign Herbert C. Jones stayed at their posts at the cost of their lives to keep power and ammunition flowing to the antiaircraft guns as long as possible. Rear Admiral Isaac C. Kidd and Captain Franklin Van Valkenburgh onboard the battleship Arizona, and Captain Mervyn S. Bennion onboard the battleship West Virginia directed the defense of their ships under heavy fire, until the ships were sunk and they were killed.

Japanese forces were astonished at the quick reaction and intensity of U.S. antiaircraft fire. That more Japanese aircraft were not shot down had nothing to do with the skill, training, or bravery of our Sailors and other servicemembers. Rather, U.S. antiaircraft weapons were inadequate in number and capability, for not only had the Japanese achieved tactical surprise, they achieved technological surprise with aircraft and weapons far better than anticipated — a lesson in the danger of underestimating the enemy that resonates to this day.

While damage to the U.S. Pacific Fleet's battleline proved extensive, it was not complete. The attack failed to damage any American aircraft carriers, which had been providentially absent from the harbor. Our aircraft carriers, along with supporting cruisers and destroyers and fleet oilers, proved crucial in the coming months. The Japanese focus on ships and planes spared our fuel tank farms, naval yard repair facilities, and the submarine base, all of which proved vital for the tactical operations that originated at Pearl Harbor in the ensuing months and played a key role in the Allied victory. American technological skill raised and repaired all but three of the ships sunk or damaged at Pearl Harbor. Most importantly, the shock and anger that Americans felt in the wake of the attack on Pearl Harbor united the nation and was translated into a collective commitment to victory in World War II.

Remembrance Resources

Resources for Pearl Harbor remembrance events may be found in our Pearl Harbor Remembrance section.

Two Pearl Harbor Medals for Valor Awarded in 2017

- Background: Navy Awards Two Medals for Valor at Pearl Harbor

- Silver Star: LTJG Aloysius H. Schmitt, CHC, USN

- Bronze Star: BMC Joseph L. George, USN

Imagery

- Photography

- Story map outlining the attack on Pearl Harbor

People

- Oral Histories

- Survivor Reports

- Biography of Doris Miller

- U.S. Marines at Pearl Harbor

- Navy Medical Activities at Pearl Harbor

- In Memoriam: Lieutenant Louis A. Conter, USN (Ret.) The Last Living Survivor of USS Arizona (BB-39), by Sam Cox (Rear Adm. USN, Ret.), Director, Naval History and Heritage Command

Ships

History of the Base

- Building the Navy's Bases [For Pearl Harbor, please see chapter XXII (page 121)]

- Pearl Harbor Submarine Base: 1918-1945

- Historic Manuscript: U.S. Navy and Hawaii

Communications Intelligence

Why Pearl Harbor?

In the video sound bite below, Naval History and Heritage Command historian Robert J. Cressman discusses Japan's strategic objective for the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Click the links below for additional sets of video sound bites to hear Cressman answer questions about other aspects of the attack. Videos may be downloaded from DVIDS.

Remembering Pearl Harbor

- Valor in the Pacific [PDF, 84.3 MB; traveling exhibit from the National Museum of the U.S. Navy]

- Ships Commemorating Sailors for Their Actions at Pearl Harbor

- Lesson Plans from the U.S. Navy Museum

Additional Reading

- Pearl Harbor: Why, How, Fleet Salvage and Final Appraisal [by Vice Admiral Homer N. Wallin, USN (Ret.), 1968]

- Disaster in the Pacific [Chapter 26 of The War at Sea 1939-1945, by Captain S.W. Roskill, Royal Navy]

- Pearl Harbor Salvage Report 1944

The Navy Department Library Online Reading Room contains an overview of the Pearl Harbor attack; that page also provides most of the links given above.