Battles of Java Sea and Sunda Strait

27–28 February and 28 February–1 March 1942

Between 20 November 1941 and January 1942, the Striking Force—Task Force Five (TF-5)—submarines, several auxiliaries and long-range patrol aircraft of the U.S. Asiatic Fleet, based at Cavite, Philippines, was ordered to deploy toward the southern islands of the archipelago and the Celebes Sea. This dispersion left little defensive coverage for Manila Bay and amphibious landing areas on Luzon and Mindanao. In part, Japanese landings in the Philippines in December 1941 were successful due to the lack of significant naval and air threats. However, the move southward temporarily preserved the fleet’s most potent combatants (cruisers, destroyers, submarines) for further operations against the enemy. Ultimately, TF-5 and the other Asiatic Fleet units formed part of the naval component of ABDACOM (the combined American-British-Dutch-Australian Command), activated on 15 January 1942 to deny the Japanese access to the Indian Ocean via the so-called Malay Barrier.

Although the U.S. Navy’s initial order of battle under ABDACOM appeared impressive (1 heavy, 2 light cruisers; 13 destroyers; 2 minesweepers; 25 submarines;10 auxiliaries; 28 long-range amphibious patrol aircraft) its actual operational effectiveness was undercut by a variety of factors. Many of the U.S. surface vessels dated back to the World War I era; all were inadequately armed to counter air attacks effectively. Their voyage from Philippine waters to ports in Borneo, Java, and Australia was conducted under constant danger of Japanese bombers, which caused damage to a number of them. Subsequently, Japanese air superiority also dictated a wide dispersion of ABDACOM forces, further impeding an ad-hoc command structure already handicapped by supply limitations, lack of common communication systems, and differing training and execution of operations.

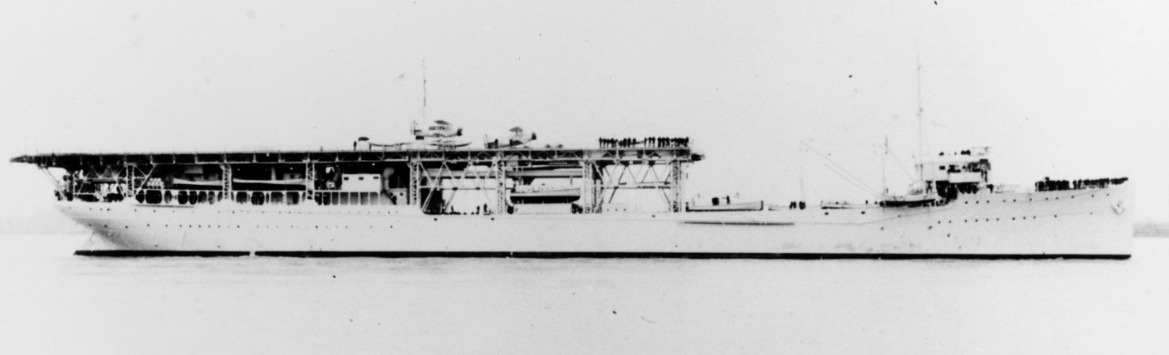

Typical of this difficult period are the fates of USS Langley (AV-3) and USS Peary (DD-226).

Langley, a converted collier that was the Navy’s first operational aircraft carrier (CV-1), was converted to a seaplane tender and redesignated AV-3 in February 1937. Transferred to the Asiatic Fleet in 1939, she supported Naval patrol aircraft during the Pacific neutrality patrols conducted in 1940/41. After departing Cavite on 8 December 1941—the first day of Japanese air attacks on the Philippines—Langley proceeded to Darwin, Australia. She was initially employed in support of Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) antisubmarine patrols and then assigned to ABDACOM. On 27 February 1942, while ferrying sorely needed fighter aircraft from Australia to the Dutch East Indies, Langley sustained heavy damage in a Japanese air attack south of Tjilatjap, Java. Aviation fuel fires broke out on the packed flight deck, steering was impaired, and the ship assumed a 10-degree list. Langley became dead in the water after engineering spaces flooded. After rescuing her crew, escorting destroyers scuttled her with shellfire and torpedoes. This dramatic sequence was captured on film by a crewmember of USS Whipple (DD-217):

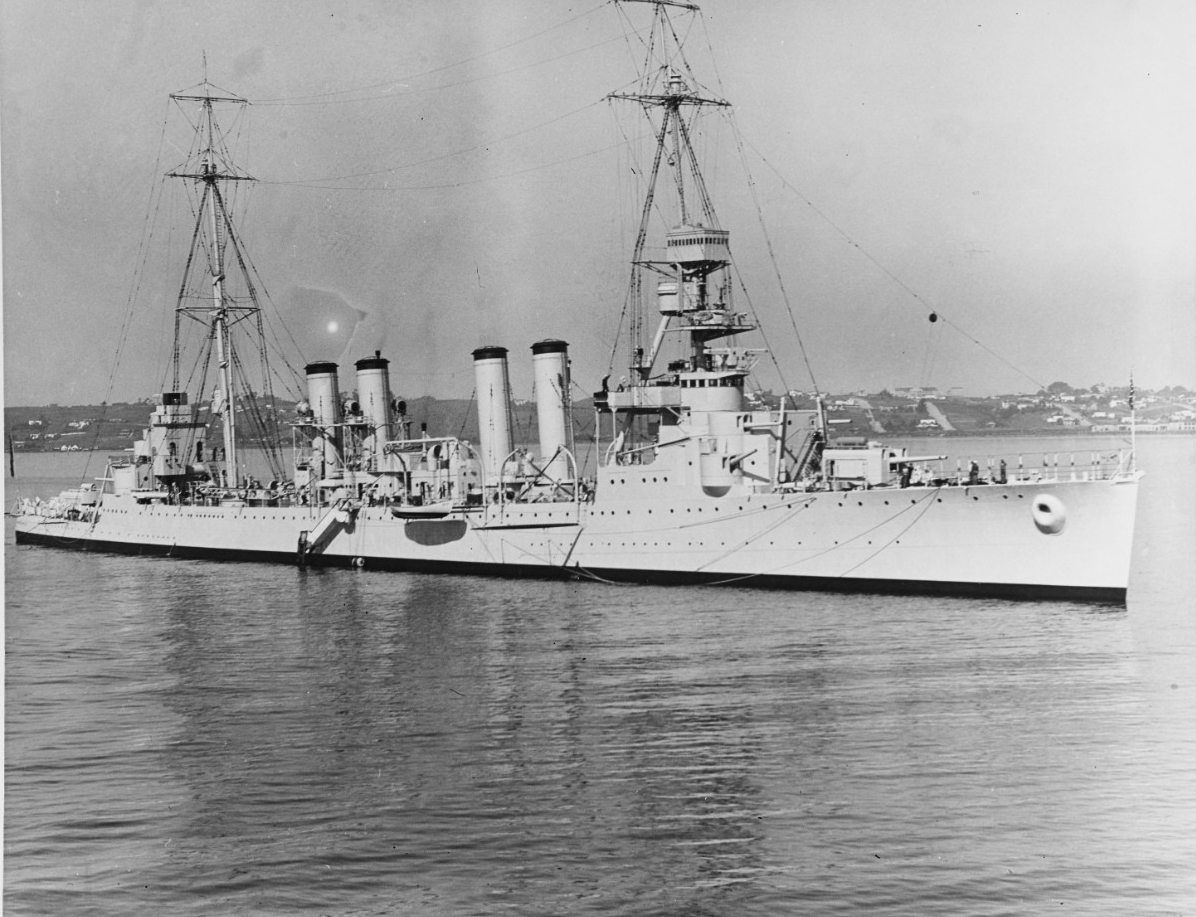

Although Peary was launched in April 1920, she was constructed on the basis of a World War I–era design: flush-decked and with four stacks—a classic “fourpiper.”

Peary was transferred to the Asiatic Fleet in 1921 and initially served on the Yangtze River Patrol. At the advent of World War II, Peary was approaching obsolescence. On 8 December 1941, she was in port at Cavite Navy Yard undergoing maintenance. Two days later, when the base was largely destroyed by a Japanese air attack, Peary sustained a direct bomb hit forward, with eight crewmembers killed in action. Peary was towed out of her berth and away from the fires raging pierside. Following rudimentary repairs, the destroyer initially operated in Manila Bay and then was directed south, evading another air attack on 26 December. On 28 December, Peary was underway through the Celebes Sea toward the Makassar Strait when she was spotted by Japanese air patrols and then subjected to an intense bombing and aerial torpedo attack, which she survived unscathed through adroit maneuvering. She reached Darwin on New Year’s Day 1942. Peary was engaged in antisubmarine patrols into that February. On 19 February, during a mid-morning Japanese air raid on the Darwin, Peary was in port and was attacked by Japanese dive bombers. Their first bomb exploded on the fantail; the second, an incendiary, in the galley deck house; the third did not explode; the fourth hit forward and set off the forward ammunition magazines; the fifth, another incendiary, exploded in the after engine room. The destroyer sank stern first at about 1300 local time. Of Peary’s 120-member crew, 80 were killed and 13 wounded; the ship’s gunnery officer, a lieutenant, was the most senior survivor.

Despite minor tactical victories such as the destruction of six Japanese transports off of Balikpapan, Borneo, by U.S. Navy destroyers on 24 January, the combined Allied naval component was never effectively deployed, in part due to starkly differing interpretations of their mission among the four Allied contingents and to the prevailing uncertainty about Japan’s further operational intent. Admiral Thomas C. Hart, the commander of the U.S. Asiatic Fleet, did his utmost to convince his counterparts of the necessity to both conserve and concentrate their forces for a decisive blow against the enemy, but was overruled. By the time he was relieved on 4 February, his command had been disestablished and its assets and functions nominally transferred to U.S. Naval Forces Southwest Pacific. With the surrender of British forces in Singapore on the 15th, all of Malaya was lost to the Japanese, providing the enemy another springboard for attacks on, and eventual conquest of, the Dutch East Indies. Thus, by mid-February 1942, the situation ABDACOM faced was grim.

Of the U.S. Navy’s three largest in-theater units—Houston (CA-30), Marblehead (CL-12), and Boise (CL-47)—only Houston remained with ABDACOM. Boise had struck an uncharted shoal in the Sape Strait on 21 January and had to retire to Colombo, Ceylon. On 4 February, hoping to repeat the minor triumph at Balikpapan days earlier, the Dutch commander of the combined striking force sortied from Surabaya, Java. Once at sea, the task force came under repeated, concentrated Japanese air attack. Houston’s number 3 (after) turret was hit and put out of action. Marblehead was hit hard in same attack, which caused underwater damage to her bow and subsequent flooding, fires throughout the ship, and a temporarily jammed rudder. She also had to withdraw to Ceylon.

A number of inconclusive surface operations against Japanese forces poised to invade the Dutch East Indies followed. On 27 February 1942, the remnants of the ABDACOM striking force attempted to counter a major invasion fleet approaching Java. In the battle that followed, the Allied ships fought valiantly, but were doomed by lack of air cover and unresolved communication difficulties. The battle was the largest surface action since Jutland in 1916. The Allied and Japanese fleets fought intermittently for seven hours before ABDACOM was defeated—a testament to the determination and bravery of sailors on both sides of the struggle. By the following day, only Houston and the Australian light cruiser HMAS Perth survived.

On 28 February, the two ships steamed into Banten Bay on Java’s northern coast, hoping to damage the Japanese invasion forces assembled there. Houston and Perth sank one transport and forced three others to beach. However, a Japanese destroyer squadron blocked Sunda Strait, the Allied ships’ means of retreat, and enemy cruisers approached from their seaward side. Perth was sunk from gunfire and torpedo hits. Houston fought on alone against overwhelming odds, but was handicapped by the bomb damage inflicted previously to her number 3 turret. Soon after midnight she was struck by a torpedo and began to lose headway. She scored hits on three different destroyers and sank a minesweeper, but suffered three more torpedo explosions in quick succession. An hour later, she sank, her ensign still flying.

Houston's fate was not known by the world for almost nine months, and the full story of her courageous fight was not fully told until after the war was over and her survivors were liberated from Japanese prison camps. The Medal of Honor was posthumously awarded to Houston’s commanding officer, Captain Albert H. Rooks, for extraordinary heroism.

The NHHC essay The Last Battle of USS Houston provides additional details of the Sunda Strait engagement.

In 1943, a since-declassified analysis of the battles by the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) was published. Note that at the time a number of important details of the actions were not yet known. The publication can be found in the Navy Department Library Online Reading Room. NHHC republished the combat narrative with an introduction from NHHC Director Cox in February 2017 in observance of the 75th anniversary; this 75th anniversary edition is also available from the Online Reading Room.

The Online Reading Room also includes period U.S. Navy press releases noting the battles.

Interestingly, Japanese wartime estimates of ABDACOM strengths and intentions were often uncertain. Post-war prisoner-of-war interrogations covering this aspect of the Japanese invasion of the Dutch East Indies confirmed this.

The Naval History and Heritage Command’s blog, The Sextant, features extensive coverage of many aspects of the battles and the command has produced a commemorative video focusing on the last actions of USS Houston.

For the perspective of NHHC Director Samuel Cox, please see H-Gram 003 in which he discusses the U.S. Asiatic Fleet and the first months of war in the Pacific.

Sources:

Robert J. Cressman, The Official Chronology of the U.S. Navy in World War II. Annapolis, MD/Washington, DC: Naval Institute Press/Naval Historical Center, 1999.

Samuel Eliot Morison, History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, Vol. III—The Rising Sun in the Pacific, 1931–April 1942. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1950.