Homeward Bound – World War II Ends in the Pacific

American military planners in the summer of 1945 envisioned a truly formidable task as they prepared for the assault into the Japanese home islands that fall. In combination, Operations Olympic and Coronet, the invasions scheduled respectively for Kyushu that fall and Honshu in early 1946, were projected to produce perhaps a quarter-million or more casualties and dwarf the numbers of men lost in early campaigns. Therefore, waves of relief and joy followed in the wake upon hearing on 14 August 1945 that the Japanese government finally had signed its acceptance of unconditional surrender.

At 7 p.m. in Washington, D.C., President Harry S. Truman broadcast a formal announcement of the long-awaited event over the radio and declared 15 and 16 August to be days of celebration. Sitting just feet away as the president spoke, Fleet Admiral William D. Leahy considered the moment appropriate for solemnly reflecting upon all that the country and world had just endured for so many years. Instead, car horns blared long into the night in the nation’s capital. Across the country in Seattle, mass hysteria erupted. In New York’s Times Square and other crowded cities, Sailors kissed strangers. Hugs, shouts, and more continued the following day as the United States, United Kingdom, and other Allies celebrated victory over Japan and the end of World War II.[1]

Alongside the celebratory mood, however, came a sobering awareness for some of the question, “What next?” In World War II the common American sentiment was, “We are all in this together.” But now the unifying effect of fighting treacherous enemies had been removed and soon, too, would the great economic engine of wartime production.[2] A generation prior, following the end of World War I, a brief but sharp economic downturn accompanied by strikes and race riots unsettled many cities in the immediate postwar years. Now, orders for ships, planes, and tanks, which already had been scaling back since 1944, would dwindle to a relative trickle. Overseas, a new strategic situation quickly was taking shape.

Millions of battered or displaced people now lived or roamed atop the battered and cracked foundations of the European colonial and former Japanese imperial territories. Manila, many coastal Chinese cities, and other locales exposed to fighting had suffered extensive damage. Local leaders of all stripes and abilities maneuvered to attain political power by making nationalist, communist, anti-communist, or other appeals to the masses. Meanwhile, the United States, Soviet Union, and weakened colonial powers of France, the United Kingdom, and The Netherlands hoped to advance their own political and economic interests. Whereas the war had produced enormous, existential challenges that generally could be faced with moral clarity, now peace seemed to introduce a variety of complex and often morally ambiguous problems overseas.

A Range of Reactions

News of the victory over Japan generated a variety of thoughts and emotions for Sailors in the Pacific. For many, an announcement had seemed imminent, although not certain, ever since the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings on 6 and 9 August. Writing to his parents in Ohio, Aviation Machinist's Mate Charles W. “Bill” Cooper noted in a letter dated 10 August, “The news looks pretty bright now with Russia in and the U.S. using their new bomb.” Three days later, which also happened to be his twenty-first birthday, he wrote, “The war can’t last much longer at the rate the Japs are taking it now. You bet your last dollar however that until they actually give up the war is not won.” Following a pause that may indicate his immediate state of mind upon learning the war was over, Cooper resumed his correspondence home on 22 August. “Since I wrote last the Japs have surrender[ed] or are about to. It doesn’t seem possible that the last country opposing us has finally given in. For the first couple of days everyone was drunk with excitement until the Navy came out with a point system for discharge. Under the present system I will be eligible for a discharge in three years and one month.” Continuing with what was a prominent topic to discuss in letters to and from home—the point system—Wright added a common interservice comparison: “Just about everyone thought that the Navy would have at least a fair system and benefit some from the mistakes the Army [made] with theirs.”[3]

Also writing to his parents on 22 August, Pharmacist's Mate James T. Wright reacted more along the lines preferred by Fleet Admiral Leahy. “According to the radio; it looks as if the Jap war is over. McArthur (sic) is going to dictate the terms within the next few days. It seems funny; but none of the fellows are overjoyed; not that they want the war to last; but they are just so numb from a series of emotional shocks that they don’t show any visible elation over anything.”[4] Four days earlier, uncertainty about the surrender dynamics also appeared in a letter Wright’s Aunt Mary had written to her nephew. “Hurrah for VJ Day, when it finally come[s] . . . We can scarcely believe that our prayers will soon be answered and that you boys will be home soon! We’re hoping for Christmas? How do you stack up on points? Just to be back to the U.S.A will be glorious, won’t it? I just know that you have been like so many other millions, mighty tired of your part of the job.”[5]

While the great majority of Sailors and loved ones back home surely felt joy and entertained thoughts of pending reunion following V-J Day, the reality was that much immediate work remained for hundreds of thousands of Sailors and other service members. To facilitate the arrival of Allied (primarily American) occupation forces, minesweepers had to clear enormous quantities of mines that the U.S. had emplaced to strangle Japanese shipping. Some 2.25 million Japanese soldiers and civilians had to be demobilized in the home islands. Millions of chemical munitions had to be disposed. American prisoners of war required medical care and evacuation. The Navy also assisted with sending Korean, Chinese, and other regional nations’ prisoners back home as well as transporting Japanese troops back to their home islands—at its peak repatriating 193,000 people per week.[6] The war also still required an official closing.

The World’s Greatest War Ends

Eighteen days elapsed between Japan’s announcement of capitulation on 14 August and the formal surrender ceremony that occurred on deck the battleship Missouri (BB-63) on 2 September.[7] U.S. leaders as well as some Japanese political counterparts wanted to ensure that Japanese forces quickly understood and accepted that they had been defeated and must now cooperate with their former enemy. At General MacArthur’s direction, Japanese representatives flew to Manilla to receive the specific terms for capitulating. American representatives initially expected the first American forces to enter Japan on 23 August, but they accommodated a Japanese request for additional time to ensure compliance. American paratroopers began securing Atsugui Airfield southwest of Tokyo on 26 August, and minesweepers began clearing Tokyo Bay on 28 August.

Accompanied by escorts, hospital ship Benevolence (AH-13) entered the bay the next day and began caring for Allied prisoners of war. That same afternoon, 29 August, Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz also reached the bay via a Coronado flying boat that subsequently taxied alongside South Dakota (BB-57) so that the Commander in Chief Pacific Fleet could board. Meanwhile, a massive U.S. armada as well as Allied ships steadily filed in and crowded the waters offshore Tokyo and in view of Mount Fuji.[8]

On the momentous morning of 2 September 1945, some 255 Allied ships and boats had assembled as American and Allied representatives gathered aboard Missouri, symbolic of President Truman’s home state. Fleet Admiral Nimitz arrived at 0805 and General of the Army Douglass MacArthur boarded at 0843. The Japanese delegation was transported from Yokohama to the American battleship aboard Lansdowne (DD-486), and the eleven men ascended the starboard gangway at 0856. Minutes later, General MacArthur opened the ceremony with a brief speech and proclaimed, “It is my earnest hope—indeed the hope of all mankind—that from this solemn occasion a better world shall emerge out of the blood and carnage of the past, a world founded upon faith and understanding, a world dedicated to the dignity of man and the fulfillment of his most cherished wish for freedom, tolerance and justice.” Then Japanese Foreign Minister Mamoru Shigemitsu signed the instrument of surrender on behalf of the Japanese government and General Yoshijiro Umezu for the Imperial General Headquarters. Representing the combined Allied Powers, General MacArthur signed acceptance of the surrender, and was then followed by Admiral Nimitz signing for the United States, and representatives of eight Allies. At 0925 General MacArthur concluded the brief ceremony by offering a benediction and declaring “these proceedings are now closed” just prior to an overflight by some 1,000 Army, Air Force, and Navy aircraft.[9] In the United States, meanwhile, President Truman's radio broadcast on the evening of 1 September acknowledged the tremendous sacrifice and contributions made from the whole nation—service members and civilians; men and women; workers, farmers, and businessmen—and its "gallant Allies," and proclaimed 2 September as Victory over Japan Day.[10]

Following the V-J Day announcement and the formal surrender ceremony, most service members not immediately engaged in occupation or stabilization duties had more time to think about home and when they might get there. As referenced in letters above, the point system for determining eligibility for release from the military was on many Sailors’ and their family members’ minds. Some questioned whether it was fair to send home a father or older man with little to no time in combat before releasing a younger, single Sailor who had served in harm’s way for years. Sailors also assessed their own lot relative to that of others in sister services, or in the Navy but stationed stateside. After noting that the Army seemed to be releasing Soldiers quickly, just three weeks into September, and stating his wish that “the Navy would speed up their system of discharging,” Aviation Machinist's Mate Cooper acknowledged, however, that there were positives about still serving overseas some three weeks after the surrender. “I wouldn’t mind staying out here until time for discharge because I am making 70% extra and no one bothers us.”[11]

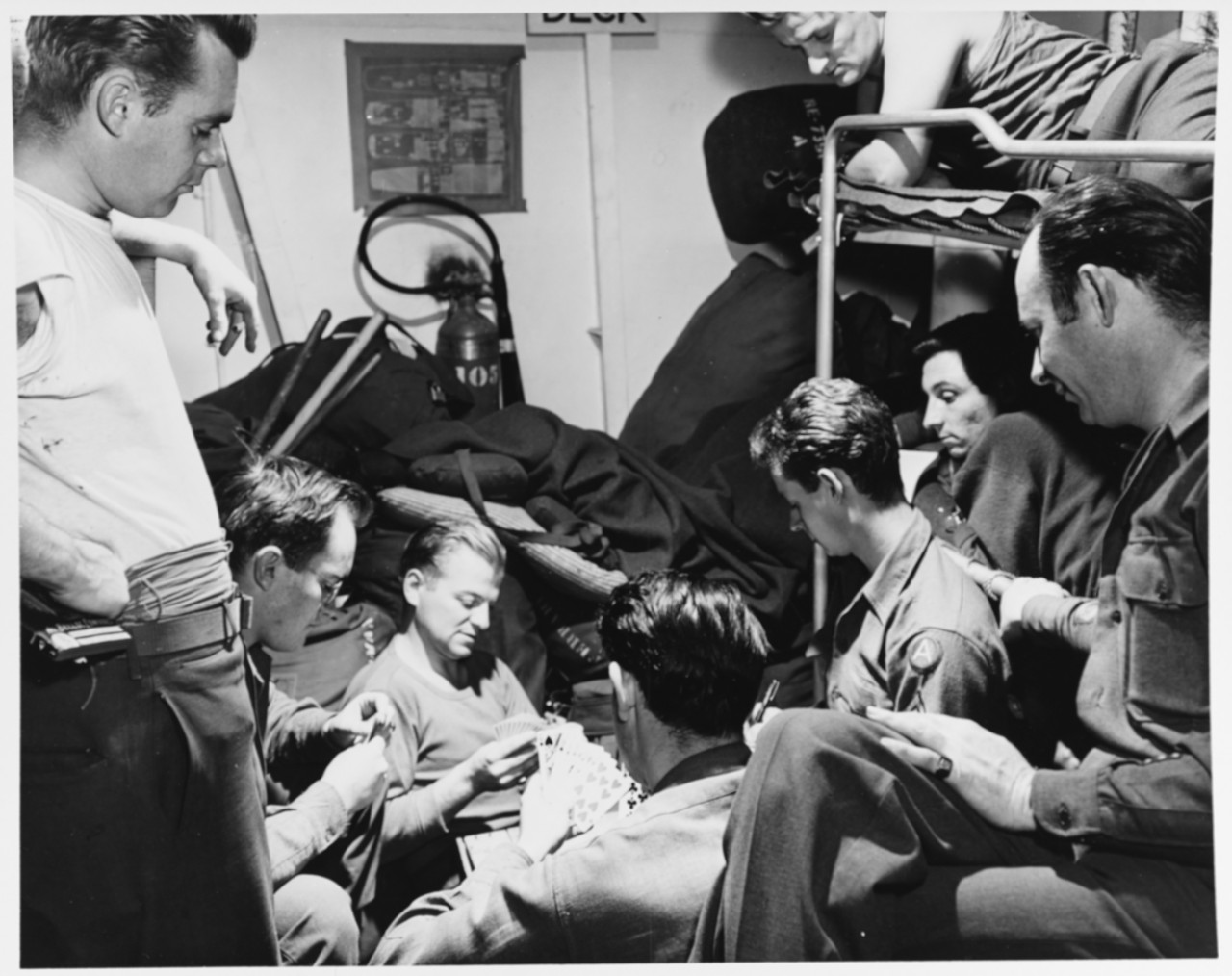

Sailors engaged in a variety of activities to pass the time. Pharmacist's Mate Wright read dozens of novels and sometimes enjoyed current feature films. While enthusiasm for writing seems to have depended upon the individual, most Sailors appreciated when many censorship restrictions were lifted at the end of the war. Finally, they could share more interesting and exciting stories. At the end of an eight-page letter, Wright added a postscript: “How do you like these long letters? It certainly feels good to speak freely again!”[12]

Problems with the processing of mail received regular commentary. In a letter written to his parents on 2 October, Wright noted that, “Our mail was all fouled up because someone had checked our draft as ‘shipped’ and our mail has been forwarded to S.F. [San Francisco] to await our arrival.” Later in the same letter, he mentions receiving old letters from the middle of August because “someone up at Base 3 saved them out rather than forward them [to the stateside reception station] so I got them.”[13] While misdirected mail might take months to reach the attended addressee, especially if a Sailor had relocated a couple times, mail commonly could be delivered in one-and-a-half to two weeks. The military’s use of “V-mail” facilitated the delivery of great quantities of mail from home.

Although many Sailors had extra time on their hands, ship captains and shore commanders aimed to assign enough work and enforce discipline to prevent “idle hands” from being tempted into trouble or drifting into complacency. They assigned ship maintenance jobs and plane overhaul assignments. Many areas aboard needed paint, and nighttime watches still needed to be performed. Sailors, whether in Japan or in more remote areas, were permitted some interaction with locals, but they had to abide by rules. “I am restricted to the ship for a month,” noted Bill Cooper, “because I forgot to turn in my liberty card after going to Yoksuka[sic] yesterday.”[14]

The United States had opted to focus mostly inward after World War I, but in 1945 it chose to take the lead role in shaping international affairs. The country directed some of its vast resources and military power toward stabilizing war-torn areas, shaped new organizations such as the International Monetary Fund, and hosted the newly formed United Nations. What this internationalist approach meant in September 1945 for Sailors such as then-Lieutenant Elmo R. Zumwalt, Jr. was plenty of continuing challenges. Just days after the formal surrender, Zumwalt sailed from Okinawa aboard Robinson (DD-562), which led a dozen minesweepers to clear mines from the approaches to Shanghai. Shortly after arriving in China, he was put in charge of a prize ship, the Japanese 1200-ton river gunboat, HIJMS Ataka. Drawing from his deep well of resourceful and bold thinking, Zumwalt not only completed his military duties with aplomb but also successfully proposed to a twenty-three-year-old whose family departed Russia following the Bolshevik Revolution. The epilogue to this, Zumwalt’s “favorite war story,” is that his marriage to Mouza would reinforce their mutual commitment to service for the next fifty-four years until the Admiral’s passing on 2 January 2000.[15]

While positive stories were the norm, there were also tragic accounts that sprang from the war’s conclusion. Vice Admiral John S. McCain, who led Task Force 38 fast attack carriers for Admiral Halsey in 1945 and was with the Third Fleet commander at the surrender ceremony in Tokyo Bay, flew to San Diego three days later for some long-overdue leave at his home in Coronado. In the middle of a large homecoming party on 6 September, however, McCain fell ill and soon died with his wife at his side. According to the Navy physician, “complete fatigue resulting from the strain of the last four months of combat” had produced a fatal heart attack.[16] A different form of tragedy, sadly, had to be experienced over several years by the families that learned on 11 August that their service member had been declared “missing in action” after not returning from a bombing raid launched from Guam on 26 July. Two years later, in March 1948, they learned that their loved ones had been executed as prisoners.[17]

Fortunately, most Sailors and their families back home found that delays and changes proved the two most difficult types of updates they would receive between the war’s end and reunion. Nearly everyone probably had experienced and overcome at least minor setbacks during the war years, so a sense of commonality and perspective helped maintain most everyone’s spirits. Eventually a ship home would indeed set sail. As the capitalization and punctuation Pharmacist's Mate Wright uses in his brief letter on 20 October 1945 suggests, the news could seem miraculous.

MIRACLES DO HAPPEN! A SHIP HAS COME FOR US! I’M UNCLE SUGAR BOUND!

DON’T EXPECT ME TOO SOON, AS WE’RE STOPPING AT SOME OTHER ISLANDS ALONG THE WAY! IT IS IMPOSSIBLE FOR ME TO BE IN THE U.S. BEFORE NOVEMEBER 10th. DON’T EXPECT ANY MORE MAIL FROM THE “BEAUTIFUL SOUTH SEAS.” LOVE – JIM[18]

In preparation for their planned invasion of the Japanese main islands, American forces had steadily increased their numbers in the western Pacific with ground, sea, and air elements relocating there from Europe and the United States during the spring and summer of 1945. As late as 13 August, President Truman directed General George C. Marshall, Army Chief of Staff, to continue with the planned offensive against Japan.[19] Then official word came the next day that Japan would accept the conditions for surrender. With the war over, most of the Sailors and other service members staging in the Pacific now could shift their thoughts from waging war to returning home.

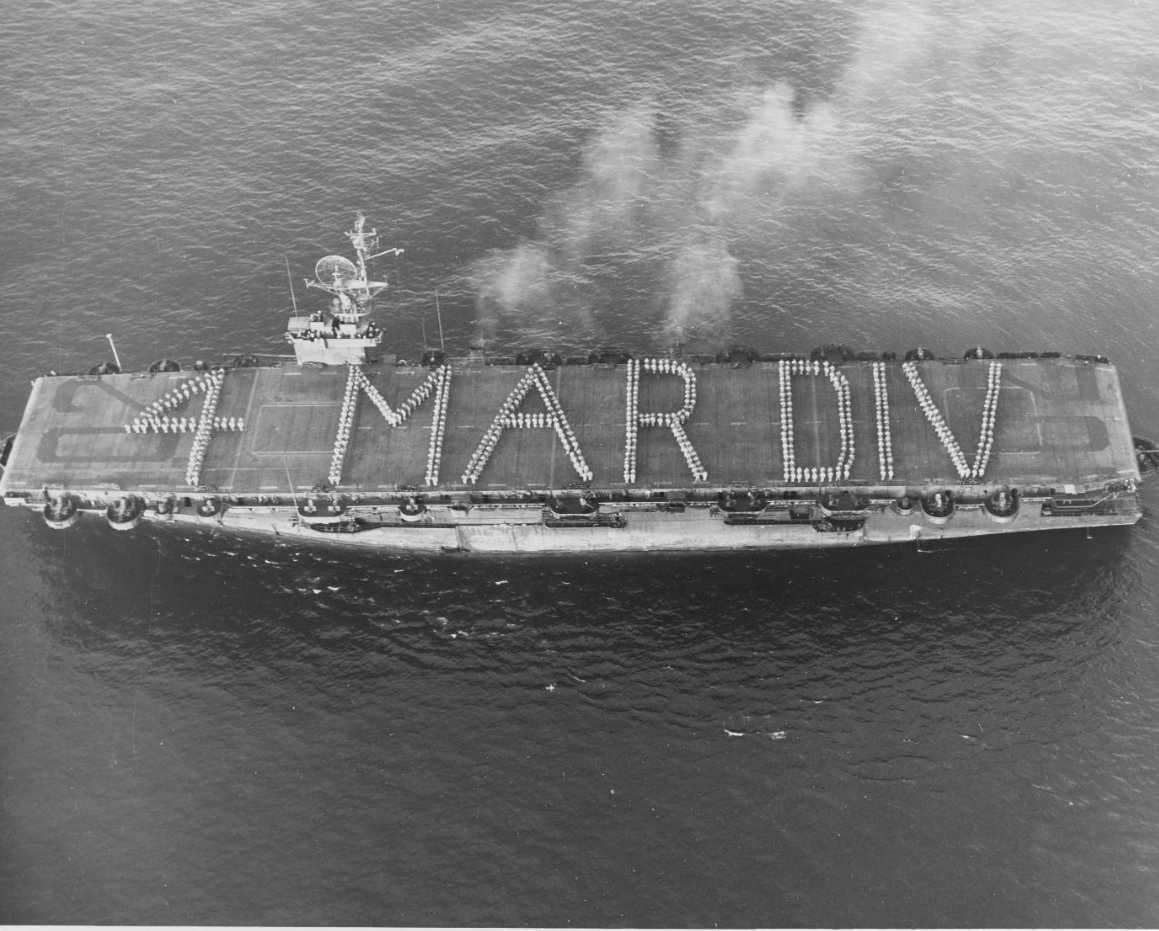

Just two days after the formal surrender ceremony in Tokyo Bay, the U.S. Pacific Fleet decided to use aircraft carriers and other ships for homeward bound troop movements. Carrier Division Twenty-Four, under the command of Admiral Henry S. Kendall, was designated Task Group 16.12 and quickly established headquarters in Pearl Harbor to direct the effort. “Magic Carpet” operations began on 10 September, which by the end of the month resulted in nearly 260,000 personnel (164,072 Sailors, 80,738 Soldiers, 8,628 Marines, and 6,418 civilians) heading homeward. Millions more would follow in their wake.[20]

To move as many people as possible quickly, the Navy modified its ships to increase their capacity. The ships would be crowded, but the Navy still aimed to make the reunion cruise a bit more pleasant than wartime passages. In addition to canteen and small stores offerings, extra equipment for athletic activities and enlarged galley spaces were introduced. The cavernous spaces of aircraft carriers facilitated the movement of large numbers of passengers, and TG 16.12 employed a total of 57 (7 CVs, 4 CVLs and 46 CVEs).[21] Providing “Magic Carpet” service right from the beginning, Saratoga (CV-3) sailed on 9 September from Pearl Harbor with 3,712 naval personnel. In all “Sister Sara” transported home 29,204 Pacific War veterans, the largest number for any ship.[22]

In addition to carriers, TG 16.12 employed hundreds of other ships in the operation. Six battleships (BBs), nine cruisers (CAs), twenty-eight attack cargo ships (AKAs), and two hundred and twenty-two attack transports (APAs) were among a total of 369 vessels. Among these was Benevolence which, following nearly three months of nursing prisoners and civilians at Yokosuka back to health, began the first of four Magic Carpet transport runs.[23] Also assisting with the massive and worldwide effort to get service members home were converted Liberty and Victory transport ships, Army transports, and the famous British luxury liner, RMS Queen Mary, which could carry 15,000 passengers. About 12,000 troops flew home from North Africa, South America, and the Caribbean. After finishing at stateside out-processing centers, most service members then had to negotiate an extremely overcrowded railway network.[24]

Aboard ships traveling home, Sailors could keep somewhat current on world events and the dynamic changes at home. James Wright and other Sailors embarked in late October aboard President Polk, for example, read in their newsletter, “The Magic Carpet,” about European leaders’ pleas for help to assist with displaced persons and devastated cities, a diminishing number of strikes in the United States, and President Truman’s desire to retain wartime powers over “rationing priorities, the draft and other wartime controls.”[25]

An overwhelming will to make it home typically held for both the ship’s company as well as the passengers. Fanshaw Bay (CVE-70), for example, had participated in many of the most intense engagements in the last year of the war, including Leyte Gulf and Okinawa and thus “debates concerning the discharge of members punctuated the conversations of ship’s company.”[26] But despite experiencing significant maintenance problems, she completed several Magic Carpet runs in the last months of 1945. As a result of Fanshaw Bay’s commitment and that of other crews during Operation Magic Carpet, over 3.1 million service members and civilians reached home from a myriad of distant locales in the Pacific and beyond.[27]

1945 America

While it may be easy to imagine the excitement and joy as millions reunited, it may be less obvious just how materially different life was from today for the service members returning in 1945. Some 140 million Americans lived in the forty-eight states, whereas approximately 331 million reside in the fifty states and District of Columbia in 2020. As the war concluded, an ebullient mood accompanied the end of gasoline and most other rationing. The wartime speed limit of 35 mph was also quickly lifted, and service members and their families looked ahead brightly to having some fun and enjoying a great flood of civilian goods. At the time, less than half of households in the country had a telephone, and over half of farms—housing some 25 million people—had no electricity. Automatic transmissions and residential air conditioning were rare, but (“snail”) mail was typically delivered twice daily.[28] However, the combination of pent up consumer demand and a great manufacturing capacity to satisfy it would, in the near future, dramatically alter the American landscape.

The war had ended and a postwar filled with great promise indeed awaited for large numbers of Americans at home. A few prescient leaders also saw peril on the horizon, but it would take just a bit longer before Cold War tensions began to assert their hold firmly on the American public and other citizenries.[29] Regardless of what came next, it was clear that World War II would leave an indelible stamp upon a great generation. Millions of Sailors and other service members; their parents, aunts, and friends at home and in factories; and leaders from across society had relied upon toughness, ingenuity, and a sense of unity to defeat tenacious foes. Like so many others, young lieutenants Elmo Zumwalt and James L. Holloway, III learned much about themselves as they were tested to the utmost.[30] Courage, energy, and optimism, the two future CNOs demonstrated, could help overcome the toughest of challenges.

—Jon S. Middaugh, Ph.D., NHHC Histories and Archives Division, July 2020

****

[1] William D. Leahy, I was There: The Personal Story of the Chief of Staff to Presidents Roosevelt and Truman Based on his Notes and Diaries Made at the Time, (London: Victor Gollancz, Ltd, 1950), 501-507. Albert Eisenstaedt’s famous photo snapped when “a white-clad girl clutched her purse and skirt as an uninhibited sailor plants his lips squarely on hers” was one of many exuberant images captured in “Victory Celebrations,” Life Magazine, 27 August 1945, 21-27. For a concise overview of a range of strategic and operational activities immediately before and after the surrender and a number of interesting aspects about the Pacific Theater, see https://www.history.navy.mil/browse-by-topic/wars-conflicts-and-operations/world-war-ii/1945/victory-in-pacific.html.

[2] James T. Patterson, Grand Expectations: The United States, 1945-1974 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996) 1-9. Following World War I, the country endured a period of intense social, political, and economic tensions. Major race riots and strikes occurred in multiple cities, along with fears of communism, inflation, and job dislocation related to the end of the war and a resulting reshuffling of jobs.

[3] Naval History and Heritage Command Archive, Washington, D.C. “Charles W. Cooper Papers,” Cooper to parents,10 August, 13 August, and 22 August 1945.

[4] Naval History and Heritage Command Archives, Washington, D.C. “James Thomas Wright Papers,” Wright to parents, 22 August 1945.

[5] Ibid., Aunt Mary to Wright, 18 August 1945.

[6] James D. Hornfischer, The Fleet at Flood Time: America at Total War in the Pacific, 1944-1945 (New York: Bantam Books, 2016), 464-485.

[7] For more on Missouri’s history, see https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/m/missouri-iii.html.

[8] Samuel E. Morsion, History of United States Naval Operations in World War II: Vol. XIV, Victory in the Pacific 1945 (Boston: Little Brown and Company, 1960), 358-370; Hornfischer, 459-466; Naval History and Heritage Command, Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships, Benevolence https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/b/benevolence-i.html and South Dakota https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/s/south-dakota-ii--bb-57--chapter-3-19451969.html

[9] Naval History and Heritage Command, “Allied Ships Present at the Surrender Ceremony, 2 September 1945,” https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/a/allied-ships-present-in-tokyo-bay.html, Morison, 362-370. The 255 ship figure includes seven civilian vessels; Morison states that 258 ships were present.

[10] https://millercenter.org/the-presidency/presidential-speeches/september-1-1945-announcing-surrender-japan

[11] Cooper to Mother, 22 September 1945; Wright to Parents, 6 October 1945.

[12] Wright to Parents, 8 September 1945.

[13] Wright to Parents, 2 October 1945; Mrs. F. T. Wright to Wright, 10 August 1945.

[14] Cooper to Mother, 28 September 1945

[15] Elmo R. Zumwalt, Jr., On Watch: A Memoir (New York: Quadrangle, 1976), 3-22; Naval History and Heritage Command, Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships, https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/r/robinson-ii.html

[16] Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, “McCain Dies Suddenly at His Home,” 7 September 1945; John McCain and Marc Salter, Faith of My Fathers: A Family Memoir (New York: Random House, 1999). 1-8. Vice Admiral McCain was posthumously promoted to admiral a few years later. His son, Admiral John S. McCain, Jr., was a submarine captain in World War II and his grandson, John S. McCain, III, likewise served as a naval officer and later served multiple terms in the United States Senate before passing way in 2018.

[17] For a detailed and poignant account of the fates of these crew members from the Twentieth Air Force who were participating in the war’s late bombing campaign, see Timothy L. Francis, “To Dispose of the Prisoners”: the Japanese Executions of American Aircrew at Fukuoka, Japan, during 1945, Pacific Historical Review, 66:4 (Nov., 1997), 469-501.

[18] Wright to Parents, 20 October 1945.

[19] William D. Leahy, I was There: The Personal Story of the Chief of Staff to Presidents Roosevelt and Truman Based on his Notes and Diaries Made at the Time, (London: Victor Gollancz, Ltd, 1950), 501-507.

[20] Naval History and Heritage Command Archives, Commander, Carrier Division 24, “Magic Carpet Operations,” 15 March 1946.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships, https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/s/saratoga-v.html

[23] Benevolence’s first run with 1,000 passengers embarked from Yokosuka on 27 November and reached San Francisco on 12 December. Her subsequent three journeys were round trips between San Francisco and Pearl Harbor. https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/b/benevolence-i.html

[24] Chester Wardlow, U.S. Army in World War II: The Transportation Corps: Movements, Training and Supply (Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, 1956), 203-204.

[25] Naval History and Heritage Command Archives, James T. Wright Papers, “The Magic Carpet: USS President Polk,” No. 5 (27 October 1945). https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/p/president-polk.html

[26] https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/f/fanshaw-bay.html

[27] Naval History and Heritage Command Archives, Commander, Carrier Division 24, “Magic Carpet Operations,” 15 March 1946. The numbers of personnel transported by Carrier Division 24 from September 1945 through March 1946 break down as follows: 1,448,868 sailors; 1,469,202 soldiers (including Army Air Forces airmen); 165,410 marines; and 39,914 civilians.

[28] Patterson, Grand Expectations, 1-8.

[29] With President Truman in the audience, Winston Churchill delivered what became known as his “Iron Curtain” speech in Fulton, Missouri on 15 March 1946.

[30] The last two CNOs to serve in combat in World War II, Admiral Zumwalt led the Navy from 1970 to 1974 before Admiral Holloway took control from 1974 to 1978.

Recommended Reading

Churchill, Winston S. Triumph and Tragedy. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1953.

Hornfischer, James D. The Fleet at Flood Tide: America at Total War in the Pacific, 1944-1945. New York: Bantam Books, 2016.

Leahy, William D. I Was There: The Personal Story of the Chief of Staff to Presidents Roosevelt and Truman Based on His Notes and Diaries Made at the Time. London: Camelot Press, 1950.

Morison, Samuel E. History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, Volume XIV: Victory in the Pacific, 1945. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1960.

Sparrow, John C., History of Personnel Demobilization in the United States Army. Washington, D.C.: Department of the Army, 1952.

Spector, Ronald H. Eagle Against the Sun: The American War with Japan. New York: Vintage Books, 1985.

United States Naval Institute Proceedings, 1945-1946.

Wardlow, Chester. U.S. Army in World War II: The Transportation Corps: Movements, Training and Supply. Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, 1956.

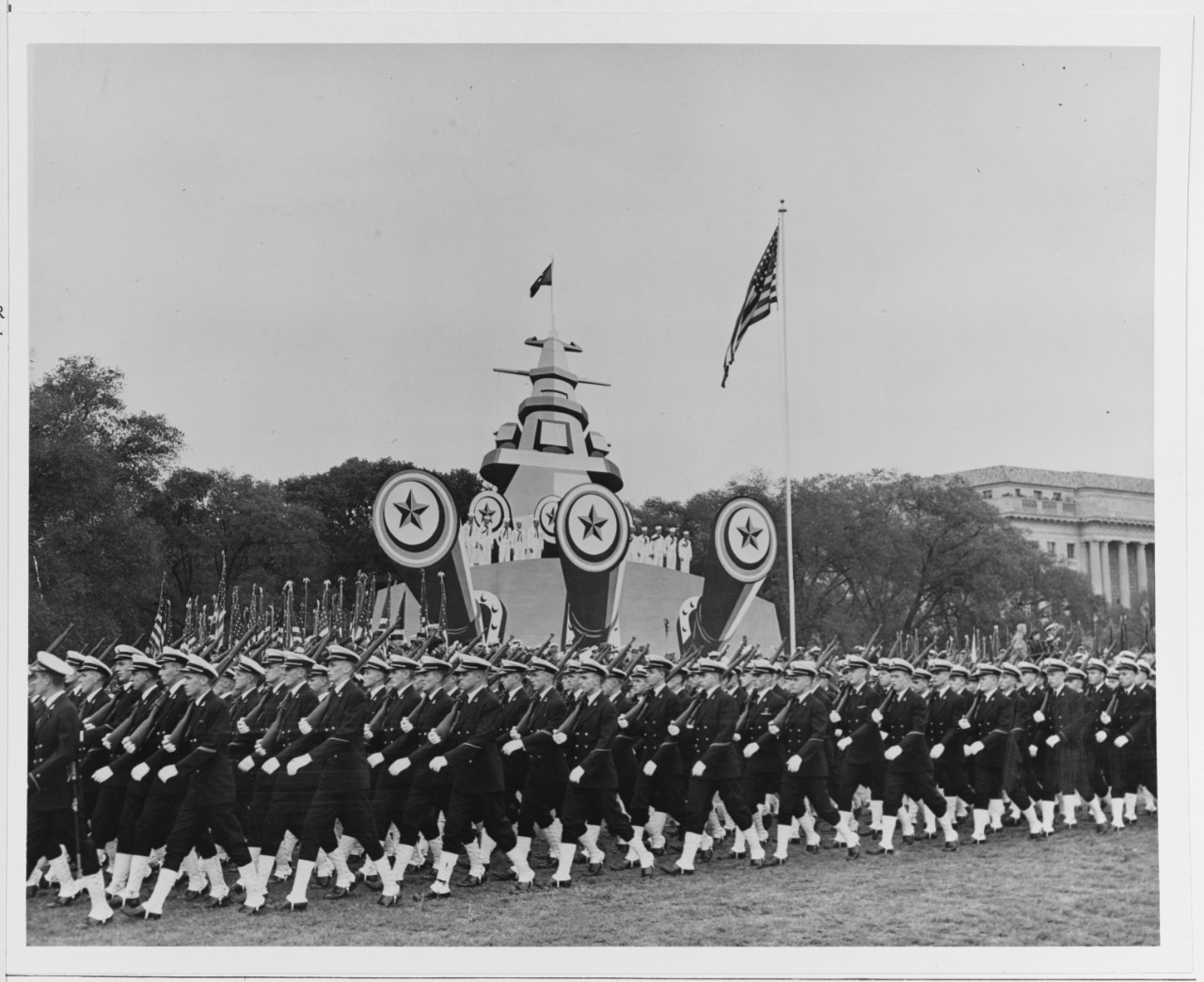

The Nation's Capital Welcomes Admiral Nimitz as the parade in his honor moves past the grandstand built to represent USS Missouri (BB-63), on which Admiral Nimitz and General MacArthur accepted the Japanese surrender on 2 September 1945. Here, U.S. Navy Midshipmen march by in review, 6 October 1945. (NH 62960)