"On the Verge of Breaking Down Completely": Combat Fatigue off Okinawa and the Destruction of USS Longshaw

Markab (AD-21) in a Pacific anchorage, with five destroyers alongside, circa 1944 or early 1945. The destroyer closest to Markab is of the round bridge Fletcher-class, otherwise unidentified. The others are, from center to right: Longshaw (DD-559); Preston (DD-795); Porterfield (DD-682); and Cassin Young (DD-793). Wartime censors have retouched the photograph to remove all radar antennas. Official U.S. Navy photograph from the collections of the Naval History and Heritage Command, NH 99281.

The strain that destroyer crews experienced during the invasion of Okinawa increased substantially after the Japanese began massed kamikaze attacks against Allied ships. With the Japanese launching four kikusui operations in the first month of operations alone, U.S. Navy picket stations were almost constantly under pressure. Sailors not only had to watch the skies for enemy air raids, but also keep alert for surface contacts and various other threats. Most “tin can” destroyer crewmembers averaged little more than four hours of sleep a day, as harassing enemy aircraft kept all hands at general quarters for hours on end. Such was the experience of Longshaw’s (DD-559) crew in the lead-up to the fateful events of 18 May 1945.

After barely escaping kamikaze attacks on two separate occasions in early April, the destroyer steamed off Okinawa through the rest of the month and into the first half of May. Conducting fire support missions during the day, she also participated in night harassing missions, and would only occasionally leave her station temporarily to steam around Kerama Retto anchorage in order to replenish her ammunition from any ship able to spare it.

Arriving at a new patrol area off Naha, at 1719 on 18 May, Longshaw abruptly ran aground on Ose Reef. With the destroyer listing eight degrees to starboard, her crew quickly implemented damage control by battening down all watertight doors. Lieutenant Commander Clarence W. Becker, Longshaw’s commanding officer, arrived on the bridge to relieve the officer of the deck (and the ship’s damage control officer), Lt. Raymond L. Bly, Jr., and take stock of the destroyer’s precarious situation.

After several attempts to free Longshaw from the reef proved fruitless, Becker welcomed assistance from fleet ocean tug Arikara (ATF-98). Lt. John Aitken, Arikara’s commanding officer, offered advice to wait until high tide in order to free Longshaw. Accepting the advice, but weary of being caught in the open, Becker ordered his exhausted crew to move 5-inch ammunition from the forward section of the ship to the main deck on the fantail while Arikara tossed over a bridle and tow line. While the fleet tug was attempting to pull the stuck destroyer off the reef, both crews watched in horror as a Japanese shell splashed between them. As the tin can’s crew immediately ran for their battle stations, the enemy shore battery firing at the stationary target struck Longshaw amidships near a 40-millimeter gun. Further shells hit the number four 5-inch upper handling room, the bridge, CIC, and the number two upper handling room, all on the port side.

Machine Accountant Third Class (MA3c) Bill N. Boston was near the port side 40-millimeter gun when Longshaw took the first salvo from the enemy battery. “The first shot went in between us and the Arikara, and the next one was right on us in the port side,” he later stated. After helping carry ammunition from belowdecks to the fantail, he abandoned ship. Attempting to avoid the oil, smoke, and flames from the burning destroyer as he treaded water, Boston “climbed back aboard…it had already quieted…and here are all these guys laying around dead.” Fearing that the Japanese would resume fire, Boston jumped off the opposite side of Longshaw, and spent two hours in the sea until whaleboats finally picked him up.

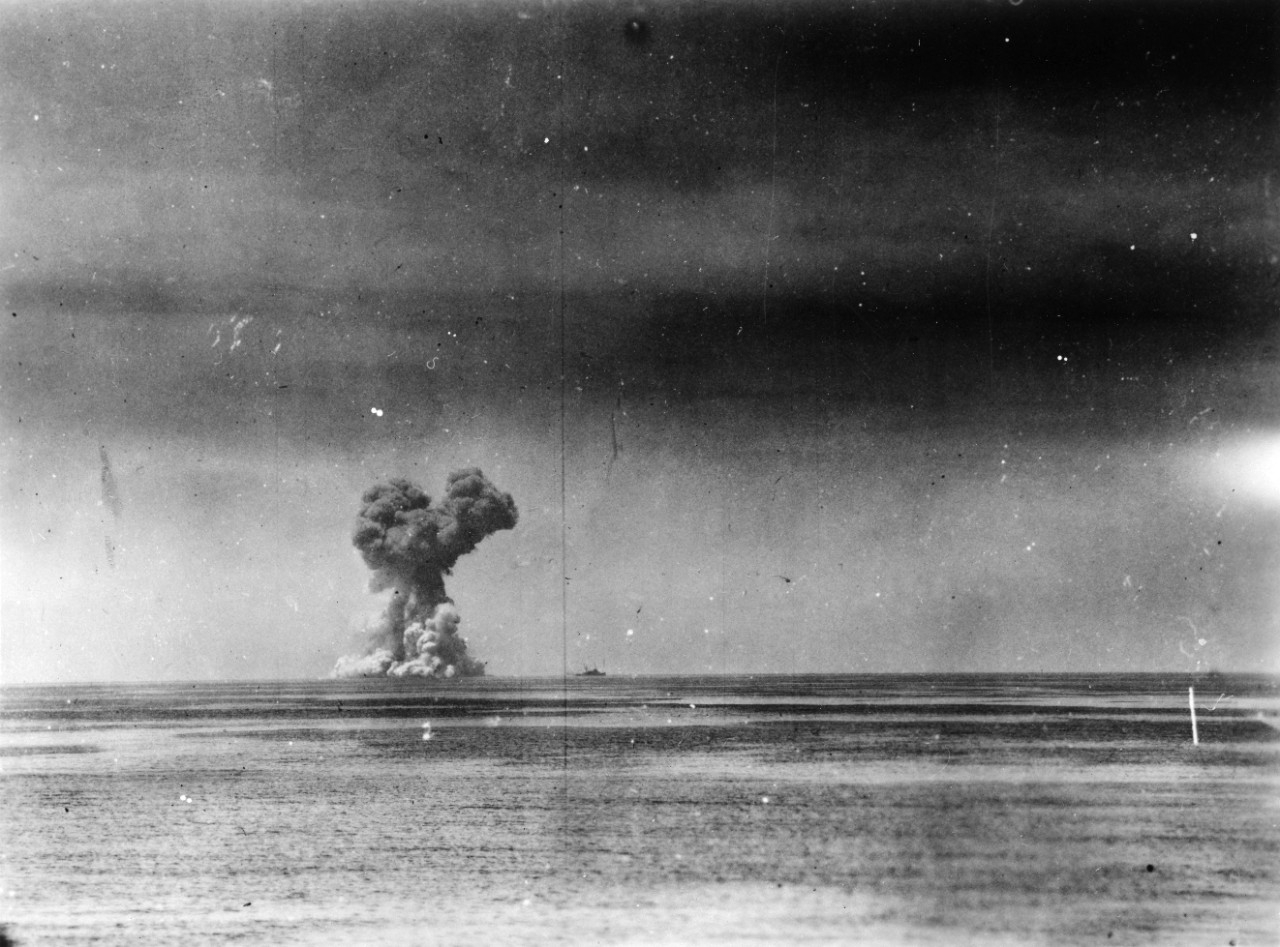

Returning fire at the enemy battery with four 5-inch rounds, Longshaw suddenly took a direct hit to her forward magazine, knocking off the forward part of the destroyer in a giant explosion. Several men died trapped belowdecks, having no way to escape the ship. Becker apparently passed word to abandon ship before succumbing to his severe injuries on the bridge. With communications knocked out and their commanding officer dead, word had to be passed by mouth to abandon ship. While several of the crew attempted to put raging fires out using only two hoses, a few others began throwing the ammunition on the fantail over the side. For several more minutes, the Japanese continued firing, wounding several more men aboard the destroyer. The firing ended as quickly as it began, and a strange silence descended over the ship save for the burning fires and cries of wounded men echoing across the water. Later that same day, after rescue ships picked up all remaining survivors, destroyer Picking (DD-685) sank the battered Longshaw by sending five torpedoes into her side.

Heavy cruiser Salt Lake City (CA-25) and large infantry landing craft LCI(L)-356 pulled 113 Longshaw survivors from the sea. The small crew of only 291 lost 86 men killed in action and another 95 wounded, for an incredibly horrific 62 percent casualty rate. Gunner’s Mate Third Class Harry W. Leonard recalled being in the water “about an hour and a half” before a small boat came in to rescue him and several other survivors. After a troopship brought the men back to San Francisco, “We were told (by the Navy) ‘don’t tell anybody your ship was sunk…don’t write letters, don’t write any letters, everything’s quiet.’” Calling his mother in Philadelphia, Leonard recounted, “The first thing she says is, “My God, are you alright?’ I said, “’What do you mean am I alright?’ She says, ‘Your ship was sunk!’”

Bly, the surviving damage control officer, believed the loss of Longshaw “can be laid indirectly to the fatigue of officers and men.” Citing long months of operating with little to no breaks in her schedule, the crew “had no recreation except the meager amount available” at Ulithi and Eniwetok, the facilities in both places so poor “that many men preferred to remain on board.” Bly stated in an attachment to Longshaw’s after action report that the psychological condition of the entire crew contributed to the destroyer’s sinking. His report stated “several times after the first 3 weeks of the campaign [that] many of the men on board were on the verge of breaking down completely with combat fatigue.”

Bly believed a fair and consistent rotation of the destroyers on station off Okinawa would have remedied crew exhaustion. He also argued that men suffering combat fatigue be relieved of duties and transferred off ship. The plan was two-fold in that it would allow the individual a respite from the war and potentially keep accidents at sea to a minimum. However, with only 291 Sailors assigned to Longshaw, Bly recognized that any system of rotating individual crewmembers off vessels while in a combat zone would be extremely difficult and unlikely. Later receiving the Silver Star for his efforts onboard Longshaw, the young officer’s recommendations while in the thick of the fighting at Okinawa went unheeded. The carnage both ashore and at sea off Okinawa continued unabated until Imperial Japan’s ultimate defeat some two months after the battle’s conclusion.

—Guy Nasuti, NHHC History and Archives Division, April 2020

Sources:

DANFS histories:

https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/a/arikara.html

https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/l/longshaw.html

Veteran Interviews:

GM3c Harry W. Leonard, Harry Walter Leonard Collection (AFC/2001/001/32406), Veterans History Project, American Folklife Center, Library of Congress.

MA3c Bill N. Boston, Bill Norris Boston Collection (AFC/2001/001/31851), Veterans History Project, American Folklife Center, Library of Congress.

War Diary:

World War II War Diaries, History of USS Longshaw (DD-559) (Fold3.com)