Admiral Spruance Recounts Kamikaze Attack on His Flagship, New Mexico (BB-40)

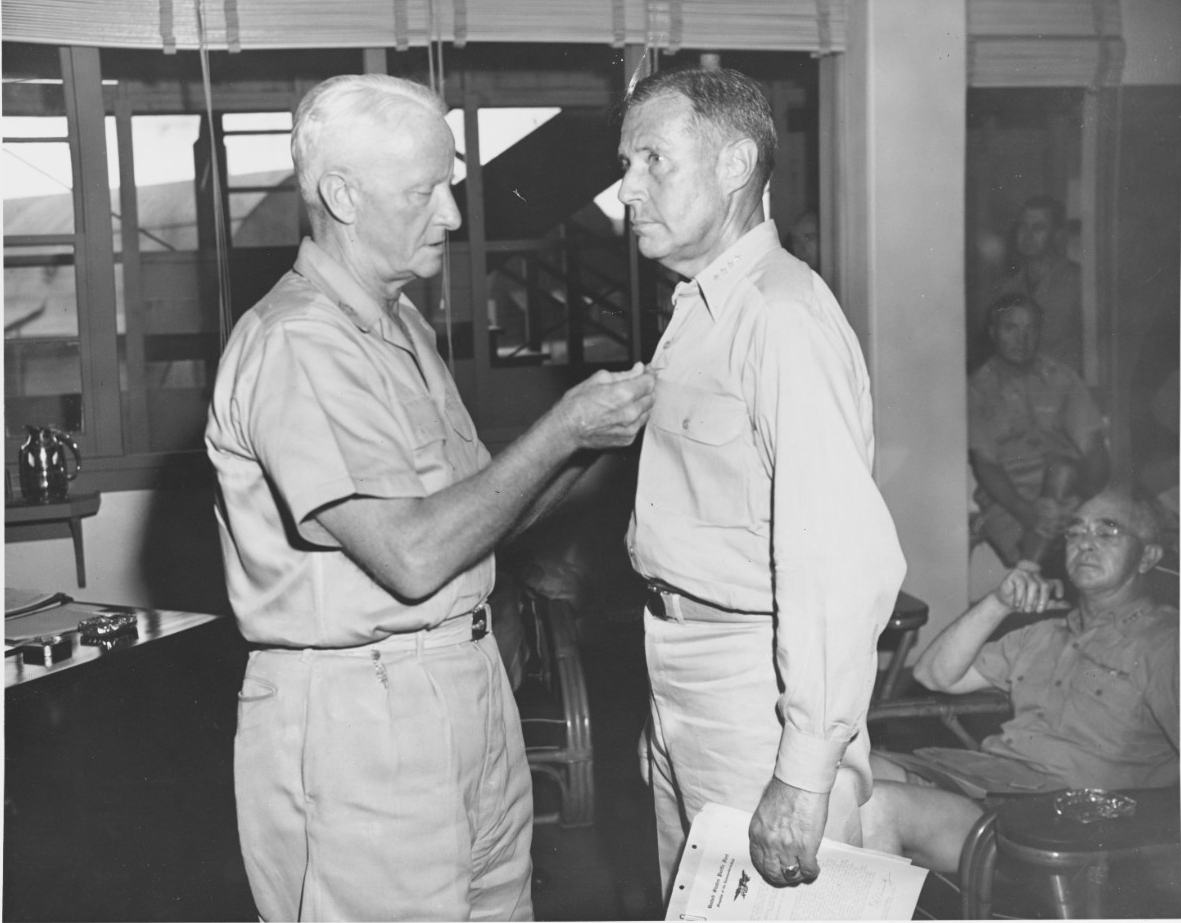

Fifth Fleet becomes Third Fleet. After nearly four months of sustained combat at Iwo Jima and Okinawa, Admiral Chester Nimitz ordered a respite for Admiral Raymond Spruance and the other commanders of 5F. Admiral William Halsey and Spruance aboard USS New Mexico at Okinawa, Ryukyu Islands, 26 May 1945, just prior to the change of command. (U.S. Navy Photo, 80-G-322429, NARA II, College Park, Md.)

On 13 May 1945, Admiral Raymond Spruance put pen to paper and described the second kamikaze attack he experienced at Okinawa. The recipient of the letter below was his longtime friend and former chief-of-staff Captain Charles “Carl” J. Moore. He wrote the day after the attack and the same day he attended funeral services for the 54 Sailors and Marines killed in the attack. Weeks later, Spruance reluctantly transferred his command to Admiral Bill Halsey, Commander Third Fleet. While the battle was not yet over, Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz decided that after three months of continuous combat from Iwo Jima to Okinawa, Spruance and staff needed a respite.

May 13, 1945

Dear Carl[1],

Thank you for your letters of April 21st and 29th. I am glad to find from the latter that your new duty will be more to your liking than you had originally thought it would be.

We have no record of the Remey[2] having been hit. Biggs[3] has been keeping a careful list of our ships that have been sunk, heavily damaged or lightly damaged during the current operation. Mostly when DDs or DEs get in one of the collisions which have been rather prevalent lately, the damage is sufficient for us to be told about it.[4] At any rate, Tim is out with TF 58 and the [Japanese][5] are still very allergic to our carriers—at least they were that way as late as two days ago. 58 is hitting Kyushu at this moment and I hope they come out intact. So far I don’t think you need worry about Tim for the next couple of weeks, for he will be having a little rest if not recreation.

Yesterday the N. Mex., which I am now riding, went over to Kerama Retto to take ammunition. We left late in the afternoon to come back to Hagushi to anchor for the night—all very quiet and peaceful all day. Just about sundown two low flying bogies came in through our radar pickets from the westward, presumably from Formosa. A few minutes before we anchored, they arrived on the scene, picked out the N. Mex. And dived on her. One was shot down, landing in the water close aboard on our port quarter. A few moments later the other landed on us, coming in on the starboard side just abaft of the foremast structure. The bomb went off on the superstructure deck just abaft the foremast, while the plane crashed into the uptake space on the forward side of the stack. The most curious part of the whole business was that ammunition from the AA battery was knocked down in the hole made by the plane and fell through the battle bars into several of the boilers where it went off, putting three of our four boilers out of commission—probably for several days. The casualties were about 50 killed, mostly in the AA batteries but some on the quarterdeck, either from strafing or from fire from other ships; about 80 men seriously wounded and a good many more with minor injuries.

Except for several of Slonim’s[6] men who were close to the bomb explosion, the flag had no casualties. Slonim had just left there to come aft to tell me the [Japanese][7] planes were close—otherwise he would have been killed. Burns[8] was knocked down on our signal bridge, but not hurt. I had just started for the bridge when the AA batteries opened up, so I remained under cover while going forward on the second deck and we were hit before I got very far, which was fortunate for me as the two routes to the bridge lead right through the area where the plane and bomb hit.

This is my second experience with a suicide plane making a hit on board my own ship, and I have seen four other ships hit near me.[9] The suicide plane is a very effective weapon, which we must not underestimate. I do not believe anyone who has not been around within its area of operations can realize its potentialities against ships. It is the opposite extreme of a lot of our Army heavy bombers who bomb safely and ineffectively from the upper atmosphere.

Okinawa is a very fine and valuable island. We have been in this area seven weeks now and there is still a lot of Southern Okinawa in the hands of the [Japanese]. The [Japanese] casualties reported by the 10th Army are pure estimates—not actual counts of dead [Japanese]. I don’t take these estimates much more seriously than I do the [Japanese] figures on our casualties. Since the push started on 19 April, we have advanced about 4,000 yards. There are times when I get impatient for some of Holland Smith’s[10] drive, but there is nothing we can do about it.

Iwo was a very tough job for the Marines, but they finished it up in 26 days. I doubt if the Army slow, methodical method of fighting really saves any lives in the long run. It merely spreads the casualties over a longer period. The longer period greatly increases the naval casualties when [Japanese] air attack on ships is a continuing factor. However, I do not believe the Army is allergic to losses of naval ships and personnel.

Out here we have been following the doings of our new President with much interest.[11] I believe the description you quoted of him is accurate. We shall not have so much strong leadership, but undoubtedly a lot more common sense, conservative, economical administrative talent shown. It may be that the country has need of that.

Forrestel’s[12] relief is ordered but about to go on 30 days leave, so it may be a couple of months before Forrestel gets away. We shall miss him greatly. Harry Hill[13] is here now with 3 stars as Com5thPhibFor and is about to take over locally from Kelly.[14] The latter part of the month I shall be relieved. Kelly and I go back to Guam to plan—for what I don’t know as yet.

Edward is now coming in from his first patrol in command, but he will probably be out again before I have an opportunity to see him.[15] He is now a proud father of about three weeks’ standing—a daughter. I don’t feel a bit older in consequence of my increased dignity. We miss you out here. The weather topside is mostly cool and pleasant, but it is generally hot enough below to make even you feel at home. Don’t take your new job too seriously, and don’t injure your colors with worry and hard work. I forgot to tell you that Johnnie Hoover[16] is back in Washington on a month’s leave. Hope you will run across him. He went up to Tokyo and Iwo with us.

Please drop me a line when you get squared away and let me know how things are going with you. My best to Anna Louise.

Sincerely,

Raymond Spruance

—transcribed and edited by Richard Hulver, Ph.D., Historian, NHHC History and Archives Division

*****

[1] Captain Charles J. Moore, Spruance’s former chief of staff. Moore was passed over for promotion to rear admiral reportedly due in part to running his cruiser, USS Philadelphia (CL 41) aground off Nova Scotia during neutrality patrols in late fall of 1941 (shortly after assuming command). Spruance persistently recommended his promotion to flag rank to Admirals King and Nimitz. Admiral Nimitz endorsed Spruance’s recommendation, however, Admiral King did not (Moore would later obtain flag rank). Moore’s rank was a non-issue until Spruance’s promotion to full Admiral, which necessitated his chief-of-staff be of flag rank. This, paired with King’s policy that either a commander of major operations, or his chief-of-staff, be an aviator, made it necessary for Moore (a captain and SWO) to be transferred. He was replaced by an aviator, Rear Admiral Arthur “Art” Davis on 1 August 1944. Davis was with Spruance for the planning of Iwo Jima and Okinawa.

[2] Remey (DD-688) did make it onto the Fifth Fleet list of damaged ships with the notation that it received minor damage from a 12 April air attack. The ship’s war diary for that period did not mention being hit around those dates, however, they do indicate that they were involved in sustained combat against kamikazes during the period and aided in shooting down multiple planes.

[3] Capt. Burton B. Biggs, Spruance’s Logistics Officer.

[4] Collisions took place frequently during underway replenishments.

[5] Spruance used a different phrasing in the original.

[6] Cmdr. Gilven M. Slonim, his Japanese Language Officer.

[7] Spruance used different phrasing in the original.

[8] Cmdr. M.C. Burns, Staff Meteorologist.

[9] Spruance’s previous flagship, USS Indianapolis fell victim to a kamikaze attack on 31 March during the pre-invasion bombardments of Okinawa. In that event, the Japanese plane clipped the ship and crashed harmlessly into the sea, but not before releasing a bomb that penetrated through the entire ship and detonated underneath. Nine crewmen were killed in the attack and the ship was forced to return to Mare Island for a refit.

[10] Lt. Gen. Holland McTyeire Smith.

[11] Harry S. Truman, who succeeded Franklin D. Roosevelt as president upon the latter’s death on 12 April 1945.

[12] Capt. Emmet P. (Savvy) Forrestel, Spruance’s Operation’s Officer.

[13] Vice Admiral Harry Wilbur Hill.

[14] Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner.

[15] Spruance’s son Edward commanded USS Lionfish (SS-298).

[16] Vice Admiral John Howard Hoover.

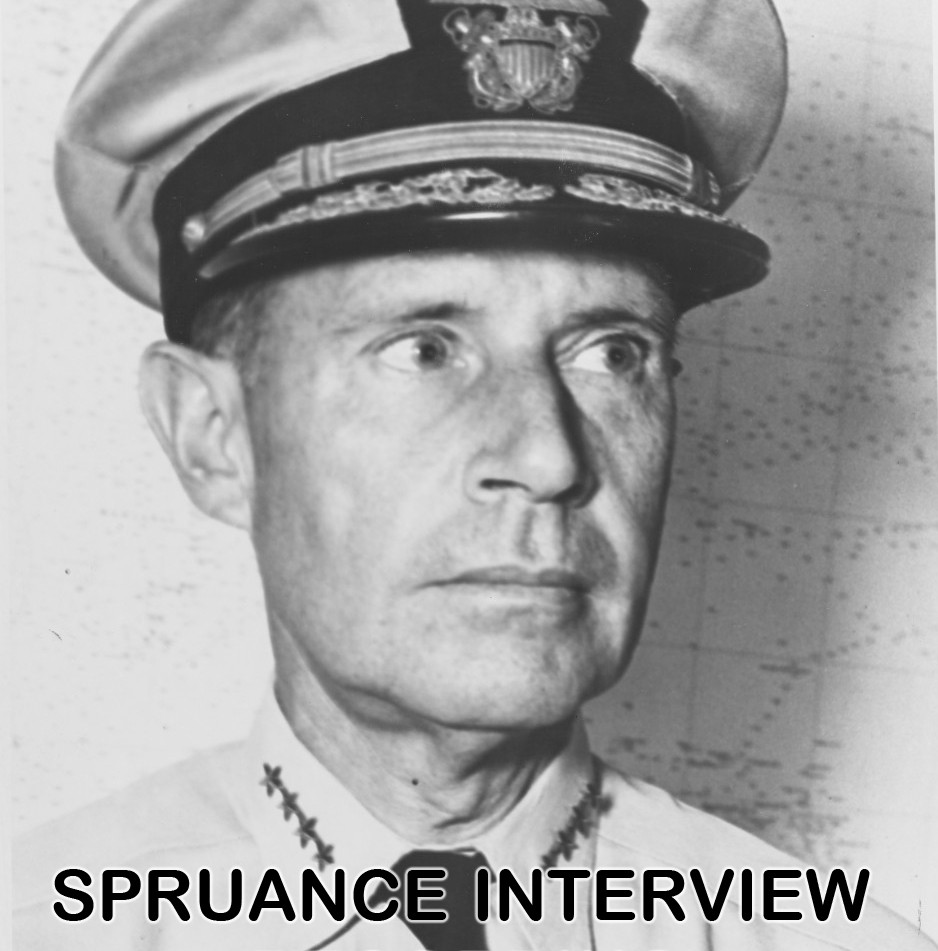

Admiral Spruance interview by Admiral Carl Moore, most likely conducted between 1960 and 1969. Though unconfirmed, the third person on the recording is thought to be Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid. The image link will lead to an audio file on the Defense Visual Information Distribution Service (DVIDS) website.

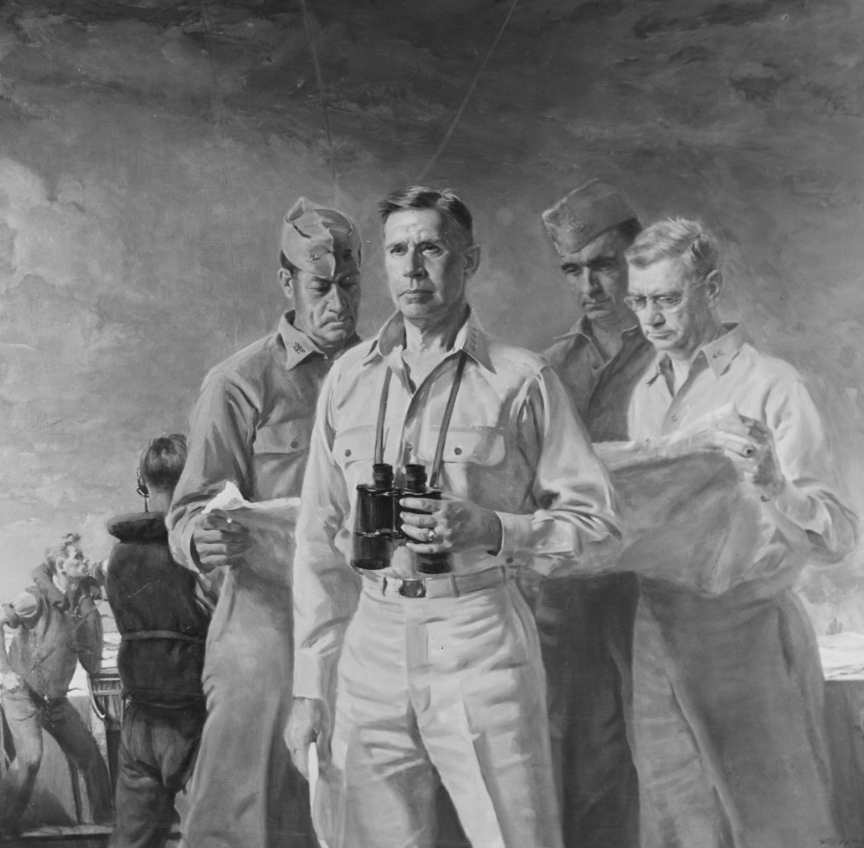

Photograph of an oil painting by Commander Albert K. Murray, USNR, Official U.S. Navy combat artist. Admiral aboard his flagship during his brilliant command of U.S. Fifth Fleet, Admiral Raymond Spruance is shown with some of his staff mentioned in this above letter (left to right), the then-Capt. Emmet P. Forrestel, Capt. B.B. Biggs, Capt. C.J. Moore, examining operational plans. Starting with the Gilbert and Marshall raids in February 1942, Spruance played a vital role in the war effort including the preparation for and command of the capture of Iwo Jima and Okinawa in 1945. (NH 124465, NHHC Art Collection).