The Battle of Iwo Jima—A Sailor’s View

On 19 February 1945, following three days of naval bombardment, approximately 30,000 American troops landed on the beaches of Iwo Jima, starting an assault on the island that continued for weeks. This assault was made possible by the Sailors who served a variety of duties throughout the invasion: navigating landing craft onto the beaches, ensuring that the Marines remained well-supplied, administering first aid to casualties, and supporting the well-being of those on the island. This photo essay showcases photographs from Naval History and Heritage Command’s Photo Archive highlighting theses Sailors’ contributions to the landings, logistical support, medical administration, and religious care at Iwo Jima.

Landings

Fleet Air Photographic Squadron Five, landing ships unloading near Mt. Suribachi, 25 February 1945. Ships seen include LSM-264, LST-724, LST-760, LST-788, and LST-808 (Naval History and Heritage Command photograph, S-139-A.02).

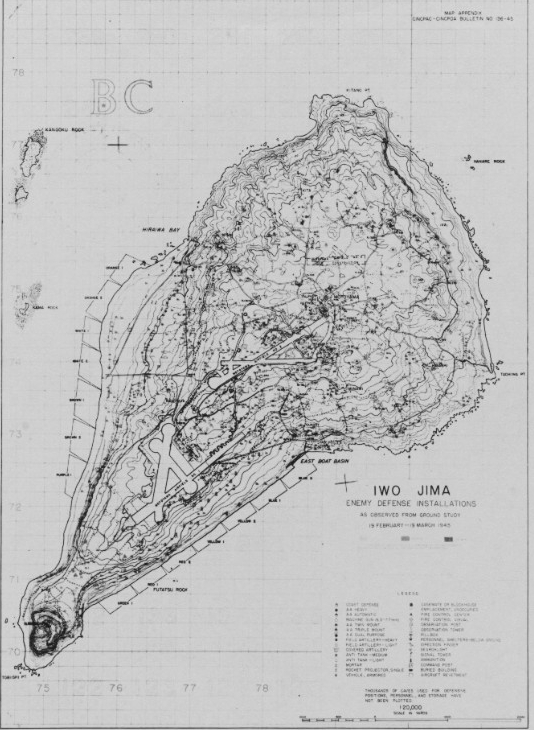

No one on the American side ever suggested that the landing on Iwo Jima would be an easy proposition, least of all Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, chosen by Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz to command the Fifth Fleet. Admiral Spruance and the other Navy planners authorized three days of naval bombardment prior to D-Day on 19 February 1945.

The weather conditions around Iwo Jima on D-Day morning were almost ideal. More than 450 ships massed off Iwo as the H-hour bombardment pounded the island. Shortly after 9 a.m., Marines of the 4th and 5th divisions hit beaches Green, Red, Yellow and Blue and initially encountered little resistance from the Japanese. Coarse volcanic sand hampered the movement of men and machines as they struggled to move up the beach. Then, as the protective naval gunfire subsided to allow for the Marine advance, the Japanese began a heavy barrage of fire against the invading force.

Landing craft on the beach at Iwo Jima – Navy and Coast Guard landing craft of all types crowd onto the assault beach at Iwo Jima to bring the 4th and 5th Marine divisions ashore (Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph, USN 48302).

Logistical Support

Sailors lower an LCM (landing craft, mechanized) from USS Rutland (APA-192) off Iwo Jima on D-Day, 19 February 1945. Rutland's landing craft operated on Red Beach 1 and 2, and the ship lost 11 of her boats during the assault (Naval History and Heritage Command photograph, NH 98947).

Sailors supported the Marines on Iwo Jima and the massive fleet offshore with a major logistical operation. On the beaches, shore personnel facilitated the arrival, unloading, and departure of landing craft, commanded by Sailors and Coast Guard personnel, full of ammunition and other supplies. Farther inland, Seabees repaired captured runways and used bulldozers to create roads, which supported the quick movement of supplies to the advancing Marines.

Offshore, ammunition, repair, transport, and various landing ships supported the campaign. Two LSTs (tank landing ships), previously converted into barracks ships, provided crews from the landing crafts with water, provisions, and fuel. Additionally, these converted LSTs offered berthing, mess, and sick bay facilities for Sailors. Sometimes, these offshore supplies flowed through less-official channels: A transport quartermaster from the 3d Division Marines departed from the beach in an LVT (landing vehicle, tracked) full of “war souvenirs” to trade with Sailors for food.

Personnel, supplies, and various LVTs remain on the beach at Iwo Jima on 25 February 1945. LST-121 and LSM-47 are beached at the shoreline, while LST-42 maneuvers behind them (Naval History and Heritage Command photograph, UA 18.02.09).

Marines camp on Yellow Beach 1 on the southeastern coast of Iwo Jima on 27 February 1945. In the distance, the U.S. Coast Guard–manned LST-761 and the U.S. Navy–manned LSM-260 are beached next to each other. Further out, an evacuation-control LST (identified by the painted letter H on her hull) remains offshore to examine and process casualties (Naval History and Heritage Command photograph, UA 18.02.22).

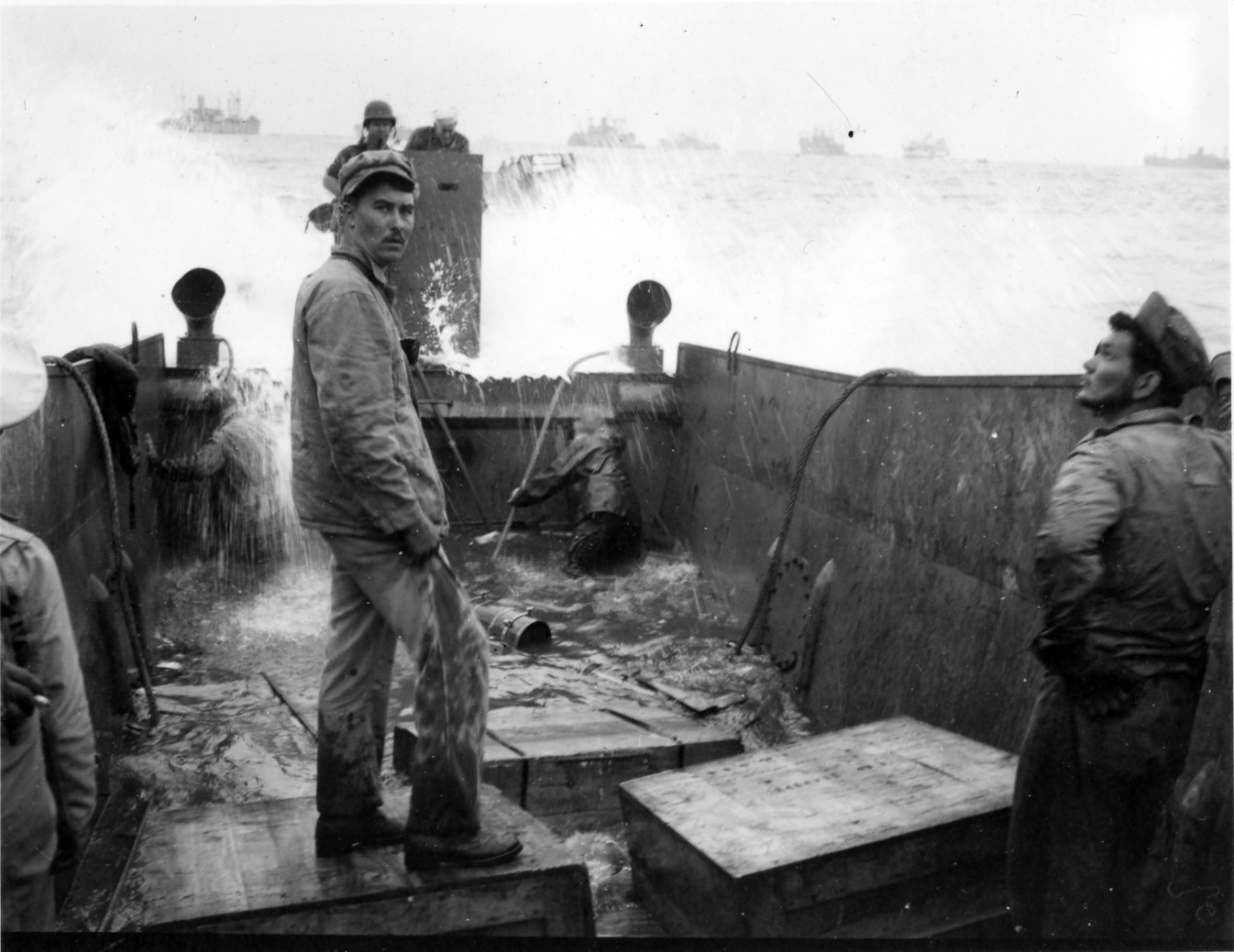

An LCM encounters difficulty near Purple Beach on the southwestern coast of Iwo Jima on 9 March 1945 (Naval History and Heritage Command photograph, UA 18.02.16).

Marines re-embark on the U.S. Navy–manned LST-247 and the U.S. Coast Guard–manned LST-764 on 14 March 1945. LST-247 had been damaged in a collision off Iwo Jima with attack cargo ship Selinur (AKA-41) twelve days earlier (Naval History and Heritage Command photograph, UA 18.02.26).

Sustaining the operations at Iwo Jima required a massive logistical effort. Captain Worrall Reed Carter, Commodore, Service Squadron 10, provided logistical support during the campaign and detailed the massive amount of supplies expended:

“4,100,000 barrels of black oil, 595,000 barrels of Diesel oil, 33,775,000 gallons of aviation gasoline, and 6,703,000 gallons of motor gas; approximately 28,000 tons of all types of ammunition; 38 tons of clothing; more than 10,000 tons of fleet freight; more than 7,000 tons of ship supplies of rope, canvas, fenders, cleaning gear, hardware; approximately 1,000 tons of candy; toilet articles; stationery; ship’s service canteen items; and approximately 14,500 tons of fresh, frozen, and dry provisions.”

Medical Administration

U.S. Navy doctors and corpsmen tend to wounded Marines at a first aid station on 20 February 1945. Navy Chaplain Lieutenant (j.g) John H. Galbreath (right center) kneels beside a man who has severe flash burns, received in an artillery battery approximately 50 yards away (Official U.S. Marine Corps photograph in the collections of the National Archives, 80-G-435702).

Navy doctors and corpsmen were instrumental to the American victory at Iwo Jima. Navy medical personnel began landing on the island on D-Day, 19 February 1945, around 9:30 a.m., only 30 minutes behind the initial landings of the 4th and 5th Marine Divisions. While Japanese shells exploded on the beaches, corpsmen administered first aid in craters and foxholes.

Medical personnel then worked quickly to set up facilities on Iwo Jima. When the men of Medical Battalion, Company A, landed near Green Beach on 28 February, they quickly set up a 110-bed hospital facility. It was finished within 8-hours of their arrival.

Pharmacist’s Mate 2nd Class Stanley E. Dabrowski, attached to the 28th Marine Regiment, landed on Green Beach shortly after the initial wave. He recalled that Japanese shelling “was so intense and the carnage and the wreckage on the beach was so fantastic.” As the Marines pushed toward their objectives, Dabrowski and the corpsmen setup a first aid station in “the deepest shell hole we could find.” Evacuating the wounded was a dangerous task and Dabrowski recalled that stretcher teams were constantly attacked by Japanese snipers. Dabrowski’s unit remained on Iwo Jima until 26 March 1945, and he finished his naval service with the occupying force in Japan later that year.

A Navy corpsman (back right) dresses a wounded Marine while others keep down amidst a terrific barrage. This photograph, likely taken on 19 February 1945, depicts the harsh conditions on the landing beaches that the Marines encountered while advancing (Naval History and Heritage Command photograph, NH 104288).

Wounded Marines take cover in a concrete Japanese shelter on Iwo Jima. Although the structure suffered a direct artillery hit, the portions still standing later saw use as an aid station (Naval History and Heritage Command photograph, L53-26.05.01).

A Navy corpsman (left) dresses a back wound on a Marine who had been hit by the enemy on Iwo Jima (Naval History and Heritage Command photograph, NH 104299).

Ensign Jane “Candy” Kendeigh ministers to serious casualties awaiting evacuation at the air strip on Iwo Jima. Kendeigh was the first U.S. Navy flight nurse to reach the island, on 6 March 1945 (Naval History and Heritage Command photograph, NH 95014).

Throughout the campaign, Navy medical personnel ran a massive operation for casualties on Iwo Jima, evacuating 7,677 casualties by 24 March 1943. This effort came at a high cost: Navy medical casualties included 827 corpsmen and 23 doctors during the campaign. Four corpsmen received the Medal of Honor for their service during Iwo Jima: Francis J. Pierce, George E. Wahlen, Jack Williams, and John H. Willis. For the latter two corpsmen, Jack Williams (FFG-24) and John Willis (DE-1027) were named in their honor.

Religious Care

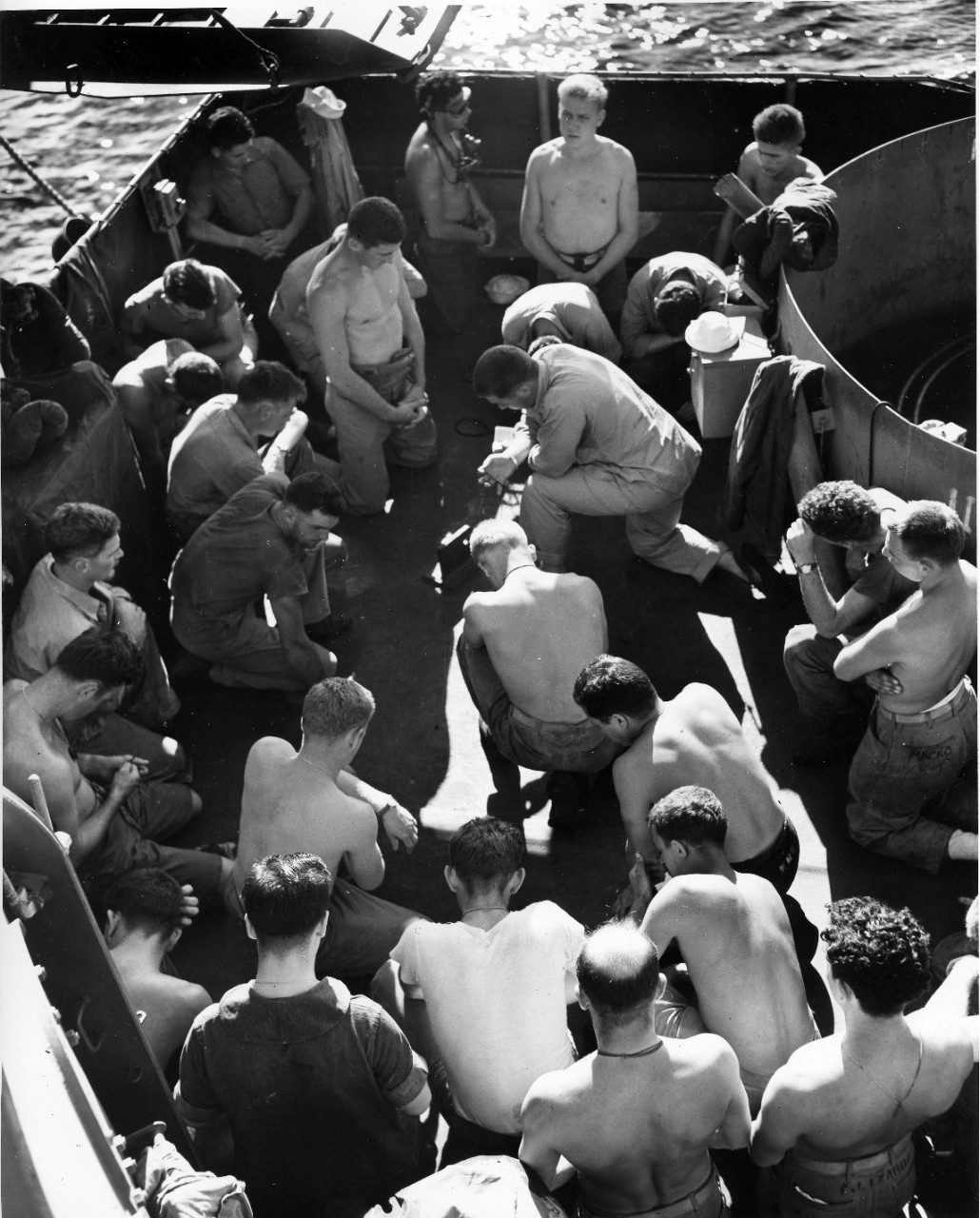

Men of the floating reserve (3rd Marine Division) attend a Catholic mass before landing on Iwo Jima on D+1 (Naval History and Heritage Command photograph, USMC 142363).

Chaplains who were part of the battle saw the death toll not as mere casualty statistics, but as a testament to the heroic and awesome men they had come to know so well. Navy chaplains went ashore with Marine units in all the major landings in 1945. Among the duties on the beaches of Iwo Jima were to provide spiritual and material comfort to the wounded and dying, hold prayer services on the beaches to cheer the spirits of the Marines still engaged in fighting, and assist with identifying and burying the dead. Chaplain E. G. Hotaling, serving with the 4th Marine Division, reported that for certain period on Iwo Jima he averaged 100 funerals a day. His annual report for 1945 listed 1,800 committal services performed on Iwo Jima. “Most jobs you can get used to,” wrote Chaplain Hotaling, “but this one is different.” “Every man you bury is a fresh tragedy, something you can’t easily forget.”

On the deck of a Coast Guard–manned LST, Marines, Seabees, and Coast Guardsmen kneel on the foredeck in final prayers before another zero hour sends them into the fury of beach battle on Iwo Jima (Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph, CG 4070).

A Catholic service at the dedication ceremony for a 4th Division cemetery (Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph, UA 18.02.21).

Sash of Lieutenant John Francis Crotty, a Navy Chaplain at Iwo Jima in 1945 (Naval History and Heritage Command artifact, 2006-9-1).

Four Navy Chaplains serving with the 4th Marine Division in the assault on Iwo Jima were awarded the Bronze Star Medal. One of them was Chaplain J. M. Dupuis. His citation read, “Landing on the afternoon of D-Day, Chaplain Dupuis undertook the administration and spiritual comfort to the seriously wounded.” He prayed over the sick, frequently under enemy fire.

Chaplain H. C. Wood’s citation noted how he “made frequent visits to front line casualty stations as well as hospitals, and was tireless in his efforts to tend to the spiritual and material comforts of the wounded.” Chaplain A. O. Martin showed similar courage in administering spiritual aid to fallen Maines on the beaches of Iwo Jima. He organized and supervised all phases of religious devotion for the assault troops of the Marine Division. “Often under fire, his inspired, consecrated, and fearless devotion to duty was instrumental in carrying the word of god to the front lines,” and providing appropriate spiritual services to the injured and dying, according to Martin’s citation.

Easter morning on Mount Suribachi: In a drizzling rain, Marines and Navy Seabees attend open-air divine services atop Mount Suribachi on Iwo Jima. Covered by a poncho, a small organ provides musical accompaniment while a small choir sings hymns. Even as Chaplain Alvo Martin conducted these Easter services, on 1 April, fellow Marines and Army troops were assaulting Okinawa, hundreds of miles away (Naval History and Heritage Command photograph, USN 49025).

Indeed, Navy Chaplains displayed immense courage in the face of tremendous odds. Oftentimes, exposing themselves to sniper as well as shellfire, Navy Chaplains reached their men, ministered to them, and comforted and cheered the wounded and dying. Chaplains visited the fire-swept beaches of Iwo Jima to help bury their fallen comrades.

Aftermath

The U.S. flag is officially raised over American Headquarters near Mount Suribachi (background) on 14 March 1945 after a proclamation from Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz officially took possession of the island (Naval History and Heritage Command photograph, NH 104584).

On 16 March 1945, Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Commander in Chief of the Pacific Fleet and Pacific Ocean Areas, released the following communiqué:

“The battle of Iwo Island has been won. The United States Marines by their individual and collective courage have conquered a base which is as necessary to us in our continuing forward movement toward final victory as it was vital to the enemy in staving off ultimate defeat. The enemy was fully aware of the crushing attacks on his homeland which would be made possible by our capture of this island only 660 nautical miles distant, so he prepared what he thought was an impregnable defense. With certain knowledge of the cost of an objective which had to be taken, the Fleet Marine Force supported the ships of the Pacific Fleet and by Army and Navy aircraft fought the battle and won. By their victory the Third, Fourth and Fifth Marine Divisions and other units of the Fifth Amphibious Corps have made an accounting to their country which only history will be able to value fully. Among the Americans who served on Iwo Island, uncommon valor was a common virtue.”

American casualties exceeded 28,600, including more than 5,900 Marines and 800 Sailors killed. As the Army moved in to clean up and the Seabees continued to build and repair airfields, Iwo Jima proved useful to the strategic bombing campaign against the Japanese Home Islands. The successful campaign at Iwo Jima was made possible by the Sailors who facilitated the landings, provided logistical support to the Marines, put themselves in harm’s way to administer medical care, and provided religious support. “Uncommon valor” truly was a “common virtue” among the Sailors at Iwo Jima.

—Lisa Crunk, D. Alexander Hays, and Mark A. Nicholas, Ph.D., NHHC Histories and Archives Division, January 2020

Further Reading

Alexander, Joseph H, Closing In: Marines in the Seizure of Iwo Jima. Washington, DC: Marine Corps Historical Society, 1994.

Bureau of Medicine and Surgery. The History of the Medical Department of the United States Navy in World War II. Washington, DC: Department of the Navy, 1953.

Carter, Worrall Reed. Beans, Bullets, and Black Oil: The Story of Fleet Logistics Afloat in the Pacific During World War II. Washington, DC: Department of the Navy, 1953.

Drury, Clifford Merrill, The History of the Chaplain Corps, United States Navy. Vol. 2: 1939–1949. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, [1949].

Herman, Jack K. Battle Station Sick Bay: Navy Medicine in World War II. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1997.

Morison, Samuel Eliot. Victory in the Pacific: 1945. Vol. XIV of History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1964.