Victory in Europe

“At the very hour of military victory in Europe, the course of events seemed to imperil all the hopes and ideals for which we had been fighting for more than three years.”[1]

--Fleet Admiral William D. Leahy

“We are now entering a world of imponderables…. It is a mistake to look too far ahead.”[2]

--Prime Minister Winston Churchill speaking before the House of Commons on 27 February 1945, and giving his report on the just-concluded Yalta Conference.

In the spring of 1945, Germany appeared on the verge of defeat, but exactly when the Nazi leaders would admit so remained unknown. As we look back seventy-five years to 8 May 1945, Victory in Europe Day, we first should highlight what the Navy did to enable the Allies’ success in the theater to that point. But then we should also recall that political and military leaders, Sailors and other service members in the theater, as well as their families back home and European civilians in desperate circumstances, lacked clarity about just what would occur next and when it might do so. Victory in Europe produced joy, relief, and a sense of accomplishment for many on the Allied side, but it also created great uncertainty for a good number of participants.

As in the Great War a quarter-century earlier, the Navy’s major strategic responsibility in the Atlantic during World War II was to ensure that men and material reached Europe (and North Africa). From early 1942 through May 1943, the “Battle of the Atlantic” had been a mixed success for the Allies. Enormous quantities of supplies helped sustain the United Kingdom and the Soviet Union, and a combined U.S.-Anglo force completed the successful amphibious assault that secured North Africa between November 1942 and the spring of 1943. But thousands of ships and millions of tons of supplies and raw materials also sat at the bottom of the ocean as German U-boats sank more shipping tonnage than American and British yards could construct it. Increasing industrial capacity, new technologies, intelligence gained through Ultra, and better training and organizational approaches combined to turn the tide.[3] Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Ernest J. King’s creation of the Tenth Fleet in May 1943 epitomized the latter. Meanwhile, air attacks on German infrastructure and the Allies’ recapture of French ports in 1944 further reduced the U-boat menace. In the first four months of 1945, Germany lost 153 submarines whereas only 85 had been sunk in all of 1942.[4]

U-boats remained a danger to merchantmen and naval ships until the very end, however. Late in the war, new “snorkel” submarine variants appeared with design advances that negated many of the techniques Allied “hunter-killer” antisubmarine groups had come to rely on. However, the Allies’ numerical advantages on land and in the skies were overwhelming by this point, and victory came before the new boats could make a difference in the European Theater. Nevertheless, the Germans “made a last determined effort… to reach the eastern coast of the United States.”[5] The Navy destroyed five of these U-boats, but on the evening of 5 May, U-853 torpedoed and sank the American collier, SS Black Point, just four miles from Block Island, Rhode Island. Down with her went twelve of the 46-man crew. The perpetrator failed to depart quickly, however, and several hours later U-853 was sunk by Atherton (DE-169) and Moberly (PF-63), which along with Amick (DE-168) had reached the attack scene some ninety minutes after the torpedoing and quickly begun prosecuting their attack.

The Navy’s tactical assistance to Allied ground forces in Europe, including famous large-scale amphibious assaults against Sicily and the Italian mainland in 1943 and then Normandy and southern France in 1944, continued in 1945 but on a smaller though still significant scale. From mid through late March, Sailors operating Navy LCVPs (Landing Craft, Vehicle and Personnel) and LCMs (Landing Craft, Mechanized) moved elements of the First, Third, and Ninth U.S. Armies across the Rhine River after nearly all its bridges had been demolished by the retreating German foe.[6] Once past the Rhine, western Allied armies moved inexorably toward the Elbe River while their Soviet counterparts ground down the Nazis in the east. On France’s Atlantic Coast, meanwhile, Vice Admiral Alan G. Kirk had operational command of a French naval task force and supporting U.S. vessels that assisted French ground forces tasked with eliminating pockets of German defenders near Royan in mid-April.[7] Vague German feelers proposed for a “tactical” surrender of forces in Italy beginning in March and along the western front in April did not materialize, but a military decision appeared eminent as May began.[8]

The human cost to get to this point had been high. Thirteen of the U.S. Army divisions fighting in the European theater had suffered an overall casualty rate of at least 100 percent. Thousands of GIs would remain unaccounted for at the time of Germany’s surrender.[9] U.S. Navy losses were substantially higher in the Pacific, but nearly 11,000 officers and enlisted lost their lives serving in the Atlantic Theater.[10]

Major questions remained about how to prioritize shipping when the guns fell silent in Europe. Should assets be used first to transport Army units and their equipment to the Pacific for the final push against Japan? How soon might ships be used to transport home the millions of service members fighting in Europe as well as their liberated prisoner-of-war brethren? What shipping must be arranged for bringing in food and critically-needed supplies to the war-torn communities of Europe? Such competing requirements made the period following V-E Day “the most complicated and in some ways most difficult phase of the war from the standpoint of troop transportation.”[11]

War Department forecasts at the time of V-E Day envisioned a steady inflow of GIs into the Pacific Theater during the second half of 1945 to force a Japanese surrender in 1946. Some 400,000 soldiers were projected to sail directly from Europe or the Mediterranean, with most of these expected to arrive by late September. Another 800,000 were to embark from the United States, many after having redeployed from Europe, to reach the Pacific by December 1945. Departing from Leghorn, Italy on 8 June, the first actual shipment of soldiers to sail directly from Europe reached Manilla on 15 July.[12]

Fortunately, only about one-third of the number anticipated had embarked for direct inter-theater redeployment when Japan capitulated earlier than expected. By 25 August, some 155,000 troops had moved directly from the Atlantic to Pacific areas, while 886,000 troops had redeployed to New York, Boston, Hampton Roads, and other stateside ports from Europe and the Mediterranean. Most of the approximate 3.5 million U.S. service members in the European Theater on V-E Day, therefore, would be able to sail for home without fighting the Japanese. This was welcome news for sure. But given the sacrifice of so many and the long periods of separation, the initial pace for demobilization must have seemed tantalizingly slow for many GIs, Sailors, and their loved ones yearning for a homecoming. Some 53,000 embarked in May, followed by 210,000 in June, mostly in Army transports and War Shipping Administration ships. By July, the flow improved and nearly 350,000 GIs began their journey home.[13] Concurrent with this movement of Soldiers, multiple Navy bases and stations throughout Europe and the Mediterranean began to shut down and smaller numbers of Sailors caught rides on the Army transports.[14]

Demobilization and redeployment plans for the months that would follow V-E Day but precede VJ Day were the products of intensive study and thoughtful consideration. However, the many compelling and competing priorities made it impossible for any proposal to please everyone. Since 1942 general goals had evolved into specific rules that prioritized “military necessity” but also attempted to be fair to service members. On 6 September 1944, the War Department released its “Demobilization Plan After Defeat of Germany,” which introduced an “Adjusted Service Rating Card” to determine who must continue serving, quite possibly against Japan, and who would be eligible for discharge. Colloquially known as the “point system,” it would allow for a partial demobilization determined by Soldiers receiving a score totaled from four factors: service credit for each month in uniform since September 1940; overseas credit; combat credit; and parenthood credit for each dependent child under 18 years old up to a limit of three children.[15] Updates adding specificity to the four factors were released on 5 May and 10 May 1945. Initial reception from the public and the service members themselves generally was favorable, but individual complaints from aggrieved GIs, their families, and politicians grew louder as the summer wore on.

Anticipating such criticism, the Army in January of 1944 began developing plans with the famous director and Army Colonel Frank Capra to make a film to explain clearly and sympathetically how demobilization and redeployment would work. In October 1944, detailed distribution release plans received personal direction from Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall, who recalled lessons from a problematic demobilization after World War I. Marshall insisted that projectors throughout far-flung bases in Europe, the Pacific, and in the United States show the film repeatedly as soon as V-E Day arrived. Indeed, most soldiers saw “Two Down and One to Go” soon after Germany’s surrender and the great majority of those polled in surveys stated that the film did either a “very good” or “fairly good” job communicating the plan.[16]

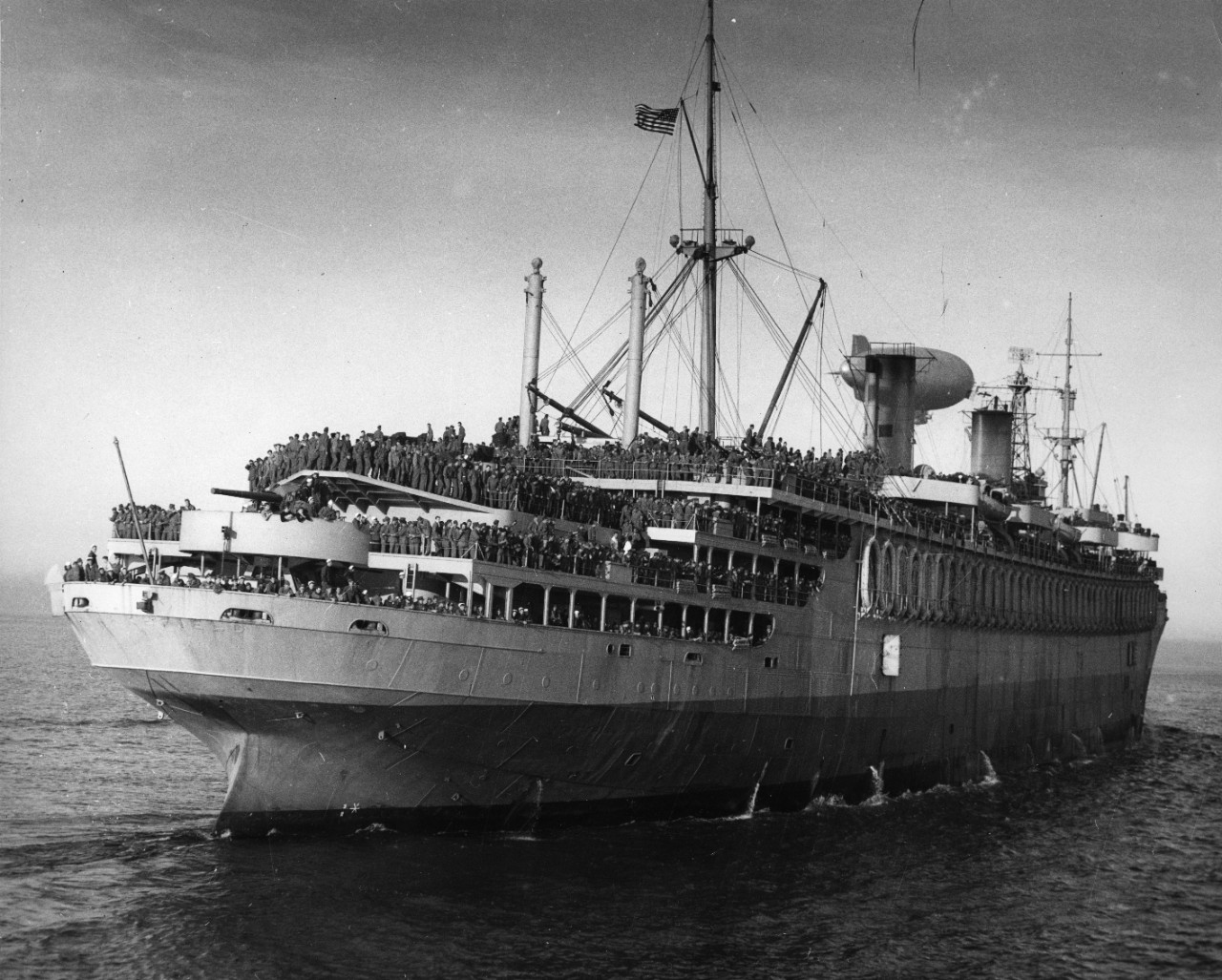

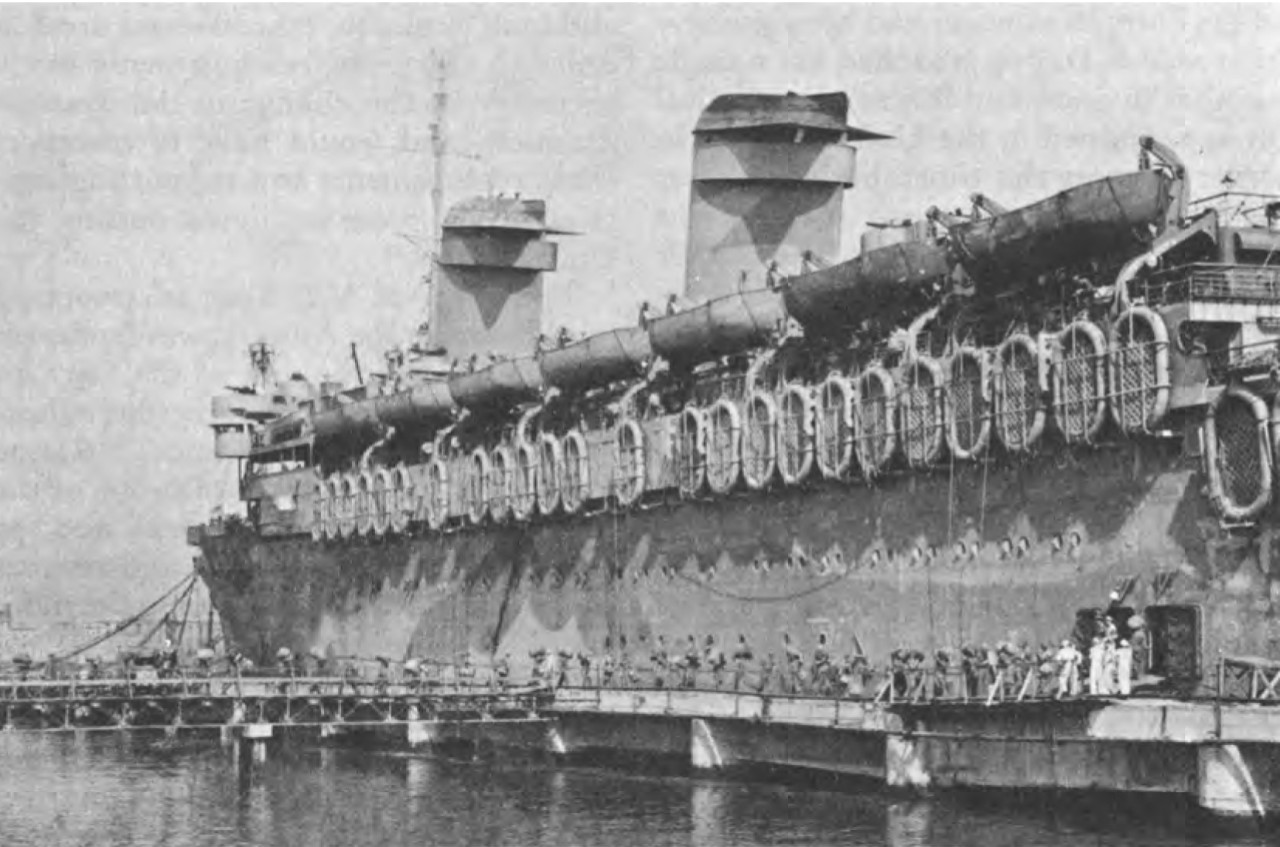

One of the Navy ships transporting soldiers home from Europe after V-E Day, West Point (AP-23), had already enjoyed a storied career taking passengers around the world. Sponsored by First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt at her 31 August 1939 launch, the cruise liner America served as the flagship of United States Lines until she was acquired by the Navy on 1 June 1941, renamed West Point, and converted to a troop transport. Up through V-E Day she traversed the world’s oceans moving service members, civilian evacuees, and others. A few days after V-E Day, West Point began embarking soldiers at Naples, Italy, for the first of many long-awaited if densely crowded homecoming voyages to the United States. When she finally left Navy service in February 1946, West Point had carried some 350,000 troops back and forth across the seas.[17]

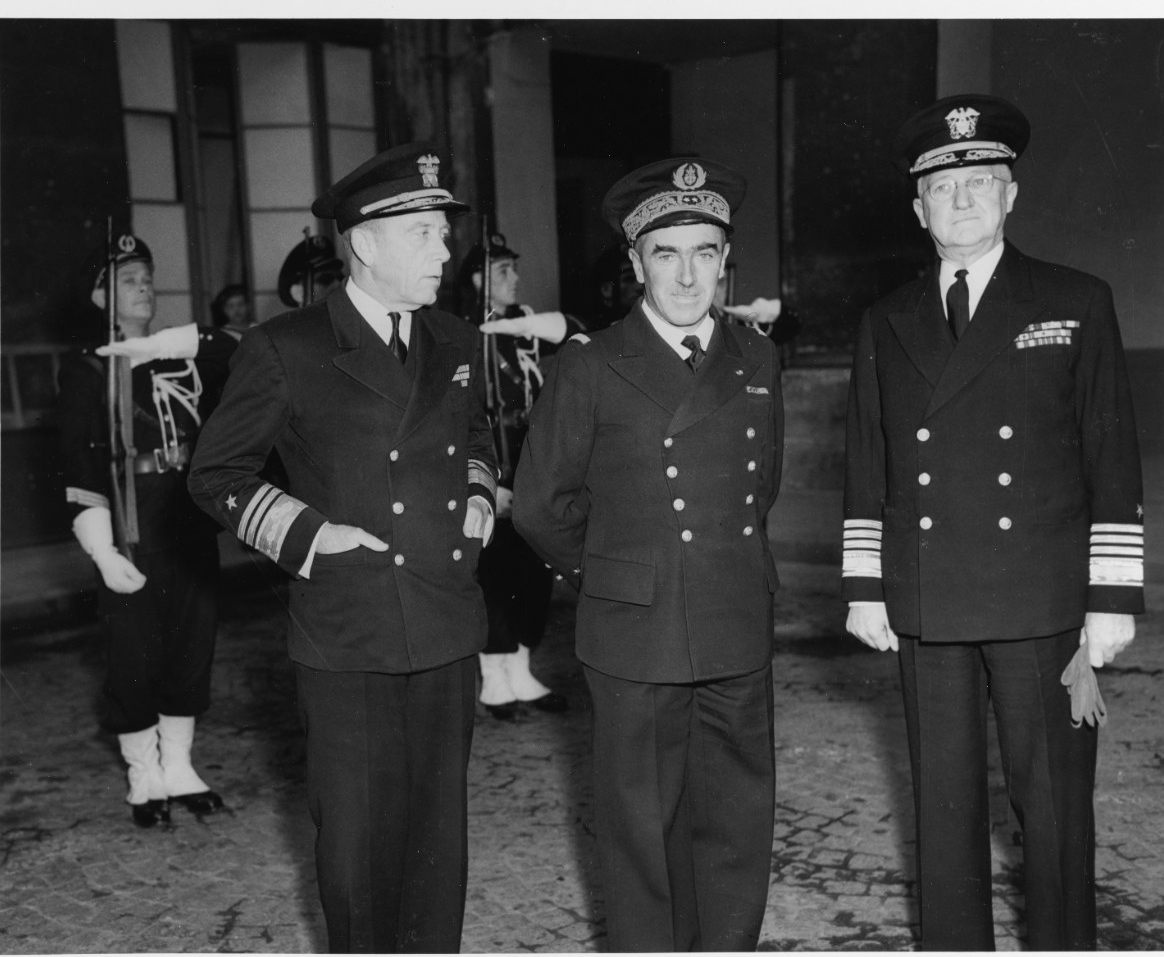

Along with these logistical concerns were major geopolitical ones. The beloved and long-serving president, Franklin D. Roosevelt, died suddenly on 12 April 1945. His replacement, Harry S. Truman, had served as vice-president for less than three months and now had much to learn in little time as American, Soviet, British, French, and other European leaders looked to shape postwar trajectories. French leaders, for example, had repeatedly inquired with Fleet Admiral William D. Leahy (who had served as the U.S. ambassador in Vichy France until 1942) to participate significantly in the recapture of their colonial possessions in southeast Asia.[18] As the spring of 1945 wound on, fates of empires and the future of the post-war world seemed to hang in the balance.[19]

When at last V-E Day arrived on 8 May, President Truman acknowledged the “solemn but glorious hour” while also reminding his constituents of the terrible cost paid thus far and of the work remaining. “Let us not forget…the sorrow and heartache of… [our] neighbors…. We must work to finish the war. Our victory is but half-won.”[20] American service members, families, factory workers, agricultural hands, and more had pulled together for some three-and-a-half years since the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941. A complete victory in World War II would eventually be achieved, but that would require yet more time. Just how much more would depend on the Sailors’, Soldiers’, and citizens’ continued demonstration of courage, determination, and cooperation.

—Jon S. Middaugh, Ph.D., NHHC Histories and Archives Division, May 2020

****

Recommended Reading

Atkinson, Rick. The Guns at Last Light: The War in Western Europe, 1944-1945. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2013.

Churchill, Winston S. Triumph and Tragedy. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1953.

Hobbs, Joseph Patrick. Dear General: Eisenhower’s Wartime Letters to Marshall. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1971.

Leahy, William D. I Was There: The Personal Story of the Chief of Staff to Presidents Roosevelt and Truman Based on His Notes and Diaries Made at the Time. London: Camelot Press, 1950.

Morison, Samuel E. The Atlantic Battle Won: May 1943 – May 1945. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1956.

Sparrow, John C., History of Personnel Demobilization in the United States Army. Washington, D.C.: Department of the Army, 1952.

United States Naval Institute Proceedings, 1945-1946.

****

[1] William D. Leahy, I Was There: The Personal Story of the Chief of Staff to Presidents Roosevelt and Truman Based on His Notes and Diaries Made at the Time (London: Camelot Press, 1950), 428.

[2] Winston Churchill, Speech to the House of Commons, 27 February 1945, as cited in Winston Churchill, Triumph and Tragedy, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1953), 399-401.

[3] For more on Ultra and the Allies’ intelligence effort to counter German submarines, see https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/u/current-doctrine-submarines-usf-25-a.html.

[4] Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King, “United States Navy at War, 1941-1945: Final Official Report to the Secretary of the Navy,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, January 1946, 156. Just over a month after VE Day, American and British officials revealed that 7,115 merchant vessels had been lost up through the German surrender. The U.S. War Shipping Administration reported that 5,579 American merchant seamen were dead or missing. U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, July, 1945, 881.

[5] King, 158; Samuel E. Morison, The Atlantic Battle Won: May 1943 – May 1945 (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1956), 356-358; Naval History and Heritage Command, Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships, “Moberly (PF-63)”https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/m/moberly.html, and Adam Lynch, “Kill and Be Killed?: The U-853 Mystery,” Naval History, Vol 22, No. 3 (June 2008).

https://www.usni.org/magazines/naval-history-magazine/2008/june/kill-and-be-killed-u-853-mystery.

[6] King, 159-160. For an overview of the Navy’s role in the Rhine River Crossings, see

https://www.history.navy.mil/browse-by-topic/wars-conflicts-and-operations/world-war-ii/1945/operation-plunder.html. For first-hand accounts from participants, see https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/r/recollections-of-lieutenant-commander-william-leide.html and https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/r/recollections-of-lieutenant-wilton-wenker-and-lieutenant-elby-concerning-the-crossing-of-the-rhine-river-in-1945.html.

[7] King, 160. For more on the elimination of German resistance near Royan, see https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/r/recollections-of-vice-admiral-kirk-concerning-the-rhine-river.html. VADM Kirk’s recollections also provide additional insights on the Rhine River crossings.

[8] Leahy, 386-391; 415-416. American and British leaders were sensitive to Soviet desires for maintaining a united front on unconditional surrender. The Soviets had been responsible for killing the great majority of German soldiers and believed that Germany hoped to receive less harsh treatment from the British and Americans.

[9] Rick Atkinson, The Guns at Last Light: The War in Western Europe, 1944-1945, (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2013), 633.

[10] Naval History and Heritage Command, “World War II U.S. Navy Personnel: Service and Casualty Statistics,”

[11] Chester Wardlow, The Transportation Corps: Movements, Training and Supply (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Army Center of Military History), 167; 231-237. “War brides” and dependent children of overseas servicemen constituted another group requiring transportation and which received much public attention. Most of the 41,502 adults and 14,712 children would be transported to the United States in 1946, with 48,408 crossing the Atlantic and 7,806 coming from the Pacific Theater.

[12] Ibid., 167-240.

[13] Robert. W. Coakley and Richard M. Leighton, Global Logistics and Strategy, 1943-1945 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Army Center of Military History, 1968), 594-619; Wardlow, 167-240, with quote appearing on 182; King, 161; John C. Sparrow, History of Personnel Demobilization in the United States Army (Washington, D.C.: Department of the Army, 1952).

[14] King, 161-162.

[15] Sparrow, 23-149, 302-316.

[16] Sparrow, 117-125. Frank Capra was perhaps the leading Hollywood director in the 1930s, with hits such as “Mr. Smith Goes to Washington.” After Pearl Harbor, he quickly joined the Army and made the “Why We Fight” series of informational-motivational films. In 1946, Capra produced the Christmas time favorite, “It’s a Wonderful Life.”

[17] Wardlow, 184; Naval History and Heritage Command, Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships, “West Point (AP-23),” https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/w/west-point-ii.html.

[18] Leahy, 335-337; 396-397.

[19] Major postwar international organizations also took shape around this time. For example, the inaugural conference determining the structure for the United Nations took place in San Francisco on 25 April 1945.

[20] Harry S. Truman, “Announcing the surrender of Germany,” 8 May 1945, https://millercenter.org/the-presidency/presidential-speeches/may-8-1945-announcing-surrender-germany. For discussion of a range of activities immediately before or after the surrender, see

Crossing the Rhine, 1945. 89th Division soldiers crouch low in their crowded assault boat, to escape enemy fire as they cross the Rhine River at Oberwesel, Germany, 26 March 1945. Note 89th Division insignia on men's shoulders, and variety of weapons (including M-1 rifles, Thompson submachine gun, and a Browning Automatic Rifle). (SC 202464)

USS West Point (AP-23) embarking troops at Naples a few days after German surrender. Photo from The Transportation Corps: Movements, Training and Supply, United States Army in WW II book series by Chester Wardlow, published by the Center of Military History, United States Army, 1990.

Crossing the Rhine, 1945. Men and vehicles of the 80th Infantry Division, Third US Army, load into a landing craft prior to crossing the Rhine River, Germany, 29 March 1945. Note M-1 Garand rifle and belt gear of man in center, including TL-29 knife, and M-1 carbines carried by other men. (SC 204858)